Tip O'Neill

Curt Welch

Sam Barkley

Bill Gleason

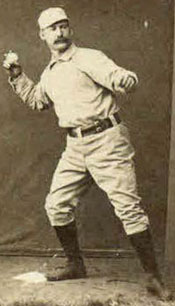

Bob Caruthers

Dave Foutz

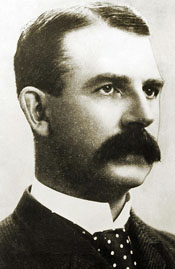

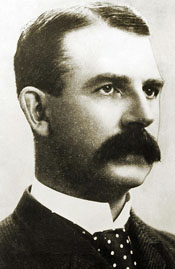

Albert Spalding

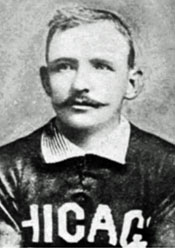

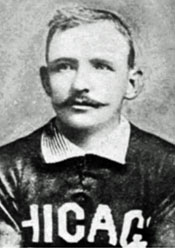

Adrian "Cap" Anson

Yank Robinson

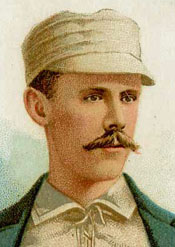

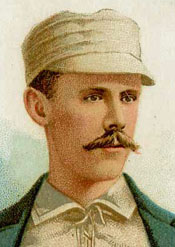

Michael Joseph "King" Kelly

Fred Pfeffer

John Clarkson

Hugh Nicol

Ned Williamson

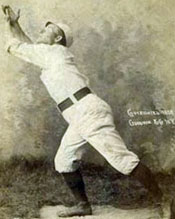

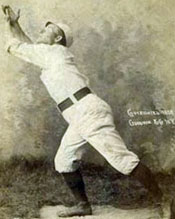

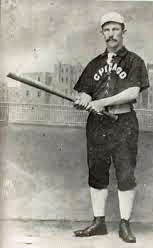

Billy Sunday

Fred Dunlap

William Medart

Jim McCormick

Abner Dalrymple

Tom Burns

|

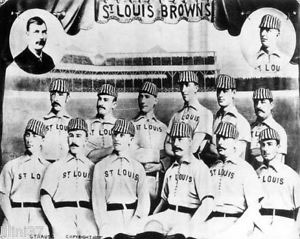

Four Pennants in a Row - 1885

The St. Louis Browns won the American Association championship four straight years from 1885 to 1888.

The Browns became the St. Louis Perfectos in 1899 and the Cardinals the following year.

An excellent judge of talent, Comiskey transformed the Browns from a 4th-place team in '84 to pennant winners the following season.

- OF Tip O'Neill led St. Louis is batting average with a .350 mark, 79 points higher than the second-best performer, OF Curt Welch, one of Comiskey's off-season acquisitions.

- The "dead ball" nature of baseball in 1885 is illustrated by the Browns' extra-base hitting stats:

132 doubles, 57 triples, 17 home runs.

- Welch and another newcomer, 2B Sam Barkley, led the team in two-baggers with 18 each.

- Barkley stood alone atop the triples list with 10.

- O'Neill, Welch, Barkley, and SS Bill Gleason each had three four-baggers.

Another sign that the National Pastime was decidedly different in those days is that three men did all the pitching for the Browns.

- 21-year-old Bob Caruthers, an '84 holdover whom Comiskey moved from the OF, started 53 games and completed them all. His final record: 40-13 with an ERA of 2.07. He threw an incredible 482 innings.

- Dave Foutz, age 28, started 46 games, completing all 46, and also finished another game. Foutz's record: 33-14. Dave also topped the 400 mark in innings pitched by 7 2/3.

- Missouri-native George "Jumbo" McGinnis had been a St. Louis stalwart for three years, compiling a 77-50 record. But he started only 13 times in 1885 and finished 6-6.

Some 1885 rules differed from what we know today.

- The pitching distance was 50'.

- Six balls constituted a walk, down from seven in 1882 and eight before that.

- Overhand pitching had just been legalized in 1884.

- One side of the bat could be flat.

|

|

Few players wore gloves in 1885. They were generally considered unmanly. The first reference to a player wearing a glove was in 1875. Those they did wear were more like work gloves than later day mitts, as shown by these diagrams from an 1885 patent application. Numerous errors were committed as fielders with bare hands or small gloves tried to catch hard grounders and long flies. |

|

The Browns coasted to the pennant by a whopping 16 games over Cincinnati.

