|

The Summer of Beer and Whiskey: How Brewers, Barkeeps, Rowdies, Immigrants, and a Wild Pennant Fight Made Baseball America's Game, Edward Achorn (2013) It is late May, 1883, the second season of the American Baseball Association.

Origin of the Term "Southpaw" "The term 'Southpaw' dates back to the 1850s," Paul Dickson, Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the Hall of Fame, Opening Day 2015

The dominant slang term for a baseball player who throws or pitches with the left hand has long been southpaw. It has been in use in baseball since at least 1858 when it made its debut in print in the New York Atlas of Sept. 12, 1858, referring to a lefthanded batsman. "Hallock, a south paw, let fly a good ball into the right field." Although the term existed before its use in baseball as a description for a left-hander (including boxers), it soon belonged to the National Pastime because it fit with the geography of the typical 19th century ballpark - laid out with home plate to the west, which meant that a left-handed pitcher faced the west and threw with his "southern" limb. This westward orientation was intended to keep the glare of the afternoon sun ... out of the batters' eyes. It also kept the sun out of the eyes of the customers in the more expensive seats behind the plate. Conversely, it allowed the strong afternoon sun to beat down on the cheap seats, which were known as the "bleaching boards" and then the "bleachers." The term "southpaw" was given its legs as a baseball term in Chicago by either political humorist Finley Peter Dunne of the Chicago News or Charles Seymour of the Chicago Herald, who both used the term extensively. According to Dunne's biographer, Elmer Ellis ("Mr. Dooley's America," 1942), Dunne invented the term for a left-handed pitcher in "about 1887" because the "Chicago ball park faced east and west, with home plate to the west, so that a left-handed pitcher threw from the south side." H.L. Mencken ("The American Language," Suppl. II, 1948) reported that Richad J. Finnigan, publisher of the Chicago Times, attributed the term to Seymour. As Finnigan put it in a 1945 letter to Mencken: "The pitchers in the old baseball park on the Chicago West Side faced the west and those who pitched left-handed did so with their southpaws." The term got a literary boost in 1953 as the title of the first Henry Wiggen baseball novel by Mark Harris. "The Southpaw" was followed by the classic "Bang the Drum Slowly." Slang synonyms for southpaw include portpaw and portsider (alluding to the left or port side of a ship), as well as forkhanders, hook armers, wrong armer and the Spanish zurdo. The term northpaw for a right-handed pitcher has been used on rare occasion, but has never gained popularity.

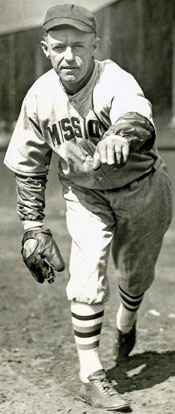

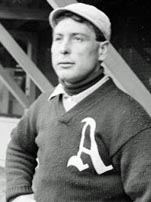

Rube's Crackers Have to Go

Rube Waddell: The Zany, Brilliant Life of a Strikeout Artist, Alan H. Levy (2001)

Before the 1903 season began, [Philadelphia A's manager Connie] Mack sat Rube down to go over some contractual matters. Rube signed the standard player contract but with an added provision especially for Rube that Mack insisted he accept. The provision stemmed from discussions with [catcher] Ossee Schrecongost a few days earlier. Schreck easily came to terms with Mack, but he made one little request – that Rube be forbidden from eating "animal crackers" in bed. In those days, roommates shared a bed when the team traveled. It was standard practice throughout baseball. Schreck was the only man who could live with Rube. But the one thing that got under his skin, literally, was Rube's munching animal crackers in bed. "The big bum has got to where he eats these little animal crackers every night. I didn't mind the flat crackers so much," Schreck complained. "But for a whole week last year I woke up with elephants' tusks and cowhorns stickin' 'tween my ribs."

The mere thought of having to assign another player to room with Waddell made Mack instantly agree to Schreck's odd little codicil. Rube made no fuss about it. He liked Schreck and didn't want to rile him. Not another word was said about the animal crackers, and Rube never ate animal crackers in bed again. A few days after the cracker deal, Rube did exact a little revenge, not on Schreck but on Mack. The team was still in Florida, and late one night Rube knocked on Mack's door. Mack answered, "I am in bed, but come in if you'd like." Rube did, and proceeded to speak some inanity to Mack as he ate a sandwich. While eating, Rube made sure he dropped an appropriate amount of crumbs and other sandwich contents in Mack's bed. The sandwich didn't contain animal crackers, just raw onion and limburger cheese.

