|

Ed Doheny: The Paranoid Pirate

Michael Lynch, Baseball's Untold History: The World Series (2016)

Ed Doheny After starting the season 12-6 that year, he began exhibiting odd behavior and believed he was being followed by detectives, prompting him to leave the team and head home to Massachusetts to rest, and causing newspapers to call him “deranged.” Friends and family assumed he was just tired and nervous about pitching in the big leagues, so they paid no attention to his behavior. He rejoined the team after a few weeks and continued to win, but made his last start on September 7 before going home for more rest. Pirates manager Fred Clarke had been in contact with Doheny’s physician, who told him Doheny “couldn’t be depended upon” for the World Series. “Of course we sometime ago gave up all expectation of Doheny’s helping us in the present series,” Clarke told reporters, “but I had hoped he would be all right for next season.” Despite being under the daily care of Dr. E.C. Conroy, Doheny’s condition worsened until he finally snapped. Conroy checked in on Doheny on October 10, but was told his services were no longer needed. Conroy tried to coax Doheny into continuing his treatment, but the pitcher ordered the doctor to leave his house. When Conroy failed to comply, Doheny hit him in the face and escorted him to the sidewalk. Police were called but it was decided that he just needed rest, so another doctor and nurse were called in to help him calm down, which they did. The next morning Doheny became violent. While his nurse, Oberlin Howarth, had his back turned Doheny struck him on the head repeatedly with a cast-iron stove leg he’d concealed in his bed. The blows opened a large gash on Howarth’s head and knocked him unconscious. Neighbors rushed to Howarth’s aid only to find Doheny at his front door wielding the bloody stove leg and threatening anyone who came near him. After a one-hour stand-off with neighbors and police, Doheny was taken into custody and committed to the Danvers Lunatic Asylum. Sadly, the hurler deteriorated to the point where he no longer recognized family and friends, including his own wife. He spent the last 13 years of his life in asylums before he died on December 29, 1916 at the Medfield State Asylum in Massachusetts. He’s buried in his home state of Vermont.

Sale of the Century

Bill Francis, Memories and Dreams: Official Publication of the Baseball Hall of Fame (Winter 2019)

100 years later, Yankees' purchase of Babe Ruth's contract is still being felt throughout the baseball world.

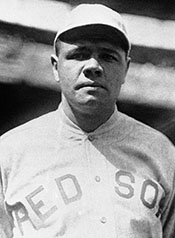

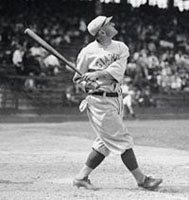

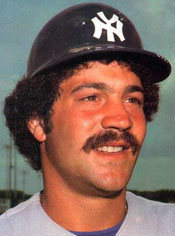

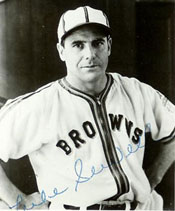

For fans of the Boston Red Sox, the unthinkable, unimaginable, unfathomable happened 100 years ago with the sale of Babe Ruth to the Yankees. Ruth, all of 24 years old, had made the transition from str southpaw pitcher to the premier slugger in the game by 1919. Now patrolling LF for Boston, and thanks to his powerful left-handed stroke, he clubbed 29 HRs that set a new single-season big league record. But then the news broke. Ruth would soon be playing 77 games each season at the Polo Grounds - his new home ballpark until Yankee Stadium opened in 1923 - with its short RF fence. It was announced on Jan. 5, 1920 - though the transaction had been consummated a week earlier - that Ruth was now a member of a rival American League franchise. Newspapers across the country shared the news with provocative headlines: "Red Sox Sell Ruth for $100,000 Cash" read The Boston Globe; "Ruth Bought by New York Americans for $125,000, Highest Price in Baseball Annals" blared The New York Times; "New York Yankees Buy Babe Ruth from Boston Red Sox" stated the Chicago Tribune. "Like all things Ruthian, everything about Ruth's sale from the Red Sox to the Yankees was outsized," said Tom Shieber of the National Baseball Hall of Fame staff. "The price tag was unparalleled in sports history, the story was obsessively covered in the press and every last detail was voraciously consumed by baseball fans nationwide. With the possible exception of the Louisiana Purchase, what other acquisition has reached the same level of long-term recognition in the American public's conscience?" So how did it come to this, that Ruth, a legend in his own time, was shipped out of Boston just as his offensive prowess was emerging? Coming off a 1919 season in which he led the Junior Circuit not only in homers but also with his 113 RBI and 103 runs scored, the Colossus of Clout wanted a new contract that would pay him $20,000 per season. Prior to the 1919 season, Ruth had signed a three-year deal with the Red Sox that would pay him $10,000 annually. "You can say for me," said Ruth to The Boston Globe on Oct. 24, 1919 ... "that I will not play with the Red Sox unless I get $20,000. You may think that sounds like a pipedream, but it is the truth. I feel that I made a bad move last year when I signed a three-year contract to play for $30,000. The Boston club realized much on my value, and I think that I am entitled to twice as much as my contract calls for."     L-R: Babe Ruth, Harry Frazee, Jacob Ruppert, Miller Huggins L-R: Babe Ruth, Harry Frazee, Jacob Ruppert, Miller Huggins"The price was something enormous, but I do not care to name the figures. It was an amount the club could not afford to refuse," said Frazee ... I should have preferred to have taken players in exchange for Ruth, but no club could have given me the equivalent in men without wrecking itself, and so the deal had to be made on a cash basis. No other club could afford to give the amount the Yankees have paid for him, and I do not mind saying I think they are taking a gamble. With the money, the Boston club can now go into the market and buy other players and have a stronger and better team in all respects than we would have had if Ruth had remained with us. "I do not wish to detract one iota from Ruth's ability as a ballplayer nor from his value as an attraction, but there is no getting away from the fact that despite his 29 HRs, the Red Sox finished sixth in the race last season," Frazee added. ... "I am not at liberty to tell the price we paid," smiled Yankees co-owner Jacob Ruppert ... "I can say positively, however, that it is by far the biggest price ever paid for a ballplayer. Ruth was considered a champion of all champions, and, as such, deserving of an opportunity to shine before the sport lovers of the greatest metropolis in the world." Then, in a bit of foreshadowing, Ruppert added, "It is not only our intention, but a strong life purpose, moreover, to give the loyal American League fans of greater New York an opportunity to root for our team in a world's series. We are going to give them a pennant winner, no matter what the cost. ... Yet the fans can rest assured we by no means intend to stop there. Eventually we are going to have the bes team that has ever been seen anywhere." Ruth, contacted in Los Angeles - where Yankees manager Miller Huggins helped secure a contract that would pay the HR king $20,000 per season in 1920 and '21 - claimed not to be surprised by his sale to New York, noting: "When I made my demand on the Red Sox for $20,000 a year, I had an idea they would choose to sell me rather than pay the increase, and I knew the Yankees were the most probable purchasers in that event." ... While the official sale price of Ruth was not made public at the time of the transaction, numbers were speculated about. According to modern research compiled by Michael Haupert, professor of economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, the actual purchase price was $100,000, payable in four annual installments of $25,000 at 6% interest, with New York making the first payment on Dec. 19, 1919. ... When Casey Ran the Bases

