Dippy's Youth - 1

Wilt: Larger Than Life, Robert Cherry (2004)

Born in 1936, Wilt Chamberlain grew up in West Philadelphia.

Born in 1936, Wilt Chamberlain grew up in West Philadelphia.

Surprisingly, the young Wilt disliked basketball, believing it was a game for sissies. What he loved to do was run. "I'd play kids' games with my brothers and sisters, games like hide-and-go-seek. Most of them were older than me, so I had to learn to run fast or I'd have never won a game."

Wilt attended George Brooks Elementary School, six blocks from his home, and there, as a member of the track team, he had his first contact with organized sports. ...

As a fourth-grader, Wilt was selected to anchor the school's 300-yard shuttle relay team in the renowned Penn Relays, the track competition held annually at Franklin Field on the University of Pennsylvania's campus. He also ran in a track event held in Convention Hall in Philadelphia where, many years later as a professional basketball player, he and Bill Russell would hold their titanic battles. But at this point in the story, he was a skinny fourth-grader running the final 75-yard lap, leading his team to victory. "The applause made me tingle all over," he remembered, vowing then and there to become a track star.

He undoubtedly would have, but for the changes to his body. By age 10 he was already 6' tall. By junior high school he couldn't keep track of his height, so quickly was he growing. "One summer I went down to Virginia for a vacation with some relatives, and when I came back home my sister Barbara met me at the door and said, 'Who are you? I don't know you.' She was probably kidding," concluded Wilt, "but I did look different. I had grown four inches."

Once asked by a high school teammate how he managed to have such a strong upper body while having such skinny legs, Wilt replied, "I used to go down and pick cotton at my uncle's place."

Wilt attended George Brooks Elementary School, six blocks from his home, and there, as a member of the track team, he had his first contact with organized sports. ...

As a fourth-grader, Wilt was selected to anchor the school's 300-yard shuttle relay team in the renowned Penn Relays, the track competition held annually at Franklin Field on the University of Pennsylvania's campus. He also ran in a track event held in Convention Hall in Philadelphia where, many years later as a professional basketball player, he and Bill Russell would hold their titanic battles. But at this point in the story, he was a skinny fourth-grader running the final 75-yard lap, leading his team to victory. "The applause made me tingle all over," he remembered, vowing then and there to become a track star.

He undoubtedly would have, but for the changes to his body. By age 10 he was already 6' tall. By junior high school he couldn't keep track of his height, so quickly was he growing. "One summer I went down to Virginia for a vacation with some relatives, and when I came back home my sister Barbara met me at the door and said, 'Who are you? I don't know you.' She was probably kidding," concluded Wilt, "but I did look different. I had grown four inches."

Once asked by a high school teammate how he managed to have such a strong upper body while having such skinny legs, Wilt replied, "I used to go down and pick cotton at my uncle's place."

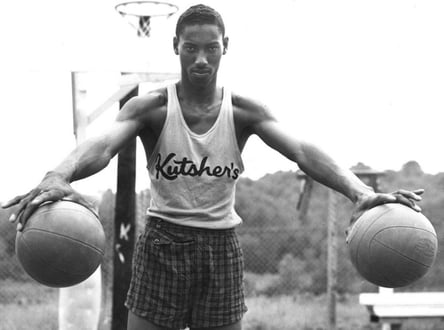

Young Wilt Chamberlain

It was during such summers in Virginia that mosquitoes mercilessly attacked him, leaving festering sores that permanently scarred his then-spindly legs. Self-conscious about the scars and his rail-thin legs, and wishing to protect himself from blows to his tender shins, Wilt wore knee pads over his shins and high socks when he realized that his size made him a natural for basketball. To keep the socks up, Wilt, who claimed he couldn't afford tape, used rubber bands. And to make sure he always had a ready supply, he slipped a wad of rubber bands around his wrist during a game. He wore rubber bands on his wrist off the court, as well, until he was about 45 years old - and they became his trademark. In a 1986 interview with Sports Illustrated, Frank Deford asked Wilt, "Where are the rubber bands?" Wilt's reply: "I kept wearing them because it reminded me of who I was, where I came from. Then suddenly, almost two years ago, I felt that I just didn't need that reminder anymore. ..." Another Wilt trademark was the headband, which he popularized as one of the first players to wear one when he played for the Los Angeles Lakers in the latter part of his career.

Wilt was particularly friendly with four neighborhood boys, all of whom attended elementary, junior high, and senior high school with him. Their bond was a love of basketball, and they spent much of their childhood at the nearby Haddington Recreation Center, where they learned to play the sport - indoors in winter, outdoors in summer. All five of these childhood friends ... eventually played on the same high school team. And of these close childhood friends, all but one were starters on their championship high school team. ...

"Some of his childhood friends and I always talk about how mature my brother was for his age," (Wilt's sister) Barbara recalled. "Maybe it was because he played on so many teams [with older players] once he decided, at age 13, on basketball. He played for the YMCA, ... the Police Athletic League [PAL], at the Haddington Recreation Center, and for the Vine Memorial and Mt. Carmel Baptist Churches." ...

In 1953 he led his YMCA team to the national title at High Point NC. ...

Wilt's siblings, childhood Philadelphia friends, and Overbrook High School classmates called him by the nicknames he preferred: "Dippy," "Dip," or "Dipper." ... Wilt explained in newspaper interviews the origin of his nickname:

In Wilt's time, the mid-fifties, Overbrook's student population was 60 to 70 percent white, 30 to 40 percent black. Almost all of the white students were lower-, middle-, or upper-middle-class Jews ...; the blacks were lower- to lower-middle-class from the formerly Jewish but, by mid-fifties, almost entirely black sections of West Philadelphia. The school had a proud academic and athletic tradition, with little, if any, racial tensions. ...

George Willner, an Overbrook graduate ..., recalled an incident in 1954 when Wilt came to the William B. Mann schoolyard in Wynnefield, which was Willmer's elementary school:

Wilt was particularly friendly with four neighborhood boys, all of whom attended elementary, junior high, and senior high school with him. Their bond was a love of basketball, and they spent much of their childhood at the nearby Haddington Recreation Center, where they learned to play the sport - indoors in winter, outdoors in summer. All five of these childhood friends ... eventually played on the same high school team. And of these close childhood friends, all but one were starters on their championship high school team. ...

"Some of his childhood friends and I always talk about how mature my brother was for his age," (Wilt's sister) Barbara recalled. "Maybe it was because he played on so many teams [with older players] once he decided, at age 13, on basketball. He played for the YMCA, ... the Police Athletic League [PAL], at the Haddington Recreation Center, and for the Vine Memorial and Mt. Carmel Baptist Churches." ...

In 1953 he led his YMCA team to the national title at High Point NC. ...

Wilt's siblings, childhood Philadelphia friends, and Overbrook High School classmates called him by the nicknames he preferred: "Dippy," "Dip," or "Dipper." ... Wilt explained in newspaper interviews the origin of his nickname:

When I was about 10, I was kind of big for my age, and I was always bumping my head in doorways and places where the ceilings were low. I was playing in an empty house one day with some boyfriends, and I ran smack into a low-hanging pipe and gave myself a beautiful black eye. My pals got a good laugh and told me next time I ought to dip under when I came to something like that. They started calling me "the Dipper" after that, and it became "Dipper" and then just "Dip" or "Dippy."

In the fifties one could field a top professional basketball team comprised only of players who had attended Philadelphia high schools, which is what Eddie Gottlieb, owner of the Philadelphia Warriors, did in the 1959-60 season. That squad featured Tom Gola, Ernie Beck, Paul Arizin, Guy Rodgers, and Wilt Chamberlain, all graduate of Philadelphia high schools (and all, save Wilt, graduates of Philadelphia colleges). ...In Wilt's time, the mid-fifties, Overbrook's student population was 60 to 70 percent white, 30 to 40 percent black. Almost all of the white students were lower-, middle-, or upper-middle-class Jews ...; the blacks were lower- to lower-middle-class from the formerly Jewish but, by mid-fifties, almost entirely black sections of West Philadelphia. The school had a proud academic and athletic tradition, with little, if any, racial tensions. ...

George Willner, an Overbrook graduate ..., recalled an incident in 1954 when Wilt came to the William B. Mann schoolyard in Wynnefield, which was Willmer's elementary school:

I'm 5'6" now, but at that time I was even shorter; and Wilt was 6'11". And it was me and Wilt against five other guys. He said to me, "Don't worry about it. Nobody's gonna score on us." And nobody did.

Larry Einhorn was nine or ten when, on another occasion, Wilt came to the Mann schoolyard:

In walked Wilt and Allan Weinberg, who played on the varsity with Wilt. What Wilt did, I'll never forget: to show his athletic prowess, he took a football and lifted his right leg and threw the football under his leg the length of the schoolyard.

In his later years, Wilt wore an Overbrook letter jacket for interviews, for appearances on television sports show, and to basketball games. ... On more than one occasion, Wilt said that his years at Overbrook were the happiest of his life. Dippy's Youth - 2

Wilt: Larger Than Life, Robert Cherry (2004)Read Dippy's Youth - 1.

