|

Foreshadowing Ray Chapman 1921: The Yankees, the Giants, & the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York,

Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg (2010) It was no secret that [Yankees manager] Miller Huggins had a fondness for the Baltimore kid Chuck Fewster. Maybe Huggins identified with the skinny, almost gaunt, infielder. "Chick has everything," Huggins had said when he first evaluated Fewster before the 1918 season. "I have never seen a greater prospect." Fewster had many fans rooting for him as he was attempting a comeback from a near-fatal beaning in spring training 1920.

In an eerie foreshadowing of Ray Chapman's death, a fastball from Brooklyn's Jeff Pfeffer had fractured Fewster's skull in a game in Jacksonville, Florida, on March 25. Like Chapman, Fewster had a reputation for crowding the plate. In both cases, the damaging pitches may have been strikes. In 1919 Fewster had been hit by pitches seven times. Like Carl Mays, Pfeffer was among those pitchers who hit many batters (he had hit fifty men from 1915 to 1917); they both had led their leagues in that category in 1917.

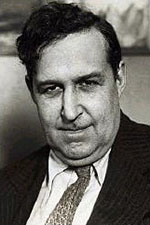

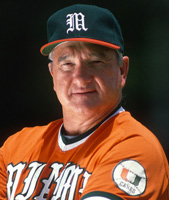

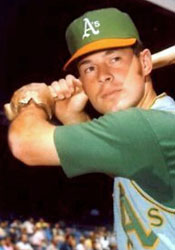

L-R: Miller Huggins, Chuck Fewster, Jeff Pfeffer Originally, Fewster's injury was not deemed life threatening. Yet he could not talk, an indication that his vocal chords might have been paralyzed. The Yankee owners insisted that he return to Baltimore, his home and the home of Johns Hopkins, one of the nation's top hospitals. Doctors at Hopkins diagnosed Fewster's worsening condition, operated to relieve the swelling and bleeding in his skull, and saved his life. While many newspapers predicted that his career was over, Fewster did return to play in 1920, albeit with only twenty-one at bats. Huggins planned to play him at second base and in the outfield in 1921, as he had in 1919 when Fewster hit .283. Fewster was offered a few "head guards" made of cork and felt in the spring of 1921, but he refused them all. Observers were wondering if he would be plate shy, since many previously beaned players could not avoid the urge to pull out of their batting stance as the ball approached. Yet when he faced Pfeffer almost a year to the day after the beaning, it was the pitcher who seemed tentative, not his former victim. Fewster crushed Pfeffer's first pitch for a triple. "There are many kinds of courage in this world. Chick Fewster possesses all the kinds there are," wrote James P. Sinnott in the New York Evening Mail.

Dizzy Exhibition Game Pitcher

"The One and Only," Jack Sher, Sport Magazine (May 1948)

A name can be born in a moment. It takes action to make it mean something, to breathe life and color into it. Diz gave it that life. A lesser man might have resented the name "Dizzy," but not a guy like Dean. Even then, this warm, lovable, uneducated (but wise) kid understood that baseball is more than mere auotmatons who can hit, catch, or pitch. He knew that the game is also the personalities of the men who play it, their diverse backgrounds and peculiarities. As his onetime brilliant teammate, Pepper Martin, said: "When ol' Diz was in there pitching it was more than just another ball game. It was a regular three-ring circus and everybody was wide awake and enjoying being alive." Even as Jerome Herman Dean, his big right arm undoubtedly would have made him a great winning pitcher. But as Dizzy Dean, he was more than that. He was a tremendous, exciting personality, a strictly screwy, magnificently American character, an advertisement for baseball, an attraction that drew to the game those hitherto unfortunate people who didn't know a scratch hit from a double steal. A Radical Proposal

Bill Veeck: Baseball's Greatest Maverick, Paul Dickson (2012)

The Great Depression had a devastating effect on Major League Baseball just as it had on all of American society. That effect caused some to offer unheard-of proposals.

On February 5, 1933, ... the grand ballroom of New York City's Commodore Hotel hosted more than 600 of the game's leaders ... and all the National League officials in town for their annual meeting - at the tenth annual New York Baseball Writers' Association of America dinner. It was a night of fun, frolic, and frivolity. Sportswriters took turns spoofing everyone from the guest of honor, retired New York Giants manager John McGraw, to the New York Yankees, who had won the World Series in October. In addition, the scribes performed their annual blackface minstrel show in front of the predominantly white crowd. New York Times sportswriter John Drebinger in his column the next day called the minstrel show the most entertaining part of the evening but never mentioned its most dramatic moment. Heywood Broun, a talented and outspoken Scripps-Howard columnist who was asyndicated in dozens of newspapers and admired by his fellow writers, offered a full-blown proposal for racially integrating baseball, arguing that the game's falling gate receipts could be reversed by dropping its invisible "color line." Branding baseball's segregation as "silly," Broun asked rhetorically: "Why, in the name of fair play and gate receipts, should professional baseball be so exclusive?"

