|

Interesting

Football Stories– VII

Norm Carlson

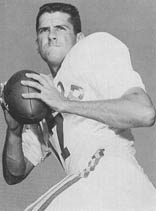

Steve Spurrier

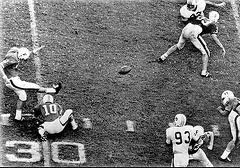

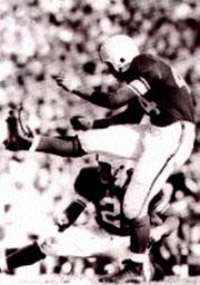

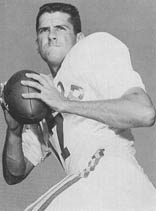

Spurrier Kicks Winning FG vs Auburn

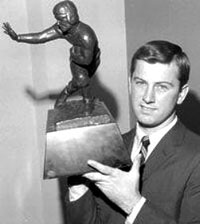

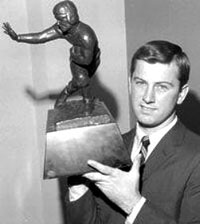

Spurrier with Heisman

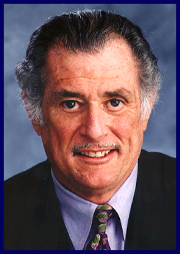

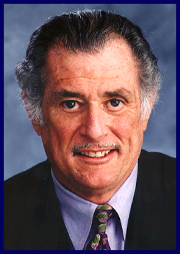

Coach Steve Spurrier

Tim Tebow

Top of Page

|

It's possible to pinpoint the first time that a sports publicist spearheaded a successful campaign for his school's hero for the Heisman Trophy.

Norm Carlson started working at the Florida athletic department in 1963 after working for a few years as a sportswriter.

- His staff consisted of a part-time secretary and a student assistant.

- One of his first actions was to change the atmosphere in college football press boxes to make them more professional. He enforced the rule, "No rooting in the press box."

- That was particularly hard to do at the annual Florida-Georgia cocktail party at Jacksonville's Gator Bowl. Every year, numerous boosters and nonmedia types filled the press box, yelling and cheering and detracting from the working atmosphere.

- Carlson stationed security guards at the press box door, instructing them to admit only those with press passes. Norm recalled: One guy did bully his way in. He was a very, very big Gator booster. He knew the president of the university and also Coach [Ray] Graves. He had a pal with him, and he was carrying a fifth of whiskey.

- When Carlson had them removed, the booster cried, I'll have your job by Monday! You'll never work here again!

Nevertheless, Norm was still on the job when QB Steve Spurrier entered his senior year in 1966.

- Carlson changed Steve's number from 16 to 11. Spurrier: Norm liked same-digit numbers like 11 and 22 and so forth. He thought it was easier to promote guys with those types of numbers, that people could remember them better. The next thing I know, I show up to practice one day, and I have number 11. That was Norm's doing.

- Norm thought the Gators' sensational QB was Heisman material. But, with no Florida games on TV that year (in an era when the NCAA controlled all telecasts and severely rationed them), he decided he had to take matters into his own hands to make Heisman voters appreciate Steve's accomplishments.

- He put together a film of Spurrier's best plays from the 1965 season and mailed it to 500 TV stations all over the country.

- Each Sunday, Carlson phoned sportswriters and influential Heisman voters, recounting Steve's accomplishments the day before as QB, punter, and kicker.

- When he obtained a list of Heisman voters, Norm was shocked to learn how few there were in the South. (A blatant example of prejudice that was matched by the paucity of AP poll participants in Dixie.) So he led a campaign for more Heisman voter registration in the South and urged those who were registered to be sure to vote.

- Carlson: I had always wanted to know why Johnny Majors [of Tennessee] didn't win the Heisman Torphy in 1958, and he had a phenomenal year. Yet it was Paul Hornung on a 2-8 Notre Dame team who won.

Carlson received unexpected help from an influential source.

- Midway through the season, he received a call from Governor Haydon Burns, who asked what he could do to help the Spurrier-for-Heisman campaign.

- Norm sugggested sending out another batch of films featuring Steve's highlights from the current season.

- Carlson recalls that Governor Burns called the Tourism Department and said, "I want these Spurrier clips sent to all these places." So the state of Florida, through the Tourism Department, sent out another 500 film clips in the middle of the year.