Jack Ryan, sportswriter for the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, gave Wilt Chamberlain the nickname "Wilt the Stilt" when Dippy was a 6'11", 200lb sophomore at Overbrook High. Wilt hated the name until the day he died. "It makes me think of ... some freak in a sideshow," he said. He asked friends not to call him that. But headline writers loved it: "The Stilt Gets 44 as Overbrook Wins."

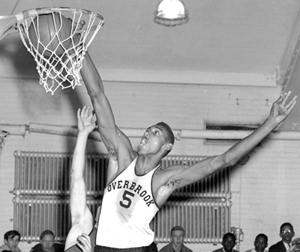

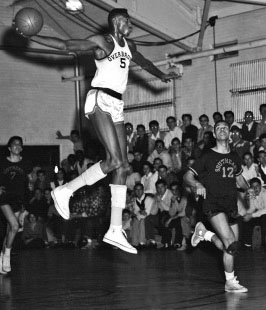

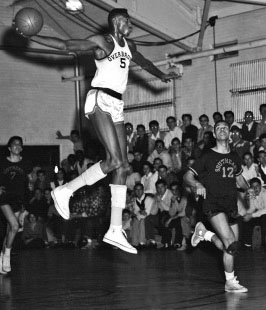

Overbrook won the Public League championship in Wilt's first season - his sophomore year. He tallied 34 points in the championship game against Northeast High School, whose star player was G Guy Rodgers, who would earn All-American honors at Temple University and play with Wilt on the Philadelphia Warriors as part of an NBA career that earned Guy a place in the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Overbrook then faced West Philadelphia Catholic, the defending city champion. Bob Devine, a member of the team who would play at Notre Dame, remembered how his team prepared to face Wilt.

In the spring, Wilt turned to his first love - track. He won the Public League high-jump championship as a sophomore. His high school coach said that Wilt's stride could have made him one of the best runners ever. If the money that is now available to world-class track stars had been available then and if professional athletes were allowed to compete in the Olympics, Wilt would have entered in the decathlon.

His junior year, Chamberlain scored a high school record 71 points in a game against Roxborough. Overbrook easily won the Public League title again with Wilt scoring 40 points in the final game against Northeast. Then he tallied 32 as the Panthers took the city title, defeating South Catholic 74-50 to complete a 19-0 season.

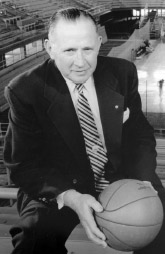

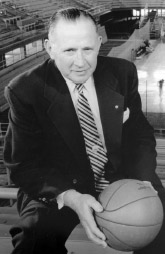

L-R: Chamberlain; B. H. Born; Red Auerbach

It was common in those days for summer resorts in the Catskill Mountains to hire college basketball players as bellhops, in part to play on the resorts' basketball league. Eddie Gottlieb, owner of the Philadelphia Warriors and one of the founders of the NBA, dreamed of Wilt playing for his club. He helped Wilt secure a summer job at Kutsher's Resort the summer between his junior and senior years of high school. The world's tallest bellhop made $13 a week plus tips. More importantly, he played for the resort basketball team. The coach was a young man whose parents, frequent guests at the hotel, asked the Kutshers to hire in 1950. His name was Arnold "Red" Auerbach, who became the coach of the Boston Celtics later that year.

That summer, 6'9" B. H. Born, who had just finished his career at Kansas, played against Wilt in the resort league. Born recalled: "Red Auerbach told Chamberlain that I was an All-American, the NCAA MVP, and I'd probably eat him up, so he was to just do the best he could against me. Until after the game, I couldn't understand why Wilt was so mad and trying so hard. Red had sicced him on me." Wilt, a high school junior, outscored Born, the college All-American, 25-10. "He just chewed me up," said Born. "I decided that if there were high school kids in that part of the country that good, I wasn't going to make it in the pros for very long." So Born eschewed the NBA and played industrial league basketball with the Caterpillar Tractor Company. Auerbach tried to convince Wilt to attend college in New England so that the Celtics, under the NBA's territorial draft rules, could draft him.

With the money he earned at Kutsher's, Wilt bought a 1947 Oldsmobile for $700. Buying cars and maintaining them would be a lifelong hobby for him.

By his senior year, Chamberlain was the most famous high school athlete in the country with articles about him in national magazines like Life and Sport. He was now an even 7' tall.

Overbrook lost only once his senior year, a controversial one-point defeat in a season-opening holiday tournament to Farrell High of Western PA. The officiating was so bad that the Farrell fans apologized to Wilt and his coach and teammates after the game.

Wilt broke his own scoring record in January with 74 points against poor Roxborough. The new mark lasted only a month until "Stodie" Watts scored 78 in a suburban Philadelphia league game. No problem. Wilt scored 90 the next week.

The Panthers easily won the Public League championship for the third straight year, beating West Philadelphia 78-60 in a game held at the Palestra on the University of Pennsylvania campus. In the city finals, Overbrook walloped West Catholic 83-42.

Wilt's high school athletic career wasn't over. After skipping track as a junior, he returned his senior year to win the Public League high-jump championship again, jumping 6'1". He also won the shot put title with a throw of 46'10 1/2."

All talk turned to where Wilt would attend college or if he would skip college and go directly to the NBA. To be continued ...

Overbrook won the Public League championship in Wilt's first season - his sophomore year. He tallied 34 points in the championship game against Northeast High School, whose star player was G Guy Rodgers, who would earn All-American honors at Temple University and play with Wilt on the Philadelphia Warriors as part of an NBA career that earned Guy a place in the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Overbrook then faced West Philadelphia Catholic, the defending city champion. Bob Devine, a member of the team who would play at Notre Dame, remembered how his team prepared to face Wilt.

We put a junior varsity player on a table in front of the basket. When we would shoot, he would knock down all the shots. And ... Brother Anthony ... ran around with a window pole. Every time we'd shoot, he would knock down the ball. We had to shoot higher so Wilt could not block our shots. We Just practiced all week long doing that.

The Catholic champs put four men on Chamberlain, two in front and two behind him. The fifth player ran the floor. Wilt scored 29 of Overbrook's 42 points, but his teammates played poorly. Also, Billy Lindsay of West Philadelphia Catholic had the game of his life, hitting 12 of 13 from the field and eight from the foul line for 32 points to lead West Catholic to the city championship, 54-42.

In the spring, Wilt turned to his first love - track. He won the Public League high-jump championship as a sophomore. His high school coach said that Wilt's stride could have made him one of the best runners ever. If the money that is now available to world-class track stars had been available then and if professional athletes were allowed to compete in the Olympics, Wilt would have entered in the decathlon.

His junior year, Chamberlain scored a high school record 71 points in a game against Roxborough. Overbrook easily won the Public League title again with Wilt scoring 40 points in the final game against Northeast. Then he tallied 32 as the Panthers took the city title, defeating South Catholic 74-50 to complete a 19-0 season.

L-R: Chamberlain; B. H. Born; Red Auerbach

That summer, 6'9" B. H. Born, who had just finished his career at Kansas, played against Wilt in the resort league. Born recalled: "Red Auerbach told Chamberlain that I was an All-American, the NCAA MVP, and I'd probably eat him up, so he was to just do the best he could against me. Until after the game, I couldn't understand why Wilt was so mad and trying so hard. Red had sicced him on me." Wilt, a high school junior, outscored Born, the college All-American, 25-10. "He just chewed me up," said Born. "I decided that if there were high school kids in that part of the country that good, I wasn't going to make it in the pros for very long." So Born eschewed the NBA and played industrial league basketball with the Caterpillar Tractor Company. Auerbach tried to convince Wilt to attend college in New England so that the Celtics, under the NBA's territorial draft rules, could draft him.

With the money he earned at Kutsher's, Wilt bought a 1947 Oldsmobile for $700. Buying cars and maintaining them would be a lifelong hobby for him.

By his senior year, Chamberlain was the most famous high school athlete in the country with articles about him in national magazines like Life and Sport. He was now an even 7' tall.

Overbrook lost only once his senior year, a controversial one-point defeat in a season-opening holiday tournament to Farrell High of Western PA. The officiating was so bad that the Farrell fans apologized to Wilt and his coach and teammates after the game.

Wilt broke his own scoring record in January with 74 points against poor Roxborough. The new mark lasted only a month until "Stodie" Watts scored 78 in a suburban Philadelphia league game. No problem. Wilt scored 90 the next week.

The Panthers easily won the Public League championship for the third straight year, beating West Philadelphia 78-60 in a game held at the Palestra on the University of Pennsylvania campus. In the city finals, Overbrook walloped West Catholic 83-42.

Wilt's high school athletic career wasn't over. After skipping track as a junior, he returned his senior year to win the Public League high-jump championship again, jumping 6'1". He also won the shot put title with a throw of 46'10 1/2."

