|

|

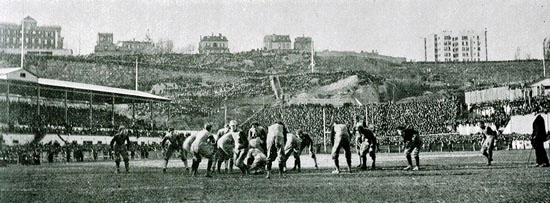

After all the hoopla of the previous days, it was time for the two undefeated rivals to play football at Manhattan Field.

- Many New York churches held their Thanksgiving services an hour earlier.

- Fifth Avenue mansions were draped in the school colors. The Vanderbilts and Whitneys flew blue banners with a white Y while orange flags with a black P proclaimed the allegiance of the Sloanes, Alexanders, and Scribners.

- Fans heading to the game wore appropriate fall clothing with both men and women sporting ribbons and even flowers of the appropriate colors. Many of the gentlemen twirled canes wrapped in school-color ribbons.

- Every vehicle that could hold a passenger was commandeered for the ride to the Polo Grounds, twenty men at a time balanced perilously atop omnibuses from Washington Square to Harlem. The buses were "draped from top to hub with festooned colors," and they were stocked with bourbon, champagne, sandwiches, whole cold salmon, and roasted chickens" - a moving tailgate party. (Sally Jenkins, The Real All Americans: The Team That Changed a Game, a People, a Nation)

- In the final hours before the game, trains arrived every two minutes packed with hundreds of fans bound for Manhattan Field.

- Vendors sold banners, flags, ribbons, buttons, and horns.

- Scalpers charged an outrageous $7 to $15 for desirable seats.

- A flurry of betting that morning drove the odds down to $100 to $20. Odds of 2 to 1 were quoted at noon that Princeton would not score. When a man bet $10 against $100 that Yale would not score, all who heard it roared with laughter.

