Origin of Basketball

24 Seconds to Shoot, Leonard Koppett (1968)

All other popular games - baseball, football, hockey, tennis, boxing, wrestling, fencing, and all the various types of races and field events - evolved gradually, through generations of informal practice. The final, familiar rules were distilled from countless trial-and-error experiments, long after the popularity of the activity had proved itself.

Basketball, on the other hand, was invented from scratch by James Naismith in 1891 in Springfield MA. He had a very specific, and limited, purpose: to provide an athletic activity, more enjoyable than calisthenics, that could be engaged in during the winter months, indoors, when it was not possible (in New England) to play baseball or football ...

Naismith's needs were specific, too. He was an instructor in physical education, attending the International Young Men's Christian Association Training School at Springfield MA. His orientation was towards physical fitness. The competitive side of athletics was, for him, a stimulant that made exercise more pleasurable and attractive, not an end in itself - and certainly not the raw material for entertaining spectators. His ideals were those of the participant and the amateur,and his search was for an indoor game that groups of men could play with a great deal of exertion in a small place.

So, in his little gymnasium which had a running track circling the floor like a balcony, he hung two peach baskets, one at each end; he got a soccer ball; and he divided his class (18 men) into two teams. The idea was to throw the ball into the basket. The rules of play were almost automatically determined by the conditions. Purposeful blocking and tackling couldn't be allowed on a wooden floor, and would make progress impossible anyhow; but unopposed running with the ball in such a small space would make the offense unstoppable.

L-R: James Naismith, YMCA basketball team c. 1900

Therefore, the ball had to be either bounced (dribbled) or passed to another player; and defenders had to devise ways of "guarding" that still permitted the offensive player enough freedom to throw the ball to a teammate or at the basket. Thus, the basic characteristics of the game - that undue interference by the defense was a "foul," and that artificial means (dribbling or passing) had to be used to advance the ball - were built in from the start.

The problems were built in from the start, too: exactly how much body-contact constituted a foul? When did a legal dribble slip over into "traveling"? When was the offensive player responsible for contact and a foul, and when the defensive player? These intrinsically borderline judgments, always affected by angle o vision and the subjective reaction of the observer, put a tremendous burden on the referee. His decisions, inevitably had a greater effect on the outcome than in other games, and this feature of basketball has never been overcome with complete satisfaction.

However, as an exercise activity, with not too much attention to the score, it proved to be ideal, and an immediate hit with the participants. Within three years it had been introduced from coast to coast, by graduates of the Springfield classes and by active letter writing. Many who tried it immediately became addicts, and rules were quickly put into stable and standardized form.

By 1895, various YMCA teams were holding regional tournaments, and basketball players were taking the game into high schools and colleges. To the participants, the sugar-coating had become the main course.

And it was this instant popularity that generated serious difficulties. Naismith had done far more than he had imagined. The game was so fascinating that its competitive aspects could not be kept under control. The good athletes who tried it became, like all good athletes, intent on winning, and tournaments added to the incentive. With victory prized so highly, the game became rough, since there were few experienced referees and no effective ruling body. It became too rough to be looked upon, by YMCA administrators, as healthful exercise; nor could the presence of an increasing number of spectators, reacting passionately to their rooting interests, be fitted in to the YMCA program. ...

The YMCA, therefore, embarked on a campaign of de-emphasis, only a few years after popularizing the sport it had invented. It discouraged the formation of club teams, and the conducting of tournaments.

Basketball, on the other hand, was invented from scratch by James Naismith in 1891 in Springfield MA. He had a very specific, and limited, purpose: to provide an athletic activity, more enjoyable than calisthenics, that could be engaged in during the winter months, indoors, when it was not possible (in New England) to play baseball or football ...

Naismith's needs were specific, too. He was an instructor in physical education, attending the International Young Men's Christian Association Training School at Springfield MA. His orientation was towards physical fitness. The competitive side of athletics was, for him, a stimulant that made exercise more pleasurable and attractive, not an end in itself - and certainly not the raw material for entertaining spectators. His ideals were those of the participant and the amateur,and his search was for an indoor game that groups of men could play with a great deal of exertion in a small place.

So, in his little gymnasium which had a running track circling the floor like a balcony, he hung two peach baskets, one at each end; he got a soccer ball; and he divided his class (18 men) into two teams. The idea was to throw the ball into the basket. The rules of play were almost automatically determined by the conditions. Purposeful blocking and tackling couldn't be allowed on a wooden floor, and would make progress impossible anyhow; but unopposed running with the ball in such a small space would make the offense unstoppable.

L-R: James Naismith, YMCA basketball team c. 1900

The problems were built in from the start, too: exactly how much body-contact constituted a foul? When did a legal dribble slip over into "traveling"? When was the offensive player responsible for contact and a foul, and when the defensive player? These intrinsically borderline judgments, always affected by angle o vision and the subjective reaction of the observer, put a tremendous burden on the referee. His decisions, inevitably had a greater effect on the outcome than in other games, and this feature of basketball has never been overcome with complete satisfaction.

However, as an exercise activity, with not too much attention to the score, it proved to be ideal, and an immediate hit with the participants. Within three years it had been introduced from coast to coast, by graduates of the Springfield classes and by active letter writing. Many who tried it immediately became addicts, and rules were quickly put into stable and standardized form.

By 1895, various YMCA teams were holding regional tournaments, and basketball players were taking the game into high schools and colleges. To the participants, the sugar-coating had become the main course.

And it was this instant popularity that generated serious difficulties. Naismith had done far more than he had imagined. The game was so fascinating that its competitive aspects could not be kept under control. The good athletes who tried it became, like all good athletes, intent on winning, and tournaments added to the incentive. With victory prized so highly, the game became rough, since there were few experienced referees and no effective ruling body. It became too rough to be looked upon, by YMCA administrators, as healthful exercise; nor could the presence of an increasing number of spectators, reacting passionately to their rooting interests, be fitted in to the YMCA program. ...

The YMCA, therefore, embarked on a campaign of de-emphasis, only a few years after popularizing the sport it had invented. It discouraged the formation of club teams, and the conducting of tournaments.

LSU Alumni Magazine, Spring 2019

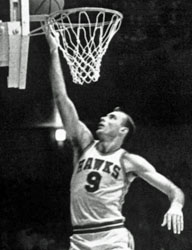

Bob Pettit may have played better games in his eleven All-Star seasons in the National Basketball Association - but not when there was so much riding on the outcome. His magical performance against the celebrated Celtics came with the world championship at stake.

Pettit scored 50 points, then a league playoff record, on that April night more than sixty years ago. The St. Louis Hawks needed his prolific effort to beat Boston in Game 6 for the 1958 NBA championship. It was especially satisfying for the Hawks. Red Auerbach's Celtics had edgedSt. Louis in Game 7 of the 1957 playoffs.

Pettit's offensive gem included a dramatic finish. He scored 19 of the Hawks final 21 points, and he made a goal with 15 seconds remaining for the 110-109 victory.

The former LSU All-America hit on 19 of 34 FG attempts, connected on 12 of 15 FTs, and led St. Louis with 19 rebounds. Only one other member of the Hawks - Cliff Hagan - was in double figures with 15 points.

Boston had five players in double figures led by Bill Sharman with 26, Tom Heinsohn with 23, and Bob Cousy with 15. But Pettit was a relentless scoring machine.

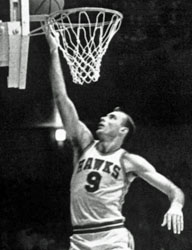

L-R: Bob Pettit in 1958, Bill Russell, Tom Heinsohn

That game was one of two basketball games that stand out in Pettit's memory.

The other game was the 1950 Louisiana high school state championship game in which Baton Rouge High defeated St. Aloysius of New Orleans. "You can't really compare the games," Pettit told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. "But at the time, winning the state title meant so much."

The Celtics began a remarkable winning sequence in 1957, edging St. Louis 125-123 in a legendary final that lasted two OTs. From 1957 through 1966, Boston won nine of 10 NBA championships. Pettit and the St. Louis Hawks could not be stopped in 1958. For years, Auerbach, the Celtics' coach, would needle Heinsohn about the 1958 Final - the one that got away. "We could have won 10 in a row if you had held Bob Pettit to 48 points."

