John Wooden: They Call Me Coach as told to Jack Tobin (1972)

Wooden recalled his high school basketball career at Martinsville High School IN.

During my junior year we won the state title by beating Muncie Central, 26-23. I remember that not so much for the victory but for the beautiful silver Hamilton pocket watch that the people of Martinsville gave to each of us on the team. It's a fine watch, and I keep it at home now under a little glass bell chime. It runs as well as it did the day I got it.

Usually you would think that the championship would be the important memory of my high school career. But actually, it is the defeat in the championship during my senior year that takes the honor. Again, we were playing Muncie Central. With moments to go, we were ahead, 12-11. A Muncie player turned his ankle and called time out. Since they had used their allowed three times out, it was a technical foul. We had the ball when time was called. When you shot the tehnical, the ball went back to the center jump if you made it. I was captain and elected to refuse the shot, thereby keeping the ball. Curtis leaped off the bench yelling, "We'll shoot it, we'll shoot it."

I argued, because under the rules then, we had the ball. And by keeping it I knew that Muncie could not get it back before time ran out. I could keep it on the dribble alone and we'd win, 12-11, for back-to-back championships.

Curtis prevailed. I shot and missed, and the ball went back to the center jump. In those days, the center could tip to himself. Charlie Secrist, the Muncie center, tipped the ball behind him, grabbed it and in a wild, sweeping underhand motion arched the ball toward the basket. To this day, it is the highest arched shot I have ever seen. It seemed to go into the rafters and came straight down the middle of the basket, hardly fluttering the net.

Indiana basketball buffs still talk about that game. They'll tell you that it ended just as the ball dropped through the basket. I have personally heard the story from more people than Butler Fieldhouse could ever hold. Actually, what happened was that I called time as the ball came through the basket. Knowing Muncie would look for me to shoot, Curtis set up a play with me as the decoy. The center tipped to me, a forward screened for the center who got wide open, I faked a shot and passed to him underneath the basket, and he laid the ball up on the board. In doing so, he gave it a little English - it went around and around and around and then out. A forward was right there, but he was so confident the ball was in that he was jumping up and down in jubilation and wasn't positioned to rebound. When he saw it spin out, all he could do was bat it back up, but it didn't go in. It seemed like a disastrous turn of events at the time but by summer vacation the hurt had worn off a bit.

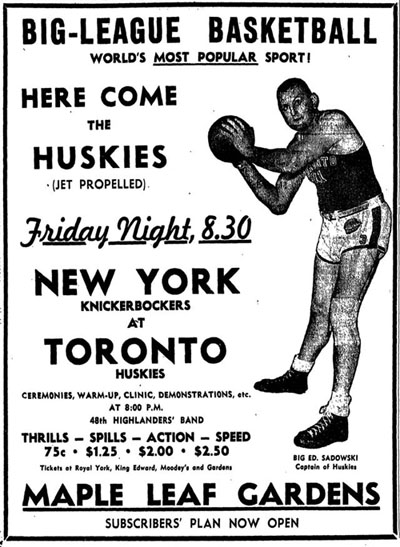

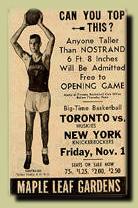

The blitz began on Monday, October 28, 1946 - four days before the Toronto Huskies were scheduled to make their maiden appearance - when a full-page notice appeared in the Toronto Globe and Mail encouraging readers to purchase season tickets for all of the Huskies' games while they were still available. "Make no mistake," the ad advised, the Huskies were destined to be the latest sports craze, eventually rivaling the Maple Leafs and the Argonauts, the city's beloved entries in the National Hockey League and the Canadian Football League, respectively. "Get your seats early."

|

|

Besides, the war was over. Hitler was dead, and the A-bomb had blown Japan to smithereens. The economy was still booming, the vets were back home, and just about everybody had plenty of spare change to spend on fun and games.

Also, since the Argos and the Leafs always played to standing-room-only crowds, the Huskies offered the only readily available "big-league" sports ticket in town. Even more promising was the fact that the rest of the teams in the newly hatched Basketball Association of America wouldn't commence playing until the following night, November 2, 1946, a prized Saturday date that was already co-opted in Toronto by the Leafs. So, not only would the upcoming roundball season showcase the first professional basketball game in Toronto (or, for that matter, in Canada), but also it would mark the official onset of the BAA. How could the Huskies miss?

But even before the visiting New York Knickerbockers crossed the border, they already had their doubts. October 30, 1946, was cold and brisk when their train was halted at the Niagara Falls crossing ... the uniformed officer couldn't help noting their extraordinary size, and he asked on the players, "What are you?"

The team's coach, Neil Cohalan, proudly responded: "We're the New York Knicks."

The inspector was perplexed. "I'm familiar with the New York Rangers," he said. "Are you anything like them?"

Instantly deflated, Cohalan said, "They play hockey. We play basketball."

Before moving on to the next car, the inspector offered his opinion. "I don't imagine you'll find many people up this way who understand your game - or have an interest in it, either."

Even so, the advance advertising paid immediate dividends, as the opening crowd at the Maple Leaf Gardens numbered an impressive 7,090 (none of whom was taller than Nostrand). Also on hand were Ned Irish, the influential boss of the Knicks, and Maurice Podoloff, the BAA's commissioner.

