CONTENTS

Superstitions - I

Interesting Facts about the All-Star Game

Be Careful What You Write

Be Careful What You Say in Wateca

Baseball Chicanery - I

Baseball Chicanery - II

Hidden Ball Tricks - I

Hidden Ball Tricks - II

World War II's Impact on the Game - I

World War II's Impact on the Game - II

Baseball Lore –

I

Baseball Lore – II

Baseball

Lore – III

Baseball

Lore – IV

Baseball

Lore – V

Baseball

Lore – VI

Baseball

Lore – VII

Baseball

Lore – VIII

Baseball

Lore – IX

Baseball

Lore – X

Baseball

Magazine

Golden Rankings Home

Top of Page

|

Bits of Baseball Lore - XI

Superstitions - I

Jason Giambi

Wade Boggs

|

Some weird superstitions past and present.

- Jason Giambi has a strange way of trying to break out of a slump. He puts on a gold thong. "It works every time," he told the New York Daily News in 2008 when he played for the Yankees. "I only put it on when I'm desperate to get out of a big slump."

The habit even spread to his teammates. Derek Jeter said it worked although "it's so uncomfortable running around the bases. I had it over my shorts and stuff. I was 0-for-32 and I hit a homer on the first pitch. That's the only time I've ever worn it." Johnny Damon also admitted donning the golden panties "probably three times."

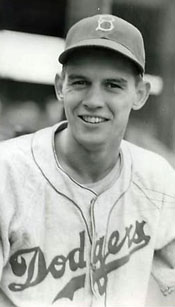

- Wade Boggs ended his 18-year career in 1999 with a .328 average, good enough to earn induction into the Hall of Fame in 2005. Can you blame the 12-time All Star for adhering to the same routine before every game? First, he ate fried chicken, then he took batting practice at precisely 5:17 before each night game. He topped off his preparation by running sprints at 7:17 and drawing the word "Chai" (Hebrew for "life") in the dirt before stepping to the plate.

- When P Matt Garza joined the Chicago Cubs via a trade from the Rays in 2011, he brought his superstition with him. He always eats Popeye's chicken for his pregame meal before each start. As the Cubs began their home season, he found a Popeye's near Wrigley Field. Matt compiled a 10-10 record with a 3.32 ERA that season, then 5-7 (3.91) the next year. The Cubs traded him to the Rangers during the '13 campaign. Maybe he should try MacDonald's or Burger King.

Ryan Dempster, who was Garza's teammate with the Cubs, has a similar habit. He goes to the same Italian restaurant the night before every start at Wrigley Field.

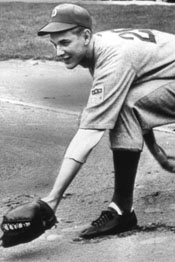

- What is it about the Cubs and whacky pitchers? Garza and Dempster followed in the footsteps of perhaps the most superstitious Cubbie ever: Turk Wendell. The reliever's many eccentricities included:

Always leaping over the baselines when walking to and from the mound;

Chewing black licorice while pitching and brushing his teeth between innings;

After each batter, no matter what happened, picking up the rosin bag and throwing it down;

Wearing a necklace decorated with the sharp teeth of wild animals he killed.

Also, in honor of his favorite number, nine, he asked the New York Mets to make his 2000 contract worth $9,999,999.99 in honor of his uniform number, 99.

To be continued down the road ...

|

Matt Garza

Ryan Dempster

Turk Wendell jumping over foul line leaving mound

|

Interesting Facts about the All-Star Game

- In the first All-Star game in 1933, each league's roster consisted of 18 players. Today [2013] the number is 34 per league.

- The managers for the first game were legends John McGraw for the NL and Connie Mack for the AL. Since then, the managers of the previous year's pennant winners head the teams.

- The method for picking the rosters has gone back and forth through the decades.

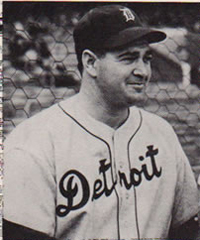

For the first three years, the managers picked the team. In 1935, Detroit skipper Mickey Cochrane snubbed his own 1B, Hank Greenburg, in favor of Jimmie Foxx and Lou Gehrig despite the fact that Hammerin' Hank had 110 RBIs at the break.

In 1936, the fans named 16 players per league, and each manager added five.

Then from 1937-46, the All-Star managers picked the entire team.

From 1947-57, the fans picked the eight starters and the managers completed the rosters.

1958-69: Players, managers, and coaches picked the starting lineups; the All-Star managers completed the rosters.

1970-2002: Fans selected the eight starters; All-Star managers did the rest.

2003: Internet voting started.

- Fan voting has created some strange situations over the years. In 1956, Cincinnati fans flooded the ballot boxes so that five of the eight NL starters were Reds. The following year, Reds fans did even better, picking seven of their heroes to start. But Commissioner Ford Frick stepped in and replaced Wally Post and Gus Bell with Hank Aaron and Willie Mays. He also stripped the fans of their right to vote.

- In 1974, Steve Garvey wasn't listed on the NL ballot because he had split time between 3B and 1B. But a write-in campaign put him in the starting lineup at 1B. He rewarded his fans by winning the MVP trophy for the All-Star Game as well as the MVP award for the entire NL season.

- That same year, the opposite situation occurred in the AL. The fans voted Luis Aparicio as the starting SS even though he had been released by the Red Sox before the season started.