All talk turned to where Wilt would attend college or if he would skip college and go directly to the NBA. To be continued ...

Dippy's Youth - 3

Wilt: Larger Than Life, Robert Cherry (2004)

In the early years, the National Basketball Association had both a regular and a territorial draft, the latter of which allowed a team to draft a college player from its geographical area in exchange for a first-round draft pick. The thinking among the NBA owners was that local college stars would attract fans and alumni to the professional game - and the struggling league needed all the fan support it could muster. The draft radius extended 50 miles from the city in which the professional team was located.

With Wilt Chamberlain due to graduate from high school, Eddie Gottlieb lobbied to change the territorial draft to include high school players. Ned Irish, the equally strong-willed owner of the New York Knickerbockers, was against such a modification, but Gottlieb prevailed and the league owners voted seven to one for the new rule in April 1955. Soon thereafter, Gottlieb became the first person to invoke the territorial draft to secure the right to a high school athlete, picking Wilt four years in advance of the 1959 draft. Luckily for Gottlieb - though some would say luck had nothing to do with it - Wilt did not attend a college in a city located within 50 miles of an NBA team, for in that case Gottlieb's Warriors would have lost the rights to Wilt in the 1959 draft. ...

No athlete before, and not many since, has been pursued by as many colleges as was Wilt. In this, as in so many areas, he was the "first." "He got 120 offers," recalled Cecil Mosenson (Wilt's high school coach). "UCLA told him they'd make him a movie star. Other colleges told him they'd send him to dental or medical school. An alumnus from the University of Pennsylvania came over in a big limousine and said, 'Wilt, why don't we take a ride to New York tomorrow and take a look at what Harry Winston, the big jeweler, has." Coach Mosenson was even offered a coaching position - if he could deliver Wilt.

Where will Wilt go? The sporting public - and more than a few college coaches and boosters - wondered in the winter and spring of 1955. How big a story was it? After Wilt selected a college, Life, then the most popular magazine in the country, featured a five-page story on the effort to recruit and land him.

L-R: Wilt Chamberlain in Life magazine, Eddie Gottlieb, Phog Allen

Wilt wanted to

attend college outside Philadelphia, great as the Philly tradition in college basketball was - and is. "He didn't want another big city," recalled George L. Brown, a friend and adviser. Southern schools did not want blacks at that time, so that eliminated the great basketball power Kentucky. When people thought of college basketball in 1955, no one thought of the far West or Pacific Northwest. ...

Wilt wasn't interested in New England and passed on New York because he didn't want to be that close to Philadelphia. So that left the Midwest, whose colleges produced some of the country's finest basketball and where Wilt visited the numerous universities, including Kansas.

Don Pierce, then sports information director at Kansas University, saw a photo of Wilt in 1952 and has been credited with bringing Wilt to the attention of the school's basketball coach, the legendary Forrest "Phog" Allen, whose voice supposedly sounded like a fog horn, thus the memorable nickname. And surely B. H. Born, the Kansas All-American almost run off the court by Wilt in the summer of 1954 in the Catskills, had told Phog about the young Philly phenom.

But it wasn't until the winter of 1955 that Allen began to recruit Wilt and actually saw him play. Allen flew to Philadelphia in January 1955 and attended the Overbrook-Germantown game. That evening Wilt received a local award as "the outstanding scholastic athlete in Philadelphia." Coach Cecil Mosenson recaptured the event: "Phog Allen came to the Clivenden Award Banquet and introduced himself to me. Then he sat down with Wilt's mother and he schmoozed her. And she loved him."

When Mosenson and Mrs. Chamberlain talk to Stilt about attending Kansas, Wilt was not enthused, but because the school sent plane tickets, Wilt and Mosenson took a trip to Lawrence, Kansas, a lovely university town located 40 miles from Kansas City. Mosenson recalled that "before taking off, it was snowing, and they had to deice the plane. When we arrived in Lawrence at about 3:00 in the morning, there must have been 50 people waiting for us."

Phog Allen assembled a lineup of distinguished Kansas citizens, black and white, to win Wilt's heart for the university. ...

"It was common knowledge that Eddie Gottlieb also encouraged Wilt to go to college in Kansas in order to keep him away from an NBA city," alleged the late Alex Hannum, who had been an NBA coach. Even if true, there were other Midwestern schools that would have enabled Gottlieb to select Wilt under the territorial draft because there was not a professional basketball team within 50 miles of them.

What Kansas most had in its favor was Phog Allen, one of college basketball's greatest coaches. Allen won or shared 24 conference championships in his 39 years at Kansas ... and had helped to coach the United States Olympic team to a gold medal in 1952. ...

There was one more element in Wilt's decision, although it was not likely the deciding factor: "There were incentives," Wilt's high school coach, Cecil Mosensen, recalled. ... And unless you believe in the tooth fairy, one has to assume that many other schools pursuing Wilt also offered "incentives," by which coach Mosenson means money. Wilt told reporters for several New York newspapers in 1985 that he received approximately $4,000 from "two or three godfathers" when he played at Kansas. This was in addition to the standard college scholarship of the time, which in 1955 included free room and board, tuition and books, plus $135 a year for selling football programs and helping with other athletic jobs, which was worth about $1,100 per year in 2002 dollars.

Told that Wilt Chamberlain had selected Kansas from the hundred-plus schools that had pursued him, Phog Allen is reported to have said, "I hope he comes out for basketball."

With Wilt Chamberlain due to graduate from high school, Eddie Gottlieb lobbied to change the territorial draft to include high school players. Ned Irish, the equally strong-willed owner of the New York Knickerbockers, was against such a modification, but Gottlieb prevailed and the league owners voted seven to one for the new rule in April 1955. Soon thereafter, Gottlieb became the first person to invoke the territorial draft to secure the right to a high school athlete, picking Wilt four years in advance of the 1959 draft. Luckily for Gottlieb - though some would say luck had nothing to do with it - Wilt did not attend a college in a city located within 50 miles of an NBA team, for in that case Gottlieb's Warriors would have lost the rights to Wilt in the 1959 draft. ...

No athlete before, and not many since, has been pursued by as many colleges as was Wilt. In this, as in so many areas, he was the "first." "He got 120 offers," recalled Cecil Mosenson (Wilt's high school coach). "UCLA told him they'd make him a movie star. Other colleges told him they'd send him to dental or medical school. An alumnus from the University of Pennsylvania came over in a big limousine and said, 'Wilt, why don't we take a ride to New York tomorrow and take a look at what Harry Winston, the big jeweler, has." Coach Mosenson was even offered a coaching position - if he could deliver Wilt.

Where will Wilt go? The sporting public - and more than a few college coaches and boosters - wondered in the winter and spring of 1955. How big a story was it? After Wilt selected a college, Life, then the most popular magazine in the country, featured a five-page story on the effort to recruit and land him.

L-R: Wilt Chamberlain in Life magazine, Eddie Gottlieb, Phog Allen

Wilt wasn't interested in New England and passed on New York because he didn't want to be that close to Philadelphia. So that left the Midwest, whose colleges produced some of the country's finest basketball and where Wilt visited the numerous universities, including Kansas.

Don Pierce, then sports information director at Kansas University, saw a photo of Wilt in 1952 and has been credited with bringing Wilt to the attention of the school's basketball coach, the legendary Forrest "Phog" Allen, whose voice supposedly sounded like a fog horn, thus the memorable nickname. And surely B. H. Born, the Kansas All-American almost run off the court by Wilt in the summer of 1954 in the Catskills, had told Phog about the young Philly phenom.

But it wasn't until the winter of 1955 that Allen began to recruit Wilt and actually saw him play. Allen flew to Philadelphia in January 1955 and attended the Overbrook-Germantown game. That evening Wilt received a local award as "the outstanding scholastic athlete in Philadelphia." Coach Cecil Mosenson recaptured the event: "Phog Allen came to the Clivenden Award Banquet and introduced himself to me. Then he sat down with Wilt's mother and he schmoozed her. And she loved him."

When Mosenson and Mrs. Chamberlain talk to Stilt about attending Kansas, Wilt was not enthused, but because the school sent plane tickets, Wilt and Mosenson took a trip to Lawrence, Kansas, a lovely university town located 40 miles from Kansas City. Mosenson recalled that "before taking off, it was snowing, and they had to deice the plane. When we arrived in Lawrence at about 3:00 in the morning, there must have been 50 people waiting for us."

Phog Allen assembled a lineup of distinguished Kansas citizens, black and white, to win Wilt's heart for the university. ...

"It was common knowledge that Eddie Gottlieb also encouraged Wilt to go to college in Kansas in order to keep him away from an NBA city," alleged the late Alex Hannum, who had been an NBA coach. Even if true, there were other Midwestern schools that would have enabled Gottlieb to select Wilt under the territorial draft because there was not a professional basketball team within 50 miles of them.

What Kansas most had in its favor was Phog Allen, one of college basketball's greatest coaches. Allen won or shared 24 conference championships in his 39 years at Kansas ... and had helped to coach the United States Olympic team to a gold medal in 1952. ...

