|

James A. Naismith was a physical education instructor at theInternational Young Men’s Christian Association Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1891. Chief among his duties was to lead classes through daily indoor exercise routines. Those routines included marching, calisthenics, and games like leapfrog. Many students didn't want to do these boring and childish activities, however. They were used to competitive sports like baseball and football – activities that challenged them physically and mentally and were exciting, too. They found jumping jacks and somersaults to be poor substitutes and demanded a new indoor activity. |

Naismith tried to figure out why the sports hadn't worked indoors. Football had failed, he decided, because players were hurt when they were tackled while running with the ball. If players weren't allowed to run with the ball, then they wouldn't get hurt.

So how was a player to move the ball if he couldn't run with it? His indoor soccer experiment had proved that kicking the ball wouldn't work. Arming players with sticks like those used in lacrosse or hockey struck him as too dangerous.

What if the ball was passed from teammate to teammate? Tackling would be illegal, but a player could bat the ball away in midflight and capture it for himself. Injuries would be much less likely to occur if the defense focused on the ball and not the player.

Next Naismith turned his attention to how points should be scored. Withthe exception of baseball, most sports featured two goals set up at opposite ends of a playing field. They all used the same general scoring method: power an object past a goalkeeper with as much speed and force as possible to earn a point.

Naismith liked the idea of opposing goals, but in his opinion – and recent experience – power, force, and speed were too dangerous for confined, indoor play. So instead of players hurling the ball laterally toward a goal protected by a player at ground level, he decided they would toss it vertically toward an untended goal mounted up high. Skill and accuracy, not power, would earn points, and no one player would be responsible for preventing goals.

From these starting points, Naismith came up with thirteen general rules for his new game. He posted those rules on the YMCA's gymnasium door in late December of 1891. He nailed a peach basket – the first hoops – at each end of a railing that circled the gym floor. The railing was ten feet above the floor, and to this day, that is the height at which basketball hoops are hung.

Geneva College (Beaver Falls PA) basketball team 1891

The Big O: My Life, My Times, My Game, Oscar Robertson (2003)

It is 1956 and Oscar Robertson has just led Crispus Attucks High School in Indianapolis to its second straight state championship.

I didn't say anything to the press, but certainly read his comments. Before the first game, which was in Indiana, our team had steaks at a restaurant called the 500 Club and discussed strategy. ... When [coach] asked who wanted to guard Coleman, about half the team raised their hands. Angus looked at all of them, then at me. "Oscar, you've got him."

Kentucky continued the tradition of teams getting off to comically fast starts against me. Their squad came out onto our home court and scored the first seven points. We regrouped enough to tie the score at 10, then took a 12-10 lead. Throughout, I worked pretty hard on defense, crowding Coleman and denying him the ball. He ended with three points in the first half, and we stretched our lead. During the second half, whenever Kentucky threatened, I either drove and hit someone for an assist, nailed a jump shot, or finished a play myself. We took the first game going away, 92-78. I ended up with thirty-four points, breaking the single-game scoring record by six. Coleman finished with seventeen, most of them coming during the fourth quarter.

The second game was more of the same, only this time it was played in Louisville, Kentucky. We scored thirty points in the third quarter and blew their doors off, 102-77. This time, Coleman ended up with all of four points, from one of nine shooting. I broke my new record, scoring my fortieth and forty-first points, when our coach reinserted me into the game with seconds left, for a shot at the buzzer.

John Taylor (2005)

Then, in a game against Minneapolis at the end of his third season, Stokes had his feet kicked out from under him, fell to the floor, and hit his head on the hardwood. It briefly knocked him out, but he regained consciousness within a minute, and seemed none the worse for the fall. Three days later, however, in a playoff game in Detroit, he inexplicably felt so weak that he seemed ill, and he played badly. ... as soon as the plane took off on the flight home from Detroit, Stokes began sweating heavily and moaning incoherently, and then he passed out. The captain radioed ahead for an ambulance, which met the team at the Cincinnati airport.

Apparently, the concussion three days earlier in the game against Minneapolis had caused Stokes's head to swell, and then the changing air pressure in the cabin as the airplane took off stimulated an attack of encephalitis. Stokes was in a coma by the time the plane touched down. Early the following morning, surgeons operated on his brain but were unable to reverse the effects of the attack. Afterward, Stokes regained consciousness, but the stroke had seriously damaged his motor nerves, and for the rest of his life he would be virtually unable to move or talk.

