CONTENTS

You're Blaming the Wrong Man

Spitter Sign

"Kill the Ump!" – I

"Kill the Ump!" – II

"Kill the Ump!" – III

Costly Clouts

Unusual Plays

Rookie Outcast

Red Was Too Honest

Don't forget your sunglasses!

Baseball Lore –

I

Baseball Lore – II

Baseball

Lore – III

Baseball

Lore – IV

Baseball

Lore – V

Baseball

Lore – VI

Baseball

Lore – VII

Baseball

Lore – IX

Baseball

Lore – X

Baseball

Magazine

Golden Rankings Home

Top of Page

|

Bits of Baseball Lore - VIII

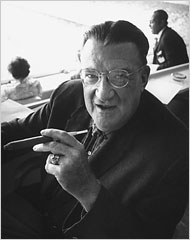

You're Blaming the Wrong Man

"The Wrong Man" is the title of a book excerpt in the 3/9/2009 issue of Sports Illustrated. The subheading says:

From the moment their beloved Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, Brooklyn's jilted fans never forgave the team's owner, Walter O'Malley. Problem is: O'Malley didn't want to go. The culprit was someone else.

O'Malley had wanted a new stadium from the time he became a part owner of the Dodgers in 1944.

- Ebbets Field seated only 32,000 and was not in the best shape.

- To match the perennial excellence of the crosstown Yankees, O'Malley would need more revenue. That quest required, in turn, a larger stadium.

- When Walter assumed full control of the team in 1950, he made a new ballpark in Brooklyn his main goal. He wanted a 50,000-seat stadium that would rival Yankee Stadium.

- However, he would need the cooperation of the city and state to accomplish his aim.

O'Malley seemingly knew how to navigate the political slalom to bring his dream to fruition.

- His father had been a member of the Tammany Hall Democratic machine and had held city office.

- Walter served as a public works contractor and the Dodgers team lawyer.

- However, he more than met his match in Robert Moses, "the most powerful unelected official ever to serve in a U.S. city."

Moses had been a power in New York government for many years, once holding twelve state and municipal positions simultaneously.

- After WWII, he wielded more power than the mayor.

- As the de facto city planner, Moses created his grand plan for the improvement of NYC. His conception called for a new ballpark in Queens near the site that would host the World's Fair in the mid-60s.

As early as 1954, Moses quietly ordered his aides to put roadblocks in O'Malley's way while Robert publicly appeared sympathetic to O'Malley's plan.

- Walter pressed his case with politicians, business leaders, and the press, unaware that what Moses wanted built got built and what he didn't want built didn't.

- The city created the Brooklyn Sports Center Authority to study the feasibility of a new stadium for the Dodgers. Moses pretended to like the idea, causing O'Malley to sell Ebbets Field to a developer.

- However, O'Malley was repeatedly stalled and frustrated by the bureaucracy that, unknown to him, was in Moses' back pocket. For example, months after the Brooklyn commission had been created, Mayor Robert Wagner had yet to appoint anyone to it.

- Potential candidates knew what was going on and refused to take part in the sham.

In the meantime, Los Angeles actively sought a ML team.

- Officials met with O'Malley when the Dodgers stopped in LA on their way to Japan for post-season games in 1956.

- The Californians left the meeting with the impression that O'Malley, who had lived his entire life on the East Coast, was not enthusiastic about moving west.

Home from Japan, O'Malley tried to get his proposal moving again.

- He offered to raise between $4 million and $5 million to invest in sports center authority bonds and to find other investors to buy the remaining $25 million. He also agreed to pay $500,000 per season to rent the new facility.

- However, the sports commission's own engineering consultant was Moses' ally. So he kept asking O'Malley to pay even more to finance additional bonds to cover the anticipated cost.

- Finally realizing that his stadium plan was "dying a slow death" (to use Walter's own phrase), O'Malley reopened the channels to LA. The City of Angels agents sweetened the pot, telling O'Malley "Los Angeles will give you damn near anything."

