|

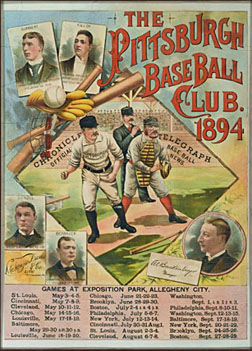

Baseball in 1894

The Emerald Diamond: How the Irish Transformed America's Greatest Pastime,

Charley Rosen (2012) For the most part, the unfolding of an exhibition baseball game played in 1894 between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Kansas City Cowboys would seem almost familiar to modern fans, full as the day was with men in uniform, albeit blousy wool ones, and with green grass, a blue sky, and scores of enthusiastic fans. But then some profoundly unfamiliar playing rules would soon disconcert and confuse the modern onlooker. For example: In the 1800s, the National League was the only universally accepted major league, but there were twenty-five other leagues in North America of varying professional status and stability. Even the NL was financially shaky, so before, after, and even during the season, most clubs sought to increase their revenue by engaging in numerous contests against whichever non-NL teams could offer them acceptable dates. ... That's why the NL's Pirates were in Kansas City's Exposition Park to play a midsummer's contest against the Cowboys, one of the premier teams in the Western League. In fact, seventeen of the Cowboys were either once or future major leaguers.

Behind the plate for Pittsburgh was Connie Mack ... the player-manager ... The Pirates led 8-6 and the Cowboys were batting in the top of the ninth with two outs and runners on second and third. That's when the batter struck a fly ball that bounced just beyond the reach of Pittsburgh's left fielder. One runner scored easily, but the accurate relay to the shortstop and then to Mack was a cinch to beat the tying run to the plate by a large margin.

However, a feisty Irishman named Tim Donahue was the K.C. captain and third-base coach of the moment. As the runner rounded the bag, Donahue took off and ran ahead of him, much like a pulling guard leading a halfback into the line of scrimmage. Taking care to stay on the nether side of the foul line, Donahue plowed into Connie Mack just before the catcher could receive the throw. Mack bounced one way, the ball bounced another way, and the runner was safe at home. Because Donahue never trod on fair territory, his trick was totally legal! Since Connie Mack was famous for his own relentless search to discover exploitable loopholes in the existing rules, he was, however bruised, also quite impressed by Donahue's maneuver. In any event, the run counted and the score was knotted at 8-8 when the Pirates came to bat in the bottom of the ninth. Mack was coaching at third, with a man up and a man on first. The batter smacked a line drive over the third baseman's head that was a sure double. What was uncertain, however, was whether the runner on first could come all the way around to score the winning run. The odds seemed long when the Cowboys' left fielder made a swift recovery and launched a strong throw toward catcher Fred Lake. Indeed, the ball was already in Lake's glove when Mack waved the runner home - then proceeded to barrel down the line in a duplication of Donahue's successful ploy. Mack crashed into Lake with such force that the ball was, deja vu, knocked loose. The umpire on duty signaled that the run counted and the game was over. In a flash, the riotous hometown fans stormed out of the stands and battled the police for control of the field, while Lake turned and punched the ump in the jaw. Thereby concluding what was deemed to be just another exciting day at the ballpark. No matter how violent, marginally legal, or downright illegal an action might be, winning a ball game always justified the means. And early in baseball's history, there was a name for this ruthless game plan. Irish baseball.

The October Heroes: Great World Series Games Remembered by the Men Who Played Them, Donald Honig (1979)

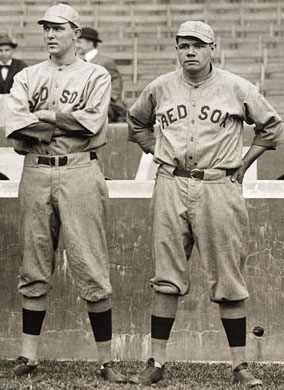

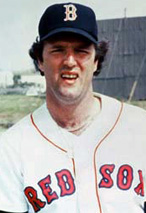

Ernie Shore recounted his most famous game for author Donald Honig.