With Pettit's scoring, rebounding, and leadership, St. Louis rivaled Boston in the NBA finals for four seasons - 1956-57, 1957-58, 1959-60, and 1960-61.

In the first game of the 1957 Finals at the Boston Garden, Pettit scored 37 points as the Hawks upset the Celtics and their emerging star Bill Russell in double OT. Pettit's shot won the third game at St. Louis. He sank two FTs with six seconds remaining in Game 7, forcing OT. However, his 39 points and 19 rebounds in 56 minutes of play were not enough to win in double OT of one of the most exciting games in NBA playoff history.

After Pettit's playing days had ended, Russell offered this tribute: "Bob made 'second effort' a part of the sports vocabulary. He kept coming at you more than any man in the game. He was always battling for position, fighting you off the boards."

Alex Hannum, who took over as the Hawks coach with 31 games left in the 1957 season, said Pettit's attitude was the reason for the club's success. "I was an old-timer when he was a rookie, and I saw him mature into a great player," Hannum told the Houston Chronicle. "He's a winner, whether it was in playing cards or the court. I always said it was no fun to play poker against Bob Pettit, because he always played to win, not just to have fun."

He is considered the great forward of his era.

Pettit scored 50 points, then a league playoff record, on that April night more than sixty years ago. The St. Louis Hawks needed his prolific effort to beat Boston in Game 6 for the 1958 NBA championship. It was especially satisfying for the Hawks. Red Auerbach's Celtics had edgedSt. Louis in Game 7 of the 1957 playoffs.

Pettit's offensive gem included a dramatic finish. He scored 19 of the Hawks final 21 points, and he made a goal with 15 seconds remaining for the 110-109 victory.

The former LSU All-America hit on 19 of 34 FG attempts, connected on 12 of 15 FTs, and led St. Louis with 19 rebounds. Only one other member of the Hawks - Cliff Hagan - was in double figures with 15 points.

Boston had five players in double figures led by Bill Sharman with 26, Tom Heinsohn with 23, and Bob Cousy with 15. But Pettit was a relentless scoring machine.

L-R: Bob Pettit in 1958, Bill Russell, Tom Heinsohn

The Celtics began a remarkable winning sequence in 1957, edging St. Louis 125-123 in a legendary final that lasted two OTs. From 1957 through 1966, Boston won nine of 10 NBA championships. Pettit and the St. Louis Hawks could not be stopped in 1958. For years, Auerbach, the Celtics' coach, would needle Heinsohn about the 1958 Final - the one that got away. "We could have won 10 in a row if you had held Bob Pettit to 48 points."

With Pettit's scoring, rebounding, and leadership, St. Louis rivaled Boston in the NBA finals for four seasons - 1956-57, 1957-58, 1959-60, and 1960-61.

In the first game of the 1957 Finals at the Boston Garden, Pettit scored 37 points as the Hawks upset the Celtics and their emerging star Bill Russell in double OT. Pettit's shot won the third game at St. Louis. He sank two FTs with six seconds remaining in Game 7, forcing OT. However, his 39 points and 19 rebounds in 56 minutes of play were not enough to win in double OT of one of the most exciting games in NBA playoff history.

After Pettit's playing days had ended, Russell offered this tribute: "Bob made 'second effort' a part of the sports vocabulary. He kept coming at you more than any man in the game. He was always battling for position, fighting you off the boards."

Alex Hannum, who took over as the Hawks coach with 31 games left in the 1957 season, said Pettit's attitude was the reason for the club's success. "I was an old-timer when he was a rookie, and I saw him mature into a great player," Hannum told the Houston Chronicle. "He's a winner, whether it was in playing cards or the court. I always said it was no fun to play poker against Bob Pettit, because he always played to win, not just to have fun."

He is considered the great forward of his era.

- Pettit was an immediate hit, winning Rookie of the Year honors in 1955.

- He was an All-Star in each of his 11 seasons, an All-NBA First Team selection 10 times, and an All-NBA Secon Team pick once.

- He never finished below seventh in the NBA scoring race. He left the sport with two MVP Awards and an NBA championship ring.

- He, along with Wilt Chamberlain and Jerry Lucas, are the only three players who averaged more than 20 points and 20 rebounds in an NBA season.

- His 12,849 rebounds were second most in league history at the time he retired.

- His 16.2 rebounds per game average remains third in all-time NBA standings only to Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell.

- He was the first NBA player ever to reach the 20,000-point mark.

- No other retired player in NBA history other than Pettit and Alex Groza (who played only two seasons) has averaged more than 20 points per game in every season they've played. (Note: Michael Jordan averaged exactly 20 points per game in his final season.)

- Pettit was selected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1970 and named to the NBA 50th Anniversary All-Time Team in 1996.

After retiring from pro basketball at 32, this LSU graduate put his business degree to work. Pettit worked in the banking industry in Baton Rouge and Metairie for 23 years before becoming financial consultant in 1988. He was inducted into the LSU Alumni Association Hall of Distinction in 1989. He retired from Equities Capital Invesotrs, the company that he co-founded, in 2006.

Loose Balls: The Short, Wild Life of the American Basketball Association as Told by the Players, Coaches, and Movers and Shakes Who Made It Happen, Terry Pluto (1990)

|

|

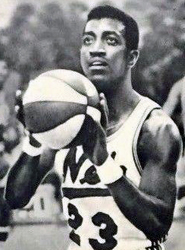

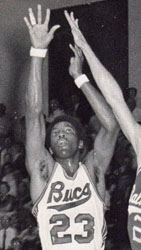

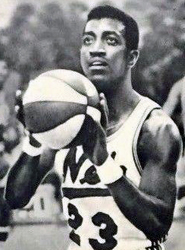

Steve Jones: I remember walking into a tryout for the Oakland Oaks at St. Mary's College and there were 100 guys there. I had some friends who had recommended me to the Oakland owners and Bruce Hale, so I had an advantage in that Bruce knew who I was. You could tell that there was a division at the camp between guys who were supposed to be able to play and guys basically off the street. I had played at Oregon and been drafted by the Warriors and had been to two of their training camps, so I was one of the guys who could play. But I still couldn't believe that mass of humanity in the gym. The coaches seemed overwhelmed. They started having 3-on-3 games for 15 minutes. If you didn't show much in that 15 minutes, you were outta there, so you can imagine that there was a lot of passing going on, right? They cut 60 guys the first day. I think back on that as the "Hundred Rifles" camp, because you had 100 guys doing nothing but shooting. Most of the guys who eventually made the team had played either in AAU ball or the Eastern League and had at least been to an NBA camp. ...