The LA committee employed a double-barreled approach, persuading San Francisco officials to court Horace Stoneham, the owner of the New York Giants, who was also dissatisfied with the attendance at his ancient ballpark, the Polo Grounds.

- The negotiations between the two clubs and CA officials moved much faster than newspaper accounts indicated.

- At the conclusion of spring training in 1957, O'Malley met with Stoneham, who was thinking of moving his team to Minneapolis, to persuade him to move further west to SF.

Finally realizing the severity of the West Coast threat, Wagner called everyone to another meeting.

- By then, however, O'Malley had figured out Moses' game and declined.

- This gave Moses the opening he needed to cast all the blame on Walter should the Dodgers move.

- Sports Illustrated, wittingly or unwittingly, cooperated in his scheme by allowing Moses to write a long essay in the magazine in which he falsely accused O'Malley of demanding more from the city than he actually had.

Stoneham went public first, announcing the Giants move to SF. It was an open secret that the Dodgers planned to move also.

- A young businessman named Nelson Rockefeller, later NY governor and vice-president of the US, offered to contribute several million dollars toward a new stadium in Brooklyn, but Moses squelched the initiative.

- In early October, the LA city council approved the use of Chavez Ravine for a new stadium for the Dodgers. Soon afterward, the Dodgers issued a one-page press release announcing their move to LA.

The New York Times wished the Dodgers well on the West Coast.

- However, veteran sports writers such as Roger Kahn, Dick Young, and the Times' own Arthur Daley excoriated O'Malley, picturing him as the personification of evil, a man whose greed had caused him to break the hearts of Brooklynites.

- Even Red Barber, the Dodgers beloved announcer, called O'Malley "about the most devious man I ever met."

- O'Malley's fate in history was sealed when Kahn published his best-selling book The Boys of Summer in 1972. In addition to rhapsodizing about the great Brooklyn teams of the 1950s, Kahn portrayed O'Malley as a "cheerless, money-obsessed old man."

- Believing that a real man didn't defend himself, O'Malley never told his side of the story.

When the Veterans Committee elected O'Malley to the Hall of Fame posthumously in 2007, the New York Daily News said: "Say it ain't so."

- It repeated the characterization of O'Malley as a "blackhearted" man who "chose money over memories when he moved The Bums to L.A. after he couldn't squeeze the deal he wanted out of the city to replace creaky Ebbets Field with a new stadium."

Of course, the Dodgers flourished in California from the very first season.

- When O'Malley's papers were made available to a writer several years ago, a note was found from Walter to an old friend. "Bob [Moses] became an enemy when he sabotaged our plans to build a stadium in Brooklyn. He became a benefactor when his opposition became so violent that we left Brooklyn and happily became established in California."

P.S. If Dodger fans want to be mad at O'Malley for something, it should be for running off their beloved announcer, Red Barber. But that's a story for another day.

Reference: Forever Blue, Michael D'Antonio, 2009 |

Walter O'Malley

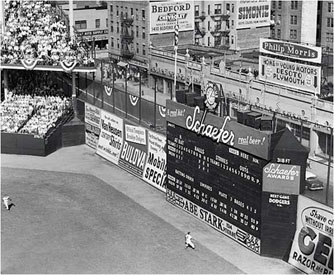

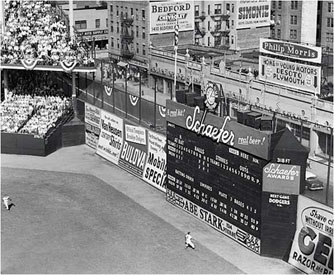

Ebbets Field

Robert Moses

Horace Stoneham and Walter O'Malley

|

Preacher Roe |

Elwin Charles "Preacher" Roe pitched in the NL from 1944 through 1954. After four seasons with the Pittsburgh Pirates, he won 80 games for the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1948-1953. In 1951, he posted a sensational 22-3 record.

In 1955, the year after Preacher's retirement, Dick Young wrote an article in the new magazine Sports Illustrated entitled "The Outlawed Spitball Was My Money Pitch." Roe told Young that "I threw spitballs the whole time I was with the Dodgers." He also claimed, "I wasn't the only one who did it."