- Von der Ahe challenged Albert Spalding, owner of the National League champion Chicago White Stockings, to a series of "world's championship" games.

The Browns were a charter member - along with Chicago - when the National League began in 1876 but dropped out after only two seasons.

The White Stockings became the Chicago Colts in 1890, then the Chicago Orphans in 1898, and finally the Cubs in 1903. So both teams in the 1885 post-season series would change their nicknames and have their old monickers, Browns and White Stockings, picked up by American League teams right after the turn of the century

- Post-season games between the AA and NL champs were not without precedent. In 1882, the Cincinnati Red Stockings and the White Stockings split two games.

Two years later, the AA champion New York Metropolitans challenged the first-place NL team, the Providence Grays, to a three-game set.

The '82 series was cut short when AA president Denny McKnight, who had banned interleague play, threated to expel all the Cincinnati players.

In 1884, Grays ace "Old Hoss" Radbourn, who won 59 games during the season, allowed only four runs in three victories in chilly, late October weather.

- Looking to make some money for themselves and their players, Von der Ahe and Spalding scheduled a twelve-game, seven-city series. After the first game in Chicago, all remaining contests would be held in six Association cities starting with three in St. Louis.

- The egotistical Von der Ahe hoped the series would provide a chance to promote his team, give his league credibility, and enhance his national reputation. Spalding didn't take the challenge nearly as seriously. Nor did White Stockings player-manager Adrian "Cap" Anson, who called the American Association a "beer league" and proclaimed that St. Louis wouldn't finish in the top four of the National League. (Shades of the NFL and AFL in 1966!)

Pitchers feared no hitter more than Anson. As a manager, he employed the hit-and-run, signals, platoons, and the pitching rotation. After a mischievous youth that saw him get kicked out of the high school attached to Notre Dame College, he became a drill sergeant manager who marched his men onto the field in military formation. He laid down many rules, including no drinking. The sobriety requirement was (to quote Shakespeare) "More honor'd in the breach than the observance," especially by his 1885 club during the post-season series.

- To make the competition more interesting, each club put up $500 as a purse that would be divided among the players of the two teams in proportion to the number of games won. But the $1,000 prize to the winners paled in comparison to the money bet by the players.

Caruthers supposedly waved a roll of bills at Anson and proclaimed, I'll bet you $1,000 that the Browns can easily beat your nine. And I'll put this money up as a forfeit.

Anson urged his mates to take the games seriously. But some of his veterans, including P Jim McCormick and hitting stars King Kelly, Ned Williamson, George Gore, and Abner Dalrymple, tired after the long season and unimpressed by the $70 they'd get for winning, wanted to go home. They drank heavily before the games. In fact, Gore was so drunk before the opening game that Anson benched him in favor of Billy Sunday.

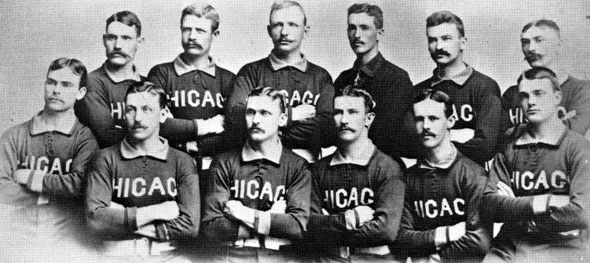

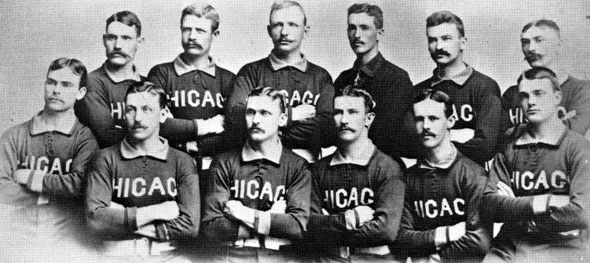

1885 Chicago White Stockings

The Series never made it past Game Seven.