L-R: Connie Mack, Rube Waddell, Ossee Schrecongost Robert P. Lockwood, Franciscan Newsletter, May 2015

Exposition Park, home of the Pittsburgh Pirates 1890-1909 The next day at the Allegheny Police Station, Father Walsh showed up with a fellow priest. The priest spotted an old buddy who was a retired detective. He asked the former detective how he could get his friend out of this mess. His answer: have him apoloize to Dreyfuss. So Father Walsh, finally admitting his identity, stepped up to Dreyfuss and apoligized profusely for his actions the day before. "I accept your apology," Dreyfuss replied. "I bear no enmity and have no desire to prosecute you," Dreyfuss said, while still sporting a shiner. The charges were dropped. But the story got added cachet with the report that Pittsburgh diocesan priests were banned from baseball games. As far away as San Francisco, newspapers reported that "the Right Rev. Mr. Kittel, acting in the absence of Bishop Canovin, who sailed for Rome, has ordered all priests to stay away from ballgames. In the past from 60 to 70 priests have attended every contest." I couldn't find any evidence that priests were actually banned from ballgames for any serious length of time. Perhaps Father Kitel issued such an edict to the priests in Bishop Canevin's name while he was away. But there was no such statute in diocesan files. And what of Father Walsh? He was pulled from his church the day of the altercation. He was assigned after a two-month wait to a parish far away from the ballpark. His career as a deadhead was over. But his priestly vocation continued. Father Walsh would later serve as pastor in four parishes down through the years. He died a priest in good standing on July 21, 1923.

It's Not Smart to Irritate The Lip

The Lords of Baseball, Harold Parrott (1976)

It is 1945. Branch Rickey has gone to the Dodgers from the Cardinals. Leo Durocher is the Brooklyn manager, and Harold Parrott is the traveling secretary. The fans in St. Louis felt that Branch Rickey had deserted them to build in Brooklyn a juggernaut that would one day crush their Cardinals ... Rickey carried an open grudge against Cardinal owner Sam Breadon. The Mahatma had made millions for Breadon, auctioning off to other sucker owners more than $2.8 million in castoffs while keeping the players needed to win five pennants and four world championships. Rickey felt his reward had been to have Breadon betray him when he needed support to fight Judge Landis's vendetta against the far-flung "chain-gang" farm system. ...

On the eventful September night in 1945 ... Durocher turned the entire National League pennant race around, because he felt his downtrodden Dodger team, hopelessly out of the race, had been humiliated and belittled by Breadon. For Breadon, his double-cross of Durocher just to pick up a few more bucks in an illegal doubleheader was one of the dumbest blunders any one in baseball's House of Lords [the owners] ever pulled off. ... The moment Leo got wind of Sam Breadon's dirty trick, he began acting like a crazy man; and he never stopped for the next thirty-six hours.

L-R: Sam Breadon, Branch Rickey, Leo Durocher Until that night, the Cardinals had been coming fast; they had streaked from far back in the race to a point where they would be only a game and a half back of the league-leading Cubs if they could trample the Dodgers twice this night. That did not figure to be too tough,

for Durocher and his team had been sauntering through September with a "who cares?" smirk. The Lip had originally intended to throw two "give-up" pitchers, Clyde King and Les Webber, against St. Louis in the last two games of this series. The Cards had chewed Ralph Branca to bits in the first game.

