|

July 9, 1915 - Comedy of Errors

SABR Games Project, sabr.org, Warren Corbett

The 1915 Cleveland Indians, in their first year with that nickname after Napoleon Lajoie retired, were a woeful team with a near-bankrupt owner. They were in last place on July 19 when they made unwanted history as they lost their fifth straight to the Washington Senators, 11-4. Washington ran away with eight stolen bases in the first inning, still the major-league record — though it is a tainted one.

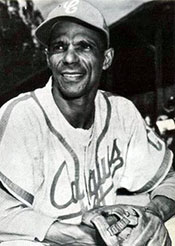

The Senators, who were on the fringe of the pennant race tied for fourth place, started their nonpareil, Walter Johnson at League Park in Cleveland, against a right-hander decorated with the name Zerah Zequiel Hagerman, who preferred to be called "Rip" for obvious reasons. Hagerman was a lanky Kansas farm boy like Johnson, but the resemblance ended there. Hagerman opened the top of the first by walking Washington leadoff man Danny Moeller. After Eddie Foster flied out, Moeller took second on a balk. By the rules of the time, he was credited with a stolen base; it is not a steal today. (The scoring rule was changed in 1955.) Clyde Milan walked, and he and Moeller executed a double steal. When Cleveland catcher Steve O'Neill threw to second, Milan got into a rundown while Moeller kept going around third to score, credited with two steals on the play. Milan escaped the pickle to complete a successful theft of second. Hagerman doled out his third walk, to Howie Shanks. Then the pitcher, asleep or shell-shocked, held the ball while Milan swiped third. Chick Gandil delivered Washington's first hit, a triple to left-center that brought home Milan and Shanks. Cleveland LF Jack Graney's poor throw allowed Gandil to score as well. At this point manager Lee Fohl mercifully relieved Hagerman, who had been ripped for four runs on one hit, three walks, an error, and five stolen bases.     L-R: Rip Hagerman, Walter Johnson, Steve O'Neill, George McBride The official scorer ruled the Little League play a double steal, Washington's seventh and eighth thefts of the inning, with the Indians' third and fourth errors charged to Indians and Indians. Indians, the Senators' ninth batter, flied out to end the farce. Johnson walked to the mound with a 6-0 lead. The "King of Pitchers" had roiled the baseball world in the offseason when he signed with Chicago of the outlaw Federal League, then turned around and re-signed with Washington. White Sox owner Charles Comiskey had kicked in $6,000 to sweeten the Senators' offer and keep Johnson from joining the rival Chicago club. Pitching just 18 days after the birth of his first child, Walter Jr., Johnson knew what to do with a big lead: He coasted. "Johnson didn't exert himself in the least — he just shoved the ball over the pan and let the Indians hit it," the Cleveland Leader's Charles W. Swan wrote. Cleveland managed only two singles in six innings while the Senators built their lead to 8-0. Assured of his 15th win, Johnson retired to rest his arm. Indicative of his effort, he did not strike out a single batter for the only time in any of his starts that season What's Old Is New Again

Sports Illustrated Spring 2020, Jack Dickey

Thomas Marshall, Woodrow Wilson's vice president, threw out the first pitch at the Washington Senators' home opener against Boston; the Indians, behind CF Tris Speaker, got off to a 33-16 start. Yet it inaugurated a decade that remains one of the game's most memorable and dynamic.

