Basketball, on the other hand, was invented from scratch by James Naismith in 1891 in Springfield MA. He had a very specific, and limited, purpose: to provide an athletic activity, more enjoyable than calisthenics, that could be engaged in during the winter months, indoors, when it was not possible (in New England) to play baseball or football ...

Naismith's needs were specific, too. He was an instructor in physical education, attending the International Young Men's Christian Association Training School at Springfield MA. His orientation was towards physical fitness. The competitive side of athletics was, for him, a stimulant that made exercise more pleasurable and attractive, not an end in itself - and certainly not the raw material for entertaining spectators. His ideals were those of the participant and the amateur,and his search was for an indoor game that groups of men could play with a great deal of exertion in a small place.

So, in his little gymnasium which had a running track circling the floor like a balcony, he hung two peach baskets, one at each end; he got a soccer ball; and he divided his class (18 men) into two teams. The idea was to throw the ball into the basket. The rules of play were almost automatically determined by the conditions. Purposeful blocking and tackling couldn't be allowed on a wooden floor, and would make progress impossible anyhow; but unopposed running with the ball in such a small space would make the offense unstoppable.

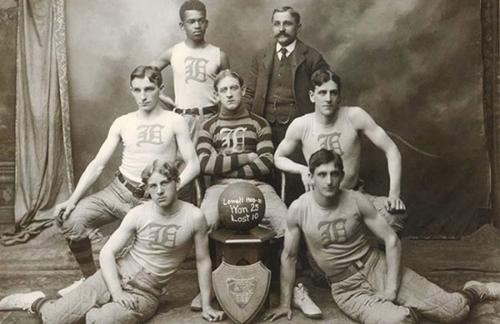

L-R: James Naismith, YMCA basketball team c. 1900

The problems were built in from the start, too: exactly how much body-contact constituted a foul? When did a legal dribble slip over into "traveling"? When was the offensive player responsible for contact and a foul, and when the defensive player? These intrinsically borderline judgments, always affected by angle o vision and the subjective reaction of the observer, put a tremendous burden on the referee. His decisions, inevitably had a greater effect on the outcome than in other games, and this feature of basketball has never been overcome with complete satisfaction.

However, as an exercise activity, with not too much attention to the score, it proved to be ideal, and an immediate hit with the participants. Within three years it had been introduced from coast to coast, by graduates of the Springfield classes and by active letter writing. Many who tried it immediately became addicts, and rules were quickly put into stable and standardized form.

By 1895, various YMCA teams were holding regional tournaments, and basketball players were taking the game into high schools and colleges. To the participants, the sugar-coating had become the main course.

And it was this instant popularity that generated serious difficulties. Naismith had done far more than he had imagined. The game was so fascinating that its competitive aspects could not be kept under control. The good athletes who tried it became, like all good athletes, intent on winning, and tournaments added to the incentive. With victory prized so highly, the game became rough, since there were few experienced referees and no effective ruling body. It became too rough to be looked upon, by YMCA administrators, as healthful exercise; nor could the presence of an increasing number of spectators, reacting passionately to their rooting interests, be fitted in to the YMCA program. ...

The YMCA, therefore, embarked on a campaign of de-emphasis, only a few years after popularizing the sport it had invented. It discouraged the formation of club teams, and the conducting of tournaments.

These ephemeral leagues were plagued with profound difficulties, mostly arising from poor organization and insufficient funding. For example, in the absence of binding contracts, players routinely jumped from team to team, selling themselves to the highest bidder, oftentimes right before a game. Within the same league, some players performed for as many as five different teams each season. Nor was it unusual for entire teams to jump from one league to another. The most damaging result of the unstable rosters was that fans were unable to maintain a rooting interest in their local ball cllubs, and attendance inevitably dwindled as each season progressed.