At eight o'clock, after both teams completed their warm-ups, the Huskies conducted an educational miniclinic wherein they demonstrated the variety of shots the novice fans would be seeing. The repertoire consisted of right- and left-handed layups and hook shots, two-handed set shots, and underhanded free throws. Since none of the players on either team was a practitioner of the newfangled one-handed shots, they were totally ignored.

Adding to the problem that elements of the game were new to most of the fans on hand, the hometown team was unfamiliar with the court itself. The only time the Huskies had seen the court had been during a brief morning practice, and both the see-through Plexiglas backboards and the playing surface were unusual.

Only a handful of on-campus courts in the States were similarly equipped with the latest development in backboards. Even if they were a boon to the spectators stationed high up in the baseline seats, the glare and lack of a solid shooting background was profoundly distracting to the players.

The court itself was a portable apparatus that had been laid directly on the ice surface. The footing in the practice session had been adequate, but with so large a crowd, the elevated temperature in the building created some condensation on the floorboards, and the surface could be treacherous, particularly near the out- of-bounds lines. ...

Cohalan's counterpart was "Big Ed" Sadowski, a player-coach who measured an imposing 6'5" and weighed 270 pounds. ... A scowling brute of a man with close-cropped hair and a game face as belligerent as a clenched fist, Big Ed tallied most of his points with a sweeping right-handed hook shot that was virtually unstoppable. ...

Since both Gohalan and Sadowski hailed from New York, their teams played similar styles: passing, screening, cutting either to or away from the ball, slicing off the pivot for the old give-and-go, and shooting only the traditional set shots, hooks, and layups. ...

At the buzzer, the Knicks had won by 68-66. .... The Toronto sportswriters were puzzled by the game, identifying Sadowski's fouls as "roughing" and "cross-checking." Even so, the Huskies' management counted the gate receipts and dared to hope that both their franchise and the fledgling league would be a huge success.

Dolph Schayes

|

Tall Tales: The Glory Years of the NBA, in the Words of the Men

Who Played, Coached, and Built Pro Basketball, Terry Pluto (1992) Players, coaches, and officials from the 1950s reminisce Syracuse star Dolph Schayes: Syracuse had a wonderful small-town feel to it. When you played for the Nats, the whole town embraced you, like Green Bay does with the Packers or Portland with the Blazers. We thought of ourselves as the underdog, the little guy taking on the big city. Our arena had only 6,400 seats and the fans were right on top of you.

Referee Norm Drucker: You'd go to Syracuse and the fans knew you were there ... You'd be having bacon and eggs in the hotel coffee shop and some guy would stop by and say, "You're Drucker, right? You screwed us last time, don't do it again." Then you'd step on the court and look at the Syracuse bench and there was Danny Biasone. Young officials would point to him and say, "Who's that guy?" I'd say, "He owns the team." Then I could see a lump in the official's throat. He was thinking, "I better not mess up or this guy will be on the phone to my boss." Referee Sid Borgia: People tell me that [Danny] was good because he didn't say much on the bench. In that building, he didn't have to. Officials deserved combat pay for working in Syracuse. Those fans were so crazy and they never believed their team did anything wrong. Syracuse C Johnny Kerr: Another reason that Danny didn't have to say anything was that [coach] Al Cervi could work the crowd. When a call went against us, he'd turn his back to the court, face the fans, raise his hands to the heavens as if to say, "Why is God punishing us with these officials?" Then the crowd would take over and shower the court with popcorn boxes and orange juice cartons. Referee Earl Strom: Their public address announcer was the worst. I'd work a Syracuse-Philly game. I'm from Pottstown, Pennsylvania, which is not a suburb of Philadelphia. But in Syracuse, they'd introduce me as "Earl Strom from Philadelphia." Right away, the crowd is on my butt. ... Syracuse would commit their sixth foul of the period and the guy would say, "For Syracuse, that's six team fouls. Philadelphia has only one." Again, the house would come down on you. ... Referee John Vanak: Syracuse knew that it was tough to call fouls on them at home. They had guys like Al Bianchi, who just loved to flatten people. Al would knock a player on his ass and almost dare you to call a foul on him and take the heat from the crowd. Back then, there were no flagrant fouls. A guy could drive the lane, Al could hammer him, they would have to call an ambulance and it would still be only two shots. Syracuse G Al Bianchi: Against the good teams, our games were wars. Boston ... boy, we always had great fights with them. Vanak: There was a game where Jim Loscutoff grabbed Dolph Schayes by the throat with about two minutes left. They both fell down, and the next thing I knew fans were spilling out of the stands. We had a riot on our hands and it took a good half hour before we got the floor cleared and finished the game. Celtics G Frank Ramsey: The Syracuse fans were out of control. They'd throw cups full of Coke, programs, even batteries at you. That place was a hockey arena with sideboards. On the night of the big fight between Dolph and Loscutoff, the fans knocked over those hockey boards to get on the court and some of the fans were hurt when they ended up under the boards. It was like a stampede. Bianchi: There was a night when the Syracuse fans tried to storm the Boston dressing room. The players slammed the doors on a few hands, breaking their fingers. Another time, the Celtics were walking off the court after a game with a police escort. A fan dumped a beer on a Boston player. Vanak: The same kind of thing happened to Joe Gushue. He was leaving the court and a fan whacked him over the head with a rolled-up newspaper. Boston C Gene Conley: Oh, their fans ... you'd stand at the foul line and they'd throw candy bars at you. The guys on the bench got bombarded the most. Ramsey: There was a night the stuff being thrown at us was so bad that the officials told all of our subs to leave the bench and stay in the dressing room - for our own safety. The coach was out there alone. When Red Auerbach wanted to make a substitution, he had to stop the game. He'd send the player who was coming out into the dressing roo with the message of who Red wanted as a replacement. Conley: Poor Frank Ramsey. To get off the court, you had to walk through a tunnel that went through the stands. The fans were all over us and one of them grabbed Frank around the neck and was strangling him. I punched the guy or Frank would have choked. Drucker: They had a fan called the Strangler. He was about 5-foot-6, maybe 220 pounds with a tremendous chest and arms. He'd run up and down the sidelines during the game and stand next to a player, screaming, "You SOB, you stink." Strom: If I had to guess, it probably was the Strangler who grabbed Ramsey. That fan got his name when he picked up [official] Charley Eckman at halftime and had poor Charley hanging by the neck. Gene Conley hated that guy. One night, we were walking off the court and Gene saw the Strangler. Gene said, "When we get near that guy, duck." We got close. The Strangler reached down from the stands to grab me, I ducked and Conley drilled the guy, knocking his lights out with one punch. Drucker: The Strangler loved to run up to the Celtics' huddle and yell things. One night, I saw him there. Then I saw the huddle open, he disappeared inside and the huddle closed around him. When he came out, his mouth was bleeding. The Celtics worked him over. Borgia: Some of my scariest moments were in Syracuse. There was a game where Syracuse was down by three points with 15 seconds left. Dolph Schayes drove the lane, dipped his shoulder, ran smack into Sweetwater Clifton, and in the same motion, he threw in a shot. All the fans thought the basket was good and Schayes would be going to the foul line for a three-point play. John Nucatola was working the game with me, and he called a charge - no basket, New York ball. |