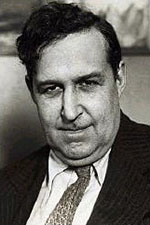

Small ball gave way to slugging. Total attendance, which had cleared 7 million just twice before, exceeded 9 million in seven of 10 seasons. Lou Gehrig, Paul Waner and Lefty Grove started their careers; Speaker, Ty Cobb and Walter Johnson ended theirs. And the lowly Yankees, stirred to life by their purchase of Babe Ruth just five days into the decade, opened Yankee Stadium and won six pennants and three World Series, en route to becoming the sport's signature franchise.Any history-minded baseball nut (which is to say, any baseball nut) would likely recall the 1920s here in 2020, round numbers being what they are. But the resonance between those '20s and our '20s doubled with MLB's substantiation, in mid-January, of the extensive sign-stealing operation the Astros used during their '17 title run. The reason there is a commissioner of baseball to investigate and sanction Houston dates to the revelation, in 1920, that the 1919 World Series had been fixed for gamblers' benefit. As with the Astros, a year's worth of whispers preceded a formal probe. (After his heavily favored team lost the best-of-nine World Series 5-3 to the Reds, White Sox owner Charlie Comiskey offered a $20,000 bounty, nearly $300,000 in today's money, to anyone with evidence of malfeasance.) Conducting the inquiry was a grand jury in Cook County, Ill., which had been convened to investigate game-fixing in baseball and then spent the final stretch of the 1920 pennant race hauling various stars before it. Billy Maharg, a gambler and onetime replacement player for the Tigers and Phillies, served as the scandal's Mike Fiers, telling all to the Philadelphia North American, and days later Sox righty Eddie Cicotte spilled to the grand jury. Though none of Chicago's so-called Eight Men Out was ever convicted of a crime, new commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis banned them all for life in August '21.    L-R: Charlie Comiskey, Eddie Cicotte, Kenesaw Mountain Landis The first - obvious, one would think, though it has eluded the commissioner - goes to the merits of decisive action against cheaters. Manfred slapped the Astros with a $5 million fine, stripped them of four draft picks and suspended G.M. Jeff Luhnow and manager A.J. Hinch. But his choice to release only a sliver of the evidence and offer Houston's players blanket immunity in exchange for their testimony nurtures suspicion and damns the cheaters, who, unpunished, are unable to pay their debt to baseball. The second, and, again, Q.E.D.: Give the people who play and coach and think about this game the space to do what they do best and they can lift baseball from the mire of scandal to exciting new heights. Run out of Brooklyn

Michael Lynch, Baseball's Untold History: The World Series (2016)

Hall of Fame hurler Rube Marquard was run out of Brooklyn after a run-in with the law during the 1920 World Series.

Although his best years were behind him, 33-year-old 13-year veteran lefty Rube Marquard helped the Brooklyn Robins win the National League pennant in 1920 when he went 10-7 with a 3.23 ERA in 28 games. He started the first game of the World Series against the Cleveland Indians and lost 3-1, allowing all three runs in only six innings of work. Then he tossed three scoreless innings in relief in Game Four, a 5-1 Brooklyn loss. They would prove to be the last frames Marquard would throw in the postseason. Prior to Game Four the southpaw was arrested in the lobby of the Hotel Winton in Cleveland when he was caught trying to scalp tickets, a set of box seats with a face value of $52.80 for which Marquard paid $275 and was asking $350. Marquard was released on his own recognizance and ordered to appear in court the following Monday. "The police say that they would have held him in custody if it had not been for the fact that they did not want to be accused of trying to cripple the Brooklyn club while it is playing in the world's series here," reported the New York Times.    L-R: Rube Marquard, Wilbert Robinson, Charles Ebbets The Indians wrapped up the best-of-eight Series with a 3-0 win in Game Seven on October 12, and Marquard was found guilty of ticket scalping and incurred a $1 fine and costs, making his total fine $3.80. The judge was lenient because he felt the negative press Marquard received was punishment enough. But Marquard was persona non grata as far as Brooklyn owner Charles Ebbets was concerned. "I'm through with him absolutely," Ebbets spat. "He hasn't been released, however, and if anyone else wants him he can have him. But Marquard will never again put on a Brooklyn uniform." Neither Heydler nor the National Commission took further action, although it was speculated that Marquard would be "railroaded" out of the National League. To add insult to injury, Marquard's wife, Vaudeville star Blossom Seeley, asked for a divorce on October 15 on the grounds that Marquard had deserted her in 1918. Once the smoke cleared and the dust settled, Marquard was traded to the Cincinnati Reds on December 15, 1920 for pitcher Dutch Ruether. He spent only a year with the Reds, then pitched for the Boston Braves from 1922-1925 before calling it a career. He went 201-177 with a 3.08 ERA in 18 seasons and was inducted into the Hall of Fame by the Veteran's Committee in 1971. Editor's note: What Lynch fails to mention is that baseball had just gone through the Black Sox Scandal, which exploded onto the nation's front pages with the Chicago Grand Jury's investigation into charges that the White Sox threw the 1919 Fall Classic. So Marquard couldn't have picked a worse time to make money off of scalping World Series tickets. A Win for Equality

John Rosengren, Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the Hall of Fame

(Opening Day 2020) In 1925 in Wichita, Kansas, an African-American team defeated a team sponsored by the Ku Klux Klan. Members of the Ku Klux Klan possessed undeniable power throughout the early years of the 20th century - their anonymity secured by hoods and their actions backed by local law enforcement.

