CONTENTS

Duluth

Saves the NFL - I

Duluth

Saves the NFL - II

Harry Wismer

Weeb Gets the Colts Job

Weeb vs. The Horse

Replacing a Legend Isn't Easy

Did Anybody Bring a Ball?

The Ultimatum Bowl

Take That, Brother-in-Law!

Curly Bails Out Green Bay

Football

Stories – I

Football Stories –

II

Football

Stories – III

Football Stories – IV

Football Stories – V

Football Stories – VI

Football Stories - VII

Football Stories - IX

Football Stories - X

Football

Magazine

Golden Rankings Home

Top

of Page |

Interesting

Football Stories– VIII

The

inspiration for the movie "Leatherheads" (released

in April 2008) was the Duluth

Eskimos, a National Football League team in

1926-7. The league president stated that the Duluth

franchise had "saved the NFL." Let's explain how that

came about.

Duluth

MN entered the NFL in 1923 with a team called the Kelleys

because the Duluth-Kelley Hardware Store bought the uniforms.

The franchise was a cooperative owned by 11 players who split

expenses and profits, if there were any. The coach was the 23-year-old

QB (actually blocking back in the single wing formation of the

time), Joey Sternaman, who had played at Illinois.

At a time when there was no centralized scheduling in the league,

each franchise made its own slate. The other 19 teams were not

excited about playing Duluth either home or

away. So the Kelleys

played only seven games, winning the first four (Akron

Pros, Minneapolis Marines

twice, and Hammond Pros)

and losing the last three (Milwaukee Badgers,

Chicago Cardinals,

and Green Bay Packers).

Three of the first four were played in Duluth but, as the season

entered November, the last three were on the road instead of

in their home city close to the Canadian border. The Canton

Bulldogs won the league with an 11-0-1 record.

Duluth finished

7th.

The

Kelleys returned

for the 18-team 1924 season with WB Dewey Scanlon

(age 25) as coach. The team could schedule only six games, two

at home (victories over the Packers

and the winless Kenosha Maroons)

and four on the road (two victories over winless Minneapolis,

a loss at Green Bay,

and a season-ending win on November 23 at the Rock

Island Independents). Duluth

rose to fourth place as the Cleveland

Bulldogs had the best winning percentage (7-1-1).

When the player-owners lost $44 each for the year, they sold

the franchise for $1 to their team secretary, Ole Haugsrud.

Bobby "Rube" Marshall |

In

1925, Duluth

played only three games, losing them all (Kansas

City Cowboys and Rock

Island at home and the Chicago

Cardinals on the road). The Kelleys

didn't finish last in the 20-team league because the Rochester

Jeffersons and Milwaukee

Badgers went 0-6, the Dayton

Triangles 0-7, and the Columbus

Tigers 0-9. The 1925 Duluth team included

Bobby "Rube" Marshall, the second

black man to play in the NFL. He was 45 that year, which

makes him one of only six players in NFL history 45 or older.

He put washboards under his jersey to protect his ribs.

He is a member of the College

Football Hall of Fame.

The

Duluth franchise teetered on the brink of extinction. It

needed a shot in the arm. That's exactly what Ole

Haugsrud would give both his team and the league.

Continued below ...

|

|

Duluth Saves the NFL - II

Ernie Nevers

|

Ole

Haugsrud, who had taken over the Duluth

team in 1925, craved a big star to draw

fans. As luck would have it, Ole went

to Superior (WI) High School with Ernie

Nevers, the All-American FB from Stanford.

The league encouraged Ole to pursue

Nevers because Red Grange,

who had drawn big crowds wherever he played in the NFL

in 1925, was organizing the American

Football League along with his manager,

C. C. Pyle. C. C.

also wanted Nevers for his league.

Ole

outbid Pyle and signed Ernie.

Haugsrud renamed the team the Duluth

Eskimos and agreed that they would play

all their league games on the road in exchange

for a chunk of each gate. The result was "the longest

road trip in sports history" – 17,000 miles.

The vagabonds played 29 games, including 16 exhibitions,

from October through February. To save laundry money,

the players took two post-game showers, the first one

with the uniforms on.

After

two warmup games at home, the Eskimos

embarked on their NFL schedule, finishing with a 6-5-3 record

and a profit. In addition to Nevers, another

Duluth star

was TB Johnny

McNally (who played professionally as "Johnny

Blood"), supposedly the inspiration for George

Clooney's character in "Leatherheads."

|

Meanwhile,

the eight-team AFL struggled, with only Grange's

New York Yankees

a reliable draw. Teams started folding after only four games.