NCAA Champion magazine March 2015, ncaachampionmagazine.org

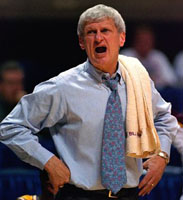

In six decades of shooting the Final Four, Rich Clarkson has shaped how we see the game.

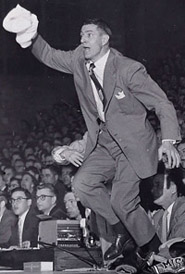

Missouri coach Sparky Stalcup put on one of the greatest displays of a coach losing it that I've ever seen in the old Brewer Fieldhouse — leaping up onto the floor and throwing towels and running up and down the sidelines. I'm busy shooting pictures of the whole thing. I made about eight or 10 of those and sent them off to the Kansas City Star.

A day later, my mother says, "The phone call is for you." It was Coach Stalcup. He said, "I want you to know that you're never welcome again in Brewer Fieldhouse." So I called the sports editor of the Kansas City Star to report on the phone call I got about these pictures. They then wrote a column about it. And then the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote an article about it, and the guy who was the sports editor at the Columbia Daily Tribune wrote one, all very critical of Sparky Stalcup, of treating an aspiring college photographer like that.

He says, "You're Clarkson, aren't you?"

I said, "Yes, sir."

He said, "We'll have to make the best of this, won't we?"

"'Fifteen minutes, time to go to work, Pete.' Basketball goes back on the shelf. ... 'Twelve o'clock, time for lunch.' 'Can I have my basketball?' Goes out into the parking lot, dribbling around through and behind cards. All that kind of stuff. Then in the afternoon I say, 'Okay, it's three o'clock. Time for a fifteen-minute break.' So then he starts doing a demo with the basketball in the drugstore. Now that ain't bad for business. He did his deal in the drugstore. Got those long aisles and he'd be dribbling down the aisles, going around women trying to get their shampoo or whatever."

Longtime sports media honcho Bud Johnson had two go-arounds with Pete Maravich, first when he was sports information director at LSU and later when he was the public relations director for the New Orleans Jazz of the NBA ... John son thus saw the Pistol in two different phases of his life, starting as a green freshman at Baton Rouge in 1966-67.

He was very young and immature when I first met him at LSU. He was very playful and very much wanted to hang out with his buddies and do things with them. After LSU football games, he and his friends Rich Hickman and Jeff Tribbett would go play basketball. While most fraternity boys would be out partying after football games, these guys would be hanging out together and playing pickup basketball.

I recall his years at LSU as his being a very frail athlete who didn't have much stamina. On those weekends when they'd play Saturday-Monday games in the SEC, and you could probably go back, look at the box scores, and see that on Saturday night he's gangbusters against Vanderbilt, and then Monday against Auburn he has a so-so ball game. Putting all the facts together, that heart defect that he had was showing itself to us, but nobody knew it. Considering his heart defect, if he had been a normal human being not playing basketball, he wouldn't have lived to be twenty-one years old. At least, that's what the medical people told me. ...