But on a Sunday afternoon n the first day of summer in 1925, the Klan suffered defeat at the hands of a group of African Americans armed with baseball bats. And gloves. The loss occurred on a baseball diamond, Island Park to be specific, in Wichita, Kan., on June 21, 1925, when the all-black Wichita Moravians - a barnstorming team - played a game against the KKK nine of Lodge No. 6. The Monrovians, who had played two previous seasons independently as the Black Wonders, joined eight other teams from Nebraska, Missouri, and Kansas in 1922 to form the Colored Western League. The Monrovians took their name from the capital of Liberia, founded in part by former slaves who had known the Klan's terror. ... The Monrovians won the pennant in the Colored Western League's debut season, but that would be its only season. The league, troubled by financial challenges and infighting among team leaders, folded after one year. But the Monrovians survived. The team was owned and operated by the Monrovian Corporation, whose capital stock was valued at $10,000. Run by a collection of African-American businessmen, it was a healthy enterprise. The Monrovians owned their ballpark in the heart of Wichita's African-American neighborhood, which put them in charge of their schedule and in receipt of the gate - unheard of for ballclubs like theirs. The team and its success - in 1923, they were 52-8 - became a rallying point and diversion for Wichita's 6,500 African Americans, a fifth of whom lived in poverty and all of whom lived under Jim Crow conditions. Although Kansas had entered the Union 64 years earlier as a free state, in 1925 racial segregation still ruled. African Americans in Wichita could not order a sandwich at the Dockum Drug Store ... Visiting black players could only stay in hotels designated for "coloreds." And at the movie theater, designated black sections reserved the best seats for white patrons. ...  Island Park Stadium, Wichita KS The Ku Klux Klan contributed to the persecution. Since its revival in 1915, the organization had grown in a decade to four million members nationwide, with an estimated 40,000 of those in Kansas and 6,000 in Wichita - almost one Klan member for every African American. Knights of the KKK were embedded in nearly every institution, from city governments to banks. Membership was so widespread that even Tom Baird, co-owner of the Kansas City Monarchs, joined the Klan. ... William Allen White, editor of the Emporia Gazette, ran for governor in 1924 on an anti-Klan platform, calling out the secret society's campaign of terror and branding its members a "body of moral idiots." White lost his bid, but sentiment against the Klan had taken root. The Kansas Supreme Court ruled in January 1925 that the Klan was a sales organization - not a charitable entity - and barred it from doing business without a charter. The state turned down the Klan's application for a charter on June 3, 1925. The Klan, which had tried to promote itself as good for society by donating money to the local hospital and giving away food baskets to needy families, faced extinction in the state. Desperate to preserve itself, it may very well have agreed to play the all-black Monrovian team as a public relations ploy. "On some level, it was a matter of proving superiority," said Donna Rae Pearson, a Topekan librarian who researched the game for the Kansas State Historical Society. "The Klan figured, 'We're going to beat you because we're superior beings.'" The Monrovians certainly had their pride at stake, but their motivation was probably mostly financial. Their games against white teams always drew well, but a matchup against the Klan promise a large gate. They solicited their fans to attend the game to be played at the white ballpark on the point of Ackerman Island in the Arkansas River. "There was racial pride on the line, but also money to be made," Dixon said. The Wichita Beacon announced: "Strangle holds, razors, horsewhips and other violent implements of argument will be barred at the baseball game" - perhaps tongue in cheek, but, even still, such a comment hinted at the possibility of violence in the charged atmosphere between opponents of such extremities. To keep the game under control, the teams agreed to an impartial pair of umpires: "Irish" Garrety and Dan Dwyer, both white and Roman Catholic.  Members of the Wichita Monrovians A heat wave driven by scalding winds and a temperature topping 100 degrees could not keep away the large number of fans of all races who filled Island Park - far more than attended the other three baseball games played elsewhere that day in Wichita. The tension throughout the first half of the game soared as high as the mercury, with the score tied, 1-1, through five innings. Perhaps the heat wilted the pitchers, because the game soon turned into an explosion of runs, the lead going back and forth - the fate of the two teams and their fans hanging in the balance - until the Monrovians won, 10-8. The Monrovians' victory did not eradicate prejudice or eliminate segregation, but for one day at the ballpark, the black community could exalt in finishing on top. And, in the days that followed, the Monrovians could take pride in the fact that they had done their own part in ushering the Klan out of Kansas and cleansing the state of the organization's unbridled bigotry. Vexatious Veecks - I

Bill Veeck: Baseball's Greatest Maverick, Paul Dickson (2012)

Shortly after persuading recalcitrant NL and AL owners to support the playing of the first All-Star Game in 1933, Bill Veeck Sr., General Manager of the Chicago Cubs, proposed another radical idea.