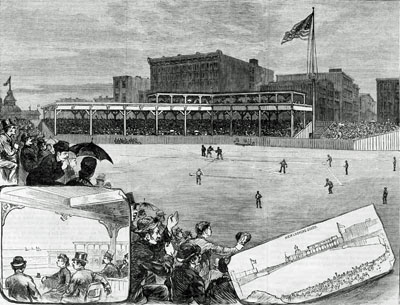

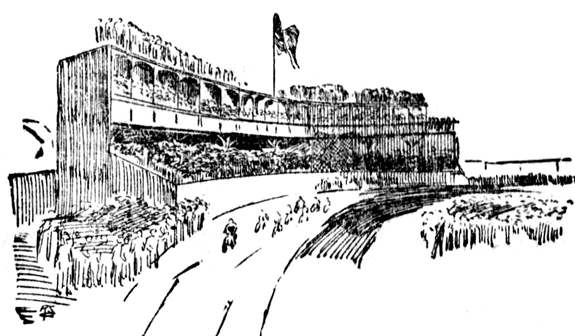

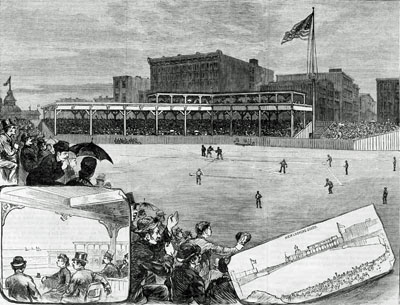

- October 14: Game One was played at the Congress Street Grounds (also known as West Side Park) in Chicago before 2,000 spectators. The entire gate money was given to the Chicago players as a complimentary benefit.

Darkness ended the game after eight innings with the teams tied 5-5.

Prior to the game, contests were held to see who could throw the ball the furthest and run the bases the fastest as well as a foot race pitting the speediest Brown against the swiftest Chicagoan. These competition delayed the first pitch until 3:15.

As the home team, the White Stockings chose to bat first.

Home teams generally chose to bat first to get their licks at the new ball before it began to soften.

West Side Park, Chicago

Chicago sent home a run in the 4th on RF "King" Kelly's single and two errors.

The flamboyant Kelly was one of the best players of his era. If Anson topped the White Stockings in ability, The King ranked a close second. He could play any position, including C, and consistently drew raves for his baserunning skills, including the hook slide which, if he did not originate the technique, he perfected it. Some also credit Kelly with inventing signs between C and P and the hit-and-run.

The handsome, impeccably dressed Irishman had lady friends in every city. One of his traits tested his manager's patience. Cap once said, There's not a man alive who can drink Mike Kelly under the table. The King died at age 36 and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1945.

With darkness approaching, Caruthers hurried his motion in the top of the 8th to complete the game. But the strategy backfired as the White Stockings plated four to pull into a tie. CF George Gore drew a walk and scored on singles by Kelly and Anson, playing 1B like his counterpart, Comiskey. 2B Fred Pfeffer followed with a home run, his sixth of the year.

When Chicago P John Clarkson (53-16) put down St. Louis in the bottom of the inning, the lone umpire, Dave Sullivan, called the game because of darkness.

Why Sullivan was chosen as the arbiter is unknown since he had not officiated any contest that year.

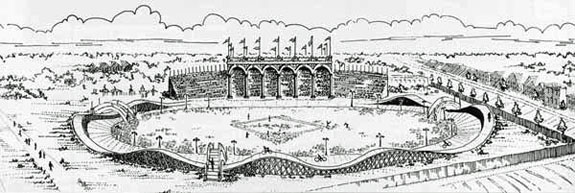

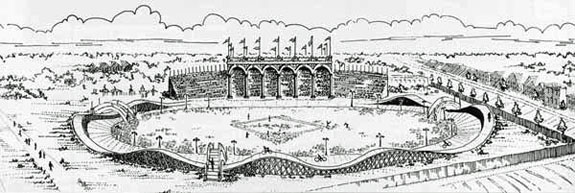

Sportsman's Park, St. Louis

- October 15: Game Two - Sportsman's Park, St. Louis with 3,000 fans.

With both teams adept at umpire-baiting, Sullivan would have had his hands full even if he were competent.

In the 1st inning, he called Kelly out at 2nd on a steal when nearly everybody thought the runner was safe. Two innings later, he angered the other side by declaring foul a hit to RF by Foutz that some thought was at least a foot inside the line. Dave reached 2nd on the play when RF Clarkson bobbled the ball only to be called back to the plate. Since the home team was now victimized, the St. Louis fans roundly denounced Sullivan. When Barkley was called out on a pitch that was clearly too high, the hissing and shouts of "Get another umpire" reached a crescendo.

Matters settled down, and the Browns took a 4-2 lead into the bottom of the 6th. And that's when Sullivan completely lost control.

