|

Baseball Short Stories - 10

Student of the Game

Halfon, Mark S. Tales from the Deadball Era. Potomac Books, Inc. (2014)

Ty Cobb spent untold hours pondering baseball's nuances in search of an edge, regardless of how slight it appeared to less discerning observers. Critics chastised him for swinging three bats while waiting on deck, but he knew that it made a single bat feel lighter and enabled him to swing more quickly; after reaching base, he kicked loosely placed bags forward to gain valuable inches; when sliding, he watched the eyes of fielders to determine the trajectory of the ball and aimed his toe at the tip of the bag farthest away from an outstretched glove; and sharpened spikes aimed high sent a clear and distinct message to anyone who dared stand in his way. ...

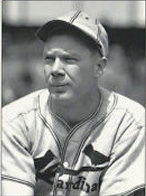

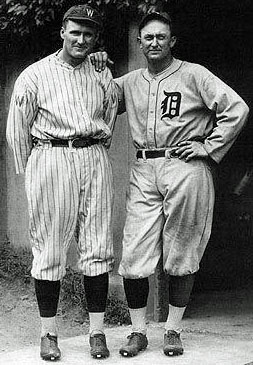

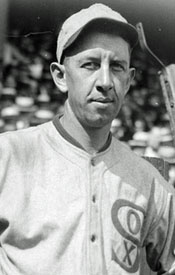

Cobb's obsession with the fine points of the game earned him countless advantages and paid off handsomely in his confrontations with Walter Johnson. Their careers overlapped from 1907 to 1927, and Johnson initially dominated the head-to-head, especially in 1913 and 1914, when Cobb went a dismal 3-for-26 against the pitcher. But that was about to change. The turning point came on August 10, 1915, when a Johnson fastball struck the forehead of Detroit third baseman Ossie Vitt, who fell to the ground motionless before regaining consciousness. After a pinch runner replaced Vitt, Johnson surrendered four runs. Cobb recalled, "I thought about it and realized that Johnson was so nice a guy that he never dusted off a batter. Gradually I began to crowd the plate . . . I was gambling that Johnson would be so afraid of hitting me that he'd work to the outside corner and that he did. The Georgia Peach averaged .437 against the Big Train over the next twelve years. Although Cobb improved dramatically, he may have embellished his account of events since it is doubtful that Johnson—baseball's career leader in hit batsmen—had a fear of hitting batters.    L-R: Ossie Vitt, Walter Johnson, Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford If the Cubs threw the 1918 World Series,

it was a Cardinal that fixed it The evidence is a little sketchy, but the "Original Curse" could have begun with a fix orchestrated by a Cardinals pitcher

Ben Godar, vivaelbirdos.com (Apr. 20, 2016) We all know the story of the 1919 Chicago Black Sox, the pinnacle of an era when ballplayers colluding with gamblers and throwing games was not uncommon. But it is believed by many that the Chicago Cubs threw the 1918 World Series against Babe Ruth and the Boston Red Sox. If they did, it was likely a Cardinals pitcher by the name of Gene Packard who orchestrated the fix, and created what author Sean Devaney dubbed "the Original Curse."