The Philadelphia Quakers

went down in history as the winner of the only championship

of the short-lived AFL. Their 8-2 record put them ahead of

the 10-5 Yankees.

Because Duluth

countered the AFL threat by signing Nevers

and playing on the road, NFL president Joe Carr

credited Haugsrud with saving the league.

The

NFL absorbed the Yankees

for the 1927 season. With Grange back in

the fold, owners were not as anxious to play Duluth.

The Eskimos

fell to 1-8 with all games again on the road. When Nevers

decided to return to Stanford

as an assistant coach to Pop Warner, the

NFL gave Haugsrud permission to suspend the

franchise for 1928. Then in 1929, when he sold his franchise

for less than he thought it was worth, the NFL sent him a

letter vowing that if the league ever returned to Minnesota,

Haugsrud would be given the first option

at being the owner.

In

1961, when the Minnesota Vikings

entered the NFL as an expansion team, Haugsrud

cashed in on the league's promise. He was given the opportunity

to purchase 10% of the team for $60,000.

Nevers

returned to the NFL and played three years (1929-31) with

the St. Louis Cardinals.

|

This story concerns legendary radio announcer Harry Wismer (1913-1967). After his college football career at Florida and Michigan State ended with a severe knee injury, Harry began broadcasting MSU sports. He eventually gained wider exposure as the voice of the Washington Redskins. (His first game was the Redskins' infamous 73-0 pasting in the 1940 championship game.) Harry called the NFL championship on television in 1948 and 1950 for ABC and 1951-53 for the DuMont network. He also announced Notre Dame games nationwide for many years.

Wismer also gained fame as the narrator of the weekly football highlights in newsreels and on television. Ahead of his time in some ways, Harry packaged a abbreviated version of each Irish game that was shown the next day on the DuMoint television network. When DuMont went under several years later, CBS successfully marketed exactly the same package on Sunday mornings during the 1960s and 1970s.

Wismer's broadcasting met mixed reviews. He gained a reputation as an enormous ego and name dropper. Critics claimed he was more concerned with reciting the names of celebrities in attendance rather than the action of the field. They also charged that he included some of his friends in the crowd when they were not actually present.

One Wismer story concerns an Army game he supposedly announced during which Doc Blanchard ran 70 yards for a touchdown. Unfortunately, Wismer called Glenn Davis as the ball carrier. When he realized his mistake, he told the audience Davis lateralled the ball to Blanchard, who continued into the end zone. One problem with this story is that it is also credited to Bill Stern, Wismer's chief competitor in national sports broadcasting.

Harry Wismer (far right back row) with the original AFL owners in October 1959 Harry satisfied his ambition to own a pro team when the American Football League began play in 1960. However, his New York Titans drew just 114,682 fans in their inaugural season in the Polo Grounds. When this number dwindled to a mere 36,161 in 1962, the other owners loaned Harry money to keep the team afloat in the #1 media market. The league arranged the sale of the team in 1963 to Sonny Werblin who renamed it the Jets and moved to the new Shea Stadium.

Listen to Wismer narrate Notre Dame football highlights

|

This is the first of a multi-part story that traces Weeb Ewbank's odyssey that led him to coach the Baltimore Colts to the NFL championship in 1958. First of all, Weeb's unusual name resulted from his little brother's inability to pronounce "Wilbur." With that out of the way, let's start the journey.

Weeb Ewbank

|

At Miami University (OH), the "Cradle of Coaches," Weeb played QB on the same team as Paul Brown, establishing a connection that would eventually give Ewbanks his big chance. While in college, Weeb also played semipro baseball under an assumed name in order to preserve his amateur status and football eligibility.