Pawtucketville Athletic Club in the New England Professional Basketball League

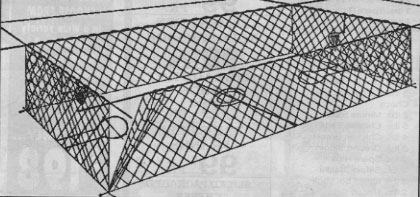

The first basketball "cage" was in Trenton's Masonic Temple.

Overall, the pro game was mostly an exercise in brute force and dirty tricks that appealed only to the most bloodthirsty of sports fans. Old-timers compared it to ice hockey played on wood and without skates. The college game, on the other hand, was cleaner and, because of the emphasis on finesse, was considered to be much more skillful than the pro version.

Gotta Have Him

The Last Pass: Cousy, Russell, the Celtics, and What Matters in the End,

Gary Pomerantz (2018) It is 1957. Red Auerbach, the Celtics coach, is trying to decide whether to draft Bill Russell. If Russell was everything he seemed to be, he could remake the Celtics, in particular the team's fast break. Long, lean, and springy, Russell on defense became like a Venus flytrap, thwarting shots that flew toward him. In college, Russell's defense and shot blocking proved game altering. His University of San Francisco coach, Phil Woolpert, said that in one game against Cal-Berkeley, Russell blocked 25 shots. By the second half of many games, opposing shooters weren't the same; Russell's psychological warfare reduce them to dupes, their shooting confidence gone. Auerbach understands this, just as he understood that he needed a center to battle the Knicks' Harry Gallatin and Sweetwater Clifton and Syracuse's Johnny Kerr and Dolph Schayes. Ed Macauley couldn't win those battles. He was too thin. The Celtics had lost in the playoffs for six straight seasons to those two teams in large part because Auerbach didn't have a rugged big man. He also needed someone to get [Bob] Cousy the ball on the fast break.

