CONTENTS

Gates Gets Caught

An Unusual Doubleheader

Terry's Side of the Story

Lineup Shenanigans

Baseball's Anthem

Braves' Dissension

Ruth Starts Fast

Babe's First Season

How Catfish Got His Name

Wanted: Catcher

Strange Contracts

A K Almost Becomes an HR

Baseball Lore –

I

Baseball Lore – II

Baseball

Lore – III

Baseball

Lore – V

Baseball

Lore – VI

Baseball

Lore – VII

Baseball

Lore – VIII

Baseball

Lore – IX

Baseball

Lore – X

Baseball

Magazine

Top of Page

|

Bits

of Baseball Lore – IV

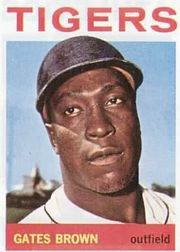

Gates

Brown spent his entire 13-year career (1963-1975)

with the Detroit Tigers as a part-time outfielder

and pinch-hitter. He earned his nickname from the years he spent

in an Ohio prison. In fact, he was serving time when the Tigers

signed him.

One

day in August of the Tigers' pennant-winning

year of 1968, Brown was not in the lineup and

became very hungry. Sneaking into the clubhouse, he came back

with two hot dogs loaded with mustard and catsup. Suddenly, manager

Mayo Smith ordered Gates to

pinch-hit. Stuffing the hot dogs down his shirt, he went to the

plate hoping he would not reach base. However, he smacked a double

and had to slide into second. When he stood up, the mustard, catsup,

hot dogs, and buns were all over his uniform. His teammates roared

with laughter. However, Smith was not amused

and fined Gates $100. "What are you doing

eating on the bench in the first place?" Brown

replied, "I was hungry. Besides, where else can you eat a

hot dog and have the best seat in the house?"

Reference:

Baseball Digest, August 2007 |

|

|

Former

MLB pitcher Don Cardwell died January 14, 2008. In a

14-year

career spent entirely in the National League, the righty toiled

for the Phillies, Cubs,

Pirates, and Braves.

He was involved in an unusual and possibly unique doubleheader while pitching

for the "Miracle Mets."

On Friday, September 12, 1969, with New

York trying to preserve its four-game lead over the Cubs,

the Mets won both ends of

a twinbill at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh

by the same score, 1-0. You say, what's so unusual about that? Not much,

but how about the fact that in each game the only run was driven in

by the pitcher! In the opener,

Jerry Koosman drove in 3B Bobby Pfiel

in the fifth inning with a single and threw a complete game three-hitter

to make his record 14-9. Cardwell started the nightcap

and singled home SS Bud Harrelson in the second. Don

pitched eight innings of four-hit ball before giving way to Tug

McGraw, who saved his 12th game. The victory ran Cardwell's

record to 7-9. Bob Moose and Doc Ellis

were the hard-luck losers before 19,303. The combined time of the two

games was 4:21.

Reference:

Letter of Miracle

Met Art

Shamsky to the New York Times, January 27, 2008 |

Terry's Side of the Story

In

his preface to Barry Levenson's book The

Seventh Game, former Yankee P Ralph

Terry remembers the seventh game of the 1960 World Series at

Forbes Field, Pittsburgh.

- Casey

Stengel had him warm up four or five times during the game.

So Terry was already tired when he came in to get

the final out of the eighth inning.

- After

the Yankees tied the game in the top of the ninth,

Terry returned to the mound. Many second-guessed

Casey, wondering why reliever Ryne Duren

didn't replace Terry. Ralph later

gave Ryne a picture of himself, signing it "Where

the hell were you?" Duren still has that picture.

- Terry

remembers the pitch to Bill Mazeroski as "not

high enough to be a ball, but right at the letters, exactly where

Mazeroski liked it. I knew that he was a good high ball hitter, but

I could not get the pitch down where I wanted it." Because he

was tired?

- "I

felt bad after the game, not for me but for Casey."

Stengel, who was also castigated in the press for

not starting Whitey Ford three times in the Series,

was taking off his uniform in his office. The Old Perfessor

asked Terry why he left the pitch up high. Didn't

he know the scouting report on Maz? Ralph

could only reply that he tried to keep it down but didn't succeed.

