|

"Honorable Joes" Charles Fountain, The Betrayal: The 1919 World Series and the Birth of Modern Baseball (2016)

The Black Sox Myth Mark Halfon, Tales from the Deadball Era (2014)

It Took a Tragedy to Change the Rule

Tales from the Dead ball Era, Mark S. Halfon (2014)

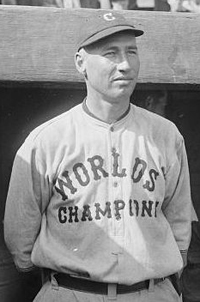

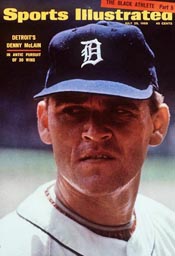

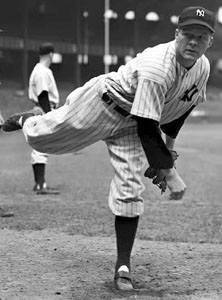

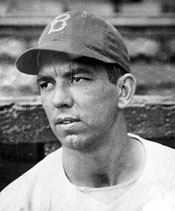

As offensive production surged, yet another advantage went the way of batters but only after one of the sport's great tragedies. On August 16, 1920, a critical contest loomed at the Polo Grounds between New York and Cleveland, teams that were in a virtual three-way dead heat with Chicago atop the American League standings. A steady rain hampered visibility and caused the ball to be mud-stained, ominous signs for batters who crouched over the plate facing pitchers who threw inside. Starting for the Yankees would be beanballer Carl Mays, whose willingness to throw at batters the Indians had observed themselves on May 20, 1918, when one of his pitches had caromed off player-manager Tris Speaker's head with such force that the ball landed in the stands. Shortstop Ray Chapman, who batted ahead of him in the lineup, had witnessed it all.

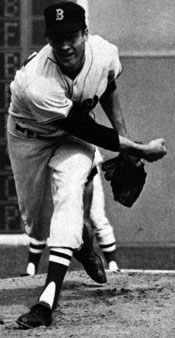

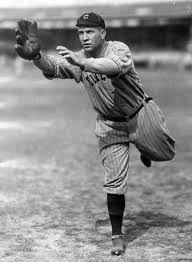

It had been two years since that incident when Chapman, regarded as one of the best "number two" hitters in baseball, led off the top of the fifth inning with Cleveland ahead 3-0. Crowding the plate as always, he had worked the count to 1-1when Mays unleased his trademark underhand fastball, scraping his knuckles on the ground as he completed his follow-through. The ball sailed directly toward the head of Chapman, who remained motionless as the baseball cracked against his unprotected skull. A terrible thud, heard by Babe Ruth in RF, echoed throughout the park as the crowd gasped in horror. Chapman fell to the ground barely conscious, unable to speak, blood pouring from his left ear. After a few agonizing minutes, he struggled to his feet and headed toward the clubhouse as a prematurely relieved crowd applauded, but the injured ballplayer collapsed and needed help off the field. Teammates rushed him to the hospital, where he passed away the next morning.    L-R: Carl Mays, Ray Chapman, Tris Speaker Mays claimed it was an accident and he had a clear conscience, Instead, he blamed umpire Tom Connolly for failing to remove the dirty baseball, but Connolly placed responsibility for the tragedy in the prodigious lap of Ban Johnson. After American League owners had complained about the excessive number of baseballs discarded, Johnson directed umpires to keep balls in play until they became "dangerous.' Connolly had been following orders. Whoever held responsibility, a darkened baseball had contributed to Chapman's death and forced a revision in policy. League officials now ordered umpires to remove scuffed, soiled, or misshapen balls and substitute new white ones. The new regulation ended a long-standing practice. Before when umpires threw in a new baseball, pitchers wiped it across the grass to rub off the gloss and tossed it around the diamond to teammates, who applied whatever substance they had at their disposal. No more. Also, given that thrifty owners expected umpires to keep baseballs in play as long as possible, occasionally one lasted a full nine innings. "We'd play a whole game with one ball, if it stayed in the park. Lopsided, and black, and full of tobacco juice and licorice stains," Crawford recalled. No more. Advantage offense. "What's the matter with me?"