Leo was saving his two best, Vic Lombardi and Hal Gregg, to pitch against the Cubs in the next series in Chicago. The Cubs were staggering and had lost again that afternoon. That was Durocher's way: Save your best to knock off the guy on top. But Breadon changed all that. It had rained on our second night in St. Louis. And now, instead of playing the postponed game on the afternoon of our final day there, as the rules required, the owner of the Cardinals was forcing us to play a twilight doubleheader. The old skinflint knew, because I had told him, that this night doubleheader - before the next day's afternoon game in Chicago - would cost us our Pullman sleepers on the regular night train and would force us into an all-night situp ride in a chair car at the end of a long freight. Leo knew it, too, and he had blown up when I told him what Breadon was planning. All night long the two of us kept calling Ford Frick, the National League president ... But Frick wasn't answering his phone. He wanted no part of a hot potato like this, because Breadon was a powerful owner in league councils, and Ford needed his vote next time his contract came up. ... It became clear on the sunny afternoon when we should have been playing that Breadon was gong to get away with his night doubleheader; and Durocher got madder and madder instead of shrugging it off. He got hold of Gregg and Lombardi ... and told them he was going to use them that night to "kill" Breadon and the Cardinals. He started to psych up his whole team in the lobby of the Chase Hotel before we left for the ballpark. This wasn't easy. It was a joke of a Dodger team, a crazy quilt of has- beens ... and never-was ballplayers ... Once at the park, the Lip strutted like a Napoleon in a baseball suit in front of his troops as they warmed up. "Look at that plush-lined bum up there in his private box," he stormed, pointing to where Breadon sat. ... A steady drizzle was falling now, to make things worse, if possible. "Fuckin' Ol' Moneybags is makin' you risk your arms and legs ... down here in this mud!" ... Nothing else mattered to Leo right now except knocking Breadon out of the pennant race. He had spent half an hour getting Lombardi keyed up to pitch this first game. ... Ken Burkhart was a sixteen-game winner, but Brooklyn hitters he could usually handle stomped all over him this night. Playing as if they were in the World Series, Durocher's men grabbed the first game, 7-3. It was raining harder now, but that didn't cool Leo off. The Cardinals were stunned when they saw ... Gregg ... warm up for the second game; they knew the Lip had been saving him for the Cubs the next afternoon. In the dugout we could hear the manager screaming, "Breadon took away your Pullman sleepers tonight. He's treating us all like animals, making us ride in a cattle car!" The Dodgers climbed all over Charley Barrett right from the first pitch. ... [He] never got out of the first inning. Gregg coasted to win it. Breadon, instead of being on the Cubs' heels, was now three and a half back and fit to be tied. The few bucks he had tried to make at the Dodgers' expense were about to cost him a bundle. Although he didn't know it right then, the pennant race was over. It was long past a wet, cold midnight when the ... Dodgers began to straggle onto the train platform. We usually went first class, with two sleeping cars ... But wartime travel restrictions, plus Breadon's dirty trick, had changed all that. ... Durocher stopped to chat with the engineer, who was already up in his cab, anxious to turn it loose. They were already more than an hour late ... Had Charley Tegtmeyer known, he'd have stretched out this little chat, instead of rushing it. It was to be his last night on earth. ... "A dirty trick that was," Charley began. He lived in Chicago and was a double-dyed Cub fan ... "How could they force you to play two on a night like this when you gotta be on the field at noon today in Chicago?" " The thin glow that was the edge of dawn was beginning to show up ahead of Old No. 70, and she seemed to be leaping like a hungry horse nearing the barn [forty miles outside Chicago]. Even Durocher ... was catching forty winks [after an all-night poker game] ... When it happened, most of us thought it was the end of the world. Every window on both sides of the car lit up with that wild, dancing brightness you see in blast furnaces. Outside, an inferno was raging. The whole train, running full throttle a few moments before, was now bumping and swaying in a tortured way as the air brakes blew. ... Up front half a tanker-trailer rig was astride Charley Tegtmeyer's locomotive, and the 2,000 gallons of gasoline it had spilled on the cab had cooked Charley to death before spraying aft to ignite the rest of the train. ... As Durocher herded his charges like dazed children out the back door and down into the sharp morning air on the roadbed, they could look back at the death trap they'd all been carried through by sheer momentum ... All Durocher could do was to keep repeating, "Breadon ... that miserable bastard ... Breadon ... he should be here to see what he caused ..." In three hours the fireman was dead, and just about that time the Dodgers, not much better off, staggered out onto Wrigley Field. Les Webber, dead on his feet, did the best he could ... but the Cubs ate him up. Back in St. Louis, the Cardinals were also very, very dead. Run over, you might say, by Breadon's night freight. Dynasty: The New York Yankees 1949-1964, Peter Golenbock (1975)

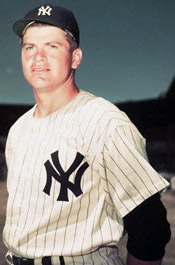

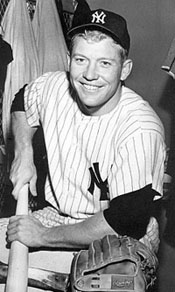

P Bob Turley helped Mickey Mantle immensely from the dugout.