When I first met him, he was about six-four, 165 pounds. He didn't look physically imposing. At least, he didn't look like what the press clippings had made him out to be. No muscle tone. Long arms, long legs. All bones and big eyes. But God, he could handle a basketball. And I asked Press, 'Why did you give him all those drills at an early age?" and he said, "Because it gave him confidence. He was always the smallest kid on the team, and it gave him confidence he could do something nobody else could do.' And I think Press got caught up in it, because no matter what drill Press had given him, Pete had mastered it by the time Press had gotten home at the end of the day ... So he had to come up with something else to challenge Pete. So Press was challenged as well. He was giving him things for finger dexterity and various passes. Nobody else was doing that.

John Feinstein (1986)

Even though Knight was put through the humiliation of being dragged from the practice floor in handcuffs, he probably would have been judged a victim in that incident had he simply allowed the witnesses to tell the story. But that isn't Knight's way. He is completely incapable of letting an incident ... simply die a natural death. Indiana University vice-president Edgar Williams, one of Knight's best friends, describes that side of him best: "Bob always - always - has to have the last word. And more often than not, it's tht last word that gets him in trouble."

Puerto Rico was the perfect demonstration of Williams's words. In speeches long after he had left San Juan behind, Knight was still taking shots. He talked about mooning Puerto Rico as he left it, made crude jokes about Puerto Rico, and, ultimately, turned public sentiment around: instead of being the victim of an officious cop, he made himself the Ugly American. Knight thought he was being funny; he couldn't understand that many found his brand of humor offensive. ...

Because of Puerto Rico, Knight thought he would never be named Olympic coach. ... When the selection committee met in May 1982 there were two major candidates: Knight and John Thompson, the Georgetown coach. It took three ballots, but the committee named Knight. It was testimony to his extraordinary ability as a coach that, in spite of Puerto Rico and the aftermath, he was given another chance. ...

Once he had the job, Knight was a man with a mission: to destroy the hated Russians, to make sure the world knew that the U.S. played basketball on one level and the rest of the world on another. ....

But at the last minute, fate and politics tossed a giant wrench into his plans: the Russians, getting even for Jimmy Carter's 1980 boycott in Moscow, decided to boycott Los Angeles. Even after the April announcement, Knight kept preparing for the Russians right up until the day in July when it was no longer possible for them to come. Ed Williams, watching his friend during this period, saw him as a general who had prepared the perfect battle plan, trained the troops, raised his sword to lead the charge, and then saw the enemy waving a white flag. ...

But Knight never let himself approach the Olympics that way. For one thing, he couldn't afford to; if, by some chance, he slipped and his team lost to Spain or Canada or West Germany, he would never live it down. He knew how much Henry Iba, the coach of the 1972 Olympic team, had suffered after the stupefying loss to the Russian in Munich. Knight thought Iba a great coach, and looked up to him. It hurt Knight to hear people say that Iba, who had coached the U.S. to easy gold medals in 1964 and 1968, was too old to coach that team and had, because of his conservative style, cost the U.S. the gold medal. Knight was angered by the loss in Munich because he thought the U.S. had been cheated. ...

And so, he drove everyone connected with the Olympic team as if they would be facing a combination of the Russians, the Bill Russell-era Boston Celtics, and Lew Alcindor's UCLA team. The Olympic Trials ... were brutal. Seventy-six players practiced and played three times a day in Indiana's dark, dingy field house ...

The players were pushed into a state of complete exhaustion; by week's end, Knight had what he wanted. Some wondered why players like Charles Barkley and Antoine Carr weren't selected while players like Jeff Turner and John Koncak were. The answer was simple: Knight wanted players who would take his orders without question. ...

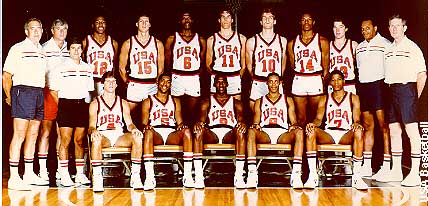

It was still a team of breathtaking talent: Michael Jordan ...; Patrick Ewing ...; Wayman Tisdale ...; Sam Perkins ...; Alvin Robertson ...; and Steve Alford, Knight's own freshman point guard. ...

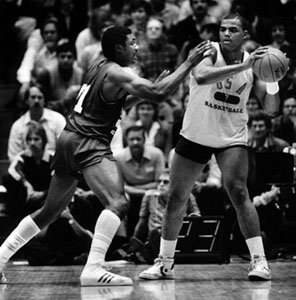

L: Karl Malone and Charles Barkley at '84 Olympics Trials - neither made the team.

R: Michael Jordan in action

The preliminary round of the Olympics - five games - was a mere formality. In the quarterfinals against West Germany, they were sloppy but still won by eleven, their closest game. They annihilated Canada in the semifinals, leaving only Spain, a team they had beaten by 25 points in preliminary play, between them and the gold medal. ...

When Knight walked into the locker room for his final pep talk, he was ready to breathe fire. ... But when he flipped over the blackboard on which he would normally write the names of the other teams' starters, he found a note scotch-taped to the board. It had been written by Jordan: "Coach," it said, "after all the shit we've been through, there is no way we lose tonight."

