|

Babe: The Legend Comes to Life, Robert Creamer (1974)

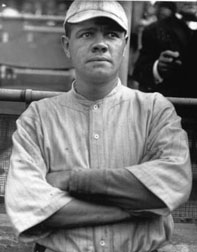

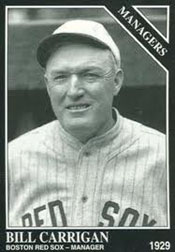

Babe Ruth is in the midst of the 1915 season, his first full season with the Boston Red Sox. Ruth was having a marvelous time. At the very beginning of the season, when the club made its way from Richmond to Philadelphia, he stopped in Baltimore for [his wife] Helen, and in Boston they set up housekeeping in an apartment hotel, living by themselves as a married couple for the first time. When he was on the road and Helen was back in Boston, he found friends. Washington was a particularly favorite town of his. There was no Sunday baseball in Washington then, and one Saturday after the game he asked [Manager Bill] Carrigan for permission to go to Baltimore to spend Sunday with his father. Carrigan said he could, as long as he was back with the team on Monday, and Ruth took off. On Monday he reported in plenty of time, and everything would have been fine, except that his father had a seat just behind the Boston bench and when he saw Babe shouted, 'You're a fine son, George. Down in this neighborhood and don't even come to see your father." Carrigan, standing there, heard this, but all he did was look at his errant ballplayer. Ruth didn't say anything. "There wasn't much for me to say," he admitted later.Ruth's off-field behavior was a problem for Carrigan. In part it was a result of Babe's natural ebullience, but it was aggravated by his new-found affluence. When Babe signed his first Red Sox contract in July 1914, his salary, which had already been tripled during his half year in Baltimore, was doubled again by [owner] Lannin to $3500, not bad for a rookie in that day. ?   Carrigan finally had to step in and bring Ruth back to earth. "He had no idea whatsoever of money," the manager said. "You've got to remember his background ? that orphan asylum and all ? and that this was his first big job. He was getting $3500 and that was all the money in the world. He didn't seem to think it would ever run out. He'd buy anything and everything. So I would draw Babe's pay and give him a little every day to spend. That generally lasted about five minutes. At the end of the season I had to give him the rest of it. I calculated it wouldn't last too long, but that was the best I could do. Carrigan had to rein in Ruth on his recreational activities too. When Babe first joined Boston, Carrigan took him aside and said, "I hear you like to step out, Babe." Ruth shrugged an embarrassed shoulder. "All right," Carrigan said, "I just want to tell you this. You play fair with me, and I'll play fair with you." Ruth promised but continued to roam. Finally, to keep a closer eye on him, Carrigan arranged for adjoining hotel rooms when they were traveling. Ruth and Heinie Wagner, a veteran infielder who functioned primarily as a coach, shared one of the rooms. Carrigan and [P Dutch] Leonard, who was something of a wanderer too, took the other. "There was no trouble, if that's what you mean," Carrigan protested years later. "He behaved himself." More or less, anyway. Certainly, he had a respect for Carrigan that he did not have for future bosses, but he was still constantly on the move, trying to see and experience everything, eating, drinking, spending all his money, exploring the demimonde that exists on the fringes of major league baseball.Tom Meany in Baseball's Greatest Players (1953):

Now Pitching: Bob Feller, Bob Feller with Bill Gilbert (1990) That senior year in high school may qualify me for the shortest one on record ? under five months. Having arrived in early October at Van Meter [IA] High, I left in February for spring training. I was headed for my first full season as a major leaguer. ? There was a lot of talk around baseball that I was a flash in the pan, a hard-throwing kid who would never again have the half-season that I had in '36. The hitters would catch up with me, some of the talk went, especially my second or third time around the league. ? And then there was always the matter of finishing my high school education. The Indians hired a New Orleans teacher to serve as a tutor so I could complete the studies necessary for me to graduate on time. When I wasn’t working on my fast ball, curve and change of pace, I was working on my English, history and math ? the only pitcher in baseball who had to do homework in the evening at the hotel.