- A similar situation occurred in 1989 when the fans voted Mike Schmidt as the NL's 3B even though he had retired two months before the All-Star Game. Mike didn't play.

- Two players with batting averages under .200 sneaked into the starting lineups, both in the strike-shortened 1981 season when the game was held August 9 after the strike was settled.

- The fans voted for Davey Lopes of the Dodgers for 2B even though he was hitting .169 when the strike started.

- Reggie Jackson of the Yankees won the fan vote for an OF spot despite having a .199 average.

Be Careful What You Write

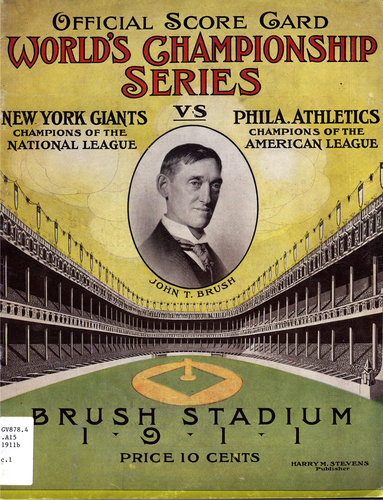

John McGraw and Christy Mathewson before 1911 World Series in the Giants brand new black uniforms

McGraw and Connie Mack at the 1911 World Series

Rube Marquard

Eddie Plank

Frank Baker

Eddie Collins

|

Two New York Giants pitchers sparred in the press during the 1911 World Series.

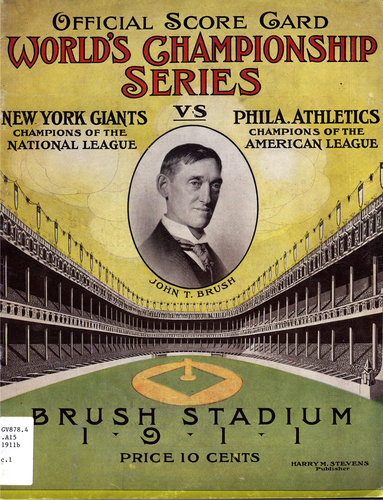

- Giants ace Christy "Big Six" Mathewson prevailed over the defending World Champion Philadelphia Athletics in Game One 2-1 at the Polo Grounds (officially called "Brush Stadium" in honor of the team owner) in New York.

- The series alternated sites since the two cities were so close. So after taking the Sabbath off (since both cities had "Blue Laws" prohibiting public events on Sundays), Rube Marquard took the hill for John McGraw's team. Connie Mack sent Eddie Plank to the hill.

The game was tied 1-1 as the A's came to bat in the bottom of the sixth.

- Philly's third-sacker, Frank Baker, led the AL in HRs that season with 11. So McGraw wanted his pitchers to keep the ball down to him.

- After the first two batters were retired, Eddie Collins doubled to LF. That brought Baker to the plate.

- With the count one-and-one, Marquard fired a high fastball. As the New York Tribune described it,

The sphere came billing and cooing along about shoulder high.

- Baker smacked it out of the park to give the A's a 3-1 lead that Plank preserved.

- After the game, McGraw didn't hide his fury.

A good pitcher isn't supposed to give up a home run in a situation like that.

1911 World Series at Shibe Park, Philadelphia Both Mathewson and Marquard had signed contract to provide daily newspaper commentary during the Series.

- The New York Herald paid Christy $500 for his efforts while Rube did the same for the New York Times, undoubtedly for a lesser amount since Matty was the non-pareil star of baseball. Both columns were actually ghostwritten, Matty's by John Wheeler and Rube's by Frank Menke.

- Marquard was forthright in his column the next day, giving kudos to Baker.

He deserves the credit for the victory, and I will bear the blame, for the fault was mine. I gave him just the kind of ball he had been looking for, though he had bitten on two curves already. ...

Baker is a bad man, and I had been warned against him, and I had the right dope, too, but at the last moment I switched, because I thought I was working it too hard. ... when he came up in the sixth I fully intended to follow instructions and give him curved balls. But after I had one strike on him and he had refused to bite on another outcurve which was a little too wide, I thought to cross him by sending in a fast high straight ball the kind I knew he liked. [Catcher Chief] Meyers had called for a curve, but I could not see it, and signaled a high fast ball.

Either he knew the signal from Collins, who was on second, or he outguessed me, for he was waiting for that fast one, and sent it over the fence ... I will never give Baker that kind of ball again, and I expect to strike him out several times more before the series is over.

- Marquard's phrase "I could not see it" refers to his statement earlier in the article that the pitcher looks into the sun at Shibe Park, which he was not used to.

Rube had taken responsibility, although he offered the possibility of sign-stealing by the A's as an excuse. The Giants should have been able to put the incident behind them and move on.

- But that was not to be because Mathewson's ghostwriter published this in the Herald under a headline that read: Marquard Makes the Wrong Pitch.

Marquard served Baker with the wrong prescription ... That one straight ball ... right in the heart of the plate, came up the 'groove' ... [and] was what cost us the game.

- The article contained information that Wheeler could not have known on his own. The report stated that Rube had specifically gone against McGraw's directions on how to pitch to Baker and also against Matty's advice based on what Baker had done against him in Game One when Matty struck him out with curve balls but gave up a single on a fast one.

I told Marquard about that, but he evidently thought that Baker would not be looking for a fast one at that time, and looked to sneak it over. The Athletics' third baseman outguessed Marquard very cleverly, and made the hit that won the game for his club.