One night in June 1960, while taking batting practice in Milwaukee, Cardinals legend Stan Musial was asked by Braves 1B George Crowe, "Did you know that Preacher Roe was using a spit ball when he pitched against you." "Sure," said Stan enthusiastically.

We had a regular signal for it. One day Preacher goes into his motion and Terry Moore, who's coaching at third, picks off the spitter and gives me the signal. Preacher knows I've got it, so he doesn't want to throw the spitter. But he's halfway through his wind-up and all he can change to is a lollipop [nothing ball]. I hit it into the left-field seats, and I laughed all the way around the bases.

|

Stan Musial |

Reference: "Benching of a Legend," Roger Kahn, Sports Illustrated, September 12, 1960

Charley Moran

Irish Meusel

Bill Rariden

|

Umpiring in the 19th century and early 20th century was a risky profession. This was especially true in the National League since Ban Johnson, founder of the American League, insisted that this umpires be respected by players and managers.

The point can be illustrated by two incidents from the 1918 NL season involving rookie umpire Charley Moran. Here is the first incident. The quotations are from The New York Times in the flowery language of the day.

May 5, 1918: Philadelphia Phillies vs. New York Giants @ Polo Grounds

"Charley Moran, who is just in the sprouting state of umpring in the National league, was the guest of honor at a mobbing party yesterday." The incident started when Moran called Phils CF Irish Meusel out at the plate to end the game with the Giants leading 3-2.

- Meusel was at second when SS Eddie Burns shot a bouncer to deep short and beat Artie Fletcher's toss at first. Meusel rounded third and headed for the plate. 1B Walter Holke whipped the ball to C Bill Rariden "and Mr. Meusel and Mr. Ball seemed to arrive simultaneously. Bill Rariden spread-eagled the plate as Meusel came sliding in, and some 10,000 spectators were yelling like Old Ned in the excitement."

- "Umpire Moran seemed to be somewhat undecided about whether Meusel was safe or not. In fact, he waited so long that the Phils took it for granted that the runner was safe. ... When the Phils were dancing around joyously, believing they had tied the score," Moran called the runner out.

- A number of Phillies rushed the umpire and jostled him so roughly "that the umpire squared off, put up his fists, and started to hit straight from the shoulder."

- "In the amazingly short space of one and a half seconds a mob of about 1,000 players and fans had massed around the umpire and Moran had all the appearance of martyr. ... it was difficult to ascertain with the naked eye just what was happening. ... Some say Stock [Phil 3B Milt Stock] tried to plant a well-chosen blow on Moran, while others say that it wasn't Stock, but Burns ... As there were a few thousand inquisitive folks trying to get seats in the front row of the scrap, there are naturally that many versions of the conflagration."

- The two managers, Pat Moran of Philadelphia and John McGraw of New York, pushed there way in and stood in front of Moran to defend him, shoving players away. Their action finally turned the players to the dugout.

- "As the cause of the trouble [Moran] was making his way back under the grand stand to the umpires' dressing room, one man was so angry that he hurled a perfectly good cane at the ump, and didn't get it back, either."

Apparently a large number of Phillie fans attended the game on a Wednesday. Why would the Giants fans rush the umpire since his call clinched the game for their team (unless they had bets on the Phils)? The reporter's estimate of "about 1,000 players and fans" is undoubtedly exaggerated.

The second incident next time ...

|

The second nasty 1918 incident involving rookie NL umpire Charley Moran took place at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. The Phillies were again the visitors, but this time Moran's call angered the home team and its fans. Quotations are again from The New York Times.

Ebbets Field on its Opening Day, 1913

August 10, 1918: Philadelphia Phillies @ Brooklyn Robins, second game of doubleheader

In the fourth inning, with Milt Stock on first, Phils CF Cy Williams smacked a drive down the RF line that Moran ruled fair. That decision eventually developed "into one of the most disgraceful scenes ever perpetrated on a baseball field."