The Indians traveled north with the New York Giants aboard their private train ? Baseball teams would come north from spring training with another team and play each other in various towns along the way to help pay for the expenses of spring training ? The Giants decided to send their ace, Carl Hubbell, against me in several games on the trip, not to prove anything about Hubbell, the great Hall of Famer, or any of their other players, but to put as many people as possible in the ballparks along the way. ?

In our first duel, I pitched three innings in New Orleans, didn’t allow a hit and struck out six batters, four of them in a row. By the end of the trip, we drew 37,000 in the Polo Grounds in New York, the largest crowd until then ever to see an exhibition game, and we went seven innings each. When I left, the Indians were leading, 2-0. My stats for the trip showed I pitched 27 innings against the Giants, struck out 37, gave up seven runs and didn’t lose a game. As good as those numbers were, what mattered even more to me was the assurance that 1936 had not been a freak year. ? All the preparations ? were behind me now as I stood on the mound back home in Cleveland, ready to face the St. Louis Browns in our first home series of the 1937 season. ? My third pitch of the game, on a 1-1 count, was a curve ball. It was raining and the mound was slippery and greasy. I slipped and lost my balance just as I was releasing the pitch. My arm popped. You could hear it all over the infield. I felt a severe pain in my throwing arm before the ball even reached the plate. My right elbow was killing me.

Now I was throwing hurt, not the brightest thing a pitcher can do, but when you're a kid trying to make it, you don’t want to miss any chance you get, and this was a big chance for me. I kept on pitching, but the result was predictable: Four runs by the Browns in the first inning, with the help of four walks. This was no way to establish myself, so I couldn’t leave with that as my performance. I decided not to tell anybody about my arm. I was going to keep on pitching, pain or no pain. I could scream my guts out after the game. Things did not get better immediately. With one out in the second inning, I walked three straight batters. Now the game is only four outs old as far as my pitching is concerned, and I've walked seven men already. I kept my fingers crossed that [Manager Steve] O'Neill wouldn't yank me ? The plot thickened when who should step up to the plate but my boyhood hero, Rogers Hornsby. As if I didn't have enough awe for him already, he had clobbered a 450-foot HR the day before off Johnny Allen, our best P. But I was able to put the pain out of my mind just long enough to strike him out and then do the same with Harlond Clift. I was out of the inning without any more runs by the Browns. I still kept my injury, if that's what it was, a secret on the bench. The only thing pitchers fear as much as arm trouble is a reputation for it, and I didn't want either one. ? After six innings, though, the pain was unbearable. I finally told Steve my depressing news. O'Neill, of course, got me out of the game immediately for my own good. There was one consolation for me: Even while throwing in pain to every batter I faced in the whole game, I gave up only four hits and got 11 of the 18 outs by strikeouts. If a teenager pitching in severe pain can do that, surely there must be a future in the sport for him. I wasn't really that worried at first, although the Indians certainly were, especially management. But when days stretched into weeks and weeks into two months, I began to worry too, and everyone else was in a state of panic. Was fate being cruel and snatching everything from me just after putting it within my grasp? Two months of X-rays, massages, secret trips to doctors, daily bulletins in the Cleveland papers, various experiments ? each a failure ? were causing everyone to worry more, including me. ?

In the middle of it all, I had to leave the team to go home to graduate from high school. ? NBC covered the ceremonies "live" coast-to-coast on its "Blue" radio network. They told me it was a first, the only high school graduation carried live on nationwide radio. I was beginning to get used to "the press," and my interviews included two on Station WHO in Des Moines with the local sportscaster, Ronald Reagan ?

After I flew back to Cleveland, we tried other cures for my ailing elbow, all with the same discouraging results. ? Cy Slapnicka had moved up the ladder from scout to GM in the fall of 1935. Having discovered me, he felt a personal involvement. He was determined he was going to find somebody, somewhere, who could solve this problem. He found him almost under his nose ? a few blocks from the ballpark. He was one A. L. Austin, a small, powerful man ? who practiced something called mechano-therapy ? bone and muscle manipulation. He was an apprentice to the world renowned "Bonesetter" Reese ? Austin ran his strong fingers up and down my right arm as I sat on his examining table. Then the specialist in this strange new field turned to Slap and said, "This boy has adhesions in his elbow. Hold on, son." Then he grabbed my right wrist with his left hand and my elbow with his right. He gave a sudden twist ? and darn near pulled my arm apart. The pain was blinding, but only for a moment. Then, magically, the pain was gone.