It was on June 23, 1917, at Fenway Park, against Washington. Babe Ruth actually started the game for us, but he didn't stay in there very long. He walked the first batter, Ray Morgan. Babe didn't approve of some of Brick Owens' ball and strike decisions and let the umpire know about it. Babe got to jawing so much that Owens finally told him to start pitching again or be thrown out of the game. That seemed to set Babe off even more and he said something like, "If I go I'm going to take a sock at you on my way out." Well Owens gave Babe the thumb right then and there. Ruth tried to go after Owens but a few of the boys stopped him, and a good thing too.

When I came back to the bench Barry said to me, "Do you want to finish this game, Ernie?" My ball was breaking very sharply and he had seen that.

"Sure," I said. "Okay," he said. "Go down to the bull pen and warm up." So I did that and came back for the second inning. From then on I don't think I could have worked easier if I'd been sitting in a rocking chair. I don't believe I threw seventy-five pitches that whole game if I threw that many. They just kept hitting it right at somebody. They didn't hit but one ball hard and that was in the ninth inning. John Henry, the catcher, lined one on the nose but right at Duffy Lewis in left field. That was the second out in the ninth. Then Clark Griffith, who was managing Washington, sent a fellow named Mike Menosky in to bat for the pitcher. Griffith was a hard loser, a very hard loser. He didn't want to see me complete that perfect game. So he had Menosky drag a bunt, just to try and break it up. Menosky could run, too. He was fast. He dragged a good bunt past me, but Jack Barry came in and made just a wonderful one-hand stab of the ball, scooped it up and got him at first. That was a good, sharp ending to the game, which I won by a score of 4-0. It wasn't until after the season that they decided to credit me with an official perfect game. There had been a little controversy about it because I had faced just twenty-six men. But they decided to put it in the books as a perfect game and it's been there ever since. I didn't even know I had a no-hitter going, much less a perfect game, until I sat down on the bench in the eighth inning. Then one of the fellows said to me, "Do you know they don't have a hit off of you?" Well, I didn't know. "Maybe they'll get one in the ninth," I said. Then I laughed and said, "And maybe they won't." They didn't.

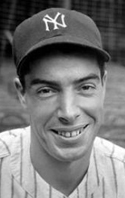

A Legend in the Making: The New York Yankees in 1939, Richard J. Tofel (2002)

Years later, people were still talking about that afternoon. Spud Chandler recalled such a conversation from the early 1950s. I'm sitting in the ball park [in Marysville, Tennessee] with a scout from the Milwaukee Braves. ... Three college kids come in and sit right down beside us. A few minutes later somebody hits a long clout to center field. It was over the center fielder's head, and he turned and ran and made a leaping catch with his back to the playing field. It was a terrific play as far as I'm concerned, as good as you'll ever see. It was the top of the ninth, with the Yankees down by five runs. Chandler had come on in relief ... Earl Averill of the Tigers was on first when Greenberg came to bat with one out. Everyone in the Stadium seems to have had the next few seconds firmly etched in their memory. Tommy Henrich was playing right field, and recalled it this way:

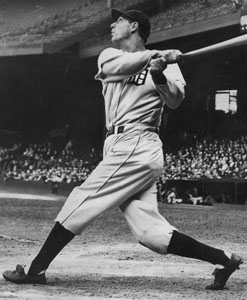

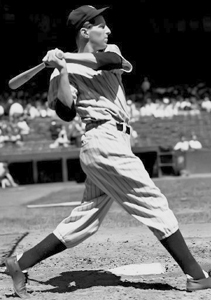

L-R: Spud Chander, Hank Greenberg, Tommy Henrich DiMaggio was modest when he wrote about the moment. But it remained vivid for him as well. He picks up the story from Henrich, noting that the ball had been hit "about 450 feet toward center, directly on a line with the flagpole in front of the Stadium bleachers." He wrote, "As I got to the center field flagpole, I recall seeing the 461-foot sign."