- Matty too suspected that Collins may have tipped the pitch to Baker and threatened the A's that, if anyone did so while he was pitching, he would bean him.

- Marquard fumed. It was one thing for reporters to criticize him but not a teammate and especially not the revered team leader.

- Mack posted Christy's article in the A's clubhouse the next day at the Polo Grounds.

Polo Grounds in 1913 |

Red Ames

|

McGraw sent his ace to the mound for Game Three on only two days rest. Matty had set himself up for extreme scrutiny when he faced Baker.

- Frank grounded out in the second and fourth and flew out in the seventh.

- When the Game Two hero came up in the ninth with one out and no one on, Christy was nursing a 1-0 lead. No Athletic had reached second until the eighth inning. So the Giant righty hadn't low-bridged anyone.

- Matty got two quick strikes and appeared to have struck out Baker when he swung and missed. But the umpire ruled that he had tipped the ball.

- The next delivery was a high hard one that Baker lined into the RF stands to tie the game.

- When the inning ended with no further damage, Marquard asked Matty what he threw Baker.

The same thing you did, Rube. I gave Baker a high fast one. I have been in the business a long time and I have no excuse.

- Marquard couldn't resist telling his ghostwriter about the exchange and having him add this in the next day's column.

Will the great Mathewson tell us exactly what he pitched to Baker? He was present at the same clubhouse meeting at which Mr. McGraw discussed Baker's weakness. Could it be that Matty too, let go a careless pitch when it meant the ballgame?

- Rube added: It was the hardest game to lose I ever saw.

The A's scored two in the 11th off a weary Mathewson to win 3-2 and take a 2-1 lead in the Series.

- After a full week of rain, the Series finally resumed in Philadelphia with Matty back on the slab.

- Already tagged with the sobriquet "Home Run" and greeted like a returning war hero, Baker smacked two doubles, scoring a run and driving in another as the A's prevailed 4-2. When Frank came up in the 7th with a runner on third, Matty walked him intentionally as the crowd gleefully booed.

- In New York the next day, Marquard lasted only three innings, McGraw removing him after a three-run third. But the Giants plated two in the ninth and one in the tenth to stave off elimination 4-3.

- Sensing that Big Six needed more rest, McGraw decided to hold him for the deciding game. But that meant starting Red Ames, who managed only an 11-10 record. The A's had a field day, romping 13-2 to keep the championship flag in Philly.

Reference: The Old Ball Game, Frank Deford (2005)

Top of Page |

Be Careful What You Say in Wateca

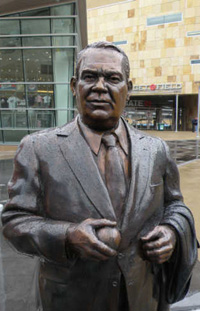

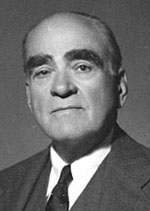

Calvin Griffith was elected president of the Washington Nationals when his uncle, Clark Griffith, died in October 1955.

- Calvin moved the franchise to Minnesota for the 1961 season.

- In 1962, the Minnesota State Commission on Discrimination fielded a complaint against the Twins for being the only ML team still segregating black players during spring training in Florida.

- It took two years of heavy pressure by the state, intense media scrutiny, and picket lines organized by civil rights organizations before Griffith relented.

Still, the Twins were popular and successful in their new home.

- Minnesota reached the World Series in 1965, losing to the Dodgers in seven.

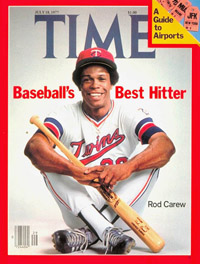

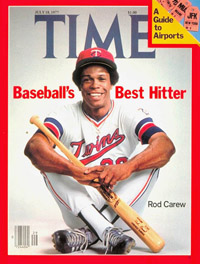

- In 1967, a 21-year-old native of the Canal Zone, Rod Carew, joined the club fresh from Class A. Installed at 2B, Rod hit .292 to contribute to the Twins resurgence that fell a game short of besting the Red Sox for the AL pennant.

- Griffith, who was not averse to looking over the shoulder of his manager, insisted that Sam Mele keep the rookie in the lineup.

Carew continued his Hall of Fame career in the Twin Cities through the 1978 season.

- He led the league in hitting an astounding seven times.

- With free agency a new phenomenon in baseball in 1976 thanks to court rulings, Carew signed a three-year contract with the Twins.

- With fans praying that Griffith would negotiate a new contract with Rod for the 1979 season and beyond, that possibility went up in smoke thanks to impromptu remarks by the team president at a private dinner.

On September 28, 1978, just before the last weekend of a season that would see Minnesota finish 4th in the AL West, 19 games behind the Kansas City Royals, Clark traveled south to the rural town of Waseca to play some golf and speak to the local Lions Club that evening.

- After eating a nice meal and undoubtedly consuming some adult beverages, Griffith began his talk.

- Noticing that everyone in the audience was white, he gave the real reason he moved his franchise from Washington.

I'll tell you why we came to Minnesota. It was when I found out you only had 15,000 blacks here. Black people don't go to ball games, but they'll fill up a rassling ring and put up such a chant it'll scare you to death. It's unbelieveable. We came here because you've got good, hardworking, white people here.

- Unfortunately for Griffith, a staff writer of the Minneapolis Tribune was in the audience. Nick Coleman wasn't working that night but attending as a Lions Club member. Years later, Nick recalled:

I was wincing the whole time thinking, "you don't want to say that."