Calling these weeks the game's "dog days," Veeck urged their monotony be broken with interleague games that counted in the standings. Veeck's plan was quite specific: thirty-two interleague games for each club, with four against each team of other league - two home and two away.

Gould's story appeared in every major city. The reaction to what the Chicago Daily News called a "radical prescription" was immediate. Cleveland Indians president Alva Bradley and Brooklyn Dodgers president Stephen W. McKeever had declared themselves definitely in favor of the idea, and the Cardinals' Sam Breadon and the Pirates' William Benswanger felt it was worth considering. Soon though, the "Veeck Plan," as it was known, was attracting serious American League opposition. Opined Clark Griffith, the gray-haired president of the Washington Senators, "Nobody thinks of that sort of stuff unless he's deaf, dumb, and blind." Col. Jacob Ruppert, the owner of the Yankees, dismissed the notion, saying he had not given it "a single thought." The American League believed itself the superior circuit and did not want to share the box office draw of Ruth, Gehrig, and others.  Tetelo Vargas Pollock based his argument on having sent his Cuban Stars to play in thirty-two states during the previous season, in the process beating every white minor-league team they faced. He wrote about one of his stars, Tetelo Vargas, who he predicted would steal more bases during the season than any two current major-league players combined. Vargas had also hit seven consecutive home runs in two days against top semipro competition in 1931, but this feat was entirely ignored by the white press. "With a colored club in either or both circuits, these feats, common among colored ballplayers, would not go unnoticed and bring greater interest in baseball, with the necessary publicity to go with it."

To bolster his argument, Pollock quoted Babe Ruth's comment that "the colorfulness of Negroes in baseball and their sparkling brilliancy on the field would have a tendency to increase attendance at games," [and] Pirates coach Honus Wagner's assertion that "the good colored clubs played just as good as seen anywhere" ... The letter ended with the assurance that Pollock was in a position to assemble such a team or teams for the 1934 season. ... Pollock sent a copy of the letter to the local North Tarrytown Daily News, which published it the day after it was mailed to Veeck. In due course, it was picked up by the Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier, Amsterdam News, and other Negro newspapers. Whether Veeck had any thoughts of acting on the idea of a black team or teams in the majors is unknown. No surviving record exists of a response by Veeck to Pollock, which is most likely explained by the fact that Veeck was suffering the early stages of the illness [leukemia] that would take his life. A Radical Proposal

Bill Veeck: Baseball's Greatest Maverick, Paul Dickson (2012)

The Great Depression had a devastating effect on Major League Baseball just as it had on all of American society. That effect caused some to offer unheard proposals.

On February 5, 1933, ... the grand ballroom of New York City's Commodore Hotel hosted more than 600 of the game's leaders ... and all the National League officials in town for their annual meeting - at the tenth annual New York Baseball Writers' Association of America dinner. It was a night of fun, frolic, and frivolity. Sportswriters took turns spoofing everyone from the guest of honor, retired New York Giants manager John McGraw, to the New York Yankees, who had won the World Series in October. In addition, the scribes performed their annual blackface minstrel show in front of the predominantly white crowd. New York Times sportswriter John Drebinger in his column the next day called the minstrel show the most entertaining part of the evening but never mentioned its most dramatic moment. Heywood Broun, a talented and outspoken Scripps-Howard columnist who was a syndicated in dozens of newspapers and admired by his fellow writers, offered a full-blown proposal for racially integrating baseball, arguing that the game's falling gate receipts could be reversed by dropping its invisible "color line." Branding baseball's segregation as "silly," Broun asked rhetorically: "Why, in the name of fair play and gate receipts, should professional baseball be so exclusive?" Broun addressed head-on the concern that some players would object to racial integration, but then dismissed it by pointing out that ballplayers objected to many things that still took place with a high degree of regularity, such as fines, suspensions, and the widespread salary cuts being imposed for the upcoming season. Bill Gibson, a writer for the Baltimore Afro-American and one of a handful of writers from the Negro press at the dinner, found a number of people who expressed an open mind on the subject, including Branch Rickey of the St. Louis Cardinals, Yankees slugger Lou Gehrig, and John Heydler, president of the National League.