Great Moments in Baseball: From the World Series of 1903 to the Modern Records of Nolan Ryan.

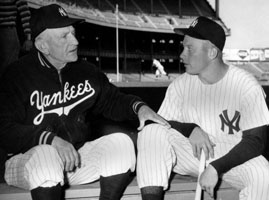

Tom Seaver with Marty Appel (1992) The first time Mickey Mantle ever played in Ebbets Field - it was during the 1952 World Series - his manager, Casey Stengel, walked him to the outfield and showed him how the ball might carom off the walls.

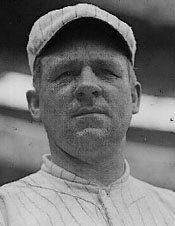

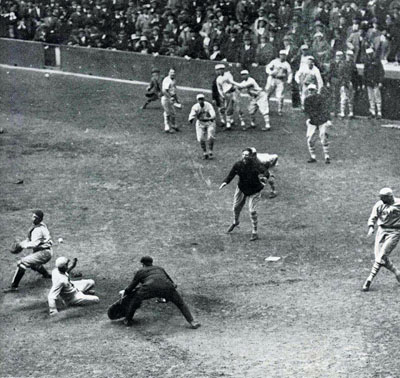

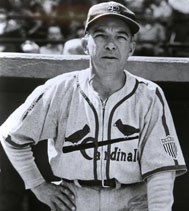

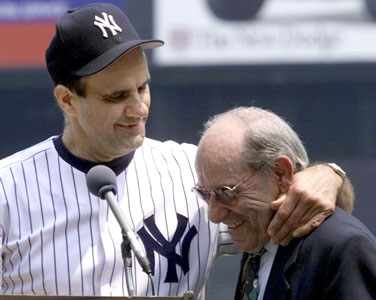

Mantle looked at him as if he were crazy. He viewed Stengel as a very old man who might be capable of making up a lineup but who would never in a million years know how to play balls bouncing off outfield walls. Stengel later told people that he said to Mantle, "You think I was born this old?" And he proceeded to take a few minutes to explain to his young prodigy that he had, in fact, played those walls in that very park a few hundred years earlier. He had been a Dodger outfielder, right there in Ebbets Field, from 1912 to 1917, and had played in the 1916 World Series there. ... The funny thing about Mantle's reaction in 1952 to the 62- or 64-year-old Stengel (no one was sure how old he really was) is that Casey was considered an "old man" as far back as the first World Series ever played in Yankee Stadium, in 1923. This was so in part because, at 33 (or 35), Casey was among the oldest Giants ... in part because, well, he looked older than he was. He had this wrinkled face and these bowlegs. And, although he was not a coach, he was sort of a pal to John McGraw, the manager, looked older than McGraw (who was fifty), and was a platoon player, which was still unusual in those days. (Only Casey Stengel could be responsible for a story that has both John McGraw and Tug McGraw in it.) Stengel later made platoon baseball, the tailoring of a lineup to respond to whether the opposing pitcher was a lefty or a righty, a part of the modern game. One can plainly see where he learned it. In 1922 and 1923, his only two full years under McGraw, he played in 150 games and batted .355, with 12 homers, 87 runs batted in, and 10 stolen bases. They were the most productive two years of his fourteen-year playing career, and he got into the World Series both times. It's easy to understand how he would react when future players complained about platooning. The 1923 World Series offered the third consecutive matchup between the Yankees and the Giants, with the Giants seeking to become the first team to win three straight world championships. The year 1923 was different because the Yankees would play their home games not at the Polo Grounds, where they had been tenants since 1913, but in the new Yankee Stadium. It had been hastily constructed prior to the season just across the Harlem River from the Polo Grounds on an old Bronx lumberyard turned park. ...    L-R: Casey Stengel and Mickey Mantle 1952, Casey Stengel as a Giant, John McGraw The first game, on October 10, drew an attendance of 55,307 at Yankee Stadium, almost 20,000 fewer than had attended the team's opener in April. Miller Huggins, the Yankees manager, had a former Giant right-hander on the mound, Waite Hoyt, so McGraw had Stengel, a left-handed hitter, in CF, batting sixth. The Yankee fans no doubt expected Ruth to hit the first World Series home run in the new stadium, just as he had hit the first one in the regular season. The Yanks jumped off to a 3-0 lead after two innings, driving Giant starter Mule Watson out of the game. The big hit for the Yanks was a two-run single in the second by CF Whitey Witt, the team's leadoff hitter. But then the Giants knocked out Hoyt in the third as they scored four times, the big hit a two-run triple by Heinie Groh with his odd-shaped "bottle bat." Bullet Joe Bush, one of the many ex-Red Sox players who had been sold to New York, came in for the Yanks. The game continued 4-3 Giants until the Yanks tied it in the seventh on a single by Bush and triple to right by Joe Dugan. Ruth, the next batter, grounded to first, where George Kelly made a terrific play and fired home to nail Dugan and keep the score 4-4. Neither team scored in the eighth. In the ninth the Giants had Ross Youngs, Irish Meusel, and Stengel due to hit against Bush. Youngs lined out to Witt in center for the first out. Meusel grounded to Dugan at third for the second out. Up came Stengel, who had flied deep to Ruth in right, walked, and singled, the single being the only hit off Bush since he'd come on in the third. Bush delivered, and Casey smacked it on a line into LCF. Witt from center and Bob Meusel (Irish's brother) from left raced for the ball, but it was soon beyond them, heading for a fence that was 460' away. Pushing his old body as hard as he could. Casey proceeded around the bases. It looked as though he had almost run out of gas near third but, in fact, one of his shoes had come loose and was only half on his foot. Witt picked up the ball and fired it to Meusel. Now it was the relay home as Casey gave it everything he had. Wally Schang, the Yankee C, waited for the throw, which was just a moment late as Casey slid for the plate in a cloud of dust. He got up slowly, dusted himself off, smiled, and walked to the Giants' dugout, to the cheers and laughter of his teammates. The man who would go on to earn Hall of Fame honors by leading his Yankees to ten pennants in twelve years as manager had hit the first World Series home run ever in Yankee Stadium. It was an inside-the-park homer and it gave the Giants a 5-4 win.  Stengel slides for inside-the-park HR in 1923 World Series It was Game Three, two days later, a scoreless tie in the seventh inning. Sad Sam Jones was on the mound for the Yankees with one out in the seventh when Casey Stengel blasted one into the RF bleachers. The Giants hung on to win that game 1-0, giving Stengel his second game-winning hit of the Series and the Giants a 2-1 lead in games. But the Yankees went on to win their first World Championship, no thanks to the .417 hitting and two game-winning homers by their future manager. Had they given sports cars to series MVPs back then, Casey might have driven off with a handsome roadster. Those who only know of the wrinkled old face, so full of character, that belonged to Casey Stengel, Manager, will find his exploits as a playe rsimply "amazin'," one of the favorite words of "the Ol' Perfessor." Full House

Tim Wiles, 2004 World Series Program

Satchel Wasn't Pleased Larry Tye, Stachell: The Life and Times of an American Legend (2009)

Jackie's Rookie Season

Claire Smith, Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the Hall of Fame, Winter 1019

