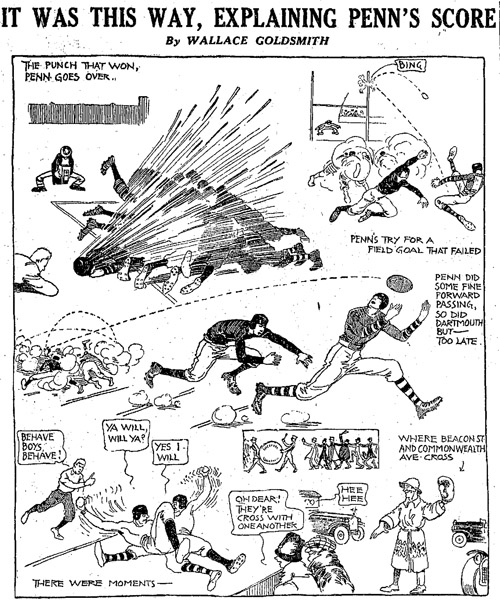

Penn finally started the winning drive from its 35. Webb:

Trailing 7-0 after the extra point, Dartmouth's chances seemed bleak since the Green had not threatened the Penn goal. However, the Hanover Boys were not willing to concede the victory. After receiving the kickoff, the Green unleashed a passing attack of their own.

Dartmouth finished the season with a 5-3 record while Penn went 9-2.  Sunday Boston Globe 11/18/17

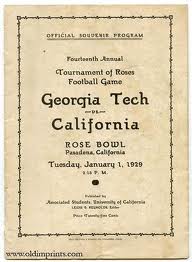

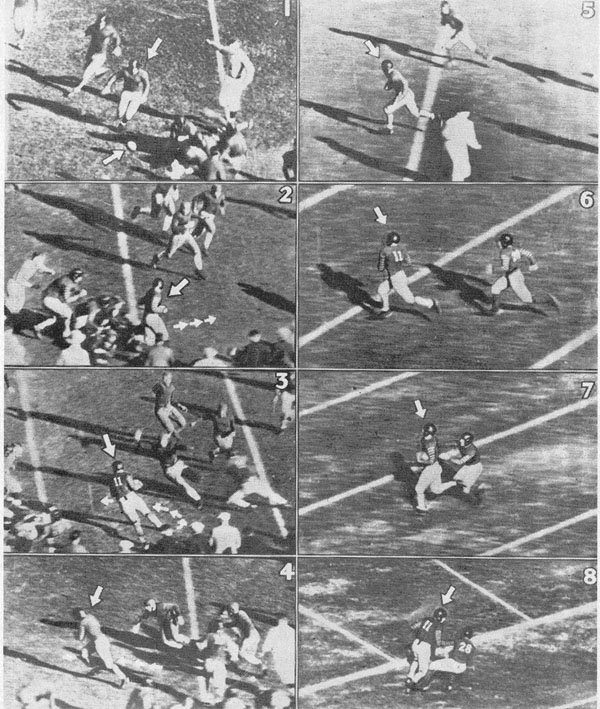

Riegels' run gallery Two outcomes were a direct result of Roy's error.

"Wrong Way" Riegels became a national celebrity.

Roy earned accolades for his performance on the gridiron.

Roy continued in football after graduation.

The Rose Bowl Web site calls the Wrong Way run "the most famous play in Rose Bowl history" and credits it with gaining the annual game "national notoriety that never existed in such scope previously." ESPN voted the play #26 in its "100 Moments That Have Defined College Football." Many would argue that it should rank higher.

|

CONTENTS

Memorable Football Games Index

|