Bobby Feller, having traveled to New York in advance of his Indians, the next team scheduled into the Yankee Stadium, was in the stands with his mother. Feller later remembered that DiMaggio caught the ball with one hand. As Chandler put it, "he just flicked out his hand and caught the ball." Greenberg, the victim of this feat, was less admiring, but also could not forget what had happened. "As I hit it I figure it's going to hit the wall," Greenberg said, "and maybe I can get an inside-the-park home run on it." But he also recalled that DiMaggio

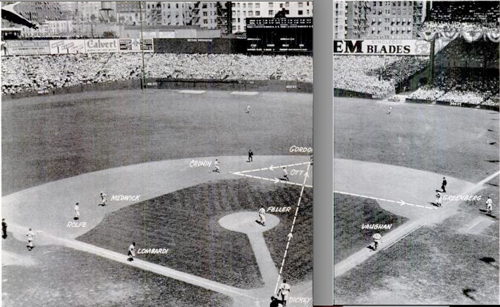

The next day's New York World-Telegram called it "undoubtedly the greatest catch in the history of Yankee Stadium." The more sedate New York Times said it "probably" was. Many years later Henrich called it "the greatest catch I've ever seen." DiMaggio took special pleasure in the moment. In 1937, Tris Speaker, whose mantle as the game's greatest outfielder DiMaggio was threatening to assume, had advised DiMaggio, "There are two things wrong. You're better than you think you are, and you play too deep." But in July 1939, at around the time of the All-Star Game, Speaker had told an interviewer he could name "at least 15 better center fielders than DiMaggio." The catch off Greenberg, DiMaggio later wrote, "coming less than a month after the Speaker story had been blown up all out of proportion, gave me a great deal of personal satisfaction ... I believe it was the best outfield play I ever made."  Yankee Stadium during 1939 All-Star Game; Even the Browns: The Zany, True story of Baseball in the Early Forties,

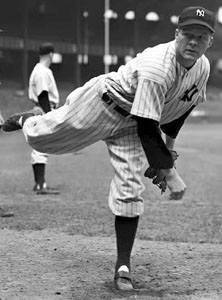

William B. Mead (1978) A game in St. Louis on July 20, 1944. Nelson Potter was pitching for the Browns; Cal Hubbard was umpiring behind the plate. Hubbard:

Nelson was one of the ones they all accused of throwing spitters. I don't know whether he did or not. He was a kind of sidearm pitcher and the ball broke down a little bit. But [licking motion] he'd do that; go to his mouth, see, and that was against the rules. This night ... Hank Borowy was pitching for the Yankees. Every once in a while Borowy would do that [licking motion]. He was just kind of wetting his fingers. He wasn't throwing spitters. But Luke Sewell came out and he said to me, "Make Borowy keep his fingers out of his mouth." Course I knew that was going to kick up a storm because they were going to holler like hell about Potter, too. So I went out to Hank when the inning started. I said, "Hank, Sewell's complaining about you putting your fingers in your mouth. Let's not do it any more." He said, "O.K., my God, I didn't even know I was doing it." ... Art Fletcher was coaching third base for the Yankees and he came by me and he said, "What's Sewell squealing about?" I said, "About Borowy putting his fingers in his mouth." And Fletcher said, "Holy cow! Well, make Potter keep his out of his mouth, too." I said, "All right."

L-R: Cal Hubbard, Hank Borowy, Luke Sewell, Nelson Potter So the inning was over, and Potter went out to the mound. I said, "Nellie, they're complaining about you putting your fingers in your mouth. Sewell complained about Borowy, so we're not going to have any more of that today. Let's don't do it."

He did it again, so I went out to him again, and here comes Sewell running out there. I said, "Now, Luke, I've already told him twice. You're the one that started it, complaining about Borowy ... Potter does it all the time. I've already told him twice. You tell him now that if he does it any more, we're going to run him the hell out." ... So Luke talked to him. I don't know what in the hell he told him, but when we got ready to play Potter just did this [an obvious and exaggerated licking motion]. He just did it on purpose, see. I said, "Come on, you're through." I never did say he was throwing spitters. I just said he was violating the pitching rules. I had to put Sewell out, too. I knew he was going to raise hell. But he started it all, and he was a louse anyway, that Sewell; he was always bitching about something. When I threw Potter out the Yankees had two men on base, and the pitcher they put in got them out without scoring. Dizzy Dean was the broadcaster. So Diz said, "Looks like 'ol Hub changed pitchers just at the right time." I made out a report to the league, and they suspended Nellie for ten days. He had a wife and I think he wanted a vacation anyway. They said his wife gave birth to a child nine months later. I gave him the chance to be home. Potter: So we kept moistening our fingers. For some reason, Luke Sewell hollered at Hubbard about Borowy going to his mouth. He should never have done it ... So Cal kept telling me I couldn't go to my mouth. Well, I started to blow on my hand. I'd make a fist and blow on it. He said, "You can't do that." I said, "Cal, I'm blowing on my hand." He said, "I know what you're doing. You're wetting your fingers." Which I was, but he couldn't prove it. So he kept warning me to stop it, and I knew that I either had to get a little moisture some way or I was going to have trouble. So I kept doing it and he just run me out of the ball game. Did I ever throw a spitter? No, no. And Cal Hubbard never accused me of throwing a spitball. I was very surprised when they suspended me. I said to Sewell, "Heck, I might as well go home a few days." And I did; came home, went fishing a couple days. I kind of stretched it out a little bit, and then I got a wire from him. "You better get back here." It cost me about two starts. Did my wife have a child nine months later? Yeah, this is true. [Laughs] They used to kid me about it, but the rest of that story is not true. We did not name the baby Cal Hubbard Potter.