Terry concludes, "I was the last person to see

Casey wearing the Yankee pinstripes."

Stengel was fired a few days later for being too

old. Gone also was longtime GM George Weiss.

- Terry

was on the mound in the bottom of the ninth two years later against

the San Francisco Giants.

But that's a story for another time.

|

First

game of a twi-night doubleheader, June 29, 1961, between the

Philadelphia Phillies and the San

Francisco Giants at Connie Mack Stadium. Each manager,

Gene Mauch of the Phils

and Al Dark of the visitors, had both a right-hander

and a left-hander warming up before the game. Since the home team manager

must turn in his lineup card first, Mauch listed P Don

Ferrarese as the leadoff man playing CF. The rest of the order:

Tony Taylor 2B, P Jim Owens in RF, Pancho

Herrera 1B, Don Demeter LF, Charles

Smith 3B, P Chris Short at C, Rube Amaro

SS, and Ken Lehman P. When Mauch saw

lefty Billy O'Dell listed as the pitcher on Dark's

card, he immediately replaced three of the pitchers with right-handed

hitting regulars: Bobby DelGreco CF, Bobby Gene

Smith RF, and Jim Coker C. Although they had

to be listed in the box score, none of the three pitchers actually took

the field.

Dark

retaliated by having O'Dell pitch to the minimum one

batter, DelGreco. Right-hander Sam Jones

then replaced the southpaw. The Giants

won 8-7 on a tenth inning HR by Willie Mays.

Reference:

The

Rules and Lore of Baseball, Rich Marazzi |

On

March 15, 2008, the Los Angeles Dodgers

met the San Diego Padres in the first MLB game in China. During the seventh-inning stretch, the

fans stood and swayed back and forth to the tune of "Take Me Out

to the Ball Game." Without knowing it, the fans were celebrating

the song's 100th anniversary. Here are some tidbits about baseball's "anthem."

- It

was published in 1908 by Albert Von Tilzer and Jack

Norworth. Supposedly Norworth wrote the lyrics

on a subway ride to Manhattan during which he passed a sign that read

"Baseball Today – Polo Grounds." He turned the words

over to Tilzer to add the music.

- The

song didn't become a hit until October of that year when two recordings

of the song moved to the top of the pop charts and continued to sell

through the winter holidays.

- By

1910, "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" was sung at all ML parks.

This happened despite competition from other baseball songs such as

"It's Great at a Baseball Game" and "Take Your Girl to

the Ball Game." Even the famous George M. Cohan's

song "Take Your Girl" didn't catch on.

- Von

Tilzer and Norworth's song may have struck

gold because it came out in time for the exciting 1908 pennant races,

arguably the greatest pair in both leagues in any year. "People

couldn't stop talking about baseball, even after the World Series,"

says Tim Wiles, director of research at the National

Baseball Hall of Fame.

- It

was actually at a theatrical revue, rather than a ball game, that the

song was first heard by an audience. In 1909, it was sung in the Ziegfield

Follies by Nora Bayes, Norworth's

wife. Jack and Nora were the top singing

couple in America at the time.

- Today

"Take Me Out to the Ball Game" is the third most performed

song in America after "Happy Birthday to You" and "The

Star-Spangled Banner." It is performed 2,500 times a year at major

league games alone.

- Norworth

did not attend his first major league game until 1940. In 1958, MLB

presented him with a lifetime pass to all MLB parks. He wrote over 2,500

songs including "Shine On, Harvest Moon."

Reference:

Baseball's Record Hit Turns 100 by Allen Barra, Wall Street

Journal

|

In

1948, Billy Southworth led the Boston Braves

to their first National League pennant since 1914. They lost to the more

talented Cleveland Indians

in six games in the World Series. He had led the Cardinals

to three straight World Series in 1942-4, winning two of them.

During

the off-season, Braves players who demanded more money

were told by the front office that Southworth didn't

think they deserved it. As a result, dissension spread on the team and

ruined their 1949 season. They dropped from 91 wins to 55. The final act

of the disgruntled team was to vote Southworth only a

half share of their fourth place World Series money. Commissioner

"Happy" Chandler intervened and granted Billy

a full share.