Major League Baseball would not be integrated until Branch Rickey called up Jackie Robinson to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, 13 years after the incident cited above. The Greatest Cardinal of Them All

"Player of the 1940s Decade: Stan Musial," St. Louis Cardinals 2017 Yearbook

The episodes that mark Stan Musial's performance in the 1940s have filled many pages in many books. He wasn't just the player of the decade for the Cardinals, he was the player of the decade in the National League, and arguably in all of baseball. How he got to be that player was somewhat remarkable. Musial was a hard-throwing lefthanded pitcher growing up in Donora, Pa., so gifted that at 14, he was recruited to play for the semipro Donora Zincs. Standing all of 5-foot-4 and 140 pounds, Musial struck out 13 adult batters in his six-inning debut. No question, Musial could throw hard. He just couldn't be certain where the ball was going. Michael Duda, who coached Musial in his only season of high school baseball at Donora High, recalled the quandary. "The problem with him as a schoolboy pitcher was we couldn't find anyone who could catch him," Duda said. "He might strike out 18 men, but half of them would get to first on dropped third strikes." The good news: Musial had a knack for hitting, too. During that same season at Donora High, he batted. 455 and led the school to the Mon Valley High School championship. Passing up a possible scholarship to play basketball at the University of Pittsburgh, Musial signed a Class D contract with the Cardinals before the 1938 season. In his organizational report on Musial, scout Andrew French wrote: "ARM? ... Good. FIELDING? ... Good. SPEED? ... Fast. Good curve ball. Green Kid. PROSPECT NOW? ... No. PROSPECT LATER? ... Yes." But Musial's transition from suspect to prospect - to Hall of Fame - would include a dramatic change of direction, a shift that blossomed in the 1940s, and began by fate.    L-R: Young Stan Musial at Rochester; Stan and Lillian with their son Dick; One of the most iconic stances in baseball history. Musial was still considered a pitcher by trade in 1940, and seemed to be progressing in Class D Daytona Beach. Manager Dickie Kerr was employing Musial as an outfielder on days he wasn't pitching, an approach that was working well as Musial won 18 games and batted over .300. But in August, Musial was playing in the outfield and hurt his left shoulder diving for a ball.

It was a bad break, probably the best bad break in the history of the franchise. His career as a pitcher would soon be over, and he was not disappointed. "More and more, I wanted to be a hitter," Musial said years later. The die, which would be underlined by 3,630 career hits, was cast. During the same season in which Joe DiMaggio hit safely in 56 consecutive games and Ted Williams batted .406, Stan Musial the hitter was born. In 1941, a 20-year-old Musial batted .379 at Class C Springfield, .326 at Class AA Rochester, and finally .426 in 12 late-season games in St. Louis. During that September promotion, the Cardinals played a doubleheader with the Chicago Cubs in which Musial played left field in the first game and right field in the nightcap. In the first game, he made two diving catches, threw out a runner at the plate and collected four hits. In the nightcap, he stroked two more hits and made two more notable catches. Afterward, Chicago manager Jimmie Wilson offered, "Nobody can be that good. Nobody." But Musial was just getting started. Over the rest of the decade, Musial became the first player in baseball history to win three MVP awards and assumed his place as the National League's dominant gene. He won three batting titles and led the Cardinals to four World Series appearances (1942, '43, '44 and '46) in five years. In fact, the only year the club missed a pennant during that stretch - second-place in 1945 - Musial missed the season serving in the Navy. From 1942 through '49, baseball's "perfect warrior" batted .346 with a .427 on-base percentage and .578 slugging average. He averaged 21 homers, 43 doubles, 100 RBIs and led the league in triples four times, and in doubles and hits five times. "You could scout Musial by the sound of the ball hitting the bat," former teammate Joe Garagiola said. "You didn't even have to watch him." You didn't have to watch him, no. But you couldn't help but watch him. While DiMaggio dated Hollywood starlets and Williams fought battles with the press, Musial was to baseball what Andy was to Mayberry. He married his high school sweetheart, signed countless autographs and represented wholesome values of his Midwestern surroundings. "I remember one spring training I caught him entering the hotel lobby at 7 a.m.," recalled Kerr. "I thought he'd been out all night roaming the town. When I asked him about it, he said, 'No, sir. I'm coming back from morning Mass.'" Bouts with appendicitis and tonsillitis pulled Musial down in 1947, as he "slumped" to a .312 average. He was determined to bounce back in 1948 and changed his batting approach to hit for more power. The result was one of the greatest seasons ever registered by a big-league player. His .376 average won the batting title by 43 points. His .702 slugging average topped the category by 138 points. His 131 RBIs led the league, too, while his home run total (39) fell on shy of Ralph Kiner's and Johnny Mize's 40, denying Musial the Triple Crown. It was the only meaningful offensive category in which Musial did not rank first. Perhaps one game in '48 best underscores the zone in which Musial was operating. The Cardinals were clinging to their pennant hopes when they faced the first-place Boston Braves on Sept. 22 and Stan was dealing with two swollen wrists. Carefully picking his spots, he took only five swings that game. And he went 5-for-5 with a home run, double and two RBIs. It was his fourth five-hit game of the season, tying a record set by Ty Cobb 26 years earlier. The Cardinals didn't catch the Braves that season (not for lack of effort by Musial, who hit .443 against them in 22 games), and they finished one game behind the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1949. A remarkable decade in Cardinals baseball had come to an end, but the legend of "Stan the Man" was just beginning.