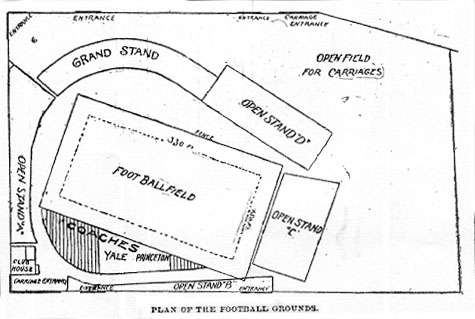

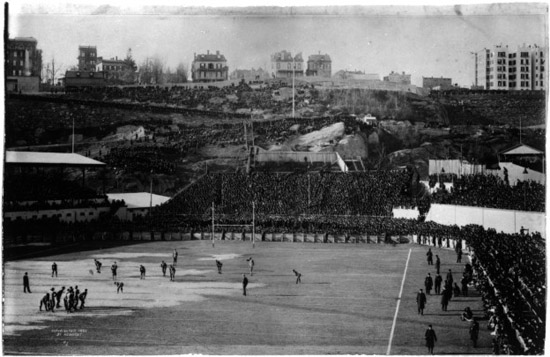

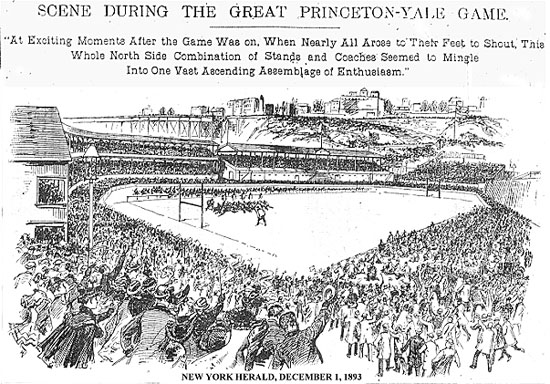

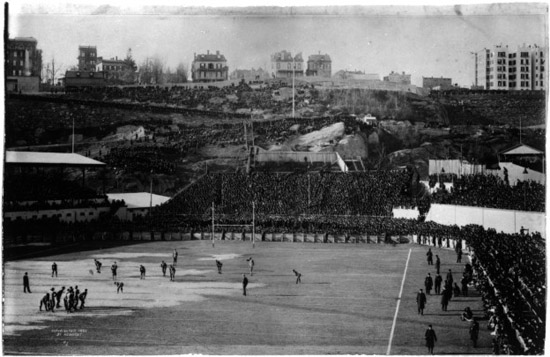

A crowd estimated at 50,000, the largest and most fashionable that ever witnessed a football game (according to The Daily Princetonian), filled the stands and surrounding areas on a nice late fall day. When they couldn't find a seat, they stood wherever they could find room, some circling the field.

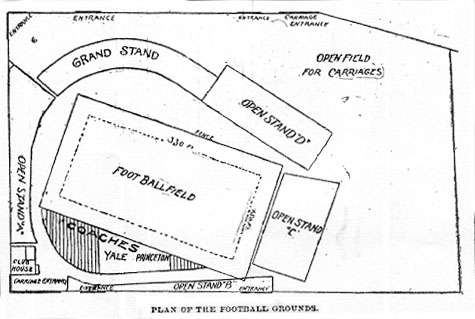

- The northern end of the field consisted of covered box seats. On the edge of the field below those were carriages and Tally-hos with fans sitting on the roofs dining on a Thanksgiving meal of chicken, cranberry sauce, and mince pie, all washed down with champagne.

- Thousands more who couldn't get into the stadium sat on Coogan's Bluff, also known as Deadhead Hill (a "deadhead" being a freeloader), and looked down on the field. Hundreds even climbed onto the 155th Street viaduct.

Those arriving at the top of Coogan's Bluff expecting to watch the game for free were met with a rude surprise. An entrepeneur had paid Coogan $2000 (about $50,000 today) to rent his land. He had stretched ropes around the perimeter and charged 50 cents a head admission. Well more than the 4000 people needed to break even paid to sit on the rocks and watch the ants on the field below.

- Princeton students outnumbered Yalies, and a number of Columbia lads joined the chorus for the Tigers.

- The game received unprecedented media coverage. The New York Sun sent 17 reporters to the game and would devote 20% of its next day issue to the coverage of all aspects of the contest.

- The New York Times report included this telltale passage: The good-natured crowd found much to amuse it while waiting for the players. A Titan of a darky, wearing black satin trousers and orange satin coat and waistcoat, was heartily cheered by Princetonians as he promenaded in front of the stands.

As kickoff time approached, the weather improved. The sun peeked out and the temperature rose into the high 40s.

- Underdog Princeton entered the field first amid deafening and prolonged cheers from its side. C David Balliet was so excited that he did cartwheels. Three other players did a rehearsed dance that ended with all burying their noses in the grass.

- Yale entered in a more professional, confident manner as befitted a team that had won 37 in a row by a combined score of 1,285 to 6. No conquering army returning home ever received a grander reception than was awarded to those hardy Yale champions ...

- The members of both teams wore snug-fitting canvas jackets that laced up the front atop their uniforms. Almost no one wore any kind of headgear. Shoulder pads were sewn into the jerseys. Canvas football pants contained knee and thigh pads. A few 1893 gridders wore a nose guard, usually after suffering a break to the sniffer. Some wore the new shin guards made of cork and covered with leather or canvas

The teams warmed up by punting and passing until 2:16 PM when the referee chosen by the captains of the two teams, Dr. Brooks of Harvard, and the umpire, Dr. Dashiell of Lehigh, called the captains together.

- "Doggie" Trenchard of Princeton refused to look at his counterpart, Frank Hinkey, until the coin was flipped. Then he stared his rival in the eye and won the toss.