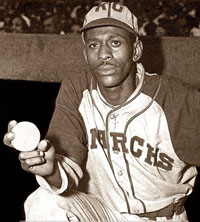

Alfred Surratt would never tell where, along the way, he was dubbed "Slick." It was a Kansas City Monarchs thing, a Negro Leagues thing, a baseball thing. Brothers to the core, the men of the Monarchs kept one another's confidences, watched one another's backs, mourned teammates' losses and failed dreams, and cheered on their brothers' achievements. Never were the cheers louder, said Slick Surratt, than on April 11, 1947, the day Branch Rickey and the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson, a one-time Monarch, to a major league contract. ... The joy within the black baseball community was palpable. The destruction of segregation within Major League Baseball was at hand. Four days later, on April 15, 1947, Robinson would debut with the Dodgers, his first step onto Ebbets Field in Brooklyn tromping out the National Pasttime's odious color barrier forever. As we all now know, it wasn't just singing on to be a baseball player. Those opposed to integration would push back, virulently, viciously, unrelentingly. Robinson, a former Army officer and one of the greatest ahtletes to come out of UCLA, was about to meet his great opponent: Jim Crow. And he would be asked to do so pretty much on his own. One black man against a nation in which large swaths were steeped in segregationist policies. Raised in California, Robinson and his bride would be asked to step into hostile territory where racism ws not only codified by gentlemen's agreements, but mandated by law. The ugly cultural divide they were about to experience was not only enforced by men wearing badges, but also by nightriders hidden beneath hoods and wearing sheets. The Dodgers and Robinson, daring to change in 1947 what legislatures, Congress and presidents had failed to do ..., knew both the risks and the responsibilities. Yet the man who carried the hopes of so many Slick Surratts, Hank Aarons, and Willie Mayses, never shirked. Incredibly, Robinson not only authored one of the most impressive inaugural seasons the game had ever seen, he also gave lessons in heroism each and every day he stepped onto a major league field. For the record, the first time Robinson stepped on such a field was on that April 15 in 1947; the 28-year-old debuted against the Boston Braves before more than 25,000 fans at Ebbets Field. He played first base and went 0-for-3 at the plate. 155 games later, Robinson had authored the first chapter of what was destined to be a Hall of Fame career. Likely no other player ever traveled quite so treacherous a path to the Hall as did Robinson. In an article printed in The New York Times on May 10, 1947, it was revealed that Robinson had received "threatening letters of anonymous origin" from the day he'd broken into the big leagues that spring. ... "This disclosure followed on the heels of a report that a strike of opposing players against the Negro players had been spiked." "Harassment of Robinson ... by unidentified persons was confirmed in Philadelphia last night by Branch Rickey, president of the Brooklyn Baseball Club. 'At least two letters of a nature that I felt called for investigation were received by Robinson,' Rickey said. "Robinson himself admitted receiving several such letters. ... A high police official here disclosed that a letter warning Robinson to 'get out of baseball' had been turned over to the police department by the baseball club for investigation."   L-R: Branch Rickey, Jackie Robinson and Ben Chapman The indignities heaped on Robinson by others in baseball uniforms included spikes-high slides and head-high knockdown pitches. Racist epithets were the rule of the day. What historians came to understand was that Robinson would not, could not, lash out, because he, too, had made a gentleman's agreement with Rickey. In his words, ... Robinson said, "I remember Mr. Rickey saying to me that I couldn't fight back, and I wondered whether or not I was going to be able to do this." Nowhere was his resolve to honor his agreement with Rickey tested more than in Robinson's first games played against the Phillies in late April at Ebbets Field. The Phillies, led by manager Ben Chapman, infamously rained an unending torrent of racist slurs on Robinson, taunting the infielder about his physical features, telling him to go back to the cotton fields and calling him the "N" word. The onslaught was so relentless and debilitating that Robinson later said it pushed him closer to breaking than any other humiliation suffered that season. "For one wild and rage-crazed minute, I thought, 'To hell with Mr. Rickey's noble experiment,'" Robinson once recalled. He was physically and verbally abused, particularly when he was on the road, in certain cities," said Rachel Robinson, Jackie's wife, in ... 