|

Baseball Short Story

1903 World Series, Game 3

Autumn Glory, Louis Masur (2003)

Fans who purchased the Boston Globe on Saturday morning, October 3, were treated to an editorial that praised them for their good behavior and "love of the sport for its own sake." The editors marveled at the public's devotion to baseball and proclaimed that the series "cannot but be regarded as marking the epoch of the highest development of America's national game." By late afternoon, they undoubtedly wished that they could have retracted their opinion.

Excited by the two games played so far, and stimulated by the balmy weather, not to mention the extra money in their pockets from a Friday payday, fans turned out by the thousands for the Saturday afternoon contest. By 11:00, hundreds of people stood outside waiting for the gates to open. Hour after hour, packed streetcars unloaded fans at the park. The single long lane that led to the ticket office was clogged with fans inching forward, eager to buy tickets for the third game in Boston before the series shifted to Pittsburgh for four games. The ticket sellers had no time to place the dollars and coins in the box, so they simply threw the money to the floor. Later, once the game started, there would be time to gather it.

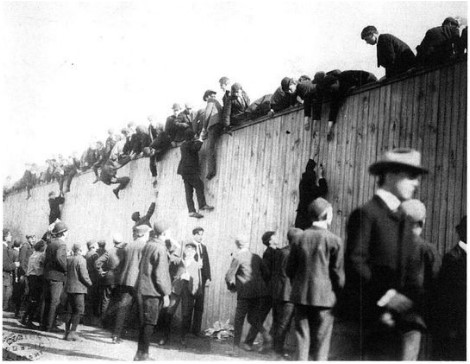

At noon, the gates opened, and a "surging, struggling mass" rushed into the park. By 1:15, all the seats had been sold and the area behind the outfield ropes continued to swell with people who jostled for position. At 2:00, fans covered the outfield, occupied the terrace, climbed the fences, even found their way to the roof. Ticket speculators made a fortune, offering general admission bleacher tickets for $1–$2 and reserved grandstand seats for as high as $10. Even the peanut vendors and scorecard boys made out by selling buckets and boxes for people to stand on for $1 apiece. The ticket office closed, and the speculators ran out of seats. Yet people were still arriving. Some 3,000 fans clustered outside the Huntington Avenue Grounds and clamored for admission. Once the game started, those in the bleachers called out to those in the street, reporting what was happening on the field.

Fans gaining "fence admission" to the third game of the 1903 World Series.

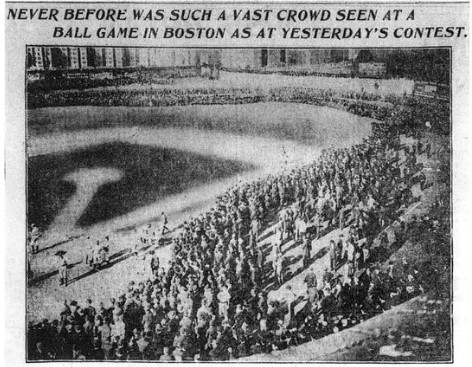

The official attendance was put at 18,801, but that figure was low. Probably between 20,000 and 25,000 people jammed themselves into the park. The situation seemed unstable. Anticipating a larger Saturday crowd, Boston's business manager had arranged for 50 policemen, up from the 35 at the previous game. But as many as 150 officers would have had trouble containing this gathering. As the crowd swelled, it vibrated back and forth in waves. Fans stood ten deep in the outfield. Suddenly, at a little after 2:00, a few men slid past the ropes in center field. Others started to press toward the field from the third-base bleachers. Within seconds, a stampede began. Thousands broke through the ropes and covered the entire field. They "tore across the diamond … drove the two teams from their benches, swept restlessly around and around the entire lot, and they determined to get as close to the play as possible." "A surging, struggling, frantic crowd," reported the Boston Post, "a sea of faces, a perspiring mass of humanity that fringed the fences, packed and jammed the stands, encircled the diamond and fought both police and players."

