|

Russell Ford's New Pitch

Tales from the Deadball Era, by Mark S. Halfon (2014)

The offense got its first break when a cork-centered "lively" baseball replaced the old "dead" one. League officials secretly experimented with the new ball at the end of the 1910 season but officially introduced it in 1911 with immediate results. In the American League alone batting averages jumped thirty points (the largest leap in a single season), and .300 hitters tripled. And then there were the .400 hitters. Rookie Shoeless Joe Jackson batted .408, although it was not good enough to win the batting title. Cobb hit .420 and followed that with a .409 average in 1912. Baseball's hitting frenzy, though, did not last; pitchers had something up their sleeves.

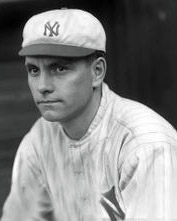

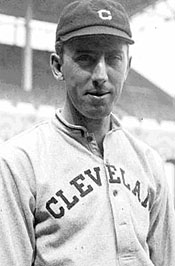

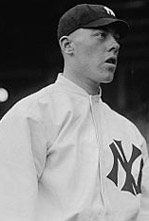

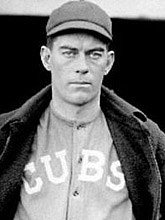

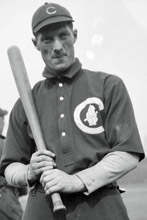

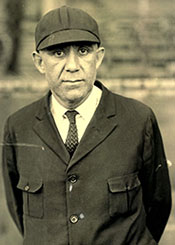

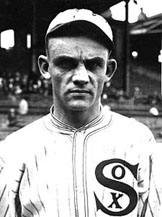

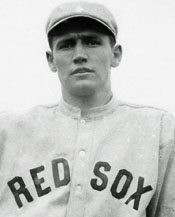

A previously undetected freak delivery surfaced that helped end the latest batting surge, although serendipity rather than a response to the lively ball led to its discovery. As right-hander Russell Ford warmed up for a minor league game in 1907, he lost control of a pitch that bruised the baseball when it struck the grandstand. His next delivery dropped so sharply that it stunned catcher Ed Sweeney. Ford threw one more pitch, and again the ball broke erratically. The young hurler stumbled upon what would become a devastating weapon, but he chose not to use it at the time and wisely kept it a secret. Ford broke into the Major Leagues with the Highlanders in 1909 and pitched one game before New York demoted him to its Jersey City Minor League club, where the now twenty-six-year-old decided to take advantage of his earlier discovery. "I made a scientific study of the ball and its freak moves, and as I was the only pitcher who even knew that it existed, I had the field to myself, he said." Ford attached a piece of emery paper to his now "loaded" glove and smoothed a small surface of the baseball, which caused it to move in ways that made the spitball look tame by comparison. Whereas the spitter had one downward break, what became the "emery ball" had four breaks—in, out, up (as much as a foot), and down (as much as two feet). The formerly unimpressive hurler gradually gained control of the pitch, making it break in whatever direction he wanted, depending on the location of the scuff and position of the grip. It earned him a trip back to the Majors. Ford put on a show in 1910 in one of baseball's most remarkable rookie seasons. He won his first eight games, including four shutouts, and appeared unhittable. Ford "has developed into the best pitcher in the big leagues," the Atlanta Constitution wrote. Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, and Three Finger Brown pitched that season. Ford's performance stunned observers, but only Sweeney and a handful of trusted teammates knew the secret to his success. Everyone else thought that he had developed a new variety of the spitball, which one writer described as the "freakiest of all freak deliveries." Ford finished the year at 26-6 with eight shutouts. Worried that others might learn about the pitch, Ford took special precautions to avoid detection. Instead of sewing a piece of emery paper into his glove as he had done before, he made a leather ring with a small rubber disc to which he attached a piece of emery paper. Ford put the ring on his middle finger and slipped it into his glove until it came opposite a hole in the glove (a common affliction of the day). Ford also continued to place his fingers to his mouth to give the impression that he was throwing the spitball, which he rarely used anymore. Despite his best efforts, though, another pitcher soon learned the secret to his success. Right-hander Cy Falkenberg went an unimpressive 76-83 for three teams in nine seasons and found himself languishing in the Minors in 1911, but good fortune smiled on the struggling "slow ball" pitcher when second baseman Earle Gardner, one of Ford's former teammates, informed him about how a piece of sandpaper could transform his career. Falkenberg listened intently, and after gaining control of the new pitch, he mowed down opponents and received a call back to the Majors in 1913. Astonishingly, he won his first ten games. Senators manager Griffith and White Sox coach William "Kid" Gleason suspected that Falkenberg had tampered with the baseball and examined it when he pitched but did not notice the almost invisible smoothed spot. Falkenberg won twenty-three games that year, second best in the league behind Walter Johnson.    L-R: Russell Ford, Cy Falkenberg, Ray Keating Collins stood motionless. He never took his bat from his shoulder. He studied Keating's actions carefully and when Umpire Connolly declared him out on strikes for the second time, Collins insisted that the arbitrator make an examination of the ball. The umpire did so and discovered a large rough spot on the leather sphere, which Collins insisted made it possible for Keating to get the unusual break on the ball. He also requested that Connolly examine the glove used by Keating, as he insisted he was creating the rough spot by means of a substance concealed in the glove. Connolly did so and, much to his surprise, discovered a piece of emery paper concealed therein. . . . That was the public birth of the emery ball, wrote umpire and syndicated columnist Billy Evans.One day after the Keating incident, umpire Charles Rigler caught Cubs right-hander Jimmy Lavender throwing the illegal pitch. Lavender cleverly, he thought, attached a piece of sandpaper to the inside of his uniform and after turning to center field reached down his pants whenever he wanted to scuff the baseball. Phillies manager Red Dooin grew suspicious and asked Rigler to search Lavender. As the umpire approached the mound, Lavender ran toward right field and handed the sandpaper to second baseman Heinie Zimmerman, but Phillies third baseman Hans Lobert had been in close pursuit and retrieved the incriminating evidence. Rigler kept the baseball to turn over to authorities but allowed Lavender to stay in the game. Without his cheat sheet, he surrendered eight runs, including three homers (two by Gavvy Cravath) over the next four innings. Shortly thereafter, the three Major Leagues outlawed the emery ball.    L-R: Eddie Collins, Jimmy Lavender, Heinie Zimmerman Was the '19 Series the First Rigged One? The Original Curse: Did the Cubs Throw the 1918 World Series to Babe Ruth's Red Sox and Incite the Black Sox Scandal, Sean Deveney (2010)