Spurrier greatly aided the quest by his heroics in the Auburn game.

- A record crowd of 60,511 packed Florida Field, including many national media representatives in the press box.

- Coach Graves recalled: I had heard before the game that Steve told some of the players during breakfast that he dreamed he kicked a field goal to beat Auburn.

- Spurrier: It was a frustrating game because we were really a lot better than them. But they ran a kickoff back for a touchdown and got a fumble in midair and the guy went 91y. I think they had about 125y of offense and we had 400-something, and yet it was 27-all in the fourth quarter.

- Steve completed 27-of-40 for 259y, a TD, and no INT.

- Late in Q4, the Gators drove to the Tiger 24. Graves called timeout with the intention of sending in regular FG kicker Wayne Barfield. But Steve went to Ray, pointed to himself, and said, Let me have a shot at this one.

- On the Auburn sideline, coaches yelled, Watch for the fake! when Spurrier lined up to kick. But head coach Shug Jordan supposedly told his assistants, You better hope its a fake, because if Steve Spurrier tries this field goal, he will make it in this situation.

- Spurrier: I laced my shoe on and kicked it through. No doubt. I kicked it right in the middle of the goalposts. It was sort of ironic, because I hit it right on the seam, which was exactly facing me.

The dramatic boot sealed the Heisman for the Florida QB.

- Spurrier received 1,679 points in the voting to 816 for pre-season favorite Bob Griese, the Purdue QB.

- Beano Cook, ABC college football commentator at the time, recalls: To win the Heisman Trophy without being on national TV is like winning the presidential election without winning California. Without Norm, Spurrier doesn't win the Heisman Trophy. Spurrier should at least give one of the arms to Norm, and I think Spurrier knows that.

- In those days, the announcement was not carried on live TV. In fact, the ceremony was held two weeks later with just the winner coming to New York's Downtown Athletic Club.

- After receiving the trophy, Steve called the UF president forward. Dr. Reitz, come up. This trophy doesn't belong to me. This belongs to the University of Florida. Spurrier handed the precious hardware to the shocked president. I want to present this trophy to the University of Florida where students and alumni can see if if they so desire.

- When the Gator faithful heard about Steve's gesture, they started a fund-raising campaign to provide money to the Athletic Club for another trophy that Steve could keep.

- The NYDAC did provided another trophy and, ever after, has issued two statues each year, one for the athlete and one for his school.

Carlson continued at Florida until his retirement in 2006.

- He got to enjoy the glory years when Spurrier returned to his alma mater in 1990 as head coach. In fact, Steve made Norm his right-hand man and confidant, the guy who introduced the coach at Gator gatherings.

- The Gators won the SEC six times and the national championship once during Steve's twelve years at the helm.

- Carlson and Spurrier wrote a book together about the Gators' 1991 SEC championship season.

- Norm served as Florida's athletic historian when Tim Tebow became the second Gator to take home the Heisman in 2007.

Reference: Stadium Stories: Florida Gators, Peter Kerasotis, 2005

|

Ken Stockdale

|

Ken Stockdale was a freshman QB for Baylor in 1963.

- At that time, freshmen were not eligible for varsity competition.

- So schools operated freshmen teams that played their own schedule.

- The freshmen teams had their own nicknames that were offshoots of the varsity's monicker, such as "Baby Tigers" or Texas "Shorthorns."

Baylor's freshman coach was Milburn A. "Catfish" Smith, the quintessential cantankerous but ultimately lovable coach.

- Catfish had been a successful player, high school coach in both basketball and football, and college coach in East Texas.

- He was eventually inducted into four halls of fame, including the Texas Sports Hall of Fame.

As the Baby Bears prepared to face their Texas counterparts, Smith pulled out all the stops to motivate the team. Let Stockdale tell the story.

Right before the game, Catfish started crying, telling us that he was about to die and that we needed to win this game for "the old man." True, he had had part of his stomach removed, and true, no one knew exactly what the final results of that surgery would be. You would have thought he had one foot already in the grave and that he might not be able to make it through the game alive. It was a true "win one for the Gipper" story, and we tore out of the dressing room ready to play.

Since he would alternate quarters with Terry Southall, Stockdale's job to start the game was to stand beside the coach and chart the plays.

I was more concerned about Catfish's health than I was about the actual game. What if he went down beside me? What could I do to help him? My worry would be short-lived.

