|

Auerbach Wanted No Part of Cousy

The History of the NBA in Twelve Games: From 24 Seconds to 30,000 Three-Pointers

Sean Deveney (2023) They needed a hat. Here they were, the most powerful men in NBA basketball, gathered in a room at the Park Sheraton Hotel on Seventh Avenue in New York City to determine the fates of players who had been rendered free agents after six franchises had been summarily contracted out of the struggling league, which had come together the previous year with a merger of the National Basketball League (NBL) and the Basketball Association of America (BAA).

On this fall evening, October 5, 1950, just 27 days before the start of the 1950–51 season, the eleven remaining team owners were finishing off the task of assigning players from the disbanded teams to their new clubs. It had gone smoothly—at least, that is, until it came to the rights to the final three players on the roster of the Chicago Stags, which had been a very good team the previous season, at 40-28, led by guards Max Zaslofsky and Andy Phillip. Zaslofsky was the top prize, a 24-year-old, 6-foot-2 guard from Brooklyn who had averaged 16.4 points the previous season, leading the league in free-throw shooting at 84.3 percent. Phillip, an Illinois local, was not a bad consolation, a deft passer who led the league in assists, with 5.8 per game.

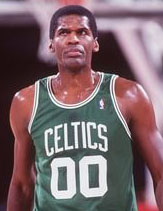

L-R: Max Zaslofsky, Andy Phillip, Bob Cousy, Red Auerbach Also up for grabs were the rights to rookie point guard Bob Cousy. Though he'd yet to play a pro game, there was buzz around Cousy because he had led Holy Cross to an unlikely NCAA championship two years earlier, and had helped the Crusaders to three straight tournament appearances. But Cousy, who was quick and lanky at 6-foot-1, did so with considerable showmanship, and the men of the NBA were split on whether his style could be adapted to the league.

The new coach of the Celtics, Red Auerbach, had not thought much of Cousy's fancy passes. The Celtics had caused an uproar among fans the previous April when they declined to take Cousy with the No. 1 pick in the 1950 NBA draft, just two days before they announced the hiring of Auerbach. Walter Brown, the affable owner of the Celtics, had been advised by Auerbach during the draft, and Auerbach wanted 6-foot-11 center Chuck Share out of Bowling Green. So Brown made Share the No. 1 pick that year. "I have no reason to believe," Auerbach said, "that Bob Cousy would make a good professional player." Later, Auerbach went even further in expressing his disdain for Cousy, saying, "I don't give a darn for sentiment of names. That goes for Cousy or anybody else. A local yokel doesn't bring in more than a dozen extra fans to your building. But a winning team does, and that's what I aim to have."

Cousy wound up going fourth in the draft to the Tri-Cities Blackhawks, Auerbach's previous employer. But the Blackhawks offered only $7,500 for Cousy's first year, and he had no interest in uprooting his life in Worcester, Massachusetts, to play in Moline, Illinois. Cousy had started a driving school and figured he could make more money with that than with what Tri-Cities was offering. The team traded his rights to Chicago, but Cousy had no idea he was one of the three Chicago Stags guards being tangled over among three East Coast teams, the Celtics, the Knicks, and the Philadelphia Warriors. Or, in Cousy's case, not being tangled over. Zaslofsky was given a price tag of $15,000, which all three teams were eager to pay to get a star of his caliber. Phillip would cost $10,000, and Cousy, $8,000. Auerbach had told Brown, "Get Maxie or nobody!" Ned Irish, from the Knicks, had zeroed in on Zaslofsky, too, hoping he could be a draw among New York's Jewish fan base. Philadelphia's Eddie Gottlieb also was badly in need of a guard, and wanted Zaslofsky.

Danny Biasone, meanwhile, was losing patience with the bickering. He was eager to wrap up the meeting so he could get back to Syracuse. Biasone, owner of the Syracuse Nationals, was a quiet but respected force among the cantankerous cohort of NBA owners.

Biasone developed a passion for basketball but did not have the kind of financial background to sustain a team, and the Nationals were a shoestring operation. In the summer of 1948, after having lost $62,000 on his venture in the previous two years, the league dispatched Leo F. Ferris to Syracuse to assist Biasone in the reorganization of the Nats. Ferris helped Biasone keep the team afloat by adding stockholders and helping to come up with marketing gimmicks, like raffling off a $ 500 silver fox coat (which drew an estimated 3,000 additional female fans).

L-R: Walter Brown, Ned Irish, Eddie Gottlieb, Danny Biasone, Maurice Podoloff With Ferris' help, the franchise got on to a more solid footing, and made one of the most important maneuvers in the early history of pro basketball—Biasone's Nats outbid the BAA for NYU star Dolph Schayes, a loss that forced the BAA to consider a merger. In August 1949, the two leagues came to an agreement, and Syracuse was one of the 17 teams welcomed into the new NBA.

Now, here was Biasone in a hotel among the NBA's magnates, and what the owners needed was a hat. The arguing over Zaslofsky had gotten nowhere, and it was late. Commissioner Maurice Podoloff gave a stern whack to the table and declared, "The only way to resolve this issue is to draw the players' names from a hat." At that, Biasone stepped forward and offered his fedora. It was from this hat that the raffle that would change the future of the NBA took place, with Irish and the Knicks getting Zaslofsky, Phillip going to Philadelphia, and Cousy to Boston. Walter Brown blanched at the thought of having to explain to Auerbach that he'd just gotten stuck with the "local yokel." But eventually, Auerbach would warm up to Cousy, who became the greatest point guard in the early days of pro basketball.

Biasone, meanwhile, took one of the most important hats in NBA history, popped it back onto his head, and left the room.

Alcindor Meets Wilt

Giant Steps: The Autobiography of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar,

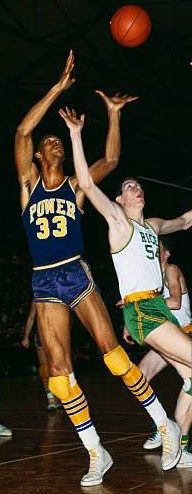

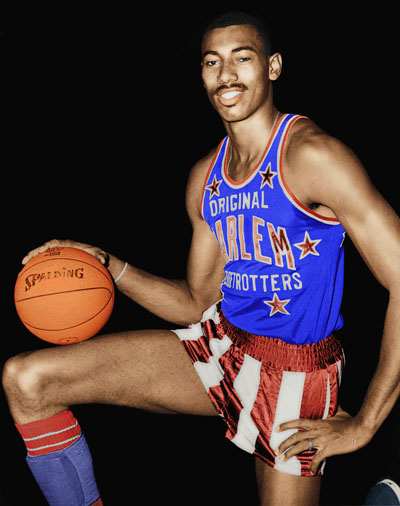

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar & Peter Knobler (1983) Lew Alcindor grew up in New York City and attended Power Memorial Academy where Jack Donohue was the head basketball coach. My father took me to the old Madison Square Garden when Wilt Chamberlain was with the Harlem Globetrotters, and I saw him dunk a few, but the play was nothing special. Coach Donohue took me to the Garden when Wilt was playing for Philadelphia, and I watched him grab every rebound, dominate the game, and get beaten by Bill Russell and the Celtics. But I never really felt Wilt's power until I saw him up close.

The first time was when I was fifteen, a freshman in high school, six feet ten inches tall. I'd gone up to the St. Nicholas project on 129th Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues where the Rucker Tournament was held, to watch. I was too timid, skinny, and nowhere near good enough to get in a game–and besides, CHSAA rules prohibited high school athletes from participating–but I needed to know how this thing was really played. I was up there with my friend Wesley Carpenter, and we spotted Wilt, all of twenty-five years old and a Rucker celebrity, at midcourt taking off his street clothes to reveal his tank-top and uniform shorts underneath. There were only two men for me to be like in the NBA, Wilt and Russell (clearly I couldn't be Oscar Robertson, Elgin Baylor, or Jerry West), and here was one of them, not so very much larger than I was, standing on the same blacktop. I didn't move, couldn't find anything to say that wasn't dumb. But Wesley was an outgoing guy, had a lot of nerve. He said, "Come on, let's just go meet him." I would never have done it alone.

Wilt saw us coming. He had just completed his third year in the NBA and was no newcomer to Harlem, so he'd developed his own style of dealing with strangers. In this crowd, in this setting, he knew he was being approached by connoisseurs. My anxiousness no doubt showed in my eyes, and he could have pulled the gruff withdrawal that one too many uninvited well-wishers can bring on, but though I was too young to offer him any real challenge, I was one of the few people in the world who didn't have to look up to him.

Wes decided he would make the introductions since it was obviously beyond me. I told Wilt my name, and he said, "Oh yeah, I heard of you. You're that young boy that plays for the Catholic school, supposed to be getting good." Wilt had heard about me! When I thought about it later I got all charged up, but right then I was cool.

"I really admire the way you play the game," I told him, shaking his hand. He looked me up and down like a trainer examining a racehorse. "You've got good legs," he said. I looked down, trying to see what Wilt saw in me. "I wish I had legs like that," he said. I was thrilled–Wilt had taken notice of me!–and when the conversation died I just said, "Nice to meet you," and turned off into the crowd. From then on when I saw him at the Rucker I'd go up and have a few words.