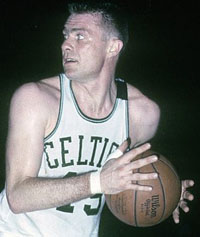

Auerbach had friends watching Russell, and he strafed them with a thousand questions. As a rebounder, he heard, Russell had long arms, inside quicker. A master of positioning, Russell always seemed in the right spot for a rebound. Auerbach listened to the criticisms as well: Russell was not a good shooter or ball handler, and he seemed moody ... It was widely known that Abe Saperstein wanted Russell for the Globetrotters, reportedly offering as much as $50,000, but Russell wasn't interested. Russell was not a conventional center; he wasn't a primary scorer. Not everyone was convinced he would became an NBA star. Auerbach brushed aside such thinking. Russell, he believed, was a winner: He had just won consecutive NCAA championships and, at the moment, was riding a 56-game winning streak at USF. All eight NBA teams knew Russell was available in the draft. Even though he played beyond the media spotlight in the Far West, he would not slip through any cracks, not at nearly 6'10". Auerbach told [owner Walter] Brown the Celtics had to have him. The trouble was, Boston had the sixth pick in the draft, much too low to get Russell. Besides, the Celtics intended to give up that first-round pick to select Tom Heinsohn of Holy Cross, the NCAA's fourth leading scorer, as a territorial selection; in this way, the NBA allowed teams to select a popular college player in their region, within a radius of 50 miles, figuring that would help at the gate. ... Auerbach could never undo what Harry Frazee had done to Boston sports by selling Babe Ruth in 1920, but by acquiring Russell in the 1956 NBA draft he would bring to the Hub a luminious new star whose effect on his sport would be nearly as dramatic as the Babe's on his. What Ruth did for baseball with his offense, Russell would do for basketball with his defense. Both became the foundational piece of a dynasty.    L-R: Red Auerbach, Bill Russell, Walter Brown, Tom Heinsohn No one knew for certain what was to come on draft day, April 30, 1956. Rochester had the first pick. Auerbach knew that Royals owner Lester Harrison was bleeding money, and that his team already had an excellent big man, Maurice Stokes, an African-American all-star who as a rookie had averaged nearly seventeen points per game. Russell was said to be seeking $25,000 per season, probably too rich for Harrison's blood, Auerbach thought. Besides, Harrison needed a guard and privately told Brown that he wanted Duquesne’s Sihugo Green with the draft’s first pick. St. Louis picked second. Here, Auerbach thought, was his opportunity. He knew that Russell didn't want to play for the Hawks, an all-white team in the league's southernmost city. Auerbach negotiated a deal with his old boss, Ben Kerner, who had moved his Hawks from Tri-Cities to Milwaukee to St. Louis: Auerbach would trade Macauley, a seven-time all-star, popular with Boston fans and with Brown, in return for Russell, who would be selected with the draft's second pick. Much as he enjoyed playing for the Celtics, Macauley, a St. Louis native, wanted to play for the Hawks because his young son had been diagnosed with spinal meningitis and Macauley needed to be closer to home. Kerner pondered the offer. He wanted more. He wanted Macauley and Cliff Hagan, an all-American from Kentucky who had been fulfilling his military obligation and had yet to play for the Celtics but now was ready to go. Auerbach nearly choked on his cigar. Macauley and Hagan? That's a kick in the head! He desperately wanted Russell, and Kerner knew that, so Auerbach and Brown agreed to it. Preparing for all possibilities, a few weeks before the draft Auerbach and Brown secretly met at Boston Garden with Kerner and his coach, Red Holzman, and agreed that if Rochester changed its mind and took Russell with the first pick, then St. Louis would choose another big man and send him to the Celtics. On draft day, Auerbach's insides churned. But when Rochester took Green, the Celtics' coach reveled in his great fortune: Russell was his. Then, in the second round, with the thirteenth pick overall, the Celtics chose Russell's USF teammate guard K.C. Jones. In one draft, Auerbach obtained three future Hall of Famers, a feat that hasn't been equaled by an NBA team in the more than sixty years since. Of course, in so doing, he traded away two future Hall of Famers in Macauley and Hagan. "A shrewd maneuver," the Globe's Herb Ralby wrote of the Russell acquisition. In the Boston Evening American, Larry Claflin went a step further, praising the Celtics for "shocking the basketball world.” Preparing that fall with the U.S. Olympic team for the Melbourne Games, Russell played an exhibition at the University of Maryland. Auerbach and Brown showed up to see their new game changer for the first time. Russell played terribly. Auerbach thought, What did I do? If this was the real Russell, he decided, I’m a dead pigeon. That night, after the game, Russell apologized to Brown and Auerbach, saying he had never played so poorly. "I am much better than that. It will never happen again," Russell promised. Auerbach pulled aside Brown and told him that he'd never heard a young player apologize in this way. A classy kid, Auerbach thought. He recalibrated his thinking, telling Brown, "Maybe there is something here."

|

On the one side, you've got the folks who oly want to know: who is the best player in the league? That's it. That's your answer. When you find him, you've found your MVP. No matter how good or bad his team is.

On the other side, the criteria is a bit different: which guy, if taken off his team, would cause his team to absolutely crumble? This side believes you must take into account the team's position in the standings. If said team is horrendous, then its best player isn't all that valuable. ... They're the people who believe there's a reason why it's MVP and not MOP (Most Outstanding Player). That V stands for Valuable, and to figure out who that is, they've got to go a little below the surface.

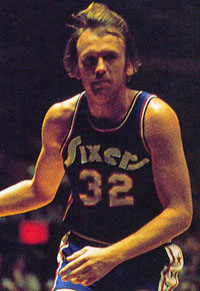

And for all their efforts, we'd like to present them with this treasure of a should-have-been-MVP example: Billy Cunningham.

Any good argument needs background info, and here's ours: In 1970-'71, the Philadelphia 76ers went 47-35, good for second in the NBA's newly formed Atlantic Division. Clearly the team's best player was Cunningham. He averaged 23.0 ppg. He led the team in rebounding ... and he was second on the team in assists ...