"It got so that when I wasn't pitching and wasn't doing too well and wanted to go to the bullpen 'cause I wanted to get into the game, the hitters would go Stengel and say, 'Get him back here on the bench.' They wouldn't let me go to the bullpen. In fact there was one time when I had an injury, and they put me on the disabled list, and I had to sit in the stands, and they had a special seat for me so I could be close to home plate to call the signs."

Death of a Dynasty

October 1964, David Halberstam (1994)

The Yankees are embroiled in a tight pennant race in 1964. The old Yankee magic wasn't working. The other American League teams no longer rolled over and played dead for them. Indeed, the older Yankee players noticed something new: one of the key Yankee weapons - intimidation - no longer worked. Other teams, for instance, the up-and-coming Baltimore Orioles (managed by ex-Yankee Hank Bauer), not only had talented young players such as Boog Powell and Brooks Robinson in their regular lineups, but their pitching staffs might well have been better than that of the Yankees. ... The ownership of other teams was getting better and more professional, their systems were better, with better scouting, while meanwhile the Yankee system was in decline. The old Yankee recruiting pitch - that if you signed with the Yankees you got less money in the short run and more in the long run as well as the chance to play with the best - had less and less appeal. Young men were signing with the team that offered the most money, and after the Yankee scouts made their pitch, rival scouts whispered that if you signed with the Yankees, you remained buried in their farm system.

George Weiss, the unpleasant but skillful creator of the great dynasty, had been aware by the late fifties that Dan Topping, the more involved of the Yankee owners, wanted to get rid of him, so Weiss had begun to cut back on his investment in the farm system and in signing young players. Whether Weiss had cut back to improve his own numbers, for his bonus was based, in part, on the profits each year, or to show two increasingly disenchanted owners who took the team's success for granted that he could still run a professional baseball team, no one was sure, but there was no doubt they had cut back. Moreover, they were paying much more heavily for Weiss's racism than anyone had realized at the time. That racism was an unfortunate reflection of both snobbery and ignorance: Weiss did not think that his white customers, the upper-middle-class gentry from the suburbs, wanted to sit with black fans, and he did not think his white players wanted to play with blacks, and worst of all, he did not in his heart think that black players were as good as white ones. He did not think that they had as much courage or that they played as hard. That ... was his single biggest mistake. For in the past a key to the Yankee success was that in addition to signing such superstars as DiMaggio and Mantle, they had always been able to sign a prototype player who was at the core of winning baseball - a very tough kid, wildly aggressive, who played hard, and who often signed with the Yankees for less money than he had been offered elsewhere because the Yankees ... always won and these kids wanted to win. They were hungry, and they were driven for success; for them, being in the big leagues was not enough; they wanted to excel once they were there. These were players, Henrich, Bauer, or Kubek, who maximized their ability, who played above their level in pennant races and World Series games, and who helped give the Yankees their special advantage of playing well in tough games. ... Here, more than anywhere else, ... Weiss's racism had egregiously blinded him, for he did not see what was in front of him every day: that young black players coming into the big leagues exemplified the mental and spiritual toughness now that the Yankees once demanded. Their lives had been strewn with far more obstacles than the white players'; since owners monitored how many black players they carried, there were very few black bench warmers or backup players then. Either you were a starter or you did not make it. George Weiss did not understand the rage to succeed that drove so many of these young men, the passion to make up for so many years of racism and segregation and to avenge wrongs inflicted on those who had gone before them and who had been denied the chance. ... The Yankees were not a team that would have signed a Bob Gibson, for Gibson would have been too threatening to many of the people in management. It was no surprise that when the Yankees had finally brought up a black player, it was Ellie Howard, a talented, immensely hard-working player without the speed that marked the new generation of black stars ... If Vic Power, the great black Puerto Rican player, who had shown a quick bat and a great defensive ability in the Yankee farm system, had been somewhat different in his temperament, he might have been the first black Yankee, but Power did not fit the Yankee mold. ...

