CONTENTS

Walter Camp and the Birth of American Football - I

Walter Camp and the Birth of American Football - II

Walter Camp and the Birth of American Football - III

Seven Years of College Eligibility

"Best Quick-Kicking Team in History"

Football

Stories – I

Football

Stories – II

Football Stories – III

Football Stories – IV

Football

Stories – V

Football Stories – VII

Football Stories – VIII

Football Stories - IX

Football Stories - X

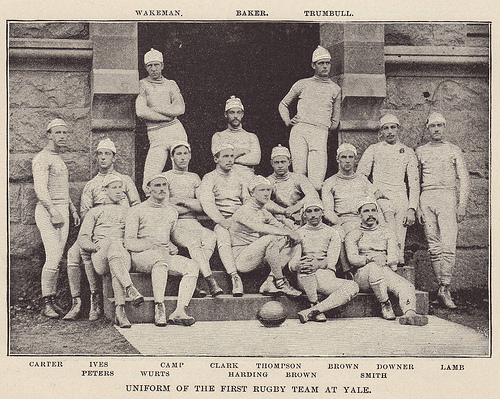

Walter Camp has been dubbed the "Father of American Football." He played the largest role in the evolution of the primitive rugby-like game that existed when he played at Yale into the distinctively American sport that had spread across the continent when he died in 1925.

We pick up the story in 1875, Camp's senior year of high school in New Haven.

- Even though he was not enrolled in Yale yet, he attended the Elis' football practices as a member of the "scrub team" whose purpose was to scrimmage the varsity.

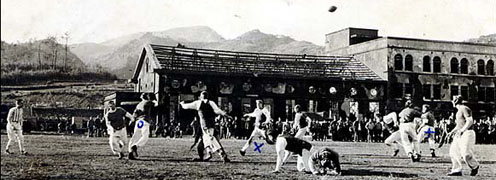

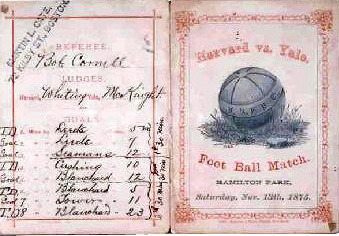

- Camp helped line the field at Hamilton Park where Yale and Harvard met that year for the first time in a football game.

An immediate problem was that Harvard played a different version of "football" from that played by Yale.

- Yale preferred a form of football that resembled soccer.

- Harvard played a version that, like rugby, allowed players to run with the ball.

- The Yale captain agreed to try the Harvard rules.

- The Crimson won the game 4-0. Despite the loss, the Yale players decided they preferred their rivals' brand of football.

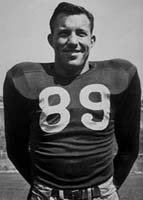

Walter Camp 1878-9 |

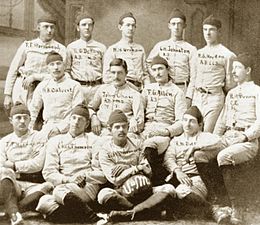

1875 Yale-Harvard Program |

The next year, Camp became one of only two freshmen to make the Yale varsity football team.

- He was elected captain of the freshman team. In that capacity, he actually served as player-coach since there were no formal coaches.

- The 1876 Yale squad won all three of its games - against Harvard, Princeton, and Columbia - without allowing a single goal.

- Camp played for all four years of his undergraduate education, then continued for two more while in medical school. He served as captain-coach after his freshman year. The Eli won 25 and lost only one with four ties during his six years at Yale.

- The game obviously captured his imagination. He carried a notebook in which he created formation and sketched plays.

- Walter started a seventh season on the team but a knee injury ended his playing career. He went on to become the first great coach of the sport.

Returning to 1876, Princeton invited Columbia, Harvard, and Yale to send representatives to a conference on November 26.

- The purpose of the meeting was to agree on a standard set of rules so that captains wouldn't have to meet before the game to negotiate how the contest would be conducted. The result was the Intercollegiate Football Association.

- The field was set at 140y x 70y.

- A neutral referee would run each game, freeing the captains from having to settle disputes.

- The meeting established the scoring rules and set the number of players on a side at 15.

Camp began attending the annual meetings of the Association in 1878. He usually came armed with proposals to improve the sport.

Continued below ...

Reference: The Big Scrum: How Teddy Roosevelt Saved Football, John J. Miller (2011)

|

||||||

|

Walter Camp continued to experiment with the rules of football in 1883. The rules committee he headed changed the scoring system inherited from rugby, which had simply counted goals as one point.