- Early in the game, Baylor ran a screen pass to flankerback Paul Becton, a 9.7 sprinter, who lined up right in front of the Baylor bench.

- Southall faked a handoff and threw to Becton, who eluded the first defender and set sail down the sideline.

Then I realized Catfish wasn't beside me. He was running down the sideline matching Becton stride for stride. He actually beat Paul to the EZ and was the first to maul him as we celebrated the TD. I thought Catfish might have a heart attack or pass out, but he wasn't even winded! So much for the "one foot in the grave" theory. ... We went on to win that game 21-17, and Catfish was in rare form for several weeks.

Catfish lived 31 more years. Stockdale had a productive career, first as a backup and then as the starter under C for head coach John Bridgers.

|

"I didn't like the way you treated Coach Bryant."

This is a football story that spills over into basketball. Long-time SI writer Frank Deford reports that "Bear Bryant was the coach who got me into the most trouble, if inadvertently."

Frank Deford

|

|

Bear Bryant |

If he didn't know already, Frank learned that day, in his own words, that "coaches, like sportswriters, are a tight fraternity. They always call each other Coach, as if it were a military rank or religious office."

"Confessions of a Sportswriter," Frank Deford, Sports Illustrated, 3/29/10

Bert Rechichar, Colts

|

Alex Hawkins, himself one of the most colorful players in NFL history, tells this story about his Baltimore Colts teammate Bert Rechichar.

When Hawkins reported to the Colts in 1959, Rechichar introduced himself. "I'm 44. What's your name?" Bert had a cigar stuck in his mouth and kept his blind eye closed. "He was meaner than hell at high noon," said Hawkins of the former Tennessee Vol.

In 1953, his rookie year and the Colts' debut in the NFL (after the hapless Dallas Texans were transferred), Rechichar practiced kicking long FGs even though he wasn't the club's regular FG kicker. In the season opener against the Bears, the Colts found themselves at the Chicago 49 with four seconds left in the first half. Bert had started toward the locker room when an assistant coach wondered if Bert could kick a FG from there. So Rechichar went on the field without bothering to attach his chin strap and lined a 56-yarder through the uprights. Until Tom Dempsey's 63-yarder in 1970, it was the NFL record. That same game, the DB/LB ran back an interception 39 yards for a TD in the Colts 13-9 upset of George Halas' squad before 23,715 at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore. In his ten-year career, strong>Bert made 31 of 89 FG attempts.

Bert carried all his money with him, leading the other players to call him the "First National Bank of Rechichar." No one knew where he lived. When Coach Weeb Ewbank

finally released him, Bert asked Hawkins to give him a lift to pick up his belongings. Alex jumped at the chance to finally learn where Bert lived. Instead, Rechichar directed him to half a dozen back alleys and side streets where he picked up a pair of pants in this building, a jacket in that one, a couple of shirts here, a pair of shoes there. After an hour of this, Bert said, "O.K., that's it." Hawkins concludes: "Would you say that Bert Rechichar was a totally sane man?"

|

After leading Washington State to a 7-3 record in 1951 – the school's best performance since 1932 – 33-year old Forrest Evashevski found himself a hot commodity in his profession. Not one, but two, Big Ten schools came a-calling. He chose the Iowa Hawkeyes over the Indiana Hoosiers. He was rewarded with a handsome $15,000 salary. ( Indiana hired Bernie Crimmins, who compiled a 13-32 record in six seasons.)

Forrest inherited a program that had not won as many as six games since 1939 and not achieved seven wins since 1922.

- He immediately expanded recruiting to other areas.

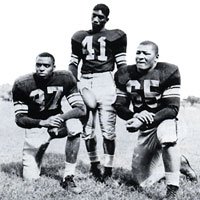

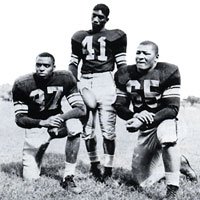

- One group of freshmen was dubbed the Steubenville Trio: Eddie Vincent

(#37), Frank Gilliam (41), and Calvin Jones (65), from the same high school in Ohio.

- Ohio State's second-year coach, Woody Hayes, offered a scholarship to only Jones.

- So Cal's two buddies accepted Evashevski's offer.

- That fall, when Vincent and Gilliam drove to Jones' house to say goodbye on their way to Iowa City, their pal surprised them by jumping in with them.

