|

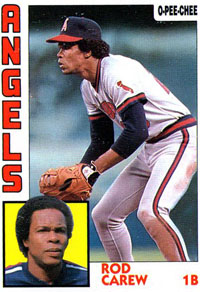

Just because Rod Carew has hit .300 nine years in a row, people have developed the notion that this man is something special.

It even is being said that Mr. Carew has won a niche for himself in the Hall of Fame.

When he makes his appearance at that shrine, the proclamation should be read that Carew was an uncommon batsman, but that he was being admitted for the damndest achievement in baseball.

By the summer of '77, he had stolen home 16 times.

You may try to minimize this accomplishment, but to those artists especially gifted at stealing bases, the theft of home 16 times is the Pulitzer Prize, the Nobel Prize, the Congressional Medal and the Triple Crown, all in one.

Stealing home is so inconceivable to a formidable base runner such as Davey Lopes that he refuses to acknowledge it is, even for professionals.

"That's for amateurs," says Lopes, with the disdain of a London jewel thief for one who swipes hubcaps. "I've never tried to steal home. Your only chance is if the pitcher's mind is in the next county."

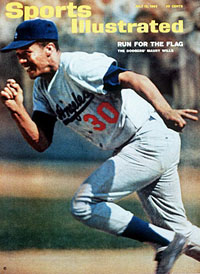

In his distinguished career as a base gonif, Maury Wills attempted the theft of home only once, admitting candidly he was restrained by the fear of failing.

You won't find Lou Brock or Joe Morgan working that area, and even Mickey Rivers, rated a scattergun runner, as opposed to a scientist, won't try it very often.

But Carew not only has the will to try but is excited by the action.

"I started in 1969 when Billy Martin was managing the Twins," he recalls. "Runs were coming hard for us, and Billy told me not to be afraid to take a chance."

Since those attempting the theft of hom do so unfailingly while the pitch is on the way to the plate, or while the pitcher is in motion, Carew began a study of those at the mound.

"I watched the way they held the ball in their glove, the way they held it in their hand and how they wound up," he says. "I tried to calculate how much of a walking lead I could take on them. If it was big enough, I would surprise them by breaking for the plate."

Incredibly, Carew stole home seven times in 1969. From that point forward, he has been under surveillance as much as known family heads of the Cosa Nostra.

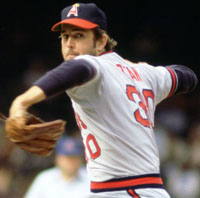

"I can't think of anything more humiliating than losing a ball game to a guy who steals home on you," says Nolan Ryan the California pitcher. "It happened to me one time against Kansas City. I had a 2-and-2 count on the hitter, and Amos Otis broke from third. The pitch was a ball and he slid in safe. I felt like a nickel."

Since Ryan comes from Alvin, Texas, and since it is well established that a stranger running a shell game can work a small town only once, Nolan is duly wary.

"When I see Carew on third," says Nolan, "I'll usually work from a stretch an we'll have our third baseman hold him close. You give up something when you do this. I lose the advantage of a windup and we leave a bigger hole at third for the batter."

But Nolan and other pitchers are quite willing to make that sacrifice when they think of the alternative.

"Does your batter know when you are going to break for home?" Carew was asked.

"I flash the sign," he answered. "But hitters don't always pick it up. Harmon Killebrew, for instance, missed it one time and swung as I headed for the plate. It gave me a terrible fright. I thought he was going to kill me."

It was a similar experience that discouraged Wills, the terror expanding when Frank Howard, the hitter, took an awesome swing and hit a liner foul that missed Maury by inches. Trembling visibly, Wills related afterward that the ball zooming past his head looked as big as a casaba, and Howard's bat took on the dimensions of the Eiffel Tower.

Carew confides he never has felt a fear of failing, and the record gives him little reason for feeling otherwise. In 19 attempts at this colossal undertaking, he has been caught only three times.