There was one more element in Wilt's decision, although it was not likely the deciding factor: "There were incentives," Wilt's high school coach, Cecil Mosensen, recalled. ... And unless you believe in the tooth fairy, one has to assume that many other schools pursuing Wilt also offered "incentives," by which coach Mosenson means money. Wilt told reporters for several New York newspapers in 1985 that he received approximately $4,000 from "two or three godfathers" when he played at Kansas. This was in addition to the standard college scholarship of the time, which in 1955 included free room and board, tuition and books, plus $135 a year for selling football programs and helping with other athletic jobs, which was worth about $1,100 per year in 2002 dollars.

Told that Wilt Chamberlain had selected Kansas from the hundred-plus schools that had pursued him, Phog Allen is reported to have said, "I hope he comes out for basketball."

Survive and Advance - 1

Valvano: They Gave Me a Lifetime Contract, and Then They Declared Me Dead,

Jim Valvano and Curry Kirkpatrick (1991)

Jim Valvano and Curry Kirkpatrick (1991)

Jim Valvano entered his third season as head coach at North Carolina State.

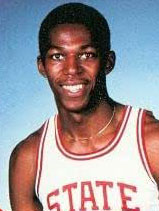

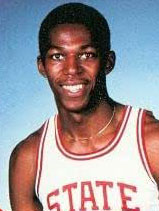

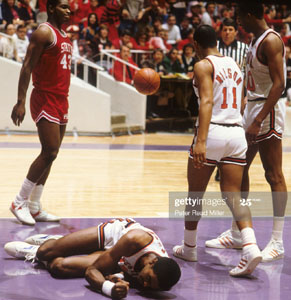

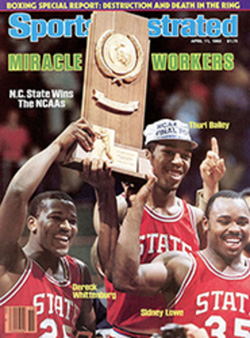

The reason I was so confident going into the season of 1982-83 had nothing to do with how good I thought our team might be on the court, but it had everything to do with what had happened off it. I loved our personnel: I figured Sidney Lowe and Dereck Whittenburg would be one of the best guard combinations in the country. We also had a little mad bomber in Terry Gannon and a very talented freshman scorer in Ernie Myers. That backcourt would be simply terrific. Up front, Thurl Bailey was just coming into his own as a senior; he was a late developer who would go on to have an illustrious career at Utah in the NBA. This was our nucleus of veterans. But we also had two younger players, "Co and Lo" (Cozell McQueen and Lorenzo Charles), something we really had been missing in the past two years: a center who could neutralize the middle and a crunching power forward to muscle the boards. ...

That previous spring, we (ACC coaches) voted to recommend to our athletic directors that the ACC institute the three-point shot and the 30-second clock. This came about after some long and, shall we say, vociferous infighting among those present. ...

I felt that the clock and the three-pointer would be good for game, but by the same token I had a team that was not suited for an up-tempo contest. In addition, we were one of the biggest culprits in stall ball. I had to do what was best for my ball club. I had a hard time explaining my contradictory thoughts on the subject. I did know this: If I went through another year of coaching like the last one, I would blow my brains out.

Ours had become a game of coaches, not players. We had taken a beautiful, action-packed thing and made it into a chess match. It took about as long as a game of chess, and about as many points were scored. It was ridiculous and horrible. The players all wanted to play, not hang back. The fans wanted it; everybody wanted it. ...

Twelve other conferences would legislate new rules over the summer; we were the catalyst for the whole country. And we wanted to make a bold statement - even though we'd have to adjust back to the old rules during the NCAA tournament, and we knew that might hurt our teams. We ended up with the shortest (shot) clock and the shortest (three-point) distance. The game in the ACC was the most fun in all of college. And a blast for North Carolina State.

The changes helped us win the national championship, to be precise.

I kept thinking about how the '82-'83 Wolfpack could combine the best of our first two years in Raleigh. My first season we ran well, but we didn't have a good halfcourt offense. The second year we played excellent defense ... But we didn't run at all. That's when I first put together my plan for two different styles of ball on the same team. With a three-guard lineup, we could press and run. I also had the personnel for a power lineup that could be deliberate and pound it inside. ...

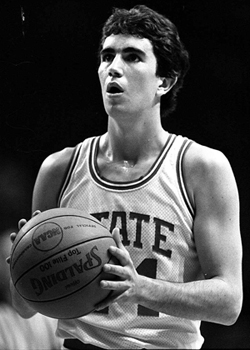

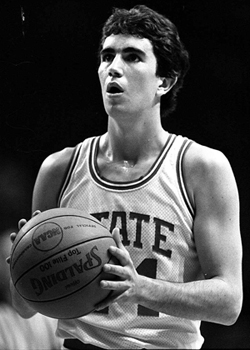

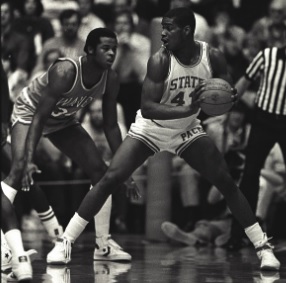

L-R: Jim Valvano, Sidney Lowe, Dereck Whittenburg, Thurl Bailey

The first big game for us was Michigan State at home. I knew the Spartans would spread the court and slow the tempo. Our new rules only applied to league games, unless the opponent agreed to them. Jud Heathcote, the Michigan State coach, didn't. So it was a game like the year before, and they had three future pros, Sam Vincent, Kevin Willis, and Scott Skiles, playing it.

It turned out to be a heck of a game with a great ending. We were ahead by two points with 17 seconds left, when Michigan State called time-out with the ball. Vincent had been killing us all night, so we decided to go with a 1-3 zone and a chaser. But who would chase Sam?

We had a guy named Harold Thompson who had earned his scholarship every year by winning a game for us defensively. He was the obvious choice, but Harold had only played a few seconds in the game. What happened if they shot early, missed, then fouled Harold? What if he missed and they got another chance? What if? What if? Our entire defense would be based on Harold's ability to stop Vincent. This was risky, which is what bench coaching is all about. If it works, you're smart. If it doesn't, you're a bum.

What happened? Harold stole the in-bounds pass, Thurl hit a couple of foul shots, we won 45-41 and I avoided being a bum for another day. ...

We played a series of games under both the new and the old rules: winning against Clemson 76-70 under the new, losing to Missouri under the old; and losing to Ralph Sampson and the Cavs 88-80 in a heartbreaking game in which Dereck Whittenburg broke his foot.

Starting with Georgia Tech in Raleigh (whom we blew away) and ending with Duke in Durham (whom we also blew away), there was a 14-game stretch which I have always referred to as our season-within-a-season. Obviously, we had to start all over. What style do we play? What kind of defense? What's the rotation on substitutions? We thought Whittenburg was gone for the season, when in actuality he did return after those 14 games. But it was a different team he returned to, a better team, a team that had found itself, a team that would go on to win the national championship. And that season-within-a-season was the foundation.

I still think it's the best coaching job our staff ever did. We started out 2-4, then won seven of our next eight games. Had it not been for a one-point loss to Notre Dame, we'd have nailed all eight. And the unsung hero was Ernie Myers.

Ernie started off by scoring 27 points against Georgia Tech. That was great. But the education of our new team started in a beating by North Carolina. Before the game, I showed Ernie the backdoor play Carolina likes to run. I told the staff he'd get beat the first time they tried it, and sure enough, Michael Jordan whipped by him right away. Ernie looked over at me on the bench and just shook his head.

That was all right. Even the 18-point licking was all right. What I couldn't stand was that for the first time, I felt the team didn't believe me. They didn't believe we could get the job done without Whitt. I ripped into them in the locker room. "If you guys don't believe, if any of you can't have the same dream I do, then get the hell out of here because I don't want you around. If it's three or five or whatever, we'll go on without you. We lost a player, but that's over with. I didn't promise it would be easy. It's a long, hard struggle. But we will get this thing done with or without you."

That previous spring, we (ACC coaches) voted to recommend to our athletic directors that the ACC institute the three-point shot and the 30-second clock. This came about after some long and, shall we say, vociferous infighting among those present. ...

I felt that the clock and the three-pointer would be good for game, but by the same token I had a team that was not suited for an up-tempo contest. In addition, we were one of the biggest culprits in stall ball. I had to do what was best for my ball club. I had a hard time explaining my contradictory thoughts on the subject. I did know this: If I went through another year of coaching like the last one, I would blow my brains out.

Ours had become a game of coaches, not players. We had taken a beautiful, action-packed thing and made it into a chess match. It took about as long as a game of chess, and about as many points were scored. It was ridiculous and horrible. The players all wanted to play, not hang back. The fans wanted it; everybody wanted it. ...

Twelve other conferences would legislate new rules over the summer; we were the catalyst for the whole country. And we wanted to make a bold statement - even though we'd have to adjust back to the old rules during the NCAA tournament, and we knew that might hurt our teams. We ended up with the shortest (shot) clock and the shortest (three-point) distance. The game in the ACC was the most fun in all of college. And a blast for North Carolina State.