- With no substantial wind, Trenchard took the ball. The Bulldogs chose to defend the west goal to have the lazy breeze at their backs during the first of the two 45-minute halves.

According to the 1893 rules: The umpire is the judge for the players, and his decision is final regarding fouls and unfair tactics. The referee is judge for the ball, and his decision is final in all points not covered by the umpire. Both umpire and referee shall use whistles to indicate cessation of play, or any one inside the ropes. If such coaching occur he shall warn the offender, and upon the second offense must have him sent behind the ropes for the remainder of the game.

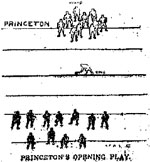

Princeton prepares to kickoff toward Deadhead Hill. There was no kickoff as we know it today. Instead, Princeton put the ball in play from midfield, which was the 55 (as it still is in Canada).

- The "kickoff" was effected by a player touching the ball with his foot, picking it up, and running behind his interference or passing the ball backwards to another player.

The kicker could also boot the ball to the opponents.

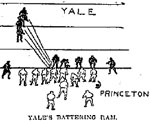

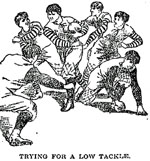

- As can be seen in the picture above, Princeton employed the new flying wedge formation. While one man (the "kicker") leaned over the ball, his ten teammates lined up about 10y behind the starting line in a V shape, the point toward the defense.

- The defense had to remain behind the 10y restraining line until the ball was "kicked," but the offensive team could start before the "kick."

- The wedge started running toward the defense. The kicker waited until the last moment before "kicking off." He grabbed the ball and tossed to one of the advancing players. The ball carrier followed the wedge toward the opponent's weakest link. The "flyers" crashed into the defense with terrific force, often injuring the unfortunate player at the vortex of the attack.

- In this case, Philip King carried for Princeton for 22y.

The Flying Wedge had been invented just the year before by Lorin F. Deland, who taught it to the Harvard team. An independently wealthy Bostonian, Deland was not a college graduate but a leading advertising expert as well as a chess master and military historian. One of his many avocations was inventing football tactics.

Harvard used the new formation in its annual clash with Yale in '92.

The wedge quickly spread to other teams for the 1893 season. Since there was no minimum number of offensive players on the line of scrimmage and no prohibition against backfield men moving forward at the snap, the wedge became a standard running formation as well.

However, the ploy became a victim of its own success. The tactic was outlawed before the 1894 season because of its brutality at a time when football was under siege throughout the country because of its many injuries, including fatalities.

Princeton failed to take advantage of its excellent field position.

- C Balliett snapped back poorly, and his opposite number and good friend, Philip Stillman, fell on the pigskin.

- After G Arthur Wheeler tackled LHB Samuel Thorne for a 5y loss, FB Frank Butterworth punted to Princeton's 45.

- Old Nassau's backs made good gains on three straight plays, but the Tigers lost the ball because of an "off side" play. The same infraction by the Eli gave possession right back.

"Old Nassau" was Princeton's anthem since 1859. The name came from Nassau Hall, built in 1756 and named after King William III of the House of Orange-Nassau. At the time, it was the largest college building in North America and served briefly as the capitol of the United States when the Continental Congress convened there in the summer of 1783.

- The Tigers pulled off one of the finest plays of the game. RHB Franklin Morse took QB King's pitchout on the dead run and shot around J. C. Greenway's end behind "superb interference" by King, Lea, and Trenchard. Butterworth made a TD-saving tackle 35y down the field. However, when two straight plays failed to gain the necessary 5y for a first down, Princeton punted on its 3rd and last down to the 8.

- After gaining three straight first downs with the flying wedge, Yale punted to midfield. Morse galloped for 10y, but the Jerseymen soon ran out of downs.

- In general, Princeton's offense attacked the Bulldog tackles and ends while the heavier Eli more often pushed up the middle.