Invoking the name of a man who was one of the leading actors, singers, and activists of his time, Broun continued: "If Paul Robeson is good enough to play football for Rutgers and win a place on the mythical All-America eleven, I can't be convinced that no Negro is fit to be a utility outfielder for the Boston Red Sox. There were a number of superb Negro athletes on the American Olympic track team. indeed, Eddie Tolan, the sprint champion, was almost a team in himself. ... If Negroes are called upon to bear the brunt of competition when America meets the world in an international meet, it seems a little silly to say that they cannot participate in a game between the Chicago White Sox and the St. Louis Browns."

Broun addressed head-on the concern that some players would object to racial integration, but then dismissed it by pointing out that ballplayers objected to many things that still took place with a high degree of regularity, such as fines, suspensions, and the widespread salary cuts being imposed for the upcoming season. Bill Gibson, a writer for the Baltimore Afro-American and one of a handful of writers from the Negro press at the dinner, found a number of people who expressed an open mind on the subject, including Branch Rickey of the St. Louis Cardinals, Yankees slugger Lou Gehrig, and John Heydler, president of the National League.

A few weeks later, the popular Dan Parker, sports editor of the New York Daily Mirror, wrote a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier fully endorsing an end of the color bar, insisting that club owners who welcomed the patronage of black fans had no right to bar black athletes. "In my career as a sports writer," Parker added, "I've never encountered a colored athlete who didn't conduct himself in a gentlemanly manner and who didn't have a better idea of sportsmanship than many of his white brethren. By all means, let the colored ballplayer start playing organized baseball."

Major League Baseball would not be integrated until Branch Rickey called up Jackie Robinson to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, 13 years after the incident cited above. Mrs. Rickey Says No

Rhubarb in the Catbird Seat, Red Barber and Robert Creamer (1968)

GM Larry MacPhail had hired Red Barber to announce the Cincinnati Reds games, About then - the fall of 1942 - Larry MacPhail announced that he was leaving the Dodgers to go into the Army. ...

I was no party to the high-level discussions by the Brooklyn board and I had no idea what was going to happen, but the next thing I knew Branch Rickey had severed himself from the job with the Cardinals in St. Louis and was installed as MacPhail's successor at Brooklyn. I was delighted. Rickey came east and with Mrs. Rickey took a furnished apartment in Bronxville ... only a few miles from where Lylah and I were living ...He had not been in the apartment in Bronxville very long before he called up and asked us to come visit. Lylah had never met the Rickeys. ... We went down for Sunday luncheon and it was very pleasant. Unless you were around the warm magnetism of Mr. Rickey in the bosom of his family in his own home, you really don't know what charm is. Mrs. Rickey was a doll, a living, breathing doll. She was just as much a personality in her own right as he was. Rickey, with all his strength and ability, never got one step ahead of Mrs. Rickey in all of his life, never once. I think maybe one of the reasons why Rickey went so far and so fast was because he had to set a gait according to his wife, and that was a pretty fast pace.

L: Red and Lylah Barber and their daughter Sarah R: Branch and Jane Rickey and their son Branch Jr. So he would talk things over with Mrs. Rickey. She was his sounding board. She would listen, and then she would give her reactions. She had strong opinions, and she was not the least hesitant about giving them to this man. He did not always follow her advice or agree with her opinion. For instance, she told him not to start the Jackie Robinson thing. She told him that he had no business getting into that at his age, stirring up all of baseball and all of the country and maybe getting into a thing he would never get out of until he went to his grave. As we used to say in Brooklyn, she left him have it about breaking the color line and bringing a Negro into baseball. She detailed the complications, the complexities, and ramifications, of what he planned to do. That was a long time before anybody knew Jackie Robinson's name - and I mean even in the Rickey household. Branch Rickey decided to bring Jackie Robinson into baseball two years before he knew who Jackie was. Jackie was the individual who emerged from the principle. Mrs. Rickey was against the idea, and their six daughters and their only son asked Rickey to leave the thing alone, that he had enough going, that he was too old to take this problem on his hands. That was something, to have opposition, and reasonable opposition, from the people closest to him, the ones he loved, the ones whose opinions mattered beyond all others. But he went ahead anyway. Rickey wasn't headstrong much when he got that bit in his teeth, was he?

Ted's Frustrated The Victory Season: The End of World War II and the Birth of Baseball's Golden Age,

Robert Weintraub (2013) The Red Sox were having difficulty clinching the 1946 American League pennant. One of the reasons for their failure was that their main hitter was mired in a slump.

Boston had saved its worst for last. The celebratory champagne was being carried across half the American League, from Washington to Philly to Detroit to Cleveland, without being cracked open. There was no thought of an epic collapse (they still led the AL by fourteen games), but the wait at the precipice was getting on the nerves of everyone in Boston.