Billy Southworth    Alvin Dark Alvin Dark

It

was clear that something had to be done. Since management supported Southworth,

they decided to trade the biggest malcontents, starting with 2B Eddie

Stanky, who had made no secret of his disdain for Southworth's

leadership. The Braves found a willing partner in Leo

Durocher of the Giants,

who wanted nothing more than to be reunited with the 32-year-old Stanky,

whom he had managed at Brooklyn from 1944-7. The

Lip was effusive in his praise: "Stanky'll

drive the pitcher daffy. He'll drop his bat on the catcher's corns. He'll

sit on you at second base, sneak a pull at your shirt, step on you, louse

you up some way — anything to beat you." In addition, the Braves

parted with SS Alvin Dark (26). New

York unloaded two players who had been in Leo's

doghouse from Day One, SS Buddy Kerr and OF Willard

Marshall, along with 3B Sid Gordon and P Sam

Webb.

The

Braves bounced back in 1950, raising their victory total

to 83. But that was still good for only fourth place again. When Boston

started 48-51 in 1951, Southworth was replaced by Tommy

Holmes. After falling to seventh in 1952, the Braves

moved to Milwaukee for the 1953 season.

In

the meantime, Durocher's Giants

made their miracle run in 1951 to beat the Dodgers in

the famous three-game playoff. They lost the World Series to the Yankees

in six but swept the Indians

in four straight in 1954. Dark manned SS for both pennant

winners. Stanky is famous for running to 3B and jumping

on Durocher's back after Bobby Thomson's

pennant-winning HR in 1951. In 1952, he became player-manager of the St.

Louis Cardinals. Dark later managed pennant-winners

in both leagues, including a World Series championship with the A's.

However, neither he nor Stanky matched Southworth's

managerial record.

|

George

Herman Ruth's first professional season was 1914. He signed a

$600 contract with the hometown Baltimore Orioles of

the International League, which was one step below the majors. (The term

"AAA" was not used at that time.) Starting in spring training, George (who was not yet called "Babe")

showed the skills that made him the greatest ballplayer ever.

|

- On

March 7, in his first intra squad game in Fayetteville NC, Ruth

hit a ball far into the corn crop behind right field at the Fair

Grounds. The blow, estimated at 435 feet, surpassed the previous

longest drive ever seen at the field – by Olympic champion

Jim Thorpe – by a large margin.

- In

his first spring training against major league competition, Ruth

pitched three effective innings against the Philadelphia

Phillies.

- Next,

Ruth faced the Philadelphia

Athletics, the defending World Champions, in Wilmington

NC. Although not in peak form, as evidenced by the 17 base runners

he gave up, Ruth held the A's

to two runs in a nine-inning victory.

- In

Baltimore on April 5, Ruth won an exhibition

game against the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Ruth swatted a long drive over the head of the

Dodger RF, who

caught the ball on the run. After manager Wilbert Robinson

gave him hell for playing too shallow, the RF moved so far back

the next time Ruth came up that he figured it

was impossible for the rookie to hit it over his head. Yet that

is exactly what Ruth did, driving the ball beyond

him for a triple at Back River Park, which had no RF fence. The

outfielder talked about Ruth's clout for the

rest of his life. His name was Casey Stengel.

|

The

regular season brought more opportunities for the 19-year-old Ruth

to show his stuff. But we'll save that for another Bit of Baseball Lore. (See below.)

Reference:

The

Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs, Bill

Jenkinson

(2007)

|

Our last episode

talked about Babe Ruth's first spring

training as a professional player. Now we follow him as

he begins his first season with the Baltimore

Orioles in 1914. The Orioles

were an independent team of the International League.

Owner Jack Dunn might have looked forward

to an attendance bonanza as fans flocked to see his new

pitching/hitting phenom, who was quickly dubbed Dunn's

"new babe." However, the Terrapins

of the new Federal League, a third "major" league,

played across the street.