- Also, teams often punted on first or second down deep in their own territory. Fumbles were common, and an offensive penalty gave the ball to the opponent at the spot of the foul. Futhermore, field goals counted for 5 points to only 4 for touchdowns. So the general wisdom was that it was better for the enemy to possess the ball in his territory than for you to have it near your own goal line.

- Yale pulled a trick play they would use several times during the afternoon. The champions drew back as if to work the wedge but suddenly the V opened to clear space for Butterworth to punt. The object was to draw the backs in to defend the run, leaving no one back to receive the kick. But Butterworth's boot traveled only 25y, giving FB J. R. Blake the opportunity to run under it at the Princeton 40. The ball, Blake, and Hinkey racing downfield in coverage all came together with a bang. The men met head to head, and both dropped to the ground as if felled with an axe. Hinkey received a terrible gash in the head and blood flowed down his face from his right ear (the lobe of which had been torn from his head). Time was granted for medical personnel to attend to the injured player. If he could not return after five minutes, he was out for the remainder of the fray. But Yale fans breathed a sigh of relief when their captain "pluckily" returned to his LE position after the wound was dressed.

Supposedly, when the "157-pound dynamo" returned to the huddle, he gathered his teammates and said, Come, boys, let us get to work.

- Action was frequently interrupted when, after a scrimmage, one man would not get up with the other. Surgeons, trainers, and coaches rushed out to care for the injured player. Substitutes ran onto the field with blankets to put around the shoulders of the regulars to ward off the cold during the wait. The groups of men walking around with blankets gracefully draped about them made a picturesque scene. The long, matter hair of some completed the resemblance to Indian chiefs. (The New York Times) In every case except one, the felled warrior got up and continued in the game.

- Princeton tried some razzle-dazzle, a "double pass" ("double lateral" in today's lingo), but RHB Richard Armstrong thwarted the attempt. So Blake punted, and Yale took over after 5y was marked off for interference with the receiver.

- Butterworth then ripped off Yale's longest run of the day. Several times he is tackled but by excellent warding off keeps his feet till he has placed the ball 35y nearer Princeton's goal. But on 2nd-and-5, the umpire detected a Bulldog holding and awarded the ball to the opponent at their 30. But Princeton preferred Yale to have the ball in its territory. Butterworth returned Blake's punt to his 20 with 5y tacked on for interference with the catch.

- Following Yale's return punt, Princeton had the ball on their 25. By short rushes and a revolving wedge they work the game well into Eli territory before losing the ball ... Ward and Morse alternated toting the leather as Nassau aimed its thrust at LT Fred Murphy and LG James McCrea for steady gains. Along the way, Hinkey's wound reopened, and he bled profusely until time was taken for doctors to redress his head.

The "revolving wedge" took advantage of the fact that no minimum number of offensive players was required on the line of scrimmage. The offense lined up in the shape of a wedge. But when the ball was snapped, the wedge rolled to one side or the other.

The popularity - and peril - of the flying wedge would lead Walter Camp, the game's rules expert, to make two proposals. First, at least seven offensive players must line up at the scrimmage line and, second, no backfield man could be moved forward when the ball was snapped.

- When Yale punted to the 45, the Tigers started another assault on the enemy goal line. By means of wedges on the tackles, including several 15y gains, the onslaught reached the 4.

The Princeton fans near the goal line began chanting, Four, four, four yards more!

The cheer quickly spread throughout the stadium.

But the defense made a stand there, holding Princeton to 3y on three downs, on two of which the Tigers used a "double flying wedge" their coachers had invented for this game. But an off-side penalty allowed Nassau to keep the ball. Given new set of downs, Princeton used a "push play." The Tigers massed behind LHB William Ward and shoved him between Murphy and McRea by brute force over the goal for a 4-point TD. The Princeton sideline did handstands, their chins in the hands and their elbows in the mud, and the rest of their bodies in the air, kicking and dancing with ecstacy. Their joy was understandable. It was the first time Princeton had scored on Yale since 1889!