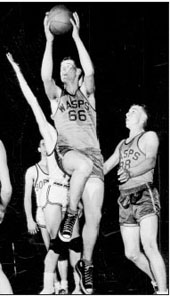

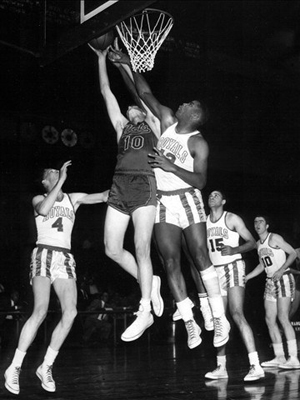

Stokes blocking a shot; Twyman is #10.

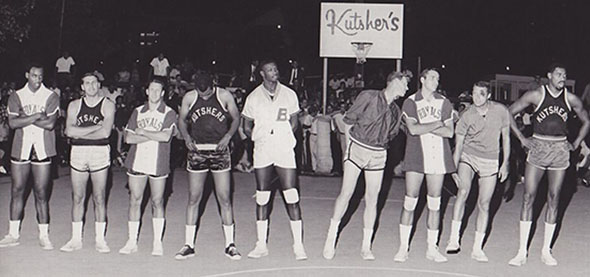

NBA players gathered for Maurice Stokes Benefit Game

Wilt Chamberlain, Maurice Stokes, Jack Twyman

Who Played, Coached, and Built Pro Basketball, Terry Pluto (1992)

Players, coaches, and officials from the 1950s reminisce about playing in Syracuse.

Dolph Schayes

Al McGuire |

Syracuse star Dolph Schayes: Syracuse had a wonderful small-town feel to it. When you played for the Nats, the whole town embraced you, like Green Bay does with the Packers or Portland with the Blazers. We thought of ourselves as the underdog, the little guy taking on the big city. Our arena had only 6,400 seats and the fans were righton top of you.