Austin said to me, "There, that ought to do it. Now you take a rest for 24 hours and go right out and pitch. Don't worry about it." It would have been impossible to tell who was more elated Slap or me. We just about danced our way out of that office. And the next day, when the elbow still felt great, we were ready to jump out of our skin all over again. Austin's bill to the Indians was $10.00. The acid test came a few days later ? in the first game of a Fourth of July doubleheader in Cleveland. I hadn't pitched since April ? only six innings all year ? but 30,000 fans showed up ... It was no Cinderella story. No, I didn't pitch a no-hitter. I didn't even pitch a complete game. But I did pitch four strong innings and struck out three hitters in a row at one point. Then O'Neill took me out as a precaution and ordered me to go to the clubhouse for still another examination by the team physician Dr. Castle looked my arm over thoroughly ... Then he patted me on the shoulder and said, "It's as good as the day you were born."I had weathered my first baseball storm. ? The Indians not only found the man who could cure me, but also saved my career by resisting the temptation to order me to pitch with the pain in the hope that it might work itself out. That sounds insane, but I’m sure some teams and some managers would have done just that. "Ted's Philadelphia Story," Tales from the Red Sox Dugout, Jim Prime with Bill Nowlin (2001)

September 27, 1941, was a drizzly late summer evening in Philadelphia. It had rained hard earlier in the day, canceling the ballgame, and passersby rushed heads down along the tree-lined streets, scarcely noticing the tall athletic man and the shorter, stockier man walking along in animated conversation. Few of the onlookers were aware that the taller man was on the verge of a feat so rare that it has not been repeated in any baseball season since. They walked through business areas and neighborhoods with immaculately manicured lawns. Occasionally, the shorter man would duck into a bar for a quick refresher, while the athlete went for ice cream. The taller man, Red Sox phenom Ted Williams, and his less imposing friend, clubhouse boy Johnny Orlando, were talking hitting ? specifically the next day's season-ending doubleheader between the Red Sox and the hometown Athletics. Ted reckons they walked about ten miles that night. Exactly what was said is long forgotten, but knowing Williams, he was analyzing the pitchers he would see the next day ?

Ted Williams and Johnny Orlando The last time anyone had batted .400 was 1930, more than a decade earlier, when Bill Terry batted .401 for the NL's New York Giants. Terry had been the closest thing Ted had to a boyhood idol. The last American Leaguer to reach the mark was Harry Heilmann, way back in 1923. As he walked, Ted remembered the encouraging words he had heard from Heilmann just a few weeks earlier: "Just hit the way you can hit, and you'll be all right."

Going into the twin bill, Williams was batting precisely. 39955, which for math majors everywhere, and certainly by major league baseball standards, would make him a .400 hitter. But Ted's personal standards were even higher. He did not want to leave his fate up to the discretion of a statistician in some airless league office. Earlier that same evening, Sox manager Joe Cronin had suggested that maybe Ted would like to sit out the last two meaningless games to preserve the coveted mark. Ted's reply was as blunt as it was powerful. "If I can't hit .400 all the way, I don't deserve it," he said. There was no argument.

Harry Heilmann (L) and Al Simmons

Just before this crucial two-game finale, Al "Bucketfoot" Simmons, then a coach for the Athletics, swaggered into the Red Sox dugout, intent on planting doubts in the young hitter's mind. Four times in his career, Simmons, a lifetime .334 hitter, had averaged over .380, leading the AL in 1930 and '31. He and Cobb had always criticized Williams for being too selective at the plate. Approaching Ted, Al taunted, "How much you wanna bet you don’t hit .400?" Lesser men would have found the challenge from a bona fide Hall of Famer disconcerting, if not devastating. Not so Williams. If anything, it had the opposite effect, galvanizing Ted to the task at hand.