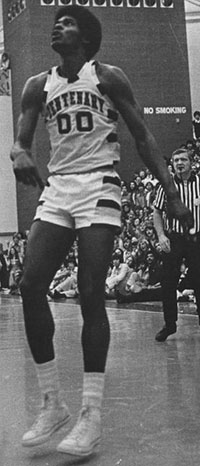

L-R: Lew Alcindor, Wilt Chamberlain, Connie Hawkins In 1964 Wilt had his own Rucker team. Twice an All-American, I still wasn't playing up there, but I saw some amazing basketball. Wilt's team was playing one afternoon against an all-star lineup from Brooklyn. Connie Hawkins led it, perhaps the greatest ballplayer of all time, totally in his element on the asphalt.

Connie played a lot of street ball, and I'd go watch him and not only learn new moves, I'd get taught a whole new concept of the game. The Hawk would snare a rebound and swoop downcourt as each of his teammates circled in their own improvised patterns. He would fake his man a couple of times, as if testing his engines, and then gun it. Palming the ball, waving it around in one of his huge hands, he'd take off some 20' out and glide to the basket like a Black Phantom, then hang, hesitate while two or three defenders each took their separate shots at him, somehow circle underneath the basket, let go the ball, and put it in off the backboard–with English. All he needed to top it off would've been a victory roll. No one had ever done that before. No one had even thought of doing it.

Connie was only about twenty when I was in high school, and already he was an endangered species. He had gotten involved in a betting scandal (from which he was ultimately exonerated), so his pro career was stunted and his ambition damaged, but he was an amazing athlete. His physical gifts were unique, and he had such a natural grasp of basketball's mental demands that he never had to work very hard on his game. He practiced his ball handling and his shot, but if he had worked on his wind and lifted some weights, and had been given the opportunity to play when it was his time to play, he would easily have been recognized as the greatest ever.

On his team this day were Pablo Robertson and Jackie Jackson. Pablo was a magician with the ball: he would dribble through people's legs and back again, slice into impenetrable defenses, and make passes that were not simply true, they were truth. Jackie was six-five, maybe six-six, but he could leap so that his arm reached a foot-and-a-half, two feet above the rim. Their team and Wilt's went at it.

Wilt posted himself low, backed in, used his massive shoulders and trunk to batter whoever was in his way, then turned and shot his trademark fall-away jumper. This tended to work pretty well for Wilt; he was averaging better than 40 points per game in his NBA career at the time.

But Jackson was serious. This wasn't just a game; this was all that was real. With his Genghis Khan mustache and a shaved head, he knew that the meaning of life hung on the rim. As Wilt started his fade, Jackson came running on a sharp diagonal from all the way the other side of the court. He leaped, looked like he was climbing, and at the top of his arc, his arm above the white box over the rim at the 11' mark, he mashed the ball right as it reached the backboard. Pinned! Might have been goal-tending in the NBA, but they didn't play that shit here. The crowd stomped a soulful celebration as Jackson pulled the ball down and shot it out to Hawk, who was in midflight to the hoop. It was the most amazing play I've ever seen on the court, and the whole place went crazy.

It was like that all afternoon. Pablo would dribble through everybody. The Hawk would come down and shoot in Wilt's face, right over his hands, or get him up in the air and make the sweet pass around him. They put it to him for three quarters, really made Wilt mad. Finally, of course, Wilt had to get every rebound, which he did. He refused to be beaten, and every time he got the ball inside, which was often since it was his team, it was a dunk. Ten times in a row. Pass to Wilt, dunk. Pass, dunk. Shot, rebound, dunk. Total domination. He'd take people up with him. One time I can remember like a photograph: His head was almost above the rim; there were players draped all around his neck, and it looked for all the world like the end of Moby Dick with Gregory Peck lashed to his prey, beckoning his crew to the quest. Wilt Chamberlain as the White Whale.

I got close to Wilt that summer. He lifted weights at the 135th Street Y where our journalism headquarters were, and I made a point of dropping in whenever I heard he was around. Once when I was shooting the ball in the gym, Wilt came by and we started playing some HORSE, matching shots, him trying to hit some hooks and me taking the fadeaways. We didn't go one-on-one, I wasn't even tempted, but at least now I had a speaking relationship with him.

|

Robert Parish's Road to the NBA - 1

The Big Three: Larry Bird, Kevin McBride, and Robert Parish:

The Best Frontcourt in the History of Basketball, Peter May (1994)

The next year, Parish arrived at Union and Kidd was there, ready for his new center. But his new center, now 6-4, still wasn't interested. Parish had told Kidd he would come to practice, but when the club gathered there was no sign of him. Kidd reminded Parish of his agreement and mildly admonished the youngster that he had better not continue to be a no-show. Parish continued to be a no-show. Kidd then led Parish into the locker room and produced a small, half-inch-thick oak paddle, which the shop teacher had made for him. He made Parish bend over so he could get "better leverage." Then Kidd said, "I warmed his pants real good. He rubbed his backside when I was finished." And the next time the junior high school basketball team gathered, Parish was there. Kidd was so pleased he even let Parish wear cutoff blue jeans instead of basketball shorts. There weren't any around that fit, anyway. "He gave me a couple of good, strong whacks and said, 'I expect to see you here tomorrow,'" Parish said. "And then I decided to come out. Back then, you could do that stuff." "We had our way with the students back then," Kidd said. "The parents expected you to do it and never complained or asked questions." Now he had Parish. But he soon began to wonder if this was a case of "Be careful what you wish for because you might get it." Parish wasn't kidding about his utter lack of basketball skills or knowledge. He may as well have spent his first twelve years in Antarctica. "I really didn't have a clue about the game," Parish said. "They threw me the ball and I started to run with it. And that's only when I was able to catch it. A lot of times it would hit me in the face or go right through my hands. I mean, I was bad." Kidd said Parish's skills were as bad as Parish described them. Maybe worse. He was forced to use Parish only in late-game, blowout situations. In his first year of organized basketball, Robert Parish, perennial NBA All-Star and future Hall of Famer, was strictly a garbage-time player. "I was so disappointed," Kidd said. "I'm saying to myself, 'Here is a boy that could go places, but he just doesn't have the skills. Or the potential.' He couldn't catch it. He couldn't dribble it. He was clumsy. He had hard hands and no coordination and I almost gave up on him. I did everything I could. Jump-roping drills. Everything. I'd make him take a basketball home. Then he started to show a little promise at the end of the seventh grade, and after playing all summer in the city he came back and was a totally different player. He was phenomenal." So good, in fact, that Parish played for Kidd only one more year before he was promoted to the Union varsity in the ninth grade. As a freshman at Union, he led the school to the state semifinals. He did the same thing as a sophomore. But he did it while playing only with black teammates and only against all-black competition. The following year, a court order changed everything. In an attempt to integrate the schools, Union High was closed and turned into a career vocational center. Its student body was dispersed, mostly to Woodlawn. Few were happy with forced integration. For the previous two years, Shreveport had had a "freedom of choice" option that allowed blacks to attend the white schools. But few did. Before that, blacks went to one of three schools (Union, Bethune, or Booker T. Washington) and whites attended one of four schools (Woodlawn, Fair Park, Captain Shreve, and Byrd). The school system consisted of two entire, separate, and insulated worlds whose paths rarely crossed. Cliff Roberts, the point guard at Woodlawn in the first year of integration, had never heard of Woodlawn until they played together at Woodlawn. Freedom of choice had, however, allowed a trailblazer named Woodlawn to becom one of the first blacks to play for a previously all-white school in Shreveport or anywhere in northern Louisiana. Russell had to a wait a year at Woodlawn before he could play, but when he did his team won the state title in 1968-69. He played with Parish in college and later coached Woodlawn to a state title. "It could not have opened up without Melvin Russell," Woodlawn coach Ken Ivy recalled. "By the time Robert got there, we had been through all the stuff - people refusing to feed us, things like that. Melvin made it possible. And it was kids like Robert that came along after that that made it go." Parish didn't want to leave Union. It was a short walk from home. He was comfortable there, but it was closing and Woodlawn was more than a mile away. "None of us wanted to be there," Parish said. "It was a huge transition. I would have preferred to stay where I was. I didn't like being broken up and separated. I resented that." ... "It was a very, very traumatic year for everyone, blacks and white," said Roberts. "The blacks didn't like it. The whites didn't like it. We had never been exposed to blacks and they had never been exposed to whites. There was some violence, but not too much. On the team, it was OK. But beyond that, there was no camaraderie whatsoever. Basketball was the only time we were together. And it was hard for me because none of my friends from Fair Park was there. I became a Woodlawn Knight. But I was still a Fair Park Indian at heart and always will be." Continued below ...

|

Robert Parish's Road to the NBA - 2

The Big Three: Larry Bird, Kevin McBride, and Robert Parish:

The Best Frontcourt in the History of Basketball, Peter May (1994)

Read Part 1 ...

The Best Frontcourt in the History of Basketball, Peter May (1994)

Read Part 1 ...

Robert Parish transferred to Woodlawn High School in Shreveport his junior year (1970-71) because of court-ordered integration.

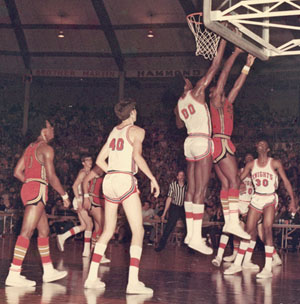

The Woodlawn team was awesome. All five starters from the Union team were on it, including Parish and a 6-1 wunderkind named William Wilson, who, G Charlie Roberts recalled, was by far the best player on the team. Roberts was a starter from Fair Park. And Woodlawn had four returning starters from its team the previous year. Roberts was one of four whites on the team. The next year, two years after integration, the basketball team would have no whites.