1998. "The taunts angered him, sometimes frightened him, but he turned away from them." Said Robinson's teammate, CF Duke Snider: "He knew he had to do well. He knew that the future of blacks in baseball depended on it. The pressure was enormous, overwhelming and unbearable at times. I don't know how he held up. I know I never could have." Author Jonathan Eig wrote of Robinson's brutal season in his book Opening Day. In a 2016 interview ..., Eig said the incidents with Chapman brought into focus what Robinson was being made to endure. "It was so offensive that, for a lot of Americans, it was a wake-up call," said Eig. "It made people, white people in particular, realize for the first time just what burden Robinson was shouldering." As sportswriter Jimmy Cannon wrote: "Jackie Robinson is the loneliest man I have ever seen in sports." Chapman would later try to explain away his actions by saying that he was bench-jockeying, and, in an effort to say he wasn't being racist, described how he also hurled ethnic slurs at Italian-American players such as Joe DiMaggio and Jewish players like Hank Greenberg. Chapman told writer Allen Barra he was doing no less with Robinson, looking for a way to rattle a rookie. ... What Chapman could not envision was that his action eventually won Robinson sympathetic - and vocal - allies. As Eig wrote in Opening Day, in the second game of the initial Phillies-Dodgers series, the Dodgers' Eddie Stanky, a veteran infielder and native Philadelphian, called out Chapman and the Phillies, deeming them cowards for railing against a man who could not fight back. "It was the first time a lot of white people and white reporters in particular noticed the abuse Robinson was taking," Eig said, adding, "I interviewed a fan who had been a teenager who went to one of those games, heard the heckling, and was shocked." By the time the Dodgers visited Philadelphia in May, Chapman, prodded by baseball, asked to have his picture taken with Robinson. The Dodgers rookie would not shake his hand, so the two men grasped opposite ends of a baseball bat as photographers snapped away. Off the field, many municipalities remained stubbornly unwelcoming. Even after Chapman's attempted truce, the Dodgers were not allowed to register at their chosen hotel in Philadelphis until other accommodations were made for Robinson. Sadly, this was nothing Robinson and the Dodgers had not experienced before. Save for the Spring Trainings spent with the Dodgers in the Caribbean rather than segregated Florida and a minor league season spent in a welcoming Montreal, Robinson felt the hot breath of hate at every step even as he broke color barriers one ballpark, one town, one city at a time - with "Colored Only/White only" signs on water fountains and public bathrooms throughout the south and meals delivered through restaurants' back doors and eaten in solitude on the back of buses. "He faced it in Spring Training, in every town in Florida that he visited. He faced it in Pittsburgh and St. Louis and Cincinnati," Eig said. "I doubt that he would've singled out Philadelphia as the worst place in the world." Larry Doby, who became the second black major leaguer in the modern era when he joined the Cleveland Indians midseason in 1947, was often asked by youngsters of later generations why Robinson, he and others didn't just refuse to leave balking hotels, movie theaters and restaurants. "Because we didn't want to die," Doby told one such inquisitor ... Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. told Don Newcombe, Robinson's Dodgers teammate ... "You'll never know how easy you and Jackie and Doby and Campy (Roy Campanella) made it for me to do my job by what you did on the baseball field." Thus, 72 years after 1947, we still marvel at a rookie who - by any measure - refused to fail. Robinson, buffeted by societal ills, but steeled by the challenge to change a nation, hit .297 in 151 games that season. He stole 29 bases, more than anyone else in the National League, scored 125 runs and ... helped Brooklyn win a National League pennant for only the second time since 1920. It would be the first of six league championships won by a Brooklyn team that featured a player Dr. King called "one of the truly great men of our nation." For his efforts, as well as for the example he set, Robinson received the first-ever Rookie of the Year Award by the Baseball Writers' Association of America, an award that now bears his name. In the words of Yogi Berra, some might say that Jackie Robinson made that award necessary. Still a Unique Feat

"Where Are They Now? Tony Cloninger," by Thom Henninger

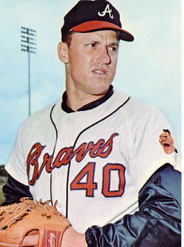

Baseball Digest July/August 2016 Tony Cloninger, who spent 12 seasons in the major leagues, lives barely a stone's throw from his North Carolina high school, just north of Charlotte, where six decades earlier his baseball career took shape. He was a catcher then, but his ability to throw a mid-to-high-90s fastball landed him on the mound.