"A Second Look at Hall of Famer Happy Chandler," Marty Appel, Memories and Dreams, The Official Magazine of the Hall of Fame, Fall 2012

Succeeding Kennesaw Mountain Landis as commissioner of baseball was not unlike following J. Edgar Hoover as head of the FBI or Franklin D. Roosevelt as president of the United States. After such a long time in office ? 24 years in Landis' case ? the job was so associated with one figure that succession would be a great challenge. Albert B. "Happy" Chandler met that challenge. A skilled diplomat from his years in politics as governor of Kentucky and then as a U.S. Senator, he came to the position at a time when post-war America was beginning to face serious questions about what it stood for as a nation. One was certainly whether the National Pastime could continue in its segregated ways. African-American soldiers had served their country in World War II; could they not play anything other than Negro Leagues baseball? It was Branch Rickey, of course, who took the lead, signing Jackie Robinson to a contract in 1946 to play at Triple-A Montreal, and then to a major league contract in 1947 to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers. However, Rickey's intentions would have been thwarted if the contract was not approved by Chandler, who faced clear opposition from other owners. A reported 15-1 vote against integration had been taken at an owners meeting. "I don't want to be too hard on the old man (Landis)," wrote Chandler more than 40 years later in his autobiography, "because he wanted to keep his job ? He was doing what the owners wanted him to do."   L: Jackie Robinson shakes hands with Happy Chandler as Don Newcombe looks on; R: Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis So Chandler, despite his upbringing in the segregated south, approved the contract. He may not have been the lead player in this drama, but it didn't play out without him. It was a courageous act.

It was Chandler's style to be bold. When unpopular in New York in the aftermath of suspending Brooklyn's Leo Durocher over gambling associations, he was introduced to great booing at Yankee Stadium on Babe Ruth Day in 1948. His first words at the microphone were, "This is Albert B. Chandler." That was the man's style. Chandler made a deal for radio rights to the World Series in 1947, and for television rights in 1949, using the proceeds to establish the first pension fund for players. The money could have gone elsewhere, but Chandler saw that the time had come for pension consideration, and there was the new revenue stream to fund it. However, his decision to impose a five-year ban on players who jumped to the Mexican League may have overreached (ML baseball settled a lawsuit brought by Danny Gardella), and by 1951, sufficient support just wasn't there to extend his contract. Yankees co-owner Del Webb, angered over Chandler's inquiries over his ties to new construction projects in Las Vegas, led the opposition to extending his contract.

The Long Season, Jim Brosnan (1960)

March 9, 1959 - Cardinals' spring training at St. Petersburg FL. Manager Solly Hemus and coach Johnny Keane are going over the signs for the season.

Hemus called a meeting for the last workout before the start of the exhibition season. "We're going to use the same signs in these games as we will all year. So let's pay attention." He turned to Johnny Keane. "John?" Keane jumped onto a bat trunk waving his ever-present fungo stick for quiet. [P Ernie] Broglio murmured to me, "I think he sleeps with that goddamn bat." "These are the signs we're gonna give from 3B. Solly will be on the bench." Keane waved his bat, relegating Hemus forever to the dugout. "You pitchers get together with the catchers later and work out your own signs. These are for the hitters, and we don't want anybody missing signs, 'cause it just messes up everybody, including the guy who messes it up. Now, then, we're gonna have an Indicator, signs for bunting, taking, and hit-andrun. We're gonna have a take-off sign, and a sign for the squeeze play.