- "About 8,000 witnessed the blow [by Williams]. To 7,000 of those present, the ball hit a part of the fence in foul territory by about four feet. This part of the fence is divided from fair territory by a wonderfully visible whitewash line. Umpire Moran, however, proclaimed himself a majority of one and ruled that the hit was fair."

- "All the Brooklyn players rushed at Moran and tried to convince him that the ball struck foul on the fence. The umpire was unmovable ... The wrath of the players was mild compared to that of the spectators, who howled lustily for the unfortunate arbiter's scalp. They restrained their feelings until after the game, when everything seemed set for a wild demonstration."

The Phils scored three in the fourth after Moran's call and held on to win 3-2.

- "With the last out, ... policemen came from several directions and gathered about Umpire Moran. The arbiter was surrounded by hundreds of angry fans in the wink of an eye, but by some agile work the cops managed to get closest to Moran."

- "In a jiffy there was a series of rushes, but in all of these attacks the police managed to protect the umpire. Finally, when it became evident that there was no chance to reach Moran, the crowd showered the policemen and Moran with handsful of dirt."

- "Moran made his way, with the aid of the police, to the Robins dugout, where he disappeared."

Besides his umpiring career, which included four World Series assignments (1927, 1929, 1933, 1938), Moran had other sports involvements.

- Football

- After playing at Tennessee in 1897, he became player-coach at Bethel College 1899-1901.

- He assisted Pop Warner at Carlisle Indian College.

- Moran served as head coach at Texas A&M from 1909-1914, compiling a 38-8-4 record. He was posthumously enshrined in the Aggie Hall of Fame in 1968.

- 1917-23: He coached Centre College. Led by QB Bo McMillien, the Praying Colonels went undefeated in 1919 and 1921. In the latter season, Centre upset mighty Harvard 6-0. His record at Centre was 42-6-1.

- He compiled a 20-9-2 in three seasons at Bucknell.

- He coached the Frankford Yellow Jackets of the NFL in 1927.

- Charley's college winning percentage was .766, which is 20th best in NCAA history.

- Baseball

- Moran pitched, caught, and played infield for 11 pro seasons.

- In 1903, he appeared in four games for the St. Louis Cardinals as P and SS.

- Charley played 16 games behind the plate for St. Louis in 1908.

|

Charley Moran

Cy Williams

|

Cy Rigler

John McGraw

Dutch Ruether

Zack Wheat |

This is the third installment on the perils of umpiring in the early 20th century. The first two pieces involved umpire Charley Moran. The two incidents described here pertain to one of his colleagues, Cy Rigler. The New York Times is once again our source.

September 17, 1917: New York Giants @ Pittsburgh Pirates, second game of doubleheader

All had gone smoothly in the two games until the seventh inning of the nightcap.

- Giants Manager McGraw "was sent from the field by Umpire Rigler for making undue noise on the bench while the Pirates were at bat. A little later the spectators were surprised to see the entire squad of Giants leaving the field, headed by Christy Mathewson. With a vigorous sweep of his arm, Rigler compelled every one of the visitng players to march away, leaving not a Giant on the grounds except those in the game."

- "Luckily Jacobson and Schauer were out warming up when Rigler issued his exodus order, and both were made use of later. ... Counting McGraw, there were altogether nineteen players who were sent from the grounds."

The Pirates swept the DH from the last place Giants, 9-6 and 5-0.

The second incident involving Umpire Cy Rigler was much more serious and brought the wrath of the home crowd down on him.

May 22, 1921: Chicago Cubs vs. Brooklyn Dodgers @ Ebbets Field

"Pop Bottles Rain as Dodgers Lose"

That was the headline in the Times for the article on the Cubs 6-4 victory before 10,000 fans. "The most shameful demonstration of rowdyism witnessed at the Flatbush ball yard this season" came at the end of the seventh inning and continued into the eighth.

- RF Turner Barber made "a wonderful catch" on P Dutch Ruether's liner closed the seventh leaving two Dodger runners stranded and the Cubs still leading 2-1. However, in making the catch, Barber, "running like the wind ... dug his nose into the ground as he described a somersault after grabbing the ball."