September 28 broke cold, damp and dreary at Shibe Park ? The crowd of 10,000 who braved the unpleasant conditions was rooting for the kid from Boston. In fact, they were pulling for him all the way. As he entered the batter's box, he heard home plate umpire Bill McGowan mutter: "To hit .400 a player has got to be loose." Ted had always enjoyed a great relationship with umpires; he respected them and never showed them up, and they, in return, marveled at his uncanny knowledge of the strike zone. Ted was undeniably loose. He singled sharply in his first at-bat, then homered to straightaway CF, and finished the game with two more singles and a walk. After game one, there was no way he could fail to hit .400, and many felt he would sit out the second game with a clear conscience. To the surprise and delight of the Philadelphia fans, however, Ted trotted to his position in LF. In game two, he confirmed his legend by doubling off the loudspeaker in RF and adding another hit. At the end of the day, he had accumulated six hits in eight at-bats, raising his average to .406. Heilmann had been right; Simmons dead wrong! Ironically, perhaps appropriately, in 1927, Heilmann had also battled down to the wire before capturing the AL batting title. Like Ted, he had refused to sit out the second game of a doubleheader to preserve his title. He picked up three hits to raise his average to .398 and win handily over the runner up, one Al "Bucketfoot" Simmons.

Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? Jimmy Breslin (1963)

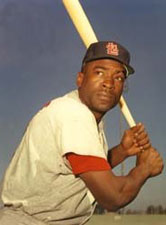

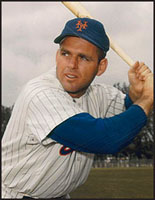

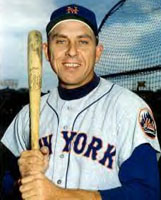

The Mets began their inaugural season as an expansion team in 1962 with Casey Stengel as their manager. They would finish with one of the worst records ever, 40-120. The Mets took the field against the St. Louis Cardinals. The team was dressed just as good as the Yankees. The Mets wore new gray flannel road uniforms ? Their spikes were shined, and their sweatshirts were laundry-clean. ? Roger Craig was the starting pitcher. In the first inning, Bill White of the Cardinals reached 3B. Craig eyed him carefully. Then he started his motion to the plate. The ball dropped out of Craig's hand. The umpire ruled it a balk and waved White across the plate. The Cards led, 1-0. The Mets' season now was officially shot. Before the night ended, the Cardinals got eleven runs. The Mets committed three errors, and the Cardinals stole three bases. Stan Musial ? got three hits. ... At forty-one, Musial had spent the winter thinking of retirement. But every time he came close to calling it a career, he thought of the Mets. A man could have a pretty good year in the big leagues just by playing against the Mets alone, Musial figured. So he stayed. He was right. He damn near won the National League batting title because of the Mets' pitching.    L-R: Roger Craig and Casey Stengel; Bill White; Stan Musial Two days later the Mets had their home opener at the Polo Grounds. Pittsburgh was the opposition. It was a dark, wet day, but anybody who meant anything in New York was at the Polo Grounds. There were Mayor Wagner and Jim Farley, there were Bill Shea and the late Mrs. John J. McGraw, Mrs. Payton [the owner] was in her box seat. Edna Stengel was on hand too. ? 12,447 spectators at the Polo Grounds. Like we said, everybody who meant anything showed up.