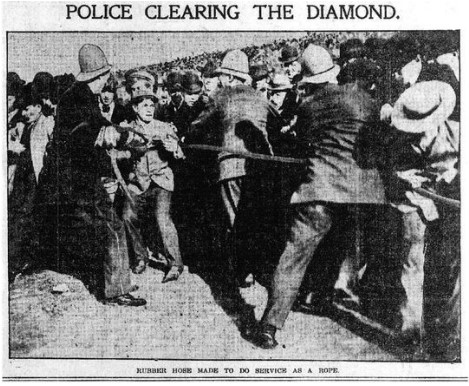

Fans on the field before the third game of the 1903 World Series

The scene was unfathomable. In their desire to get closer to the action, the exuberant fans, described as "good natured," threatened the game, the players, and their own physical welfare. The police, aided by several players, struggled to prevent the mob from invading the reserved grandstand section. Two women, caught in the crush, were rescued by Chick Stahl (Red Sox outfielder) and several policemen. The fans packed the field, and the police began trying to move them from the infield. Time and again the police would charge, with their clubs drawn, only to discover that the crowd would rush back to fill each area shortly after it was cleared. Boston's business manager raced into the dressing room and returned with an armful of bats for the police, who used them against the shins and skulls of unruly fans. The victims grabbed themselves as if poked with a "white, hot brand." Some fans saw "stars which no astronomer has yet mapped."

The police could not restore order and clear the diamond. The game would have to be postponed, or worse, forfeited to the Pirates. At 2:45, a hundred additional officers rushed to the grounds, although the mounted unit the police had requested never arrived. One policeman, who weighed nearly three hundred pounds, had a "unique method of pushing back the crowd." He would "throw his arms in the air and then run like a mad bull into the midst of the encroachers. His efforts had great effect." A patrolman brought out a long length of rubber hose and, with four men on each side, the police used it as a battering ram to force the crowd back. With a concerted push, they cleared the diamond. Then they moved to the outfield where "inch by inch the swaying mass fell back … . Forty feet was gained in 20 minutes." At the same time, "the members of both nines, anxious to get together in the decisive battle of the local series, were using their bats in much the same manner as the police did the hose."

The best the police could do was to move the crowd about fifty yards behind the diamond. Along the baselines on first and third, the crowd was packed to within fifteen feet of the playing field. Behind the catcher, a space of about thirty feet was cleared, and men lined up ten deep in front of the backstop. The players were closed off from their benches and sat on the grass to the side of the catcher. The fans who crowded in front of the stands would be dangerously close to the action, but the patrolmen decided to leave them there, "knowing that a few foul balls would clear this part of the field better than the most strenuous suasion."

The Pirates came out to warm up. Second base was missing. Fred Clarke threw his cap down as a substitute, much to the amusement of the crowd. Finally, a "230 pound policeman gained fame by rescuing [the bag which] had been stolen by a 57-pound newsboy." After a few hit balls, the fans again drifted onto the field. The bell rang for Boston's turn, and the Pirates finished their warm-up having handled fewer than twenty chances. Screaming and waving his arms, Jimmy Collins (Red Sox player-manager) urged the crowd to give the home team more room. A little after 3:00 p.m., Collins, Clarke, and umpire Connolly met to discuss ground rules. Connolly once remarked that "the constant woes of an umpire's life are the height of a pitch, rain, and darkness." He neglected to mention the fans. The group decided that balls hit into the outfield crowd, which stood only about 150 feet beyond the base paths, would count for doubles.

Remarkably, the game began only fifteen minutes late. Boston sent the young righty "Long" Tom Hughes to the mound. The six-foot-one Hughes was coming off his best year, in which he had won 20 games and lost only 7. Hughes hailed from Chicago and broke in with the National League Cubs in 1900, but he signed with the American League in 1902. He was a control pitcher who used a change of pace to fool the hitters.

|