Knight looked at the twelve players and ditched his speech. "Let's go play," he said. Walking onto the floor, Knight folded Jordan's note into a pocket (he still has it in his office today) and told his coaches, "This game will be over in about ten minutes."

He was wrong. It took five. The final score was 101-68. Spain never had a chance. The general sent his troops out to annihilate and they did just that. When it was over, when he had finally reached that golden moment, Knight's first thought wasn't, I've done it, I've won the Olympic gold medal. It was, Where is Henry Iba? Knight had made certain the old coach was with the team every step of the way ... Now, when the players came to him to carry him off the floor on their shoulders, Knight had one more order left for them: "Coach Iba first." And so, following their orders to the end, the players carried Henry Iba around the floor first. Then they gave Knight a ride. Then, and only then, did he smile.

1984 U.S.A. Olympic Team

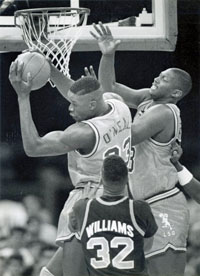

O'Neal recalls his freshman year at LSU (1989-90).

And I guess you could say I cared too much.

I wanted to be good. I liked the way it felt when I put up numbers and people slapped me on the back and gave me high fives. It was great with the ladies, too. Everybody loved the basketball players on campus. I was only seventeen years old when I showed up at LSU, but I was almost seven feet tall and ready to start my fabulous new life. ...

The time I spent at LSU was the best three years of my life. Dale Brown was an excellent coach and an even better person. He's one of my best friends in the world. He stuck up for me a hundred different times.

One of the things I liked about Coach Brown was he never promised me anything. When I got to campus he said, "If you work hard, anything can happen, but we've got this other guy named Stanley Roberts who is pretty doggone good."

Stanley. There he was again. That damn guy.

But here's the problem. I really liked Stanley. Everyone did. He was a cool dude. He wouldn't hurt anyone, except himself.

He was a Proposition 48 player, which meant his grades weren't quite good enough to play right away, so he had to sit out his first year and not play basketball. When I got to Baton Rouge, even though he had been there a year, it was his first basketball season.

Stanley had a 1979 Oldsmobile Toronado, and it was my job as the rookie freshman to drive him around. I'd take him to the clubs, wait for him outside, and mingle with the people going in and out. I loved it. I got to know so many people that way.

My freshman season in 1989-90, we were expected to do great things. We had Stanley and we had Chris Jackson, who had led the country in scoring the year before. Chris liked to shoot the ball. He could score from anywhere. We also had me, but nobody understood what that really meant yet.

Even though he had these two seven-footers to choose from, Chris still jacked it up about thirty times a game. Chris had Tourette's syndrome. It made him shout out random things for no apparent reason. It took some getting used to. I didn't really understand it. He needed to take some medication, and he hated it because sometimes it made him sick. Chris was off on his own a lot, so I never really got to know him very well. ...

I was humbled my freshman year. I thought I was The Man. What I realized when I got to LSU was that everyone there was The Man. Everyone was on scholarship, so I had to go all the way back down to zero. I had so much to learn about the game of basketball. In one of our first intrasquad scrimmages, Stanley was scoring on me and I was trying to guard him, and Coach was yelling to me, "Shaq, three-quarter him!"

I had no idea what he was talking about, but I was too embarrassed to tell him that. So I came down and I dunked on Stanley thinking that was going to make it all okay. But Stanley rolled out and spun away from and Coach started yelling again. "Three-quarter him!" Finally I stopped and said, "Coach, I don't know what you mean."

Coach Brown was very patient with me, but he was on me right away about my free throws. ...

One day Coach Brown came up to me in practice and said, "You know what I'm going to do? I'm going to get you to shoot underhand. Rick Barry, who is in the Hall of Fame, was the best at it."

"Coach," I pleaded with him, "please don't do that. Please don't make me shoot that granny shot. It's embarrassing."

I really didn't want to shoot them that way. When I was a kid, someone else suggested that approach before and Sarge told me to forget it. "That's a shot for sissies," my father told me.

Coach Brown said, "Okay, I'll tell you what I'm going to do. We're going to chart your free throws every day, separate from the team. You are going to be assigned a trainer, assistant coach, or manager with you at the basket every day. If you keep practicing and can shoot seventy percent or better, I'll let you keep taking them the way you are."

I shot 72 percent leading up to the season, but once I got in the games my percentage dropped to 56 percent. A lot of it was mental. If I was feeling good, I'd make them; if not, no chance. I could never get comfortable from the line, although I had a habit of making big free throws when it mattered. In our tournament game against Georgia Tech, for instance, I was 9 of 12 from the line. Why? I don't know.

I didn't start the first four games of the season, because, I think, Coach Brown was worried about people expecting too much. But once people saw me play, they said, "Okay, this kid is serious about being great."

What they meant was, I wasn't like Stanley.

Looking back, I realize in many ways Stanley made me who I am. It was good to have someone there who was better than me. He had it all - girls, money, cars. Everyone loved him. What got in his way was his partying. That day in the dungeon when I went after him with the trash can, Stanley was hungover. He was there trying to sweat out the alcohol. I'm thinking, Imagine how good he'd be if he hadn't been out all night.

I didn't drink, and after watching what it did to Stanley and some of the other guys, I was pretty sure I'd never be a drinker.