Bob Bass: Obviously, you had to be a bit of a gambler to get involved with the ABA. I had coached great NAIA teams at Oklahoma Baptist. We were national champs in 1966, runners up in 1965 and 1967. I could have stayed there comfortably forever or gone on to another major-college coaching job. I had a good player in Al Tucker, and Bruce Hale came down to talk to me about Tucker. Bruce had just been hired by Oakland, and he asked me if I was interested in getting into the ABA. I told him that I had no idea, I really hadn't thought about it. We pretty much let it drop at that.Two days later, I got a call from Dennis Murphy, who was then the general manager in Denver. Murphy offered me $20,000 to coach the team, which was pretty good, since most of the players were making $8,000. I took it. ... I had no players. We put together a tryout camp at Pacific University. We had about 100 guys in the gym and it got real hot, so we opened the doors. But it was so smoggy outside that the smog rolled in and it got so bad that we had to call off practice, because we couldn't see. Besides, an open tryout like that wasn't going to do us much good, anyway. ... I took the NBA rosters from 1965 to '67 and looked for the names of guys no longer in the league. Then I tried to track them down, figuring if they were good enough at one time to play in the NBA, then they should be good enough for our league. Actually, none of us really knew what would be good enough, since there was nothing to compare it to. ... One of the guys we did find was Tommy Bowens, who was 6-foot-8 from Grambling. He was one of the mroe amazing leapers I had ever seen. He could dunk from two feet behind the foul line. I know no one believes me when I tell them Bowens did that, but I saw it in practice. He could dunk from much further out than Julius Erving. He could break the high-jump and long-jump records all at the same time. He was just a raw talent who really couldn't do much with the basketball, but how he could jump. Larry Brown: The guy I still kid Bob Bass about is Lefty Thomas. We (New Orleans Buccaneers) played Denver early in the season and they had this guy, Lefty Thomas. He went for 20 points against us, but he shot it every time he touched it. That wasn't that unusual, but Lefty was the first player I had ever seen who wore a ring on every finger. I still ask Bob if he has signed any more guys who wear 10 rings. Bob Bass: Thomas had 39 points for us in our opener, but he was totally out of control. I couldn't handle the guy. Every time he got the ball, he went left and then he shot it. He had played for the Harlem Clowns and some of those other teams that played against the Globetrotters. After a few weeks, I let him go and Anaheim picked him up, maybe because he had the 39 points against them. But he didn't last there. Max Williams: Our biggest job was to find players. I got a lot of letters and calls. One guy wrote me from the state penitentiary in Oklahoma. He said if he could produce a contract, they'd let him out to play ball for Dallas. I passed on that one. We had an open tryout and drew about 100 guys. That was just a zoo, people killing each other, but we didn't find anyone of significance. Terry Stembridge: I don't remember seeing any real playes at those tryouts; it was just a bunch of guys running around. The players we ended up with were guys that Max found. One of my favorites was Maurice "Toothpick" McHartley. He was a 6-foot-3 guard who came from the Wilmington Blue Bombers of the Eastern League. Maurice had to have a toothpick in the corner of his mouth or he wouldn't play. He was ahead of everybody when it came to fashion, because he was the first guy on the team wearing bell-bottoms and stuff like that. He worked hard at being Mr. Cool. I remember him shooting the ball a lot, but I don't remember it going in that often. Another one of my favorite guys was A.W. Holt, a kid from Jackson State, a left-handed shooter. He went into Max's office to sign a contract and they talked for a while. When they came out, Max asked me to take Holt to the airport because he was going home. In the car, I said, "A.W., did you sign?" He said, "No, man, I didn't sign that contract." I said, "Why not?" He said, "I made up my mind before I came here that unless I got a $1,000 bonus, I wasn't going to sign. But all they offered me was fifteen hundred dollars." I started to laugh, but I realized that A.W. was serious. He didn't get it and that was sad. Anyway, he eventually did sign, but he didn't make the team. Larry Staverman: I was the first coach of the Indiana Pacers, and in the summer before that first season, we announced that we would have our first practice, which was really a tryout. We held it at the Jewish Community Center, which had room for about 400 people, but 1,500 showed up. We turned fans away to see a glorified tryout! ... Our big tryout was held at the Fairgrounds Coliseum. We had a couple of hundred guys trying out and about 7,000 fans there to watch. I stepped out on the court to start the tryout and guess what - no basketballs. My GM had forgotten to get us some balls. I had to figure out what to do with all these people. I had the guys run sprints, then I had them run a passing drill, a Figure-8, pretending they had a ball. I cut some guys before they even touched a ball because it was obvious they couldn't run and had no idea what the most basic Figure-8 drill was all about. |

Loose Balls: The Short, Wild Life of the American Basketball Association as Told by the Players, Coaches, and Movers and Shakers Who Made It Happen, Terry Pluto (1990)

The Floridians began life as the Minnesota Muskies, a franchise so well financed that after achieving a 50-28 record in the ABA's first season, it packed up and moved to Miami, where it put in four unremarkable years before mercifully folding at the end of the 1971-72 season. The Floridians never did much on the court, but the weather was nice and the ballgirls were nicer.

Rudy Martzke (Public Relations Man for the Floridians: Florida was a franchise with its own special lore. I don't know if it was the warm weather and people feeling like they could do anything they wanted, but there were a lot of crazy stories coming out of there, even by ABA standards. At one time, Florida had eight owners and one of the owners would go around saying, "Has Sidney dumped his 25 grand in yet? We going to make the payroll this week?" There really were stories in the newspaper saying, "The Floridians met the payroll so they'll play tonight."

One of the owners decided to trade for Art Heyman from Pittsburgh without telling anyone else. Heyman showed up in Miami without half the people in the front office knowing he was coming. Bob Halloran from TV-4 in Miami spotted Heyman and interviewed him.

Heyman asked Bob, "Does this go out to Miami Beach?"

Bob said it did.

Heyman said, "Hello, Jews out there! Your boy is here!"

On and on it goes.

L-R: Art Heyman, Levern Tart, Steve Jones

Levern Tart was from West Palm Beach, so they were going to have a Levern Tart Night, but the day before the game he got traded and it was to a team that didn't play in Florida again for the rest of the year.

They even played some games at a place in Coconut Grove where there were so many cockroaches in the dressing rooms that the visiting teams just changed at the hotel. I found out that being Miami's PR man was no bargain, especially since pro football owned the town. One Sunday afternoon, he had a home game scheduled against Utah while the Dolphins were playing Baltimore in the AFC playoffs at the Orange Bowl. By the time we realized that our game would go off at the same time as the Dolphins game, it was too late to change it. Not one press guy showed up for the game ... There were 500 people in the stands - maybe.

(Marketing Director) Kenny Small and I were talking and we decided to announce an attendance of 2,000. Who would know the difference? We settled on 1,650 which was still one of the bigger crowds of the season, and that was what ran under the box score. The next day we had press guys calling and saying, "Hey, that was a helluva crowd with the Dolphins playing and all." And I said, "Yeah, you should have been here."

Steve Jones: The walls in the dressing room were so thin and the two teams' rooms were next to each other, so everybody could hear everything. I was in there with New Orleans and we were up by about 20 points at the half. (Buccaneers coach) Babe McCarthy said, "Shush up, fellas. I want y'all to lissen ta what's going on next door." (Miami coach) Hal Blitman was going nuts, screaming and cussing everyone out. Babe was biting his lip to keep from laughing and we were doing the same thing - we didn't want them to hear us. As we walked out on the floor, all Babe said was, "That's what I'm gonna sound like after the game if we blow this one." Florida was the only place in the league where you could hear the other team's halftime talk.

Rudy Martzke (Public Relations Man for the Floridians: Florida was a franchise with its own special lore. I don't know if it was the warm weather and people feeling like they could do anything they wanted, but there were a lot of crazy stories coming out of there, even by ABA standards. At one time, Florida had eight owners and one of the owners would go around saying, "Has Sidney dumped his 25 grand in yet? We going to make the payroll this week?" There really were stories in the newspaper saying, "The Floridians met the payroll so they'll play tonight."

One of the owners decided to trade for Art Heyman from Pittsburgh without telling anyone else. Heyman showed up in Miami without half the people in the front office knowing he was coming. Bob Halloran from TV-4 in Miami spotted Heyman and interviewed him.

Heyman asked Bob, "Does this go out to Miami Beach?"

Bob said it did.

Heyman said, "Hello, Jews out there! Your boy is here!"

On and on it goes.

L-R: Art Heyman, Levern Tart, Steve Jones

They even played some games at a place in Coconut Grove where there were so many cockroaches in the dressing rooms that the visiting teams just changed at the hotel. I found out that being Miami's PR man was no bargain, especially since pro football owned the town. One Sunday afternoon, he had a home game scheduled against Utah while the Dolphins were playing Baltimore in the AFC playoffs at the Orange Bowl. By the time we realized that our game would go off at the same time as the Dolphins game, it was too late to change it. Not one press guy showed up for the game ... There were 500 people in the stands - maybe.

(Marketing Director) Kenny Small and I were talking and we decided to announce an attendance of 2,000. Who would know the difference? We settled on 1,650 which was still one of the bigger crowds of the season, and that was what ran under the box score. The next day we had press guys calling and saying, "Hey, that was a helluva crowd with the Dolphins playing and all." And I said, "Yeah, you should have been here."