After coaching many years in high school, Weeb joined Brown during World War II as his football assistant at Great Lakes Naval Station in Chicago. After the war, they went their separate ways for several years – Weeb as head coach at Washington University in St. Louis – but Ewbanks rejoined Brown with the Cleveland Browns in 1949, the fourth and last season of the All-American Football Conference, which the Browns won every year. In 1950, they joined the NFL and won the championship but lost the title game in '51. Both men were students of the game and strongly believed in study and preparation. Weeb helped Paul create the passing offense that revolutionized pro football. |

Paul Brown with his QB Otto Graham

|

Let's shift attention now to Baltimore, where Carroll Rosenbloom bought the hapless New York Yankees in order to move the team to his hometown for the 1954 season. Carroll hired his old friend Don Kellett as GM. Kellett's first job, of course, was to find a head coach. A stroke of luck helped Weeb land the position. One of his college players, Charley Winner, who had also married the coach's daughter, scouted for the Browns and found himself on a plane with Kellett after the Blue-Gray game in Montgomery. With every team in the NFL trying to install Brown's program, Kellett responded favorably when Winner told him that Weeb was interested in being a head coach. When Kellett hired Ewbanks, Winner came along as his right-hand man.

Continued below ...

|

This is the second part of a story that traces Weeb Ewbank's odyssey that led him to coach the Baltimore Colts to the NFL championship in 1958. If you haven't already, read Part I.

Weeb Ewbank |

At the end of his first training camp with the Colts, Ewbank assembled the veterans on the team and shocked them by asking for a vote on which of the six newcomers should fill the last two spots on the roster. After an uncomfortable silence, DB Bert Rechichar finally named someone he thought should be cut. A few others then expressed opinions. Finally the real leaders spoke up and refused to do the coach's job for him. DT Art Donovan, who developed an affection for Weeb, still referred to him as "That weasel bastard" because he put them through the futile exercise. Weeb never pulled that stunt again.

Like his mentor, Paul Brown, Weeb had a mean streak. It is a trait that even the players who came to admire Ewbank think he could have done without. The chief target of his ire was fun-loving FB Alan Ameche. "The Horse" got on Weeb's bad side from the start because the coach didn't think he was focused enough on football. Ameche was late for practice and wouldn't get his ankles taped before games with the rest of the team. However, on Sunday, no one was more competitive than Ameche. Despite making the Pro Bowl four times, he remained the butt of Weeb's ridicule. As a result, Alan retired after only six seasons, not because of injury but because he disliked playing for Ewbank. |

Alan Ameche

Alan Ameche

|

Weeb was smart enough to include on his roster two players who redefined what it meant to be professional football players: E Raymond Berry and QB Johnny Unitas. Each of them merits a future article in his own right.

Reference: The Best Game Ever by Mark Bowden

|

Replacing a Legend Isn't Easy

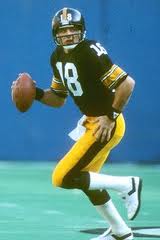

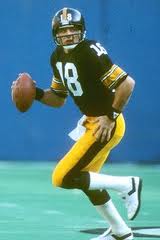

Aaron Rodgers, beware! Replacing a legendary QB (Brett Favre in your case) is risky business. Consider, for example, the case of Cliff Stoudt, backup to Terry Bradshaw in Pittsburgh for six seasons. Unfortunately for Stoudt, those six seasons included four Super Bowl titles for the Black and Gold.

When Cliff became the starter in 1983, he threw 21 INTs and only 12 TDs. He "was booed so relentlessly in Three Rivers Stadium you'd have thought he'd canceled Christmas." At least he had a sense of humor. "I tried to commit suicide, but the bullet got intercepted."

Stoudt signed with the Birmingham Stallions of the United States Football League after the '83 season. However, that didn't end his ordeal in Pittsburgh. As luck would have it, the Stallions' third game of 1984 was in Three Rivers Stadium against the Pittsburgh Maulers. The only sellout in the Maulers' one year of operation turned out, many wearing BOO STOUDT shirts and buttons. Fans threw snowballs, beer cans, and other debris. Stoudt was hit on the helmet three times. Play had to be stopped when an official standing too close got nailed by a full can of beer. Cliff did have the satisfaction of winning the game, 30-18.

He led Birmingham to a 14-4 record and the Southern Division title. Jim Mora's Philadelphia Stars defeated them for the Eastern Conference championship. In the USFL's final season (1985), Stoudt QBed a 13-5 team. He then returned to the NFL in a backup role for four more seasons with the St. Louis/Phoenix Cardinals and the Miami Dolphins.