- Coleman had no tape recorder nor any paper to take notes, but he wrote down everything he remembered as soon as he got home.

Clark was just getting warmed up.

- He spoke disparagingly of Carew's judgment.

Carew was a damn fool to sign that contract. He only gets $170,000 and we all know damn well that he's worth a lot more than that, but that's what his agent asked for, that's what he gets. Last year, I thought I was generous and gave him an extra 100 grand, but this year I'm not making any money so he gets 170 - that's it.

- Clark made additional comments about blacks before he finally sat down.

The next day, Coleman called his editor and asked if he wanted him to write a story about Griffith's speech. After consulting his bosses, the editor gave the go-ahead and ran the article in the Sunday paper. Needless to say, a furor ensued.

- Carew shared his indignation with Jet magazine:

I will never sign another contract with this organization. I don't care how much money or how many options Calvin Griffith offers me. I definitely will not be back next year. I will not come back and play for a bigot. I'm not going to be another nigger on his plantation.

- Rod played the last seven seasons of his career for the California Angels. He never won another batting crown but continued to be productive, hitting over .300 the first five years before ending .295 and .280.

This story has a surprise ending, however.

- Rod was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1991.

- He later recalled the day he was notified of his election.

When I first got the news that I was going into the Hall of Fame, he [Griffith] was the first person I called. It was 3 o'clock in the morning for him in Helena, Montana, and I woke him up. I called him before my mom because I owed him that much respect.

Cal never lived down his intemperate remarks in Wateca. When he died in 1999, most obituaries mentioned that speech as being the low point of his baseball career and even his life.

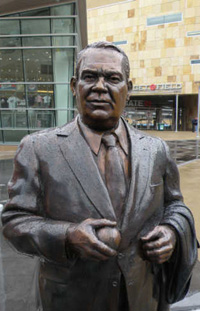

Both men have statues on the grounds of the new Twins ballpark that opened in 2010.

References: " Calvin Griffith: The Ups and Downs of the last Family-Owned Baseball Team", Kevin Hennessy, The National Pastime, 2012

"Angered by Owner's Race Slurs, Carew Vows Not To Play For Twins Again,"

Jet, October 19, 1978

Top of Page |

Calvin Griffith

Rod Carew 1977

Calvin Griffith Statue

Rod Carew Statue

|

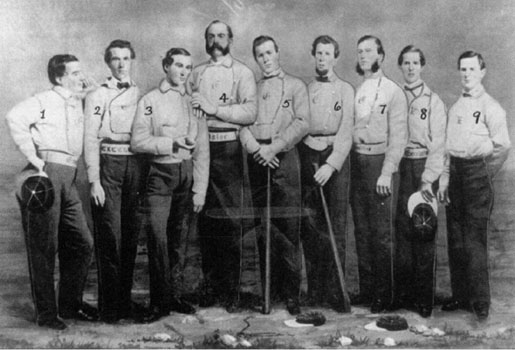

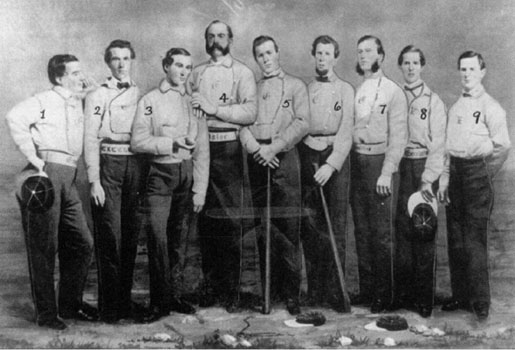

The first use of signals in baseball seems to have been undertaken by the Brooklyn Excelsiors in 1860.

- Reporting on a game in which the Brooklyns walloped the local team, the Rochester Everning Express reporter wrote: The catcher was also proficient in his part and won encomiums for the manner in which he would telegraph advances to be gained, or the direction as to which one of the fielder should take a "fly." The Excelsiors were proclaimed U.S. champions that year when the fledgling sport was still known as "The New York Game."

- Four years later, a Brooklyn Eagle observer wrote: All pitchers should follow example of the Excelsior players in 1860. The pitcher and catcher of the Excelsiors had regular signals whereby the pitcher knew when to throw to the bases.

Brooklyn Excelsiors

Brooklyn Excelsiors

When pitchers were allowed to throw overhand in 1884, they developed an array of deliveries.

- This forced catchers to move up from their previous position 10-12' behind the batter and squat right behind him.

- It also demanded that the battery be on the same page for each pitch lest the catcher be fooled and give up a wild pitch or passed ball.

- So backstops signalling the pitches became standard practice.

Inevitably, some teams tried to divine the signs of their opponent to increase their batters' chances of making solid contact.

- This trend was enhanced by an 1887 rules change that permitted the use of "coachers" next to first and third base.

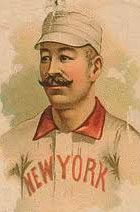

- One of the jobs of either or both of the coachers was steal the catcher's signs to the pitchers. Wrote John Montgomery Ward, one of the leading pitchers of the day, in his 1888 treatise Baseball: How to Become a Player: The coacher, standing at first or third, makes some remark with no apparent reference to the batter, but really previously agreed upon, to notify him what kind of ball is going to be pitched.

- Such sleuthing was partially prevented by backstops using their catchers' mitts to shield their fingers between their legs from the prying eyes of the coachers.