Steve Jones: The walls in the dressing room were so thin and the two teams' rooms were next to each other, so everybody could hear everything. I was in there with New Orleans and we were up by about 20 points at the half. (Buccaneers coach) Babe McCarthy said, "Shush up, fellas. I want y'all to lissen ta what's going on next door." (Miami coach) Hal Blitman was going nuts, screaming and cussing everyone out. Babe was biting his lip to keep from laughing and we were doing the same thing - we didn't want them to hear us. As we walked out on the floor, all Babe said was, "That's what I'm gonna sound like after the game if we blow this one." Florida was the only place in the league where you could hear the other team's halftime talk.

|

Floridians' ball girl |

Gene Littles (long-time ABA G): No matter what you say about the Floridians, they had the greatest cheerleaders in the world. They were big league all the way, in their looks, their dance routines, and their outfits. They got more attention than the team and that was how it should have been considering the kind of teams they had down there. ... Martzke: The big event for the girls came when we took them to New York for a Madison Square Garden all-ABA doubleheader. It was right before Christmas. We had a press conference with the girls, got a big turnout and naturally pictures of the girls in the papers. ... Rick Barry was with the Nets and we had a promotion in Grand Central Station with Barry playing Al Albert in this gimmicky basketball game while the girls in their bikinis tried to lure people over to watch. It was pure schlock. The doubleheader drew about 8,500 at the Garden and about 8,000 of the fans showed up to see the girls, because I bet they couldn't name three guys who played that night. |

"We Got the Right Guy"

The Legends Club: Dean Smith, Mike Krzyzewski, Jim Valvano,

and an Epic College Basketball Rivalry, John Feinstein (2016)

and an Epic College Basketball Rivalry, John Feinstein (2016)

The night of December 5, 1980, was unseasonably warm in Greensboro, North Carolina. To most sports fans around the country, it was football season. The NFL was entering the final month of the regular season. College football teams were preparing for bowl games. In the state of North Carolina, though, it was already college basketball season. In a sense, it was always basketball season. ... Mickie Krzyzewski thought she understood that. She had been living in North Carolina for more than eight months, and just by reading the newspapers, she understood clearly that the job her husband had taken on the previous March was going to be a lot more pressurized than the one he had held for five years when he was the coach at Army. ...

There was only one place in the country where rivals like Duke and North Carolina might meet so early in the season, and that was in the Atlantic Coast Conference, specifically in North Carolina. Every season, long before conference play began, the four schools known collectively as the Big Four made the trip to Greensboro to play a two-night tournament ... It was one thing to play a quality opponent early in the season. It was quite another to play an opponent you would meet twice more during conference play and perhaps again in March, in the ACC Tournament. It was also very much another thing to play a game that brought your fans out in full voice when you were still trying to figure out what kind of team you might have. "I think the players enjoy it," Dean Smith often said. "I know the fans and the media enjoy it. It's us old coaches who aren't so thrilled about it." ...

Mickie Krzyzewski was accustomed to crowds of perhaps a thousand people coming to watch her husband’s team play in the old Army field house. There had been more people than that in the building during the first two games he had coached at Duke, but Cameron Indoor Stadium wasn't close to sold out, and the atmosphere had been somewhat louder than the school library, but hardly intimidating. Now though, as she walked into the Coliseum with Charles Huestis, one of Duke's vice presidents, it occurred to Mickie Krzyzewski that this was different from anything she had seen in the eleven years she and Mike had been married. "Toto, we're not in Kansas anymore," she murmured to herself ... She noticed all manner of people holding signs that said "Need Two" or "Need Four, Will Take Two." "They scalp tickets for this thing?" she asked Huestis, almost rhetorically. ...

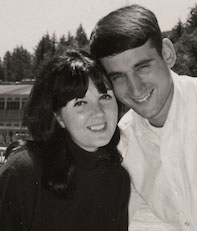

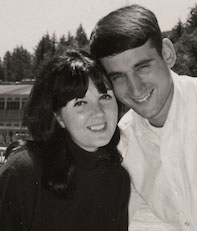

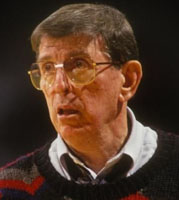

L-R: Mickie and Mike Krzyzewski, Dean Smith, Roy Williams

Duke had a good team, led by senior forwards Gene Banks and Kenny Dennard and junior guard Vince Taylor. North Carolina, as always, had a great team, keyed by future Hall of Famer James Worthy, senior All-American Al Wood, and freshman center Sam Perkins, who would go on to score more than 15,000 points in seventeen NBA seasons.

The game swayed back and forth to the very end. With time running down, Duke trailed 78–76 and had the ball. Banks missed a shot and the ball was deflected out-of-bounds—off a Tar Heel hand. Duke would inbound under the Carolina basket.

Except for one thing: the clock had run to zero during the skirmish for the ball underneath the basket. Krzyzewski instantly charged to the scorer's table, convinced there should be at least one second left on the clock to give his team a final chance to tie the game. There were no tenths of a second on the overhead scoreboard clock in those days, and there was no video replay available, so it was a very tough case to make.

As he continued to argue with the clock operator and the two referees, Krzyzewski saw Smith walking up to him, hand extended.

"Good game," he said.

Krzyzewski ignored the proffered hand. "The goddamn game's not over yet, Dean," he said.

But it was. The officials, having consulted with the clock operator, waved their arms to indicate the game was over and headed for the locker room. There was nothing left for Krzyzewski to do.

He turned to Smith and put out his hand.

Smith was never one for long postgame handshakes. In fact, before the days when teams started lining up to shake hands, he always ordered his assistant coaches and his players to head directly to the locker room when the buzzer went off—win or lose.

"It wasn't about sportsmanship," he said. "It was about avoiding trouble, especially at the end of a close game. A lot of times when we lost, teams would celebrate at midcourt. Tempers could be hot, and you didn’t want anything to happen if someone on one side said something to someone on the other side." The charge to the locker room was always led by Smith's top assistant, Bill Guthridge. ...

While Guthridge was leading everyone in light blue to the safety of the locker room, Smith would stay behind to shake hands with the opposing coach. The handshakes rarely lasted very long.

"Dean was usually a 'Good game' and gone guy," Krzyzewski said. “On that night, I didn’t let him do it."

In fact, when he finally turned to shake Smith's hand, Krzyzewski wouldn’t let it go. Smith, already more than a little annoyed by Krzyzewski's initial response, said nothing when they finally shook hands and started to pull away. Krzyzewski, a little younger and a little bigger, gripped his hand tightly and pulled Smith a few inches in his direction. "At least acknowledge that it was a hell of a game, Dean," he said.

Smith didn’t feel like acknowledging anything at that moment.

"I'm going to remember this," he answered.

"Good,” Krzyzewski said pointedly. "I hope you do."

The two men glared briefly at each other before parting.

A few feet away, Roy Williams witnessed the exchange. He was North Carolina's number-three assistant coach and, normally, would have been in the locker room. But, because of the potential issue with the clock, he had walked down behind Smith to deal with any questions—Should there be one second left if the game wasn't over? Two seconds? Where would Duke inbound from? Could Carolina substitute?—that might arise as a result of Krzyzewski's attempt to keep the game alive. As a result, he saw and heard everything that was said.

Many years later, he remembered the exchange quite vividly. "My first reaction was being kind of angry," he said. "I didn't like the idea that anyone would talk to Coach Smith like that. I have to say, though, looking at Mike at that moment, the thought went through my mind, 'There's no backdown in this guy.' I didn't like what I was hearing and seeing, but I respected it."

Sitting up in the stands, Steve Vacendak, Duke's associate athletic director, turned to his boss, Athletic Director Tom Butters, at the instant when he saw Krzyzewski refuse Smith's initial attempt at a handshake. "Tom," he said, "we got the right guy."

There was only one place in the country where rivals like Duke and North Carolina might meet so early in the season, and that was in the Atlantic Coast Conference, specifically in North Carolina. Every season, long before conference play began, the four schools known collectively as the Big Four made the trip to Greensboro to play a two-night tournament ... It was one thing to play a quality opponent early in the season. It was quite another to play an opponent you would meet twice more during conference play and perhaps again in March, in the ACC Tournament. It was also very much another thing to play a game that brought your fans out in full voice when you were still trying to figure out what kind of team you might have. "I think the players enjoy it," Dean Smith often said. "I know the fans and the media enjoy it. It's us old coaches who aren't so thrilled about it." ...