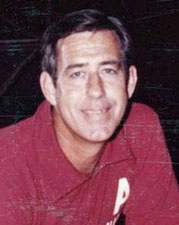

Understand that Fisher would not have gotten his magic night [winning the NCAA Tournament] in Seattle if his boss, Bill Frieder, hadn't been fired just before the tournament.

Frieder had been an eccentric and somewhat suspicious basketball coach at Michigan, who liked to write recruits as early as eighth grade. A jumpy guy by nature, Frieder was getting even jumpier with the new athletic director, Bo Schembechler - the football coaching legend - who would pound his fist and holler: "GOD DAMN IT! I WANT A SQUEAKY-CLEAN BASKETBALL PROGRAM. IS THAT UNDERSTOOD?"

Frieder understood. Bo didn't trust him. Although Frieder had never been found to have committed any violation, he liked to run a loose ship, let the kids be kids, let the boosters be boosters. He felt Bo's stare on the back on the back of his neck like a laser.

A job opened at Arizona State, sunshine, easier academic standards, great money, big fat contract. And no Bo. Frieder grabbed it.

Unfortunately he grabbed it two days before the start of the 1989 NCAA tournament, which, for many teams, is the only part of the season that really matters. Frieder flew to Phoenix, accepted the job, then telephoned back to Ann Arbor to inform Schembechler.

"Now, don't worry," Frieder told him, "I'm on my way back. I'll coach the team through the end of the tournament."

"The hell you will!" Schembechler snarled, the blood rising in his temples. "No Arizona State man is going to coach this team. A Michigan man will coach this team."

Exit Bill Frieder.

L-R: Bill Frieder, Bo Schembechler, Steve Fisher

Had Frieder stayed, Fisher probably would have left for a small Division I school somewhere, tried to build a program.

But now Schembechler was handing Steve Fisher the Michigan Wolverines, one of the premier college basketball teams in America.

Temporarily, of course.

"Here," Bo said, "coach the tournament. Do the best you can."

Well. In the first weekend, the Wolverines beat Xavier and eased past South Alabama. They came back the following weekend to outlast North Carolina and blow out Virginia. They came back a week later at the Final Four and stunned Illinois with a last-second basket, then beat Seton Hall in overtime on those Rumeal Robinson free throws.

And they cut down the nets.

National champions.

'MICHIGAN - KING OF THE COURT," read the cover of Sports Illustrated. The Wolverines were everybody's favorite underdog. They went to the White House, shook hands with the President. Fisher appeared on Good Morning America, ESPN, CBS. He was hailed as a breath of fresh air, an anathema to the joyless businessmen many college coaches had become.

After a brief waiting period, Schembechler did what most people expected: he gave Fisher the job full-time.

"You did a hell of a thing in that tournament, Steve," Bo told him. "You've earned the position. I'm raising your salary from $42,000 to $95,000. You'll have a shoe deal, a summer camp deal, and a TV and radio deal, which I will negotiate, if you like. The whole package should be worth between $300,000 and $400,000. That OK?"

OK? Was he kidding? The new head coach at Michigan? With six games on his resume? Fisher was dizzy. Nothing like this had ever happened to him before, and he tried to approach it with his typical steady, even-gazed approach. But that was like capping an oil well. Head? National champions? Six games?

President Bush invited Steve Fisher and Angie back to the White House. Fisher even phoned his alma mater, Illinois State - who had been interested in him as a coach - from the back of a Secret Service limo. "Sorry, I really appreciate the offer, but I'm going to take this little job here at Michigan ..." The back of a Secret Service limo?

Fisher got a six-figure shoe contract from Nike, and was invited to their annual party weekend in Newport Beach, California. Here he was strolling in the cool sunshine, chatting with Michael Jordan and Charles Barkley, getting the star treatment from hotshot Nike execs.

Back in Ann Arbor, Fisher got a nice car to drive, and he bought a beautiful house with his suddenly large income. People slapped his back, said, "Hi, coach."

What a life.

All he had to do was live up to his legend.

Juwan Howard was ranked the #4 high school senior in the 1991 recruiting class.

Jannie Mae Howard, the daughter of sharecroppers in Belzoni, Mississippi, had four babies by her nineteenth birthday, so she knew about motherhood, particularly young motherhood. When her teenage daughter Helena came home one night complaining about nausea, Jannie Mae sighed.

"It's that food down at the restaurant where I'm working, Mama," Helena said. "The smell of it makes me sick."

"It ain't the food, Helena. You're pregnant."

The doctors confirmed it. Helena quickly married the father, Leroy Watson, Jr., a phone company worker who had just come back from the army. And they lived for a while in the upstairs room at Jannie Mae's place on Chicago's South Side. But when Juwan was born, it was obvious the responsibility was too much for them. Helena was only 17, a junior in high school. When she brought the child home from the hospital, they didn't even have a crib for him. Jannie Mae told them to use the chest upstairs, open it up, get a pillow and a blanket, make sure it was sturdy.

For the first week of his life, Juwan Howard slept in a drawer.