While Wilson was dazzling - he eventually went to Southern University but dropped out - Parish, who was closing in on seven feet, was the certifiable star. The Woodlawn Knights were almost unbeatable: they went 36-2 in his junior year, the best year in Shreveport prep history. Most of their home games were played not at the high school but at the Hirsch Coliseum, miles away, because authorities were worried about crowd control after the integration edict.

The 1970-71 was, by all accounts, a superior team to the one the following year, although it failed to win the state title. Parish, who practiced his rainbow jumper by shooting over a broomstick held by coach Ivy, broke the school scoring recod for a single season (881 points) despite playing in the second half in only eight games. "The scores were so lopsided," Coach Ken Ivy said. "He played his half and that would be it. He didn't care if he scored thirty points or if he scored five points. As long as we won. But I never liked to score a hundred points on anyone because it can come back to haunt you."

Woodlawn's biggest win came in the state semifinals, where it beat Booker T. Washington of New Orleans, which featured future (ABA and NBA) pro Bruce Seals. Woodlawn trailed by 11 and Parish fouled out, but the team rallied to win, 79-73. Woodlawn then came up flat against an inferior team from New Orleans, Brother Martin, and lost the final, 65-62. ... Parish got into foul trouble in that game, too. "The referees had absolutely no clue how to call a game with a seven-footer in there," Ivy said. "He only played a few minutes in that game. He'd block a shot, they'd call a foul."

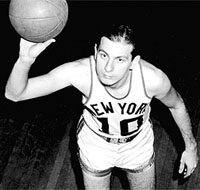

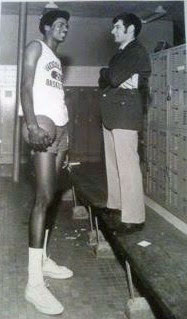

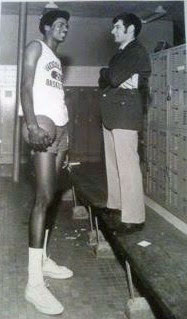

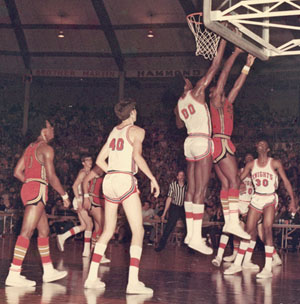

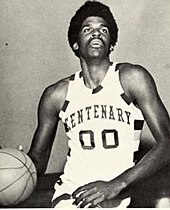

L: Robert Parish at Woodlawn; R: Parish (00) tries to block the shot of

Gabe Williams of Brother Martin in the 1971 Louisiana state final.

Woodlawn got redemption the following year. Before the season started, Parish and Ivy huddled and it was agreed that Parish would play at least three quarters in each game because it was critical to his development. All Parish did was average 30.7 points and 19.9 rebounds a game as Woodlawn went 35-2 and won the state title. In one game in Lake Charles, Parish scored 52 points to set a school record. He established the mark only because the team manager mentioned it to Ivy when Parish was given a rest with 48 points and the team comfortably ahead.

"I told Robert to go out there, get the record, and then get off the floor," Ivy said. "I didn't want to keep him out there. The other coach was a good friend of mine. Well, sure enough, we put Robert back in after a time-out and what does he do? He throws the ball back out after getting it inside. So I call another time-out and tell him, 'Robert, get the four points, will you?' He scored a couple quick ones and that was that."

Woodlawn was almost like a road show that season. At one point the team was 17- and had played only four home games. For good reason, no one wanted to play the team at its own gym or even at Hirsch. That was as close to an automatic loss as you could get. So on Woodlawn's many road trips Parish would fold himself up and climb into Ivy's Volkswagon as the two drove to games. "He went with me," Ivy said, "because I wanted to make sure he got there."

One of Woodlawn's two losses that season came against Hughes Springs, Texas, 56-54. Ivy said it was the worst-refereed game he'd seen in thirty years of coaching. Another visitor that night, Indiana coach Bobby Knight, later told Ivy the same thing.

"It was unbelievable. At that time I'd play anybody, anywhere. We'd drive all over east Texas," Ivy said. "Well, in the first two minutes of the game, Robert picked up three fouls and he still hadn't touched anyone. And the referee making the calls is someone I'd never seen before. Robert probably played about seven minutes that night. Every time he moved, there was a foul. All five of our starters fouled out and we're still only down two points at the end. Then one of our guys gets called for traveling while he's still dribbling the ball. They get the ball back and run out the clock."

The postgame scene was almost embarrassing. Even the fans sensed that Woodlawn had been shafted, and they consoled the players afterward. The Hughes Springs players apologized and shook hands. Knight came up to Ivy and said, "I've recruited in 28 states and I thought I had seen everything. But I don't think I ever saw anything like I saw tonight."

Parish looked up at Ivy after the game and said simply, "Do we have to count this one, coach?" The coach found out later that the unknown referee was not a referee at all, but a friend of the Hughes Springs coach who had been visiting over the holidays and had been pressed into service due to a still unknown "emergency." Hughes Springs was scheduled to play Woodlawn later that season, but - surprise - canceled the game.

"I saw Bobby Knight the next year," Ivy said. "He was across the room. And as soon as he saw me, the first thing he said was, 'Ken, have you been to Hughes Springs, Texas, lately?'"

Woodlawn rolled through the first three games of the state tournament, including another victory over Booker T. Washington/New Orleans in the semifinals. This time, however, Woodlawn eked out a 50-49 victory in the finals over Rummel. Again, Parish's contributions were limited by foul trouble. "The officials were trying to make the game even," Parish said. "That's why I was always in foul trouble. Same thing in college. They try to restrict the big man. But the win was satisfying, especially after the year before."

The Woodlawn team was awesome. All five starters from the Union team were on it, including Parish and a 6-1 wunderkind named William Wilson, who, G Charlie Roberts recalled, was by far the best player on the team. Roberts was a starter from Fair Park. And Woodlawn had four returning starters from its team the previous year. Roberts was one of four whites on the team. The next year, two years after integration, the basketball team would have no whites.

While Wilson was dazzling - he eventually went to Southern University but dropped out - Parish, who was closing in on seven feet, was the certifiable star. The Woodlawn Knights were almost unbeatable: they went 36-2 in his junior year, the best year in Shreveport prep history. Most of their home games were played not at the high school but at the Hirsch Coliseum, miles away, because authorities were worried about crowd control after the integration edict.

The 1970-71 was, by all accounts, a superior team to the one the following year, although it failed to win the state title. Parish, who practiced his rainbow jumper by shooting over a broomstick held by coach Ivy, broke the school scoring recod for a single season (881 points) despite playing in the second half in only eight games. "The scores were so lopsided," Coach Ken Ivy said. "He played his half and that would be it. He didn't care if he scored thirty points or if he scored five points. As long as we won. But I never liked to score a hundred points on anyone because it can come back to haunt you."

Woodlawn's biggest win came in the state semifinals, where it beat Booker T. Washington of New Orleans, which featured future (ABA and NBA) pro Bruce Seals. Woodlawn trailed by 11 and Parish fouled out, but the team rallied to win, 79-73. Woodlawn then came up flat against an inferior team from New Orleans, Brother Martin, and lost the final, 65-62. ... Parish got into foul trouble in that game, too. "The referees had absolutely no clue how to call a game with a seven-footer in there," Ivy said. "He only played a few minutes in that game. He'd block a shot, they'd call a foul."

L: Robert Parish at Woodlawn; R: Parish (00) tries to block the shot of

Gabe Williams of Brother Martin in the 1971 Louisiana state final.

"I told Robert to go out there, get the record, and then get off the floor," Ivy said. "I didn't want to keep him out there. The other coach was a good friend of mine. Well, sure enough, we put Robert back in after a time-out and what does he do? He throws the ball back out after getting it inside. So I call another time-out and tell him, 'Robert, get the four points, will you?' He scored a couple quick ones and that was that."

Woodlawn was almost like a road show that season. At one point the team was 17- and had played only four home games. For good reason, no one wanted to play the team at its own gym or even at Hirsch. That was as close to an automatic loss as you could get. So on Woodlawn's many road trips Parish would fold himself up and climb into Ivy's Volkswagon as the two drove to games. "He went with me," Ivy said, "because I wanted to make sure he got there."

One of Woodlawn's two losses that season came against Hughes Springs, Texas, 56-54. Ivy said it was the worst-refereed game he'd seen in thirty years of coaching. Another visitor that night, Indiana coach Bobby Knight, later told Ivy the same thing.

"It was unbelievable. At that time I'd play anybody, anywhere. We'd drive all over east Texas," Ivy said. "Well, in the first two minutes of the game, Robert picked up three fouls and he still hadn't touched anyone. And the referee making the calls is someone I'd never seen before. Robert probably played about seven minutes that night. Every time he moved, there was a foul. All five of our starters fouled out and we're still only down two points at the end. Then one of our guys gets called for traveling while he's still dribbling the ball. They get the ball back and run out the clock."

The postgame scene was almost embarrassing. Even the fans sensed that Woodlawn had been shafted, and they consoled the players afterward. The Hughes Springs players apologized and shook hands. Knight came up to Ivy and said, "I've recruited in 28 states and I thought I had seen everything. But I don't think I ever saw anything like I saw tonight."