Mickie Krzyzewski was accustomed to crowds of perhaps a thousand people coming to watch her husband’s team play in the old Army field house. There had been more people than that in the building during the first two games he had coached at Duke, but Cameron Indoor Stadium wasn't close to sold out, and the atmosphere had been somewhat louder than the school library, but hardly intimidating. Now though, as she walked into the Coliseum with Charles Huestis, one of Duke's vice presidents, it occurred to Mickie Krzyzewski that this was different from anything she had seen in the eleven years she and Mike had been married. "Toto, we're not in Kansas anymore," she murmured to herself ... She noticed all manner of people holding signs that said "Need Two" or "Need Four, Will Take Two." "They scalp tickets for this thing?" she asked Huestis, almost rhetorically. ...

L-R: Mickie and Mike Krzyzewski, Dean Smith, Roy Williams

The game swayed back and forth to the very end. With time running down, Duke trailed 78–76 and had the ball. Banks missed a shot and the ball was deflected out-of-bounds—off a Tar Heel hand. Duke would inbound under the Carolina basket.

Except for one thing: the clock had run to zero during the skirmish for the ball underneath the basket. Krzyzewski instantly charged to the scorer's table, convinced there should be at least one second left on the clock to give his team a final chance to tie the game. There were no tenths of a second on the overhead scoreboard clock in those days, and there was no video replay available, so it was a very tough case to make.

As he continued to argue with the clock operator and the two referees, Krzyzewski saw Smith walking up to him, hand extended.

"Good game," he said.

Krzyzewski ignored the proffered hand. "The goddamn game's not over yet, Dean," he said.

But it was. The officials, having consulted with the clock operator, waved their arms to indicate the game was over and headed for the locker room. There was nothing left for Krzyzewski to do.

He turned to Smith and put out his hand.

Smith was never one for long postgame handshakes. In fact, before the days when teams started lining up to shake hands, he always ordered his assistant coaches and his players to head directly to the locker room when the buzzer went off—win or lose.

"It wasn't about sportsmanship," he said. "It was about avoiding trouble, especially at the end of a close game. A lot of times when we lost, teams would celebrate at midcourt. Tempers could be hot, and you didn’t want anything to happen if someone on one side said something to someone on the other side." The charge to the locker room was always led by Smith's top assistant, Bill Guthridge. ...

While Guthridge was leading everyone in light blue to the safety of the locker room, Smith would stay behind to shake hands with the opposing coach. The handshakes rarely lasted very long.

"Dean was usually a 'Good game' and gone guy," Krzyzewski said. “On that night, I didn’t let him do it."

In fact, when he finally turned to shake Smith's hand, Krzyzewski wouldn’t let it go. Smith, already more than a little annoyed by Krzyzewski's initial response, said nothing when they finally shook hands and started to pull away. Krzyzewski, a little younger and a little bigger, gripped his hand tightly and pulled Smith a few inches in his direction. "At least acknowledge that it was a hell of a game, Dean," he said.

Smith didn’t feel like acknowledging anything at that moment.

"I'm going to remember this," he answered.

"Good,” Krzyzewski said pointedly. "I hope you do."

The two men glared briefly at each other before parting.

A few feet away, Roy Williams witnessed the exchange. He was North Carolina's number-three assistant coach and, normally, would have been in the locker room. But, because of the potential issue with the clock, he had walked down behind Smith to deal with any questions—Should there be one second left if the game wasn't over? Two seconds? Where would Duke inbound from? Could Carolina substitute?—that might arise as a result of Krzyzewski's attempt to keep the game alive. As a result, he saw and heard everything that was said.

Many years later, he remembered the exchange quite vividly. "My first reaction was being kind of angry," he said. "I didn't like the idea that anyone would talk to Coach Smith like that. I have to say, though, looking at Mike at that moment, the thought went through my mind, 'There's no backdown in this guy.' I didn't like what I was hearing and seeing, but I respected it."

Sitting up in the stands, Steve Vacendak, Duke's associate athletic director, turned to his boss, Athletic Director Tom Butters, at the instant when he saw Krzyzewski refuse Smith's initial attempt at a handshake. "Tom," he said, "we got the right guy."

Memories of Wilt

West by West: My Charmed, Tormented Life, Jerry West (2011)

During my last year with the Lakers, the death of Wilt Chamberlain in October of 1999 hit me particularly hard. Wilt was only two years older than I was, and when I got word that he was dead, I didn’t believe it. In fact, it took nearly fifteen phone calls of my asking people "Is it true?" before I grudgingly accepted that it was. How could someone that strong and that athletic and that imposing be dead at the age of sixty-three? For as long as he played, Wilt was generally considered the greatest athlete in the world. He was also the most sensitive and insecure person I had ever been around. I thought I was sensitive and touchy, but Wilt took sensitivity to another level, constantly feeling unappreciated. As he always loved to say, "Nobody loves Goliath."

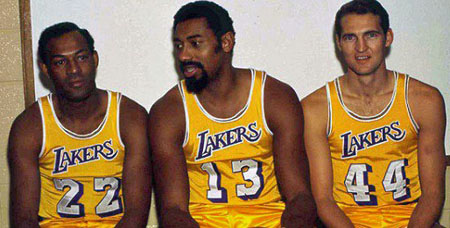

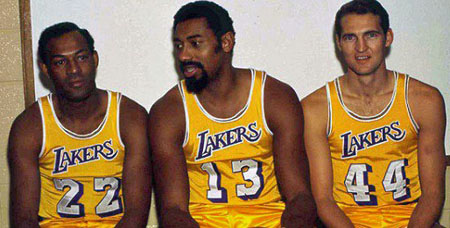

Elgin Baylor, Wilt Chamberlain, and Jerry West

I have been around a lot of big men in my life in professional basketball, but Wilt stood out as always being primed for an insult or a slight. He constantly complained that he would give parties at his hilltop home on Mulholland Drive and invite everyone—actually, he would have two parties in an evening: one for married couples and a much later party for singles—but that he often would go uninvited in return. In his book Wilt, he singled me out on more than one occasion as being one of the culprits, but I can promise you that Wilt ducked his head in the front door of my home in Brentwood, just off Sunset, on a number of occasions in the early seventies. He often expressed the opinion (as Oscar did) that the media loved me, that in their eyes I could do no wrong, but that he was seen as a villain.

I have so many memories of Wilt, and nearly all of them are funny ones. I remember during his beach volleyball period that he would arrive in his Rolls-Royce convertible at the Forum right before a game or practice with his light blue nylon shorts on and his flip-flops and sand in his hair. I never understood how he thought he would have enough energy to go out and play, but that was Wilt and he never felt he had to explain or justify anything (he could easily go for days without a real shower, blithely ignoring the deodorant and soap we would put in front of his locker, settling for a sponge bath instead). He of course insisted he was the greatest beach volleyball player of all time, but our teammate Keith Erickson, who actually played volleyball in the 1964 Olympics, said that while Wilt might have been the biggest and brightest star on the beaches of Santa Monica, he wasn’t a great player.

He was, however, a great eater. Perhaps the most vivid memory I have of Wilt is from Kansas City, when we were playing the Kings. I got a call from Wilt asking me to come up to his room, but he did not say why. Once I got there, I found him sitting like some sort of Buddha in those blue shorts, wearing nothing but a towel around his neck, and literally surrounded by food from Gates Bar-B-Q—slabs of ribs, pulled pork, one-pound brisket sandwiches, French fries, onion rings, collard greens, hush puppies, sauce, bread to soak it all up with—and two liters of 7-Up, his favorite drink. He wanted me to join him, and I was flattered, but since I knew that I couldn’t even get through half of one of those sandwiches, I politely said no. (But if I had joined him, my competitive spirit would have driven me to out-eat him, just as I "raced" Bill Russell to sleep—and won—when we flew back from the 2000 Olympics in Sydney.) That image of Wilt, alone in that hotel room, has never left me, and it is one of the reasons I think of him as perhaps the loneliest person I have ever known.

As for all Wilt's claims of having slept with twenty thousand women? That is such a joke, because he was with me a lot of the time. When his sister Barbara would stop in unannounced to see him, she would go searching for any sign that a female had been there, but she could never find anything, not an article of clothing, not a photograph, nothing. She even asked him about it. "Dippy," she said, “you say in your book that you slept with all these women, but you could have fooled me. I can’t find a thing."