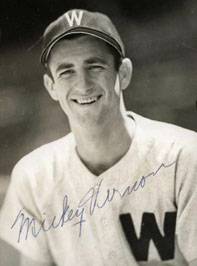

Williams was getting on people's nerves himself. Throughout his career, he would often wear down toward the end of the season due to illness. Even as a kid in San Diego, late-summer fevers plagued him, though he never did figure out why. Now he spent many a ball game in a fog, from either a head cold or the medication he took to treat it. "He practically had pneumonia, he was so sick," remembers Bobby Doerr. "He was real run down." "I'm tired physically," Williams admitted to the press late in the season. "I'm on the go all the time and I wish it were all over." Meanwhile, his Triple Crown hopes had dissipated like a sneeze in the air. Once the leader in all three categories, he fell behind Mickey Vernon of the Senators in the batting chase, and Hank Greenberg, Detroit's slugging star in the twilight of his fabled career, in home runs and RBIs. Greenberg had suffered through a miserable 1946. He had been the first major league star to be called up for service, way back in 1940. He was honorably discharged on December 5, 1941. Two days later, he was back in the military, volunteering (the first major leaguer to do so after Pearl Harbor) for the Army Air Corps. "We are in trouble," he told the Sporting News, "and there is only one thing for me to do - return to the service. This doubtless means I am finished with baseball and it would be silly for me to say I do not leave it without a pang. But all of us are confronted with a terrible task - the defense of our country and the fight for our lives." ... He came home in mid-'45 and proved he was far from "finished with baseball." Greenberg walloped a homer "on a line as flat as old beer," in Red Smith's phrase, during his first game back, and hit a grand slam to clinch the pennant. Hebrew Hank then slugged a memorable three-run shot to win Game Two of the World Series, as the Tigers bested Chicago in seven. But for most of the summer of '46, he was considered washed-up at age thirty-five, his 28 homers, 88 RBIs, and .268 batting average through August far below his standard numbers. Then a fellow Tiger, an even older one named Roger "Doc" Cramer, who at forty was fortunately still extremely juvenile, slipped into the Sox clubhouse one afternoon at Fenway and stole one of Ted's bats. Cramer presented it to Greenberg, and Hank duly, in his words, "embarked on his annual fall salary drive" with the new lumber. He smashed a dozen homers in three weeks with Splinter's splinter, until it shattered one day. Undaunted, Hank hit 5 more with his own previously uninspiring ash, to give him 16 for the month of September and 44 in all, good for best in the league. His 39 RBIs during the exceptional month gave him that title as well. Grantland Rice opined, "Greenberg's surge is one of baseball's greatest achievements." When the season ended, he gave Williams a fresh bat as a thank-you.   L: Mickey Vernon; R: Hank Greenberg presents a bat to Ted Williams after 1946 season.

Ted wasn't too happy about the whole thing. He suspected, as did some others, that Greenberg and Vernon were getting grooved pitches in an effort to deny Williams the Triple Crown. As Austin Lake wrote, "Rival athletes gradually grew sour at Ted for his aloof swagger and chill hauteur toward his fellow craftsmen." Pitchers, in the Williams worldview, were dubious characters who lacked morals. He could easily envision some of those snakes not coming high and hard at the popular Greenie so they could stick it to The Kid.

The Sox soon clinched the pennant. Ted did not lead the AL in any of the Triple Crown categories but was overwhelmingly voted MVP.

"I Decided to Cheat" Slick: My Life In and Around Baseball, Whitey Ford with Phil Pepe (1987)

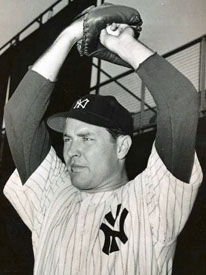

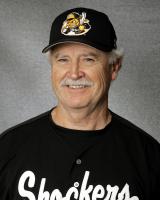

I felt I was nearing the end of my career. My slider was not as fast and I had lost a little off my fastball. ... I had to come up with a new pitch. I decided to cheat. I had experimented with a spitball earlier in my career, even tried it a few times in games, but I never could perfect it. Joe Page taught it to me when I was just breaking in with the Yankees. ... Lew Burdette had the reputation of throwing the best spitter in baseball. ... I went to Lew before a game one day ... I asked him if there was anything he could suggest. He was only too happy to help. "I'll show you how to throw it even though I don't throw it myself," Lew said with a straight face. ... Burdette showed me how to apply mud to the ball so it would dip and dart. I tried it on the sidelines and I couldn't believe the movement I was able to get on the ball. This was the new pitch I was looking for. All I had to do was perfect it and figure out how to do it so it wouldn't be picked up by the umpire or the opposing players and managers. What I did was spit in my left hand, which was perfectly legal, then pretend to rub up the ball. Also legal. But I wasn't really rubbing up the ball at all. Only one hand was moving, the hand that was dry. The hand with saliva on it was not moving, and saliva was being transferred from the hand to the baseball while the dry hand was rotating around the ball. ... Now the saliva was on the ball, and the next thing I did was reach down and pick up the resin bag with the hand that still held the baseball. As I grabbed the resin bag with my thumb and forefinger, I gently touched the baseball on the dirt on the mound. I had to make sure that the portion of the ball that was wet with saliva hit the dirt. What would happen is that the dirt would stick to the wet baseball. Now I was "loaded up" and ready to throw my "mud ball" or "dirt ball." I threw it just like my fastball, as hard as I could. If I kept the dirt on the top when I released the pitch, the ball would have the action of a screwball. It would move away from a right-handed hitter and it would sink. It became a very effective pitch for me. The hitter was never the wiser, because unlike the spitter, the mud ball would be rotating when it came up to the plate. A spitball comes in more like a knuckleball, with no rotation, and the bottom just drops out of it at the last moment. Since my "mud ball" had rotation on it, nobody ever suspected me of throwing a funny pitch. ...    L-R: Whitey Ford, Joe Page, Lew Burdette I was never caught throwing the mud ball. ... If somebody asked the umpire to check the ball after I had "loaded" it up with mud and before I pitched, just as I was reaching up to throw it to the umpire, I would hit the ball on the side of my pants leg and the mud would come off. ...