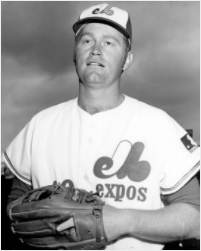

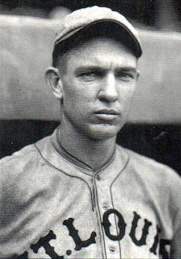

Gene Packard was the very definition of a journeyman. A right-handed swingman (before that term was even in use), he played for five different teams in an eight-year career, and actually accumulated more value with his bat than with his arm. Packard joined the Chicago Cubs for the 1916 season, after playing for the Kansas City Packers of the Federal League during the only two years of their existence. In the Cubs first season in Wrigley Field, Packard joined a clubhouse that contained three other players who would ultimately be implicated for fixing games. Released midway through the 1917 season, Packard caught on with the Cardinals and pitched in St. Louis for the remainder of that year and all of 1918. He was traded to the Phillies during the offseason, appeared in 21 games in 1919 and then was out of baseball. Or perhaps I should say, he was out of playing baseball.     L-R: Gene Packard, Bill Veeck Sr., Ban Johnson, Max Flack That Grand Jury shifted its focus to fixing in baseball more broadly, and ultimately brought to light the 1919 Black Sox Scandal. The Cubs/Phillies incident was largely forgotten, but during his testimony, American League President Ban Johnson said a Kansas City Reporter had informed him one of the principals involved in fixing the Cubs/Phillies game was "Eugene Packard, a former major league baseball player." According to Johnson's testimony, a notorious Kansas City gambler went through Packard to get his former Cubs teammate Claude Hendrix, the scheduled starting pitcher, to throw the game. As the Grand Jury was shifting its focus to the 1919 White Sox, their owner, Charles Comiskey, was already deep into his own investigation of his players and their actions. His right-hand man, Harry Grabinar, kept a detailed diary of the investigators findings. Among the names listed in that diary was the following entry: "Gene Packard: 1918 series fixer" In Grand Jury testimony which only became public four years ago, White Sox pitcher Eddie Cicotte said the players had heard the Cubs threw the 1918 series and were paid $10,000 for doing so. In fact, it appears that Ban Johnson was aware during the 1918 season of a plot to fix the World Series by a St. Louis Gambler named Henry "Kid" Becker. Johnson even went to American League owners looking for money to hire investigators, but was rebuffed. Many of those reports also suggest that Becker abandoned his plan because he also couldn't raise the money to fix the 1918 series. Becker and his associates were also alleged to be involved with Arnold Rothstein in the 1919 fix, though Becker himself was murdered before that plot came to fruition. Despite the original impetus for the Grand Jury involving the Cubs, and the allegations about the 1918 series, the Grand Jury would ultimately deliver indictments only related to players and gamblers involved in the 1919 series. Those eight players would be banned for life by newly-appointed Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, and both baseball and the courts turned a blind eye to the other allegations which had come to light. Gene Packard stayed away from baseball for the rest of his life, as you might expect from a man who narrowly escaped a Grand Jury indictment. He died in Riverside, California in 1959. So, was the 1918 World Series fixed? Unless some truly "smoking gun" document comes to light, we will probably never know. But the atmosphere was certainly ripe. Players salaries were slashed in 1918, and at the time of the series, it was widely believed that the 1919 season would be cancelled and most players drafted to fight in World War I. Overall, the Cubs played well in the series - but there were notable exceptions. The shenanigans seemed to begin after Game 3, when the teams rode the train together from Chicago to Boston and reportedly discussed what they had just learned would be their paltry World Series shares. Cubs Right Fielder and Leadoff Hitter Max Flack was picked-off twice in Game 4. In the same game, with Babe Ruth coming to the plate and two men on, Flack positioned himself very shallow in right field. Cubs Pitcher Lefty Tyler repeatedly waved Flack to play deeper, but Flack ignored him. Ruth drove a triple over Flack's head, driving in two runs. Later that game, Cubs Reliever Phil Douglas fielded a sacrifice bunt and threw wildly into right field, allowing the winning run to score. Douglas would be banned from baseball a few years later after offering to retire in the midst of a playoff race if he were paid to do so. Before Game 5, both teams refused to take the field in protest of their diminished Series shares, delaying the game by an hour. In Game 6, Flack dropped a routine fly ball which allowed two Red Sox to score. They won the game 2-1 and clinched the series. The evidence is largely circumstantial, and some of the sources a bit sketchy. Grabinar's diary, which pegs Packard as the "1918 series fixer", has been lost, so the only record of that account comes via Bill Veeck Sr.'s autobiography (though other items from the diary as reported by Veeck have been verified). But as circumstantial evidence goes... a lot of things line-up. Many league officials believed there was at least a plot to fix the 1918 series, whether or not it was executed. And if a St. Louis Gambler were to fix the series, it's easy to where Gene Packard would fit in: A Cardinals pitcher who had played for those same Cubs and knew which players might be open to such a proposition. Would Packard do such a thing? Well, he was implicated just two years later for doing exactly that in the Cubs/Phillies game. Maybe it didn't happen. But maybe the Cubs did throw the 1918 World Series. And maybe - if you believe in such things - that shameful act put a curse on the team that continues to this day. And maybe a Cardinal player was the serpent that dangled the apple. And if that serpent was really the devil, and the curse is magic... Fall from Grace

Fall from Grace: The Truth and Tragedy of "Shoeless Joe" Jackson, Tim Hornbaker (2016)

A single moment can make a hero.