Ruth

didn't disappoint, winning 14 games by early July. However,

to remain solvent, Dunn reluctantly sold

Babe's contract to the Boston

Red Sox. The day he arrived in Boston,

July 11, Babe started and won his first

MLB game, 4-3 over the Cleveland

Indians. However, he played sparingly

the next month since the BoSox

had an excellent staff. They had bought him for the future,

not the present. So they sent him back to the International

League to the Providence

Grays, who were unofficially Boston's

top affiliate. In his Providence debut August 22, Ruth

pitched a complete game victory over Rochester

while poleing two three-baggers. The second one, in the

ninth, landed beside the flagpole on a hill in CF. Amazed

at witnessing the longest drive they had ever seen, many

in the record crowd of 12,000 tossed their straw hats

onto the field.

The

Grays were

locked in a battle with Rochester

and Buffalo

for the pennant. On September 5 in Toronto, the 19-year-old

tossed a one-hit shutout and hit his first professional

HR, which traveled far over the RF fence. Two days later,

he won another complete game and in another two days,

another. With an extra day of rest (three instead of two),

he started and finished yet another victory. Two days

after that, the Grays

visited Newark for a DH. Ruth pitched

the entire first game but lost 2-0. In the nightcap, he

relieved in the seventh but lost again. This dropped the

Grays one-half

game behind Buffalo.

Not

the least bit fatigued, Babe won three

games over the next six days to lead Providence

to the pennant. He averaged over a strikeout an inning

in those contests. He then returned to Boston and pitched

two more games, including a complete game victory over

the New York Yankees

as the Red Sox

finished second behind the Philadelphia

Athletics.

For

the 1914 season, Ruth won

a total of 31 games in the International and American

Leagues. And this despite the fact that he hardly pitched

during his month with Boston

in July and August! As a hitter, he hit what was proclaimed

the longest HR ever seen in three different cities.

|

"Catfish" Hunter

"Catfish" Hunter

Charles Finley

Charles Finley |

Jimmy Hunter grew up in rural North Carolina. In 1964, his pitching prowess, which included several no-hitters, attracted the attention of Kansas City Athletics' scout Clyde Kluttz as well as other scouts. Several teams had offered Hunter a $50,000 signing bonus, but he demanded more. Kluttz thought the kid was worth whatever it took to sign him and pleaded with his boss, A's owner Charles Finley, to go and see for himself.

By plane and limousine, Finley traveled to Hertford NC (population 2,000) to watch Jimmy pitch in a high school tournament. "I saw his curve and couldn't believe it," Finley later remarked. "It was better than any pitcher on my own club had." Charlie visited the family farm, where Jimmy removed his boot to show a right foot missing the little toe and filled with 30 pellets from an accidental shotgun blast from his brother the previous winter. Despite the affliction, Finley signed Hunter for a $75,000 bonus. In return, Charlie received two hams from the family.

With his keen eye for marketing, Finley had one more request. "I told [Jimmy] we had to have a good nickname for him. Looking around this country setting, I came upon 'Catfish.' I told him that we would tell the press he had been missing one night and that his folks found him down by the stream with one catfish lying beside him and another on his pole. He looked at me and smiled and said in that drawl of his, 'Whatever you say, Mr. Finley, it's OK with me.'"

Jimmy "Catfish" Hunter went on to a Hall of Fame career, anchoring the Oakland A's pitching staff during their run of three straight World Series triumphs and then doing the same for the Yankees after an arbitrator ruled him a free agent in December 1974 because of Finley's breach of contract.

|

Charles "Red" Dooin is an interesting character from the early days of baseball who is not well known. He was a journeyman catcher for the Philadelphia Phillies from 1902-1914. The last five of those seasons he was also manager. Here are some stories about him.

- In the off-season, Charlie sang with Dumont's Minstrels in Philadelphia.

- Red didn't like spitball pitchers, whom he accused of "using the ball as a cuspidor." In one game, he put disinfectant on the ball. Umpire Thomas Lynch warned that a repetition would cost Dooin $50. However, some praised Charlie for "contributing to health and decency."

- As manager, Dooin often quarreled with Phillies president Horace Fogel over trades and discipline. Each accused the other of "swell-headedness" and drunkenness. Charlie won the battle when Fogel was banished from the National League in 1912. (More on that in the future.)

- Red's most famous (infamous?) caper occurred in April 1912 during the Phillies' annual pre-season series with the Athletics. He placed the following ad in the Philadelphia Press.