Once I started getting away with the mud ball, I started experimenting with other things. I guess I got bored and I needed a new challenge. I found I could get the same action on the ball by scuffing one side of it, or by nicking the baseball on one side. All of a sudden I was getting pretty sophisticated in my cheating. I figured it didn't hurt a pitcher to have more than one pitch in his repertoire. Besides, if they ever caught on to one of my tricks, I had to have another one to take its place. I had this friend named Joe Piser. ... I asked him if he could get his jeweler friend to make me up a ring with a rasp attached to it. I figured I could wear the ring and cut the baseball with the rasp. ... About two weeks later, Joe presented me with a stainless-steel ring. Welded onto the ring was a rasp ... It was exactly what I wanted. ... I started wearing the ring when I pitched. I would put the part of the ring with the rasp underneath my finger. On top, I covered the ring with flesh-colored Band-Aids, so you couldn't tell from a distance that I had anything on my finger. Now it was easy to just rub the baseball against the rasp and scratch it on one side. One little nick was all it took to get the baseball to sail and dip like crazy. It was even more effective than the mud ball. Elston Howard, my catcher, had a pretty good idea what was going on, but even he didn't know how I was doing it. Joe Pepitone, our first baseman, tried to help. One time I had the ball fixed just the way I wanted it. I threw the damnedest sinker you can imagine and the batter just barely got a piece of it and trickled it foul along the first-base line. Pepi picked up the baseball, looked at it, and tossed it to the first-base umpire. "Here," he said, "this ball's no good. It's all scratched up." Later when I retired the side and returned to the dugout, I went up to Pepi. "Listen, you jackass," I told him, "If you ever hand one of my balls to an umpire again, I'm going to hit you right in the head with it." Once we were playing the Chicago White Sox and I was cutting baseballs with my ring, and Al Lopez, the Sox manager, started complaining to the plate umpire, Hank Soar. ... So Soar came out to the mound and said, "What have you got on your hand?" "It's just my wedding ring, Hank," I said. "I have it covered with a Band-Aid so it doesn't reflect in the batter's eyes." I was afraid he was going to ask to see it, so I tried to hide the cutting side as best I could. "Well, take it off," he said. ... Later Lopez was talking to the press about it. "He said he was wearing his wedding ring," Lopez said sarcastically. "Well, I love my wife, too, but I always take my wedding ring off and put it in a safe place when I put on my uniform." ... Another time, we were playing Cleveland and Alvin Dark was their manager. I noticed any time a foul ball was hit near the Indians' dugout, it would never be thrown back into the game. What Dark was doing was gathering the baseballs as evidence. Later in the game, he had collected about six baseballs, all with scratches on them in the same place, and he showed them to the umpire. The umpires never said anything to me, but after that I cooled it for a while and didn't cut the baseball until the heat was off. ... I used the ring until I retired. ... I used to do a few other things, too, which also went undetected. Occasionally, I would quick-pitch a hitter, catch him between practice swings or when he wasn't ready. ... Another thing I found I could get away with and never be caught was pitching in front of the rubber. I did that a lot and nobody ever caught on. If you covered the rubber up with dirt, it was easy to do. It's just something nobody's ever looking for. The Grand Illusion

The Road to Omaha: Hits, Hopes, and History at the College World Series,

Ryan McGee (2010) Ron Fraser turned the University of Miami baseball program into a national power. Fraser's '82 Canes blew into Nebraska with brutally ugly Houston Astrostyle horizontally striped polyester pullover jerseys, shown in glorious orange and green on ESPN, who was televising all fourteen CWS games for the very first time. In Game One, the Canes beat Maine 6-1. ...

During a quiet off-day practice at Boys Town, Fraser huddled with his assistant coaches, Skip Bertman and Dave Scott, to try and figure out how they would counter the Wichita State Shockers and coach Gene Stephenson's legendarily aggressive running game.