Referee Norm Drucker: You'd go to Syracuse and the fans knew you were there ... You'd be having bacon and eggs in the hotel coffee shop and some guy would stop by and say, "You're Drucker, right? You screwed us last time, don't do it again." Then you'd step on the court and look at the Syracuse bench and there was Danny Biasone. Young officials would point to him and say, "Who's that guy?" I'd say, "He owns the team." Then I could see a lump in the official's throat. He was thinking, "I better not mess up or this guy will be on the phone to my boss." Referee Sid Borgia: People tell me that [Danny] was good because he didn't say much on the bench. In that building, he didn't have to. Officials deserved combat pay for working in Syracuse. Those fans were so crazy and they never believed their team did anything wrong. Syracuse C Johnny Kerr: Another reason that Danny didn't have to say anything was that [coach] Al Cervi could work the crowd. When a call went against us, he'd turn his back to the court, face the fans, raise his hands to the heavens as if to say, "Why is God punishing us with these officials?" Then the crowd would take over and shower the court with popcorn boxes and orange juice cartons. Referee Earl Strom: Their public address announcer was the worst. I'd work a Syracuse-Philly game. I'm from Pottstown, Pennsylvania, which is not a suburb of Philadelphia. But in Syracuse, they'd introduce me as "Earl Strom from Philadelphia." Right away, the crowd is on my butt. ... Syracuse would commit their sixth foul of the period and the guy would say, "For Syracuse, that's six team fouls. Philadelphia has only one." Again, the house would come down on you. ... Referee John Vanak: Syracuse knew that it was tough to call fouls on them at home. They had guys like Al Bianchi, who just loved to flatten people. Al would knock a player on his ass and almost dare you to call a foul on him and take the heat from the crowd. Back then, there were no flagrant fouls. A guy could drive the lane, Al could hammer him, they would have to call an ambulance and it would still be only two shots. Syracuse G Al Bianchi: Against the good teams, our games were wars. Boston ... boy, we always had great fights with them. Vanak: There was a game where Jim Loscutoff grabbed Dolph Schayes by the throat with about two minutes left. They both fell down, and the next thing I knew fans were spilling out of the stands. We had a riot on our hands and it took a good half hour before we got the floor cleared and finished the game. Celtics G Frank Ramsey: The Syracuse fans were out of control. They'd throw cups full of Coke, programs, even batteries at you. That place was a hockey arena with sideboards. On the night of the big fight between Dolph and Loscutoff, the fans knocked over those hockey boards to get on the court and some of the fans were hurt when they ended up under the boards. It was like a stampede. Bianchi: There was a night when the Syracuse fans tried to storm the Boston dressing room. The players slammed the doors on a few hands, breaking their fingers. Another time, the Celtics were walking off the court after a game with a police escort. A fan dumped a beer on a Boston player. Vanak: The same kind of thing happened to Joe Gushue. He was leaving the court and a fan whacked him over the head with a rolled-up newspaper. Boston C Gene Conley: Oh, their fans ... you'd stand at the foul line and they'd throw candy bars at you. The guys on the bench got bombarded the most. Ramsey: There was a night the stuff being thrown at us was so bad that the officials told all of our subs to leave the bench and stay in the dressing room - for our own safety. The coach was out there alone. When Red Auerbach wanted to make a substitution, he had to stop the game. He'd send the player who was coming out into the dressing roo with the message of who Red wanted as a replacement. Conley: Poor Frank Ramsey. To get off the court, you had to walk through a tunnel that went through the stands. The fans were all over us and one of them grabbed Frank around the neck and was strangling him. I punched the guy or Frank would have choked. Drucker: They had a fan called the Strangler. He was about 5-foot-6, maybe 220 pounds with a tremendous chest and arms. He'd run up and down the sidelines during the game and stand next to a player, screaming, "You SOB, you stink." Strom: If I had to guess, it probably was the Strangler who grabbed Ramsey. That fan got his name when he picked up [official] Charley Eckman at halftime and had poor Charley hanging by the neck. Gene Conley hated that guy. One night, we were walking off the court and Gene saw the Strangler. Gene said, "When we get near that guy, duck." We got close. The Strangler reached down from the stands to grab me, I ducked and Conley drilled the guy, knocking his lights out with one punch. Drucker: The Strangler loved to run up to the Celtics' huddle and yell things. One night, I saw him there. Then I saw the huddle open, he disappeared inside and the huddle closed around him. When he came out, his mouth was bleeding. The Celtics worked him over. Borgia: Some of my scariest moments were in Syracuse. There was a game where Syracuse was down by three points with 15 seconds left. Dolph Schayes drove the lane, dipped his shoulder, ran smack into Sweetwater Clifton, and in the same motion, he threw in a shot. All the fans thought the basket was good and Schayes would be going to the foul line for a three-point play. John Nucatola was working the game with me, and he called a charge - no basket, New York ball. |

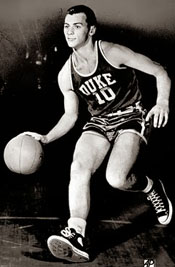

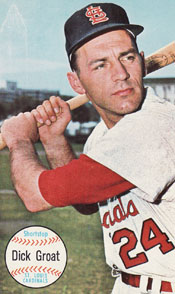

Duke had several basketball All-Americans before the 1950s, but Dick Groat was the school's first consensus All-American. The Pennsylvania native came to Duke to play baseball for Jack Coombs. He was a standout shortstop and led Duke to the 1952 College World Series. He went on to a 14-year major league career, which included winning the 1960 National League Most Valuable Player Award.