When Bill Sharman became coach of the Lakers in 1971, he wanted to institute what he called the morning shootaround—he had the radical notion that he could persuade the team to actually practice on the day of a game. When Bill played for the Celtics, he found himself so restless on game day that he would go to a neighborhood school and shoot baskets in order to relax and stay sharp. He felt the key to getting the team to agree to this was Wilt, who often didn’t get out of bed until the afternoon. If Wilt could be convinced that it was a great idea, then it would happen. Bill was right, although Wilt made it clear that if the team started losing, he might have second thoughts. That was the year we won thirty-three games in a row, and the morning shootaround, much as the players dreaded it, became standard practice for all teams. Bill also felt it was important to ask Wilt if he wanted to be co-captain of the team, along with Elgin—that it would have great meaning for him—and asked my opinion. I told Bill that I thought it was a good idea, and it was, but I have often wondered why I was never captain of the Lakers before I retired.

Elgin Baylor, Wilt Chamberlain, and Jerry West

I have so many memories of Wilt, and nearly all of them are funny ones. I remember during his beach volleyball period that he would arrive in his Rolls-Royce convertible at the Forum right before a game or practice with his light blue nylon shorts on and his flip-flops and sand in his hair. I never understood how he thought he would have enough energy to go out and play, but that was Wilt and he never felt he had to explain or justify anything (he could easily go for days without a real shower, blithely ignoring the deodorant and soap we would put in front of his locker, settling for a sponge bath instead). He of course insisted he was the greatest beach volleyball player of all time, but our teammate Keith Erickson, who actually played volleyball in the 1964 Olympics, said that while Wilt might have been the biggest and brightest star on the beaches of Santa Monica, he wasn’t a great player.

He was, however, a great eater. Perhaps the most vivid memory I have of Wilt is from Kansas City, when we were playing the Kings. I got a call from Wilt asking me to come up to his room, but he did not say why. Once I got there, I found him sitting like some sort of Buddha in those blue shorts, wearing nothing but a towel around his neck, and literally surrounded by food from Gates Bar-B-Q—slabs of ribs, pulled pork, one-pound brisket sandwiches, French fries, onion rings, collard greens, hush puppies, sauce, bread to soak it all up with—and two liters of 7-Up, his favorite drink. He wanted me to join him, and I was flattered, but since I knew that I couldn’t even get through half of one of those sandwiches, I politely said no. (But if I had joined him, my competitive spirit would have driven me to out-eat him, just as I "raced" Bill Russell to sleep—and won—when we flew back from the 2000 Olympics in Sydney.) That image of Wilt, alone in that hotel room, has never left me, and it is one of the reasons I think of him as perhaps the loneliest person I have ever known.

As for all Wilt's claims of having slept with twenty thousand women? That is such a joke, because he was with me a lot of the time. When his sister Barbara would stop in unannounced to see him, she would go searching for any sign that a female had been there, but she could never find anything, not an article of clothing, not a photograph, nothing. She even asked him about it. "Dippy," she said, “you say in your book that you slept with all these women, but you could have fooled me. I can’t find a thing."

When Bill Sharman became coach of the Lakers in 1971, he wanted to institute what he called the morning shootaround—he had the radical notion that he could persuade the team to actually practice on the day of a game. When Bill played for the Celtics, he found himself so restless on game day that he would go to a neighborhood school and shoot baskets in order to relax and stay sharp. He felt the key to getting the team to agree to this was Wilt, who often didn’t get out of bed until the afternoon. If Wilt could be convinced that it was a great idea, then it would happen. Bill was right, although Wilt made it clear that if the team started losing, he might have second thoughts. That was the year we won thirty-three games in a row, and the morning shootaround, much as the players dreaded it, became standard practice for all teams. Bill also felt it was important to ask Wilt if he wanted to be co-captain of the team, along with Elgin—that it would have great meaning for him—and asked my opinion. I told Bill that I thought it was a good idea, and it was, but I have often wondered why I was never captain of the Lakers before I retired.

Tiger in a Lion's Den: Adventures in LSU Basketball, Dale Brown with Don Yaeger (1994)

|

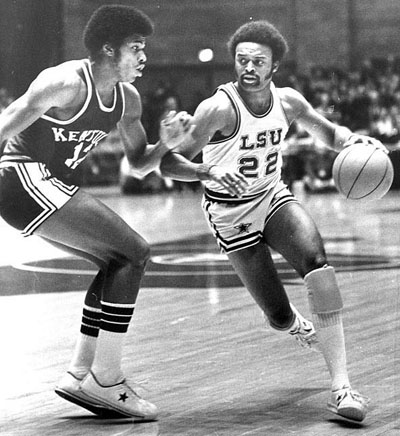

Though there was an abundance of seats available at the assembly center when we took over, that changed as we started turning things around. And while it felt then like it took forever to get things moving upwards, the truth is we started creating excitement in the first five years. My good friend Jim Talbot has told me that he and several of his friends really thought about coming out to see us after a game we played in Kentucky in 1976. It was a game we lost, but the stories that grew out of it drew a lot of attention. When we played against Kentucky we never got a break. This particular game is a perfect example of what it was like. LSU had never beaten Kentucky at Rupp Arena, but we were leading and it looked like we had a real good chance of breaking that string. One of our best players, Kenny Higgs, was from Kentucky. He was runner up for Mister Basketball in Kentucky. Anyway, Kenny was headed for a breakaway layup and a Kentucky player tackled him. It was clearly an intentional foul. I mean a fight almost broke out. The referees were trying to figure what to call. Is it intentional? Who gets kicked out? How many free throws does Higgs get? Does the basket count?  Kenny Higgs guarded by Larry Johnson in 1976 game in Baton Rouge As I walked back toward our bench, I could not believe just because Joe has a big name and I have no name, the referee was afraid of him but not me. Boy, I was not going to let this happen. So I headed back there again and he told me to sit down again. I told the referee, "I'm not gonna sit down." To make a long story short, I got the technical and then they fouled practically our whole team out by the end of the game. I had no one left to put in the game. There was two and a half minutes to go. I had my last man in there and by that time it was obvious we were going to lose. Joe still had his first team in. I said to myself, "You know what's happening here? It's the same thing that happened to my mother. She was in a bad spot, yet she shouldn't speak up. She had to take that welfare worker's stuff, she had to take that hard time from the landlady. I am not taking this." So I called timeout and walked over to the referee as calmly as I could. I took my coat off and I tapped him on the shoulder. I wasn't trying to get a technical, but I said, "Hey, I just want you to look over on my bench. We had a 12-point lead when this whole thing fell apart. I want you to look at my guys over there heartbroken." He just rolled his eyes and said, "What about it, Coach?" He was trying to be kind of smart. I told my assistant to take the huddle and I went back to the referee and said, "What about it? It's very simple. You've broken their hearts because this game has totally gotten out of hand. You and I both know that's not fair." I took off my coat and I said, "You've taken everything away from us. I've had all my starters foul out. I've got no one left to put in the game, so you might as well have a part of my wardrobe too. Here, take my sports coat." He looked at me like I was crazy and he said, "Oh no, I am not taking." I said, "No, please take it. You've got everything else." He turned his back on me so I thought I should make an impression on this guy. He's going to remember this, and maybe the next time he'll give us a break. "Well, if you won't take my coat, I'll tell you what I'm going to do. I'm taking it and I'm throwing it out right in the middle of that court." He waved his hand at me and said just go sit down. When he said "go sit down" like I was a junior high coach, I took off toward center court where Kentucky had a great big blue letter K painted right in the middle. I took off my sports coat and spun in around on my finger like a propeller and let it fly. It twirled around in the air and then floated down just perfectly on top of that K, completely covering it up. The Kentucky fans went nuts. Back home, people like Jim Talbot heard about it and decided they had better come out and get a look at this team. I really felt it was what I had to do at the time. Pretend you are a referee. Dale Brown comes in the league. Who is Dale Brown? He is just a guy from North Dakota. The weak referees were not ever going to give me a break, and there were some very very very weak officials in this league at one time.  Dale Brown tosses his sport coat at Kentucky. |

The Legends Club: Dean Smith, Mike Krzyzewski, Jim Valvano,

and an Epic College Basketball Rivalry, John Feinstein (2016)

and an Epic College Basketball Rivalry, John Feinstein (2016)