Throughout the history of sports, legends have been born as a result of extraordinary performances by remarkable athletes. In more than a century of Major League Baseball, there are an untold number of time honored moments; occasions in which records were set, championships were won, and heroic feats were performed by individual players, forever establishing their immortality. These defining moments are rare, making them even more special, and the unexpected triumph of a player and team were cherished by fans for their exclusivity. For those at Comiskey Park on the South Side of Chicago on July 4, 1916, such a moment arose in the ninth inning of an emotional game against the St. Louis Browns. Independence Day was always a big drawing event, and families from throughout the city traveled to the stadium to enjoy the national pastime. This year was no different. An estimated 25,000 people jammed the park, and the local crowd wanted to see the White Sox win the second game of a doubleheader after losing the morning affair, 2–1. Headed into the contest, no one could’ve predicted how remarkable this event was going to be. In fact, the game was going to be so overwhelmingly special that a superstar was about to become a legend right before their eyes. Things were going well for the home team until the top of the ninth, when the Browns produced two runs, leaving the Sox in a hole headed into the bottom of the inning. Eddie Collins, the faithful second baseman, started a last ditch rally by singling his way on base. He was succeeded in the lineup by slugger Joe Jackson of South Carolina, then in his sixth full big-league season. Acknowledged for having one of the most distinctive nicknames of the Deadball Era—or any era for that matter — "Shoeless Joe" was an enigma in many respects. Naturally gifted, he didn’t play the game with science but rather with an innate flair that differed from his contemporaries. He was known for denting outfield walls with his powerful drives, and extra base hits were commonplace for Jackson. Joe was popular in Chicago, but since joining the Sox in August 1915, had yet to live up to the hype in the minds of some critics. At bat against the Browns in the ninth, Joe readied himself in the batter’s box and waited patiently. His opponent on the mound, Bob Groom, was a tall and imposing right-hander, but to Jackson every pitcher looked the same. He didn’t care who was out there, nor did he anticipate any specific pitch. Groom’s offering looked right, and Joe gave the fans what they were hoping for: a tremendous blast to deep right-center. The ball landed safely and Jackson rounded the bases with all of his immense might. He had one thought in mind: scoring. That meant he was going to ignore the halt sign given by manager "Pants" Rowland at third base. But Rowland could see what Jackson couldn’t, and knew the ball was already back in the infield. He knew a play at the plate was going to be too close to let him go. Jackson didn’t seem to care one way or another. The Browns’ catcher, Hank Severeid, was an experienced man and could certainly hold his own. He eyed the throw and planted himself for a collision while at the same time preparing to make the tag. Jackson was blinded by his determination. The fact that a 6-foot, 175-pound backstop was standing in front of the plate did not deter him for a second. Moments later the inevitable occurred, and Jackson made impact. Home plate umpire Billy Evans saw the ball beat the runner and called Joe out, but reversed his decision after seeing the ball fall free from Severeid’s control. The latter had dropped it, and Jackson was safe. Since Collins had scored as well, the game was now tied and the holiday crowd erupted into an immense roar. Notably, Jackson was unaware of his safe status when Evans made his call. The reason was because he smashed the back of his head on the ground during the forceful slide, and nearly knocked himself unconscious. Within seconds of realizing what was transpiring before them, spectators collectively hushed, acknowledging what apparently was a serious injury to Jackson. A handful of minutes passed—which probably seemed like an eternity—before he was helped to his feet. Again, the crowd responded audibly, grateful that Joe wasn’t badly hurt. His teammates tried to allow him to walk on his own, but Jackson fell to the ground en route to the dugout and was quickly carried off the field. He received immediate treatment, including icepacks, and recovered enough to return to the outfield the next inning. It was an amazing display of courage which wasn’t lost on the humongous throng of fans.     L-R: Joe Jackson, Eddie Collins, Pants Rowland, Hank Severeid Headed into the 1916 season, sportswriters and fans alike were concerned about Jackson’s ability to meet expectations. His career statistics were in decline, and his days of challenging for the league batting championship were a thing of the past. To make matters worse, Joe failed to provide the spark needed for the Sox to win the 1915 pennant, and rumors circulated about a possible trade after the season. The questions about his ability, health, and overall attitude were discouraging to Jackson, but he knew deep down the need to come into his own while wearing a Chicago uniform. He had to demonstrate that he was all-in, and deeply committed to the franchise. Independence Day 1916 allowed him to do just that, and the fans decided that he was one of them. He was a big-hearted warrior on the diamond and his actions earned him a mountain of respect from an eternally loyal group of enthusiasts. And, in effect, his legend in Chicago was born. Over the years Joe Jackson took on a mythical nature, and a number of mainstream factors played a role. Some of it was indeed legitimate, while other aspects were moderately fabricated to create a sellable product, whether it was a book or film. But Jackson didn’t need any additional color to be an interesting story. His rise from a small mill community to the pinnacle of baseball was fascinating, and his accomplishments spoke for themselves. His .408 batting average as a rookie in 1911 is a record that remains to this day. Everything from his personal quirks to his sense of humor and the way he interacted with spectators made him a one-of-a-kind ballplayer. His popularity was genuine because of his natural charisma and the image he portrayed to the public. And for that reason, nothing needs to be manufactured to produce a true representation of Joe Jackson. He lived an incredible life. In many ways, he was a typical American ballplayer, possessing the physical characteristics of a professional athlete. He was better than his size, with proportioned muscles and extraordinary strength. Gifted with long arms, which accentuated his abilities at the plate, Joe was able to make contact with pitches far outside the box. And if the ball looked good to him, he’d often reach out and give it a wallop. There was no specific discipline behind his efforts, just a natural gift. His piercing dark eyes saw the ball in all its clarity, and with tremendous hand-eye coordination he rarely had trouble meeting a pitch with perfect timing, speed, and strength. As a result, he exemplified the prototype of a baseball slugger. Limited by personal weaknesses—particularly a lack of formal education—Jackson was strong-willed, but easily susceptible to the smooth talking of others. Throughout his life he was ensnared by crafty manipulators, and usually his wife Katie was the voice of reason. But there were times when Katie was not around, or when Jackson’s own eccentricities took over. In the case of the 1919 World Series scandal, Joe found himself embroiled in a situation way over his head. Although he had options, he made the best decisions he could and, in the end, paid the price for what transpired. The entire story remains haunting to a certain degree, and the truth behind Jackson’s exact involvement is shrouded by an overwhelming number of contradictory versions. These inconsistencies hurt Jackson in his attempts to clear his name during his lifetime and impeded advocates in much the same way since his death in 1951. Of course, the situation damaged the reputation of Jackson and cast him from the good graces of baseball, but “Shoeless Joe” still remains a clear-cut enigma of the game from any history perspective. The absence of his name on a plaque on the walls of Cooperstown at the National Baseball Hall of Fame is evidence of Jackson’s cataclysmic fall from the plateaus of the national pastime. Regardless of what happened at the 1919 Series and in its aftermath, Joe was the true embodiment of a baseball idol prior to that horrendous episode. The vivid memories of his powerful drives, his never-ending chase of Ty Cobb and the batting championship, and the way he naturally smiled during the course of a ballgame made him an inspiration to the young and old. These facts made his eventual banishment hurt all the more. Sale of the Century

Bill Francis, Memories and Dreams: Official Publication of the

Baseball Hall of Fame (Winter 2019) 100 years later, Yankees' purchase of Babe Ruth's contract is still being felt throughout the baseball world. For fans of the Boston Red Sox, the unthinkable, unimaginable, unfathomable happened 100 years ago with the sale of Babe Ruth to the Yankees.