Over the years, although his mother visited, Jannie Mae raised Juwan as her own. And he adored her. He sat by the kitchen table and watched her cook. He curled on the couch and fell asleep in her lap. She would tap her leg just enough to rock him to sleep, then light another cigarette and rub his head. She called him "Nookie," no one is sure why, but when she called, he listened.

"Nookie, go get me some cigarettes from Red's store."

"Aw, Grandma, I don't feel like -"

"What you say, boy?"

"Yes, Grandma."

They lived in several low-income projects, all on the South Side. At one point, they lived above a barbecue place, and they went to bed each night to the smell of the sauce. When Juwan came home one day with a homemade tattoo on his shoulder - "Dr. J." it read, after the basketball star - Jannie Mae let him have it, said he was too young to be scarring himself like that. And when the South Side gangs started calling, Jannie Mae locked the door, putting a sundown curfew on her grandson.

Jannie Mae Howard saved Juwan from an otherwise desperate street life, and she did it with love. For his grandma, Juwan went to school. For his grandma, he worked at his game. Jannie Mae was Juwan's guiding light. And if she liked a college, Juwan liked a college. Brian Dutcher [assistant coach at Michigan] knew this.

Not everyone was so smart. When Lute Olsen and the Arizona staff came to Chicago to recruit Juwan, they mistakenly thought he and his coach were the only important people in the room. They directed the conversation toward the men. Lannie Mae, feeling ignored, went out on the porch and smoked cigarettes until they finished. On their way out, Olson asked if she had any questions.

"What the hell you asking me now for?" she said, blowing a cloud of smoke. "You ain't asked me a damn thing the whole night." Their mouths fell. They were dead.

Jannie Mae wasn't Juwan's only influence, however. There was also a fast-talking, round-headed marketing major named Donnie Kirksey ... Kirksey had attached himself to Juwan early, joining the staff at Chicago Vocational High School, as an unpaid assistant coach, and befriending young Howard when he was a freshman. ... "You gotta be smart, Juwan," he would say. "You got a chance to get out of this neighborhood. You can't mess with no bad influences." ...

L-R: Brian Dutcher, Donnie Kirksey, Juwan Howard

One school, Kirksey claims, offered him $25,000 to get Juwan to commit and $10,000 for every month he stayed enrolled.

"He's not for sale," Donnie told them. And that was true: it was more like the barter system. Donnie hoped that steering Juwan to a major college coaching staff would help him achieve his own dream: getting on a major college coaching staff. Was he qualified? No. But stranger things had happened. ...

"Kirksey is really influential," Dutcher had warned Fisher. "We need to have him on our side."

So they recruited Kirksey as well. They phoned him. They encouraged his dreams of getting into the business. In the summer between Juwan's junior and senior years, Fisher actually hired Donnie Kirksey to work at his summer basketball camp in Ann Arbor, and paid him well. ...

The plan worked to perfection. Donnie was paid handsomely ... And Juwan had a great time in Ann Arbor, doing the camp, walking along the tree-lined campus, checking out the music stores and cafes, admiring the girls. This was a far cry from the noisy streets of South Chicago. ...

When Juwan took his "official" recruiting visit to Michigan in the fall of his senior year - his second actual stay - he was already quite fond of the maize and blue. On that same weekend, Fisher brought in Jimmy King, the star guard from Texas. He had the two of them stay together, go to the football game together, party on campus together. This was a smart move by Fisher. ...

And much to Fisher's pleasure, Juwan and Jimmy got along well, Juwan making jokes, Jimmy laughing and shrugging in his shy Texas way. They'd even talked about rooming together if both became Wolverines. ...

"Juwan, you know how much we want you here at Michigan," Fisher had told him at the end of his weekend. "You could have an immediate impact."

"Thanks, coach," Juwan said. "I'm pretty sure I'm coming. I'm supposed to take some other visits, but you guys are my first choice." ...

This was the day. November 14, 1991. Time for Juwan to make his announcement. His grandma woke him, as she always did. He'd never used an alarm clock. ...

"When I make the NBA one day," he told himself, looking in the mirror, "I'm gonna take care of Grandma. Buy a big house in the suburbs."

He came downstairs, gulped breakfast, kissed her goodbye.

"I love you, Grandma."

"Hmmm-mmm. Go on now."

He and Jannie Mae had signed the letter of intent this morning, so everything was legit. He felt good, he felt relieved. At school, he met with reporters and told them his decision.

"I think Michigan is a great school, and I'll be able to contribute to their program." ...

When he returned to 135th Street, the street lamps were on. He parked his car and saw several people outside his apartment, which was strange. He recognized one woman. Friend of the family's. She seemed upset. He rolled down the window.

"Oh, Juwan, I'm so sorry for you."

"What do you mean?"

"You don't know?"

She looked shocked. "I, um, I shouldn't be the one to tell you."

"Tell me what?"

"You should find out in ther-"

"Tell me what?"

The woman began to cry. "I'm sorry, Juwan. Your grandmother ... she ..."

Juwan shivered. A hurt began to rise from a part of his belly he never knew he had. It lifted him from the car and up the steps.

"Naw," he said, looking in. "NAW!" ...

Jamie Mae Howard had collapsed in the kitchen that afternoon while talking to her daughter about Juwan's future. A heart attack, they said, massive. She was dead by the time she reached the hospital.