The following year, the committe tinkered some more.

The committee members must have liked this system because it lasted 14 years. One influential person who didn't like the system or anything else about football was Harvard president Charles Eliot.

Eliot appointed an athletic committee in 1882 to oversee and regulate sports at the nation's oldest university.

The ban didn't last long.

The facts didn't support that face-saving statement.

Despite the violence - or, more probably, because of it - football gained in popularity.

As a result, Camp's rules committee stuck with the status quo until 1894, when public furor broke out again. To be continued ... Reference: The Big Scrum: How Teddy Roosevelt Saved Football, John J. Miller (2011) |

When

World War II ended (and he no longer needed to attend West

Point to avoid the draft), Barney wanted

to return to Ole Miss, but Coach Blaik wouldn't release him. So he intentionally flunked out of the Academy.

The Gloster MS native is considered one of the finest ends in SEC history.

He shares the Ole Miss record for receptions in a game

with 13 against Chattanooga

in 1947, the year he teamed with QB Charlie Conerly to lead the Rebels to their first SEC championship.

He was selected to Ole Miss' All-Century team in 1992.

Barney was drafted by the New York Giants in 1945 but stayed in college. Then in 1948 he was taken by the New York Yankees of the All-American Football Conference and played seven pro seasons with the Yanks and then the Dallas Texans, Baltimore Colts, and New York Giants of the NFL. Two of his brothers, Buster and Ray, also played at Ole Miss where the three earned a total of 50 letters. A campus thoroughfare is named Poole Drive. Barney died in 2005 in Jackson, where he had managed Memorial Stadium for many years. |

|

This

story could just as easily appear on the Baseball Page since it involves

both a football great and a famous baseball figure.

The football hero is Howard "Hopalong" Cassady who won the 1955 Heisman Trophy at Ohio State. In high school, the 5'10" 170-pound Cassady was a star RB/DB in football – as you would expect – but also an excellent shortstop. He played both sports for Ohio State, leading the baseball team in HRs in 1955 and in SBs in 1956. He chose to go pro in football and played seven seasons for the Detroit Lions. While in the ROTC during his freshman year at OSU, Cassady met an Air Force lieutenant at the base near Columbus. That lieutenant was George Steinbrenner, who also coached high school football and basketball in Columbus and then was an assistant football coach at Northwestern (1955) and Purdue (1956). Steinbrenner recalls what happened when the Wildcatsplayed at Ohio State. Before the game, Hopalong "came over to shake my hand and I said, 'Get outta here ya little (bleep)! You're on the other team!' First thing I know he fumbles at his 3, picks up the ball in his end zone and is suddenly running by me at the 50! He was a great, great player." Steinbrenner left coaching to help his father in the American Shipbuilding Co., where he made the fortune that allowed him to buy the Yankees in 1973. One of the salesman who sold steel to the company was Hopalong. In 1976, George hired Cassady as a conditioning coach for spring training. Hopalong brought the newest fitness innovation, the Nautilus machine, to training camp. The trimmer Yanks immediately reached the World Series in 1976, 1977, and 1978, winning the last two. Cassady also scouted for Steinbrenner and served as first-base coach for the AAA Columbus Clippers for awhile. He continues to work at the spring training camp to this day.

|

|

Mississippi

State University began as Mississippi A&M,

then became Mississippi State College in 1932, which

is when the nickname "Maroons" took root.

However, reporters lauded the team's "bulldog" style of play,

which led to the school's official athletic symbol. In 1935, coach Ralph

Sasse obtained a bulldog named Ptolemy in Memphis to become

the team mascot. His energized squad immediately downed mighty Alabama 20-7.

Ptolemy's brother became "Bully I" after Sasse's team upset Army 13-7 at West Point that same year. Bully earned lasting fame, however, by the way he died. After the beloved mascot was killed by a bus in 1939, the campus went into mourning for days as Bully lay in state in a glass coffin. The Maroon Band and three ROTC battalions led 2,500 mourners in a procession to Scott Field for Bully's burial under the home team bench at the 50-yard line. Even Life magazine covered the event. Bully I's successors have also been buried on campus, although not always in the football stadium. |

|

Does

the name Tommy Blake mean anything to you? Many will be watching the 2008 NFL Draft to see if and when Tommy's name is called.