After Billy Sunday led off with a double to RF and went to 3rd on a passed ball, Kelly hit a grounder to Gleason, who fumbled the ball, then threw to 1st for what looked like the first out as the run scored. But Sullivan, who had looked at home plate expecting a throw there, didn't see the play at 1st and guessed "safe." Amid heckling and cries of "robbery" from the crowd, Comiskey came in from 1B not only to protest the decision but also to demand that Sullivan umpire no longer. The arbiter reacted by going to the players' bench, putting on his coat, and sitting down. But Anson refused to permit a change of umpires. During the long dispute, a man claiming to be the Vice President of the St. Louis club came onto the field and tried to intervene. Finally, Sullivan pulled out his watch and began a two-minute countdown, telling Comiskey he would forfeit the game if the Browns did not return to their position. So Charlie motioned his men back out, and play resumed.

Peter Golenbock described the Browns' player-manager like this: Charlie Comiskey ... was a mild-mannered, cerebral man off the field, but on the field, he could act like a common thug. ... Comiskey would bait umpires and argue every call that went the other way. ... He was a nineteenth-century role model for Leo Durocher and Billy Martin.

Cap Anson was not much better.

Kelly stole 2nd, took 3rd on a wild pitch, and scored on Anson's single to CF. Pfeffer lofted a fly to short RF that Hugh Nicol muffed but recovered to force Anson at 2nd. Pfeffer stole 2nd. Then 3B Ned Williamson hit "a ball which hit outside the foul line but rolled inside before it reached first base." When someone yelled "foul," Comiskey let the ball go. Williamson, after hesitating, hurried to 1st while Pfeffer came home all the way from 2nd. Charlie lit into Sullivan, who claimed it was not he but Anson who called "foul." The Browns' skipper said the ball was foul under American Association rules. So Sullivan changed his call. That enraged Anson, who called Comiskey's bluff by asking for a copy of the rules. When the Browns skipper admitted the AA rule was the same as the NL's the beleaguered umpire reversed his reversal. At that point, Comiskey had had enough and motioned his team off the field. When 200 fans stormed from the stands, the White Stockings picked up bats to defend themselves. Police came to the rescue and led the visitors from the grounds. Another officer escorted Sullivan to safety, some fans abusing the ump the entire way.

When Sullivan returned to his hotel room, he proclaimed the game a forfeit to Chicago, 9-0.

The Browns disputed the decision, saying it should have been made at the grounds.

- October 16: Game Three - Sportsman's Park, St. Louis

The Browns fired Sullivan before the next game and replaced him with a local man named Harry McCaffrey. Presumably Anson approved the substitution, but he may not have known that McCaffrey had been a Browns' outfielder two seasons earlier.

The fired-up St. Louisans struck for five in the 1st off Clarkson and coasted to a 7-4 victory to even the Series at 1-1-1.

- October 17: Game Four - Sportsman's Park, St. Louis

The first pitch was delayed 45 minutes because Anson refused to accept McCaffrey. Apparently, Cap discovered Harry's past affiliation with the home club. After much persuasion from Comiskey, Anson finally agreed to let McCaffrey work. However, when asked to take the field again, the former Brown refused. I wasn't good enough for Chicago last night, and you can't have me today for any price. Fred Dunlap, a player for the St. Louis Maroons of the Union Association, also declined an invitation to umpire. Finally, William Medart, the treasurer of a local pulley company, stepped forward. He had been a National League umpire in 1876-77. However, he had since become an ardent Browns fan.

Chicago's Jim McCormick and Foutz engaged in a pitcher's duel that was marred by Medart's biased umpiring. After Abner Dalrymple clouted a HR to put the White Stockings ahead 2-1 in the 5th, the hometown ump suspiciously called Chicago's Tom Burns out on a pickoff play in the same inning.

St. Louis tied the score in the bottom of the 8th on Caruthers' single, then took the lead when Bill Gleason raced home all the way from 2nd on Welch's bounder to 3rd.

After the first batter was retired in the 9th, Barkley booted Tom Burns's grounder. McCormick then hit a weak popup behind 1B. Comiskey let the ball slip through his hands. That put runners on 1st and 2nd. Frustrated, Charlie touched McCormick with the ball when the batter had one foot on the bag. Medart surprised everyone and disgusted even the Browns' fans by calling McCormick out. The White Stockings went berserk. McCormick charged the ump, but Anson raced out from the bench to hold him off. Sunday came out with fists flying and questioned Medart's integrity before Kelly restrained him. When play resumed, Foutz retired the last batter to seal the 3-2 victory.

Billy Sunday underwent a religious conversion a few years later and left baseball to become an evangelist. Eventually, he became the Billy Graham of his day, attracting large crowds

in cities across the nation. A strong supporter of prohibition, his preaching played a significant role in the adoption of the 18th Amendment in 1919.