There's virtually no chance that the Black Sox were the first team to play a crooked World Series. In the SI article, [Chick] Gandil discusses the World Series proposal Boston gambler Sport Sullivan made to him in 1919. "I said to Sullivan it wouldn't work," Gandil said. "He answered, 'Don't be silly. It's been pulled before and it can be again.'" But other than 1919, there's little hard evidence of fixed championship games. There is, however, a long list of World Series whose honesty remains dubious:

Wild Days in New Orleans

Standing the Gaff: The Life and Hard Times of a Minor League Umpire,

by "Steamboat" Johnson (1935) A Southern Association umpire recalls bizarre incidents in games in the Crescent City.

New Orleans in the days of Jules Heinemann when baseball was at its height was a tough spot for umpires, and I have had my share of jams there. One of the run-ins that I remember most clearly was when Bert Niehoff had the Mobile club going for a pennant. Let me say right here that Niehoff is a smart capable manager, and as long as an umpire was hustling and keeping right on top of the play he would never give any trouble. Let an umpire give Bert the idea that he was asleep at the switch, or loafing on the job, and Bert could cause more trouble in five minutes than some of them could in a whole season. Along in the middle of the game - it was a hot July afternoon - Bert came up to me and said - speaking of the New Orleans pitcher - "Steamboat, that fellow Craft is using something on the ball. Watch him."

Next inning I saw Craft going back to his hip pocket with his right hand, so I called time and ran out to the pitcher's box. Craft was standing there looking at me with his hands down at his side to see what I was going to do. I went behind him, reached into his pocket and brought out a long piece of licorice, such as small boys chew.

I said to Craft: "You're out of the game," and turned and started for the plate. Just as I got to the plate, Craft had come up behind me. He grabbed me around the neck, and he was not trying to pet me, either. I was so surprised I could do nothing for a minute, but I finally managed to jerk loose. I maneuvered until I was backed up against the backstop and was swinging my mask at his head, as he kept coming in and mixing it with me. By this time, four or five players crowded around and stopped the fight. Larry Gilbert put in another pitcher, and the game was finished. A crowd milled around the dressing room after the game, but I was not harmed. They all thought Craft had tobacco in his pocket and was just reaching for a chew; but I knew better and, besides, had the licorice. I sent it into President Martin with my report.   Jules Heinemann and the stadium that was named for him Along in the middle of the game, Ray Gardner, New Orleans shortstop, was at bat. Hollis McLaughlin, the Birmingham pitcher, threw one so close to Gardner's head that Gardner took it for a bean ball. In a flash Gardner lost his temper and sailed out after McLaughlin. Pel Ballenger, the Birmingham third baseman, rushed over to help Mac. They began to mix it up on the mound, and Joe Sonnenberg, a police captain who was at the game in civilian clothes, came out of the grandstand on the run to stop the fight. Max Rosenfeld, Birmingham second baseman, thought Sonnenberg was a fan and met him with a solid lick to the jaw. It was a fast, furious battle while it lasted, but the bluecoats stopped it and took Rosenfeld off to jail. Umpires Brennan and Shannon and I, who were handling the game, told President Heinemann that we would not allow the game to be resumed until he got Rosenfeld out of jail, since the player had hit the police captain through a mistake. It took two hours to get Rosenfeld back from jail, and then we resumed play where we had left off. The final score was 25 to 16 in favor of New Orleans. Fifteen two-base hits were made in all. The elapsed time from start to finish was 4 hours and 10 minutes.  Red Torkelson

Late in the 1925 race Atlanta was playing in New Orleans. The game was close, and "Red" Torkelson, usually an easy-going sort of player, was at bat. A good strike came over and I called it.