- Cal's switch prompted a Big Ten investigation that uncovered no impropriety. Jones told Commissioner Tug Wilson his reason for staying in Iowa: "They

treated me like a white man, and I like it here."

|

The Steubenville Trio

|

Since freshmen were ineligible for varsity competition in those days, the Trio had to watch as Evy's first team went 2-7.

- But they contributed to a 5-3-1 record the next season.

- Jones showed why OSU had offered him a scholarship as he was named an All-American guard three years in a row, a first for a Hawkeye player. In his senior year (1955), he was named team captain and became the first African-American to win the Outland Trophy, given annually to the nation's best interior lineman.

With NFL opportunities still limited for black players, Jones played one year with the Winnipeg Blue Bombers of the Canadian Football League.

- Tragically, he died in a plane crash the day after playing in the first CFL All Star game in Vancouver. He had overslept and missed his original flight earlier that morning.

- He had planned to meet the other two members of the Trio at the Rose Bowl where the Hawkeyes defeated Oregon State 35-19.

- Gilliam, who missed the '55 season with a broken leg, was playing his final year.

That game, the first bowl game in school history, marked the culmination of Evashevski's rebuilding project.

- The 1956 team won the Big Ten title, compiling an 8-1 regular season record (the only loss coming at home to Michigan, 17-14).

- The Hawks dedicated their 35-19 Rose Bowl victory to Cal. His number became only the second one to be retired by the school. The other was that of Niles Kinnick, for whom the Iowa stadium was named after his death in World War II.

- Jones was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1980.

The Hawkeyes returned to Pasadena after the 1958 season and defeated California, 38-12.

Forrest retired two years later to become athletic director. His nine-year record at Iowa was 52-27-4. He truly put Hawkeye football on the map.

Military Academy Hi-Jinks

Football rivalries have sported lots of hi-jinks. You'd think the Army- Navy

tradition would rise above such nonsense since both are service academies. NOT! Here are some examples.

- In 1894, President Grover Cleveland held a cabinet meeting to discuss the Army-Navy football game. At the contest a few months earlier, brawls had broken out in the stands, and a rear admiral and a retired general nearly staged a duel. Fearing for the reputation of the two institutions, Cleveland cancelled the game. In 1899, President William McKinley restored the rivalry.

- Just before the 1971 game, a limo with presidential flags flying drove into Philadelphia's Municipal Stadium. Since rumors

had circulated that President Nixon would attend, the crowd buzzed, and the West Point cadets stood at attention and saluted as the car drove past them. It ended up on the Navy

side where the door was opened ... and the Navy goat emerged!

- In 1973, three Navy cheerleaders were posted to the roof of the stadium to coordinate the Midshipmen's entrance and an initial cheer for TV. Army cadets jumped the cheerleaders and proceeded to give the Midshipmen some confusing signals. The officers on the field finally restored order but only after the Cadet corps got a good laugh.

- In 1975, future presidential candidate H. Ross Perot, Naval Academy '53, sneaked into the West Point chapel the night before, and serenaded the cadets with a few tunes from the belfry: "Anchors Aweigh," "The Marine Hymn," and "Sailing, Sailing." Some cadets captured Perot and turned him over to military police.

- The most common prank is the kidnapping of the opponent's mascot – the Navy

goat or the Army mule.

- A group of Midshipmen disguised as Army cadets sneaked into West Point and escaped with four mules after tying up the handlers. The beasts were the featured attraction at Navy's pre-game pep rally.

- Before the 1953 clash, Cadets kidnapped Billy XIV. However, West Point sent the animal back to Annapolis, expressing "deep regret." The colonel who commanded the military escort issued this statement upon arrival: "They say in the Army there are four general classes of officers: aides, aviators, asses, or adjutants. I am an adjutant at West Point, have been playing aide to a goat all day, and feel like a bit of an ass."

- 1990: West Point Cadets stole a goat from the Naval Academy Dairy, but they took the wrong one. The goat they captured wasn't the official mascot, and the joke was on the Cadets - he didn't get the job because he was mean and smelled much worse than most goats.

- A month before the 1995 game, a group of seniors from West Point staged a pre-dawn raid on the Naval Academy dairy farm in Maryland and kidnapped Bill the Goat XXVI, XXVIII and XXIX. The Pentagon was notified, and the three goats were returned under a policy forged by flag officers of the Army and Navy that stipulates that the "kidnapping of cadets, midshipmen or mascots will not be tolerated."