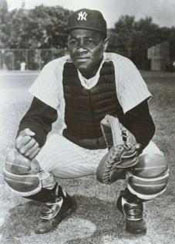

L: Yankees principal owner Dan Topping and GM George Weiss; M: Elston Howard Ellie Howard came up in 1955, two years after Power was traded. He was the perfect player to break the Yankee color line - he had a sweet disposition, and he had the capacity to bury deep within himself the racial wounds inflicted by society. ... He was a man of the older generation, and his strength manifested itself not in rage at the injustices around him, as Bob Gibson's did, but in his ability not to show his rage. ...

Sparky Who? They Call Me Sparky, Sparky Anderson with Dan Ewald (1998)

Sparky made it to the major leagues as a coach under manager Preston Gomez for the San Diego Padres in 1969. When lifelong mentor and unofficial spiritual guru Lefty Phillips was named California manager for the 1970 season, Sparky made the switch to the Angels.

He never got the chance to put that Angel halo on his head. In one of those magical moments of fate, Sparky's career took a U-turn that not only changed his life, but also baseball's record books. ... It happened suddenly and unexpectedly on a typical autumn California day in October, 1969. Sparky and Phillips had returned from lunch to the office of California Angels General Manager Dick Walsh. The three were discussing the possibility of trading for outfielder Alex Johnson when Walsh received a phone call. After hanging up the phone, he looked directly at Sparky.

The Reds arranged for Sparky to fly to Cincinnati that evening for a press conference the next morning. The day after the press conference, a headline in The Cincinnati Post read "SPARKY WHO?"

Certainly the headline was appropriate. The new manager of the promising Cincinnati Reds was a thirty-five-year-old lifelong minor leaguer. Nobody knew who George Anderson was. And this Sparky sounded more like a cartoon. Even Sparky had no idea when he was being considered for the job. The Reds had not yet exploded into prominence. But they were next up on the launching pad. They were loaded with young talent and just a step away from erupting into nationwide notoriety. "All I could figure is that when I played in Philadelphia, we won 60 games," Sparky said. "When I coached at San Diego, the Padres won 50 games. Bob must have figured I had only 110 wins on my side in the major leagues so I had to have a whole lot more hidden somewhere inside of me." ... So in spite of the shock of the baseball establishment, Sparky Anderson was off on a career at Cincinnati that didn't end until he set the franchise record of 863 victories. They went along with two World Championships and four National Legue pennants in a span of nine years.

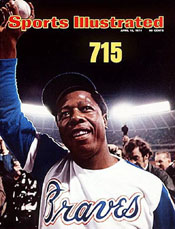

Sports Illustrated, 7/7/2014

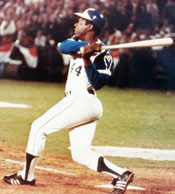

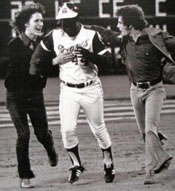

From an article on Hank Aaron's HR against the Dodgers on

April 8, 1974 that broke Babe Ruth's record for most career HRs.

Memories of Howard

From You Can't Make This Up: Miracles, Memories, and the Perfect Marriage of Sports and Television, Al Michaels as excerpted in Sports Illustrated 11/3/14

Often when Cosell and I worked baseball together, we were joined in the booth by Uecker. He was supposed to play the role Don Meredith did on Monday Night Football. Johnny Carson, who had Uecker on as a guest close to a hundred times, once said that Bob might be the funniest man ever. He's certainly in the conversation. To this day almost anything out of Uecker's mouth makes me belly-laugh. A lot of his great stories revolve around how inept a player he was during his career in the 1960s. ("I hit a grand slam off Ron Herbel," he said, "and when his manager, Herman Franks, came out to get him, he brought Herbel's suitcase.") And Uecker has always been quick with a rejoinder. That came in handy when he was in the booth with Cosell.