Babe Ruth's Called Shot: The Myth and Mystery of Baseball's Greatest Home Run,

Ed Sherman (2014)

Huggins's death rocked baseball. The American League canceled its games the following day, and the viewing of his body drew thousands of fans. The Yankees were shocked. "I'll miss him more than anyone," Gehrig said. "Next to my father and mother, he was the best friend a boy could have. He taught me everything I know." Ruth also took Huggins's death hard. He joined the ranks of the player in the clubhouse sobbing when they learned the news. "You know what I thought of Miller Huggins, and you know what I owe to him." ... The unexpected development left the Yankees reeling and looking for a manager for the firt time since 1918. General manager Ed Barrow wanted future Hall of Famer Eddie Collins, but Collins wasn't interested. Art Fletcher, a longtime coach for the Yankees, also declined an offer to run the team. Ruth, meanwhile, had the perfect candidate in mind: himself. Why not? After all, he had been playing in the big leagues since 1914. He knew the game as both hitter and pitcher. ...

Ed Barrow looks over Babe Ruth's shoulder as he signs a Yankee contract next to Colonel Ruppert. Surely Yankees owner Jacob "the Colonel" Ruppert owed him this opportunity. Managing a big-league squad was the only thing he hadn't done in baseball. Not only was he qualified, but the position would serve as a payback for all that he had done for the franchise. Ruth pleaded his case. "I told him I knew how to handle young pitchers because I had been one myself. I knew how to handle hitters because I was one myself." Ruppert resisted the idea. All those years of flaunting the team rules when he was younger, requiring both owner and manager to discipline the slugger, were coming back to bite Ruth. Ruppert, with his German accent, always pronounced the Babe's last name "Root." In turning him down, the team owner uttered the famous line that dogged the slugger for the rest of his baseball career: "You can't manage yourself, Root. How do you expect to manage others?" Ruth had a comeback, though. He wasn't a kid anymore. He was about to turn 35. He had a new wife and was raising two daughters. Ruth tried to convince Ruppert that he had matured. His wild days lay behind him. Besides, he reasoned, who else better to know whether one of the players was getting out of line. "I know every temptation that can come by any kid, and I know how to spot it in advance," he said. "If I didn't know how to handle myself, I wouldn't be playing today." Ruppert said he would consider it, and Ruth walked out of the meeting thinking that he had a chance. It turns out that he had zero chance. Not only did Ruppert not select Ruth, but the owner further offended his star by not personally informing him. Ruth learned that Bob Shawkey had filled the position through the newspaper, which he promptly threw across the room. That wasn't the end of the matter, however. Ruth writes that he "exacted revenge" from Ruppert by demanding a big salary for 1930. Initially he asked for $100,000, eventually settling for a two-year deal at an unheard-of $160,000. He also informed Ruppert that he wouldn't be as available to play in exhibitions during the Yankees' off-days, another big revenue source for the team owner. ... [The Yankees hired former P Bob Shawkey, who lasted only one year.] Shawkey's firing also proved to be another source of frustration and embarrassment for Ruth. Again, the slugger went to Ruppert, asking to be manager. He pleaded his case for a second time. "I don't think [they] realized that I had matured, was finally a grown man with family responsibilities and not the pipe-smoking playboy [Ruppert and Barrow] had pulled the covers off in that hotel room in 1919," Ruth wrote in his autobiography. Ruppert, though, recalled those moments and used them once again to deny Ruth the job. "He recited a long list of my early mistakes - he had somebody look them up-and at the end he shrugged. 'Under those circumstances, Root, how can I turn my team over to you?'" Ruth believed that if [Joe] McCarthy hadn't become available, he might have had a decent shot at the position. ... Even so, Ruth wrote of yet another snub: "It still hurt," and that hurt lingered for the rest of his life. He desperately wanted to be a manager. Ruth wanted the authority. He wanted to show that he could be a leader of men. But no one had faith in him to do so. In 1933 he fumed when the Washington Senators named Joe Cronin as a player-manager. Cronin was all of 26 years old. "It made me scratch my head and wonder if I'd ever be mature enough to become a manager," Ruth snarked. He also wrote that Detroit owner Frank Navin had asked if he might be interested in managing the Tigers after the 1934 season. Ruth said yes and asked if he could talk after he returned from a barnstorming commitment in Hawaii. Navin was put off by Ruth's inclination to honor his commitments. Instead, after spending $100,000 to buy Mickey Cochrane from Philadelphia, Navin made the catcher the new manager. "In looking back, I can't help but wonder whether those pennants would have gone to me instead of Mickey if I had run out of the first part of my Hawaiian contract," Ruth wrote. Ruth was so desperate, he even signed with the lowly Boston Braves in 1935 because of a promise that he would become manager. He soon realized though, that the Braves had no intention of letting him run their team. Jilted and with his skills totally gone, Ruth retired after player only 28 games. Red Sox Memories