The following year, the Sixers traded G Archie Clark to Baltimore for Kevin Loughery and Fred Carter. They also obtained Bob Rule and Bill Bridges in trades. With all the new faces on this team in transition, the record suffered at 30-52. But the future looked bright, especially with Cunningham shining brightly. ...

This is where you will start to see how this situation is so appropriate to the argument: Billy Cunningham abruptly left the 76ers after the 1971-'72 season to join the ABA's Carolina Cougars, and whatever part of the dam he had been holding together was suddenly a leaky - no, gushing - mess. The 1972-'73 Sixers - sans Cunningham - were a disaster.

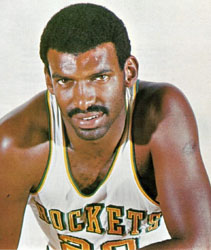

L-R: Billy Cunningham, Roy Rubin, John Q. Trapp

Rubin's Sixers lost their first fifteen games, and put themselves into a bigger hole than the Grand Canyon. From those First Fifteen, "it was clear we were the league's universal health spa," Carter explained. "If teams had any ills, they got healthy when they played us."

As you might be able to gather, the team didn't have much respect for Roy Rubin. Still, what John Q. Trapp did on December 20 was way over the line. In a 141-113 blowout loss, Rubin was trying to keep his troops fresh as they were run up, down, around and over by the Pistons. But when he sent a substitute in for Trapp, John Q. refused to come out of the game. He apparently wanted his garbage-time minutes. Badly. When Rubin insisted that the forward heed his instructions, Trapp told the coach to look behind the Sixers' bench. There, the legend goes, one of Trapp's consorts opened his jacket to reveal a handgun. Rubin gulped, turned back to the court, and left John Q. Trapp in for the rest of the game. No use getting killed just to hold a team under 140 points. ...

At the All-Star break, Philly got rid of Rubin. They named Kevin Loughery player-coach, and one of his first orders of business was to release John Q. Trapp. Which didn't change things too much - except for the coach's on-court safety level.

Still, the city of Philadelphia watched while its team struggled almost as much without Rubin as it did with him. It couldn't have happened to a more impatient bunch of fans. Philly sports boosters are known for their "What have you done for me in the last third seconds?" attitudes. They boo without must provocation; they curse with even less. ...

Maybe it's not all bad that these are the people who had to sit through an entire season that had the rival Celtics finishing fifty-nine games ahead of them in the standings. ...

Somehow, in February, the Sixers reeled off five wins in seven games. It's hard to come up with an explanation for it, so let's just move on. Because immediately following that five-of-seven streak came the thirteen losses to run out the year. ... Final record: 9-73.

And there's the real story. Billy Cunningham was so important - so valuable - to his franchise, that when he left, the rest of the players regressed into the Worst Team in the History of the NBA.

|

This article appeared in the program for LSU's first football game of the 1972 season.

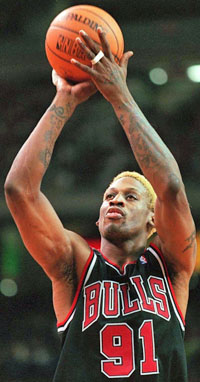

That was also the first year of the LSU Assembly Center. Dale Brown teaches a fast break style of basketball. And, it's his way of life also.