L-R: Solly Hemus, Johnny Keane, Jim Brosnan "The most important sign is the Indicator. When I rub my hand over the Cardinal on my shirt, that means a sign is on. You see me rub the bird and you watch my right hand - right hand only. Forget I got a left hand. With my right hand I'm' gonna touch some part of my uniform or body. One touch ... it might be my cap, or neck, or pants, or arm sleeve ... one touch, and you're taking. Two touches and you're bunting, three touches, hit-and-run ... on that pitch, 'cause the runner is going. Those are the three signs you gotta look for when you go up to hit.

"Now, when you're at the plate, look down at me on every pitch. Maybe I don't wanna give you a sign, but I may be pulling at my pants leg, or rubbing my ear, or tugging at my cap, anyway. They will be looking at me, too, trying to steal the signs, so I'll be trying to confuse them by doing the same things when I'm not giving sign as I do when I am. Get me? Only when you see me hit that bird do you know something's on. And when I give you the Indicator, count the number of touches that follows. Maybe I'll give you more than three signs! Maybe I'll give you four or five! I'm just doing that as a decoy, in case they start to pick something up, or we suspect they might. It only means something if I use one, two, or three touches after the Indicator." Keane had the earnest manner of a second lieutenant outlining the intricacies of an espionage deal. All major league clubs use Indicators, decoys, and signs for everything but nose-blowing. The passion for disguising these signs defies reason, although it does give the players on the bench something to do. (The manager will say, "Try to get their signs, boys.") Yet, 90 per cent of the time, the situation determines the strategy, and an experienced player knows who will bunt or when the batter is taking. Even more predictable are the steal and hit-and-run, since there are only a few men on each club that can do either one. What's more incongruous, although mathematical progression makes it improbable, I've seen the same sign used by two different clubs in the same game! "The steal sign," Keane went on, "will be given to the runner only after the batter gets the Take. We don't want you hitting when that runner is trying to steal. If we did we'd give the hit-and-run. The steal sign is either hand gripping the opposite elbow. It's a figure 4, and that's for stealing." He grinned. Nobody seemed to get it. "Let's not be missing the steal sign. You don't have to go on that particular pitch, if you don't get a good jump on the pitch. If you slip in starting, or don't think you can make it, stay on first. The only time you have to go is the hit-and-run, 'cause that hitter is swinging at the ball no matter where it is. If you don't go, you penalize the batter for no good reason. We're gonna run a lot this year 'cause we got a running club Ä€¦ that right, Solly?" Hemus nodded. "Whatever John says you can consider it came from me." "Now there's the squeeze. We have just one squeeze play. Suicide! You gotta bunt the ball! So you gotta know the play's on, and we gotta know you know it. So with a man on 3B I run across the bird, and touch my pants leg. One touch after the Indicator! You're bunting. You answer me, telling me you got the sign, by showing me the palm of your hand. Don't wave your hand at me. Pick up some dirt, look the other way, and rub the back of your hand across your back pocket. Then I see your palm and I know you got the squeeze. "Now, I yell to the runner on third, 'Make the ball go through!' and that's the sign to him that he's going in on the next pitch. Got that, you runners? If the batter answers the sign by showing you the palm of his hand, you still gotta wait for me to say, 'Make the ball go through!'" Keane cupped his hands at his mouth as he described what he would do during a squeeze play. His fungo bat slipped to the floor, its clatter echoing in the tense silence. The squeeze play commands breathless attention from ballplayers. Actually, major league clubs don't us it but twenty times a year, and it works only half the time, but the great importance of the squeeze is vividly impressed on the mind because of the depth of managerial despair at its failure. "That'll cost you fifty bucks, Brosnan! For Christ's sake, all you gotta do is bunt the ball!" Coach Ray Kaat whispered to Julio Gotay, the nineteen-year-old Puerto Rican phenom who was to open the exhibition season at SS. Julio's command of English was giving him a stomach-ache - his vocabulary was not equal to ordering a decent meal - and Katt was translating Keane's instructions. "Do you understand, Julio?" asked Keane.