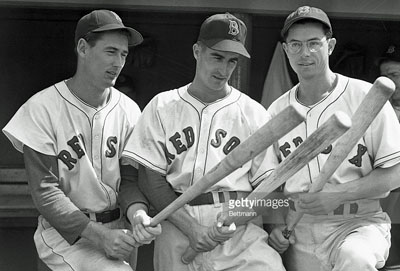

The Teammates: A Portrait of a Friendship, David Halberstam (2003)

Johnny Pesky, Dominic DiMaggio, and their friend Dick Flavin reminisced as they drove from Illinois to Florida to visit Ted Williams in 2001 Pesky said Spud Chandler, the Yankees pitcher, was tough. "God, he was mean. He'd hit you in the ass, just for the sheer pleasure of it. It was like it made him feel good. I had shined his shoes when he had pitched out in the Coast League [when Johnny was a bat boy in Portland OR]. It was as if he had some personal thing against me, as if he was insulted by my being in the big leagues. He was the worst tipper in the Pacific Coast League, by the way. In 1942, which was my first year in Boston, we were playing the Yankees and he was pitching. Ted used to like to get Bobby [Doerr] and me, and sometimes Dom, and take us where we could watch the opposing pitcher warm up to see what he had - in those days they warmed up right in front of the dugout. So we were standing there, watching Chandler, who had a very tough sinkerball, and Jack Malaney of the old Boston Post came up to us. And he said, 'Pesky, you don't have a hit off Chandler this season. You're 0 for 14 against him.' And Ted said, 'That's right, Needle [Nose]. You're always trying to pull the ball against him. He throws a heavy ball - you can't pull it. Needle, I can't pull him, and I'm a foot taller than you and about forty pounds heavier. You have to go with the pitch.' So we get to the bottom of the eighth inning and the score is 1-1, and our catcher gets to first, and Dom doubles, and we have men on second third, and first is open. So I come up. Bill Dickey is catching, and he goes out to the mound to talk to Chandler. And before I get to the plate Ted takes me aside and says, 'Needle, that's Spud Chandler out there, and he throws a heavy ball. And he is not going to walk you to get to me. So you're going to get a pitch to hit. Don't try and pull it.' It's almost sixty years later and I can still hear him telling me that ... And I get up, and I take a couple of pitches, and I get a sinker and slap it to left, and two runs score. I'm on first and Chandler is going crazy, it's apparently very personal to him - just screaming at me. 'I'll stick one in your ear, you little shit. I'll get you.' Ted is standing at the plate, just grinning away. Ted steps in, and Chandler is still screaming at me, 'You little shit, I'll get you!' And it's like he's forgotten Ted is the hitter. He finally pitches to Ted, and Ted hits a rocket to right field. Home run! And Ted comes in to the dugout, and he's saying where is our horn-nosed little shortstop - 'Didn't I tell you about Chandler? Didn't I tell you? Chandler was so mad at you, he forgot I was the next hitter.'"   L-R: Ted Williams, Johnny Pesky, and Dominic DiMaggio; Spud Chandler As they neared Philly, Dominic was saying that he was rather puzzled as to why he had been invited there. ... In an unusual feat for one of the younger players, Dominic had even managed to forge a genuine friendship with the great Lefty Grove, who had started his career ... in 1925 with the Athletics and had come to Boston in 1934 when Athletics owner and manager Connie Mack was selling off his best players due to financial difficulties. Lefty was a hard man, known as much for his misanthropy as for his brilliant pitching ...

Dominic's relationship with Grove did not start well. When Dom joined the Red Sox in the spring of 1940, Johnny Orlando, the clubhouse boy, brought him around the locker room and introduced him to everyone. "The only two who weren't there were Jimmie Foxx and Lefty Grove," recalled Dominic, "but pretty soon Foxx shows up and sticks out his hand and says, 'Welcome aboard, kid." But then Grove comes by and walks right by me and doesn't say a thing. And I'd heard that he was quite temperamental and so for two weeks we didn't speak. Every day it seemed we were in the elevator together, but we didn't talk. Not a word was said. And I was thinking, I'm a rookie, and rookies don't speak unless they're spoken to. Especially to Lefty Grove. So then a friend of mine from Boston came down, and said, 'What's this, I hear you don't talk to Lefty Grove?' And I said, 'You've got it all wrong, Grove doesn't speak to me ...'" The next day when Dominic was returning to the team hotel, he had to pass two rocking chairs on the front porch. Grove was in one and Orlando in the other. Dominic got very nervous. This was going to be a great social test: "My heart is beating terribly, but I get my nerve up, and I say, 'Hello, Lefty,' and he bounds up, grabs me, hugs me, tells Johnny Orlando to sit somewhere else, tells me to sit in Orlando's chair, and we sat and talked for hours. We became fast friends after that. I caught the last ball hit on his three hundredth victory, the last game he pitched. And I think I was one of two players invited to the dinner to celebrate that win - Jimmie Foxx was the other one." You Were Where? You Can't Hit the Ball with the Bat on Your Shoulder,