Named last March to guide the Tigers back to national basketball prominence, Dale has utilized every available waking moment toward that goal, and his pace is somewhere between a brisk jog and an all-out sprint. "I jumped at the challenge here at LSU," Brown explains, "and I knew we would have to get out and promote. Once we get into practice in October, our time will be limited in getting out to meet people, so we have gone to them every chance we have had since arriving. We want the players, the coaches, and the people of Louisiana to know us, to know what we are striving for, and to join with us in our task to make basketball at LSU a success again." Brown has coined his effort the "Tiger Safari," and along with associate coach Jack Schalow and assistant coach Homer Drew, the legion of followers grow daily. They held a clinic for the youngsters, a free throw contest for all ages, and in their journeys have given away over 800 nets throughout the state. All while recruiting Louisiana talent to play for the Purple and Gold.   Dale Brown and the Assembly Center in 1972 You might come upon the coaches anywhere, strolling through the campus introducing themselves to students and faculty, at your front door where they give you a net for that goal you have in your driveway; or at any number of civic, fraternal, or church gatherings where they have gone to tell of their goals for LSU basketball and asking you to be a part in it. "We know we have the finest facility in college basketball in the Assembly Center; we have tradition of great basketball in seasons past; and we know from talking to the wonderful people of this state they want LSU up there at the top," Brown points out, "so we are very pleased with the reception we have been given, and we know in time the goals will be attained. When that comes about, it will have been accomplished with the help of the people throughout the state, and we will all share in it." Brown is a 110 percenter, and he promises his teams will be too. "I can't promise victories and success right off the mark, but I promise when people come to see us play, they will leave saying to themselves, 'that LSU team hustles every moment, they play with desire, and they are unselfish.' We won't be ashamed of any effort if the people can say that," Brown vows. "Support this young team we will have this winter, stick with them in the tough times we will face, and the taste of success will be that much sweeter when it comes," adds Brown. You like a challenge? Then come aboard and "Join the Tiger Safari." |

The Biggest of the Big Three

The Big Three: Larry Bird, Kevin McHale, and Robert Parish: The Best Frontcourt in the History of Basketball, Peter May (1994)

It was August 18, 1992. Larry Bird picked up his telephone and placed a call to Jill Leone in Florida. For years, she has been the woman who has had the thankless job of getting Larry here or there, making sure the man in Maryland has a signed congratulatory telegram from B for his wedding, and so forth. ... She keeps track of Bird's whereabouts - no small feat.

"I'm retiring," he told her. Bird was by himself. He had sent his wife, Dinah, back to their home in West Baden, Indiana, fearing she would have a hard time dealing with all the emotions of this moment. She, in fact, had wanted her husband to make this announcement a year earlier, after an unrelenting back injury forced him to eat his meals on the floor. But Bird had felt so good after an off-season operation that he returned for another year and even signed a two-year contract extension work $8 million. ... The day in Boston was fittingly overcast and rain pelted the streets. Some hoop historian will undoubtedly find some metaphorical significance in that ... Bird had earned close to $30 million in salary alone in his 13 years with the Celtics, including $7.07 million in his final year. Had he merely shown up and played in 60 games in the 1992-93 season, he would have made another $8 million. But he couldn't do it. In fact, he had deliberately backdated his retirement better because he had been due to receive $3.75 million for the 1992-93 season on August 15. He was raised to work for his money, an admirable quality that never deserted him. In addition, he had done quite well with the vast sums he'd accumulated over the years. "No one is going to have to throw a benefit for Larry Bird," said Celtics GM Red Auerbach. On the way to the Boston Garden for the retirement news conference, Bird was nervous. His main hope was that he wouldn't get too emotional, he told is agent Bob Woolf. "I hope I don't break down and I can get through this," he said.   L: Larry Bird in his heyday; R: Dave Gavitt, Bird, and Red Auerbach at Larry's retirement Bird had come to the unavoidable conclusion that he had to retire during a four-and-a-half hour meeting with Celtics senior executive vice-president Dave Gavitt a week earlier. His back, which had forced him to miss 59 games the previous two years, was not going to get well enough for him to continue playing. Surgery had given him another year, but it was a dysfunctional one at that. Then, when the back acted up again in April, and the team went on a tear without him, people - including some players - began to question Bird's value to the team.