- The crowd thought that Barber dropped the ball, but Umpire Rigler, working the bases, ruled it a catch.

- "Immediately bedlam broke loose. As one man, the Brooklyn team rushed on to the field to protest and to illustrate to Rigler just how the catch was impossible. Disgruntled fans in the stand back of first base shied a few bottles at the umpire. Though several came near hitting the mark, the 'Flatbush confetti' fell harmlessly on the turf."

- As the Dodgers finally took the field, fans in the LF bleachers began throwing pop bottles also, causing LF Zach Wheat to seek shelter in the unoccupied "circus bleachers." The demonstration continued for ten minues until the ammunition supply was exhausted. "A staff of special policemen and vendors made short work of removing the debris and broken glass." But even after the game resumed, several more bottles were tossed at Rigler as he worked behind 1B.

- At the end of the game, two policemen trailed the ump as he exited the field to assure his safety.

Rigler umpired in the NL from 1906 to 1935. He worked ten World Series.

|

In May 2009, Albert Pujols of the Cardinals hit a HR off the McDonald's sign in LF at Busch Stadium, busting the I in BIG MAC. The next day, with the sign not repaired yet, the club put up a sign: OUCH! MY I.

L: Damaged Big Mac Sign at Busch Stadium; R: Bulova Clock at Ebbets Field above scoreboard |

Here are some other HRs that caused damage.

Reference: "Dinger Damage," Sports Illustrated, 6/1/2009

|

Bama Rowell |

|

|

Two different kinds of pickoff plays.

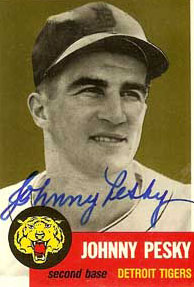

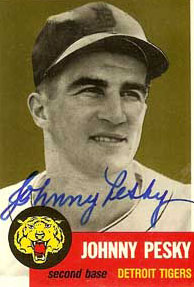

- September 13, 1949, Fenway Park, Boston: Red Sox 2B Johnny Pesky was caught off second when the Detroit C threw to CF Hoot Evers who had snuck in behind Pesky. Johnny ran to third but Evers' throw beat him for a 2-8-5 pickoff.

- July 28, 1975, Three Rivers Stadium, Pittsburgh: Pirates SS Frank Taveras led off the bottom of the fifth against the Philadelphia Phillies with a single. Then, with P Bruce Kison attempting to bunt, 1B Dick Allen charged the plate, and 2B Dave Cash was tardy moving to first. However, RF Jay Johnstone ran toward 1B. When Kison didn't bunt the ball, C Johnny Oates threw to Johnstone, who put the tag on Taveras. So the pickoff was scored 2-9.

|

|

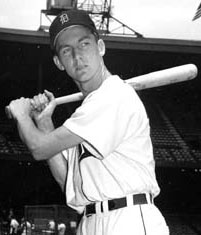

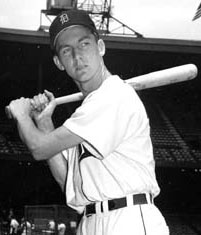

In 1953, the Detroit Tigers signed 18-year-old OF Al Kaline with a $35,000. The rules at that time required a player who signed for more than $6,000 to spend two seasons in the majors. This was done to discourage large signing bonuses.

The Bonus Baby didn't get a warm reception from his Tiger teammates. Let Al tell the story himself.

I wasn't accepted right away, rightfully so because when I joined the ballclub, that meant somebody had to be let go.

I was an outcast. I couldn't go have a drink with the guys, and they wouldn't invite me to dinner. The two guys who helped did so because it was their jobs. Ted Gray was our player rep, and he helped me by telling me the basics such as how much to tip the clubhouse guys.

I was mostly a defensive player and baserunner my first year and didn't play much. Our manager, Freddy Hutchinson, told me to sit beside Johnny Pesky every game to learn the ins and outs of the game. Johnny helped me a lot.