The Navy goat and Army mule at the 1923 game. |

Longhorns-Aggies

Texas has two hated rivals: Oklahoma

and Texas A&M. Until the Big 12 was formed in 1996, the Sooners were the yearly non-conference rival while A&M was Southwest Conference Enemy #1. From 1996-2011, all three schools resided in the Big 12 South. Let's look at the Texas-Texas A&M rivalry.

- "UT students view Aggies as simple-minded farm boys who were thrilled to wear soldier suits," an observer once said. And "boys" they all were until the first female students were admitted to Aggieland in 1963.

- A&M is actually the older school. It was founded in 1870, 13 years before UT.

- About 100 miles apart, both schools are among the largest in the nation: 49,500 in Austin and 46,500 in College Station.

- The two schools first played football against each other in 1894. Texas holds a huge lead in the series: 73-36-5 (through 2007). That's the most victories for UT

vs. any opponent, edging Baylor (71-22-4) by two.

Texas A&M

Texas A&M – Texas 1902

- Texas boasts four national championships: 1960, 1963, 1970, and 2005. A&M claims one: 1939 when they crushed UT 20-0 as part of an 11-0 season under Homer Norton.

- Some interesting facts about the series:

- A&M failed to score in five straight games from 1898-1902, although the first 1902 game (in San Antonio) was a scoreless tie. When the teams played again that season at Texas, A&M won 12-0.

- From 1900-1909, every game was played in Austin (except the first of two in 1902 and the first of two in 1909, which were both played in Houston). The only contests in 1910 and 1911 took place in Houston.

- A&M won only one of the first 17 contests. However, new coach Charley Moran, hired specifically to beat Texas, defeated the Longhorns three times in a row, including twice in his first year, 1909.

- UT charged that Moran achieved his success with illegal players, leading to a suspension of the series from 1912-1914.

- In 1915, a group of Aggies sneaked onto the UT campus and branded the Texas steer with the score of their 13-0 victory that season. Some Texas students supposedly used a running iron to turn the numbers into the word BEVO, which has been the name of the UT mascot ever since.

The most famous tradition of the series is the Bonfire, which started in 1909 when Aggie students ignited a pile of junk just to keep warm. But the idea caught on as a way to symbolize A&M's "burning desire to beat t.u." (lowercase initials intentional by the Aggies). Texas also lit pregame bonfires for many years, leading to a series of pranks by both sides.

- 1949: Four Aggie students drove onto the Texas campus in broad daylight and poured gasoline on the Longhorn woodpile and tried to preignite it. However, the flames jumped

to the car and burned two of the Aggies. (Were they burnt orange?) Undeterred, they tried again the next day and were successful.

- Texas students piloted a private plane over the A&M campus and dropped incendiary bombs into the woodpile.

- In 1999, tragedy struck as the huge Aggie woodpile collapsed in the early morning hours, burying students trying to finish the structure. 12 died and 27 were injured. University officials suspended the event. So students have done the bonfire off-campus in recent years.

Some memorable games in the series:

- 1908: The first of two games scheduled between the rivals that year took place in Houston as part of a carnival called No-Tsu-Oh (Houston spelled backward). Ahead 14-0 at the half, Texas students paraded onto the field with broomsticks to mock A&M's military tradition. Aggie cadets stormed the field. When the brawl ended, UT completed a 24-8 victory.

- 1915: Aggie "Rip" Collins punted 23 times for an amazing 1,026 yards, an average of 45 yards per punt. The reason he punted so much was that A&M coach E. H. Harlan felt his best chance lay in keeping UT bottled up in its own end of the field. When the Longhorn safety man mishandled several punts, the Aggies capitalized for a 13-0 upset in the two schools' first year in the new Southwest Conference.

- 1920: The Aggies hadn't been scored on in two years (17 games) under new coach Dana X. Bible but lost to Texas 7-3 in a battle of unbeatens. Bible later coached at Texas.

- 1922: Despite a 22-3-1 record in three seasons, UT coach Berry Whitaker was fired after losing to A&M 14-7.

- 1933: Both coaches – Madison Bell at A&M and UT's Clyde Littlefield – were fired after the game ended 10-10.

- 1940: Texas A&M was striving to complete its second straight undefeated season and earn its first trip to the Rose Bowl. The Longhorns gleefully spoiled both dreams with a 7-0 victory in Austin.

|

Homer Norton

Charley Moran, who was also a MLB umpire.