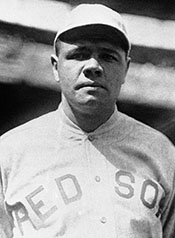

Ruth, all of 24 years old, had made the transition from strong southpaw pitcher to the premier slugger in the game by 1919. Now patrolling LF for Boston, and thanks to his powerful left-handed stroke, he clubbed 29 HRs that set a new single-season big league record. But then the news broke. Ruth would soon be playing 77 games each season at the Polo Grounds - his new home ballpark until Yankee Stadium opened in 1923 - with its short RF fence. It was announced on Jan. 5, 1920 - though the transaction had been consummated a week earlier - that Ruth was now a member of a rival American League franchise. Newspapers across the country shared the news with provocative headlines: "Red Sox Sell Ruth for $100,000 Cash" read The Boston Globe; "Ruth Bought by New York Americans for $125,000, Highest Price in Baseball Annals" blared The New York Times; "New York Yankees Buy Babe Ruth from Boston Red Sox" stated the Chicago Tribune. "Like all things Ruthian, everything about Ruth's sale from the Red Sox to the Yankees was outsized," said Tom Shieber of the National Baseball Hall of Fame staff. "The price tag was unparalleled in sports history, the story was obsessively covered in the press and every last detail was voraciously consumed by baseball fans nationwide. With the possible exception of the Louisiana Purchase, what other acquisition has reached the same level of long-term recognition in the American public's conscience?" So how did it come to this, that Ruth, a legend in his own time, was shipped out of Boston just as his offensive prowess was emerging? Coming off a 1919 season in which he led the Junior Circuit not only in homers but also with his 113 RBI and 103 runs scored, the Colossus of Clout wanted a new contract that would pay him $20,000 per season. Prior to the 1919 season, Ruth had signed a three-year deal with the Red Sox that would pay him $10,000 annually. "You can say for me," said Ruth to The Boston Globe on Oct. 24, 1919 ... "that I will not play with the Red Sox unless I get $20,000. You may think that sounds like a pipedream, but it is the truth. I feel that I made a bad move last year when I signed a three-year contract to play for $30,000. The Boston club realized much on my value, and I think that I am entitled to twice as much as my contract calls for."     L-R: Babe Ruth, Harry Frazee, Jacob Ruppert, Miller Huggins "The price was something enormous, but I do not care to name the figures. It was an amount the club could not afford to refuse," said Frazee ... I should have preferred to have taken players in exchange for Ruth, but no club could have given me the equivalent in men without wrecking itself, and so the deal had to be made on a cash basis. No other club could afford to give the amount the Yankees have paid for him, and I do not mind saying I think they are taking a gamble. With the money, the Boston club can now go into the market and buy other players and have a stronger and better team in all respects than we would have had if Ruth had remained with us. "I do not wish to detract one iota from Ruth's ability as a ballplayer nor from his value as an attraction, but there is no getting away from the fact that despite his 29 HRs, the Red Sox finished sixth in the race last season," Frazee added. ... "I am not at liberty to tell the price we paid," smiled Yankees co-owner Jacob Ruppert ... "I can say positively, however, that it is by far the biggest price ever paid for a ballplayer. Ruth was considered a champion of all champions, and, as such, deserving of an opportunity to shine before the sport lovers of the greatest metropolis in the world." Then, in a bit of foreshadowing, Ruppert added, "It is not only our intention, but a strong life purpose, moreover, to give the loyal American League fans of greater New York an opportunity to root for our team in a world's series. We are going to give them a pennant winner, no matter what the cost. ... Yet the fans can rest assured we by no means intend to stop there. Eventually we are going to have the bes team that has ever been seen anywhere." Ruth, contacted in Los Angeles - where Yankees manager Miller Huggins helped secure a contract that would pay the HR king $20,000 per season in 1920 and '21 - claimed not to be surprised by his sale to New York, noting: "When I made my demand on the Red Sox for $20,000 a year, I had an idea they would choose to sell me rather than pay the increase, and I knew the Yankees were the most probable purchasers in that event." ... While the official sale price of Ruth was not made public at the time of the transaction, numbers were speculated about. According to modern research compiled by Michael Haupert, professor of economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, the actual purchase price was $100,000, payable in four annual installments of $25,000 at 6% interest, with New York making the first payment on Dec. 19, 1919. ... Welcome to the Bigs!

The Baseball Hall of Shame: The Best of Blooperstown, Bruce Nash and Allan Zullo (2012)

For the Most Inauspicious Major League Debuts of All Time, The Baseball Hall of Shame Inducts: BILLY HERMAN

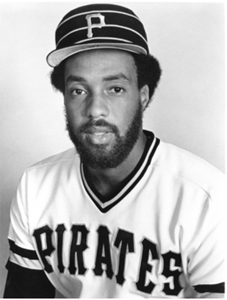

Billy Herman can't remember a whole lot about his big league debut, even though it was a memorable one. Thrilled at getting a chance to break into the starting Chicago Cubs lineup, Herman was determined to show he belonged. In his first at-bat in the Majors, he singled off Cincinnati Reds hurler Si Johnson, much to the delight of the Wrigley Field crowd. In his next at-bat, Herman, his confidence growing, dug into the batter's box. On Johnson's first pitch, the rookie took a tremendous swing and fouled the ball straight down. It hit the ground in back of the plate and, with wicked reverse English, bounced straight up, smacking Herman in the back of the head. So a sterling career that spanned two decades highlighted by a .304 lifetime batting average started out in the most forgettable—for him, at least—way possible. Billy Herman was carried off the field on a stretcher—knocked out cold by his own foul ball.Second Baseman · Chicago, NL · August 29, 1931    L-R: Billy Herman, Doe Boyland, Doc Hamann DOE BOYLAND