The St. Louis Globe-Democrat proclaimed Game 4 one of the most exciting that has taken place at Sportsman's Park this season. The games in the Mound City averaged 3,000 fans. Unfortunately, the Series now took four days off. If the remaining games had been played in Chicago, crowds may have flocked to the park. Instead, they were scheduled for cities with no horse in the race.

During the break, the Browns played exhibitions against the Maroons. Then they took the train to Pittsburgh.

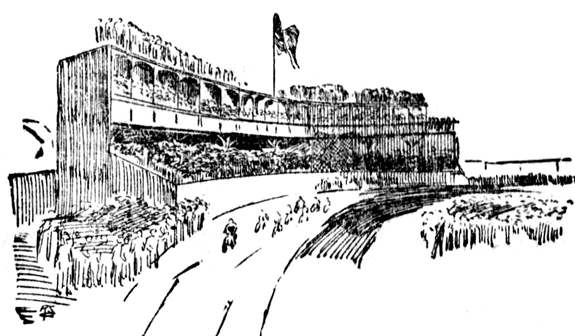

Recreation Park, Pittsburgh

- October 22: Game Five - Recreation Park, Pittsburgh

Anson chose the ump for the rest of the Series - "Honest John" Kelly. He had been a major-league umpire for four years in both leagues.

Chicago won easily 9-2, Clarkson outpitching Foutz before 500 chilly fans.

Newspaper articles complained that the games were played "listlessly" without the passion of Games Two and Four. Honest John ended the game after seven innings because of darkness.

Noting the indifference of Pittsburgh fans, Von der Ahe wired Spalding and suggested the Series end after two more games. Chris also cited the cold and unfavorable weather. Spalding agreed. So the games scheduled for Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn were cancelled

League Park, Cincinnati

- October 23: Game Six - League Park, Cincinnati

Before the game began, umpire Kelly told the 1500 fans that the teams had agreed that Game Seven would be the final one.

McCormick held the Browns to two hits

in another Chicago rout by the same score as Game Five, 9-2, despite committing ten errors.

The next day's St. Louis Post-Dispatch criticized the cancellation of the last four games of the Series. It is to be regretted that Von der Ahe and Spalding came to this conclusion, as the games between these clubs that have been played so far have been closely contested ones, and whether the Chicagos or Browns win today's game, it will still leave the question as to which club is superior entirely in the dark.

- October 24: Game Seven - League Park, Cincinnati

Before the game, Kelly told the surprisingly good crowd of 1200 that the game would decide the "championship of the world" (as the wire report on the game put it). Anson had acquiesced to the Browns' contention that Game Two did not count as a Chicago victory. Cap may have done that not only to stimulate attendance but also because he had every confidence that his club would continue the dominant play of the previous two games.

Anson told the press: We will not evenclaim the forfeited game. We each have two victories now, and the winner of today's game will be the winner of the series.

However, the Chicago manager changed his pitching plans when Clarkson, his preferred starter for the finale, arrived at the park five minutes late (and perhaps inebriated). Ever the disciplinarian, Cap instead forced McCormick to hurl for the second straight day. On the other side, Foutz worked with one day's rest.

The Chicagoans started fast with two in the 1st on hits by Sunday and Kelly and an error on Barkley. But the Browns charged back against the weary McCormick - four in the 3rd and 6 in the 4th. A day after surrendering only two hits, Mac was touched for twelve. Add some poor defense and you have a 13-4 St. Louis romp. Welch started the 3rd inning uprising with a triple and continued home on Dalrymple's error. Barkley and Comiskey smacked hits, and the former scored when Robinson forced Charlie. Robby stole 2nd and eventually came home on a passed ball. The Browns rapped five hits in the 4th but more bad fielding made only two of the six runs earned. The game was halted after the top of the 7th because of darkness.

The seven-game set ended with more errors than hits, 102-96.

Now, of course, Anson regretted his pregame agreement.

A special committee ruled the series a tie.

Both owners publicly acknowledged the decision, thereby avoiding paying the players their share of the $1,000 prize money. When Von der Ahe proclaimed his team the winner, Chicago President Spalding protested, implying that he never considered the games anything other than exhibitions. Does anyone suppose that if there had been so much at stake that I should have consented to the games being played in American Association cities upon their grounds and under the authority of their umpires?

|

References: Chris Von Der Ahe and the St. Louis Browns, J. Thomas Hetrick (1999)

The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns, Peter Golenbock (2000)

"The Top Twenty Games in 19th Century St.Louis Baseball History: #19," thisgameofgames.blogspot.com (9/22/2012)

Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis, Jon David Cash (2011)

The Baseball Timeline, Burt Solomon (2001)

|

|