Parish looked up at Ivy after the game and said simply, "Do we have to count this one, coach?" The coach found out later that the unknown referee was not a referee at all, but a friend of the Hughes Springs coach who had been visiting over the holidays and had been pressed into service due to a still unknown "emergency." Hughes Springs was scheduled to play Woodlawn later that season, but - surprise - canceled the game.

"I saw Bobby Knight the next year," Ivy said. "He was across the room. And as soon as he saw me, the first thing he said was, 'Ken, have you been to Hughes Springs, Texas, lately?'"

Woodlawn rolled through the first three games of the state tournament, including another victory over Booker T. Washington/New Orleans in the semifinals. This time, however, Woodlawn eked out a 50-49 victory in the finals over Rummel. Again, Parish's contributions were limited by foul trouble. "The officials were trying to make the game even," Parish said. "That's why I was always in foul trouble. Same thing in college. They try to restrict the big man. But the win was satisfying, especially after the year before."

Continued below ...

Robert Parish's Road to the NBA - 3

The Big Three: Larry Bird, Kevin McBride, and Robert Parish:

The Best Frontcourt in the History of Basketball, Peter May (1994) As he finished his record-setting career (at Woodlawn High School in Shreveport), Robert Parish had coaches around the country drooling, hoping to land him for college. Jerry Tarkanian, then the coach at Long Beach State, had seen Parish play at Woodlawn when his team arrived in town to play Centenary. He told assistant coach Riley Wallace of Centenary, "If that kid ever gets out of town, they should fire you all." Wallace was concerned about Houston, which had successfully recruited Lou Dunbar from Minden, outside Shreveport. He remembered being excited when he was invited to Dunbar's home for the letter of intent signing, thinking Centenary had bagged a good one. He quickly discovered that was not the case when he entered the house and saw Houston coach Guy Lewis there along with a horde of cameras.

But Wallace told Ada Parish that Houston had a reputation for not graduating its players, and Ada Parish wanted her son to graduate. He would be the first in the family to do so. Countless other schools drifted in and out of the picture, and Wallace visited the Parish home one day to ask where Centenary stood and who was behind the decision-making process.

"Honey, I'm going to tell you something right now," Ada Parish said sternly. "Robert Parish is a man and is making his own decision." ...

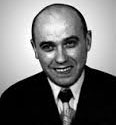

L: Robert Parish, Riley Wallace, Bob Knight, David Berst Parish eventually whittled his choices down to five schools: Centenary, Indiana, Florida State, Jacksonville, and Illinois State.

Indiana coach Bob Knight was one of many persistent pursuers of Parish and got Parish and Ivy to make a visit to Bloomington. The weather was horrible and nothing Knight could do could make up for Mother Nature.

During the interview, Knight sat Parish down and asked him what he wanted. "How much money do you want a month?" Knight asked. "What kind of car? What kind of clothes?" Parish, typically, said nothing, though he was wondering where this all was leading. He and Ivy had had an agreement that any time a coach promised something that looked shady, he would tell the coach without mentioning names. "The reason I'm asking you if you want all of this is because you'll get none of it if you come to Indiana," said Knight. "You come here, you come here because you want to play for a national championship. If you want that other stuff, I can give you some phone numbers because I know guys who can and will give you that stuff."

Knight also told Parish something more important and more critical to Parish's short-term future. If was something Parish would hear elsewhere: we can't take you on scholarship because your grades and test scores are too low.

The NCAA was watching Parish closely. The organization knew he was being heavily recruited and wanted to make sure everything was on the up-and-up. It dispatched a young employee named David Berst to oversee the matter. He met with Parish at Woodlawn and, sitting in the bleachers after a faculty game, advised him on what was proper and what was not. "I interviewed him because he was a seven-footer and in those days we all tried to figure out if there might be a problem," Berst said.

...

Parish decided to go to hometown Centenary.

Centenary and Parish were, are, and always will be an utterly unfathomable mix. There is no other instance of such a valuable high school commodity – he was, at worst, the number two recruit in the country – selecting a school so utterly devoid of basketball tradition or excellence. There simply is nothing that even comes close. (Bob Lanier and St. Bonaventure Bonnies might be the closest.)

"It was totally his decision," his mother said. "All I told him was that he could go all across the country, but what he might need the most would still be in his own backyard." Parish was an incorrigible homebody. Had he lived in Monroe, he probably would have gone to Northeast Louisiana.

In Parish's days, Centenary was the smallest Division I school in the country - its student body consisted of only 700 students. Today, it has 1,100 students. It is the oldest private liberal-arts-college west of the Mississippi and has a beautiful campus of brick Georgian buildings and flowering magnolia trees. It also has a 3,000-seat gym, the Gold Dome, which opened the year Parish arrived. ...

Curiously, however, despite its reputation as an academic institution, Centenary's procedures for admitting freshmen scholarship athletes were among the most lenient and favorable in the country. And that played a big part in the Parish courtship.

In those days, an incoming freshman had to predict to a 1.6 grade point average (out of 4.0) to be eligible for an athletic scholarship. The school arrived at this number by taking the player's grades, high school rank, and test scores, throwing them into an education Veg-o-Matic, and getting a numerical result.

To this day, there are two very different views on Parish's projected eligibility. He says it was not a problem, and Wallace, who recruited Parish, concurs. The NCAA, however, did not see it that way, nor did the federal courts. The disagreement occurred when Centenary converted Parish's ACT score to an SAT number after being advised repeatedly, in writing and by phone, that such conversions were not allowed and would result in Parish's being declared ineligible.

The killer wasn't Parish's grades; he had a 2.1 average at Woodlawn. It was his score on the ACT. ... Parish took the ACT twice. His highest score was an 8, which put him in the first percentile for men. In other words, 99 percent of the male students who took the test did better. The low score was a red flag to several schools, which decided there was no way Parish could be eligible or predict to a 1.6. Indiana was one of those. Florida State told Parish he would need a 21 on the ACT to project to a 1.6 and suggested he take it again. But Parish was tired of taking tests, and Wallace agreed, calling him "gun-shy."

Another option Parish did not consider was attending a state school - LSU or Northeast Louisiana were two possibilities - which he could have done merely by graduating from high school. And he could have become eligible for a scholarship at a state school once he had an academic track record. But Parish said he could not afford to pay for college, even a state school.

Centenary, which saw a chance to land a premier player and knew that Parish wanted to remain close to home, went hard after the homegrown talent. As it had with many athletes before - including twelve the previous year, when conversions also were not allowed - Centenary converted Parish's ACT score to an SAT score. The problem was that Parish was being watched, and so Centenary was playing with the big boys. No one had cared or noticed before, and Centenary had never revealed anything, either.

To be continued ...

|

Robert Parish's Road to the NBA - 4

The Big Three: Larry Bird, Kevin McBride, and Robert Parish:

The Best Frontcourt in the History of Basketball, Peter May (1994) Read Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 The NCAA had ruled in 1969 that, effective May 1970, two years before Parish enrolled at Centenary, conversion tables no longer would be allowed. All NCAA member institutions, including Centenary, were informed in writing. In June 1972, with the courtship of Parish well under way, the NCAA again wrote to remind Centenary that conversion tables were a no-no. That missive came after (Coach Riley) Wallace told (NCAA representative David) Berst that Centenary was converting the ACT score to an SAT number, as it had before without recrimination or punishment.

Berst again warned the school in August, a week before Centenary announced that it had landed Parish. Berst said he even suggested that Parish take the SAT so there would be no problem. Parish, however, was never told about the eligibility questions or advised by Centenary to either retake the ACT or try the SAT. He didn't hear anything until he and four other basketball players admitted via the conversion table method were well into their freshman year, after the basketball team began practice but before it had played any games.

"The school president came to us and told us that the NCAA was being picky," Parish said. "I did not know anything about them [the conversion tables] being outlawed. They also said the NCAA said nothing about it."

That simply is not the case. Centenary was warned. It sipmly chose to ignore the NCAA, and it did not take advantage of any appellate proceedings within the NCAA guidelines. On January 9, 1973, the NCAA lowered the boom, putting Centenary on indefinite probation. If the players were quickly ruled ineligible, the probation would last two years, but if the players continued to play, the sanctions would stay in effect until two years after they left. Included in the sanctions were bans on postseason play and television appearances.

Sports Illustrated did a piece on Parish in 1976. The New York Times called the school "unknown and unwanted." None of that would have been forthcoming had Parish been declared ineligible. As one college scout observed during Parish's senior year, "Without Parish, they would not be on probation, but no one would have ever heard of them, either." |

Kobe Turns Pro - 1

Three Ring Circus: Kobe, Shaq, Phil and the Crazy Years of the Lakers Dynasty

Jeff Pearlman (2020)

Jeff Pearlman (2020)

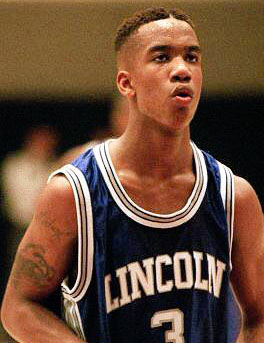

On July 7, 1994, Kobe Bryant reported to the campus of Fairleigh Dickinson University in Teaneck, New Jersey for a week of high-level basketball most presumed he would not be ready for. He was one of four high school juniors in attendance, and the majority of the buzz was directed toward a pair of New York City guards— Stephon Marbury of Lincoln High and Shammgod Wells from New York City's La Salle Academy. To be a lesser-known player at ABCD is to shuffle with one's head down, with eyes glued to one's sneakers. It's intimidating, it's jarring—"You're there with guys who can do amazing things," said Holloway. "You're the best where you're from. But going there is an eye-opener."