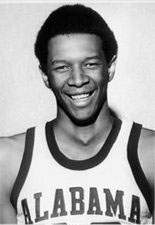

Black Players in the ACC and SEC, Barry Jacobs (2008)

For a quarter-century, until supplanted in 1968 by Coleman Coliseum, Foster Auditorium hosted Crimson Tide basketball games ... The brick and stone building ... seated 5,400. But while the "Rocket Eight" generated excitement en route an an SEC title during the pre-integration 1950s, basketball rarely attracted a full house. "Alabama never tried to have a basketball program," notes Clyde Bolton in The Basketball Tide.

That all changed with the arrival of head coach Charles "C. M." Newton and a flood of Alabama-born African Americans, starting with Birmingham's Wendell Hudson in 1969-70. The Tide made its first post-season appearance during Hudson's senior season. By then, four of Alabama's five starters were black. ...

The first attempt to integrate the University of Alabama, made in 1956, had ended after three days of demonstrations, a riot, and the expulsion of the applicant ..., ostensibly for her own safety. ...

Under the colonnade at the north entrance of Foster Auditorium, Alabama governor George Wallace made his televised "stand in the schoolhouse door" in June 1963, defying federal orders to integrate the state's flagship university. ...

Wallace ultimately stepped aside, acquiescing when a general from the federalized Alabama National Guard formally requested that he do so. ...

Laws changed and restrictions eased, but the image of Wallace's intransigence lingered. Certainly it came to mind when Mildred Hudson's only son told her in the spring of 1969 that he wished to attend the University of Alabama. "My mom was terrified," Wendell Hudson recalls. ... Although a smattering of black students had attended "the Capstone," as the university is called, none had been athletes.

"He broke the ice for the rest of them to go down there," Ms. Hudson says of her eldest child, a 6-foot-6 center who played at Birmingham's all-black Parker High School. "Somebody had to break it, but sometimes I wonder why it had to be him."

L: C. M. Newton; R: Wendell Hudson

Hudson's senior year in high school, the Parker Thundering Herd, boasting several college prospects, captured the 1969 state high school championship. That was the first season in which black and white Alabama teams competed for the same title. ...

The 1969 state tournament allowed Hudson to shine on the state's biggest prep stage. "I stepped in and did something that surprised even some of my teammates. ..." he remembers. Meanwhile, Newton, in his first year as Alabama's head basketball coach, endured a 4-20 season. The inauspicious debut was hardly reassuring for the little-known 38-year-old, who recalls being greeted at Tuscaloosa by a story headlined, "C. M. Who? Named 'Bama Coach." ...

At modest Transylvania College in Lexington, Kentucky, he had quietly integrated the basketball program as head coach...

It helped that Bryant, Alabama's football coach and athletics director and a legendary figure in the state, was supportive, for reasons of his own.

"What I wanted to do was build a basketball program at Alabama," says Newton, a member of the Basketball Hall of Fame. ..."The question I asked of Coach Bryant was, 'Are there any restrictions?' And his answer was, 'No, there are no restrictions. You've got to recruit legally and you've got to recruit guys that can finish school here ... So, [race] was not an issue."

For his part, Bryant said he hired Newton, a calm pipe smoker rarely given to profanity, "because he's the only basketball coach I know who isn't crazy." ...

Given Bryant's blessing, Newton made history at Alabama by signing Hudson, the school's first African-American scholarship athlete in any sport ... The Birmingham News touted the signing in its April 2, 1969, "Dixie Edition," but widespread attention was fleeting. Hudson was not considered a major prospect, and this was only basketball, after all, in a state where football is "a way of life," as Bryant said.

"I've been asked, 'Why did you go to the University of Alabama?'" says Hudson, whose other scholarship offers came mostly from small schools. ... "I never felt like I was inferior. ..."

As Bryant anticipated, the school's first black athlete encountered difficulties on the road. There also was resentment in Birmingham's black community because Hudson had chosen to attend a white school. For the most part, though, the fearsome antagonisms championed by George Wallace ... blew quietly past. ...

Hudson says, "I don't have the horror stories. I played for the right people. I probably went to what everybody thought was the worst place, after what all transpired there. But once Coach Bryant said everything was OK, everything was OK. ..."

Hudson went on to an outstanding collegiate career. He set a freshman record at Alabama for rebounding, then recovered from a broken wrist his sophomore year to earn consecutive berths on the all-conference squad as an upperclassmen. He was named SEC Player of the Year as a senior, the first black athlete so honored. ... His senior year the Crimson Tide reached the National Invitation Tournament, its first postseason appearance in 61 years of playing basketball.

Of the 11 Alabama players who took to the NIT court at New York's Madison Square Garden that year, 9 were black. Hudson's signing had done for the University of Alabama what Perry Wallace's did for the SEC: opened a floodgate through which poured talented, homegrown African-American players. ...

Remarkably, within a decade of George Wallace's stand in the schoolhouse door, Newton had built a successful program ... so heavily reliant on black players that some accused the coach of discriminating against whites.

"Looking back, the key to the whole thing at Alabama was Wendell," Newton says ... "I've gotten a lot of credit over the years for integrating the Alabama program and the SEC. I've even been called courageous. But it didn't take any courage on my part. However, it took tremendous courage on Wendell's part."