Rip Collins, who pitched for the Detroit Tigers.

E. H. Harlan

Dana X. Bible, who coached both Texas and A&M

|

The Amazing Run of Plainfield Teachers College

Morris Newburger

|

Morris Newburger was a Wall Street stock broker in 1941 and a sports fan who enjoyed Laurel and Hardy and Marx Brothers movies and pulling pranks.

|

During the next few weeks, Newburger phoned in additional Plainfield victories (over equally nonexistent schools) to the New York papers while his friend, radio broadcaster Alexander "Bink" Dannenbaum, did the same in Philadelphia. (The two sometimes forgot to agree on the opponent and score but no matter.)

- In addition, Newburger sent out a news release on Plainfield Teachers Athletic

Association stationery listing Jerry Croyden as the school's publicity director.

- Coach Ralph (Hurry-Up) Hoblitzel employed his unique "W Formation" in which the ends faced the backs.

- The star of the team was Chinese-Hawaiian RB Johnny Chung, nicknamed the Celestial Comet. Chung gained energy by eating a bowl of wild rice at halftime.

- Completing buying the story, New York Post sportswriter Herbert Allan wrote in his "College Grapevine" column: John Chung has accounted for 57 of the 98 points scored by his unbeaten and untied team in four starts. If the Jerseyans don't watch out, he may pop up in Chiang Kaishek's offensive department one of these days.

- Croyden also phoned reporters to alert them to Plainfield's undefeated season and probable invitation to the Blackboard Bowl in Atlantic City.

- This led to notes appearing in midweek football columns about the team and its star RB. (Chung was supposedly the name of a worker at a Chinese laundry that Newburger patronized.)

- Reporters were even contacting Croyden asking for complete lineups of the game. He filled the Plainfield lineup with names of people he liked and gave the opponents names of people he didn't like. Morris installed himself at LT for one game and at QB for another.

Meanwhile, Newburger's broker friends joined in the fun.

- They created linemen and assistant coaches as well as cheerleaders.

- Morris's Philly friends began wearing Plainfield Teachers sweatshirts.

- Newburger even composed a fight song for his imaginary school based on a Cole Porter hit.

You're the top,

You're a double feature.

You're the top,

You're a Plainfield teacher.

You're a football star, a backfield czar, unsung.

You're a galloping ghost,

You're just the most,

You're Johnny Chung.

You're not me,

You're a teacher's idol.

You're the key,

To a Plainfield title.

I'm a little man, a timid fan, a flop.

But if Johnny, I'm the bottom,

You're the top.

But the plans for an undefeated season were derailed unexpectedly.

Illustration accompanying

1968 New York Times article

on the occasion of New-

burger's death. No way such a

politically incorrect illustration

would run in the Times today.

|

With the "team" gaining notoriety as it prepared for its final two games with Appalachian Tech and Harmony, a suspicious Herald-Tribune reporter went to Plainfield NJ to find the college.

- A free-lance financial writer, one of Newburger's Wall Street circle to whom he bragged about the hoax, didn't find his stunt amusing and revealed the duplicity to Caswell Adams of the New York Herald Tribune. Adams's editor, Irving Marsh, called the Board of Education in Plainfield NJ and found that no Plainfield Teachers College existed.

- After confronting Newburger, who confessed, Adams wrote a story in the Herald-Tribune that included this parody sung to the tune of Cornell's "Far above Cayuga's Waters":

Far above New Jersey's swamplands

Plainfield Teachers' spires

Mark a phantom, phony college

That got on the wires.

Perfect record made on paper,

Imaginary team!

Hail to thee, our ghostly college,

Product of a dream!

- Jerry Croyden issued his final press release: Due to flunkings in the midterm examinations, Plainfield Teachers has been forced to call off its last two scheduled games.

- The Philadelphia Record, which had been brought in on the hoax, rued the loss of Plainfield Teachers. It published an unsigned item titled Football Casualty.

[The paper] regrets the passing (of Plainfield Teachers). The place had possibilities. We don't see why exposure of the gag should have to end the team's career. It should keep playing the rest of the season. We want to know how it made out with the now-cancelled games. And we want to know if the "Celestial Comet" could make All-American.