In his first Major League at-bat, Pittsburgh Pirates rookie Doe Boyland struck out—while sitting on the bench. In the seventh inning of a home game against the New York Mets, Pittsburgh manager Chuck Tanner sent Boyland in to pinch-hit for pitcher Ed Whitson. The count was 1-and-2 on Boyland when Mets right-handed pitcher Skip Lockwood had to leave the game because he hurt his arm. New York switched to southpaw Kevin Kobel, so Tanner, going by the book, lifted the left-handed-swinging Boyland and put in right-handed batter Rennie Stennett to pinch-hit for the pinch hitter. While Boyland watched helplessly from the bench, Stennett struck out on Kobel's first pitch. Under the scoring rules, the strikeout was charged to Boyland for his inauspicious debut.Pinch Hitter · Pittsburgh, NL · September 4, 1978 DOC HAMANN

Cleveland Indians rookie reliever Doc Hamann was so nervous when he was thrust into his first and only Major League game that he never got a single batter out. With the Indians trailing the visiting Boston Red Sox 9–5, Hamann entered the game in the top of the ninth inning. Unfortunately, he couldn't find the strike zone with a road map. Shaking like a motherless pup, the 22-year-old hurler walked the first two batters he faced, Johnny Mitchell and Ed Chaplin. Then Hamann beaned the next batter, pitcher Jack Quinn, to load the bases. Hamann became more frazzled and walked Mike Menosky, forcing in a run. The young pitcher finally got the ball over the plate, only to watch Elmer Miller blast it for a bases-clearing triple. After giving up a run-scoring single to George Burns, the rattled rookie uncorked a wild pitch and then yielded another RBI single to Del Pratt, which made the score 15–5. Cleveland manager Tris Speaker had seen more than enough. He mercifully yanked Hamann, who never played in the Majors again. The stats for his entire pitching career: three hits, three walks, six runs, one wild pitch, and one hit batsman . . . and an ERA of infinity. Although he pitched in only one game, Hamann left a dubious mark in Major League history: the most batters faced in a career without getting anyone out. Pitcher · Cleveland, AL · September 21, 1922 Just Missed .400

Bill Francis, "Padgett Catches a Glimpse of History for 1939 Cardinals," Inside Pitch: The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum's Weekly e-Newsletter, August 26, 2019

What made Padgett's 1939 season even more exceptional was the fact that that Cardinals were attempting to convert the former outfielder to catcher – though he had never caught prior to that time. "I'd say," said Cardinals manager Ray Blades in July 1939, "that Don really has made progress. He has become a good receiver and he uses pretty good judgment in calling pitches. His worst drawback right now is that he doesn't get the ball away fast enough in throwing to the bases. The reason, of course, is that he isn't used to wearing the harness. His arm is strong enough and pretty accurate but the heavy pads are cumbersome and annoying to one who once was an outfielder."    L-R: Don Padgett, Joe Medwick, Johnny Mize, Enos Slaughter The next day a bewildered Padgett received a letter from Rickey informing him he would be attempting to become a catcher the following spring. "We've got more outfielders than we need … Unless you turn to catching, I'm afraid we'll have to send you back to Columbus. But you're going to be a catcher – a great catcher." Despite his struggles adapting to the tools of ignorance, Padgett was always able to wield a potent bat from the left side of the plate. The husky redhead, known for being genial and affable, broke into the big leagues in 1937 with a .314 batting average, 10 home runs and 74 RBI, then followed it up by hitting .271 with eight homers and 65 runs knocked in. With expectations that Padgett would be the starting catcher in 1939, as the Cards wanted more offense out of the catching position and Slaughter was coming up from the minors to play the outfield, a mid-March injury forestalled those plans for a while. Padgett suffered a dislocated left shoulder as he slipped and fell rounding second base in a Spring Training exhibition against the Reds and would be lost to his club for a month. But when Padgett, 27, returned to the regular season lineup he made up for lost time. Despite losing the starting catcher job to Mickey Owen – infamous a few seasons later for his dropped third strike for the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1941 World Series – Padgett's batting average crept over .400 in mid-June and remained there pretty much until the end of the season. By early August, newspapers across the country were reporting National League managers' bewilderment as to why the Cardinals did not play Padgett – who was batting well over .400 in a part-time role behind the plate at the time – more often back in the outfield. "Padgett is too much for us," said New York Giants manager Bill Terry. "We can handle Joe Medwick pretty well this year and Johnny Mize hurts us like he always did. But Padgett gives us the worst time of all. Early in the season I had my pitchers throwing fastballs to Padgett. We had to stop that before somebody was killed by the line drives he hit. "During our last visit in St. Louis we talked it over and I finally said, ‘Pitch him curveballs. Make him hit a curve.' Padgett came up to pinch hit with the bases full and we threw him curves. On about the second one he decided to swing. And although it was a good curve, he hit it clear over the right field pavilion. Now we'll throw him slow stuff. At least he'll have to use his own power to get distance." Prior to the start of the 1939 World Series, pitcher and NL MVP Bucky Walters of the Reds, who led his team to the Senior Circuit pennant with a 27-11 record, said of Padgett: "He's one guy who made it hard for me. I was wrong most every time I pitched. Padgett made me more uncomfortable than did his teammates, Johnny Mize, Joe Medwick and Enos Slaughter." With the season coming to an end, Padgett dipped below .400 for the first time in months when he went 1-for-4 on Sept. 28. On the penultimate day of the regular season, Padgett didn't play in either game of a doubleheader. Then, in the Cardinals' final game of the 1939 regular season on Oct. 1, Padgett, with a .399 batting average, walked in a pinch-hitting appearance, dashing any hopes of ending his noteworthy year with the coveted .400 milestone. If Padgett had played in eight more games in 1939 he would have qualified for the batting crown, which was then based on participation in 100 or more contests. Padgett later went into the Navy in 1942 and missed four years of baseball while in the military. ... "I spent 10 months at Brisbane, Australia, where the folks were real friendly, and they knew just a little about baseball. Where they were baseball daffy was in the Philippines. I had quite a stretch around Luzon. Altogether, my overseas service lasted 21 months." Padgett spent eight years in the big leagues (1937-41, 1946-48) spending time with the Cardinals, Brooklyn Dodgers, Boston Braves and Philadelphia Phillies, his career ending with a .288 batting average. Padgett died on Dec, 2, 1980 at the age of 68 in High Point, N.C. Vexatious Veecks - II