- Still, some teams broke the code. Ward himself was a victim in 1882. Some years ago, the Chicago club gave me the roughest kind of handling in several games, and [King] Kelly told me this winter that they knew every ball I intended to pitch, and he even still remembered the sign and told me what it was. Ward went 19-12 with a 2.59 ERA that season, but against Chicago he surrendered 36 runs in 35 innings, losing three of four. That margin gave Chicago the pennant over Ward's Providence Grays.

- In the 1889 championship, Brooklyn stole the signals of the New York Giants, plating 32 runs in the first 31 innings to lead three games to one. After C Buck Ewing figured out that the enemy were on to his signs, the Giants took five straight to win the best-of-nine series.

Such sign-stealing was considered within the bounds of good sportsmanship because it relied on the carelessness of the catcher or pitcher in tipping pitches. However, it didn't take long for some to employ "ungentlemanly" means to gain an advantage.

To be continued ...

Reference: The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World, Joshua Prager (2006)

|

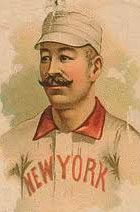

John Montgomery Ward

George "King" Kelly

Buck Ewing

|

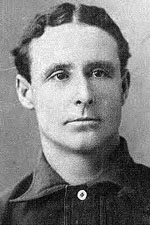

Pearce Nugent Chiles

Arlie Latham

Tommy Corcoran

Tim Hurst

Huey Jennings

Eddie Collins

Ty Cobb

|

It began at the Fair Grounds racetrack in New Orleans in the winter of 1898.

- 31-year-old Pearce Nugent Chiles had bounced around the minor leagues but would finally get his first chance with a major league club, the Philadelphia Phillies, in the spring.

- Pearce did what many racing fans do. He peered at the horses through opera glasses. Spotting a group of boys playing baseball nearby, he aimed his binoculars at the game. He immediately realized he could see and interpret the catcher's signs.

- When he joined the Phillies - perhaps to enhance his chances of making the club? - he shared his discovery with C Morgan Murphy, who liked the idea. So the club purchased for $60 (quite a sum in 1899) a double lens range glass of the finest make ... By using this glass Murphy could see a freckle on the catcher's nose at five furlongs. (Charles Dryden, North American Magazine)

- Armed with the binoculars, Murphy stationed himself in a window on the top floor of a three-story tenement house beyond the CF wall at the Baker Bowl, the Phillies' home park. His partner, Chiles, coached 3B when not playing.

- Murphy used a simple system to communicate the pitch: he held a newspaper horizontally for a fastball and vertically for a curve. Pearce relayed the call to the batter with a coded shout. It could have been as simple as calling the batter's first name for a fast ball ("C'mon, Joey!") and just yelling encouragement with no name for a curve.

- Did the system help? Well, the Phils went 94-58 in '99, good for third place in the National League after finishing 78-71 in sixth place the year before.

By the start of spring training in 1900, rumors of a sign-stealing scheme in Philly circulated through the league. Chiles tried to stay one step ahead of the opposition by developing an even better plan.

- He had a push-button installed in Murphy's lookout perch and a buzzer buried in a box under the 3B coaching box. A wire ran from the button in the apartment building along the LF stands to the clubhouse to the bench to the coaching box.

- Probably because the manager decided that his .216-hitting utility infielder was more valuable to the team as a coach, Pearce appeared in only 33 games (mostly on the road?).

- Murphy pushed the button to make the buzzer vibrate for a fast ball and didn't press it for a curve (or vice-versa).

- The Phils compiled a 36-20 home record that season as opposed to 24-35 on the road.

- But the plan unravelled on September 17 during a game against Cincinnati. The Redlegs' 3B coach Arlie Latham noticed that his counterpart Chiles stood with one foot in the coaching box even though the sunken box was filled with rainwater. Latham told team captain Tommy Corcoran who ran out of the visitors' dugout and began digging with his spikes in the coaching box until his shoe found a small wooden box, which he opened to reveal the buzzer and its attached wire.

- The players and the 4,774 fans turned their attention to umpire Tim Hurst. But he shrugged it off as part of the game, quoting a hero of the recent Spanish-American War. Back to the mines, men! Think on that eventful day in July, when Dewey went into Manila Bay, never giving a tinker's damn for all the mines concealed therein. Come on. Play ball!

- Philadelphia won both ends of the DH that day. However, the loss of their electrical edge caused them to hit only .292 during the remaining ten games of the home stand after smacking the horsehide at a .336 clip the first 13 contests.

- His scheme exposed, Chiles never played another ML game after the 1900 season. He entered a Texas prison in 1901 until escaping a little over a year later.

When word of the deception spread, many reacted much more indignantly than umpire Hurst.

- Ferdinand Abell, co-owner of the Brooklyn team, called for Philadelphia's third-place finish and all the statistics of its batters to be declared invalid.

- Reporter Dryden suggested that the umpire check each bench before each game to make sure every player was present.

- The Sporting News, the nation's premiere baseball publication, editorialized: The explanation that everything is fair in baseball will not suffice. An advantage obtained by underhanded methods is unsportsmanlike.

- Phillies' co-owner John Rogers dismissed the criticism. First of all, he claimed that the buzzer embedded in his field was left over from a traveling circus. Furthermore, what was the big deal about using binoculars to steal signs? If it is fair to use your naked eyes to discover signals, there can be no objection to the use of glasses.

- Even though the league took no action against the Phils, the incident crystallized public opinion behind the notion that stealing signs with anything other than the naked eye was wrong.