A year ago, the only argument was how high in the first round Blake would go. The 6'3" DE from TCU had led the Mountain West Conference with 16 1/2 tackles for loss in 2006. As a result, he was a 2007 preseason All-American and expected to compete with Virginia's Chris Long to be the first DE drafted. Now there is a strong possibility that Blake will not be drafted at all. What happened? He was not injured in the conventional sense of the word. Instead "college football's mystery man" was the victim of mental illness. Halfway through the Horned Frogs' fall camp last August, the fifth-year senior was the best player on the field even though he wasn't in top shape yet, having passed on many of the "unofficial" off-season workouts led by his fellow seniors. "He was still 255 pounds of greased lightning coming off the edge." NFL scouts attended practice to scope him out. But suddenly Blake, known as one of the most pleasant Frogs, began showing signs of anger. He argued back to coaches and then walked off the practice field. His sister drove him home to Aransas Pass TX. Coach Gary Patterson flew the 370 miles and convinced him to return a few days later. But matters only got worse. Blake "continued to exhibit disturbing, often combative behavior." His road roommate said, "He was not the old Tommy." No one, including Blake himself, understood what was happening. TCU held him out of the season opener because of a "medical condition." He played – poorly – in the next three games (which Patterson admits was a mistake on his part) and then was given a medical leave of absence. Since privacy laws prevented TCU officials from disclosing his condition, rumors swirled: drug abuse, steroid use, legal troubles, even a story that he was entering the Baptist ministry. He returned for the final four games overweight and apathetic. In December, he gave his first interview with a reporter in which he admitted, "I kind of lost track of football for a little bit" but gave no details about what had happened. Finally, in late January, at the urging of his agent, Blake publicly admitted that he was being treated for depression and social anxiety disorder. He played in the East-West Shrine Game in Houston where he was grilled about his condition both by reporters and by some NFL representatives. He weighed 287, 30 pounds heavier than scouts think he should be. He is working to lose weight for the combine workouts. One NFL scout says, "I wouldn't touch Tommy Blake. I don't know how you can justify bringing a player in who has mental instability." It will be interesting to see if any NFL team takes a chance on him either in the draft or as a free agent. (Follow-up: Blake was not drafted.) Reference: "Living on the Edge," Sporting News 2/18/2008 |

|

An

item in the Hayward (CA) Review (among other newspapers) on

December 29, 1945

The Marines occupied Nagasaki in September 1945, six weeks after the atomic bomb detonated over the city and shortly after the Japanese Surrender on the battleship Missouri. As Christmas approached, the men were homesick. So the commanding officer, Major General LeRoy Hunt, suggested a football game to raise morale. Rather than thinking it insensitive, the men regarded the game as a celebration of the end of the war and the consequent saving of lives that would have been lost on both sides if the U.S. had invaded Japan. Two former football stars, Bertelli (who won the Heisman Trophy in 1943) and Osmanski, were enlisted to organize the teams. A surprising number of the Marines had played football at Temple, Michigan State, Washington, UCLA, Texas Tech, and other colleges while still more had high school experience. By trading with officers on Navy ships, equipment was gathered to fashion goal posts and bleachers on Atomic Athletic Field #2, one of two recreation areas cleared from the debris. However, the condition of the field presented a problem. Although no one knew enough about the effects of the bomb to fear radiation poisoning (else the Marines would never have been sent to Nagasaki in the first place), the field was littered with shards of glass. So the captains agreed to play two-hand touch below the belt instead of tackle football. Fifteen yards would be required for a first down instead of the usual ten. Bertelli and Osmanski also secretly agreed to do everything in their power to make the final result a tie in order to keep peace in the units.

Despite snow flurries, 2,000 filled the bleachers to capacity for the game. The division band played "On Wisconsin." Bertelli tossed two TD passes to lead Nagasaki to a 13-0 lead at the half. However, Isahaya retaliated in the second half on two scoring runs by Osmanski. With the game tied 13-13, George Halas' former star couldn't resist the temptation to shuck the pre-game pact and kick the PAT for a 14-13 victory. Reference:

"In 1946, a search for relief on a desolate Nagasaki field,"

|

Bobby Jackson

|

When Bear Bryant went "home to Mama" to coach his alma mater, he took over a program that had won four games in the last 36.

In conjunction with the visit to Starkville, Bear recalled the story of Red Blount, a longtime member of the Alabama athletic board, who played an important role in bringing Bryant to Alabama.

Finally, the Tide got the break Bryant was looking for.

The score held into Q3.

The next week brought more of the same against Georgia in Tuscaloosa.

What happened next set off what Bear called "the biggest fight I ever saw."

|

Paul "Bear" Bryant with John Underwood (1974)

Above the Noise of the Crowd: Thirty years behind the Alabama microphone, John Forney (1986)

Top of Page