The assistants had an idea. While scouting at a junior-college tournament earlier that winter, Scott had watched West Palm Beach Junior College run a complicated-looking yet actually very simple hidden-ball trick. He walked Fraser through it and Fraser immediately began to choreograph a version right there on Father Flanagan's old ball field. The Canes ran the play a few times on the high school diamond, each repetition bringing in another member of the team to amplify the sales pitch. The players soon had it down pat, and immediately wanted to know when they would get a chance to try it in a game. The answer was simple - during the biggest game of their lives ... live ... on ESPN.

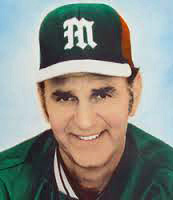

L-R: Ron Fraser, Skip Bertman, Gene Stephenson With the score tied 3-3 in the bottom of the sixth, Wichita's Phil Stephenson, younger brother of Gene, reached first on a walk. The first baseman was nothing less than the greatest base-stealer in college baseball history, with a single season record of eighty-six stolen bags in ninety-one attempts. When Miami pitcher Mike Kasprzak stepped off the rubber to check the runner, Stephenson dove back into the bag.

Kasprzak and first baseman Steve Lusby immediately looked to the dugout. They didn't say or signal anything. They didn't have to. Their faces said it all. C'mon, Coach ... this is the perfect time! The assistant coaches looked at Fraser, who nodded back with a look of "Oh, what the hell?" Skip Bertman looked back at his pitcher and signaled by sticking his finger in his ear. The Grand Illusion was officially in play. "The conditions had to be perfect and they were," Bertman recalled in the Rosenblatt press box twenty-six years later. "It was dusk, so the light was kind of tough. Stephenson was all riled up and ready to run, which we learned when he dove back into the bag when all we did was take a step off the rubber. And they had a player coaching first, not a coach. As soon as I signaled for it, the entire team stood up, even down in the bullpen. Everyone was in on it." Once again pitcher Mike Kasprzak stepped off the rubber, this time making a hand throwing motion toward first base. Once again Stephenson dove back and Steve Lusby dove over the runner, letting loose a curse word and taking off running for the right-field bullpen. Clearly, Kasprzak had overthrown the ball, right? Derailed and deflated from the play, the Shockers never recovered and lost the game 4-3. When the two teams met five days later for the championship game, Wichita was still complaining about what had happened and Miami won its long-sought first CWS title in a come-from-behind victory ... That summer, for the first time in its thirty-six year history, the College World Series led every sportscast in the nation, every talking head anxious to give his or her take on the Grand Illusion. The play placed The Blatt prominently on SportsCenter, This Week in Baseball, and Fraser's big-stage gamble immediately became a staple of every baseball coaching clinic from coast to coast.

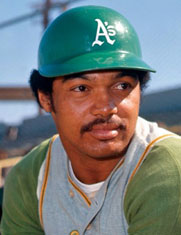

Life with Charlie O.