On my way to the dressing room I got a pop-bottle shower. The police rallied around and took the bottle shower, too, just to see that I got safely off the field. The crowd waited for me outside the park, so Superintendent of Police Mooney, since deceased, took me down to the police station in his car and several hours later took me to the Hotel Monteleone where the umpires were stopping.Red turned around and said: "Steamboat, that ball was not over the plate." "It was," I said. Red stepped out of the box and began calling me everything he could think of, and Red had an active mind. "Out you go, Red," I said. "You can't put me out," he said. "But you already have been out for a long time," I said, and so out he walked. Then Buddy Rezza came to bat, and he took up where Red left off, looking back and talking to me. I told him: "It will cost you less to look at the pitcher than at me." Well, Buddy stepped out of the box and talked himself out of the game. That made two in all, and I knew I was in for it. Heated Rivalry 1921: The Yankees, the Giants, & the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York,

Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg (2010) New York versus Brooklyn was baseball's most heated rivalry, one that did not need modern-day hype to express it. Long before shows of "hatred" for the other team were a way for fans to get their faces on television, the fans of each of these two clubs truly detested the fans and players of the other and were quite willing to show their feelings. While relative position in the league standings was mostly irrelevant when the two teams played, the fact that they were two of the leading contenders for the [1921] pennant, as they had been the year before, only heightened the sense of drama. On two occasions in 1920, once at Ebbets Field and once at the Polo Grounds, police had to be called to end fights that had broken out in the stands.

The antagonism between the fans of the two National league clubs dated from well before the 1898 incorporation of the then independent city of Brooklyn into Greater New York. Losing their independent status likely inflamed the sense of inferiority many Brooklynites harbored when comparing their city-turned-borough, large parts of which were still farmland, to Manhattan, the "sophisticated" colossus across the East River. Similarly, those living in Manhattan had little or no interest in what went on in Brooklyn. Joe Vila, writing after the Dodgers' loss to Cleveland in the 1920 World Series, said this: "Dyed-in-the-wool New Yorkers didn't enthuse over the World's Series because the Giants and Yankees were not the participants. They were lukewarm in their sentiment for the Brooklyns for the reason that nothing on Long Island except the race tracks ever interests residents of Manhattan and the Bronx."

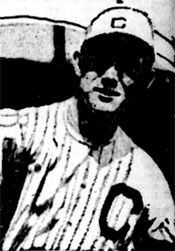

L-R: Bill Dahlen, John McGraw, Wilbert Robinson Adding fuel to the fire was the enmity between John McGraw and Wilbert Robinson, the two managers. Robinson had been yet another of McGraw's teammates on the great Orioles teams of the 1890s. Despite the difference in their ages - Robinson was ten years older than McGraw - the two men developed a close friendship and later became business partners in a Baltimore billiards parlor. In 1911 McGraw added Robinson to his coaching staff, where he remained through 1913. Often at odds with each other during that last season, things came to a head after the last game of the World Series, which the Giants lost to the Philadelphia Athletics. At a reunion of some former Orioles at a New York saloon, a drunken McGraw criticized Robinson's coaching at third base in the afternoon's 3-1 loss. Robinson snapped back that McGraw's managing had been "pretty lousy" too. "This is my party. Get the hell out of here," snarled McGraw. Not to be outdone, Robinson showered him with a glass of beer on the way out. The feud would last for seventeen years before the two aging skippers would reconcile at the National League winter meetings in 1930.

"What's the matter with me?" Babe Ruth's Called Shot: The Myth and Mystery of Baseball's Greatest Home Run,

Ed Sherman (2014)

Huggins's death rocked baseball. The American League canceled its games the following day, and the viewing of his body drew thousands of fans. The Yankees were shocked. "I'll miss him more than anyone," Gehrig said. "Next to my father and mother, he was the best friend a boy could have. He taught me everything I know." Ruth also took Huggins's death hard. He joined the ranks of the player in the clubhouse sobbing when they learned the news. "You know what I thought of Miller Huggins, and you know what I owe to him." ... The unexpected development left the Yankees reeling and looking for a manager for the firt time since 1918. General manager Ed Barrow wanted future Hall of Famer Eddie Collins, but Collins wasn't interested. Art Fletcher, a longtime coach for the Yankees, also declined an offer to run the team. Ruth, meanwhile, had the perfect candidate in mind: himself. Why not? After all, he had been playing in the big leagues since 1914. He knew the game as both hitter and pitcher. ...