Several weeks after the end of Plainfield's "season," the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor changed everyone's life.

|

|

If All Else Fails, Try Voodoo

Alabama and Auburn first met on the gridiron in 1892. Auburn won 32-22 before 450 fans at Lakeview Baseball Park in Birmingham. The teams continued to meet yearly, either in Montgomery, the largest city close to Auburn, or Birmingham in Bama's backyard, until 1907. However, a disagreement over who would officiate and how much expense money would be paid to the players caused cancellation of the 1908 contest. The schools never met again until 1948 and then only because the state legislature strongly urged the two presidents to resolve their differences.

On December 4, 1948, the Red Drew's Crimson Tide routed the Plainsmen of Earl Brown 55-0 at Legion Field in Birmingham. Before the game, Bull Connor, the Birmingham police commissioner who 15 years later would turn water cannons and attack dogs on African-American civil rights marchers, met with student leaders of both schools to warn them that no shenanigans before, during, or after the game would be tolerated in his Iron City.

It didn't take long for Auburn to gain revenge. In 1949, star TB Travis Tidwell, who had suffered a fractured vertebrae in the '48 game, led the 1-4-3 Tigers to a 14-7 lead before a "packed house" of 44,000 "in a wild, fight-marred game"

on a cold, clear afternoon. Then Bama scored with 1:20 left, and their star QB Eddie Salem lined up to kick the tying point. Tidwell explained later: "I played safety on defense, and we made eye contact. I had my hand straight out in front of me, twitching my fingers kind of voodoo-like. He saw that and had a strange look on his face. He missed the extra point. I've always said that I put my voodoo on him."

When Auburn went 0-10 in 1950, including another shellacking by the Tide 34-0, Brown was replaced by Shug Jordan. Then, after Alabama fell on very hard times - including five straight losses to Auburn, it turned to alumnus Paul Bryant to resurrect its fortunes. Thus began the era when the Iron Bowl became one of the most important and heated rivalries in the nation.

|

Earl Brown

Travis Tidwell

|

Reference: Football Feuds: The Greatest College Football Rivalries, Ken Rappoport & Barry Wilner

Did Bryant Really Wrestle a Bear?

Paul Bryant (lower right in white)

Paul Bryant (lower right in white) |

Anyone who knows the least bit about college football knows that Paul "Bear" Bryant got his nickname because he wrestled a bear in his youth. Is this a sports myth or did it really happen? The answer is "yes, it happened" but there is some dispute about details. What follows is the most likely scenario of the versions that have circulated.

|

- The publicity worked. The theater's 200 seats were filled that night for the contest.

- The bear was no grizzly. By all accounts, it was rather scraggly and was muzzled for the match. It may have been declawed or had covering over its paws.

- At any rate, Bryant decided to employ a strategy that he would deplore when opposing coaches tried it on the gridiron. He would run out the clock and settle for a tie. With little mat experience, he planned to wrestle the bear as he would wrestle a man.

- When the bear reared up, Paul charged and pulled it down, holding him on the floor.

- The bear's owner wanted action for his money. So he cried, "Let him up!" in Paul's ear.

- The animal worked itself free, but Bryant tried the same tactic again. They rolled and thrashed around the stage for another few seconds.

- In the tussle, the bear's muzzle came off. A few women screamed, and a few seconds later, Paul felt a burning sensation sensation on his ear and realized he had been bitten. Blood was running down his neck.

- "I was being eaten alive! I jumped off that stage and nearly killed myself hitting the empty front seats with my shins." (The first rows had been cleared to keep spectators further from the action.)

- Years later, Paul still enjoyed pulling up his pants legs to display the marks where he had crashed into the chairs.

The final chapter of the story should surprise no one. When Bear had been patched up, he went to claim the $3 he was owed only to find that the owner and bear had skipped town. However, the nickname "Bear" probably earned Bryant way more than $3 the rest of his life.

Reference: The Last Coach: A Life of Paul "Bear" Bryant, Allen Barra

|

CONTENTS

Birth of Heisman Hype

Win One for the Old Man

"I didn't like the way you treated Coach Bryant"

Bert

Rechichar

Evy

Transforms Iowa

Military

Academy Hi-Jinks

Longhorns-Aggies

The

Amazing Run of Plainfield Teachers College

If All Else Fails, Try Voodoo

Did Bryant Really Wrestle a Bear?

Football

Stories – I

Football Stories –

II

Football

Stories – III

Football Stories – IV

Football Stories – V

Football Stories – VI

Football Stories – VIII

Football Stories - IX

Football Stories - X

Football

Magazine

Golden Rankings Home

Top

of Page |