- Still, the negative reaction didn't prevent the 1909 New York Highlanders from using a similar scheme to improve from 51-103 in '08 to 74-77. By June, visiting teams had become suspicious. Washington Senators manager Joe Cantillon instructed P Walter Johnson and C Gabby Street to use no signs. The result was a 7-4 victory despite four wild pitches by the "Big Train." Detroit manager Hughie Jennings, also suspecting foul play, sent his trainer to inspect the CF wall. Climbing over the fence into a narrow space in front of an advertising billboard, the trainer saw a man running away with field glasses.

- Again, nothing was done to the Highlanders. However, that December the American League board of directors passed this resolution: RESOLVED. That it is the sense of this Board that any manager or offical found guilty of operating a sign tipping bureau should be barred from baseball for all time. However, no actual rule was passed.

The issue surfaced again as the Philadelphia Athletics and New York Giants prepared for the 1911 World Series.

- Rumors abounded that Connie Mack's A's were deciphering opponents' signs. Understandably wary, the Giants changed their signs multiple times during the Fall Classic.

- Whether the distraction affected them or not can't be determined, but John McGraw's club lost the Series in six games.

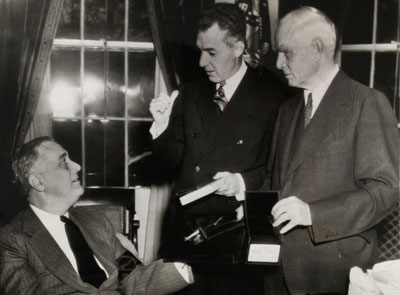

- Afterward, 2B Eddie Collins revealed Philly's secret to American Magazine. There were no binoculars or buzzers. The team's pitchers had become adept at reading the body language of opposing hurlers. Chief Bender, Danny Murphy, Jack Coombs, and Harry Davis became so expert that they could call every pitch made by every pitcher in the league by watching the way he held the ball, the way he delivered it or other little eccentricities. (Sporting News Official Guide)

- Duly warned, pitching staffs now concentrated on masking their pitches.

Leave it to the great star of the time, Ty Cobb, to have the last word. He wrote in the New York Evening News: If a player is smart enough to solve the opposing system of signals he is given due credit. ... [But] the use of field glasses, mirrors and so on, by persons stationed in the bleachers or outside the center field fence ... is reprehensible and should be so regarded.

Reference: The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World, Joshua Prager (2006)

Top of Page

|

The hidden ball trick is a time-honored play that occasionally embarrasses a base runner (and his base coach) and may get a crucial out in a game.

The play has occurred only once in the World Series.

- In Game 2 of the 1907 Fall Classic, 3B Bill Coughlin of the Tigers caught Cubs CF Jimmy Slagle with a hidden ball in the bottom of the first inning. There was one out at the time with player-manager Frank Chance at the plate. The Cubs failed to score in the inning but did win the game 3-1 on their way to four straight. (Game One had been called by darkness after twelve innings.)

Mike Lowell |

One of the funniest - and therefore most embarrassing - hidden ball plays occurred during the 1958 season.

- Billy Gardner of the Orioles was on 2B during a game at old Comiskey Park. White Sox 2B Nellie Fox asked Gardner to step off the bag for a moment so he could clean it. When Gardner did as requested, Fox tagged him with his glove containing the ball!

Among contemporary players, Mike Lowell has pulled the trick at least twice, both at critical junctures in the contests.

- September 15, 2004: While playing 3B for the Marlins, Lowell caught Brian Schneider of the Montreal Expos with two out in the fourth inning and the bases loaded. Lowell ended up with the ball when the previous play ended. After going to the mound to confer with his P, Mike kept the ball and, when Schneider led off the bag, tagged him out.

- August 10, 2005: Lowell struck again. This time the victim was Luis Terrero of the Diamondbacks. Terrero represented the tying run in the eighth inning with the Marlins leading 6-5.

The P must be careful, or he can ruin the trick. If the P is standing or or astride the rubber when the play is attempted, a balk is called.

Continued below ...

|

Hidden Ball Tricks - II

Whitey Lockman

|

Some more hidden-ball stories.

1935-7

- As a boy on the South Side of Chicago, Billy Rogell delivered milk in the off-season to the door of Oscar "Ski" Melillo, a Chicago native who played for the St. Louis Browns. Idolizing Oscar, Rogell would set the bottles down about 6 a.m. and yell up to his hero's bedroom, "Oh, Oscar, good morning, Oscar."

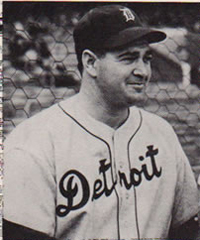

- Time passed, and Billy became the SS of the Detroit Tigers. Melillo now played 2B for the Red Sox.

- Rogell stood at 2B. Oscar grinned over at him.

Remember when you delivered my milk?

Rogell chuckled and unconsciously moved toward his idol.

Bet I woke you many a morning, huh, Oscar?

Melillo replied as he slapped him with the ball:

You sure did. But this makes us even.

May 6, 1951

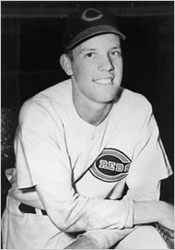

- The Cincinnati Reds hold a 4-3 lead in the bottom of the tenth at the Polo Grounds. Whitey Lockman leads off for the New York Giants with a walk and is sacrificed to second.