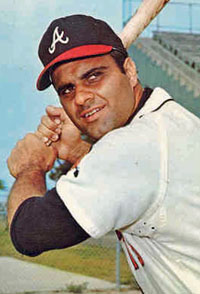

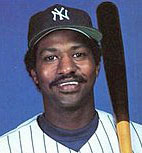

The 6-foot right-hander went on to win 24 games for Milwaukee Braves in 1965, but after all these years, he's remembered most for being one of 13 major leaguers to hit two grand slams in a single game. Cloninger, the only pitcher to slug two slams in a game, enjoyed his milestone moment 50 years ago in 1966, during the Braves' first year in Atlanta. By then he had spent five seasons with the franchise, with a locker located between future Hall of Famers Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews in the Braves clubhouse. "That always puts a smile on my face and tears in my eyes when I think about how good those guys were to me when I got to the big leagues," Cloninger recalls ... "Talking to me, and listening to them talking about how they approached different pitchers. And they would comment on how I had pitched and helped me along the way." ... On July 3, 1966, Cloninger took the hill as the 35-45 Braves closed out a weekend set at Candlestick Park against the first-place San Francisco Giants. Before Cloninger faced the likes of Willie Mays, Willie McCovey and Jim Ray Hart, the Braves chased Giants starter Joe Gibbon by rallying for seven first-inning runs. After Atlanta jumped in front on Joe Torre's three-run blast over the 410-foot sign in center field, Cloninger came to the plate to face reliever Bob Priddy with the bases loaded and two outs. He worked a full count before pounding a Priddy fastball to nearly the same spot as Torre's homer. "I was just trying to hit the ball hard up the middle and I hit a line drive out to straightaway center field," says Cloninger, who used a heavy, 35-inch bat made for his friend and roommate, Braves infielder Denis Menke. "I just put my number on it," Cloninger chuckles. "He always gave me a certain number of bats."    L-R: Tony Cloninger, Joe Torre, Denis Menke With the Braves up 9-0 in the fourth, Cloninger took the same bat to the plate, once again after Menke had drawn a two-out walk to load the bases. This time Cloninger faced lefty Ray Sadecki, the former 20-game winner who had come to the Giants in a recent trade ... The right-handed-hitting Cloninger went the other way, driving a Sadecki fastball into the right-field seats.

Cloninger became the first N.L. player to ever stroke two slams in a game, and his eight RBI established a new single-game mark for a pitcher. In the eighth, he singled off Sadecki to drive in his ninth run, which remains the single-game record. Today Menke's bat is part of the Hall of Fame collection. The North Carolina native says he flirted with a 10th RBI in the 17-3 victory. In his sixth-inning at-bat against Sadecki, Cloninger turned on a pitch and hit it to left as hard as his two homers. "The wind was blowing in from left field real heavy," Cloninger says. "The others were line drives. I got under this one some, and it was up there a ways. Len Gabrielson went up to the left-field fence and pulled it in." Sadecki gained a bit of revenge with a home run of his own off Cloninger, a fifth-inning solo shot that became a source of ribbing by teammates. "We got a lot of kidding about that," Cloninger says and laughs. "They said, 'He let you hit one and you let him hit one.' I said, 'No, he's always been a good hitter.' ..." Cloninger hadn't done much as a hitter until 1966. He had batted .174 with a lone home run during his first five seasons with the Braves, but showed signs of a budding power surge on June 16, 1966, roughly two weeks prior to his two-slam game. He popped two home runs in a 17-1 win over the Mets, turning on a pitch for a three-run homer off Dave Eilers and going the other way for a two-run shot off Larry Bearnarth. Beginning that day, through the end of the 1966 season, Cloninger batted .282 and slugged .526, with five homers and 23 RBI in just 82 plate appearances. His hitting spurred more at-bats. "It was hard to believe, but for the rest of my career, I pinch-hit some," says Cloninger. "I was a fastball hitter, but if a guy made a mistake with a breaking ball, I could hit that," he adds, "because sitting beside those two guys, I learned a little about hitting. It wasn't just how hard you could swing, but to hit the ball out front." Those two guys, of course, were Aaron and Mathews. "What a gentleman and dear friend. I would have cherished him if he couldn't hit a baseball," Cloninger says of Aaron. ... A Bizarre Year - 1

George: The Poor Little Rich Boy Who Built the Yankee Empire, Pete Golenbock (2009)

The year 1971 was a bizarre one, even for George Steinbrenner. It began with the Case of the Red Lips, and it ended with Steinbrenner's imaginary KO of two men in an elevator in Los Angeles and an apology to the city of New York and to Yankee fans everywhere. In between he threatened to sue Billy Martin if he didn't take out several allegation in his book, Number 1, screwed around with the roster in order to take publicity away from the crosstown Mets, and tortured manager Gene Michael before firing him and bringing back Bob Lemon. He also humiliated Reggie Jackson for having the audacity to be in a batting slump. This was the year the reporters began referring to George as "Mr. L. Toons" (the L, of course, stood for Looney). It was also a year to remember, in part because the strike-shortened season allowed the Yankees to sneak into the World Series.