I started to be a pretty good player pretty quick, and the other players took a liking to me also because I was at the park all the time. I lived in downtown Detroit and would get there early to throw batting practice and shag for the veterans. I knew my place.

By his second full year, at age 20, Kaline became the youngest player to win a batting title.

- Al hit .340 with 27 HR and 102 RBI. He also led the AL in hits (200) and total bases (321).

- He finished second in the 1955 MVP voting to Yogi Berra.

- A fixture in RF at Tiger Stadium, he never won the batting crown again in the 22 seasons of his HOF career – all with Detroit. He ended with 399 HR and a .297 lifetime average.

- At age 33, Kaline finally played on a pennant winner, the 1968 Tigers World Champions. After hitting .287 in 102 games during the season, he went 11-29 (.379) in the Series with 8 RBI and 2 HR.

Reference: "I Remember ... Al Kaline," Sporting News, 5/11/2009

|

Young Al Kaline

|

After losing to the Cardinals in seven games in the 1964 World Series, the Yankees had fallen on hard times just two years later.

- New York was in tenth (last) place in the AL standings, 28 games behind first place Baltimore.

- A mere 413 fans showed up in 65,000-seat Yankee Stadium for the game against the Chicago White Sox on Thursday afternoon, September 22, 1966.

- There were some mitigating circumstances that helped limit the attendance. Three straight games had been postponed because of incessant rain. The Thursday game was not on the original schedule but was a make up of one of the rained-out games. And the rain continued during the makeup game. Some contended the contest should also have been cancelled because of the weather.

- The White Sox won 4-1, dropping the Yankees' record to 66-87.

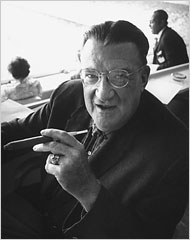

Red Barber

The game led to the firing of announcer Red Barber, who had moved to the Yankees from Brooklyn after the 1953 season.

- During the game, Barber asked the TV cameras to pan the empty stands.

- The Yankees' head of media relations vetoed Red's request.

- Undaunted, Barber said, "I don't know what the paid attendance is today, but whatever it is, it is the smallest crowd in the history of Yankee Stadium, and this crowd is the story, not the game."

- On September 21, the day before the fateful game, Yankees' president Mike Burke, recently appointed by the new team owner, CBS, had stated that he had no plans to change the broadcasting crew, which consisted of Barber, Phil Rizzuto, Jerry Coleman, and Joe Garagiola.

- A week later, Burke invited Barber to breakfast at the Plaza Hotel, where Burke relieved Red of his broadcasting duties.

- The 58-year-old Barber, a Hall of Fame announcer who started in the major leagues in 1934, never got another announcing job in baseball.

Returning to the Yankees' attendance, only 1,440 showed up the next afternoon, September 23, to watch the first game of the Red Sox series. The Saturday game drew 5,897 before the final home game of the season on Sunday attracted a respectable crowd of 16,467.

|

Don't forget your sun glasses!

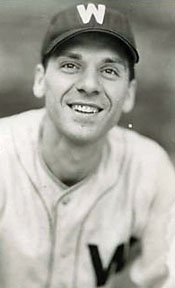

Dutch Leonard

George Binks

Hal Newhouser

Hank Greenberg

|

It was Sunday, September 23, 1945.

- The Washington Senators played a doubleheader at Philadelphia to end their season.

- The rest of ML baseball would play for another week, but Senators' owner Clark Griffith, always looking for ways to increase revenue, had rented the stadium named after him to the Washington Redskins for the last week in September.

- He had played the home games scheduled for the last week of the season as part of doubleheaders during teams' earlier visits to Washington. Of course, the doubleheaders put a strain on the Senators' pitching staff and meant fewer starts by their best pitchers.

- Having taken three of five from the Tigers in the Nation's Capital in their prevous series, the Senators entered the twinbill in second place, 1.5 games behind Detroit. They had as many wins as the Tigers, 86, but three more losses, 66 to 63.