From day one, Bryant walked as if he belonged. He played hard, played fast, refused to kneel before Marbury or Wells or the fantastic Tim Thomas of Paterson, New Jersey. He wore three chips on his shoulders— the kid from Italy nobody worried about, the kid from suburbia nobody worried about, the son of an NBA alum. The star of the camp was Marbury, who at one point shook Holloway, rose from the free throw line, and carried his 6-foot-1 body toward a 6-foot-9, 240-pound shot blocker named Patrick Ngongba. With an audible grunt, Marbury dunked in the giant's face, landed, screamed "Wooooooo!," grinned from cheek to cheek, walked the full length of the court, out the gym, and onto the bus that ferried participants to and from the facility.

The other players hooted and hollered with glee.

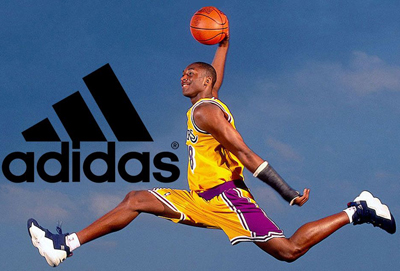

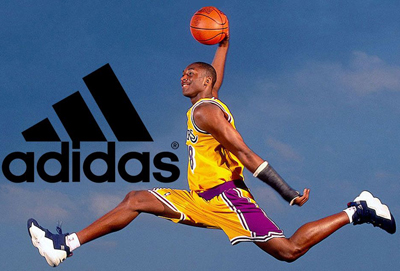

Bryant joined the audible circus, but inside, jealousy consumed the teen. That should have been him. That would be him. When the camp concluded and Marbury and Thomas were named most valuable players, Bryant approached (Sonny) Vaccaro (who ran Adidas's ABCD summer camp) and tapped him on the shoulder.

"Mr. Vaccaro," he said, "I want to apologize to you."

"What do you mean?" Vaccaro said.

"I'm just telling you, next year I'll be the MVP here. I'm sorry I let you down."

Vaccaro was speechless. Kobe Bryant owed him no apology. But the integrity and intensity were unlike anything he'd seen in ABCD history. "I've never forgotten that," he said years later. "His mindset was not 'Hey, thanks for having me. I've enjoyed the opportunity and I look forward to returning.' It was 'Fuck that. I'm gonna be MVP.' Call it what it is— confidence, arrogance, self-assurance. He knew he'd be great, and at that moment I knew he'd be great. And at that moment— that very moment— I also knew Adidas would be in the market for Kobe Bryant."

From day one, Bryant walked as if he belonged. He played hard, played fast, refused to kneel before Marbury or Wells or the fantastic Tim Thomas of Paterson, New Jersey. He wore three chips on his shoulders— the kid from Italy nobody worried about, the kid from suburbia nobody worried about, the son of an NBA alum. The star of the camp was Marbury, who at one point shook Holloway, rose from the free throw line, and carried his 6-foot-1 body toward a 6-foot-9, 240-pound shot blocker named Patrick Ngongba. With an audible grunt, Marbury dunked in the giant's face, landed, screamed "Wooooooo!," grinned from cheek to cheek, walked the full length of the court, out the gym, and onto the bus that ferried participants to and from the facility.

The other players hooted and hollered with glee.

Bryant joined the audible circus, but inside, jealousy consumed the teen. That should have been him. That would be him. When the camp concluded and Marbury and Thomas were named most valuable players, Bryant approached (Sonny) Vaccaro (who ran Adidas's ABCD summer camp) and tapped him on the shoulder.

"Mr. Vaccaro," he said, "I want to apologize to you."

"What do you mean?" Vaccaro said.

"I'm just telling you, next year I'll be the MVP here. I'm sorry I let you down."

Vaccaro was speechless. Kobe Bryant owed him no apology. But the integrity and intensity were unlike anything he'd seen in ABCD history. "I've never forgotten that," he said years later. "His mindset was not 'Hey, thanks for having me. I've enjoyed the opportunity and I look forward to returning.' It was 'Fuck that. I'm gonna be MVP.' Call it what it is— confidence, arrogance, self-assurance. He knew he'd be great, and at that moment I knew he'd be great. And at that moment— that very moment— I also knew Adidas would be in the market for Kobe Bryant."

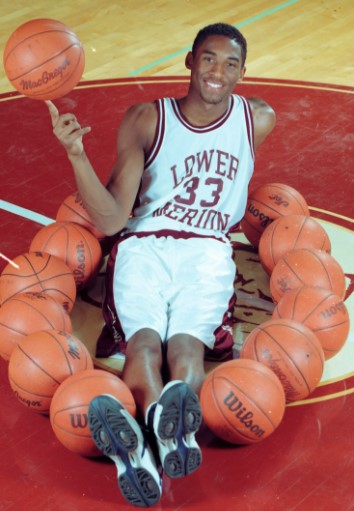

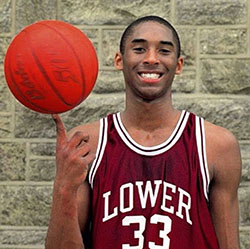

L-R: High schoolers Kobe Bryant and Stephon Marbury, Sonny Vaccaro

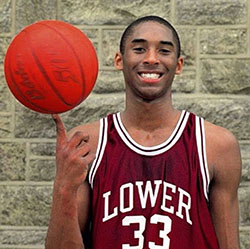

Over the next two years, Kobe Bryant went from here to HERE. As a junior at Lower Merion High School in Ardmore PA, he averaged 31.1 points, 10.4 rebounds, and 5.2 assists and was named Pennsylvania's Player of the Year. Everything about Bryant was ferocious. He would arrive at the school gymnasium at 5 a.m. to shoot on his own, then stay two hours after practices in the evening. What he lacked in social skills he made up for with doggedness. Lots and lots and lots of doggedness. "People think his athleticism was the most impressive thing— and they're wrong," recalled Emory Dabney, the Lower Merion point guard. "It was the drive. He wasn't psychotic, but he bordered on psychotic." In particular, Dabney recalled one 95-degree summer day when he and his star teammate worked out on the track at nearby St. Joseph's University, then went across the street to Episcopal Academy to play pickup. "Kobe would get in the car after running and turn the heat up to 90 degrees because he didn't want his muscles to cool down," said Dabney. "You'd be like 'Wow, this is nuts.' But it separated him from everyone. He didn't just want it. He wanted it."

Bryant returned to ABCD for another summer and, as promised, was named the camp's MVP after averaging 21 points and 7 rebounds. This was perhaps the greatest collection of talent in ABCD history— not merely Bryant but also Thomas, Jermaine O'Neal of Eau Claire High (South Carolina), and Lester Earl of Glen Oaks (Louisiana). In a moment that, two decades later, Vaccaro still found uproarious, in one game Kobe soared toward the basket and slammed powerfully over an overwhelmed opponent. As the ball rattled through the rim, Bryant fell to his feet, smiled, and yelled at Vaccaro, "Was that better than Stephon's?"

"No," Vaccaro replied, "but it was damn good."

If Bryant's confidence was high off of his ABCD showing, a couple of closer-to-home experiences took it to another level. Even though he was but a high schooler, Bryant spent plenty of time playing pickup inside Temple University's Pearson Hall gymnasium. These weren't run-of-the-mill battles against Joe Frat Boy. No, his opponents included many of the Owls stars, including future NBA players Rick Brunson, Aaron McKie, and Eddie Jones. "God, he was so polished for a high school kid," recalled Jones. "Flat-out talented. Most impressive, he wasn't scared. We were All-Americans, big names in college basketball. And Kobe just brought it right at us. You knew this kid was NBA-bound. There was zero question."

Bryant returned to ABCD for another summer and, as promised, was named the camp's MVP after averaging 21 points and 7 rebounds. This was perhaps the greatest collection of talent in ABCD history— not merely Bryant but also Thomas, Jermaine O'Neal of Eau Claire High (South Carolina), and Lester Earl of Glen Oaks (Louisiana). In a moment that, two decades later, Vaccaro still found uproarious, in one game Kobe soared toward the basket and slammed powerfully over an overwhelmed opponent. As the ball rattled through the rim, Bryant fell to his feet, smiled, and yelled at Vaccaro, "Was that better than Stephon's?"

"No," Vaccaro replied, "but it was damn good."

If Bryant's confidence was high off of his ABCD showing, a couple of closer-to-home experiences took it to another level. Even though he was but a high schooler, Bryant spent plenty of time playing pickup inside Temple University's Pearson Hall gymnasium. These weren't run-of-the-mill battles against Joe Frat Boy. No, his opponents included many of the Owls stars, including future NBA players Rick Brunson, Aaron McKie, and Eddie Jones. "God, he was so polished for a high school kid," recalled Jones. "Flat-out talented. Most impressive, he wasn't scared. We were All-Americans, big names in college basketball. And Kobe just brought it right at us. You knew this kid was NBA-bound. There was zero question."

L-R: John Lucas, Jerry Stackhouse, Rick Mahorn

Around this time, the Philadelphia 76ers were holding off-season workouts on the campus of St. Joseph's. Because he was a big local name and bodies were needed (and because Tarvia Lucas, the daughter of 76ers coach John Lucas, attended Lower Merion), Bryant, along with Dabney, was allowed to play. These were the 18-64 Sixers of Shawn Bradley and Sean Higgins; of Elmer Bennett and Greg Graham. But they were still an NBA team, and Kobe Bryant was still a soon-to-be high school senior.