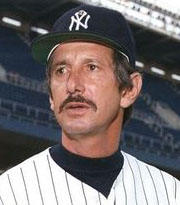

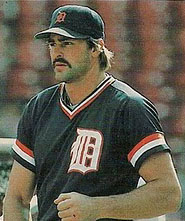

The Case of the Red Lips jeopardized the job of public relations head Larry Wahl. The theme of the yearbook was the Big Apple, and on each player page the designer placed a red apple with the player's number inside. The printer wanted to make sure the red color was the same throughout the book, and he focused on the apples, not the other pictures. George had chosen a black-and-white photo of himself that had been colorized, and when the yearbook was printed, his lips were a tad more red than normal. At first, George was satisfied with the way it came out until a secretary said to him, "Oh, it looks like you have lipstick on." Said an employee who was there, "That's how it usually goes with George. Someone will push a button and send him over the edge." When George heard the criticism, he freaked. He bellowed that the photo made him look like he was wearing lipstick, and he ordered all ten thousand copies destroyed. When ESPN reporter Keith Olbermann took the story national, George blew up at Wahl again. The genial Wahl, who was newly married, resigned in June and took a better-paying job at ABC. After Billy Martin punched out the marshmallow salesman and was fired, he had time to sit down and work with me on his autobiography, which was titled Number 1. I would travel to his home two or three times a week, or we would go to a restaurant or a bar, where he would drink club soda and lime. After losing his job, I guess he figured it was a good idea to stop drinking, and he abstained the whole eight months we worked together. Before the book came out, it was excerpted in the Daily News, which bulleted the five things their editors found most interesting/outrageous. Right around publication in the spring, Billy and I both got letters from Steinbrenner insisting that the five bulleted items be taken out of the book. Among those items were the tugboat incident and Billy's charge that George had his phones in the stadium tapped. Billy insisted that what he had said was true and initially refused to back down. Once the book was published, it quickly hit the New York Times best-seller list, racing to number five. It was on the Times list for fifteen weeks. George then put pressure on Billy to take out those bulleted items, knowing that if Billy did his credibility would be questioned and book sales would drop precipitously. Which is exactly what happened. We sold 110,000 copies before it was announced in the Daily News that Billy was taking out the bulleted items in the next edition of the book. ...    L-R: Reggie Jackson and George Steinbrenner, Billy Martin, Gene Michael The Mets beat the Yankees that day on two long home runs. Rookie pitcher Mike Griffin gave up five runs to lose it. Steinbrenner's anger was monumental. Reporters couldn't wait to hear what he had to say. He didn't disappoint. He blasted catcher Rick Cerone for striking out with the bases loaded, making a throwing error, and calling the two pitches the Mets hit for homers. He blasted other Yankee players as well. He finished by saying, "The team was embarrassing. Now's the time to screw down the hatches. I want to see some improvement." Then he said, "And Mike Griffin won't be pitching for us any longer,." It was not an idle boast. Griffin was sent to Columbus and traded to the Chicago Cubs a few weeks later. Oh, did Steinbrenner resent the Mets, who had a rookie making headlines by the name of Tim Leary. What caught the eye of the newspapermen was the skill of this kid, who had pitched only in Class A ball the year before. Steinbrenner became insanely jealous when the Mets stole headlines from him, and so to compete with the Mets for the back-page headline, he picked a twenty-year-old pitcher by the name of Gene Nelson, with a 20-3 record in Class A Fort Lauderdale the year before, to be the Yankees' answer to Tim Leary. When George put Nelson on the roster, another pitcher had to go, and so he sent down 22-year-old Dave Righetti, a young player who had pitched well enough to make the team and deserved to be there. Steinbrenner got his headlines. He talked about how Nelson was a real-life Frank Merriwell story. "People will come and see him pitch," he said. "He'll put fans in the stands." But this was just wishful thinking on Steinbrenner's part. Nelson wasn't ready, and while Righetti was wasting away at Columbus, he compiled a 5-0 record. When he returned, he won his first three starts, helping the Yankees to the lead when the players went on a seven-week strike that began on June 12, 1981. The players set the strike deadline for June 1, and in response Steinbrenner said that the owners were never more "unified and prepared for a strike." He predicted that players' union head Marvin Miller would meet his Waterloo. The owners contributed $15 million to a strike fund, and they took out insurance. The issue was free agency. Some owners wanted to be compensated with a player if they lost a free agent. The players dug in their heels. By July 12, 392 games had been lost and the All-Star Game canceled. The strike dragged on. Even Secretary of Labor Robert Donovan couldn't resolve it. A private meeting between Miller and American League president Lee MacPhail finally brought the fifty-day strike to an end. More than a third of the season was lost. The status stayed pretty much quo. Both sides lost a lot of money. Fortunately, the fans didn't become bitter, and baseball had record attendance in 1982. One of the biggest beneficiaries of the strike was the Yankees, because when the players returned, it was decided that the season would be split in half and the teams in first place at the time of the strike would automatically make the playoffs. Under manager Michael, the Yankees had finished the first half with a 34-22 record, finishing two games ahead of the Orioles. For the second half, the Yankees played only .500 ball, and George was fuming. He blamed Reggie Jackson, who was in a slump, and he blamed Gene Michael. ... The low point of George's behavior came in August 1981. With Reggie slumping, George ordered Michael to bench him one night, and another night he ordered Michael to pinch-hit the light-hitting Aurelio Rodriguez for him. George then publicly ordered Jackson to undergo not only an eye exam but a complete psychological test as well. Reggie felt humiliated and angry. The Yankees were in Detroit when Reggie returned from having taken the tests. It was early in the afternoon, and he asked Jeff Torborg to grab a couple of buckets of balls and throw batting practice. Reggie asked pitcher George Frazier if he'd shag. Frazier said yeah. "Then so sit in the upper deck," Reggie said. Torborg threw a couple dozen balls, all but a couple of which Reggie hit out of the park, most into the upper deck. When he was done, he said to Frazier, "Go tell the man what you think of my eyesight." Continued below ... A Bizarre Year - 2