The changes helped us win the national championship, to be precise.

I kept thinking about how the '82-'83 Wolfpack could combine the best of our first two years in Raleigh. My first season we ran well, but we didn't have a good halfcourt offense. The second year we played excellent defense ... But we didn't run at all. That's when I first put together my plan for two different styles of ball on the same team. With a three-guard lineup, we could press and run. I also had the personnel for a power lineup that could be deliberate and pound it inside. ...

L-R: Jim Valvano, Sidney Lowe, Dereck Whittenburg, Thurl Bailey

It turned out to be a heck of a game with a great ending. We were ahead by two points with 17 seconds left, when Michigan State called time-out with the ball. Vincent had been killing us all night, so we decided to go with a 1-3 zone and a chaser. But who would chase Sam?

We had a guy named Harold Thompson who had earned his scholarship every year by winning a game for us defensively. He was the obvious choice, but Harold had only played a few seconds in the game. What happened if they shot early, missed, then fouled Harold? What if he missed and they got another chance? What if? What if? Our entire defense would be based on Harold's ability to stop Vincent. This was risky, which is what bench coaching is all about. If it works, you're smart. If it doesn't, you're a bum.

What happened? Harold stole the in-bounds pass, Thurl hit a couple of foul shots, we won 45-41 and I avoided being a bum for another day. ...

We played a series of games under both the new and the old rules: winning against Clemson 76-70 under the new, losing to Missouri under the old; and losing to Ralph Sampson and the Cavs 88-80 in a heartbreaking game in which Dereck Whittenburg broke his foot.

Starting with Georgia Tech in Raleigh (whom we blew away) and ending with Duke in Durham (whom we also blew away), there was a 14-game stretch which I have always referred to as our season-within-a-season. Obviously, we had to start all over. What style do we play? What kind of defense? What's the rotation on substitutions? We thought Whittenburg was gone for the season, when in actuality he did return after those 14 games. But it was a different team he returned to, a better team, a team that had found itself, a team that would go on to win the national championship. And that season-within-a-season was the foundation.

I still think it's the best coaching job our staff ever did. We started out 2-4, then won seven of our next eight games. Had it not been for a one-point loss to Notre Dame, we'd have nailed all eight. And the unsung hero was Ernie Myers.

Ernie started off by scoring 27 points against Georgia Tech. That was great. But the education of our new team started in a beating by North Carolina. Before the game, I showed Ernie the backdoor play Carolina likes to run. I told the staff he'd get beat the first time they tried it, and sure enough, Michael Jordan whipped by him right away. Ernie looked over at me on the bench and just shook his head.

That was all right. Even the 18-point licking was all right. What I couldn't stand was that for the first time, I felt the team didn't believe me. They didn't believe we could get the job done without Whitt. I ripped into them in the locker room. "If you guys don't believe, if any of you can't have the same dream I do, then get the hell out of here because I don't want you around. If it's three or five or whatever, we'll go on without you. We lost a player, but that's over with. I didn't promise it would be easy. It's a long, hard struggle. But we will get this thing done with or without you."

Survive and Advance - 2

Valvano: They Gave Me a Lifetime Contract, and Then They Declared Me Dead,

Jim Valvano and Curry Kirkpatrick (1991)

Jim Valvano and Curry Kirkpatrick (1991)

I was 8-6, my best player had a broken foot, and Carolina had beaten us seven times in a row, when I got a call from (Athletic Director) Willis Casey. Many thoughts went through my mind on the way to his office. I was pleasantly surprised when Willis informed me that, not only was he pleased with my performance, but he wanted to discuss a long-term contract. Dean Smith had recently signed a 10-year contract at Chapel Hill, and Willis felt that the basketball coach at State should have the same. Considering that Dean had won a national championship, an Olympic gold medal, and was one of the winningest coaches in the history of the game - my being 8-6, I thought it was a fair offer. I always felt that Willis' confidence in me was one of the things that enabled me to coach the team to a national championship. ...

Among other things, coaches are basically schizophrenic. We are pessimistic to the press and among fellow coaches, but to our teams, we are the eternal optimists. This was true for the Carolina game, as well. The closer we got to this one, I talked publicly about how great the Heels were and how many things could go wrong for us. It was all negative. In the locker room, however, I was extremely positive to the team, telling them how well they'd prepared and practiced. "We're ready, gentlemen," I said. "There is no way you can lose this one tonight." Then, after they'd left, I turned to my staff and said: "No shot. Geez, these poor kids could get absolutely killed."

However, this time we played a strong game from start to finish. Two technical fouls on Carolina in the first half may have been the key. (Terry) Gannon hit four free throws, and we led at the half, 37-36. We built the lead to seven points late in the game before our foul shooting went south. Then, we missed three straight one-and-ones and I started panicking on the bench. "Can't anyone make a damn free throw?" I screamed.

"I can," said a voice from down the bench. It was none other than Cozell McQueen, who was not famous for his pinpoint foul shooting. What the heck, I thought, nobody else could make them. Immediately, Carolina fouled McQueen and with 17 seconds left and N.C. State leading by 66-63, he calmly hit two big ones to clinch our victory over the Heels.

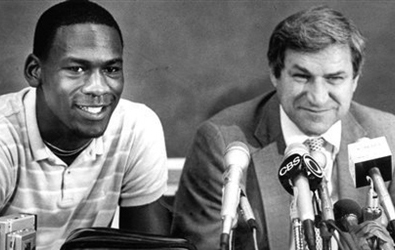

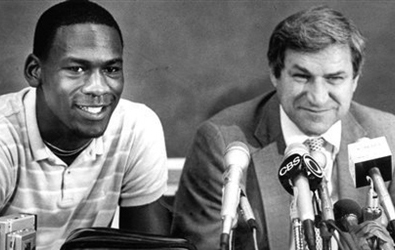

L-R: Terry Gannon, Cozell McQueen, Michael Jordan and Dean Smith

This was the game where Michael Jordan scored 17 points and Gannon scored 15. It was the game Lowe finished off by bounce-passing through his legs to Bailey for a game-ending dunk. It was the game after which the State kids cut the nets down. Late in the game, Dean came over to say he was happy for me, and I believe he was sincere. How could anybody not be happy for me? Dean had won only eight thousand games; gimme one or two somewhere.

It had been quite a while since State had beaten Carolina in football or basketball, and our fans celebrated in Reynolds for more than an hour. No one would leave. The rush of emotion made me so giddy - we had played with the clock, beaten a great team, gone up and down with them and actually won - that I felt we could beat anybody. At one time, amid all the celebration, Whittenburg himself was sitting up on the goal, dressed in street clothes. If that wasn't a true vision of the future, I don't know what was. One week and one day later Whitt was back in the N.C. State lineup. ...

Although Whitt rejoined the team, we now had to adjust to his presence, and in fact, we lost to Virginia and then to Maryland.

After the Maryland game, I was very disappointed. I thought our tenth loss had critically hurt our NCAA chances. Everybody was talking about us going NIT now. But then came Senior Day against Wake Forest, the final home game in Reynolds, and the team exploded for 130 points, the highest total of any team in the conference that season. ... Threes? Try 16 three-pointers for the Wolfpack. I think Mama Valvano could have hit a couple of threes that afternoon.

It was precisely the way we were playing nearly two months before, when Whittenburg broke his foot. The ironic thing was that I feared we still could get left out of the NCAA bids unless we won the ACC tournament. I felt that three bids were locks from the ACC - Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland - and the fourth would be between us and Wake Forest. And, to boot, our first-round game in the ACC's was against Wake, the team we had just destroyed by 41 points.

You think I'm crazy, right? Well, in Atlanta at the ACC's, Wake cut the deficit by a cool 40. That's right, we won by the skin of our wolf-teeth, 71-70, and only because Danny Young barely missed a shot from halfcourt at the gun. Looking back, the significant decision came with about 20 seconds left when Wake called time-out with the score tied at 70. Unlike what we later did all through the NCAA tournament, this time we elected not to foul. I didn't want them on the line. I just felt we could make a defensive play, so I told our guys to get in their faces, make them beat us. If we were going to lose, lose aggressively. Sure enough, Lowe made a steal, giving us the ball. After our own time-out, Charles was fouled and made the winning free throw.

Game number two ... was against North Carolina. ... The game was strange. We led by five late in the second half, but Carolina came back to tie. We had the last shot, but Lowe got stripped and Carolina got the final try instead, a 30-footer by Sam Perkins that just missed. I watched that baby from an angle and it looked in all the way. I think it took five minutes to get there. I know it took five minutes off my life. Actually, the ball did go in. Then it came out. In the overtime, the Heels mirrored that shot. They were in, then out. Carolina seemed to have the game locked up with a six-point lead and 2:13 left, but then we resorted to the strategy that we would use throughout our journey to the NCAA championship the next month. How can I put this in the simplest way? Okay; we fouled.