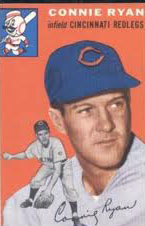

- Reds second-sacker Connie Ryan walks over to Lockman standing on second and asks:

Hey, get off the bag a minute will you, so I can straighten it out?

- Whitey obliged, and Ryan eliminated the potential tying run.

To be continued down the road ...

Reference: "Hidden-Ball Trick Really Has Whiskers,"

John P. Carmichael, Chicago Daily News Service 5/12/51

Bits of Baseball Lore Archive | Top of Page

|

Oscar Melillo

|

World War II's Impact on the Game - I

Ed Barrow

Donald Barnes

Philip Wrigley

Dutch Leonard

Bobo Newsom

Rudy York

Ernie Lombardi

|

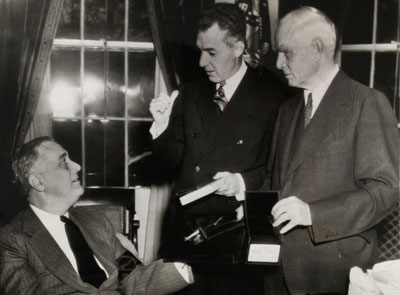

In his "green light" letter, Roosevelt hoped that night games can be extended because it gives an opportunity to the day shift to see a game occasionally.

- This suggestion surprised the owners, the majority of whom opposed night ball in their parks. They had limited teams with lighted fields to seven night games a season, one for each visiting opponent. Yankee GM Ed Barrow went so far as to brand night baseball a passing fad, a wart on the nose of the game, and said it would be frivolous to spend $250,000 to install lights in Yankee Stadium.

- At the owners' meeting right after Pearl Harbor, Donald Barnes of the Browns and Clark Griffith of the Senators requested that their teams be allowed to schedule 14 night games so they could stay afloat financially. The owners reluctantly agreed.

- But after the president's letter, the owners raised the night game limit to 21 for Washington (where the president resided, of course) and 14 for every other team with lights: Reds (first night game 1935), Dodgers ('38), Athletics and Phillies ('39), Indians ('39), White Sox ('39), Giants ('40), Browns and Cardinals ('40), Pirates ('40), and Senators ('41). No additional teams added lights during the war. Cubs owner Philip Wrigley had planned to install lights for the '42 season but after Pearl Harbor donated the materials to the war effort. It would be 46 years before Wrigley Field hosted a night game.

- NL President Ford Frick insisted that raising the limit on night games was temporary - just for the duration of the war.

- A new GM brought night baseball to Yankee Stadium for the '46 season - Larry MacPhail, who had pioneered baseball under the lights while at Cincinnati and Brooklyn.

President Roosevelt receives passes to NL games for the 1942 season

from President Ford Frick and to AL games from Senators owner Clark Griffith. Club owners used the war as an excuse for holding down salaries.

- When Dutch Leonard asked for a raise in 1942 after winning 18 games for the Senators, Griffith turned him down, saying In these war times, with conditions as they are, anybody ought to welcome the same salary as he received last year.

- The Tigers did the Senators one better. They cut the salaries of P Bobo Newsom and 1B Rudy York from $32,500 and $20,000 respectively to $11,000 each. When Newsom complained, he was dealt to Washington.

- When the government imposed controls on salaries and prices later in 1942 to restrain inflation, MLB asked whether they were free to cut players' pay. The government replied that each salary had to fall in a range set by the lowest and highest salaries on the team the previous season. The ruling led to the New York Giants acquiring C Ernie Lombardi, the '42 NL batting champion, from the Boston Braves, whose highest salary in 1942 was $12,500. Lombardi wanted $15,000, which the Braves would gladly have paid but could not under the guidelines. The Giants, however, had paid SS Billy Jurges $17,500 in '42.

- Salary disputes proliferated in '43 and '44. Mort Cooper of the Cardinals, after winning 22 games in '42 and 21 in '43, refused to sign the contract calling for $12,000 for '44. Owner Sam Breadon invoked patriotism to shame Cooper into compliance. Certainly, at a time like this, it is unwise for players who have excused from military service for some reason or another to publicize their dissatisfaction with the contracts which have been sent them. I do not think it makes very good reading for persons who have their boys on the fighting fronts. Cooper signed but held out again in '45.

Patriotic fervor produced other effects.

- The national anthem had been played at each game of the 1918 World Series, which was played early after the government ordered baseball to shut down right after Labor Day. In subsequent seasons, the Star Spangled Banner was played before games on national holidays and at every World Series game. But owners decided to play the anthem at every regular season game during World War II, a custom that continues to this day.

- The 1942 World Series was the first one to be broadcast live to service personnel overseas.

Continued below ...

Reference: Even the Browns: The Zany, True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties,

William B. Mead (1978)

|

World War II's Impact on the Game - II

In September 1943, the major leagues offered to send two teams on tour to entertain the troops in the Pacific Theater.

- Many players volunteered, including all stars like Bucky Walters and Johnny Vander Meer of the Reds, Bob Elliott of the Pirates, Stan Musial of the Cardinals, Yankees Bill Dickey and Charlie Keller, Tex Hughson and Bobby Doerr of the Red Sox, Luke Appling of the White Sox, and Rudy York of the Tigers. The Sporting News implored the players not to make the trip a "vacation or merry-making junket."