George: The Poor Little Rich Boy Who Built the Yankee Empire, Pete Golenbock (2009)

Steinbrenner's treatment of Michael bordered on abuse. He kept bringing him in for meetings, ... and he threatened to fire him often, sometimes publicly. On the day Reggie returned from his tests, Michael had a surprise for the reporters. He ... said he was tired of George's phone calls after games and being told it was his fault when they lost. "I don't want to manage under these circumstances. Fire me and get it over with or stop threatening me. I can't manage this way. I've had enough."

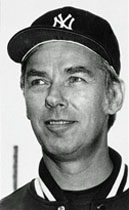

Over the next eight days, Steinbrenner kept him hanging. ... He ordered Yankee front office members not to talk to Michael while Steinbrenner called Bob Lemon, living in California, to come back and manage. After Michael was fired, George said he regarded him as "a son" and asked him to resume his duties as general manager. Michael told George he was a good manager. "Sure you are," said Steinbrenner. "But why would you want to stay manager and be second-guessed by me when you can come up into the front office and be one of the second-guessers?" George's bizarre logic made sense to Michael, who took the job. Under Bob Lemon, the team continued to play .500 ball. The Yankees finished the second half of the 1981 season with a 25-26 record. Turns out, Gene Michael didn't do so bad a job after all. The Yankees met the Milwaukee Brewers in the playoffs. After winning the first two games, the Yankees lost the next two. After the fourth game Steinbrenner stormed into the clubhouse ... and began chastising the team. Rick Cerone had made a baserunning mistake in the 2-1 loss and George said something about it. Cerone had been a whipping boy all year. It started when the catcher, whom George got in a trade from a terrible Toronto Blue Jays team, became dissatisfied with George's contract offer and took the Yankees to arbitration. ... George ... offered $350,000. Cerone felt he was worth $440,000 ... When the arbitrator ruled that Cerone deserved the $440,000, George became furious, charging the catcher with disloyalty to the Yankees, their players, their fans, and to George himself. ... Cerone blew up ... "I'm sick and tired and I'm not gonna take it anymore," he said. "Fuck you, you fat son of a bitch. You never played the game. You don't know what you're talking about." "And you won't be playing the game as a Yankee next year," Steinbrenner replied. Then he said, "And we'll find out what you're made of tomorrow." And he stalked out. Teammates congratulated Cerone for saying what many of them had been thinking but didn't dare verbalize. Steinbrenner's reaction could not have been anticipated. Cerone had embarrassed him in front of all the players, a cardinal sin ... The next day George left a card in Cerone's locker saying the incident should be forgotten. He warned him not to screw up on the base paths again. The Yankees won the pivotal game against the Brewers and went on to defeat Billy Martin's Oakland A's to win the American League pennant. Their opponent would be the Los Angeles Dodgers.     L-R: Bob Lemon, Rick Cerone, Bobby Murcer, Jerry Mumphrey Reporters and fans were particularly critical of Lemon's managerial moves in game three. George had ordered Lemon to bench Reggie Jackson ... because they were facing the Dodgers' left-hander Fernando Valenzuela. The Dodger ace was leading by a run in the eighth inning when the first two Yankees singled, and Lemon pinch-hit Bobby Murcer for pitcher Rudy May and had Murcer bunt, something critics were sure May could have done. Murcer ended up bunting into a double play. Immediately after the game, Steinbrenner ... pushed his way into the Yankees' clubhouse. Five minutes later, when the reporters were allowed to enter, Steinbrenner told them, "I didn't say anything." But when reporters started asking questions, they learned that George had said plenty, criticizing "foolish mistakes." The most foolish mistake was Lemon's ordering Murcer to bunt. George had also ripped into players Jerry Mumphrey and Dave Winfield. Said George, "There'll be changes tomorrow." ... In game four, Mumphrey was benched, and Reggie returned. Despite a batting slump, Winfield remained the number three hitter. It has been suggested that Steinbrenner ordered Mumphrey benched not because he was 2-10 in the series, but because he was scheduled to be a free agent, and his agent had taken a hard line in the bargaining. The Yankees lost the game 8-7. ... As Mumphrey stewed on the bench, in the seventh inning he watched his replacement, Bobby Brown ... misplay a routine line drive into a double. The runner ultimately scored from second with the winning run for the Dodgers. ... After the game, Lemon tried to cover up the fact that George had ordered him to bench Mumphrey. He said he had been "saving" him, though he didn't say what he was saving him for. After the 2-1 loss in game five, Steinbrenner left the press box and headed for Lemon's office in the clubhouse. He wasn't seen again until 11:30 that night, when he called a press conference at the LA Wilshire Hotel. George's left hand was in a bandage - he said he had broken a knuckle - and he had a bruise on his forehead. He began telling reporters how in the hotel elevator he had fought with two men who had been bad-mouthing the Yankees and the city of New York. Almost no one believed him. ... Steinbrenner said he cursed at the guy, and there was a brawl. "He hit me in the side of the head with a bottle, and I reacted. I clocked him with my left hand. He fell ... and the other guy hit me in the mouth. I slugged him too. The elevator door opened, and I got off ... and went to dinner." When his left hand began to throb, he called the team doctor, who wrapped it. ... A Yankees employee who was in LA at the time ... insists there had been a fight in the elevator, though what happened wasn't anything like what George said ... The employee ... was listening to a local Los Angeles radio station when the two Dodgers fans who were involved gave a recitation of what happened ... Said the employee, "... George was going down in the elevator, and ... one guy was at the elevator and the other guy was in his room when the door opened. The guy at the elevator stuck his foot in the door to hold the elevator for his buddy, and George, being George, said to him, 'Either get in or get out.' "The guy turned to look who said that, and he recognized George. He called down to his buddy, 'Look who's here.' Once again George barked, 'In or out," and the guy turned around and clocked him. "My guess is that after George was hit, he pushed the guy out of the elevator. The door closed, and George went down in the elevator." The suspicion was that George hurt his hand when he punched the door of the elevator in anger ... There was one more great George moment in 1981. After the Yankees lost to the Dodgers in the World Series, George publicly apologized to the citizens of New York. ... Among the Yankee players, Jackson reacted most strongly. "We don't need to apologize," he said. "We lost in the World Series. We have nothing to be ashamed of. ..." Baseball fans everywhere reacted contemptuously. [Reporter] Joe Flaherty ... was one of them. "We've come to a juncture where we apologize for winning a pennant. That's the insanity of the times. ... Steinbrenner is a vulgar rich man from a small burg, and he has the Big Apple to play in. It's really for the enshrinement of Steinbrenner, not for baseball. ..." Kirk Gibson's Bad Opening Day