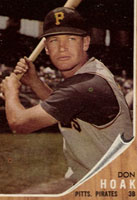

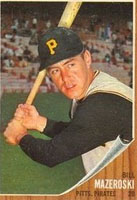

Unfortunately, so did the Mets. In the second inning, Don Hoak of the Pirates was on third and Bill Mazeroski was up with two out. Mazeroski hit a high fly into right center field. That was the third out. The moment Hoak saw the ball go harmlessly into the air, he put his head down and trotted from third to the plate. He wanted to get his glove out of the dugout. Mazeroski trotted to first. He was hoping somebody would bring his glove out of the dugout so he could go straight to his position at 2B. Out in the outfield, Richie Ashburn and Gus Bell of the Mets were trotting too. ... Ashburn called. He said he would make the catch. Bell did not answer. He kept waving Ashburn aside. Richie, an adult, did not argue. He stepped aside. Bell then waved himself aside. The ball hit the ground, took a bounce past them, and by the time they got it back to the infield Mazeroski was on third and Hoak was in the dugout. He had scored a run, but he did not really believe it.    L-R: Don Hoak, Bill Mazeroski, Gus Bell and Richie Ashburn The Mets fought back and by the eighth inning they had the game tied, 3-3. They also had Ray Daviault pitching. Daviault started the inning by walking Dick Groat. This is a very bad thing to do in a tight game. ? But at least Groat was not in scoring position. Daviault took care of this. He threw a pitch that went back to the stands, and Groat moved to second. An infield out allowed Groat to reach third. Daviault then took a full windup and threw his second wild pitch. Groat scored, and the Mets lost 4-3. ?

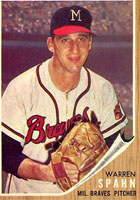

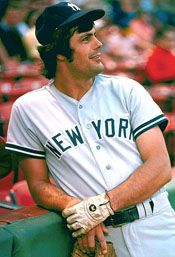

The Mets lost nine games before they finally got their first win of the season. During the losing streak, Stengel became a bit edgy. ? "The trouble is, we are in a losing streak at the wrong time," he said. "If we was losing like this in the middle of the season, nobody would notice. But we are losing at the beginning of the season and this sets up the possibility of losing 162 games, which would probably be a new record, in the National League, at least." ? the Mets then went out and shocked everybody by winning nine of their next twelve games. The highlight of the streak was the display of brute power the team put on in taking a doubleheader from the Milwaukee Braves at the Polo Grounds on May 12. In the first game, Warren Spahn was pitching for the Braves. He had the game won, 2-1, with two out in the ninth inning. A runner was on first. At bat was Hobie Landrith, the Mets catcher ? Spahn came down with the same curve ball that has made him one of the seven pitchers in modern times to win three hundred games. Landrith did not take back. Heroically, he went for the long ball. But the pitch fooled him, and the best he could produce was a soft fly ball that went 255' into RF. Part of the charm of the Polo Grounds, however, is the fact that a man pitching a game can, without turning his head, listen to fans in the RF stands ask each other for matches. They are exactly 254' away. This meant Landrith's drive had gone a full foot farther than necessary. As the ball went into the stands to give the Mets a 3-2 victory, the crowd of 19,748 came up with a roar. If a thing like this could happen, they were saying, then there is a chance for everybody. Landrith headed for 1B. He took one look at Cookie Lavagetto, coaching at first, and the two of them broke into laughter. Spahn took the defeat with the typical shrug-it-off of the real-life professional. When he got to the dressing room he said he wanted to kill himself.    L-R: Warren Spahn, Hobie Landrith, Gil Hodges Four hours and some minutes later, in the second game, Gil Hodges came to bat in the ninth inning of a 7-7 tie. There was one out and nobody on. Bob Fisher was pitching for the Braves. Hodges, swinging late, got a piece of the ball and hit it toward RF. This ball of his, smart observers insist, went farther than Landrith's. By more than five feet. This time the crowd was beside itself. The Mets won the game, 8-7, for their first sweep of a doubleheader. They did it with two HRs that only a Little Leaguer would own up to. And there are smart people today who insist it never happened.

Owls and Eagles Bob Forsch in Tales from the Cardinals Clubhouse:

Tales from the Yankee Dugout, Ken McMillan (2001) Piniella and Steinbrenner had the following conversation.

Lou, you can’t dress with hair that long. Why not? What has long hair to do with my ability to play? It's a matter of discipline. I just won't have it. If our Lord, Jesus Christ, came back down with his long hair, you wouldn't let him play on this team. Steinbrenner got out of his chair and had Piniella follow him across the street to a pool in the back of a motel. If you can walk across the water in that pool, Steinbrenner said, you don't have to get a haircut.