Bobby Bragan as told to Jeff Guinn (1992) Bobby Bragan was the backup C on the 1947 Dodgers who appeared in only 25 games and spent most of his time in the bullpen. In 1947 we clinched the pennant in a road game at Pittsburgh. There was a big celebration in the clubhouse with champagne for everybody to pour over everybody else. I was truly excited about playing in a World Series. Having recognized my limitations as a player, I knew that this would undoubtedly be the highlight of my active career. I called Birmingham and insisted that George and Corinne [his parents] fly to New York at my expense to attend the Series with Gwenn and our children.

We had the toughest possible opponent. ... The Yankees had won 97 games ... The Series got off to a rough start for Brooklyn. Playing at Yankee Stadium to open up we lost the first two games ... We switched to Ebbets Field for the next three games. Needless to say, I hadn't seen any action yet beyond warming up relief pitchers in the bullpen. I wasn't unhappy, just glad to be part of a team playing in the World Series. George and Corinne were enjoying themselves anyway. ... If this World Series had ended in five games I'd never have been able to say I played in one. The Dodgers came back on our home field to win Game Three 9-8 and Game Four 3-2. ... But the Yankees won Game Five 2-1 ... and the Series returned to Yankee Stadium ... The Yankee march was interrupted in Game Six, though, and this remains my most priceless baseball memory.    L-R: Bobby Bragan, Joe Page, Burt Shotton Things didn't look good as Brooklyn came to bat in the top of the sixth inning. Vic Lombardi had been shelled by Yankee hitters, and though Ralph Branca had come on to hold New York, Joe Page took over on the mound for the Yankees in the fifth obviously able to protect a 5-4 lead into eternity.

In New Jersey, my father-in-law was watching the game on television. He was astonished in the top of the sixth when it was announced Bobby Bragan would be pinch-hitting for Ralph Branca. "I watched you run in from the bullpen, go to the dugout, select a bat, and walk to the plate," he told me later. "The closer you got to home plate, the tighter the muscles in your face became." It was no optical illusion. We had two runners on against Page. The lefthander had handcuffed us throughout the Series, and it was obvious if we didn't get to him now he'd hold us off the rest of the way and the Yankees would be champions. In my mind, the game is still being played. I can see the sky, smell the grass, hear the crowd. I can also feel my knees shaking. They were, hard. Major leaguers get nervous in the same way anyone else would. The difference is we can perform anyway. With a count of one ball and two strikes, I hit a line drive down the left field line. It might have been five feet fair, and I pulled into second base with a double. My RBI tied the score. Immediately, Burt Shotton sent in Dan Bankhead to run for me. I trotted off the field into our dugout, to be met there by teammates who pounded me on the back. It was wonderful. Euphoria. I learned later that George and Corrine, having long since given up ever seeing their son play in the World Series, were both in the restroom during my time at bat. Well, nothing is perfect, but this moment came close. Pee Wee Reese followed my double with another hit. The Dodgers took the lead and held it, making Joe Page the losing pitcher. I couldn't celebrate much. After we were finally retired in the top of the sixth I got my catcher's mitt and ran back to the Yankee Stadium visiting bullpen. Tommy Henrich, the Yankee right fielder, told me later he'd always admired how I'd gotten to run in across the field to get to bat, got my double, and then got to run back to the bullpen amid the cheers of Brooklyn fans in the crowd. God, I felt 10 feet tall. When I got home to Brooklyn after the game, eight kids ranging in age from six to fourteen who lived in the same apartment building were lined up on the sidewalk with cardboard signs saying, "Our Hero." It added to my joy. The Mick's Sad Journey into Retirement Marty Appel, Baseball Digest, September/October 2018

"Oh, Charlie"

Dick Williams and Bill Plaschke, No More Mr. Nice Guy: A Life of Hardball (1990)

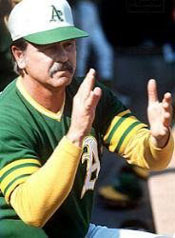

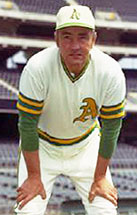

Manager Dick Williams' 1973 Oakland A's were attempting to defend their World Series championship.