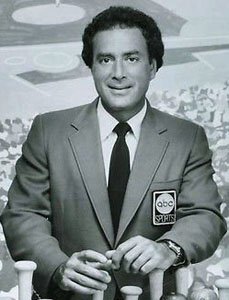

Cosell's knowledge of baseball might best be described as shallow. He thought he knew everything about the game, but he really knew very little. If he was in the booth for a Monday-night Yankees game in May, with the opposing team leading 8-1 in the third inning, he might say the Yanks should bring in Goose Gossage to put out the fire. There was little use in explaining to Cosell that, no, in the third inning, with the Yankees trailing by seven, it would border on insanity to call on their best reliever, a future Hall of Famer. To Cosell the conventional analyst was just another dumb jock. He was Howard Cosell! He knew better.   L: Al Michaels; R: Howard Cosell Once, in the early '80s, Cosell, Uecker and I were doing a game at the Astrodome. At one point in the late innings Cosell called for a bunt even though it was a situation in which no one would ever bunt. Uecker wanted to mildly chide Cosell but knew he had to be careful. "Well, Howard, I'm not really sure you want to bunt here," he said gently. He went on to explain why. Cosell responded, "Uecky, I get your point. But you don't have to be so truculent. You do know what truculent means, don't you?" Uecker didn't miss a beat: "Of course, Howard. If you had a truck and I borrowed it, it would be a truck-you-lent." Uecker could also use me as his straight man. Another time we were talking about Charlie Finley, the eccentric owner of the A's, and his proposal to manufacture all baseballs in the same yellowish orange as some tennis balls. The idea was that the brighter baseballs would be easier for fans to follow.

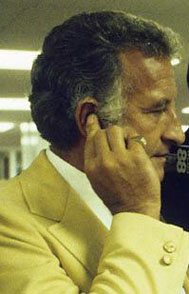

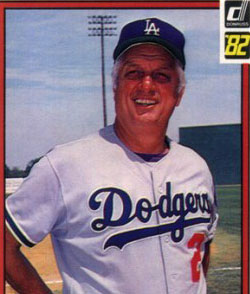

L: Bob Uecker; R: Tom Lasorda At the end of the 1982 baseball season Cosell and I were set to work the National League Championship Series. The third spot in the booth was still to be determined. Arledge was always big on bringing in someone in the news. So that Sunday night the call went out to Tommy Lasorda. Lasorda had won three pennants with the Dodgers and a World Series title the previous season. But now, with his club eliminated from the playoffs, would he be interested in a brief sojourn into broadcasting? The answer was yes.

Lasorda and I had crossed paths countless times over my years calling games for the Hawaii Islanders, the Reds, the Giants and ABC. Now we were together in St. Louis for the National League playoffs. It was the Cardinals versus the Braves. Baseball in October. Beautiful. Except that Lasorda looked petrified. As we rehearsed the opening segment, I had to keep telling him, "Tommy, it'll be O.K. You'll be fine." Cosell opened up the telecast. Then he brought me in. Then I brought Lasorda in. Cosell and I talked with him about the two teams. The Cardinals do this, the Braves do that. Here are their strengths and weaknesses. So far, so good. Then Cosell was ready to take us to a commercial. But before he did, he said, "O.K., throwing out the ceremonial first pitch are the children of the late Cardinals third baseman Kenny Boyer, who succumbed a fortnight ago, at the age of 51, to the ravages of lung cancer. Kenny Boyer fought that insidious disease tooth and nail to the very end. He went to Mexico for laetrile treatments and absorbed more radiation than anyone thought humanly possible. "So when you look at the long and storied history of the St. Louis Cardinals franchise, you can go back and you can have your Rogers Hornsby. You can have your Joseph (Ducky) Medwick and Jay (Dizzy) Dean as well. You can take Albert (Red) Schoendienst and, yes, even the Man himself, Stanley Frank Musial of Donora, Pennsylvania. Because when it comes to the embodiment of the St. Louis Cardinals franchise, look no further than the countenance of one Kenton Lloyd Boyer. He was a man's man. And we'll miss him." Cosell then lowered his voice another notch: "We'll be back after this." There was nothing Cosell loved more than delivering a eulogy He would affect a "half-mast" voice. Didn't matter who it was. Cosell wanted to show you how much he knew about the deceased and how well he could put their lives in context. We went to commercial. We had been using hand mikes, and now we put our headsets on. I started jotting something down in my scorebook. Cosell, of course, was preening after delivering his Boyer tribute. I thought I heard sniffling in my headset. Then I heard it again. I looked over at Lasorda. His eyes were moist, and I saw little rivulets running down his cheeks. Cosell saw it, too, and he said, "Tommy! What's the matter?" Lasorda's voice broke as he said, "Howard, in the minors I actually roomed for half a season with Kenny Boyer. I loved him. He was one of my dearest friends. What a man. A tremendous man. Howard, I've never heard a eulogy like that. Only you could do it. That was just beautiful." Cosell leaned back. He had the cigar going. He said, "Hey, Tommy, just understand one thing. Kenny Boyer was a prick!" It was quintessential Cosell. Show everyone how smart you are, show that you know every player's middle name - Stanley Frank Musial, Kenton Lloyd Boyer - and just make it part of the show. But it calmed Lasorda down. And we went on with the game.