No More Mr. Nice Guy: The Life of Hardball, Dick Williams and Bill Plaschke

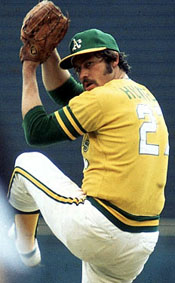

The 1972 Oakland Athletics got off to a sizzling start, winning 21 of their first 32. That excited owner Charlie O. Finley and posed a problem for manager Dick Williams. Charlie's daily phoning became even worse. He began using phones like they grew on trees, calling me more than twice a day. He began calling me so much that when we went on the road, I was forced to share an adjoining room with another club employee so that we could make arrangements for one of us to be in the room to answer the phone. Not that Charlie couldn't find me even if I'd disappeared. One off-day I was playing golf, about to putt on the eighth green, when a pro shop worker brought out a phone message. Guess who? I told the kid I'd call Charlie when I made the turn at the ninth hole. The kid said Charlie wouldn't wait, and gently begged me to get in his cart and drive with him to the phone. "Hey, Dick," Charlie belched when I picked up the phone, "how's the club?" "Which club do you mean?" I asked Charlie. "I'm standing here holding a bag full of them."    L-R: Charlie Finley and Dick Williams; Allan Lewis; Dick Green "Dick, I'm Allan Lewis, your new player," he said, sticking out his hand. "Allan," I exclaimed, "nice to meet you." I stood up, smiled, asked him to wait outside the office a second, closed the door behind him, and then picked up the phone. "Charlie!" I nearly shouted when the old man got on the phone. "Who in the hell is Allan Lewis?" Turns out he was our new pinch runner, a sprinter from Panama whose lack of baseball knowledge Charlie considered incidental. "Just call him 'The Panamanian Express.'" Charlie kept saying. I protested: "Charlie, we have no uniform for The Panamanian Express. No equipment. No locker." Charlie just laughed. Dick wait until you see this guy run," he said. And so we saw. A few days after he arrived, The Panamanian Express took off from first base on a long fly ball, head down, arms and legs pumping, great form. And if only the ball had fallen in for a base hit. But the ball was caught, as Lewis learned upon arriving at third base. What's a Panamanian Express to do? He shrugged and ran across the diamond, across the pitcher's mound, back to first. Playing in parts of six seasons, all for Charlie, Lewis appeared in just 156 games and batted exactly 29 times. But hey, the guy could run. And I shouldn't complain about just him. Charlie made 62 transactions that year, which has to be close to a record. All told, we put uniforms on 42 players. The worst part was that 12 of them played second base. Yes, Charlie didn't just try to influence my roster, he began trying to jimmy with my lineup, asking me to get a pinch hitter every time our second baseman batted. He figured that none of our second basemen could hit anyway, while all of them could field for a couple of innings. This was his rotating second baseman maneuver, Charlie's only in-game order that I felt compelled to carry out. After it cost us several wins by having the great-fielding Dick Green on the bench after three innings, and ultimately made a mockery of a playoff game, I finally ignored the order and prayed for my job. By then Charlie didn't notice, but only because he was too busy counting wins. Charlie's eccentricities were visible everywhere. In the spring of 1972 he decided to schedule us in an exhibition against a Japanese team in which a batter would strike out on two strikes and walk on three balls. So what if baseball had used different rules for 75 years? Charlie really thought this one would catch on, until our pitchers walked about 20 Japanese hitters and they beat the hell out of us. Call it an invention defeated by defeat. That spring he also decided to start fooling around with an orange baseball, which he actually used in an exhibition game in 1973. I'll never forget how former A's outfielder George Hendrick, who we'd just traded to Cleveland, hit three homers for the Indians with the orange ball but afterward almost single-handedly killed the idea by telling then-Commissioner Bowie Kuhn that he couldn't pick up the spin on the ball. I think he just did that to get back at Charlie. Call it an invention killed by a grudge. Charlie also acquired a fetish for mules. Don't ask me why. Ask the mule. I'm referring to Charlie's trademark, appropriately named Charlie O. In 1972, after letting him clomp around in the background of the organization for years, Charlie decided the fucking mule should join the team. He let him graze in the hospitality suites underneath the Coliseum during playoff games and even allowed him to lick the ice sculptures. He let him graze on the field throughout the left field foul territory. One problem. Before every game the mule had this habit, probably nerves, of taking a big crap down the left field line. It got so bad that I'd have to explain things to the opposing manager during our pregame meeting at home plate. "The mule shits out there, and we can't always be cleaning it," I'd tell him. "So if a ball rolls in the shit, it's still in play." Right about then the opposing manager would shit.    L-R: Catfish Hunter, Reggie Jackson, Rollie Fingers Then there was Charlie's most noticeable promotion, a gimmick so unusual that some of us have been reminded of it every morning in the mirror for nearly 20 years. Late in July 1972 we were on a charter flight from Boston, and the team, as usual, was pissed off about something. This time it was Charlie's rule about no facial hair. It wasn't that they disagreed with it but that one highly visible member of the team was ignoring it. Reggie [Jackson] had started growing a beard and mustache and refused to shave it, and the guys were mad that he seemed to be having so much fun. Catfish finally decided to address the issue in proper Oakland A's fashion. He decided to rat on him. Catfish walked to the front of the plane where Charlie was sitting. "Charlie," he announced, "Reggie Jackson has facial hair. Lots of facial hair. And we don't think it's fair." Finley looked at Catfish and then gazed into space. "Oh, really?" he said. By the time we landed in Chicago to drop Finley at his home, he'd concocted his solution. If facial hair had caused such a stir among the team, think what it would do for the fans. Not only didn't Finley reprimand Reggie, he offered $300 to anyone who would grow a mustache in the ensuing month and show it off at a promotion ingeniously called "Mustache Day." And so the Mustache Gang was born - a baseball team that came to look like a protest march. The players were so confused by Charlie's edict that most of them also decided to grow their hair long. We became one messy group of players, which only helped to cultivate our image as a free-wheeling team. But we weren't that free-wheeling. A month later, as soon as he gave us our checks for $300 following the successful Mustache Day, about half the team ran into the clubhouse to shave. he other half - well, some of us kept our mustaches for the rest of the season. And for the next season. And the next. To this day, as far as I know, several of those A's have never permanently shaved their mustaches. I'm one of them. You may have noticed another - a guy named Rollie Fingers. No, he didn't always own the most conspicuous mustache in sports. Like a lot of things with our team, his style started with Charlie. Dark Takes Over in Oakland When in Doubt, Fire the Manager: My Life and Times in Baseball,

Alvin Dark & John Underwood (1980) Alvin Dark became manager of the Oakland A's in 1974 after Dick Williams, who had led the A's to back-to-back World Series championships, left because of the meddling of owner Charlie Finley. Charlie Finley warned me he didn't want any of my "stupid fines." He said, "I don't want you to have any rules, I don't want any of those golf-ball fines. Just let the boys play baseball." I had always had fines - for missing curfews, for being late to meetings, for taking pills, for needing haircuts. I had a $1,000 fine for long hair, so I never had any trouble with hair. For the small stuff - a guy missing a cutoff, a missed sign - it might be two dozen golf balls. What made that embarrassing and therefore effective was that the balls went to the other players. ...