But Gerry Gerard and Howard Bradley were delighted to have Groat spend his winters on the basketball court. Barely six feet tall, Groat lacked exceptional quickness, strength, or leaping ability, but his intelligence, skills, and competitiveness made him a standout on the hardcourt. Groat's father would have preferred that his talented son stick to baseball. Remember that there was a lot more money in professional baseball than professional basketball in the 1950s. ... Several of Groat's individual efforts stand out. On January 6, 1951, hoops fans eagerly awaited the matchup between Groat and North Carolina State's Sammy Ranzino, each of whom was ranked among the nation's top 10 scorers. Groat won the individual duel 36 to 32, but State won the game 77-71 in overtime. Duke led 67-59 with six minutes left but could not score the rest of regulation. Helping temporarily shut down Groat was State defensive stopper Vic Bubas, the future Duke coach. Groat's 36 points established a school single-game scoring record. It lasted only three weeks. On January 29 Groat set a school record with 37 points in a 90-68 win over Davidson. Groat went 17-17 from the foul line in that game. Groat ended the season averaging 25.2 points per game, fourth in the nation. He was named National Player of the Year by UPI and by the Helms Athletic Foundation. If anything Groat was even better in 1952. He averaged 26 points per game, still the second-best mark in Duke history. In his final home game, on February 29, 1952, Groat scored a stunning 48 points to lead Duke to a 94-64 rout over North Carolina. He hit 19 field goals and 10 free throws and threw in a dozen assists for good measure. ... Duke finished the 1952 season ranked 12th in the AP poll, the first time Duke had ever ended a season nationally ranked. Groat was on all of the All-America teams and repeated as Southern Conference Player of the Year. His 26 points and 7.6 assists per game were both second in the nation. Later that spring Groat led the Duke baseball team to the College World Series. On May 1, 1952, Duke retired his number 12. He was the first Duke athlete to have his number retired. ... Fred Shabel was a sophomore reserve in 1952. His parents came down to Durham from New Jersey at the end of the 1952 season to see their first college basketball game. This was the game against North Carolina when Dick Groat scored 48 points. Coach Howard Bradley took Groat out with seconds left and replaced him with Shabel. Naturally, Groat received a prolonged standing ovation. After the game Shabel's parents were beaming. "Freddie, did you see how much they like you?" they told their son. "Everybody stood and cheered when you went into the game." Shabel never did tell his parents that the cheers were for Groat, not him. |

|

Loose Balls: The Short, Wild Life of the American Basketball Association as Told by the Players, Coaches, and Movers and Shakers Who Made It Happen, Terry Pluto (1990)

Cliff Hagan's locker room lectures were legendary. He'd get his players in the room and yell at them forever. The guys all talk about how Cliff burned their ears. To hear Cliff in the dressing room, you'd never believe it was the same guy you saw at the Baptist church ... He was so foul-mouthed that it was truly something to behold. I asked him about it and Cliff said, "I had eight coaches in the pros. I liked six of them and hated the other two. The only guys we won with were the guys I hated." Well, Cliff managed to get the players to hate him. They respected him as a player and a person, but they hated him as a coach. ...

The one incident that shook up some people was when we had a Kids' Day game on a Sunday afternoon at home. We were playing Minnesota with Mel Daniels and Les Hunter and they were one of the best teams in the league. We had our biggest crowd of the season, about 7,000, and most of them were kids. Early in the game, Hunter elbowed Cliff, they had words, and I figured Cliff told him don't try it again. Anyway, next time down the floor, Hunter elbowed Hagan again. Without a word, Hagan turned, faced Hunter and bam, bam, bam. It was an unbelievable right-left-right combination and Cliff just flattened Hunter.

The Dallas owners were just horrified. These were gentlemen and they came to a nice Sunday afternoon basketball game with their kids. The owners never heard a coach curse like Hagan and they never saw a fight like that on the court before. So the owners were unhappy about that, and they were unhappy because we lost our coach and our best player after 30 seconds and that was a good way to lose the game.

Mel Daniels

Cliff said, "Max, if I can't fight, I can't play."

I said, "If you fight and get thrown out, we have no coach and our best player is gone and then I have to come out of the stands and coach the team. (No one in the early ABA had assistants.) I don't want to coach. I hired you to coach."

I suggested that he coach the team, but not play. Maybe that would keep him out of trouble. So Cliff would dress for the games wearing his jersey and his warm-up pants, but no basketball shorts, just a jockstrap. That way he wouldn't be tempted to put himself in the game and that would keep him from getting in fights.

We went on a West Coast trip with the team and I was at a game in Anaheim against the Amigos. One of the players said to me, "Hey, Max, tonight Cliff has his shorts on." I started to worry.

But the game went on and on and Cliff didn't put himself in. With 40 seconds left, the score was tied and I saw Cliff rip off his warm-ups and put himself into the game. Cliff cut across the lane, caught a pass and made that great hook shot of his. Then one of the Anaheim players jumped on his back and rode Cliff right to the floor. Cliff stood up, looked at the guy and cold-cocked him.

I thought, "He's only been in the game for five seconds and he already punched somebody."

The amazing thing was that neither official saw it. Hagan stayed in the game and saved himself $2,500.