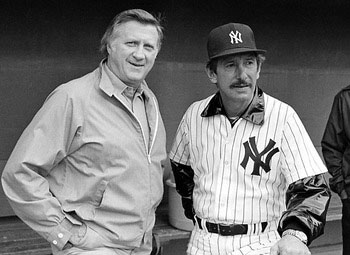

Point made. Piniella reported the next day with a nice and appropriate haircut. Steinbrenner thought Piniella would make a great manager someday so, in his usual course of taking action before thinking, he decided to make that point public. Of course, Steinbrenner already had a manager in place ? Billy Martin ? but with that tumultuous relationship it was probably best to have an ace up your sleeve.

George Steinbrenner and Billy Martin in 1985 Piniella got his first crack at managing the Yankees on an interim basis in July 1985. Martin had to be hospitalized when a doctor accidentally punctured his lung while trying to administer a muscle relaxant shot for Martin's aching back.

Steinbrenner phoned Piniella in Texas, where the Yankees were just finishing up a series with the Rangers, and told Piniella he would be taking over the club for a few days. To Piniella's dismay, Steinbrenner neglected to call Martin first, so Billy had to hear the news from someone else. The club flew to Ohio, and Piniella arrived at Cleveland Stadium early the next day to assume duties. He was informed by coach Doug Holmquist that Martin had called the clubhouse already and would have the lineup phoned in within an hour. The problems began when Piniella made his first mistake by failing to make out a lineup card ? he thought coach Gene Michael did that since he always posted it for the players. Martin kept in touch with Piniella via the telephone from his hospital bed in Arlington, Texas. With injured C Butch Wynegar serving as phone operator for a night, Martin called in each of the first three innings just to get updates and query Piniella on a few things. When the press caught wind of this after the game, their stories told of how Martin managed the Yankees from his hospital bed. The Yankees won the first two games under the Piniella/Martin setup and then lost three. Prank telephone callers tied up the phone line in the Yankees dugout, pretending to be Steinbrenner or Martin, infuriating the latter when his real calls couldn't get through. Players started questioning Piniella's moves. A fan yelled from the stands, "Is that your decision or is it coming from a hospital bed in Texas?" By the end of the Indians series, Piniella was so flustered he took a souvenir bat from his first win as manager and threw it into a urinal in the clubhouse. "I had been made to look foolish on the field and in the dugout," Piniella fumed. When he got home to New York, he told his wife he was quitting baseball altogether. However, calmer heads prevailed. Steinbrenner and Martin both asked Piniella to return as hitting coach.

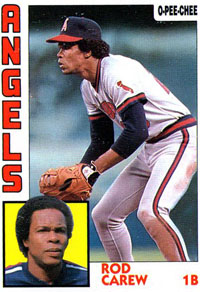

"Positioned for Greatness," Craig Ellenport, Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the Hall of Fame, Spring 2013

Rod Carew was not moved to first base because he was a liability as a fielder. But the slightly built Carew had taken a pounding after nearly nine full seasons as a 2B for the Minnesota Twins. Late in the 1975 season, manager Gene Mauch suggested the switch. "Guys came into second a heck of a lot harder in those days than they do today," said Carew, who first injured his knee in 1970 when a baserunner slid hard into second. He also recalled a couple of close call in '75 with the Athletics' Reggie Jackson and Sal Bando. "At the end of the year, Gene came to me and said, 'Pro, what would you think about making the move to first next season?' Gene wanted me in the lineup and I wanted to stay in the lineup, so I was all for it."

Carew recalled one game in particular, playing for the California Angels, when playing first really came in handy.

"I really had to go to the bathroom badly," he said. There were two outs in the inning, but the Angels pitcher walked a batter on 11 pitches, and then walked another on nine pitches. "I told 1B umpire Ken Kaiser I couldn't take it any more. He called a time out and the umpires conferred. Their conference lasted just long enough for me to run into the bathroom behind the Angels dugout and take care of my business. Of course, the next batter was retired on the first pitch." |