In 2004, the Steelers invited the 1979 Super Bowl team for a 25th anniversary celebration in conjunction with a game against the Eagles. Stoudt felt much trepidation as he waited to be introduced. But apparently time does heal all wounds. The fans cheered him along with all the others. So contrary to Thomas Wolfe, Cliff could go home again.

|

Cliff Stoudt, Steelers

Cliff Stoudt, Birmingham Stallions

|

Reference: "Welcome to The Club," Chris Ballard, Sports Illustrated, July 7, 2008

|

Did Anybody Bring a Ball?

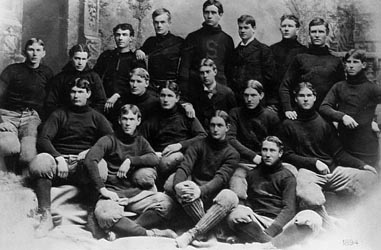

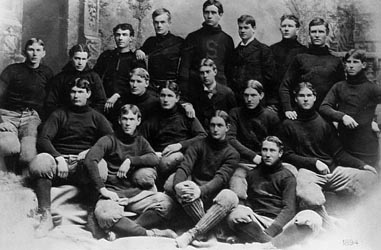

California and Stanford began their annual football game in 1892, shortly after Leland Stanford endowed his university.

- The second game in the series was organized by the Stanford student manager, Herbert Hoover - yes, the future president. He collected $30,000 in gate receipts from the 20,000 fans who turned out at the Haight Street Grounds, a baseball park in San Francisco. However, he overlooked one detail of game preparation. No one brought a football! The owner of a sporting goods store went to his shop and returned with a ball so that the game could begin after an hour delay. The Oakland Tribune used the phrase "The Big Game" to describe the contest and the monitor stuck. Stanford upset the favored Golden Bears 14-10.

|

Future president Herbert Hoover is fourth from the right in the top row of this picture of the 1894 Stanford team. Hoover was student-manager. |

- The symbol of the rivalry has been the Big Axe, whose origin has conflicting explanations. What is known is that a Stanford yell leader named Billy Erb used the 15-inch axe to decapitate a stuffed bear in blue-and-gold apparel during a baseball game. When Cal won, its fans grabbed the Axe, cut off its long handle, and kept it like a victory trophy. It would be brought out for football and baseball rallies at Berkeley until 1930 when Stanford students stole it back fair and square.

- Both schools agreed to make the Axe the annual victory trophy in 1933. That same year the axe tradition influenced Stanford to adopt a new nickname for its teams. To that point, the Palo Alto squads had been dubbed the Cardinals because of the predominant color of their uniforms. Stanford officials decided to call the school teams the Indians. Apparently they liked the way that area cartoonists had represent Stanford teams as an American Indian wielding an axe to trap and skin the Cal Bear. Of course, in that era, no one protested that the monicker was offensive to Native Americans. However, by 1972, opposition to the nickname had surged to the point that the school went back to a monicker close to the original and became the Stanford Cardinal - not the bird so as not to offend the ornithologists but rather a tree endemic to Northern California. In fact, the Stanford logo has the tree entwined in it. Remember, folks - we're talking about California here, and specifically the San Francisco area.

References: Football Feuds: The Greatest College Football Rivalries, Ken Rappoport & Barry Wilner

|

The Ultimatum Bowl

Darrell Mudra

Frank Kush

|

The annual Arizona - Arizona State clash is known as the "Duel in the Desert." The 1968 game ratcheted up the enmity between the schools to an even greater pitch.

Arizona was 8-1, and Arizona State was 7-2. Both were in the Western Athletic Conference at that time. The winner of the game was promised a berth in the Sun Bowl in El Paso TX. Or so ASU and its fans believed. But that's not what Wildcat coach Darrell Mudra thought. He gave the Sun Bowl committee an ultimatum: Take Arizona win or lose or we won't go to the Sun Bowl even if we defeat our rival. The committee caved in and invited Arizona the Tuesday before the game.

You can guess what happened on the field that Saturday night in Tucson. Frank Kush's Sun Devils clobbered Arizona 30-7 in what was quickly dubbed the "Ultimatum Bowl." FB Art Malone scored on ASU's first offensive play and then again in the first seven minutes as the Devils scored the first three times they had the ball. With the best rushing D in the nation, ASU manhandled the Wildcat O line, not allowing a single yard on the ground.

Since there weren't nearly as many bowl games in 1968 as there are today, Kush's team sat home during the holidays and watched Arizona's embarrassment continue in El Paso where they lost to Auburn 34-10.