Sonofagun. Deano was way ahead of me here, too. My staff had always discussed a special strategy where if we had a lead late in the game and the other team was fouling us and we made our two free throws, why not foul them back? The best they can do is make their two, you get the ball and the situation is the same. Even if you miss yours, foul the other team's worst shooter. He may miss and you lose nothing. That's in lieu of letting the other team shoot the three and go ahead and maybe beat you. Well, that's exactly what Dean did in this game. Rather than permit us to foul, have the Heels shoot one-and-ones and then have us look for the three-point bombs, Dean fouled us back to put pressure on us. I recall shouting, "They're fouling us!" more than a few times. It was a gutsy strategy.

Luckily for us, though, we made our free throws and the Heels missed theirs. We cut the lead to four, Wittenburg swished a three-pointer and later drove the baseline for a score. Held in check through regulation, Dereck scored 11 points in the overtime and we won 91-84.

Now we were finally in the ACC finals, on the cusp on one of my fondest dreams, winning the ACC title. ...

Among other things, coaches are basically schizophrenic. We are pessimistic to the press and among fellow coaches, but to our teams, we are the eternal optimists. This was true for the Carolina game, as well. The closer we got to this one, I talked publicly about how great the Heels were and how many things could go wrong for us. It was all negative. In the locker room, however, I was extremely positive to the team, telling them how well they'd prepared and practiced. "We're ready, gentlemen," I said. "There is no way you can lose this one tonight." Then, after they'd left, I turned to my staff and said: "No shot. Geez, these poor kids could get absolutely killed."

However, this time we played a strong game from start to finish. Two technical fouls on Carolina in the first half may have been the key. (Terry) Gannon hit four free throws, and we led at the half, 37-36. We built the lead to seven points late in the game before our foul shooting went south. Then, we missed three straight one-and-ones and I started panicking on the bench. "Can't anyone make a damn free throw?" I screamed.

"I can," said a voice from down the bench. It was none other than Cozell McQueen, who was not famous for his pinpoint foul shooting. What the heck, I thought, nobody else could make them. Immediately, Carolina fouled McQueen and with 17 seconds left and N.C. State leading by 66-63, he calmly hit two big ones to clinch our victory over the Heels.

L-R: Terry Gannon, Cozell McQueen, Michael Jordan and Dean Smith

It had been quite a while since State had beaten Carolina in football or basketball, and our fans celebrated in Reynolds for more than an hour. No one would leave. The rush of emotion made me so giddy - we had played with the clock, beaten a great team, gone up and down with them and actually won - that I felt we could beat anybody. At one time, amid all the celebration, Whittenburg himself was sitting up on the goal, dressed in street clothes. If that wasn't a true vision of the future, I don't know what was. One week and one day later Whitt was back in the N.C. State lineup. ...

Although Whitt rejoined the team, we now had to adjust to his presence, and in fact, we lost to Virginia and then to Maryland.

After the Maryland game, I was very disappointed. I thought our tenth loss had critically hurt our NCAA chances. Everybody was talking about us going NIT now. But then came Senior Day against Wake Forest, the final home game in Reynolds, and the team exploded for 130 points, the highest total of any team in the conference that season. ... Threes? Try 16 three-pointers for the Wolfpack. I think Mama Valvano could have hit a couple of threes that afternoon.

It was precisely the way we were playing nearly two months before, when Whittenburg broke his foot. The ironic thing was that I feared we still could get left out of the NCAA bids unless we won the ACC tournament. I felt that three bids were locks from the ACC - Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland - and the fourth would be between us and Wake Forest. And, to boot, our first-round game in the ACC's was against Wake, the team we had just destroyed by 41 points.

You think I'm crazy, right? Well, in Atlanta at the ACC's, Wake cut the deficit by a cool 40. That's right, we won by the skin of our wolf-teeth, 71-70, and only because Danny Young barely missed a shot from halfcourt at the gun. Looking back, the significant decision came with about 20 seconds left when Wake called time-out with the score tied at 70. Unlike what we later did all through the NCAA tournament, this time we elected not to foul. I didn't want them on the line. I just felt we could make a defensive play, so I told our guys to get in their faces, make them beat us. If we were going to lose, lose aggressively. Sure enough, Lowe made a steal, giving us the ball. After our own time-out, Charles was fouled and made the winning free throw.

Game number two ... was against North Carolina. ... The game was strange. We led by five late in the second half, but Carolina came back to tie. We had the last shot, but Lowe got stripped and Carolina got the final try instead, a 30-footer by Sam Perkins that just missed. I watched that baby from an angle and it looked in all the way. I think it took five minutes to get there. I know it took five minutes off my life. Actually, the ball did go in. Then it came out. In the overtime, the Heels mirrored that shot. They were in, then out. Carolina seemed to have the game locked up with a six-point lead and 2:13 left, but then we resorted to the strategy that we would use throughout our journey to the NCAA championship the next month. How can I put this in the simplest way? Okay; we fouled.

Sonofagun. Deano was way ahead of me here, too. My staff had always discussed a special strategy where if we had a lead late in the game and the other team was fouling us and we made our two free throws, why not foul them back? The best they can do is make their two, you get the ball and the situation is the same. Even if you miss yours, foul the other team's worst shooter. He may miss and you lose nothing. That's in lieu of letting the other team shoot the three and go ahead and maybe beat you. Well, that's exactly what Dean did in this game. Rather than permit us to foul, have the Heels shoot one-and-ones and then have us look for the three-point bombs, Dean fouled us back to put pressure on us. I recall shouting, "They're fouling us!" more than a few times. It was a gutsy strategy.

Luckily for us, though, we made our free throws and the Heels missed theirs. We cut the lead to four, Wittenburg swished a three-pointer and later drove the baseline for a score. Held in check through regulation, Dereck scored 11 points in the overtime and we won 91-84.

Now we were finally in the ACC finals, on the cusp on one of my fondest dreams, winning the ACC title. ...

Continued below ...

Survive and Advance - 3

Valvano: They Gave Me a Lifetime Contract, and Then They Declared Me Dead,

Jim Valvano and Curry Kirkpatrick (1991)

Jim Valvano and Curry Kirkpatrick (1991)

Read Survive and Advance - 1 | Read Survive and Advance - 2

North Carolina State has reached the 1983 ACC Tournament final.

North Carolina State has reached the 1983 ACC Tournament final.

I still laugh when I read that because the ACC tournament no longer decides the only NCAA representatives, the intensity and desire to win it are diminished. What a crock! I'll tell you one thing: We were fairly fired up. We were about to play Virginia, the best college team over the past for years, with the nation's premier player in Ralph Sampson and with a winning streak of three YEARS against us. We were probably as emotional for that game as any in my entire tenure in Raleigh.

We came out smoking and led 12-1. Remember, we had been ahead of these guys by 16 points back in January, so we knew they could be had. As seemed to happen every game, though, we couldn't stand prosperity. Virginia came back and led 59-51 with about eleven minutes left in the game. ... But there was plenty of time left. Another terrific State comeback - we went ahead by nine points - only enabled us to withstand still another embarrassing drought fromt he foul line. We kept missing free throws, and the clock didn't seem to move.

Our lead was still three points when the littlest player in the game made the biggest play. As Sampson went up for a shot on the inside, Terry Gannon stripped him clean. Ralph had 24 points and 12 rebounds, but Thurl Bailey matched Sampson's points and Lorenzo Charles matched his rebounds for us. Nevertheless, if Sampson had scored there and maybe gotten fouled, the game might have been tied.

As it was, we kept our three-point lead until there was six seconds left, Virginia ball. We had decided to try to keep the ball from Othell Wilson. In fact, we were successful in doing this, and Doug Newburg, not nearly as quick as Wilson, was forced to dribble up the court and make the play. Our pressure was successful; Newburg finally passed off, but the shot came after the buzzer. We were the new ACC champions.

Of course, I cried. Standing there watching the joy on all our players' faces, I couldn't imagine feeling any better or more fulfilled. ...

When we were on the plane coming into Raleigh, there were rumors that a large crowd had gathered. Somebody suggested we land on an outer runway and sneak away so we wouldn't have to deal with the mobs. Uh, just a moment. I had another suggestion. How about if you strap a parachute on me so I can dive into the crowd? What, are you kidding me? We win the ACC's and the guy suggested we sneak away! ...

Then came the NCAA draw. And, sonofagun, if they didn't do it to us again. Did we get Kansas, or Alabama or Seton Hall or some school anybody had ever heard of? No. They came up with Pepperdine, a toothpaste. Those were the jokes, of course. I knew who Pepperdine was. I knew they were an outstanding team. I knew the coach Jim Harrick (who has gone on to resurrect the UCLA program where other "name" guys have failed). I knew they'd be licking their chops for us ... Not to mention, we would have to travel to Corvallis, Oregon to play the first round. We were the ACC champs, and we had to go to the end of the world to play. ...