Hard Work: A Life on and off the Court, Roy Williams with Tim Crothers (2009)

Roy Williams is coaching at Kansas as this tale begins.

Mark Randall interrupted me. "Coach, can I say something?"

I nodded and Mark stood up and said, "We're too good to do what we just did today. If everybody in this room would do what this man says and everybody in this room would pull together, we can make a run and we can win the whole thing." Mark wasn't emotional at all. He said it very matter-of-factly.

We dominated the game inside, including 15 offensive rebounds in the first half, and we won 83-65. Then we played Arkansas, which was ranked No. 2 in the country. [Assistant Coach] Kevin Stallings prepared the scouting report for that game, and at our staff meeting, I said, "All right, give me a quick thought about Arkansas that I can share with the team."

"Kevin, don't say that. We can win the game."

"Coach, we have no chance."

"All right. I'm going to tell the team we're going to win the frickin' game."

"Coach, you know, that's worked in the past, but that isn't working this time."

"You just keep that to yourself."

And so we went to the team meeting that night, and I said, "Guys, we're in a great situation. We've already beaten the No. 3 team in the country, and now we're playing the No. 2 team, and we're going to win the game."

The players left and Kevin Stallings said, "You're crazy. We have no chance."

L-R: Mark Randall, Kevin Stallings, Bob Knight

I told the players, "This is what's going to happen. It's our ball to start the half. Let's get a great shot and knock it in and then we need one stop. Then let's get another great shot and get another stop. I'm only asking for two stops. Then let's come down and let's make sure we get a good look again and let's knock that in, and by then the lead falls from 12 to six and they'll probably call a timeout and then we'll see them bickering at each other."

We came out, moved the ball around and Terry Brown got a layup. Then we went down and got a stop. We came back down and Terry hit another layup. We went down and got that second stop, and then we came down and Mark Randall got fouled and made one of two free throws. We got a third stop and Alonzo Jamison hit a three-pointer to cut the lead down to four. Their coach, Nolan Richardson, called a timeout. As they were walking off the court, two of their guys, Roy Huery and Oliver Miller, were yapping at each other, and I grabbed one of our players and said, "See?"

We outscored Arkansas by 24 in the second half. It was a great win and we were going to the Final Four. The neatest part of the game came afterward. My son, Scott, sneaked down on the court, came running up to me, and said, "Dad, you've got to let me go to the Final Four."

I said, "The whole family will go to the Final Four."

The Last Great Game: Duke vs. Kentucky and the 2.1 Seconds

That Changed Basketball, Gene Wojciechowski (2012)

"They won a national championship," says Jimmy King. "They hadn't seen us yet. It's a new time. It's our time."

The Fab Five: King, Webber, Howard, Rose, Jackson

Rose, who was never on Duke's recruiting list, also played AAU ball with Grant and was friends with Hill and his family. "To be honest, I wanted a lot of the things that he had," says Rose.

The Michigan freshmen actually preferred the nickname "Five Times" rather than the Fab Five name they made famous. Whatever they were called, they had definitely caught the attention of the Blue Devils. The Duke players were aware of the hype, of their longer, baggier game shorts ..., of their growing popularity, and their swagger, which some of the Blue Devils thought was undeserved. After all, they had played only a few regular-season games against mediocre opposition.

"It was like the anti-culture from what our culture was," says Krzyzewski. "We looked at it as two different worlds ... and I think the public looked at it that way, too. Whether they liked them or liked us, it was a huge game."

Michigan students began lining up outside Crisler [Arena] in the cold and sleet as early as 5 a.m. on game day. It was only December 14, but there was almost a postseason feel to the matchup. The subplots (the Webber factor, Duke No. 1, the Fab Five hype, the cockiness of both teams, the preppy image of the Blue Devils, national television) all contributed to the intensity. ...

Duke led by 10 at halftime, 43-33. But Michigan reversed the numbers in the second half and forced the game into overtime, before the Blue Devils prevailed, 88-85.

Webber fouled out, but not before scoring 27 points and grabbing 12 rebounds. Laettner also fouled out, with 24 points and 8 rebounds. Michigan blocked 8 shots. Rose, Webber, and King accounted for 60 of the Wolverines' 85 points.