What transpired is the stuff of myth. In large part because much of it is myth. According to the eternally repeated story of 10 million witnesses (there were no more than 30 people in the gym), Bryant lit up Jerry Stackhouse, Philadelphia's fantastic young shooting guard. He took Stackhouse left, he took Stackhouse right, he dunked over Stackhouse while eating a ham sandwich and humming Peter Cetera's entire musical catalog.

Truth be told, Bryant played extremely well against Stackhouse, as well as solid NBAers like Vernon Maxwell, Richard Dumas, and Sharone Wright. He wasn't the most polished player on the court, or even the 10th most polished on the court. He was undisciplined, sloppy, erratic. He took shots one shouldn't take and committed turnovers that, were this a regular game, would land him on the bench. But he was absolutely fearless— and that stuck. Plus, while he didn't destroy Stackhouse, he did get under his skin. "Stack had a very short fuse," said Dabney. "He didn't take well to a 17-year-old bringing it to him." John Nash, general manager of the Washington Bullets, caught up with Lucas.

"How's Stack doing in your workouts?" Nash asked.

"Fine," Lucas said, "but he's the second-best two guard in the gym."

Nash made a mental list of the Sixers' shooting guards. It wasn't a particularly impressive collection. "John," he finally said, "who's the best two guard?"

"Kobe," Lucas replied.

Whoa.

Shaun Powell, a Newsday reporter who covered a lot of NBA, was walking through the New Jersey Nets' locker room one day when he was stopped by Rick Mahorn, journeyman power forward. "You know who you need to write about?" Mahorn said. "Jellybean's kid."

"Jellybean's kid?" Powell replied.

"Yeah," said Mahorn. "His name is Kobe. And in the summer when we all played pickup ball, he ran with us. And he wasn't the last one picked . . ."

What transpired is the stuff of myth. In large part because much of it is myth. According to the eternally repeated story of 10 million witnesses (there were no more than 30 people in the gym), Bryant lit up Jerry Stackhouse, Philadelphia's fantastic young shooting guard. He took Stackhouse left, he took Stackhouse right, he dunked over Stackhouse while eating a ham sandwich and humming Peter Cetera's entire musical catalog.

Truth be told, Bryant played extremely well against Stackhouse, as well as solid NBAers like Vernon Maxwell, Richard Dumas, and Sharone Wright. He wasn't the most polished player on the court, or even the 10th most polished on the court. He was undisciplined, sloppy, erratic. He took shots one shouldn't take and committed turnovers that, were this a regular game, would land him on the bench. But he was absolutely fearless— and that stuck. Plus, while he didn't destroy Stackhouse, he did get under his skin. "Stack had a very short fuse," said Dabney. "He didn't take well to a 17-year-old bringing it to him." John Nash, general manager of the Washington Bullets, caught up with Lucas.

"How's Stack doing in your workouts?" Nash asked.

"Fine," Lucas said, "but he's the second-best two guard in the gym."

Nash made a mental list of the Sixers' shooting guards. It wasn't a particularly impressive collection. "John," he finally said, "who's the best two guard?"

"Kobe," Lucas replied.

Whoa.

Shaun Powell, a Newsday reporter who covered a lot of NBA, was walking through the New Jersey Nets' locker room one day when he was stopped by Rick Mahorn, journeyman power forward. "You know who you need to write about?" Mahorn said. "Jellybean's kid."

"Jellybean's kid?" Powell replied.

"Yeah," said Mahorn. "His name is Kobe. And in the summer when we all played pickup ball, he ran with us. And he wasn't the last one picked . . ."

Continued below...

Kobe Turns Pro - 2

Three Ring Circus: Kobe, Shaq, Phil and the Crazy Years of the Lakers Dynasty

Jeff Pearlman (2020)

Jeff Pearlman (2020)

Around this time, Bryant began working daily with Joe Carbone, a personal trainer and retired professional weight lifter hired by the family to transform the kid from sapling to oak. The goal was to build someone described as "wiry" into a machine capable of enduring an 82-game season against large men. Before long, Bryant was a weight room regular, benching, squatting, curling. "We put about 20 pounds on him," Carbone said. "He's not a heavy gainer, so the weight came on as he got stronger."

By the time he returned to Lower Merion for his senior year of high school, Bryant knew he would not be attending college. "He told me that summer," said Dabney. "I'm going to the NBA next year." If Bryant knew, it was something of a secret to those hoping otherwise. The college recruiting letters arrived by the boatload— from Duke and North Carolina, from UCLA and USC, from Delaware and Drexel and Villanova and Temple. This was the fall of 1995, and at the time Joe Bryant was in his second year as an assistant at nearby LaSalle University, his alma mater. He had been hired in 1993 by Speedy Morris, the head coach, and while the official reasoning was that the program needed a replacement for the recently departed Randy Monroe, the reality was different. "Did I think it'd help us get Kobe?" Morris said decades later. "Yes. Of course. Joe was not a good assistant coach. He didn't work hard, he didn't actually know that much. Nice guy. But he was there so we'd get his son."

Kobe Bryant basked in the attention, took a handful of campus visits, pretended he was genuinely torn over what to do next. He liked to show off all the recruiting letters he received, and proudly stiffed Kentucky coach Rick Pitino, failing to show up for a scheduled visit to campus. He acted as if college were a legitimate option. Only it really wasn't. Because he had never signed with an agent, or accepted so much as a dime from a sneaker company, he remained eligible should he change his mind. But he wasn't changing his mind. The recruiting letters ultimately found themselves at rest alongside half-eaten burgers and empty yogurt containers in the Bryant family trash bins.

That June he had competed in the War in the Woods, an outdoor tournament held in Penns Grove, New Jersey. As Kobe lit up the court, his father watched alongside Gary Charles, veteran AAU coach and Sonny Vaccaro's confidant. With each Kobe three-pointer, Joe turned to Charles to say, "See that?" With each dunk, "Amazing, right?" When the game ended, Joe went serious. "Gary," he said, "I think my kid wants to come right out from high school. But we, as a family, would be worried because there are no guarantees."

Charles grinned. "What if I can help you get a guarantee?" he said.

Joe Bryant was confused.

"What," Charles said, "if I can help Kobe get a shoe deal?"

"Wait, you can do that?" Bryant replied.

"You know," Charles said, "I believe I can."

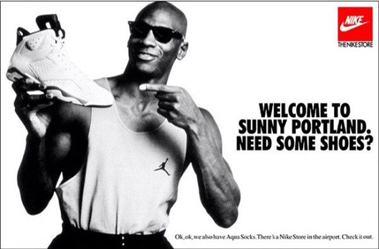

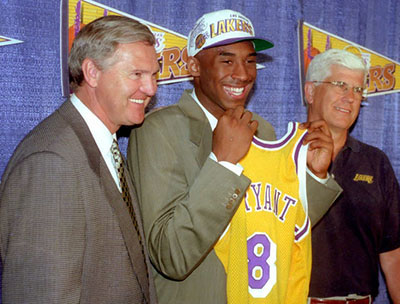

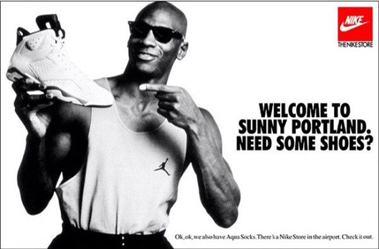

L-R: Kobe Bryant as high school senior, Michael Jordan Nike ad

That evening, Charles placed a call to Vaccaro.

"Sonny," he said, "Kobe Bryant can be the kid."

By the kid, he meant The One. Ever since joining Adidas in the early 1990s, Vaccaro had been seeking out the next Michael Jordan, jock marketing goliath. At the time, the shoe company was known for being dull and unimaginative and a pimple on Nike's back. Bryant's ABCD showings had opened Vaccaro's eyes, and there was a lot to like. Bryant was mature, Bryant was savvy, Bryant was handsome, Bryant could flat-out play, Bryant had NBA blood. "And the name— 'Kobe Bryant,'" Vaccaro said. "There's something about it. 'Kobe Bryant from Italy'— it's intriguing, it's a little mysterious."

Vaccaro loved what he was hearing. He reached out to Joe Bryant to make sure there was legitimate interest. Then he kicked back and watched Kobe piece together one of the best seasons in local high school basketball history, leading Lower Merion to its first state championship since 1943. He concluded his high school career as southeastern Pennsylvania's all-time leading scorer, with 2,883 points, and was named the Naismith High School Player of the Year, Gatorade Men's National Basketball Player of the Year, and a McDonald's All-American. "The most amazing thing was he never lost a drill," said Jeremy Treatman, an assistant coach with the Aces. "Four years, and Kobe never lost a game of one-on-one, a scrimmage, a sprint. He just didn't allow losing." By early in the season, word had gotten out that Bryant was thinking NBA, and the league's scouts (the ones who took him seriously— many did not) began to dot the Lower Merion bleachers during home games. Pete Babcock, general manager of the Atlanta Hawks, flew in and saw a kid "do whatever he wanted to without anyone knowing how to stop him." Larry Harris, a Milwaukee Bucks scout, came three times, often wondering if what he was witnessing was, in fact, real. "He wore number 33, and that immediately made me think of Scottie Pippen," Harris said. "He had this Pippen-like length, and also this comfort with his own athleticism. Once the game started, there was no messing around, no settling for jumpers. It was business. That jumped out to me."