Bruce Nash, Baseball Hall of Shame (2012)

In the most humiliating game of his storied career, Kirk Gibson got bonked on the head twice with fly balls. And it happened on, of all days, the first Opening Day that he played in front of the hometown crowd.

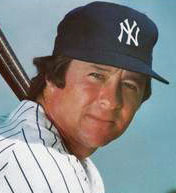

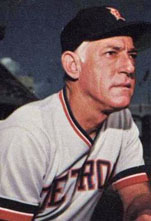

Gibson, who made his Major League debut at the end of the 1979 season, had experienced his first Opening Day in 1980, but that had been on the road. Not until 1981 did he play a season opener at home. "I was really looking forward to Opening Day," Gibson recalled. "It's like a holiday in Detroit. Everybody takes off work and goes to the game. You can't get another person in the stadium, and everybody there expects the Tigers to win." Throughout spring training, the 23-year-old outfielder had been working out in left and center field in preparation for the coming season. "I walked into the clubhouse, knowing I was going to start in my first Opening Day game [in Detroit]," he recalled. "I figured I would be playing either left or center field. When I looked at the lineup card, I couldn't believe it. There was a nine beside my name. I had to play right field. "'Oh, God,' I thought. 'It's an afternoon game, there's not a cloud in the sky, and Tiger Stadium is one of the worst places in the early spring to play right field in the day.' I went to [manager] Sparky Anderson and said, 'I think you've made a mistake in the lineup.' And Sparky said, 'No, I didn't. I know you can play right field.' Having the big ego that I do, I said, 'Sure I can.'" But it just wasn't Gibson's day in the sun. The first ball hit to him came in the second inning on a deep fly swatted by the Toronto Blue Jays' Willie Upshaw. Gibson misplayed it off his head for what the official scorer charitably ruled a standup triple.    L-R: Kirk Gibson, Sparky Anderson, Willie Upshaw In the next inning, with Toronto's Lloyd Moseby on third and one out, John Mayberry hit a soft shallow line drive to right. Gibson broke late, then charged the ball and caught it off his shoe tops. Moseby tagged up and sprinted for home. Gibson would have had a play at the plate, but as he got in position to throw, he dropped the ball. "They really started to boo me—even when I came to bat," recalled Gibson, who grounded into a force-out at second base during his next at-bat. "When I returned to the outfield, I kept thinking, 'Oh, man, don't hit another one out here to me.'" No ball came near him in the fourth. But leading off the top of the fifth, Ernie Whitt hit a high fly to right. Gibson didn't drift over toward the ball; he staggered. Squeamish fans turned their heads away, not wanting to see how he'd butcher the play. "The ball was right dead in the middle of the sun, and I wasn't real good at using my glasses at the time," said Gibson. "But I had my glasses down and I saw it, and then I thought I saw it, and then I didn't." The next thing he knew the ball bounced off his right ear, and Whitt ended up on third for a three-base error on Gibson. "I got booed unmercifully by 51,000 people, and I felt so humiliated," he said. "I'd never been booed like that in my whole life." A sacrifice fly drove Whitt home for an unearned run, giving the Blue Jays a 2–1 lead. In the top of the sixth, Toronto's Barry Bonnell lofted a fly to right. While fans held their breath, Gibson caught the ball to the mocking cheers of the unforgiving Detroit faithful. After the game, which the Tigers won 6–2, Gibson told reporters: "I had some tough times, but we won anyway. I'll learn from my mistakes. I'll improve. I fielded that last ball hit to me without any trouble. See? I'm getting better already." Deja Vu All Over Again

Unhittable: Reliving the Magic and Drama of Baseball's Best-Pitched Games (2004)

|

CONTENTS

|

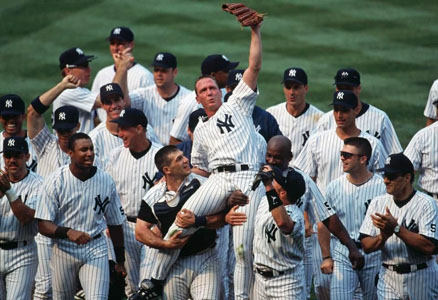

L: Joe

Girardi and David Cone after final out. R: Cone carried off.

L: Joe

Girardi and David Cone after final out. R: Cone carried off.