The back was so sore that Bird couldn't even make it through the Olympic qualifying tournament in Portland, the Tournament of the Americas, a week-long series of games that resembled the Joffrey Ballet more than the NBA in terms of contact and physical play. It was then that Larry Joe Bird, a three-time MVP and one of the game's greatest players, decided he had quite likely played his last game. "I just remember lying on my bed in Portland," he says, "and saying, 'God, just get me through the Olympics and I'll give this up and move on to something else.'" He got through the Olympics. His baby son, Connor, kept him awake at night, but the U.S. team was so dominant his presence hardly mattered. Even his inclusion on the team seemed more of a related honorarium than a reflection of his present basketball expertise or stature. At one time, it was unthinkable not to include Bird as one of the two forwards on an All-NBA team. But he hadn't made one since 1988, and his participation in the Olympics was akin to John Wayne getting the Oscar for True Grit. Dave Gavitt, who oversaw the selection process of the aptly named Dream Team, noted, "When healthy, there aren't ten better than Larry." But Bird wasn't healthy, hadn't been for years, and now, finally, the sport that had sustained him for the last 17 years, the sport that had made him a multimillionaire and an idol to thousands, the sport that turned him from a southern Indiana introvert into a global celebrity, would no longer be the focus of his daily life. Quite naturally, he found this troubling. The night before the announcement, he went back to his house in Brookline and contemplated his brilliant career in between Kleenex and beers. Bird sat alone and remembered. There were plenty of flashbacks. Game 6 against the Houston Rockets in 1986, a game that clinched the Celtics' 16th NBA championship, the third and last for Bird. The famed fourth-quarter shoot-out with Dominique Wilkins in the 1988 Eastern Conference semifinals. The masterpiece against the Knicks in Game 7 of the 1984 conference semifinals, a performance so dominating that Hubie Brown, then the coach of the Knicks, still remembers it as Bird's transformation from star to superstar. The fight with Julius Erving. The game-winning basket against the 76ers in 1981 conference finals. The first ring in 1981. The steal against the Pistons in 1987. The 60-point game against the Hawks in New Orleans. The second championship in 1984. He's lucky he got to sleep at all. ... "I felt going into the Olympics, that he pretty much had decided he couldn't do it," Gavitt said. "He certainly had the desire. And the skills. I realized then that his back just wasn't going to let him play. But I think he actually was having a very difficult time getting himself to actually say it." The two got together for dinner in Portland and Bird finally did at least allow for the possibility that his NBA career was over. "All I'm hoping is that there is one more month in my back," he told Gavitt. Then he said, "If I can't play, what the hell am I going to do?" ... Then came the next question. What did he want to do? Coach? Bird wouldn't even consider it. A nine-to-five job with a jacket and tie? Bird, one of the game's most gifted creators and perhaps the greatest passing forward of all time, a player who, Gavitt noted, played the game better than anyone "from the shoulders to the top of his head and from his wrists to his fingertips," can't even tie a necktie. So that was out of the question. Finally, Gavitt handed Bird a slip of paper and told Bird to write down the job description. Bird did not write "special assistant to the senior executive vice-president," but that is what he became. Months later, he still didn't know what floor the Celtics' office was on when he visited one day. The job would mostly be advising Gavitt on players seen on tape and representing the Celtics at clinics and functions, something he never did while playing. Some of his teammates felt the position was simply a glorified thank-you. Robert Parish was among them. "I heard he was going to go around speaking," Parish said. "Knowing Larry, we'll see how long that will last." ... The actual retirement announcement came at midday, and all three local TV stations went live to the site. ... Bird looked worn, tired, and emotion ravaged. Over the years he had grown more comfortable with the media, and he even enjoyed sparring with them on occasion. He was not looking forward to this, however. "This is a little tough today, but we'll try and get through it as best as we can," he said. "It's a very emotional day, but it's not really a sad day. ..." He touched on his agonizing week in Portland, when he made a pact with the Higher-up. He got through the Olympics, which was all he wanted, right? "Well, I thought I could lie to Him and maybe play a little more," he said. His sense of humor was still there, and he needed it. "The reason I stand up here and try to make jokes is to keep myself from crying. I'm not going to cry today. This is a special day for me." That was it. ... He accompanied the executives to the Celtics' offices, where sandwiches were waiting. Bill Russell called to offer his thoughts. Bird got on the phone and called him "Mr. Russell." |