WANTED–A CATCHER, manager Dooin would like one or two husky backstops report at the Phillies' clubhouse to assist in warming up the large squad of pitchers. Dooin says it is a good chance for some youth to "show the goods'"

Dooin was impressed enough with one respondent, Ed Irvin, that he wanted to sign him and then send him to the minors. Irvin, however, was not interested in playing in the minors.

|

|

Reference: Baseball: The Golden Age, by Harold Seymour |

Interesting tidbits involving unusual player contracts – or lack thereof.

- Players tanking after signing lucrative contracts is nothing new. When the National League begin in 1876, Joe Borden was the winning pitcher in the first game for the Boston Red Caps. He had also pitched a no-hitter the previous season for Philadelphia. This led Borden to call himself "Josephus the Phenomenal." The Boston owner rewarded Josephus with a three-year contract, which was unheard of at the time, for a phenomenal $2,000 per season. However, Borden failed to live up to expectations. As a result, he was made the groundskeeper to help earn his salary. Dissatisfied with paying $2,000 a season to a groundskeeper, the Boston directors paid him a lump sum to go away. His career was over at age 22.

- On the final day of the 1892 season, 22-year-old Bumpus Jones walked into the Cincinnati Reds clubhouse and told Manager Charles Comiskey (yes, the namesake of Comiskey Park) he wanted to pitch in the big leagues. Comiskey decided to give him a chance that very day against the Pittsburgh Pirates. So what did Bumpus do? He pitched a no-hitter – the only player to do so without having signed a contract! He is also the only pitcher to toss a hitless game in his first major league appearance. (Bobo Holloman twirled a no-hitter in his first MLB start in 1953 but had previously appeared in relief.) Unfortunately, Bumpus didn't do much more after he did sign a contract for the next season. He won only one game in 1893 for the Reds and New York Giants. He then finished his career in the minor leagues.

- The 1899 Cleveland Spiders were one of the worst teams in baseball history, winning only 20 games while losing 134. They finished a record 84 games out of first. Home attendance was so bad that the Spiders played their last 35 games on the road. On the final day of the season in Cincinnati, the Spiders started a local amateur pitcher and tobacco shop clerk named Eddie Kolb. His pay? A box of cigars. As usual, Cleveland lost, 19-3.

- Jumping to more recent times, the Houston Astros employed a relief pitcher named Charlie Kerfeld who wore #37 in 1985-6. Before the 1987 season, learning that fellow hurler Jim Deshaies would make $100,000, Charlie insisted that he be paid $110,037.37 plus 37 boxes of Jell-O. Constantly fighting a losing battle with his weight, Charlie won only 18 games and last pitched in the majors in 1990.

|

|

|

|

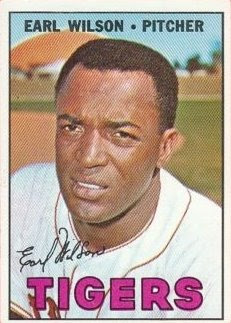

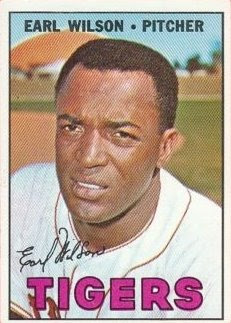

April 25, 1970: Detroit's Earl Wilson almost circled the bases after fanning against the Twins in Minnesota.

- With no one on base, Wilson struck out to seemingly end the seventh inning.

- Tiger 3B coach Grover Resinger noticed that C Paul Ratliff had trapped the ball in the dirt. However, instead of tagging Wilson as required by the rules, Ratliff rolled the back back to the mound.

- At Resinger's urging, Wilson ran to first. Since most of the Twins had reached the dugout, Wilson continued around the bases and began heading home.

- OF Brant Alyea finally retrieved the ball and threw to SS Leo Cardenas covering the plate alongside Ratliff.

- When Wilson tried to return to third, he was tagged out by Alyea who took Cardenas' return throw.

So score that a strikeout for the pitcher with the batter out 7-6-7.

Reference: The

Rules and Lore of Baseball, Rich Marazzi

|  |

|

Alvin Dark

Alvin Dark