Ed Barrow looks over Babe Ruth's shoulder as he signs a Yankee contract next to Colonel Ruppert. Surely Yankees owner Jacob "the Colonel" Ruppert owed him this opportunity. Managing a big-league squad was the only thing he hadn't done in baseball. Not only was he qualified, but the position would serve as a payback for all that he had done for the franchise. Ruth pleaded his case. "I told him I knew how to handle young pitchers because I had been one myself. I knew how to handle hitters because I was one myself." Ruppert resisted the idea. All those years of flaunting the team rules when he was younger, requiring both owner and manager to discipline the slugger, were coming back to bite Ruth. Ruppert, with his German accent, always pronounced the Babe's last name "Root." In turning him down, the team owner uttered the famous line that dogged the slugger for the rest of his baseball career: "You can't manage yourself, Root. How do you expect to manage others?" Ruth had a comeback, though. He wasn't a kid anymore. He was about to turn 35. He had a new wife and was raising two daughters. Ruth tried to convince Ruppert that he had matured. His wild days lay behind him. Besides, he reasoned, who else better to know whether one of the players was getting out of line. "I know every temptation that can come by any kid, and I know how to spot it in advance," he said. "If I didn't know how to handle myself, I wouldn't be playing today." Ruppert said he would consider it, and Ruth walked out of the meeting thinking that he had a chance. It turns out that he had zero chance. Not only did Ruppert not select Ruth, but the owner further offended his star by not personally informing him. Ruth learned that Bob Shawkey had filled the position through the newspaper, which he promptly threw across the room. That wasn't the end of the matter, however. Ruth writes that he "exacted revenge" from Ruppert by demanding a big salary for 1930. Initially he asked for $100,000, eventually settling for a two-year deal at an unheard-of $160,000. He also informed Ruppert that he wouldn't be as available to play in exhibitions during the Yankees' off-days, another big revenue source for the team owner. ... [The Yankees hired former P Bob Shawkey, who lasted only one year.] Shawkey's firing also proved to be another source of frustration and embarrassment for Ruth. Again, the slugger went to Ruppert, asking to be manager. He pleaded his case for a second time. "I don't think [they] realized that I had matured, was finally a grown man with family responsibilities and not the pipe-smoking playboy [Ruppert and Barrow] had pulled the covers off in that hotel room in 1919," Ruth wrote in his autobiography. Ruppert, though, recalled those moments and used them once again to deny Ruth the job. "He recited a long list of my early mistakes - he had somebody look them up-and at the end he shrugged. 'Under those circumstances, Root, how can I turn my team over to you?'" Ruth believed that if [Joe] McCarthy hadn't become available, he might have had a decent shot at the position. ... Even so, Ruth wrote of yet another snub: "It still hurt," and that hurt lingered for the rest of his life. He desperately wanted to be a manager. Ruth wanted the authority. He wanted to show that he could be a leader of men. But no one had faith in him to do so. In 1933 he fumed when the Washington Senators named Joe Cronin as a player-manager. Cronin was all of 26 years old. "It made me scratch my head and wonder if I'd ever be mature enough to become a manager," Ruth snarked. He also wrote that Detroit owner Frank Navin had asked if he might be interested in managing the Tigers after the 1934 season. Ruth said yes and asked if he could talk after he returned from a barnstorming commitment in Hawaii. Navin was put off by Ruth's inclination to honor his commitments. Instead, after spending $100,000 to buy Mickey Cochrane from Philadelphia, Navin made the catcher the new manager. "In looking back, I can't help but wonder whether those pennants would have gone to me instead of Mickey if I had run out of the first part of my Hawaiian contract," Ruth wrote. Ruth was so desperate, he even signed with the lowly Boston Braves in 1935 because of a promise that he would become manager. He soon realized though, that the Braves had no intention of letting him run their team. Jilted and with his skills totally gone, Ruth retired after player only 28 games. Rickey's Big Mistake Yogi Berra: Eternal Yankee,

by Allen Barra (2009)

Sometime in the summer of 1941, two of the great legends of baseball narrowly missed making a connection that would have radically altered baseball. ...