We finally climbed about .500 in mid-May and were actually playing well when the Kansas City Royals came to town May 18. But once again we couldn't let a good thing alone. It was time for new guy [Billy] North, who fit in well here, to cause another scene. In the sixth inning against the Royals he singled to score the tying run, he stole second, and then he scored on a single to give us the lead. Everything was fine until North came to the plate in the eighth inning. The Royals pitcher was Doug Bird, just another reliever. Or so we thought. On Bird's first pitch North swung and missed and released the bat, lofting it next to the pitcher's mound. Losing the bat is a common, natural occurrence when a batter is fooled by an off-speed pitch. What happened next is not so common. Walking to the mound, just before he reached his bat, North stopped, turned, and nailed Bird with a right to the jaw. Bird dropped, but North didn't stop - he jumped on him and pounded him. I was watching this like it wasn't really happening, like it was some scene staged as a joke. What in the hell is Bill North doing pounding a guy after the guy throws him a strike? North was thrown out of the game, which only made me spend the final couple of innings wondering. Did I have an insane man on my hands? I mean, more insance than the guys I already had? First thing I did when I got into the clubhouse afterward was call North to my office. Before I could even ask him what the hell had happened, he told me. Three years earlier Bird had plunked North in the head with a fastball in a minor league game. It was no ordinary plunk, it cracked his skull. North, needless to say, hadn't forgotten. He apoligized to me but claimed this was the first time he'd seen Bird since and he had no choice. Now it was my turn to go crazy. "Since this was such a personal grudge, why didn't you just go to his hotel room, open the door, and pop him one?" I asked. "Or why didn't you at least tell us, and we would have gotten back at him some other way! Why the hell did you have to fight him by yourself, on your own, without any of us knowing? Billy, damn it, this is a team that doesn't just play together, it fights together!" Yes, I can't believe I made that last statement. That showed just what kind of team I believed I was managing.    L-R: Dick Williams, Billy North, Doug Bird Right away the media rushed to me for comments on the explosion, which I could hear even in my office. After talking with Noren, I announced that I agreed with my coach. As if you thought I'd say anything else. Just as I hope my coaches will back me, I back them. I told the media, "Reggie doesn't need to be so sensitive. And furthermore, Noren was right. If Reggie did play defense like he swings the bat, we'd all be better off." The next day Reggie saw my quotes, and suddenly he's madder than hell, not at Noren but me. That morning, as we were boarding our flight to Baltimore, Reggie stopped as he passed me on the plane and said, "Don't even talk to me again. Put my name in the lineup card and leave me alone." Before I had a chance to tell him that I wasn't even obligated to put his name in the lineup card, he was gone down the aisle. We blew across the country that night on a ride turbulent with tension. Reggie wanted to kick my ass, and increasingly I wanted to kick his. And - oh, yes - we were in first place. [Owner Charlie] Finley loved this stuff. He loved people to be uneasy, uncertain, worried enough about their jobs and their egos to play their butts off. I preferred to treat them like men and hope they'd play their butts off because they wanted to win.    L-R: Reggie Jackson, Irv Noren, Charlie Finley "The Hemorrhoids Guy"

"The Game I'll Never Forget," George Brett as told to Barry Rozner

Baseball Digest July/August 2016

When George Brett was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1999, he received 98.2 percent of the vote, the sixth-highest percentage of votes ever. ... Brett played in 13 All-Star games and ranks 18th all-time in total bases, 24th in MVP shares, and 36th in RBI. ...