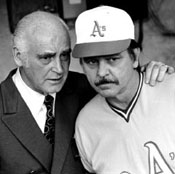

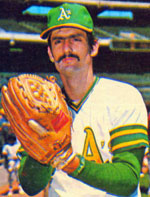

But Charlie said no fines, no rules, and then one day Reggie Jackson came late for practice. It got to be near eleven, and I began hearing little barbs. "What time does the Ten o'Clock Club start?" "Anybody here seen Reggie?"    L-R: Charlie Finley, Alvin Dark, Reggie Jackson When Reggie arrived I didn't say anything, and after the workout he came to my office and apologized. "Skip, I'm sorry. Fine me fifty dollars, let people know I didn't get away with anything."

Well, I couldn' fine him, but Reggie Jackson was one guy I wanted on my side. Like Sal Ban do and Catfish Hunter, he was a leader. I did not need him to be a poor leader. I said, "Reggie, don't worry about it. I know it was unintentional. I know it won't happen again. As far as I'm concerned you're a star everybody looks up to, so it's natural they would say things." "What? Did they say something?" I said, "Sure. Wouldn't you if Rudi or Bando had been late? Don't worry about it. But how about coming out tomorrow and taking some extra hitting?" Tomorrow was an off day. He said, "Okay. Sure." And he did, and the players knew it. By the end of spring training he was crushing the ball. Then, two days before we broke camp, we were scheduled to bus over to Tucson for our last spring game. I decided it was time to start living on a timetable - you have to when the season starts - so I said, "I want everybody on the bus at nine. Anybody who misses, it's two hundred and fifty dollars." Wash Your Mouth Out with Soap

You Can't Make This Up: Miracles, Memories, and the Perfect Marriage of Sports

and Television, Al Michaels with L. Jon Wertheim (2014) Al Michaels was in his second year as the Cincinnati Reds radio broadcaster with former Reds P Joe Nuxhall as his sidekick. There are bloopers, and then there are bloopers.

In May 1973, Joe Nuxhall and I bused with the Reds to Indianapolis, where we would play an exhibition game that night at the old Bush Stadium against our Triple-A affiliate, the Indianapolis Indians. ... Per usual, I taped my pregame show, The Main Spark, with [manager] Sparky Anderson in his clubhouse office. Our standard procedure was for me to tape the Sparky show with a cassette recorder, and then hand the recorder to Joe, who would tape his pregame show, called Turfside, in one of the dugouts with a player. We had a regular engineer who worked every game at Riverfront, and on the road there were regular engineers who worked with different teams, and were experienced in dealing with different formats and workflows.

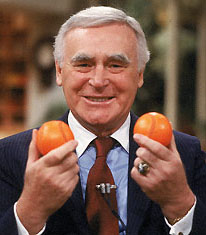

Al Michaels and Joe Nuxhall in Reds broadcasting booth So, that night, Joe taped his Turfside show with one of our minor-league prospects in the Indians dugout. I was out by the batting cage and as he taped his segment maybe ninety minutes before the game, I noticed several of the Reds' players gathered in front of the Indians dugout. There was a little commotion, and a lot of laughter. I thought nothing of it - but as I look back now, I remember one of the players tossing pebbles in Joe's direction to distract him.