- But after all the preparations had been made, the War Department reversed itself and canceled the trip. The stated reason was a shortage of ships and planes. However, the real reason, as reported by Drew Pearson in his syndicated "Washington Merry-Go-Round" column, was that Secretary of War Henry Stimson "felt that the troops would resent the sight of apparently healthy ballplayers not in service uniform and would not realize that each ballplayer of military age had been exempted from the draft because of some physical infirmity."

- A year later, baseball did pull off a smaller excursion. Five groups of 4-5 baseball notables each visited troops in various parts of the world. For example, Musial and Danny Litwhiler of the Cardinals, Dixie Walker of the Dodgers, Hank Borowy of the Yankees, and Pirates manager Frankie Frisch went to the Aleutian Islands to chat with troops.

Baseball became a bone of contention in the conflicts in both the European and Pacific theaters.

- Three Germans posing as U.S. soldiers were exposed by their ignorance of baseball and were shot.

- U.S. airmen in England complained that the Luftwaffe was bombing their baseball diamonds.

- Japanese soldiers on the South Pacific island of New Britain shouted "To hell with Babe Ruth!" as they charged a Marine emplacement. Asked for a comment, Babe said, "I hope every Jap that mentions my name gets shot, and to hell with all Japs anyway."

Meanwhile, every season saw further depletion of ML rosters.

- Some owners wanted to lobby the government for deferment for ballplayers, but Commissioner Landis steadfastly opposed any special treatment. NL President Ford Frick announced, "Baseball is ready, yes eager, to do its duty in national defense. Baseball wants no favors in this respect. It expects no exemptions except such as the authorities may decide to favor it with."

- Still, Senators owner Clark Griffith quietly appointed himself baseball's resident lobbyist. He met with Selective Service director Lewis Hershey once a month, always telling the general "Don't let Landis know I'm seeing you."

- When two of Washington's starting infielders received draft deferments until after the season, many suspected favoritism.

A number of former players who had been retired a year or more were pressed into service as the war continued, and teenagers rushed into the breech as well.

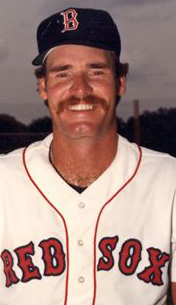

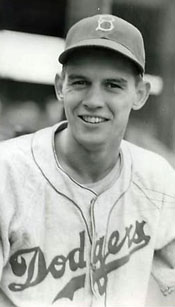

- When the Dodgers lost both 2B Billy Herman and 3B Arky Vaughan to the military for the '44 season, manager Leo Durocher, 38, announced himself as Herman's replacement. But Leo's first fielding chance was a bad throw from 18-year-old rookie SS Gene Mauch. The ball broke Durocher's thumb in two place, sending him back to the dugout.

- Another Dodger, 33-year-old OF Dixie Walker, was tried at 3B, but his throws were so wild that even 6'6" 1B Howie "Steeple" Schultz couldn't reach them. Other infielders that Durocher deployed that service were Tommy Brown, 16, Eddie Miksis, 17, and Eddie Basinski, 21, who had played the violin in high school but not baseball.

- Another teenager, Joe Nuxhall, made his ML debut on June 10, 1944 on the mound for the Reds. He remains the youngest player ever to appear in a major league game: 15 years, 10 months, 10 days. He allowed five hits and two runs in 2/3 of an inning. That was his only appearance that season for a 67.50 ERA. The southpaw would not appear in a ML game again until 1952 at the ripe old age of 23. He compiled a 135-117 record over 16 years.

The ultimate wartime replacement player toiled for the St. Louis Browns in 1945.

- Six-year-old Pete Gray fell off a farmer's wagon and caught his right arm in the spokes. Doctors amputated above the elbow.

- Determined to play baseball despite his disability, Gray learned to hit and throw left-handed and developed an uncanny method of catching the ball in the glove on his left hand, tucking the glove under his armpit, and throwing it back with the same hand.

- After playing semipro ball for a few years, he caught on with his first organized baseball team in 1942, batting .381 in the Canadian-American League.

- His big break came when the Memphis Chicks of the Class A Southern League signed him. Playing regularly in 1943, he hit .299 and began to receive nationwide publicity. Difficult to strike out, Pete perfected the art of drag bunting either down the 3B line or past the P. He also hit many line drives. The next season, he blossomed into a star, batting .333, stealing 63 bases to tie the league record, and leading all outfielders in fielding percentage. As a result, he was voted MVP of the Southern League.

- The Browns, defending AL champions, signed Gray for the '45 season, insisting they did so because of his playing skills, not his ability to draw fans. But the front office pressured Manager Luke Sewell to play Gray more to put fannies in the seats.

- An introverted loner, Pete didn't get along with many of teammates, some of whom considered him a freak who was hurting their chances of repeating as pennant winners.

- Opposing teams pinched their infielders in to discourage his bunts and played the outfield shallow to snag his liners. As a result he hit just .218 in 77 games and stole only five bases.

- Browns 3B Mark Christman recalled years later: Pete did great with what he had. But he cost us the pennant in 1945. We finished third, only six games out. There were an awful lot of ground balls hit to center field. When the kids who hit those balls were pretty good runners, they could keep on going and wind up at second base. I know that cost us eight or ten ball games.

- Gray never again played in the major leagues. He played parts of the '46, '48, and '49 seasons for Toledo, Elmira, and Dallas.

Reference: Even the Browns: The Zany, True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties,

William B. Mead (1978)

|

Leo Durocher

Gene Mauch

Howie Schultz

Tommy Brown

Joe Nuxhall

Pete Gray

|

|