Lawrence Peter Berra, a then somewhat stocky, ungainly looking sixteen-year-old Italian-American kid from the "Dago Hill" area of St. Louis, had attracted the attention of the best organization in the National League for a tryout in Sportsman's Park. Jack Maguire, a scout for the St. Louis Cardinals told his boss, general manager Branch Rickey, that Berra had a powerful left-handed swing, a great arm, and heaps of potential. Rickey wasn't sure; he was more interested in another kid from the Hill, Joseph Henry Garagiola, a year younger than Berra. Garagiola was thought by Rickey to be faster, smoother, and more polished. Dee Walsh, another Cardinals scout, talked Rickey into signing Garagiola with a $500 bonus, but Rickey was skeptical about offering anything at all to Berra. Rickey had been getting reports on both boys all summer, not just from his scouts but also from two of his outfielders, Enos Slaughter and Terry Moore, who occasionally showed up to give pointers at the WPA baseball school at Sherman's Park. Rickey's initial offer to young Berra was a contract - but no bonus. To a boy that age, a professional baseball contract, even without a bonus, was nothing to be scorned. But Lawrence, displaying the kind of stubborn integrity that would, in just a few years, stymie the most powerful organization in sports, balked. "In the first place," he would tell sportswriter Ed Fitzgerald nearly two decades later, "I knew it was going to be tough enough to convince Mom and Pop that they ought to let me go away. But if Joey was getting $500 for it and I wasn't getting anything, they would be sure to think it was a waste of time for me."   L: Branch Rickey; R: Yogi Berra and Joe Garagiola Jack Maguire argued with his boss, but Rickey was intractable: Berra would never be more than a Triple-A player. He was too clumsy and too slow, Rickey said, to be a genuine big league prospect. Maguire never understood Rickey's decisions. Berra's coaches, and certainly his opponents, did not find him either slow or clumsy, though he often appeared to be both. ... Rickey had been a catcher himself and was capable of evaluating all body types. He understood that baseball was a game that benefited from all manner of physical tools. Yet, Rickey, against the advice of his own scout, would not put out the additional $250 to sign Larry Berra. It was the most colossally shortsighted blunder ever made by a baseball executive, surpassing even Boston Red Sox owner Harry Frazee's dealing Babe Ruth to the Yankees in 1920 ... If, that is, Rickey's decision was a blunder. In later years, a counterstory would circulate that Rickey was actually being shrewd: he knew he wouldn't be with the Cardinals much longer, he was preparing to leave the St. Louis club for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and his real interest was to "hide" Berra and sign him for Brooklyn. Joe Garagiola points out that just a couple of months after the tryout, after Rickey had moved to the Dodgers, he contacted Berra to offer him a contract. "Rickey tried to sign Yogi after he went to work for the Dodgers," says Joe. "Why would he have kept a file on him if he hadn't intended to sign him for Brooklyn?" In his 1961 ... autobiography ..., Yogi flat-out denied that Rickey had tried to "hide" him. "I've never believed that ... From everything I've heard about him, he's too big a man to do anything like that." ... The New Bat Cured the Stomach Baseball's Great Moments, Joseph Reichler (1974)

Willie McCovey, not an easy fellow to intimidate, was scared half to death. A loud thud had awakened him in the middle of the night. He leaped out of bed, switched on the light, and found his roommate, Willie Mays, lying on the floor. Willie had fallen out of bed and blacked out. McCovey summoned the club trainer, Doc Bowman, who revived Mays, gave him some pills, and got him back into bed.

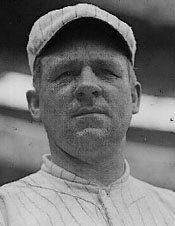

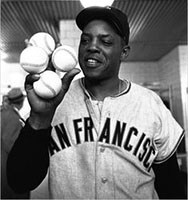

That was early in 1961. The Giants had arrived in Milwaukee for a three-game series with the Braves, and Willie Mays was in a batting slump. He went hitless in seven times at bat in the first two games. In one of those games, Warren Spahn threw a no-hitter at the Giants. Spahn remarked afterward that he had never seen Mays look so bad at the plate. "I could tell that something was bothering him," Spahn remembers. "He looked like he was having trouble holding up his bat."    L-R: Willie Mays, Joe Amalfitano, Jim Davenport

Spahn was right. Willie had had a persistent stomach ache. Nonetheless, the night before the final game of the series with Milwaukee, he and McCovey went for a midnight snack, and Mays, ignoring his stomach, decided on barbecued spareribs. He should have known better. Afterward, he couldn't fall asleep. He began having sharp pains in his stomach. He became nauseous. That was the night McCovey found him unconscious on the floor.