Gotay shook his head. "Well," Keane frowned, "we'll go over them again tomorrow." Joe Morgan: A Life in Baseball, Joe Morgan and David Falkner (1993)

Joe is in his first ML seasons with the Houston Astros in the 1960s. Because I was one of many young players, I made friends on the Astros in a way I never did elsewhere. One of the first close friends I had on the team was Rusty Staub, still a friend today. Rusty was a southern white, I was a black from Northern California. Our habits, our upbringing, our ways of looking at the world were totally different.

I lived in the black section of Houston, Rusty lived in a white suburb. We used to go to dinner all the time, we used to go to each other's houses regularly on Friday nights when the team was in town. Rusty would come to my house, bringing other friends of his along, and I'd go to his house bringing friends of mine. We simply enjoyed each other a lot. Each of us had in his makeup something that enabled the other to connect and feel comfortable across barriers. ...    L-R: Joe Morgan, Rusty Staub, Aaron Painter I used to play golf with Rusty a lot. He belonged to a segregated country club, but I was so frequently there as his guest that I wound up leaving my clubs there along with his. One day, of course, Rusty was told that he could no longer bring me there. Rusty did not quit the club, though I am sure he did what he could to get an allowance for me. I never blamed Rusty for continuing to play there because I knew he had a good heart.

The day he wound up telling me we could no longer play at the club together he literally spent the whole day working himself up to say what he had to. When he finally got around to it, I could see how bad he felt. "Hey man, forget about it," I said. So I was more than surprised when, one day, I discovered that Rusty was involved in an entirely different kind of controversy. I got to the park early and I noticed that there was a tense atmosphere in the clubhouse. I asked someone if anything was wrong and I was told all hell had broken loose. When I asked what had happened, there was just a shrug. ... so there the matter lay until Rusty walked over to my locker. "I got to talk to you," he said. "Sure, what's up?" We went off to one side, away from the rest of the players. "You know, I really made a terrible mistake today and I don't know what to do about it." I could see that he was upset and I was genuinely concerned for him. "What do you mean?" I said. "What's happened?" "Well," he said, "you know, I'm from New Orleans, I grew up there ... If a black guy was a good guy he was a good nigger, you know?" I could feel myself tighten. "Yeah?" "You know I was having this talk with Aaron Pointer," he said, "and I happened to say to him, 'You know, I like you, you're a good nigger.' Well, Aaron hit me and we started fighting right there. The worst of it is that everybody thinks I'm prejudiced and I'm not." I didn't know what Rusty wanted from me. If he had said that to me, I would have hit him, too. I continued to believe he wasn't prejudiced, but there was no way I could help him out. "You just don't say things like that, man," I said. Somewhere between then and game time Rusty figured out that he was the only person who could help himself in that situation. He called all of the black players on the team together. There were no other white players there to back him up or lend moral support. "I'd like to say something to all of you," he explained, slowly and quietly. He told us all what he had told me and then he said, "I've apologized to Aaron and I hope he accepts that. But I also want to apologize to each and every one of you. I know that what I did was wrong, but I hope you'll accept my apology and let who I am and the way I behave speak louder than my words." I admired Rusty for that apology. It took courage and decency. Rusty for his part let his behavior speak for him though I think it was impossible to repair the relations within the team that he had damaged. Aaron had one more year with the club and was sent to the minors; Rusty, at the end of 1968, was traded to the Expos. "Turn Back the Clock," John McMurray, Baseball Digest July/August 2013