The first game of the doubleheader against the Athletics went into extra innings.

- Connie Mack's team counterbalanced the Nats' 3-run 5th by scoring 3 in the 8th off Dutch Leonard, one of four knuckleballers in Washington's starting rotation.

- Entering the 12th, the sun, which had been hiding in a murky sky all day, came out while Washington was at bat. CF Sam Chapman stopped the game and called for his sun glasses.

- After the Senators failed to score, George "Bingo" Binks didn't bring his dark glasses as he headed out to CF. With two outs and none on, A's LF Ernie Kish lofted a high fly that should have retired the side. But Binks lost the ball in the sun, and it fell for a double. After Dick Siebert was purposely passed, George Kell stroked a single that sent Kish over the plate with the winning run.

- The Nats bounced back to take the nightcap by the same score, 4-3, with a run in the top of the 8th. The game was called by darkness at the end of that inning. Shibe Park's lights could not be turned on because of a league rule that prohibited finishing a game started in daytime by turning on the lights.

- Meanwhile, the Tigers lost at home to the Browns, 5-0. So Washington gained a half game to put them one behind. If the Nats had won the first game, they would have been tied with Detroit.

Born George Binkowski in Chicago in 1914, Binks ran away from home at age 18 by hopping a freight train headed southwest. At dawn in Bloomington IL, George and a friend hopping from the moving train to join several hundred kids trying out for a minor league team. #384 in the lineup, Binks slept in the dugout for two cold April nights, stuffing newspapers into his clothes for warmth. He made the final cut and was paid a few dollars, which allowed him to eat for the first time in days.

His minor league career started in class D and eventually reached AA. Classified 4-F because he was deaf in one ear, George made his ML debut with five games for the Senators in 1944 at age 30.

Calling himself "Bingo" because he claimed to hit well in the clutch, Binks played in 145 games for the Nats in '45, hitting a respectable .278 with 81 RBI, tops on the team. Like so many wartime players who lost their starting jobs if not their roster spots when the veterans returned, Binks appeared in only 65 contests in '46 before being traded to the A's. His ML career ended with the Browns in '48.

America's #1 sportswriter, Grantland Rice, characterized the final week of the AL season like this.

In the most baffling and peculiar pennant race on record, Washington's Senators will now spend the remainder of the final week of the baseball season playing gin rummy, pinochle, poker and golf while chewing their nails. They will be wondering whether Detroit's staggering Tigers will back into or out of the pennant country.

With only four games left against Cleveland and St. Louis, Detroit now needs only one victory for a tie and two for the flag.

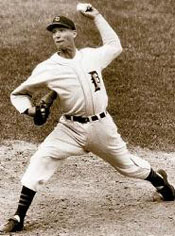

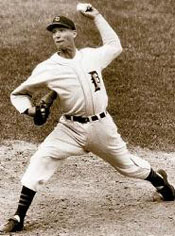

Thanks to a rainout, the Tigers played a doubleheader against the Indians in Detroit on Wednesday, September 26.

- Detroit romped in the opener 11-0 for ace Hal Newhouser's 23rd victory.

- But with a chance to clinch the pennant, the Tigers faltered in the nightcap, losing 3-2. That made their final two games in St. Louis meaningful.

- Persistent rain forced the teams to play a doubleheader on Sunday, September 30.

- The Senators gathered at Griffith Stadium with their bags packed. If the Tigers lost both games, the resulting tie would be settled by a one-game playoff in Detroit. Dutch Leonard had already been sent to the Motor City to rest for a possible start the next day.

- The rain continued to fall, and the games would have been cancelled except for the pennant race. The first game was delayed while straw and newspaper was laid down to soak up the standing water on the field.

- The Browns held a 3-2 lead in the top of the 9th when Tiger slugger Hank Greenberg swatted a three-run HR to clinch the pennant. The second game, rendered meaningless, was cancelled.

If the Senators had won the first game of that fateful doubleheader in Philadelphia the previous Sunday, the Tigers would have had to play and win the second game in St. Louis in order to claim the AL title.

|

|