Bill Veeck: Baseball's Greatest Maverick, Paul Dickson (2012)

Bill Veeck Jr. worked for the Cubs after his father, the GM, died. He was involved in installing the ivy on the outfield walls plus contributing many other ideas to promote the club and increase attendance. In 1942, he purchased the AAA Milwaukee Brewers, a dying franchise with meager attendance.

Fruit and vegetable nights followed. A lady fan who won a basket of peaches returned several nights later with an oversized peach pie, which she presented to Veeck, who spoke about it for months to come. During livestock nights the prizes included turkeys, geese, rabbits, and pigs that often "escaped" onto the field, with the winners expected to chase them. The pigs, needless to say, were greased. One night, the fans were surprised to see an old, swaybacked draft horse on the field awaiting presentation to a lucky fan. The perplexed winner had no idea what to do with the animal, so he was advised to sell it back to the farm from which Veeck had purchased it, allowing the fan to pocket $15.

At one game Veeck awarded a man two pigeons. "I can see that poor guy yet," Veeck recalled later, "sitting there during the game, a pigeon in each hand. He couldn't let go and nobody would help him. And you know pigeons!" Other promotions - free lunches, vaudeville acts, swing bands - helped keep the turnstiles turning during the season. On June 2, Veeck assembled a band made up of players and Milwaukee front office personnel, which included Veeck playing a cheap whistle, [Manager Charlie] Grimm on banjo, and Rudie Schaffer [Veeck's assistant] playing a bass created from a three-gallon paint can, a broomstick, and a well-rosined cord. That an owner would be part of a serenade to his fans was big news: "Cafe de Veeck Wows 'Em in Milwaukee" was the headline in the Chicago Tribune. Veeck created even more publicity when he placed a chicken-wire screen above the right-field fence to turn opponents' home runs into singles. It was then rolled out of the way when the home team came up. The practice was immediately banned. Decades later when Veeck was serving as a friendly witness in Curt Flood's 1970 lawsuit against major-league baseball, its lawyers used the moveable fence to question Veeck's character. "May I say about the fences, as a prelude, that at that time there were no rules forbidding the motion of fences because ... I have tried always not to break any rules, but to test highly their elasticity, and I did put into Milwaukee a moveable fence that was on top of our normal 25-foot right field fence. Since I had more right-hand hitters, I put it in right field, made out of chicken wire and connected to a cable that was operated by a steam winch, and I did pull it out between innings when the opposition was batting and on the next day they had a league meeting and they declared it illegal, immoral, and I stopped." Veeck later applied his promotional ideas as owner of the Cleveland Indians, St. Louis Browns, and Chicago White Sox. The Asterisk Record

"Maris and Ruth: Was the Season Games Differential the Primary Issue?"

Brian Marshall, Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2020 The 1961 season will always be remembered as the year that Roger Maris of the New York Yankees hit 61 home runs to set a new single-season home run record. It was a monumental achievement by Maris at the time ...

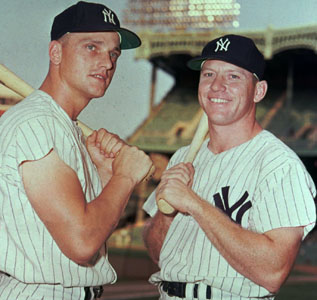

It was an expansion year in the American League. The Washington Senators moved to Minnesota to become the Twins, and new franchises were formed in Washington and Los Angeles to bring the league's team count to ten. To accommodate the additional squads, the schedule was increased to 162 games. ... As the 1961 season progressed it became apparent that two New York Yankees, Maris and Mickey Mantle, were going to go head to head for the home run title, not just for that season, but for all time. The Maris/Mantle home run battle and the nominal eight game differential stimulated MLB Commissioner Ford C. Frick to make the following ruling on July 17, 1961: Any player who may hit more than sixty home runs during his club's first 154 games would be recognized as having established a new record. However if the player does not hit more than sixty until after the club has played 154 games, there would have to be some distinctive mark in the record books to show that Babe Ruth's record was set under a 154-game schedule and the total of more than sixty was compiled while a 162-game was in effect.