Says King: "It's early in the season and nobody really knew us. Then you've got the superpower coming in, and we're just going to bown down and show respect? Nuh, uh. That wasn't our mind-set."

"We should have beaten them by 20," says Davis.

Personal Fouls, Peter Golenbock (1989)

In his third recruiting year, after two so-so seasons, Valvano hit the jackpot. His first big score was in convincing Glenn Vickers, a six-foot-three-inch forward from Babylon, Long Island, rated the best player on the island, to come to Iona. Vickers had led Babylon High to two straight Long Island championships and was being courted by Southern Methodist University, the University of San Francisco, and several school in the Ivy League.

Valvano's tactic was to recruit Vickers' father, William, as hard as he did the son. Valvano promised William Vickers that his son would be the player around whom his entire program would be built. He also convinced the senior Vickers that it would be in the son's best interest to go to college near home. ...

Once Vickers signed up, Valvano was able to recruit a bruising young six-foot-ten center with a body of granite by the name of Jeff Ruland. Ruland, a senior at Sachem High School in Ronkonkoma, Long Island, averaged 29.5 points a game as a senior. Ruland later said that he respected Vickers' game so much that he wanted to play college ball with him.

As with Glenn Vickers' dad, Valvano played on the natural parental urges. He convinced Ruland's mom that if her boy went to Iona, close to home, he would be well taken care of, better than if he went to one of the faraway colleges that wanted him: Kentucky, Indiana, Notre Dame, and North Carolina.

Ruland, it turned out, was far the greater-impact player than Vickers. By his sophomore year, Ruland was rated by one professional scout as perhaps "the best college center in the country" and a "sure-fire first-round NBA pick."

After Iona lost to Holy Cross in a game marked by bickering among the Iona players, Ruland went home and told his mother, "We're dropping out."

Vickers and Ruland were planning to transfer together to one of the Ivy League schools that had recruited Vickers. It was a serious enough move that Valvano went before the rest of the squad and told them the two were leaving the team.

But that night he was saved by his parental admirers. Mrs. Ruland Swanson and William Vickers met with their sons at her workplace, Ernie's Tavern, named after her fourth husband, and at the meeting, Ruland's mom told her son, "I didn't raise no quitter. Now you two get back to Valvano, or I'll break your legs." Her loyalty may well have saved Valvano's career aspirations from being short-circuited.

With his two stars back, Valvano acted quickly to heal the schism on the team. With Iona playing an exhibition game against the Australian National Team, Valvano had Vickers and Ruland sit out the game - he told the rest of the squad they were hurt. After Iona was badly beaten, outshot and outrebounded, the other team membes, while still dismayed by the star treatment Ruland and Vickers were getting from the coaching staff - Ruland especially - at least had a fuller appreciation of what their teammates meant to the team's success.

"The rest of the squad realized we couldn't win without Rules and Vick," said Valvano. The end-of-year tally read seventeen victories and ten defeats, and though Iona didn't make any postseason tournaments, Valvano was fortunate to have his team intact for the 1977-78 season.

The following two seasons, the Gaels made the NCAA Tournament, losing in the 1st Round in '79 but moving to the 2nd round in '80. His success at Iona earned Valvano a promotion to North Carolina State, where he led the Wolfpack to a surprising NCAA Championship in 1983.

Harry Lancaster and Adolph Rupp

Rupp's sarcasm is legendary ... He told Milt Ticco, after the latter missed an easy shot that would have tied Ohio State at the end of regulation, that the Buckeyes ought to be awarding him a varsity letter. He told Dickie Parsons ..., "Did you know that I'm writing a book entitled What Not To Do in Basketball? The first two hundred pages are going to be about you." He told C.M. Newton and/or Gayle Rose: "You look like a Shetland Pony in a stud horse parade." He told John Crigler, "John Lloyd, a hundred and fifty years from now there will be no university, no fieldhouse. There will have been an atomic war, and it will all be destroyed. Underneath the rubble there will be a monument, on which is the inscription, 'Here lies John Criger, the most stupid basketball player ever at Kentucky, killed by Adolph Rupp.'" He told mountain-boy Ernest Sparkman during the 1944 NIT, "Sparkman, you see that center circle? I want you to go out there and shit. Then you can go back to Carr Creek and tell them at least you did something in Madison Square Garden."