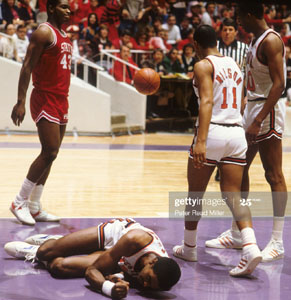

L-R: Ralph Sampson, Lorenzo Charles, George McClain

In truth, it may have been a blessing for us. It gave me a chance to use that wonderful coaching word, "focus." We were going to be able to "focus" on the game because there wasn't much else to "focus" on in Corvallis.

We played awful, missed our first 12 shots, and didn't score for over five minutes. There was a difference from the last time, though. We were a team with a lot of character and with a cause. Most of all, we could play defense. Our defense had kept us in many games, and it did again. Also - a big factor - Pepperdine played as lousy as we did. Friends back East told me that the game was so bad, when we fell behind by eight points late, everybody turned the TV sets off and went to bed. ...

The regulation game ended 47-all after Pepperdine missed two crucial foul shots. In the first overtime, we were down 57-51 with 1:10 to play. To make matters worse, (Sidney) Lowe fouled out with 45 seconds left. At :29 we were behind 59-55. Playing catch-up the whole night, we couldn't quite catch up.

Then we had to foul Dane Suttle, the Waves' best player and an 84% free-throw shooter. That's about the time you tell the bus driver to rev the engines. We're goin' home, Jack; it was nice while it lasted. You don't tell the kids that - you still coach the hell out of the contest. But in the back of your mind, you're thinking of the off-season and how it will be unpacking the woods and irons.

But Suttle missed! George McClain, a sub guard who earlier in the season had been hospitalized for spinal meningitis, had just come in for Lowe. He took the outlet pass from Charles and threw the best pass he would ever throw at State to Bailey roaring down the middle. Bang, a dunk! We fouled immediately. Suttle again. We had to. We wanted him to feel the pressure from that first miss.

The kid missed again. Now we came down with the ball, and Pepperdine fouled Dereck Whittenburg with nine secodns to go. At this point I sent in McQueen, a lefty with the danging arms of an octopus on hormone pills, for a better chance to tap the rebound back out to our guys in case Dereck missed. It was one of those spot decisions that worked out, although it didn't look too snappy at the time. Sure enough, Lo and Co began arguing over who should take the second spot along the lane. I had to holler at Charles to get out of there.

What happened next defied logic, again: Whitt did miss. And McQueen was there for the tap-back, a play made famous, incidentally, by Dean Smith at Carolina. Steal from the best, I always say. But instead of tapping the ball back as I had hoped, Cozell caught the ball and went back up to shoot himself. Oh no! Ohhhh ... yes! The ball bounced over every inch of that rim before falling through.

Pepperdine didn't call time-out; I think they were too shellshocked. They ran it up the side, took a long shot and missed. Double overtime!

We knew we would win now. Pepperdine had gone from high-fiving and celebration on the bench to looking hopelessly lost on the court. Most people believe our run to the NCAA title started in the ACC tournament. But I've always known our "Team of Destiny" tag began with that shot by McQueen against Pepperdine. We won after the second OT, 69-67.

We came out smoking and led 12-1. Remember, we had been ahead of these guys by 16 points back in January, so we knew they could be had. As seemed to happen every game, though, we couldn't stand prosperity. Virginia came back and led 59-51 with about eleven minutes left in the game. ... But there was plenty of time left. Another terrific State comeback - we went ahead by nine points - only enabled us to withstand still another embarrassing drought fromt he foul line. We kept missing free throws, and the clock didn't seem to move.

Our lead was still three points when the littlest player in the game made the biggest play. As Sampson went up for a shot on the inside, Terry Gannon stripped him clean. Ralph had 24 points and 12 rebounds, but Thurl Bailey matched Sampson's points and Lorenzo Charles matched his rebounds for us. Nevertheless, if Sampson had scored there and maybe gotten fouled, the game might have been tied.

As it was, we kept our three-point lead until there was six seconds left, Virginia ball. We had decided to try to keep the ball from Othell Wilson. In fact, we were successful in doing this, and Doug Newburg, not nearly as quick as Wilson, was forced to dribble up the court and make the play. Our pressure was successful; Newburg finally passed off, but the shot came after the buzzer. We were the new ACC champions.

Of course, I cried. Standing there watching the joy on all our players' faces, I couldn't imagine feeling any better or more fulfilled. ...

When we were on the plane coming into Raleigh, there were rumors that a large crowd had gathered. Somebody suggested we land on an outer runway and sneak away so we wouldn't have to deal with the mobs. Uh, just a moment. I had another suggestion. How about if you strap a parachute on me so I can dive into the crowd? What, are you kidding me? We win the ACC's and the guy suggested we sneak away! ...

Then came the NCAA draw. And, sonofagun, if they didn't do it to us again. Did we get Kansas, or Alabama or Seton Hall or some school anybody had ever heard of? No. They came up with Pepperdine, a toothpaste. Those were the jokes, of course. I knew who Pepperdine was. I knew they were an outstanding team. I knew the coach Jim Harrick (who has gone on to resurrect the UCLA program where other "name" guys have failed). I knew they'd be licking their chops for us ... Not to mention, we would have to travel to Corvallis, Oregon to play the first round. We were the ACC champs, and we had to go to the end of the world to play. ...

L-R: Ralph Sampson, Lorenzo Charles, George McClain

We played awful, missed our first 12 shots, and didn't score for over five minutes. There was a difference from the last time, though. We were a team with a lot of character and with a cause. Most of all, we could play defense. Our defense had kept us in many games, and it did again. Also - a big factor - Pepperdine played as lousy as we did. Friends back East told me that the game was so bad, when we fell behind by eight points late, everybody turned the TV sets off and went to bed. ...

The regulation game ended 47-all after Pepperdine missed two crucial foul shots. In the first overtime, we were down 57-51 with 1:10 to play. To make matters worse, (Sidney) Lowe fouled out with 45 seconds left. At :29 we were behind 59-55. Playing catch-up the whole night, we couldn't quite catch up.

Then we had to foul Dane Suttle, the Waves' best player and an 84% free-throw shooter. That's about the time you tell the bus driver to rev the engines. We're goin' home, Jack; it was nice while it lasted. You don't tell the kids that - you still coach the hell out of the contest. But in the back of your mind, you're thinking of the off-season and how it will be unpacking the woods and irons.

But Suttle missed! George McClain, a sub guard who earlier in the season had been hospitalized for spinal meningitis, had just come in for Lowe. He took the outlet pass from Charles and threw the best pass he would ever throw at State to Bailey roaring down the middle. Bang, a dunk! We fouled immediately. Suttle again. We had to. We wanted him to feel the pressure from that first miss.

The kid missed again. Now we came down with the ball, and Pepperdine fouled Dereck Whittenburg with nine secodns to go. At this point I sent in McQueen, a lefty with the danging arms of an octopus on hormone pills, for a better chance to tap the rebound back out to our guys in case Dereck missed. It was one of those spot decisions that worked out, although it didn't look too snappy at the time. Sure enough, Lo and Co began arguing over who should take the second spot along the lane. I had to holler at Charles to get out of there.

What happened next defied logic, again: Whitt did miss. And McQueen was there for the tap-back, a play made famous, incidentally, by Dean Smith at Carolina. Steal from the best, I always say. But instead of tapping the ball back as I had hoped, Cozell caught the ball and went back up to shoot himself. Oh no! Ohhhh ... yes! The ball bounced over every inch of that rim before falling through.

Pepperdine didn't call time-out; I think they were too shellshocked. They ran it up the side, took a long shot and missed. Double overtime!

We knew we would win now. Pepperdine had gone from high-fiving and celebration on the bench to looking hopelessly lost on the court. Most people believe our run to the NCAA title started in the ACC tournament. But I've always known our "Team of Destiny" tag began with that shot by McQueen against Pepperdine. We won after the second OT, 69-67.

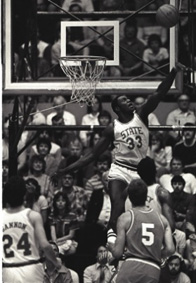

North Carolina State-Pepperdine Action

Continued below ...

Survive and Advance - 4

Valvano: They Gave Me a Lifetime Contract, and Then They Declared Me Dead,

Jim Valvano and Curry Kirkpatrick (1991)

Jim Valvano and Curry Kirkpatrick (1991)

Read Survive and Advance - 1 | Read Survive and Advance - 2

Read Survive and Advance - 3

North Carolina State has reached the 1983 Sweet 16.

Read Survive and Advance - 3

North Carolina State has reached the 1983 Sweet 16.

Before the game I had told Frankie Dascenzo of the Durham Sun that if we got by Pepperdine, we could go all the way and win the whole thing. I really believed that. I honestly felt that if we could just get over that first giant hurdle, we had the type of team to win the championship. In the locker room afterward, I told the guys exactly that. We were in the hands of Fate now. A different guy each night was going to come through for us. ...