Mays felt a little better the next day, but he didn't hit the ball well in batting practice. Joe Amalfitano, a teammate, suggested he try his bat, which was a little heavier than Willie's. Mays felt a little more comfortable at the plate by the time the game started. Lew Burdette, always a tough pitcher for Mays, was on the moud for the Braves. He threw Mays a slider, and Willie hit it over the fence in left center, 420 feet away. So much for not feeling well. The same thing happened the next time Mays came to bat, in the third inning. This time the ball traveled about 400 feet. When Mays came up for the third time, Seth Morehead was pitching for the Braves. He threw Willie a sinker, and Mays really caught hold of it. The ball landed in dead center, over the fence, out of the park, and beyond the trees. Writers estimated that the ball traveled at least 450 feet. Moe Drabowsky, a right-hander, faced Mays the fourth time. Willie connected again but didn't get the ball high enough, and it went for a long line drive out to center field. In the eighth inning, Don McMahon, a flame-throwing righthander, was pitching for Milwaukee. He threw Mays a slider and Willie desposited it in almost the same spot that the third homer had landed. It was his fourth home run of the game and tied the major league record. Only eight other players since the turn of the century had hit four home runs in a game, only four others in a nine-inning game. Mays drove in eight runs. One homer came with two on base, two with one on base, and one with none on. The last player to hit four homers in a game had been Rocky Colavito in 1959. No player has hit four homers in a game since Mays. Mays just missed a chance for five. Jimmy Davenport, who batted in front of him, was hitting in the ninth with two out and the crowd yelling for him to get on base. One might have thought they were playing in San Francisco instead of Milwaukee. Davenport bounced out to end the inning. "In a way, I'm glad Jimmy didn't get on," Willie says. "I'm not saying I wouldn't have liked a shot at a fifth home run, but I don't think I could have done it. I would have been pressing, knowing I could set a record that might never be equaled. I knew what I had done. I heard it over the loudspeakers. "That was easily the greatest day of my life. I was already beginning to feel nervous waiting on deck. Funny thing, I wasn't nervous when I hit the fourth home run. That's because I never dreamed I'd hit it. I know I wasn't trying for it. I was just swinging. You're satisfied if you get two in a game, but when you get three, that's something you never expect. Four? That's like reaching for the moon." Willie's stomach ache had gone. One Pitch Away: The Players' Stories of the 1986 LCS and World Series,

Mike Sowell (1996)

Gene Mauch managed the 1964 Phillies, who had a 6.5-game lead with 12 games to play and blew the pennant.

Mauch ... was the boy wonder of baseball managers. Thirty-eight years old, and he had the hottest ball club around. Five years on the job, and he had turned a bunch of losers into winners.

L-R: Eddie Sawyer; John Quinn, Gene Mauch

The Phillies — everyone in baseball knew about them. In the words of Philadelphia columnist Sandy Grady, "The team's feature was the 'Dalton Gang,' boozy nightriders who set records for demolishing saloons."

The Phillies also were adept at losing games. Two last-place finishes in a row. Eight years since their last winning season. Ten years earlier, when they won their last pennant, the youthful Phillies had been known as the "Whiz Kids." These aging and inept Phillies were the "Whiff Kids." Mauch jumped at the offer. It didn't take him long to start cleaning up the ball club. He weeded out the troublemakers. He laid down his set of rules and enforced them with tough words and tough actions. "Managing that team wasn't the hardest part," Mauch later told Grady. "First, you had to go into bars or bust down hotel doors to find them. It's a good thing I was a young man. An old one would never have survived." But Mauch survived. And he taught his Phillies to play winning ball. Success did not come overnight, and in 1961 Philadelphia set a major-league record by losing twenty-three games in a row. But even in those losing years, the Phillies were coming together as a ball club. Slowly, Mauch began to piece together the kind of team he wanted. It was a team of scrappers and hustlers and hard-nosed ballplayers. They moved up to seventh in 1962, fourth in 1963. They would go on the field to warm up before a game, and with every throw by a Philadelphia outfielder, the bench players would shout at the opposition: "You ain't got no arms like those!" The Philadelphia hitters would take batting practice, and those waiting their turn at the plate would yell toward the enemy dugout: "You ain't got guys who can hit like they can!" And Mauch, the team's ringleader, never missed a trick. In right field was a corrugated iron fence that balls bounced off at crazy angles. So, Mauch moved his bullpen from left field to right and had his spare pitchers use towels to signal the Philadelphia base coaches how balls were going to strike the fence. This enabled the Philadelphia base runners to know when to take an extra base and when to stay put. Mauch shaved down the pitcher's mound to help his pitchers. He schemed and plotted from the dugout, once sending up seven pinch hitters in a row, another time putting three pitchers in his starting lineup. He changed pitchers while the same batter was at the plate to get the results he wanted. No one knew the rules better than Mauch did. When an opposing catcher reached into the Philadelphia dugout to catch a pop foul, Mauch karate-chopped his arm to knock the ball loose. An argument ensued, but Mauch prevailed. The rule book stated that a player enters the other dugout at his own risk. Mauch also used his fierce temper to motivate his players. In a celebrated incident in Houston late in the 1963 season, he reacted to a ninth-inning loss by knocking over the postgame buffet and throwing a pan of spare ribs across the locker room. What people overlooked was that after that outburst, the Phillies won five of their final six games to squeeze into fourth place, earning each player on the squad an additional seven hundred dollars. The Bronx Zoo The Bronx Zoo: The Astonighing Inside Story of the 1978 World Champion New York Yankees,Sparky Lyle with Peter Golenbock (1979)

I was on a team that won the pennant and the World Series, despite enough crap to last an entire career, and now that I've won the Cy Young Award everyone can say that Sparky Lyle was an important part of that team. ...