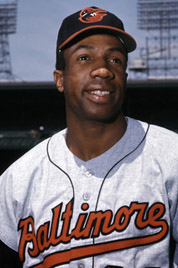

During his first major league spring training with the Baltimore Orioles, Don Baylor demonstrated a confidence that foreshadowed his success as a major league player. A confidence that was apparent to both teammates and sportswriters. "I was asked how I was going to break into an outfield of Don Buford, Paul Blair, Frank Robinson and Merv Rettenmund," said Baylor. "And I said that once I get into a groove, it really didn't matter who was out there. Frank was always in charge of the team's Kangaroo Court. So he brought the newspaper in the next day and read it in front of all the guys. The nickname has stood to this day as 'The Groove.'" The Groove made his major league debut in 1970, beginning a career that spanned 19 seasons. The right-handed hitter broke in as a left fielder, a power threat who demonstrated exceptional skill on the basepaths, stealing 20 or more bases in each of the first eight full seasons. "I loved to run the bases," said Baylor. "Chuck Tanner once told me that I was the second-best baserunner he ever had. The first was Dick Allen, another big guy who could run the bases. ?"    L-R: Don Baylor, Frank Robinson, Earl Weaver Those were talented Baltimore clubs, featuring four future Hall of Famers: Robinson, Jim Palmer, Brooks Robinson and the manager, Earl Weaver. For a 22-year-old rookie in 1972, the excitable skipper was an imposing figure. "There was only one Weaver," said Baylor. "Earl was great. He was one of the greatest managers I played for. But you feared him as a young player. Once you stepped on the field, you had better know what you were doing because if you didn't, he was going to meet you on the top step of the dugout with his hands on his hips. "Weaver always looked to have the nine players he had out on the field be the best nine he could go with that day. One day, I was hitting off of Kenny Brett when Brett was a starter for Milwaukee. I hit two homers, line drives out of the ballpark. Then we go to Fenway Park, where we're facing Sonny Siebert. Weaver says to me: 'You know those balls you hit out yesterday? They'd just be off the wall for singles here.' I said: 'Earl, I'm in the groove,' and he says, 'You're not playing.' "So I go to the outfield. I'm not taking batting practice, and I'm ticked off. Balls are going through my legs, and I'm just standing out there. You know who the first pinch-hitter he used was? Me. So I go up and hit a three-run homer into the net to tie the game. And there Weaver is on the top step, waiting to shake my hand. I just walked to the end of the dugout. So the next day he starts me against Gary Peters, a left-hander. I hit another home run. So in three different games, I hit four home runs. So he let me play for awhile. That's what you had to do, you had to prove it to him." Tales from the Red Sox Dugout, Jim Prime and Bill Nowlin (2001)

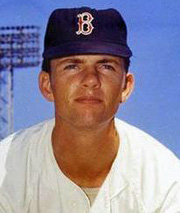

Superstition has always been a great part of baseball. When a team is going well, no one wants to be responsible for breaking the spell. In 1938, the Red Sox were on just such a winning streak, and players went to extreme measures to keep it going. During the eight-game run, the team was served lamb chops every day. Joe Cronin chewed the same gum throughout the streak, and other players tried to maintain their regular eating routines. Perhaps it was "Broadway" Charlie Wagner who made the biggest sacrifice for the team. "I was on prune juice for eight straight days," he claimed. "I'm glad we lost."

In 1986, reliever Bob "Steamer" Stanley was going through a rough time. Cursed with a sinkerball that no longer sunk, he was booed mercilessly by the Red Sox fans but still managed to keep his sense of humor. He told teammates that his actual name was Lou Stanley and that actually fans were chanting "Lou, Lou," when he walked to the mound.    L-R: Bob Stanley, George Scott, Bill Lee Red Sox first baseman George "Boomer" Scott introduced a new name into the already-rich baseball lexicon. He called home runs "taters." It quickly caught on and was adopted by the likes of Reggie Jackson and other notables.

Scott used to wear a strange necklace strung with irregular shaped white objects. When a curious teammate asked what the objects were, the menacing Boomer replied, "The teeth of American League pitchers." Bill Lee on George Scott: "I remember George Scott was in taking a shower, and Eddie Kasko was in taking a shower at the same time. George was lathering himself up with Head & Shoulders shampoo, and he had a big froth of it on his hair. Kasko, who was completely bald, looked over at George and said, Boy, I used to use that product quite a bit too!' George wasn't long rinsing his hair out." When Scott was traded to the Milwaukee Brewers, he almost won the Triple Crown. When he was traded back to Boston in 1977, however, he had lost much of his bat speed. Throwing batting practice for the Red Sox, coach Harvey Haddix threw out a challenge. "Boomer," he said, "I can throw nine fastballs in a row by you a€“ up and in." Scott smirked: "Yeah, sure." Haddix, who was approaching sixty at the time, threw seven in a row past him before Scott finally fouled one off. Boomer said triumphantly, "See, I told you you couldn't do it!" |