We had motivated ourselves for the first NCAA victory. Motivation for our second game came from the opponent, UNLV, when Vegas' star forward Sidney Green said he was "not impressed" with Thurl Bailey. "He didn't show me very much," Green said. You think I didn't Xerox that baby a few times and put it up in the locker room?

It's a cliche, but believe it: We coaches will use anything for an edge, a psych tool, a mind ploy. Bailey would end up just about matching Green - 25 points and nine rebounds to 27 and 10 - and our team played great. The problem was, so did Vegas.

As a team moves through the tournament, the competition obviously becomes better and better. Well, Vegas might have been as talented a team as Houston. I know Jerry Tarkanian's club was the best defensively. Now it became a battle of wills, of execution, of who was the healthiest, deepest, most fit; who had the most nerves and guts.

With over eight minutes to go against Las Vegas, the competition obviously becomes better and better. Well, Vegas might have been as talented a team as Houston. I know Jerry Tarkanian's club was the best defensively. Now it became a battle of wills, of execution, of who was the healthiest, deepest, most fit; who had the most nerves and guts.

With over eight minutes to go againt Las Vegas, we were behind by 12 points. But we'd been behind before; we were used to being behind. I had always told the kids: "Let's just get in position to win." That was a coach's job, to get his team in position. It sounds like a simple thing, but, in fact, a few years later, I read that a successful CEO who was giving a speech to a management seminar told them their jobs were to put their people in position to win. And he told them he had taken that philosophy from the 1983 North Carolina State basketball team!

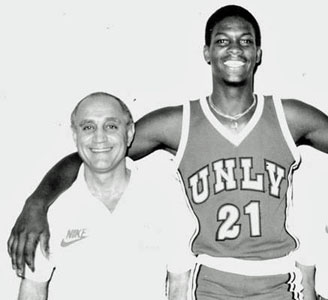

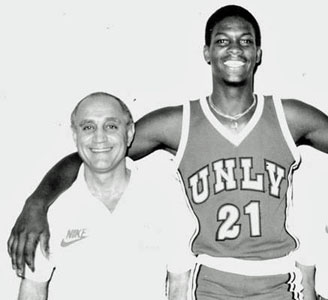

L-R: Thurl Bailey, Jerry Tarkanian and Sidney Green

The score and time always dictated how we positioned ourselves since we always seemed to be behind, that dicated press and foul. Rush the ball up the floor, score, time-out, foul. After we fought back against Vegas to within three points, 67-70; after Bailey hit a jumper with 37 seconds left to make it 69-70; after we called time-out and elected to foul UNLV; after the Rebels' Eldridge (El Cid) Hudson a 68% free-throw shooter, missed - we were in position to win again. This time, we didn't call time-out. Instead, we rushed down the floor, hoping to catch Vegas off guard. I remember what happened next in slow motion. I even remember what we called the play: 5-play. Whittenburg started a drive to the basket with eight seconds to go, but he was cut off and let loose a 20-footer. The ball glanced off the front of the rim, where Bailey was there to tap it back, but that missed too. In the scramble, three Vegas guys should have gotten the ball, but they didn't; they bumbled. Thurl came up with it one more time. Slo-mo. Slo-mo. Off-balance, falling, Thurl tried a banker from the sharp angle ... Good!

Holy God! We rushed the court, thinking the game was over, but Vegas still had three seconds to make something happen. Their last play didn't come close; the shot went over the backboard. We won 71-70.

In the last minutes, Bailey had scored 16 points, most on turn-around jumpers at critical times, including the game-winning ones. I didn't ask Sidney Green if he was impressed.

Following our fourth victory over a Top Five team in the past month, we left Corvallis for Ogden, Utah, and the West Regional, knowing there was something Very Special at hand. We were confident. We were excited. Nobody was going to beat us now. I was so sure of all this, Pam and I took a detour to San Francisco for some serious R and R.

In the first place, because the Regionals were all in the West, we figured it was useless to return to Raleigh, where the players wouldn't be able to get anything done in school, much less on the court. We were getting video tapes from home in the mail, showing one pep rallly after another. We thought it better to stay away from all the pep. ...

In Ogden, all the teams were in the same hotel - Virginia, Boston College, and us - except the home team, Utah. The University of Utah is in Salt Lake City, an hour away from Ogden, but you get the picture. First, we had to play a couple of Western teams on the West Coast. Now we got to play Utah in Utah. Nice, huh? Think we had Rodney Dangerfield's problem?

It's interesting how viewpoints change. In Ogden, all the officials and reporters and hotel and restaurant people remarked upon how loose the Wolfpack players were in comparison to Virginia, whose players seemed tight and nervous. Several years later - try my last season at State - the N.C. State coach took heavy heat for promoting such an "unstructured" environment: a loose, open, laissez-faire program. Back then, the way we did things seemed appealing to folks. Not to mention that it won a national championship. ...

We had motivated ourselves for the first NCAA victory. Motivation for our second game came from the opponent, UNLV, when Vegas' star forward Sidney Green said he was "not impressed" with Thurl Bailey. "He didn't show me very much," Green said. You think I didn't Xerox that baby a few times and put it up in the locker room?

It's a cliche, but believe it: We coaches will use anything for an edge, a psych tool, a mind ploy. Bailey would end up just about matching Green - 25 points and nine rebounds to 27 and 10 - and our team played great. The problem was, so did Vegas.

As a team moves through the tournament, the competition obviously becomes better and better. Well, Vegas might have been as talented a team as Houston. I know Jerry Tarkanian's club was the best defensively. Now it became a battle of wills, of execution, of who was the healthiest, deepest, most fit; who had the most nerves and guts.

With over eight minutes to go against Las Vegas, the competition obviously becomes better and better. Well, Vegas might have been as talented a team as Houston. I know Jerry Tarkanian's club was the best defensively. Now it became a battle of wills, of execution, of who was the healthiest, deepest, most fit; who had the most nerves and guts.

With over eight minutes to go againt Las Vegas, we were behind by 12 points. But we'd been behind before; we were used to being behind. I had always told the kids: "Let's just get in position to win." That was a coach's job, to get his team in position. It sounds like a simple thing, but, in fact, a few years later, I read that a successful CEO who was giving a speech to a management seminar told them their jobs were to put their people in position to win. And he told them he had taken that philosophy from the 1983 North Carolina State basketball team!

L-R: Thurl Bailey, Jerry Tarkanian and Sidney Green

Holy God! We rushed the court, thinking the game was over, but Vegas still had three seconds to make something happen. Their last play didn't come close; the shot went over the backboard. We won 71-70.

In the last minutes, Bailey had scored 16 points, most on turn-around jumpers at critical times, including the game-winning ones. I didn't ask Sidney Green if he was impressed.

Following our fourth victory over a Top Five team in the past month, we left Corvallis for Ogden, Utah, and the West Regional, knowing there was something Very Special at hand. We were confident. We were excited. Nobody was going to beat us now. I was so sure of all this, Pam and I took a detour to San Francisco for some serious R and R.

In the first place, because the Regionals were all in the West, we figured it was useless to return to Raleigh, where the players wouldn't be able to get anything done in school, much less on the court. We were getting video tapes from home in the mail, showing one pep rallly after another. We thought it better to stay away from all the pep. ...

In Ogden, all the teams were in the same hotel - Virginia, Boston College, and us - except the home team, Utah. The University of Utah is in Salt Lake City, an hour away from Ogden, but you get the picture. First, we had to play a couple of Western teams on the West Coast. Now we got to play Utah in Utah. Nice, huh? Think we had Rodney Dangerfield's problem?

It's interesting how viewpoints change. In Ogden, all the officials and reporters and hotel and restaurant people remarked upon how loose the Wolfpack players were in comparison to Virginia, whose players seemed tight and nervous. Several years later - try my last season at State - the N.C. State coach took heavy heat for promoting such an "unstructured" environment: a loose, open, laissez-faire program. Back then, the way we did things seemed appealing to folks. Not to mention that it won a national championship. ...

Continued below ...

Survive and Advance - 5

Valvano: They Gave Me a Lifetime Contract, and Then They Declared Me Dead,

Jim Valvano and Curry Kirkpatrick (1991)

Jim Valvano and Curry Kirkpatrick (1991)

Read Survive and Advance - 1 | Read Survive and Advance - 2

Read Survive and Advance - 3 | Read Survive and Advance - 4

North Carolina State has reached the 1983 NCAA Regional Semifinals.

Read Survive and Advance - 3 | Read Survive and Advance - 4

North Carolina State has reached the 1983 NCAA Regional Semifinals.

Utah had gained the regional with an emotional upset victory over UCLA, and I knew Utes' coach Jerry Pimm would have them prepared. They played very tough defense until we kept moving back further out and taking those three-pointers we had learned to shoot in the ACC. They didn't count for three points now - and Pimm told his team at halftime: "Don't worry. They can't keep shooting that way" (i.e. 59%). He was right. In the second half, we shot 78.9% and won 75-56. Virginia beat Boston College in the other game, so the West Regional final would be a repeat of the ACC final.