While accumulating this extraordinary resume, there was a stretch in which a portion of his anatomy drew as much attention as his bat - the result of a well-publicized battle with hemorrhoids during the 1980 World Series. "For three years after that World Series, everywhere I went I was that guy, the guy with a pain in his butt," Brett says now with a laugh. "I was 'The Hemorrhoids Guy' in every stadium. ... you hear every joke you can imagine about me and my hemorrhoids. But that all changed on July 24, 1983." The story really began about two weeks before that, when the Yankees were visiting the Royals and New York third baseman Craig Nettles noted something after a Brett at-bat, and said something to Yankees closer Goose Gossage. "I didn't find this out until many years later," Brett explained. "But I guess Nettles thought he saw the pine tar too far up my bat and he told Goose that if I got a big hit in that series, they were going to show the umpires the bat and try to get it overturned. It didn't become an issue then, so they let it go. Little did I know what they had planned for me when we got to New York a couple weeks later." Yes, the Yankees had been watching for a while and plotting against Brett if the proper situation occurred, and manager Billy Martin was right in the middle of it all. "Of course Billy was in on it," Brett laughed. "He was always looking for an angle." America got a lesson in pine tar that Sunday afternoon, and soon every baseball fan knew that pine tar is allowed from the bottom of the bat and could extend 18 inches toward the top. There was no real reason for the rule, other than the fact that pine tar was ruining baseballs and too many were getting tossed out of play. ... The Yankees were leading by a run on that July day at Yankee Stadium, with two outs in the top of the ninth and the tying run on first base. Up stepped Brett, one of the best hitters of all time, to face Goose Gossage, one of the best closers of all time. Gossage tried to fire his trademark fastball high and unhittable, but Brett went up shoulder-high and hammered it deep into the right-field bleachers for a two-run homer and a Royals lead. "Here's something you probably didn't know," Brett said with a smile. "When a player hits a home run, the bat boy is supposed to get the bat and take it back to the bat rack, where it mixes in with all the other bats. If he had done that, they wouldn't have had the bat. I wasn't trying to hide anything. "The bat was legal," Brett explained, "but the kid was a George Brett fan in New York. I loved him. He was a good kid, but he wanted to shake my hand after I crossed the plate. So he's standing there holding the bat when I crossed home plate. Just standing there holding it, like a smoking gun. "That's what gave Billy and those guys a chance to go get the bat and show the umpire. But they wanted the bat and they were going to get it no matter what, whether the kid stood there or not." With Martin yelling from the dugout, Yankees catcher Rick Cerone grabbed the bat from the batboy and gave it to home-plate umpire Tim McClelland, who got together with his crew and discussed the bat. They examined it, but had no ruler, so McClelland - a rookie umpire - set the bat down on home plate, which is 17 inches across.    L-R: George Brett, Billy Martin, Frank White The game was over, but the firestorm was just about to start. Everyone remembers most what happened next. "I went nuts," Brett said, laughing. "I was going to get my money's worth." An enraged Brett came charging out of the dugout and tried to get at McClelland, waving his arms like a madman. He was held back by McClelland's three fellow umpires. ... The Yankees celebrated and skipped off the field, while Royals manager Dick Howser protested the ruling and the result of the game. During the melee, however, the Royals' Gaylord Perry grabbed the bat from the umpire and ran toward the dugout. "Gaylord was big into memorabilia, so he must have thought it would be great to have that bat in his collection," Brett said. "He tossed it to someone else, who tossed it to someone else ... the umpires chased them all up the tunnel and got the bat." The umpires wanted the bat as evidence to turn over to American League president Lee MacPhail, which was the best thing that could have happened to Brett and the Royals. Four days after "the pine incident," MacPhail ruled the pine tar didn't help Brett hit the homer and awarded the Royals the two runs. At a later date, the game would continue from that moment with the Royals leading 5-4. A full 25 days later, both clubs were back at Yankee Stadium to finish the game. Minus Brett. "I watched the last four outs of the game from an Italian restaurant in Newark because I had been thrown out of the game for charging the umpires - even though the game was over," Brett said. "We had flown in from Detroit on an off day on the way to Baltimore. So we stopped and the guys went to the park. ... Plus, a few others were missing. Bert Campaneris had started the game at second base for the Yanks, but he was hurt, and center fielder Jerry Mumphrey had been traded. Billy Martin was so mad about the MacPhail decision that he offered his own version of a protest. For the final Royals out in the top of the ninth, he played pitcher Ron Guidry in center field and first baseman Don Mattingly, a left-hander, at second base. Neither saw the ball on the last out in the top of the ninth, and Kansas City closer Dan Quisenberry retired the Yankees in the bottom of the ninth to secure the 5-4 Royals victory. The bat is now in Cooperstown. Nine years later, McClelland was working the game when Brett recorded his 3,000th hit and congratulated him during the festivities. ... "I went from 'The Hemorrhoids Guy' to 'The Pine Tar Guy,' which was much better for me. So I always said 'thank you' to Billy Martin because I went from something pretty embarrassing to being remembered for hitting a home run. It worked out very well for me." Indian Summer

Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum,

Paul Hagen (2018)

|