There were two problems, and one issue, with the Frick ruling that apparently were unbeknownst to him at the time of the ruling. The first major problem was that the wording "some distinctive mark" did not define what the distinctive mark would be ...The second major problem was that Frick created a situation where the fans would be focused on the first 154 games with great anticipation and meaning and the remaining eight games would effectively be rendered less meaningful. ... Then there was the issue that Frick considered himself a friend of Ruth's. As a sportswriter for the New York American newspapers, Frick had covered the Yankees beginning in 1922. He also had been a ghost writer for Babe Ruth's newspaper columns. ...    L-R: Babe Ruth 1927, Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle 1961, Ford Frick Maris's final three home runs were hit after the 154th game, but for each of home runs number 59 and 60, Maris hit them when he'd had fewer plate appearances than Ruth. ... There were three games during the 1961 season when Maris did not record any plate appearances: May 22, July 29, and September 27. Maris was in the lineup for the May 22 game at Yankee Stadium and took his position in RF, but he came out due to an eye irritation. ... Maris was only in the game for a few minutes during the top of the first inning and never made a plate appearance in the game. For the game on July 29, Maris was never in the lineup because he was sidelined with a pulled muscle in his left leg. On September 27, Maris was given the day off. ... When the final official AL batting statistics were released for publication by MLB on December 17, 1961, there was no asterisk nor any other mark/indication associated with Maris's statistics. Remember that at the time when Maris hit his 59th home run, the asterisk had seemed assured ... Frick maintained that he never stated there should be an asterisk, saying: "As for that star or asterisk business, I don't know how that cropped up or was attributed to me, because I never said it." Frick effectively was his own worst enemy in the asterisk matter. However, after all the dust had settled, the official AL statistics didn't include a mark beside Maris's feat. Down the road, any baseball historian or researcher would know and understand there was a different in the number of AL games in the 1927 and 1961 seasons because it is low-hanging fruit. Less obvious is the fact that Maris had fewer opportunities per game on average, and ultimately hit his record tying 60th home run in three fewer PAs than Ruth. Rusty Staub

Craig Muder,

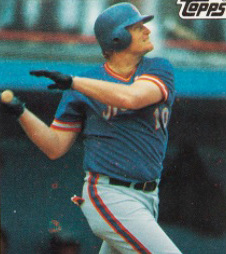

Card Corner Series, baseballhall.org (August 2020) From his big league debut at the age of 19 to his later playing years as one of the game's deluxe pinch-hitters, Rusty Staub could put the bat on the ball. That skill kept Staub in the big leagues for 23 seasons and made him a fan-favorite throughout the game. Staub's 1984 Topps card came out on the heels of his age-39 season when he appeared in 104 games with the Mets – only 10 of which came in the field. But Staub's ability as a pinch-hitter more than made up for his lack of range at either first base or the corner outfield spots.

Born April 1, 1944, in New Orleans, La., Staub was signed as an amateur free agent with Houston in 1961 after a high school career that featured Ted Williams calling Staub one of the best young hitters he ever saw. He signed for a reported bonus of $125,000 and was expected to be the cornerstone of the franchise, which would begin play in 1962. Staub made his big league debut with Houston eight days after his 19th birthday. He played in 150 games as a rookie in 1963 – setting a single-season games-played record for teenagers (including only games played before a player's 20th birthday). Staub was returned to the minor leagues for part of the 1964 season, but became a regular again in 1965 and gained national attention in 1966, hitting .280 with 13 homers and 81 RBI while finishing 22nd in the National League Most Valuable Player voting. The next season, Staub cashed in on his enormous potential by hitting .333 with an NL-best 44 doubles, 10 homers and 74 RBI while earning his first All-Star Game selection. He hit .291 in 1968, the ninth-best average in the NL during the Year of the Pitcher. But the Astros finished last in the 10-team NL in 1968, prompting general manager Spec Richardson to trade Staub to the expansion Montreal Expos on Jan. 22, 1969, for Jesus Alou and Donn Clendenon, both of whom had been selected by the Expos in the Expansion Draft. Clendenon eventually refused to report to Houston, so the Expos later sent Jack Billingham, Skip Guinn and $100,000 to complete the trade. "It was the toughest decision I've ever made in baseball," Richardson told United Press International.

In Montreal, Staub became a folk hero in Canada as "Le Grand Orange" – the first baseball star north of the border. He was named to the All-Star team in each of his three seasons with Montreal, averaging 26 homers and 90 RBI with a .296 batting average in his three seasons with the Expos.