From the Introduction

In a very real sense, this book was born on February 28, 1976—Dean Smith’s forty-fifth birthday. It was on that afternoon that a very nervous reporter from Duke’s student newspaper, The Chronicle, timidly introduced himself to the great man in a corner of the North Carolina locker room in Carmichael Auditorium. North Carolina had just finished beating Duke, 91–71, dropping Duke’s record to 13–13. The outcome wasn’t a surprise. Carolina was ranked fourth in the country and had run away with the ACC regular season title, finishing 11–1. The Tar Heels were 24–2 and had four players on their roster who would be on the U.S. Olympic team—coached by Dean Smith —that summer: Mitch Kupchak, Walter Davis, Tommy LaGarde, and the great Phil Ford. Duke had Tate Armstrong. Who was my excuse to talk to Dean Smith. Armstrong had been lighting up ACC gyms all winter, a one-man show on a struggling team. Duke coach Bill Foster was in his second season, trying to rebuild the fallen Duke program. Armstrong had just finished his freshman season when Foster arrived and was now a junior. Armstrong did have some help from a superb freshman named Jim Spanarkel, but the Blue Devils were overmatched in the ACC—as their 3–9 conference record proved. For the season, Armstrong was averaging 24.2 points per game—making an astounding 52 percent of his shots. That was with no three-point shot and no shot clock, and with other teams gearing their defenses to stop him. He was a slender six foot two and spent as much time on the floor after being knocked down as he did in his shooting motion. He had scored 29 points that day against Carolina. I was going to write a column making the case that if ever a player from a team that finished seventh in a seven-team conference deserved consideration for player of the year, it was Armstrong. I might have been just a tad biased.

L-R: Dean Smith, John Feinstein, Tate Armstrong

Smith was talking to another writer when I walked up. When he finished the conversation he’d been having, he looked at me as if to say, “And?” Finding my voice somewhere, I said, “Coach Smith, my name is John Feinstein and I work for The Chronicle, the Duke student newspaper…” I had my hand out as I spoke and Smith shook it, stopping me before I could go further by saying, “I know who you are. I read the column you wrote last month saying that Bill [Foster] should copy some of what we do here to rebuild over at Duke. I thought you were very fair to us…for someone from Duke.” I had been more than fair. I had been gushy. But that wasn’t the point. I was standing in front of Dean Smith and he was telling me he had read something I had written. I was, to put it mildly, stunned. As I’ve written often in the past, it was later that I learned that the North Carolina basketball office subscribed to every newspaper in North Carolina—the major national papers and all the student newspapers in the ACC. An assistant coach was assigned to comb through the papers and clip anything relevant to Carolina for Smith to read. He would put the clips in his briefcase and read them on airplanes. Still stunned, I somehow got my question out about Armstrong. I’m not sure he ever answered it. Instead, he talked about how proud he was of Ford and Davis, but especially John Kuester, for the defensive job they’d done that day on Armstrong—even if he had scored almost half of Duke’s points. Somewhere in the middle of the answer he asked me where I’d grown up. I said New York. “City?” he asked. I nodded. “Well,” he said, “I guess that explains why you understand basketball.” Do you think he completely owned me at that moment? I asked one more question. Early in the game, when it was still close, a couple of calls had gone against Carolina. Some of the students had started a profane chant. It didn’t last very long, because Smith walked straight to the scorer’s table, took the PA microphone, pointed in the direction of the students, and said, “Stop. Now. We don’t do that here. We win with class at Carolina.” They stopped. Instantly. When I asked about the incident, he smiled again. “I was disappointed that happened,” he said. “It won’t happen here again.” Then he added, “We’re not Duke.” And, at that moment, Duke was miles and miles from being North Carolina.

In a very real sense, this book was born on February 28, 1976—Dean Smith’s forty-fifth birthday. It was on that afternoon that a very nervous reporter from Duke’s student newspaper, The Chronicle, timidly introduced himself to the great man in a corner of the North Carolina locker room in Carmichael Auditorium. North Carolina had just finished beating Duke, 91–71, dropping Duke’s record to 13–13. The outcome wasn’t a surprise. Carolina was ranked fourth in the country and had run away with the ACC regular season title, finishing 11–1. The Tar Heels were 24–2 and had four players on their roster who would be on the U.S. Olympic team—coached by Dean Smith —that summer: Mitch Kupchak, Walter Davis, Tommy LaGarde, and the great Phil Ford. Duke had Tate Armstrong. Who was my excuse to talk to Dean Smith. Armstrong had been lighting up ACC gyms all winter, a one-man show on a struggling team. Duke coach Bill Foster was in his second season, trying to rebuild the fallen Duke program. Armstrong had just finished his freshman season when Foster arrived and was now a junior. Armstrong did have some help from a superb freshman named Jim Spanarkel, but the Blue Devils were overmatched in the ACC—as their 3–9 conference record proved. For the season, Armstrong was averaging 24.2 points per game—making an astounding 52 percent of his shots. That was with no three-point shot and no shot clock, and with other teams gearing their defenses to stop him. He was a slender six foot two and spent as much time on the floor after being knocked down as he did in his shooting motion. He had scored 29 points that day against Carolina. I was going to write a column making the case that if ever a player from a team that finished seventh in a seven-team conference deserved consideration for player of the year, it was Armstrong. I might have been just a tad biased.

L-R: Dean Smith, John Feinstein, Tate Armstrong

How old is your son?

Hard Work: A Life on and off the Court, Roy Williams (2009)

1989-90 was Roy's second season as head coach at Kansas.

1989-90 was Roy's second season as head coach at Kansas.

We started that season against Alabama-Birmingham in the Preseason NIT at our place. Kevin Pritchard scored 22 points and we beat them by 26. At 6:30 the next morning I got a call from our assistant athletic director, who said, "At first, it looked like we were going to play the next round at DePaul, but they changed their minds. Now we're going to play at LSU."

I said, "What's going on?"

"Well, UNLV is No. 1 and LSU is No. 2, and they want to make sure they both get to the semifinals in New York City. They'd also like to see DePaul and St. John's get there, so they're sacrificing us."

So we flew down to play LSU and they had Shaquille O'Neal and Stanley Roberts, who was just as big as Shaq, and a great guard, Chris Jackson ... I added it up later and their starting lineup's first-year pro contracts combined to be $16 million. We had one pro who made $180,000. But I still thought we had a great chance to win. We got to the gym, and Dick Vitale showed up to watch us practice. Dick said, "Well, they're really giving you a tough road because they want LSU and UNLV in New York."

I said, "Dick, we're going to spoil the party."

"What are you talking about?"

"We're going to beat 'em." Then I called my team over to where Dick and I were talking. I said, "I just told Mr. Vitale here that we're going to spoil the party, we're going to win this frickin' game. They want LSU in Madison Square Garden, and we're not going to let that happen."

I let the team go back to finishing shootaround, and Dick said, "Now I know you're just a second-year coach. Do you really feel good about saying that?"

"Yeah, Dick, we're going to beat 'em."

So then we walked off the court, and (assistant coach) Jerry Green said to me, "You're damn crazy."

L-R: Roy Williams, Kevin Pritchard, Shaquille O'Neal

We went back to the hotel and that night at snack I said to the team, "Guys, I want you to go to bed and think about who you're going to hug first at the end of this game, because we're going to win this frickin' game. We're going to move, we're going to pass, we're going to make Shaquille O'Neal and Stanley Roberts spin around so much they'll wear a hole in the floor." The players left and Jerry Green said, "You're damn crazy."

The next night we were spreading the floor and moving and cutting and slashing around so quickly that their big guys couldn't keep up with us; we played great and won the game. Everybody was running around hugging afterward. It was one of those really satisfying moments. The next day while we were at the hotel packing up the bus for the airport, this guy came over to me and said, "Coach, that was some kind of job last night."

"Well, thank you," I said. "Our guys really played well."

"The way you moved the ball, and the way your big guys posted up, I wish I could get my son to play like that."

"Well, thanks again. We were really good. How old is your son?"

"I'm Shaq's daddy."

Beating No. 2 LSU earned us a trip to New York City to face No. 1 University of Nevada-Las Vegas. I went to Tavern on the Green for a press conference and they introduced me as Ron Williams. I stood up and said, "Folks, that doesn't bother me, because we are going to play our butts off and by the end of this tournament, you're going to know my first name."