Mudra left Arizona after the bowl game to coach Western Illinois. Then in 1974, he took over at Florida State. After going 4-18 in two seasons, he turned the Seminoles over to Bobby Bowden.

Something good did come out of the 1968 fiasco for Arizona State after all, though. Community leaders in Phoenix began working to establish a bowl game that ASU could host if they weren't invited anywhere else. The first Fiesta Bowl was played in 1971 with ASU defeating Florida State 45-38. Today, of course, the Fiesta is one of the most lucrative bowls, with a solid spot in the BCS rotation.

Reference: Football Feuds: The Greatest College Football Rivalries, Ken Rappoport & Barry Wilner

|

|

Take That, Brother-in-Law!

Dan McGugin

|

Dan McGugin hailed from Iowa, graduated from Drake, and attended the Michigan Law School. With the loose eligibility rules of the era, Dan played on Fielding "Hurry Up" Yost's "Point-a-Minute" teams. Dan was also Yost's brother-in-law. (They married sisters.) While pursuing a legal career in the off-season, Dan became the head coach at Vanderbilt in 1904 at age 24. He more than any other man is credited with raising the level of Southern football. Until his retirement in 1934, Dan's Commodores went 193-52-19. He originated the onside kick, developed the use of guards as interferers, and was one of many to develop the passing game.

Here are two stories about Dan getting the goat of his brother-in-law. |

- In 1922, another of Yost's Wolverine powerhouses came to Nashville for the dedication of Dudley Field, the first stadium in the South built exclusively for football. Before the game, McGugin addressed his players in a Southern accent. He spoke of how the grandfathers of the invading Yankees from Ann Arbor had killed the grandfathers of the Vandy players during the Civil War. The inspired 'Dores held mighty Michigan to a scoreless tie. Afterwards, Yost expressed his outrage. "That McGugin and his phony accent! Before he came to Vanderbilt, he'd never been farther South than Toledo!" Dan had also neglected to tell his players that his own father had been an officer in the Union army.

- Once McGugin and Yost shared a drawing room during a train trip to the West Coast for a coaches' convention. Fielding spent the time polishing the talk he was to deliver as main speaker at the closing banquet. He asked Dan to give his advice. McGugin listened and told Yost it was a fine speech. Yost kept rehearsing the talk across the continent until he had it letter perfect. At the banquet, the toastmaster told the audience that, before introducing the main speaker, "I am sure you'd like to hear a word or two from our past president, Dan McGugin of Vanderbilt." McGugin accepted the invitation and delivered Yost's speech!

|

Fielding Yost

|

Reference: "Sports of the Times," Arthur Daley, New York Times, May 8, 1956

|

Curly Bails Out Green Bay

Contrary to popular belief, the Green Bay Packers were not one of the original teams in the American Professional Football Association when it formed in 1920. However, they did join the second season.

Curly Lambeau |

- John Clair of the Acme Packing Company in Green Bay WI was awarded one of the eight new franchises as the APFL expanded to 22 teams. The league extended from New York in the East to Minneapolis in the West and from Green Bay in the North to Louisville in the South.

- As his coach, Clair chose 23-year old Earl "Curly" Lambeau. An outstanding athlete at Green Bay East High School, Curly had returned to his hometown after one year on Knute Rockne's varsity at Notre Dame. In 1919, he had organized a team for the Indian Packing Company where he worked. When Clair's company bought out Indian Packing, Lambeau persuaded the new owner to enter his team in the APFA.

- The Packers compiled a record of 3-2-1 that season when each team made its own schedule. The Akron Pros played 12 games while the Tonawanda Kardex (more on them in the future) played only one.

- Green Bay's original colors were navy and gold, not the green they've sported since 1959.

- On June 22, 1922, the APFL changed its name to the National Football League and dropped from 22 to 18 franchises.

- For awhile, it looked like the Packers would not be one of the 18. They had admitted to using college players on their squad and been fined by the league.

- On January 28, 1922, Clair withdrew from the league. However, Lambeau wouldn't let the team die. Promising to obey league rules, he put up $50 to buy back the franchise.

- 1922 was a tough year for the Packers. Bad weather and poor attendance caused Lambeau to go broke. He appealed to the local merchants, who arranged a $2,500 loan and set up a public nonprofit corporation to operate the team so that it could stay in the NFL.

- The Packers remain to this day the NFL's only publicly owned franchise. Eventually, they named their stadium Lambeau Field.

|

|

|