But Montreal averaged 96 losses a season in Staub's time there. Needing young players to build a franchise, the Expos traded Staub to the Mets on April 5, 1972, for highly touted prospects Tim Foli, Mike Jorgensen and Ken Singleton. The deal occurred on the same day the Mets named Yogi Berra to replace Gil Hodges – who had passed away three days earlier – as manager. "I was totally shocked," Staub told the Montreal Gazette following the trade. "I regret having to leave Montreal." But Staub would quickly find a home in New York. After missing more than half of the 1972 season due to a right hand injury, Staub hit .279 with 76 RBI to lead the Mets to the 1973 NL pennant. In the World Series, Staub hit .423 with a homer and six RBI in the Mets' seven-game loss to the A's. After slumping to a .258 batting average in 1974, Staub bounced back with a .282 mark in 1975, which included 19 home runs and 105 RBI – the first time he had cracked the century mark in his career. Then at the Winter Meetings following the 1975 season, the Mets sent Staub and pitcher Bill Laxton to the Tigers in exchange for former World Series hero Mickey Lolich and outfielder Billy Baldwin. Staub spent most of the 1976 season as the Tigers' right fielder, hitting .299 with 15 homers and 96 RBI while earning his sixth-and-final All-Star Game selection. Then in 1977, the 33-year-old Staub became Detroit's designated hitter – a position where he would play 318 of his 320 games over the next two seasons. He averaged 23 home runs and 111 RBI per season over those two years, winning the Designated Hitter of the Year Award in 1978. Traded back to the Expos on July 20, 1979, as Montreal chased a postseason berth, Staub hit .267 in 38 games before he was traded to the Rangers for Chris Smith and LaRue Washington 11 days before the start of the 1980 season. Staub hit .300 in 109 games that season, then signed with the Mets for three years and $1 million as a free agent prior to the 1981 campaign. He would play the final five seasons of his career in New York, primarily as a pinch-hitter. In 1983, he set big league records (since broken) with most pinch-hit at-bats (81) and walks (11). He also set a record with eight straight pinch-hits that season, tying the mark set by Dave Philley in 1958. For his career, Staub had 100 career pinch-hits – good for a .280 average. "Our pitchers don't like to face Rusty, and I don't know many who do," said future Hall of Fame manager Whitey Herzog during Staub's playing days. "He's there with the singles and doubles and hits the ball where it's pitched to." Staub retired after the 1985 season with a .279 average, 2,716 hits, 292 home runs and 1,466 RBI. He appeared in at least 150 games in 12 seasons, and his 2,951 big league games ranked in the Top 10 all-time at the time of his retirement. Staub passed away on March 29, 2018. "He has his place in Met lore," former teammate Keith Hernandez told the New York Daily News on the day following Staub's passing, "and also this city." Personal Note: My biggest claim to fame as a baseball player was that I got Rusty Staub out the one time I faced him. It was the 16-year-old summer league on the diamond at Marconi and Harrison in City Park. Rusty was 13 but right at home with 16-year-olds. His team was clobbering us. So I was called in from third base to the mound in the late innings. With no fences, the playing field between two streets was like the old Polo Grounds - short in right and left fields but with nothing in center field except the backstop of the next diamond. Our centerfielder was playing in the next zipcode when Rusty drove my fastball high in the air to deep centerfield. The runner on third scored easily; so it didn't count as an official at-bat. But I got Rusty Staub out!

The Forgotten Strike: 1972

Jim Gilstrap, Cardinals Gameday Magazine,

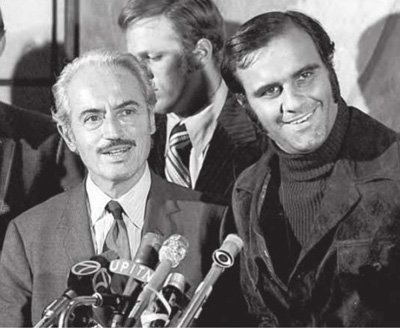

(2020 Issue 2) What shortened the season: The first major league players strike shut down the sport April 1 - just four days before Opening Day - and led to the cancellation of games through April 14.

Players had walked out near the end of spring training, demanding that owners increase contributions to their pension fund and cover higher premiums on their medical insurance. Owners argued that their contribution of $5.45 million annually (from World Series TV revenue) was more than generous, especially because they were paying players higher salaries. "I wouldn't give 'em a damn cent more," Cardinals president Gussie Busch declared before the strike. "They (the players) are going to ruin baseball, the way they're going. I intend to stand up to them." The standoff ended just short of two weeks. Players got less than they wanted for the pension ($500,000 instead of $800000) but negotiated more for their health care fund ($490,000 vs. an initial offer of zero). The final questions: Would the games be made up and would the players be paid for them? The answers: no. The strike cost each club an estimated $200,000 in lost revenue and each player 4.9 percent of his annual salary.   L: August Busch; R: Marvin Miller and Joe Torre announce end of players strike. Luckily for Torre, a crowd of only 7,808 showed up that day at Busch - a statement in itself. Fearful that fans would be angry, the Cardinals scrapped their traditional Opening Day pregame ceremonies. By June 1, the club was 14 1/2 games out of first and dead last in the NL East - another sore point for fans. They recognized a veteran-heavy roster hadn't stayed together during the strike and worked out as a unit the way some clubs had. The Cardinals did climb into third place in July, but after winning 90 games and finishing second in 1971, the '72 team's final ledger (75-81, fourth place) did little for ticket sales. An average attendance of 15,544 per game remains the club's second-lowest since moving downtown in 1966. It could be argued the prospect of a strike along with players demanding bigger salaries, both sore subjects with Busch, derailed not only the 1972 season but the rest of the decade. As talk of a strike grew, Busch reacted to contract holdouts by 20-game winner Steve Carlton and promising lefty Jerry Reuss by ordering them traded. Carlton, dealt in February, would go on to win four Cy Young Awards, 329 games and land in the Hall of Fame. Reuss, traded on Opening Day, pitched in the majors for 22 seasons and won 220 games. "At that game, Gussie Busch wasn't going to have anyone dictate policy to him," said Torre, who also was a holdout that spring. "Over a couple of months, he traded both 'Lefty' and Reuss. That sort of neutered our pitching staff." Bottom line for baseball: Perhaps the Boston Red Sox suffered the cruelest fate. Because the schedule picked up April 15, not all teams played an equal number of games. Boston played one fewer than Detroit - and lost the AL East by a half game to the Tigers. The Oakland A's ... would defeat the Reds to win their first of three straight World Series. He said it: "Once the strike came around, that really turned him off. We were the only club in which the players were able to room by ourselves, without it costing us anything. There were a lot of little things about playing for the Cardinals like that, things he was responsible for, that made it special. I think, as well as he treated the players, he felt he deserved more than that. And I didn't disagree with him." Torre, on why he sensed Busch never felt the same about the players after the strike. |

CONTENTS If the Cubs threw the 1918 World Series,

|