Vaccaro was now more determined than ever to make Bryant the face of Adidas. Midway through the high school season, he convinced the company to spend $ 75,000 to move him from Southern California to New York City in order to be closer to the high school supernova. He never attended Lower Merion games, for fear that Nike or another rival apparel company would learn of his plans, but had Charles show up as his go-between. The two sides talked about fame and glory and talent. But mostly they talked about sneakers. The Bryant family wanted a financial guarantee, and Vaccaro and Adidas were willing to offer one. They would pay Kobe Bryant $48 million, provide another $150,000 to Joe Bryant, and make Kobe the face of Adidas. The sell, in a sense, was Michael Jordan. Bryant was told he would be the new Jordan— beginning with a signature shoe and a glitzy marketing campaign based around the concept "Feet You Wear." It played to both his ego and his love of basketball history. College? Who needed college. Kobe Bryant had decided to take his talents to the NBA.

When one is aligned with a sneaker company, and when said sneaker company is paying one millions of dollars to promote the brand, things can get complicated. In the aftermath of Kobe Bryant's going-to-the-NBA announcement, a slew of franchises asked him to come to their facilities for workouts. This is how things work in professional basketball, and a young player would have to be either dumb, uninformed, or supremely confident (nay, arrogant) to turn down an invitation. Especially a young player with no Division I college experience.

Kobe Bryant turned down plenty of invitations. For the not-yet-18-year-old guard, this was never about preferring the sun over the ski, or Pacific time over Eastern time. Nope, this was about selling sneakers. As soon as Vaccaro convinced Adidas to spend millions on the kid, it brought forth an immediate two-way loyalty. When Bryant (and his parents) went about finding an agent, he selected Arn Tellem, the Los Angeles–based power broker whose closest friends included Vaccaro and Lakers vice president Jerry West. Tellem, like Vaccaro, knew the importance of a big city for Kobe the basketball player and Kobe the apparel salesman. The Toronto Raptors, talentless, anonymous, and gifted with the second overall pick in the 1996 draft, asked Bryant to come for a visit. No. The Vancouver Grizzlies, talentless, anonymous, and gifted with the third overall pick in the 1996 draft, asked Bryant to come for a visit. No. The Milwaukee Bucks, talentless, anonymous, and gifted with the fourth overall pick in the 1996 draft, asked Bryant to come for a visit. No. One after another, Bryant offered a sincere thanks-but-no-thanks to the majority of organizations that wanted to see him in a controlled setting. On June 24, he was scheduled to fly to Charlotte and perform for the Hornets, owners of the 13th overall selection. That morning, without warning, he canceled. A day later, he did the same to the Sacramento Kings. No heads-up. No advance notice.

Early Kobe Bryant Adidas Ad

Bryant worried about his reputation, and whether organizations would hold it against him come draft day. Tellem promised all would work itself out. "We have to be selective," he told him. Indeed, the teams that had seen Bryant in person were blown away. Barry Hecker, the Los Angeles Clippers' assistant coach, wanted nothing to do with a high school kid when his bosses said Bryant would be arriving for a workout. "I was very skeptical," Hecker said. "I didn't think our organization would be a good spot for someone that young, and I also assumed he wouldn't be ready for a man's game. Well, that was misguided." Standing alongside Bill Fitch, the head coach, and assistant Jim Brewer, Hecker steeled himself to see the worst. Then— WHOOSH! Bryant was instructed to do the old Mikan Drill, which involves a rapid-fire series of close-to-the-basket hook shots. But instead of hooks, Bryant dunked. Bam! Bam! Bam! Bam! "Ten times in a row— left, right, left, right," said Hecker. "Jesus Christ."

Hecker was impressed. As were the New Jersey Nets, owners of the eighth overall pick. Officially, they had Bryant come to the team facility for three different workouts. Unofficially, that number was actually four. Or, ahem, maybe five. "Which is probably against NBA rules," said Bobby Marks, the Nets' basketball operations assistant. "But that's okay." Marks was in charge of scheduling Bryant's arrival via train or plane. He would pick him up from the station or airport, drive him to the facility, arrange for a series of challenges. At the time, the Nets were simultaneously awful and young, and it wasn't hard to rope in a green player or two to square off against a prospect. So one day Marks requested that guard Khalid Reeves and forward Ed O'Bannon come in early and rough up the high schooler. Kobe Bryant waxed them. "It was always some sort of two-on-two or three-on-three, and Kobe had his way," recalled Marks. "He was the best player on the court every single time, and it was against established NBA players." Word quickly spread that New Jersey was a likely destination for Bryant. That's why Jerry West considered Bryant worth little thought. The Lakers were picking 24th overall. The kid would be long gone. Plus, he was a high schooler, and Los Angeles was looking for help-now talent. "I didn't know much about him," West later said. "We weren't focused on getting Kobe Bryant."

Tellem, though, loved the idea of Los Angeles— the big market, the historic franchise. He called West and asked that the Lakers bring his client in for a workout. So they did. Bryant was in town for a commercial shoot, and he arrived at the Inglewood YMCA at the same time as Dontae' Jones, the Mississippi State forward who had recently led the Bulldogs to the Final Four. Over the next 45 minutes, Bryant reduced the 6-foot-8 Jones to a bowl of melted ice cream. With Larry Drew, a Lakers assistant coach, monitoring the workout, Bryant and Jones played a series of one-on-one games that left the college senior gasping for breath. "You don't realize," Jones said later, "a 17-year-old could do all the things he was even attempting to do." In his three and a half decades in professional basketball, West had seen everything. Elgin Baylor, Kareem, Magic, Bird, Jordan, Yinka Dare. This, though, was different. "Oh my God," West recalled. "You have to be kidding me. No disrespect to anyone, but as soon as I saw him it was clear this was a complete no-brainer. I swear to God, I would have taken him with the No. 1 pick in the draft over Allen Iverson. He was that good."

A couple of days later, the Lakers asked Bryant to attend one final workout. He was to play one-on-one against Michael Cooper, the former Laker star now working as an assistant coach with the club. Though five years retired, the 40-year-old Cooper looked a lot like the 30-year-old Cooper. He was sinewy, muscled, very much in shape. West asked his former player to give Kobe Bryant a beating. "Make him work," West said. Cooper nodded. "No problem." For 30 minutes, Bryant plowed through Cooper just as he had plowed through Jones. Slicing left, twirling right, dunking, gliding. West cut the one-on-one session short and turned to John Black and Raymond Ridder, two of the team's media relations heads. "Okay, I've seen enough," he said. "Let's go. He's better than anyone we have on our team right now."

He concluded: "Best workout I've ever seen."

Later that day, West reached out to Tellem. "Kobe Bryant," he told him, "just played like I'd never seen a kid play before. Obviously we'd love to have him as a Laker. Not sure how that happens, but . . ."

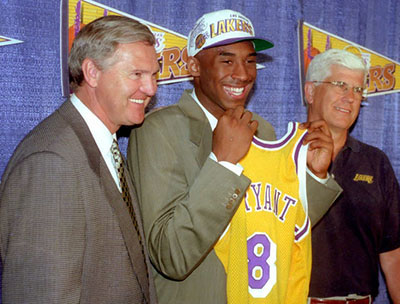

The rest is history of course. West arranged a trade with the Hornets. Charlotte would take Bryant at #3, then swap him to the Lakers for Vlade Divac. Amazingly, the first 12 teams passed on Kobe and the deal came to fruition.

L-R: Jerry West, Kobe Bryant, and Lakers Coach Del Harris on Draft Night

By the time he returned to Lower Merion for his senior year of high school, Bryant knew he would not be attending college. "He told me that summer," said Dabney. "I'm going to the NBA next year." If Bryant knew, it was something of a secret to those hoping otherwise. The college recruiting letters arrived by the boatload— from Duke and North Carolina, from UCLA and USC, from Delaware and Drexel and Villanova and Temple. This was the fall of 1995, and at the time Joe Bryant was in his second year as an assistant at nearby LaSalle University, his alma mater. He had been hired in 1993 by Speedy Morris, the head coach, and while the official reasoning was that the program needed a replacement for the recently departed Randy Monroe, the reality was different. "Did I think it'd help us get Kobe?" Morris said decades later. "Yes. Of course. Joe was not a good assistant coach. He didn't work hard, he didn't actually know that much. Nice guy. But he was there so we'd get his son."

Kobe Bryant basked in the attention, took a handful of campus visits, pretended he was genuinely torn over what to do next. He liked to show off all the recruiting letters he received, and proudly stiffed Kentucky coach Rick Pitino, failing to show up for a scheduled visit to campus. He acted as if college were a legitimate option. Only it really wasn't. Because he had never signed with an agent, or accepted so much as a dime from a sneaker company, he remained eligible should he change his mind. But he wasn't changing his mind. The recruiting letters ultimately found themselves at rest alongside half-eaten burgers and empty yogurt containers in the Bryant family trash bins.

That June he had competed in the War in the Woods, an outdoor tournament held in Penns Grove, New Jersey. As Kobe lit up the court, his father watched alongside Gary Charles, veteran AAU coach and Sonny Vaccaro's confidant. With each Kobe three-pointer, Joe turned to Charles to say, "See that?" With each dunk, "Amazing, right?" When the game ended, Joe went serious. "Gary," he said, "I think my kid wants to come right out from high school. But we, as a family, would be worried because there are no guarantees."