The best thing that happened to me was finishing the final two games of the play-offs against Kansas City and right after that winning the first game of the World Series against the Dodgers. The Royals were leading us in the play-offs, two games to one, and they needed only one more game to win. In the fourth game we were ahead 4-0 real quick, but in the fourth Reggie Jackson screwed up a couple of balls in the outfield, the Royals scored two runs, and with two outs and a runner on, Billy [Martin] brought me in. Ordinarily the fourth inning is much too early to bring me into a game. I'm a short relief pitcher. I pitch in the eighth and ninth when there's a lead that has to be protected. I'm the last resort, the guy who has to put his finger in the dike every night. But I guess Billy was desperate, so he brought me in in the fourth. As I was warming up in the bullpen, Fred Stanley, our backup shortstop, was catching me, and when pitching coach Art Fowler called from the dugout and asked how I looked, Fred told him, "Sparky ain't got nothin', Art." Billy brought me in anyway, and when I got out to the mound and threw my warm-up pitches, my slider suddenly started to work right, and for the next five innings, it was the Royals who didn't have nothin'. I faced 16 batters and got 15 outs.

L-R: Sparky Lyle, Reggie Jackson and Billy Martin I knew that the Royals weren't going to beat me. I had told [my wife] Mary, "I can't pitch in games when we're real far behind or ahead. I'm just not into the game." ... The best time for me to pitch is when we're ahead by a run or the score is tied. When the game is on the line. Against the Royals I was ahead by a run, and Mary was telling me that she was sitting in the stands watching me, and when everybody was hollering for the Yankees to score a few more runs, she was thinking, "No, I don't want them to score more runs." Later she told me, "I knew you weren't going to lose that game. You only had a one-run lead." And she was right.

After the game, the writers asked me, "Can you pitch again tomorrow?" I said, "Only four or five innings. After that, I might start getting tired." They laughed. They must have figured I was joking. We were losing 3-2 going into the top of the ninth of the final game. Paul Blair singled. Roy White walked, and Mickey Rivers singled up the middle to drive in a run to tie it. Willie Randolph drove in Roy with a long fly to put us ahead, and after we scored a fifth run, Billy brought me in to pitch the bottom of the ninth and end it. I got the first guy out real quick, then the next guy up got a base hit. We were in Kansas City, and with Freddie Patek, their shortstop, up, everybody in the stands was ranting and raving and going crazy. Thurman [Munson] dropped the sign down, I threw Patek a slider, and he hit a nice one-hopper to Graig Nettles at third, and that was it. A perfect double-play ball. Graig didn't even have to move. He caught it chest high, threw to Randolph at second, and bang, bang, it was over. All I remember is raising my arms high and jumping straight up in the air. Thurman started hugging me, and then there was a big pile of players around me. It was a great feeling, because we had battled our asses off to win that pennant. ... All season long, we never gave up. ... Also, what was important to me about our winning that game was that if we had lost, I am convinced that George Steinbrenner ... would have fired Billy. There had been talk the last couple of weeks, yet despite the talk, Billy still benched Reggie Jackson in the final game, because the Royals were throwing a tough left-handed pitcher, Paul Splittorff, and Reggie doesn't hit the tough lefties. Billy knows that, too, and he decided to play Blair instead. Ordinarily it's no big deal when a manager does something like that, but last winter George had paid Reggie $2,930,000 to play for the Yankees, and George wasn't paying Reggie all that money to sit on the bench. When we heard Reggie wasn't going to start, we thought, "This guy" - meaning Billy - "has some balls." But then again, Billy and George had been fighting all year, usually after a fight between Billy and Reggie. And talk that Billy was going to get fired had popped up so often that after a while we stopped paying any attention to it. It was getting in the way of our playing. When Billy benched Reggie against Splittorff, my only reaction was "We'll be a stronger team with someone else playing right field and with someone else batting fourth against this guy." With him or without him, I knew the Royals weren't going to beat us.

Wacky Weather and Gnashing Gnats

"Elements of Style," David Moran, Memories and Dreams: Official Publication of the Baseball Hall of Fame (Summer 2016)

The weather, the world and the wacky have all played a part in baseball history.

As Yankees pitcher Joba Chamberlain came in to protect a 1-0 Yankees lead in the eighth inning, a swarm of bugs surrounded his head and refused to leave. Team trainers sprayed Chamberlain between pitches to no avail. The relentless insects so unnerved him that he came unglued and blew the lead with two untimely wild pitches. The Indians won the game and eventually the series, thanks in part to the pesky behavior of an insect called midges.