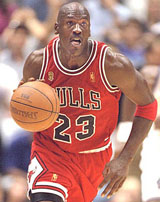

The Bulls arrived to play for the hamburger championship of the world, as they often did these days, with all the fanfare of a great touring rock band. They were the Beatles of basketball, one writer had said years before, and in fact they flew over in the 747 normally used by the Rolling Stones for their tours. There had been a time when Michael Jordan had regarded France as a kind of sanctuary, a place where he could vacation and escape the burden of his fame, sitting outdoors in front of a cafe and savoring the role of anonymous tourist. His appearance on the Olympic Dream Team five years earlier and his subsequent mounting international fame had ended that. His gross income had more than doubled, but he had lost Paris; he was as recognizable and as mobbed here as anywhere else. Huge crowds waited outside his hotel all day long hoping for the briefest glimpse of the man French journalists called the world’s greatest basketteur. At the games themselves, the French ball boys seemed unwilling to serve their own team and wanted to work only with the Bulls. Some of the French players inked Michael’s number, 23, on their sneakers as a means of commemorating their brush with greatness. At Bercy, the arena in which the games were played, copies of his uniform jersey sold for the equivalent of a mere eighty dollars.

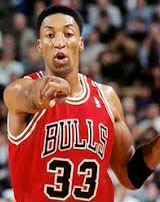

L-R: Michael Jordan, Dennis Rodman, Scottie Pippen

Stern, surrounded by most of the NBA executive staff and all sorts of McDonald’s executives, had a wonderful time. Almost everybody in the basketball structure who was anybody had come. There was one notable exception, and that was the absence of Jerry Reinsdorf, the Bulls’ owner, who rarely showed at things like this. Stern had pushed Reinsdorf to come and enjoy some nachas, a Yiddish word for pleasure, but that kind of nachas did not seem to appeal to the Bulls’ owner, a man who seemed to prefer his privacy to the semi dubious glitter and adulation that even an owner could be a part of at occasions like this. In addition, there had been a good deal of speculation at the last moment among the NBA people as to whether one other VIP, Dick Ebersol, the head of sports for NBC, would come. There was a powerful rumor sweeping Paris that even though the McDonald’s championship coincided with the start of the World Series, Ebersol, whose heart was said to belong to basketball rather than baseball, would come to Paris instead of sitting in some highly visible box seat being seen by his own cameras at the Series. Appropriately, given the symbiotic relationship between television and big-time sports, Stern and Ebersol were very close. Ebersol was wont to call Stern his boss, and Stern was wont to call Ebersol his. Stern was the most passionate and sophisticated of modern imagemakers, and it was Ebersol’s company that determined which images went out to the nation. Stern understood, as not everyone in the world of sports did yet, that image was more important than reality in their business. He monitored the league’s coverage of his sport very closely, and often seemed to take quite personally any departure on the part of the broadcasters and their cameras from what might be considered an image upgrade. In fact, when he had first ascended at the NBA, at a time when the league’s image was still largely negative, he had been famous for calling network executives on Monday to complain about any image downgrade that might have taken place on Sunday.