I took the tape machine back from Joe, went back upstairs to the broadcast booth about an hour later, and gave it to the engineer, whom we'd never worked with before - he was on loan from a local station in Indianapolis. I told him each of our segments began on tape the same way - with Joe or I saying "Five, four, three, two, one" as a cue to let him know he could then hit playback. Then I went out on a carwalk to get the last rays of the afternoon sun. I had in my hand a transistor radio to listen to the show and make sure everything went smoothly. Indianapolis is barely one hundred miles from Cincinnati and our station, WLW, came in clear as a bell. I listened to The Main Spark, and everything sounded fine. But when Joe's pregame show came on, this is what I heard out of my transistor radio: "Hi everybody, this is Joe Nuxhall. The Reds are in Indianapolis tonight playing their Triple A - get our of here, get out of here - you son of a bitch, you cocksucker ... Five, four, three, two, one. Hi everybody, this is Joe Nuxhall ..." I looked down at my radio as if it were a hand grenade that had been tossed into a crowd. Joe had forgotten to erase the original recording before starting over. I thought and hoped I was dreaming. Now Joe comes bounding up the stairs to the broadcast booth, and as he sits down, I have to break the news, "Joe, we've got a big problem." I explained what had happened. Joe turned bedsheet white. Remember, Joe had started his career pitching for the Reds in 1944 when he was fifteen years old. Now he was sure he was going to get fired. On the broadcast that followed that night, he might as well have been catatonic. We bused back to Cincinnati after the game. The players, who'd all heard about it from their wives, were in hysterics - but poor Joe looked as if he was ready for his own memorial service. Back home the next morning, we both got calls from Dick Wagner [an assistant to the GM]. ... Wagner wanted us both in his office in midafternoon. Nuxie was preparing for the worst. When we entered Wagner's office together, Dick had a very stern look on his face, but he also had a slightly perverse sense of humor, and I could sense that deep down, he understood the other side of this. But at this juncture, this was not exactly a laughing matter. "Tonight," he told Nuxhall, "when you go on the air, you're going to apologize." At this point, it was clear that Joe was not going to be fired - and he was relieved beyond comprehension. That morning, a local newspaper columnist had written, "How about that Reds broadcast team? Al Michaels does the play-by-play. Joe Nuxhall handles the off-color." We left Wagner's office and started getting ready for the broadcast. Nuxie went about his regular pregame routine. The players were still ribbing him, but he was in decent spirits - he'd avoided death row. Still to come, though, was the on-air apology that Wagner had demanded. And when Joe got up to the broadcast booth, about twenty-five minutes before he game, I could tell he was extremely nervous - in fact, he was sweating profusely. I looked over at him and asked what was wrong. With the clock ticking down, he explained, "I have to deliver this apology. I don't have any idea what to say." I tried to get Joe to relax. I wanted to lighten the mood, so I said, "Look, Joe, it's simple. Just say, 'Ladies and gentlemen, I'm very sorry I said 'cocksucker.' And it won't happen again." My attempt at humor was an abject failure. I thought Joe was ready to pop me. But then I was able to get him calmed down, and help him work out what to say. He got through it, and we moved on. And he'd keep his job with the Reds another three decades, until 2004 - sixty years after his pitching debut. "Baseball and Beer Both Begin with 'B.'"

The Road to Omaha: Hits, Hopes, and History at the College World Series,

Ryan McGee (2010) In the dark dawn hours of Saturday, June 9, 2000, Jeff Hyde and Stan Evans had no idea where they were going or what they were doing. They just knew they wanted to go to Rosenblatt Stadium.

Five days earlier, their beloved Louisiana-Lafayette Ragin' Cajuns were inexplicably one game away from earning their first invitation to the College World Series, pitted against the hard-hitting South Carolina Gamecocks in Columbia, South Carolina. They had a freshman pitcher on the mound and on the road against the number-one team in the nation. Evans made Hyde promise that if the Cajuns won, they would drive from Lafayette to Nebraska to root them on. "Sure," the oil-field worker said as he agreed to the proposal, "but it'll never happen." The Cajuns beat the Cocks 3-2. Thursday night after work Evans was sitting in Hyde's driveway leaning on the horn of his wife's Toyota Camry, packed with little more than some maps, a duffel bag, and one small cooler. Without tickets, a hotel room, or a single friend west of Texas, they hit the road, arriving at The Blatt on game morning to watch 2000's version of The Underdog. The Cajuns bleached their hair in an act of unity and upset Clemson to reach the semifinals, coming to within one game of facing in-state nemesis LSU for the championship.  Rick Haydel scores winning run for ULL against Clemson. "It didn't matter that they lost," Hyde remember while standing over a boiling pot of some sort of alien-looking, yet delicious-smelling crustaceans. "We were hooked." CWS Tailgating Like Evans and Hyde, Samstad was serious about his tailgating. Very serious. Hanging from the trees as traffic crawled by was a giant white banner, decorated with a stylish green alligator, a bright red baseball, and the unavoidable lettering that read, CWS TAILGATERS. As Samstad cooked up bacon and eggs for a couple of dozen friends and a few nameless strangers drawn to the scene, he sipped a 10:00 A.M. Newcastle, and handed over a business card with the 'Gator logo (which is trademarked) and the address of his soon-to-be-launched Web site ... Told you he was serious.

LSU tailgaters in Omaha The decor of alligators was outshone only by the endless number of pink flamingos. They hung from trees. A FLAMINGO CROSSING sign dangled from a street post. One woman wore a hat fashioned after a flamingo's head. And lined along the road were eight plastic flamingos, each bearing the logo of a CWS team. One of the birds sat a few feet away from the other seven, separated from the flock with a black cloth bag tied over its head and a handful of dead flowers at its feet. "That's Florida State," Samstad said, pointing to the tiny black-and-white Seminole insignia taped to its back. "They're gone, so that bird is dead." Thirty minutes after a team was eliminated, the CWS Tailgaters gathered around the birds for the "Hooding Ceremony," when Samstad would say a few words about the deceased, place the flowers on the ground, pour a beer over the bird's head, and tie on the hood. "It's surprisingly emotional," explained Bill Nash, a Chicago resident with a Rollie Fingers mustache who, along with wife Diana, had parked alongside Samstad for nine years. "Then again, after a dozen beers about anything will make you cry, won't it?" |