In his book Rob Neyer's Big Book of Baseball Legends: The Truth, the Lies, and Everything Else (2008), Rob researched numerous baseball tales to see if he could verify each story from newspaper accounts. Here's two that he concluded were basically true.

Tommy Lasorda & God

Tommy Lasorda told this story that occurred when he was pitching for AAA Montreal in the Dodgers organization.

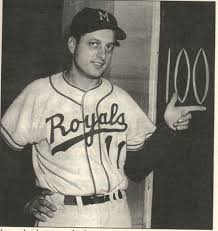

The following Friday I pitched against Buffalo. Because of the problems with (manager) Bryant I desperately wanted to win this game. Late in the game Buffalo loaded the bases with no outs. Bryant was on the top step of the dugout, ready to pull me. In my entire career, I had never prayed on the pitcher's mound, but this time, I turned my back to the hitter, looked up, and thought, Lord, I've never asked you to help me win a game. All I've ever asked was the strength to do the best I could at all times. Lord, I'm in a jam here, and any help you can give me would be greatly appreciated. Suddenly, I heard my name being called. "Lasorda? Lasorda?" It was incredible. I turned around. It was the umpire, Billy Williams. "Come on, Lasorda," he said. "You gotta throw it sometime." "Wait a minute," I told him. "I'm talking to God." "Who?" "God." "Oh," Billy said, as if he understood, then turned around and walked back to home plate. He probably figured I was crazy, but on the one chance I had a direct line... My first pitch was an inside fastball, neither inside enough nor fast enough. The batter jerked it down the left-field line. Our third baseman, George Risley, leaped as high as he could and deflected the ball. It bounced off his glove toward the outfield grass. A base hit, I thought as I ran to back up third base, two runs'll score at least. But our shortstop, Jerry Snyder, dived and backhanded the ball on the fly. Lying on his back, he flipped to second base for the second out, and the second baseman fired to first to complete the triple play. I'd played thirteen summers and eleven winters of professional baseball and had never before been involved in a triple play. As I walked nonchalantly off the field, I looked at Billy Williams, who was staring at me with his mouth open. Then I looked into the sky and said, "Thank you, Lord, but was it really necessary to scare me like that?" That turned out to be the last game I ever pitched...    L-R: Tommy Lasorda, Mel Ott, Ed Brandt Ott Was Ready

Bob Addie wrote the following story in the Washington Times-Herald in 1950. Mel Ott, now a front office executive for the New York Giants, tells an amusing story of the 1933 World Series between the Washington Senators and the Giants. It seems that Senator pitchers went over to scout the Giants one day before the Series began. "I was facing a pitcher named Ed Brandt," Mel recalls, "and he could have gotten me out by throwing basketballs up there. I never could hit him. Well, on this day, the Washington pitchers saw Brandt strike me out twice on inside curves - each time on three pitches, too. Then I popped up twice and grounded out another time. I never did get that ball out of the infield. So the first game of the World Series comes and Walter Stewart, a left-hander, was pitching for Washington. I told myself: 'I'll bet Washington thinks I can't hit an inside curve. I'll take one to see.' Sure enough, the first pitch was an immediate curve for a strike. On the next one, I slammed the ball into the seats for a homer. Nobody threw me an inside curve after that." Baseball Digest, February 1946

Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey

Amazin' Ace

Tom Verducci, Sports Illustrated (October 21-28, 2019)

|

CONTENTS July 9, 1915 - Comedy of Errors The Greatest Cardinal of Them All The Strike-Shortened 1981 Season

|