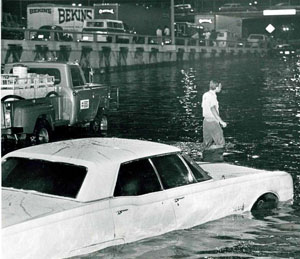

On June 15, 1976, the Astros were scheduled to play the visiting Pittsburgh Pirates in an evening game. Shortly before noon, the skies opened up and a torrential downpour engulfed Houston. Downtown received 7.48 inches of rain by game time, and an unofficial reading near the Astrodome measured 10.47 inches. Streets all around the ballpark were flooded and by late afternoon it was impossible to get to the game.

Ironically, all players from both teams were in the house, having arrived early for pregame practice, and consideration was given to playing the game without fans. That idea was scratched when the umpires called and reported they had attempted to reach the stadium but their car stalled on flooded roads. The men in blue abandoned their vehicle and waded back to their hotel.  Houston flood of 1976 Can't-Miss Hall of Famer

Memories and Dreams: Official Magazine of the Hall of Fame, Mike DiGiovanna (Spring 2018)

Vladimir Guerrero's Prowess at the Plate Amazed Teammates and Opponents

The stories, as many as there are, simply don't do justice to the hitting skills of Vladimir Guerrero. Those who played with and against him still tell tales in amazed tones. "I was in CF, and the C put down four fingers for a pitchout," said All-Star CF Torii Hunter, who was playing against Guerrero in Double-A in 1996. "Vladdy reached out and hit a homer to right-center. We had a pretty tall wall, and as I'm running, I could not believe it went out of the park. I'm like, 'Who is this guy?'"

"The only time we got him out was when we threw a pitch down the middle," joked Hunter. "We'd pitch around him, and he'd be eight-for-nine in the series." Guerrero, elected to the Hall of Fame in January 2018 ..., spent a career regularly doing the impossible. One of six brothers and sisters raised by a single mother, Guerrero grew up in Bani, a dusty provincial capital with a population of 72,500 near the Dominican Republic's southwestern coast. He lived in a shack with no electricity or running water, and after a hurricane blew its tin roof off, the family squeezed into a single room and shared two beds.   When his older brother, Wilton, received an invitation to a Dodgers training camp on the island, 16-year-old Vladimir tagged along, claiming he was a year older to secure a tryout. Though he was a gangly 6-foot-3 with a clumsy gait and an unorthodoz swing, Guerrero's raw skills and athleticism were obvious. He had a rocket for an arm, a gazelle-like stride and was long enough to hit outside pitches with authority. But that legendary story that Guerrero wore mismatched shoes for that workout? Not true, Guerrero said with a chuckle. "Yeah, the shoes didn't fit well, and I looked like I was running on marbles, but the fact is, I wore those shoes for a long time," he explained. "I did not wear left shoes on both feet." Guerrero eventually signed with Montreal for $2,500 as an 18-year-old in 1993. He shot through the farm system and arrived in the big leagues in September 1996. In his third game, facing veteran Atlanta closer Mark Wohlers, Guerrero smacked a first-pitch low-and-away fastball over the RF wall for a homer. It was the first of many. Guerrero played seven seasons in Montreal, batting .323 with a .978 OPS, 234 homers and 702 RBI. He then spent six seasons with the Angels, hitting .319 with a .927 OPS, 173 homers and 616 RBI before closing his career with a year in Texas (2010) and then Baltimore (2011). Guerrero, a career .318 hitter with 2,590 hits, led the Angels to five division titles. He won the AL MVP Award in 2004 in his first year with the Angels - after a torrid end of the season that saw him hit .363 with 11 homers, 25 RBI and 25 runs over the final 30 games. Scouting reports on Guerrero were basically useless. Don't throw him a strike, most of them said. And don't throw him a ball. He hits those even harder. "I remember Todd Stottlemyre bouncing a split-fingered pitch that Vladdy hit for a double," fellow Dominican Hall of Famer Pedro Martinez said. "I was like, 'Oh my God, did I see that? Did that ball bounce?' Yes it did, and he hit if off the wall the CF. Anything low, up, in or out, it didn't matter. Vladdy had no strike zone. He was one of the most difficult guys to face." The years on Montreal's artificial turf took a toll on Guerrero's lower back and knees, and he spent most of his final four seasons at designated hitter. But in his prime, Guerrero was one of baseball's best right fielders, with the instincts and range to run down balls in the gap and the arm to gun down runners on the bases. He had 126 outfield assists. His rare two-way skills paved the way for him to become the first Dominican-born position player elected to the HOF. ... The Angels, entering their 58th year of existence, did not have a player enshrined in Cooperstown with their cap until this year. In Guerrero, they have a worthy first. "Who better to go in and represent the Angels than Vladdy, a guy who was a great teammate, kept his nose clean and never messed up the Angels name," Hunter said. |

CONTENTS Was the '19 Series the First Rigged One? Wacky Weather and Gnashing Gnats

|

Joba Chamberlain vs the Gnats

Joba Chamberlain vs the Gnats