Bob Gibson Stories

Stranger to the Game: The Autobiography of Bob Gibson with Lonnie Wheeler (1994)

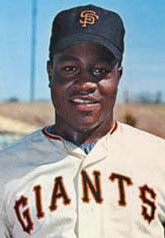

Jim Ray Hart, San Francisco Giants: It was my first day in the big leagues in 1963, and in the opener of the doubleheader I'd had a good game against the Cardinals' Bobby Shantz. Between games, Mays came over to me and said, "Now, in the second game, you're going up against Bob Gibson." I only halflistened to what he was saying, figuring it didn't make much difference. So I walked up to the plate the first time and started digging a little hole with my back foot to get a firm stance, as I usually did. No sooner did I start digging that hole than I hear Willie screaming from the dubout: "Noooooo!" Well, the first pitch came in inside. No harm done, though. So I dug in again. The next thing I knew, there was a loud crack and my left shoulder was broken. I should have listened to Willie.

Gibson on his struggles early in the 1964 season: I was extremely irritable during my tailspin, of course, and to his credit - although I didn't see it that way at the time - Gene Mauch, the Philadelphia manager, effectively took advantage of my temperament one May night in St. Louis. I was leading the Phillies 7-1 in the fourth inning when Mauch ordered his pitcher, Dennis Bennett, to knock down Javier. It seemed that the Phillies had been indiscriminately throwing at several of our players all night, and after Javier went down I was compelled to toss a couple of hard ones over Bennett's head. Mauch knew I would do this, and he also knew that I was at the boiling point. He had been agitating me all night from the bench, trying his best to get me angrier and angrier. The next time I came to bat, he called in Jack Baldschun from the bullpen. According to what I was told by Dick Allen, the Phillies slugger who later played a year with us in St. Louis, Mauch had called down to his bullpen coach, Cal McLish, and ordered McLish to warm up both Baldschun and Ed Roebuck. Then, as Baldschun walked to the mound, Mauch called McLish back and told him to have Roebuck ready because Baldschun was about to get thrown out of the game. The way I heard it - and the way it appeared to me at the time - when he met Baldschun at the mound Mauch told him he had four chances to get me. The first three came close and the fourth one nailed me in the left thigh. Without thinking, I flung my bat in Baldschun's direction and headed for the dugout looking for Mauch, who was long gone by that time. Naturaly, I was ejected, which is exactly what Mauch was counting on. We won the game anyway, 9-2, but I hadn't lasted the five innings required to pick up the victory, which would haunt me later in the season when I was closing in on twenty.

L-R: Bob Gibson, Jim Ray Hart, Gene Mauch From Joe Morgan: A Life in Baseball, Joe Morgan and David Falkner:

Gibson was a notoriously fast worker as well as a ferocious competitor. If you so much as fiddled with the bill of your cap during an at-bat you were in for it. A fellow rookie on our team [the Houston Astros] named Aaron Pointer once fouled a Gibson pitch off his foot. When Pointer stepped out, Gibson didn't make a mental note to relay word to him that in the future he better watch out. Even though the count then was 0-2, Gibson drilled him in the ribs with the next pitch. Bob Aspromonte, another player on our team, broke Gibson's rhythm in one game by briefly stepping out on him. Gibson hit him in the back with the next pitch. It sounded like a cannon shot. Aspromonte was out for almost a month. Gibson games lasted less than two hours - and the main reason was that no one was ever willing to stand in against him one second longer than was absolutely necessary. |

George Washington Bradley

George Washington Bradley

.jpg)

Barney Drefuss

Barney Drefuss Bob Turley

Bob Turley

Cliff Courtenay and Britt Gaston congratulate Aaron as he rounds the bases.

Cliff Courtenay and Britt Gaston congratulate Aaron as he rounds the bases.