Both Ebersol and Stern had a shared stake in the good name and the public image of basketball, especially in the public behavior of its best players, and the two men had worked closely in a collaboration that had seen a dramatic rise in the popularity of the sport, and in time in its network ratings as well. That the question even arose of whether Ebersol would bag the World Series for exhibition basketball games against weak opponents in a foreign land for a cup handed out by a hamburger company showed how much the fortunes of the two sports had changed in recent years. This World Series, between Cleveland and Florida, did not, as it was about to begin, seem to the average fan a particularly tantalizing one; it seemed to lack the sense of a traditional rivalry, or at the least, some degree of geographical animosity. It pitted a Miami team, one that few fans knew very much about, against a Cleveland team that was talented but not well known. Neither team, to the general sports public, had yet created any kind of persona. There was no rivalry, neither historic nor geographic, between the two teams. Eventually Ebersol had stayed in America to watch the Series. Stern had teased him about that—“Dick, if you want to stay back in the States and watch the lowest-rated World Series in history, feel free to," he had said. (Stern was wrong: It was not the lowest-rated World Series; the one in 1993, when for the first time the NBA Finals had been rated higher than the World Series, was.)

College Basketball Scandals - 1

The Last Temptation of Rick Pitino: A Story of Corruption, Scandal,

and the Big Business of College Basketball, Michael Sokolove (2018) The 2017 scandal involving apparel companies was not the first scandal in college basketball.

With his ten NCAA championships in the 1960s and 1970s, his innovative methods, and his mentorship of such stars as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Bill Walton, the late UCLA coach John Wooden is college basketball's most revered figure. The John R. Wooden Award goes to the nation's top player each year. The basketball court at UCLA's iconic Pauley Pavilion is named for Wooden. In 2003, President George W. Bush honored Wooden, then ninety-two, with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor.

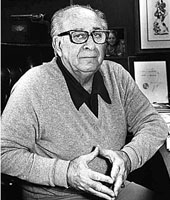

But in addition to being the greatest coach in the game's history, Wooden is the prototype for every coach since who has tried to cover himself in a cloak of deniability. On the day after he died in 2010, the Los Angeles Times wrote, "If Wooden was the father figure of UCLA basketball, Gilbert was its shadowy one." The reference was to Sam Gilbert, a builder in Los Angeles who was close to Wooden's players. An investigative series the paper published in 1981 called Gilbert a "one-man clearinghouse" who helped players get cars, clothes, airline tickets, scalpers' prices for tickets, and even, on occasion, abortions for their girlfriends. A former NCAA investigator said he had looked into Gilbert's involvement and "could have put UCLA on indefinite probation" but was told to drop his case. Even back when the story was published, it was not exactly news to the basketball cognoscenti—Gilbert's relationship to the UCLA program had been an open secret—and the allegations were not startling to Wooden. The newspaper wrote that Wooden was wary of Gilbert but generally turned a blind eye. (Gilbert was indicted in 1987 on racketeering charges by prosecutors, who were not aware that he had died four days earlier. The case centered on a marijuana smuggling ring and was unrelated to his involvement with UCLA basketball.) "Maybe I had tunnel vision. I still don't think he's had any great impact on the basketball program," Wooden commented a half dozen years after he had retired. He seemed to argue that it may be better not to know certain things. "There's as much crookedness as you want to find. There was something Abraham Lincoln said—he'd rather trust and be disappointed than distrust and be miserable all the time. Maybe I trusted too much." The two reporters who worked on the series, Mike Littwin and Alan Greenberg, would later write, "Wooden knew about Gilbert. He knew the players were close to Gilbert. He knew they looked to Gilbert for advice. Maybe he knew more. He should have known much more. If he didn't, it was only because he apparently chose not to look."    L-R: John Wooden, Sam Gilbert, Clair Bee It is hard to imagine now, but in the years before World War II and into the early 1950s, Long Island University was a national power in college basketball, the UCLA of its era. Its team won the National Invitation Tournament, in Madison Square Garden, in 1939 and 1941, when the NIT was a far more important event than the NCAA tourney, and LIU had one winning streak of 43 games, another of 38. Its coach, Clair Bee, wrote the introduction to James Naismith's only book on basketball, mentored a young Bobby Knight, and was an early proponent of the NBA's 24-second shot clock. When he died in 1983, the New York Daily News sports columnist Mike Lupica wrote, "The story of the old man's life is merely the history of basketball in this country." Continued below ...

|