UNLV had stars like Larry Johnson and Stacey Augmon and Greg Anthony and Anderson Hunt, all of whom would go on to play in the NBA. But I thought we could neutralize their pressure defense with backdoor cuts. We played almost a Princeton-style offense and they never figured us out. At one point in the second half we were up by 20 points and we ended up winning by 15. Their coach, Jerry Tarkanian, said afterward that he'd never had one of his teams handled like that.

L-R: Malik Sealy, Terry Brown, Lou Carnesecca

I said, "What's going on?"

"Well, UNLV is No. 1 and LSU is No. 2, and they want to make sure they both get to the semifinals in New York City. They'd also like to see DePaul and St. John's get there, so they're sacrificing us."

So we flew down to play LSU and they had Shaquille O'Neal and Stanley Roberts, who was just as big as Shaq, and a great guard, Chris Jackson ... I added it up later and their starting lineup's first-year pro contracts combined to be $16 million. We had one pro who made $180,000. But I still thought we had a great chance to win. We got to the gym, and Dick Vitale showed up to watch us practice. Dick said, "Well, they're really giving you a tough road because they want LSU and UNLV in New York."

I said, "Dick, we're going to spoil the party."

"What are you talking about?"

"We're going to beat 'em." Then I called my team over to where Dick and I were talking. I said, "I just told Mr. Vitale here that we're going to spoil the party, we're going to win this frickin' game. They want LSU in Madison Square Garden, and we're not going to let that happen."

I let the team go back to finishing shootaround, and Dick said, "Now I know you're just a second-year coach. Do you really feel good about saying that?"

"Yeah, Dick, we're going to beat 'em."

So then we walked off the court, and (assistant coach) Jerry Green said to me, "You're damn crazy."

L-R: Roy Williams, Kevin Pritchard, Shaquille O'Neal

The next night we were spreading the floor and moving and cutting and slashing around so quickly that their big guys couldn't keep up with us; we played great and won the game. Everybody was running around hugging afterward. It was one of those really satisfying moments. The next day while we were at the hotel packing up the bus for the airport, this guy came over to me and said, "Coach, that was some kind of job last night."

"Well, thank you," I said. "Our guys really played well."

"The way you moved the ball, and the way your big guys posted up, I wish I could get my son to play like that."

"Well, thanks again. We were really good. How old is your son?"

"I'm Shaq's daddy."

Beating No. 2 LSU earned us a trip to New York City to face No. 1 University of Nevada-Las Vegas. I went to Tavern on the Green for a press conference and they introduced me as Ron Williams. I stood up and said, "Folks, that doesn't bother me, because we are going to play our butts off and by the end of this tournament, you're going to know my first name."

UNLV had stars like Larry Johnson and Stacey Augmon and Greg Anthony and Anderson Hunt, all of whom would go on to play in the NBA. But I thought we could neutralize their pressure defense with backdoor cuts. We played almost a Princeton-style offense and they never figured us out. At one point in the second half we were up by 20 points and we ended up winning by 15. Their coach, Jerry Tarkanian, said afterward that he'd never had one of his teams handled like that.

L-R: Malik Sealy, Terry Brown, Lou Carnesecca

In the next game we played St. John's in the tournament final and nobody on our team could guard their start player, "Boo" Harvey. I remembered Coach (Dean) Smith once telling me

about New York Knicks coach Red Holzman's theory that sometimes creating an obvious mismatch disrupts the flow of the other team. St. John's had another good player named Malik Sealy, and so there was a timeout and I said, "Terry Brown, you guard Malik." Terry was a shooter who couldn't guard his lunch.

Terry looked at me and he said, "Malik?"

"Yeah, you guard Malik."

Sure enough, St. John's came down the court and Malik started yelling at everybody that he had a mismatch and he was posting Terry Brown up, and their coach, Louie Carnesecca, started screaming to throw the ball in to Malik. Malik got the ball and shot a turnaround jump shot over Terry and missed. We got the rebound and came down and scored. On their next possession, Malik was posting Terry up again, and they threw it in there and some way, somehow, Terry got around him and deflected the ball, and we stole it and ran down and scored again. They came down a third time, and again they were trying to set up Malik in the post. They threw it in to him, and he turned around and dribbled it off Terry's foot, and we picked it up and raced down and scored again. Louie called a timeout, and they stopped posting up Malik, but by that time, Boo Harvey was either out of sync or mad and he missed his next two or three shots, and we won the game.

We went from unranked to No. 4 in the country. We won our first 19 games and wound up spending 14 weeks that season ranked at No. 1 or No. 2.

The Jayhawks finished 30-5, losing to UCLA in the second round of the NCAA Tournament.

|

Bluegrass Madness

Blue Yonder, Lonnie Wheeler (1998)

In the dim morning light of April 2, 1996, less than seven hours after the University of

Kentucky had defeated Syracuse for its sixth collegiate basketball championship, a man on his way to work in Franklin County, Kentucky, noticed a peculiar smattering of blue in the roadside cemetery that he passed every day. Slowing his car and pulling closer to get a better look, he made out the letters "UK" on balloons that bobbed above three graves. Someone had tied them there in the night. ... The cemetery tableau was a dew-softened poster for those to whom Kentucky basketball has been handed down like a watch or a recipe or a certain way of stacking wood. For many of them, growing up in Kentucky involved two choices: watch the game or go outside and play. Such is the essential nature of Bluegrass basketball that it's often referred to as a religion, which speaks well for Kentucky's pastors. Blessed, indeed, is the church that is attended by as many Kentuckians as one of the coach's radio shows. The fact is that basketball simply means more in Kentucky than it does anywhere else; that it has more to do with how the state thinks of itself. While other places take the game seriously, Kentucky takes it personally. To an almost frightening extent, basketball is the thing Kentucky chooses for its identity. The distilleries and the horse farms and the coal mines tell the tales of their own sub-states, but basketball is the collected works, the treasury within which the far-flung Kentucky profiles are collated and bound. Basketball is what the commonwealth shares. There are times - say, from mid-November to early April - when one could make the forgivable mistake of thinking that basketball is what the commonwealth is. Suffice to say, Kentucky is a place that grows and smokes tobacco, makes and drinks bourbon, raises and races horses, mines and breathes coal, and sleeps and eats its favorite sport. In Kentucky, they even have a name for the basketball offseason. They call it the Kentucky Derby. It lasts a little longer if the track is sloppy.    L-R: Kyle Macy, Tony Delk, Cawood Ledford As for the trappings of obsession, Kentucky, of course, has notorious quantities of the basic stuff - weddings planned around the Cats' schedule, lifelong fans buried with pompons and autographed basketballs, blue and white caskets, inheritance battles over the season tickets, divorces complicated by two seats in the lower level, home libraries of game tapes, the Rick Pitino signature washer and dryer set ... Such is the renown of the Kentucky basketball fan, though, that those those things have practically become cliches. Everybody has a "Kentucky room" at home. Everybody has a son named Kyle. More revealing are the subtle daily manifestations of basketball's reach. There was the 1997 afternoon, for instance, when two women of the garden-club variety were browsing at the fashionable Joseph-Beth bookstore in Lexington and the one in the furry hat spotted a new book by the legendary Kentucky announcer, Cawood Ledford. "Oh there's Cawood's book," she said. Calling attention to the picture of a former player (Deron Feldhaus) in the cover collage, she asked her companion, "Now, who is that?" Standing nearby, I glanced at the picture and, noting the subject's dark hair and solid build, foolishly suggested that it might be Richie Farmer. "Oh," the lady replied, obviously knowing better but politely indulging my ignorance, "was that before Richie had his mustache?" I learned then and there never to presume to know more about Kentucky basketball than a Kentuckian, no matter what kind of hat she is wearing. There was also the occasion in 1996, when an unfortunate Harlan County teenager swerved to avoid hitting a dog and encountered a utility pole instead, knocking out power for the towns of Loyall and Baxer. The cool-headed investigating officer, aware, naturally, that the UK game was about to come on television, withheld the youngster's name for fear of what some of the less accommodating citizens might do to him. In Kentucky, the idea is to not let life interfere with basketball. |