Charles grinned. "What if I can help you get a guarantee?" he said.

Joe Bryant was confused.

"What," Charles said, "if I can help Kobe get a shoe deal?"

"Wait, you can do that?" Bryant replied.

"You know," Charles said, "I believe I can."

L-R: Kobe Bryant as high school senior, Michael Jordan Nike ad

"Sonny," he said, "Kobe Bryant can be the kid."

By the kid, he meant The One. Ever since joining Adidas in the early 1990s, Vaccaro had been seeking out the next Michael Jordan, jock marketing goliath. At the time, the shoe company was known for being dull and unimaginative and a pimple on Nike's back. Bryant's ABCD showings had opened Vaccaro's eyes, and there was a lot to like. Bryant was mature, Bryant was savvy, Bryant was handsome, Bryant could flat-out play, Bryant had NBA blood. "And the name— 'Kobe Bryant,'" Vaccaro said. "There's something about it. 'Kobe Bryant from Italy'— it's intriguing, it's a little mysterious."

Vaccaro loved what he was hearing. He reached out to Joe Bryant to make sure there was legitimate interest. Then he kicked back and watched Kobe piece together one of the best seasons in local high school basketball history, leading Lower Merion to its first state championship since 1943. He concluded his high school career as southeastern Pennsylvania's all-time leading scorer, with 2,883 points, and was named the Naismith High School Player of the Year, Gatorade Men's National Basketball Player of the Year, and a McDonald's All-American. "The most amazing thing was he never lost a drill," said Jeremy Treatman, an assistant coach with the Aces. "Four years, and Kobe never lost a game of one-on-one, a scrimmage, a sprint. He just didn't allow losing." By early in the season, word had gotten out that Bryant was thinking NBA, and the league's scouts (the ones who took him seriously— many did not) began to dot the Lower Merion bleachers during home games. Pete Babcock, general manager of the Atlanta Hawks, flew in and saw a kid "do whatever he wanted to without anyone knowing how to stop him." Larry Harris, a Milwaukee Bucks scout, came three times, often wondering if what he was witnessing was, in fact, real. "He wore number 33, and that immediately made me think of Scottie Pippen," Harris said. "He had this Pippen-like length, and also this comfort with his own athleticism. Once the game started, there was no messing around, no settling for jumpers. It was business. That jumped out to me."

Vaccaro was now more determined than ever to make Bryant the face of Adidas. Midway through the high school season, he convinced the company to spend $ 75,000 to move him from Southern California to New York City in order to be closer to the high school supernova. He never attended Lower Merion games, for fear that Nike or another rival apparel company would learn of his plans, but had Charles show up as his go-between. The two sides talked about fame and glory and talent. But mostly they talked about sneakers. The Bryant family wanted a financial guarantee, and Vaccaro and Adidas were willing to offer one. They would pay Kobe Bryant $48 million, provide another $150,000 to Joe Bryant, and make Kobe the face of Adidas. The sell, in a sense, was Michael Jordan. Bryant was told he would be the new Jordan— beginning with a signature shoe and a glitzy marketing campaign based around the concept "Feet You Wear." It played to both his ego and his love of basketball history. College? Who needed college. Kobe Bryant had decided to take his talents to the NBA.

When one is aligned with a sneaker company, and when said sneaker company is paying one millions of dollars to promote the brand, things can get complicated. In the aftermath of Kobe Bryant's going-to-the-NBA announcement, a slew of franchises asked him to come to their facilities for workouts. This is how things work in professional basketball, and a young player would have to be either dumb, uninformed, or supremely confident (nay, arrogant) to turn down an invitation. Especially a young player with no Division I college experience.

Kobe Bryant turned down plenty of invitations. For the not-yet-18-year-old guard, this was never about preferring the sun over the ski, or Pacific time over Eastern time. Nope, this was about selling sneakers. As soon as Vaccaro convinced Adidas to spend millions on the kid, it brought forth an immediate two-way loyalty. When Bryant (and his parents) went about finding an agent, he selected Arn Tellem, the Los Angeles–based power broker whose closest friends included Vaccaro and Lakers vice president Jerry West. Tellem, like Vaccaro, knew the importance of a big city for Kobe the basketball player and Kobe the apparel salesman. The Toronto Raptors, talentless, anonymous, and gifted with the second overall pick in the 1996 draft, asked Bryant to come for a visit. No. The Vancouver Grizzlies, talentless, anonymous, and gifted with the third overall pick in the 1996 draft, asked Bryant to come for a visit. No. The Milwaukee Bucks, talentless, anonymous, and gifted with the fourth overall pick in the 1996 draft, asked Bryant to come for a visit. No. One after another, Bryant offered a sincere thanks-but-no-thanks to the majority of organizations that wanted to see him in a controlled setting. On June 24, he was scheduled to fly to Charlotte and perform for the Hornets, owners of the 13th overall selection. That morning, without warning, he canceled. A day later, he did the same to the Sacramento Kings. No heads-up. No advance notice.

Early Kobe Bryant Adidas Ad

Hecker was impressed. As were the New Jersey Nets, owners of the eighth overall pick. Officially, they had Bryant come to the team facility for three different workouts. Unofficially, that number was actually four. Or, ahem, maybe five. "Which is probably against NBA rules," said Bobby Marks, the Nets' basketball operations assistant. "But that's okay." Marks was in charge of scheduling Bryant's arrival via train or plane. He would pick him up from the station or airport, drive him to the facility, arrange for a series of challenges. At the time, the Nets were simultaneously awful and young, and it wasn't hard to rope in a green player or two to square off against a prospect. So one day Marks requested that guard Khalid Reeves and forward Ed O'Bannon come in early and rough up the high schooler. Kobe Bryant waxed them. "It was always some sort of two-on-two or three-on-three, and Kobe had his way," recalled Marks. "He was the best player on the court every single time, and it was against established NBA players." Word quickly spread that New Jersey was a likely destination for Bryant. That's why Jerry West considered Bryant worth little thought. The Lakers were picking 24th overall. The kid would be long gone. Plus, he was a high schooler, and Los Angeles was looking for help-now talent. "I didn't know much about him," West later said. "We weren't focused on getting Kobe Bryant."

Tellem, though, loved the idea of Los Angeles— the big market, the historic franchise. He called West and asked that the Lakers bring his client in for a workout. So they did. Bryant was in town for a commercial shoot, and he arrived at the Inglewood YMCA at the same time as Dontae' Jones, the Mississippi State forward who had recently led the Bulldogs to the Final Four. Over the next 45 minutes, Bryant reduced the 6-foot-8 Jones to a bowl of melted ice cream. With Larry Drew, a Lakers assistant coach, monitoring the workout, Bryant and Jones played a series of one-on-one games that left the college senior gasping for breath. "You don't realize," Jones said later, "a 17-year-old could do all the things he was even attempting to do." In his three and a half decades in professional basketball, West had seen everything. Elgin Baylor, Kareem, Magic, Bird, Jordan, Yinka Dare. This, though, was different. "Oh my God," West recalled. "You have to be kidding me. No disrespect to anyone, but as soon as I saw him it was clear this was a complete no-brainer. I swear to God, I would have taken him with the No. 1 pick in the draft over Allen Iverson. He was that good."

A couple of days later, the Lakers asked Bryant to attend one final workout. He was to play one-on-one against Michael Cooper, the former Laker star now working as an assistant coach with the club. Though five years retired, the 40-year-old Cooper looked a lot like the 30-year-old Cooper. He was sinewy, muscled, very much in shape. West asked his former player to give Kobe Bryant a beating. "Make him work," West said. Cooper nodded. "No problem." For 30 minutes, Bryant plowed through Cooper just as he had plowed through Jones. Slicing left, twirling right, dunking, gliding. West cut the one-on-one session short and turned to John Black and Raymond Ridder, two of the team's media relations heads. "Okay, I've seen enough," he said. "Let's go. He's better than anyone we have on our team right now."

He concluded: "Best workout I've ever seen."

Later that day, West reached out to Tellem. "Kobe Bryant," he told him, "just played like I'd never seen a kid play before. Obviously we'd love to have him as a Laker. Not sure how that happens, but . . ."

The rest is history of course. West arranged a trade with the Hornets. Charlotte would take Bryant at #3, then swap him to the Lakers for Vlade Divac. Amazingly, the first 12 teams passed on Kobe and the deal came to fruition.

L-R: Jerry West, Kobe Bryant, and Lakers Coach Del Harris on Draft Night

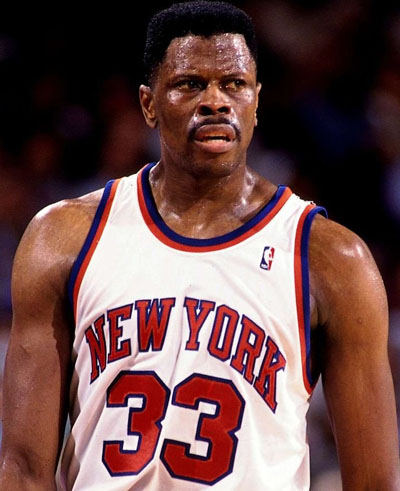

Demise of the Post Game

"The Lost Art of the NBA,"

Chris Ballard, Sports Illustrated (February 2023)

For generations, giants ruled from the blocks. Today? Post play is an afterthought, lost to pace and space. But there remain a few who preach the forgotten craft - and seek its return.