"When I start to feel I can't make it," says Rod, "I'll probably stop."

That, of course, will be a very happy day for pitchers, who may begrudge him four hits in every 10 at bats, but not nearly as much as they begrudge him the theft of home. As Ryan says, this is the ultimate in degradation, and pitchers who are burned usually enter a monastery. |

Davey Lopes  Maury Wills  Nolan Ryan  Amos Otis |

Harmon's First HR | Feller's Debut | Heads-Up Triple Play | Game Stopped by a Fight | Old Horse Helps Old Hoss | Infield Fly Confusion | Tiger Farewell to Mickey | Germany Calls His Story | I'm Not Just Your Manager Now | What a Way to Lose Where'd Everybody Go? | Strange Steal of Home | "Dilatory Tactics Lose for Mackmen"

Strange Injuries - I | Unassisted Triple Play "The Wildest Afternoon" | Nice Story But It Didn't Happen | Earthquake Opened the Door for Doerr | Cal and Rex | Don't Let the Fire Stop You

Bits of Baseball Lore - III

Left-Handed Catcher |

Ugly Uniforms But Illegal? |

18-inning Shutout |

Traded for an Announcer |

Last Browns Game |

Nothing But Slow Curves |

Score That 1-2-7-6-7 |

Zeke Steals Home |

Steve Bartman: Cub Enemy #1 |

Even the Greats Lost Money

Bits of Baseball Lore - IV

Gates Gets Caught |

An Unusual Doubleheader |

Terry's Side of the Story |

Lineup Shenanigans |

Baseball's Anthem | Braves' Dissension |

Ruth Starts Fast |

Babe's First Season |

How Catfish Got His Name |

Wanted: Catcher

Strange Contracts |

K Almost Becomes HR

Bits of Baseball Lore - V

Sutcliffe Steals Second |

Babe Brains Ty

Manager Incites Riot |

Two More Babe Stories |

Punish Rowdy Richard |

"Kelly Now Catching for Boston" |

Notable Nicknames |

"The Meal Ticket" Joins the Giants |

McGraw Admired His "Beauty" |

34+ Run Games |

Rogell Didn't Dare Leave the Lineup |

Did You See It, Bill?

Bits of Baseball Lore - VI

"The Brat" Screws Up | Ballplayers And Their Bats | Red Sox Rally | Fatal Attraction | Blame It on Early | Know the Rules! | Shield Your Eyes, Dear | Batting Order Oddities |

Historic Day at Polo Grounds | In LF, What's His Name

Bits of Baseball Lore - VII

Odd Contract Request | Fastest Game Ever | Don't Throw Your Glove at Ball | Bug Invasions | Rapid Robert Returns | Dom vs Joe Connie Mack - Thief? | Row on a Ball Field |

Astrodome Oddities | Ducky Is Shot Down

Bits of Baseball Lore - VIII

You're Blaming Wrong Man | Spitter Sign Enos's Mad Dash | "Kill the Ump!" | Costly Clouts | Unusual Plays | Rookie Outcast | Red Was Too Honest

Bits of Baseball Lore - IX

Fell Asleep Leading Off 2B | Surprise Series At-Bat | McGraw's Big Blunder | He Should Eat Barbecue Every Night | Yankee-Red Sox Clashes | Lou's Lost Hits | Two HRs and They Pinch-Hit for Me! | If All Else Fails, Try Humor 58 Innings in Three Days

Bits of Baseball Lore - X

Special Song | Hold the Baby! | It Took 90 Years to Duplicate It | Boy's First World Series Game | No Sleep? No Problem | It Was Magic! | Rapid Robert and Babe | Gehrig's Disease Infects Yankees? | Stan's Still the Man | Billy Herman, Joe Tepsic, & '46 Dodgers

Be Careful What You Write | Be Careful What You Say in Wateca | Baseball Chicanery - I | Chicanery - II | Hidden Ball Tricks I & II

World War II's Impact on the Game