The Daily Princetonian explained what happened next: "King punts the ball out to Trenchard directly in front of the goal posts and also kicks the goal." The conversion added two points. Princeton 6 Yale 0

After scoring the touchdown, Princeton had two choices for the "try-at-goal."

1. The player who scores makes a mark on the goal line as he crosses it

and, after bringing the ball out in a straight line to a distance he thinks proper, holds it for another on his side to attempt a placekick between the two uprights and above the cross bar of the goal post located on the goal line. The defenders must stay behind the goal line until the ball touches the ground.

2. The more complicated method, called a "Try by a Punt-Out," was used when the touchdown was made near either sideline (as was the case for Princeton). A player on the scoring team makes the mark on the goal line where the touchdown was scored, then moves back from the line into what is today called the "end zone." His teammates gather not less than 5y on the other side of the goal line. The first player then punts the ball to one of his teammates for a fair catch, hopefully right in front of the goal posts. The man who catches the ball makes a mark with his heel as he catches the ball and that determines the spot of the placekick.

- A few plays before the TD, Yale LHB Samuel Thorne had to be carried from the field. Hart substituted for him. The onus to gain yardage would fall even more on Butterworth now.

- Armstrong took the kickoff and gained 8. Butterworth was sent into the line repeatedly for short advances for two first downs before the Dogs finally relinquished possession on the Princeton 25. One reporter's comment on the Princeton LE summarized the viciousness of the play. The left side of Brown's face looked as if he had been hit with a mallet, and there was much more color around his eye than there was in it.

- "The revolving wedge is used successfully" as the Tigers moved 20y before losing the ball on an off-side play.

- Butterworth again rammed into the line several times to the 25 until he lost the ball on a fumble.

- Blake punted to the center of the field. Neither side was able to make significant gains before the half ended with Princeton in possession on her 45.

75 miles away in New Haven,

a local telephone company had mounted a special scoreboard outside its offices. The results of each play were telegraphed from Manhattan and the back and forth progress of the ball was displayed via a crude system using puppets suspended on a wire between two goalposts. The hundreds of people watching from the street fell silent when the Princeton puppet with the ball moved across the Yale goal line.

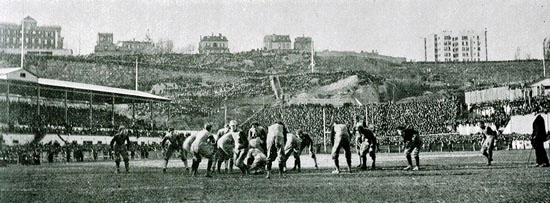

Ground level view of the action After the 15-minute break, it was Yale's turn to use the flying wedge to start the second half.

- At 3:55 PM, Hart took the ball for a gain of 18y. Butterworth gained 5 through LT. On his next effort, Frank fumbled, and it was Princeton's ball. But not so fast, my friend. Holding on the Tigers gave he ball back to the Eli. Armstrong tried Trenchard's end to no avail. So Butterworth punted to the 20.

- Blake booted the ball right back. The noise was so deafening that [QB] Adee repeated his signals each time before a play was made. Wheeler threw Hart for a yard loss. Then LT Augustus Holly and LE Harry Brown dropped Butterworth for no gain to turn the ball over to Princeton.

- When the Tigers were guilty of holding on their third play, the ball was brought back to the line of scrimmage and awarded to Yale.

- Wheeler and Holly continued their stellar defensive play, stopping Butterworth in his tracks. So Frank punted to the 20. Blake kicked back out right away. The strategy worked because RT Langdon Lea broke through and tackled Hart behind the line. The Tigers took the ball back three plays later in a much more favorable position than when they received the punt.

- Ward bolted 8y behind Wheeler's block. Morse added 3 more with 5 extra tacked on for offside. "A mass play against the centre" (probably the flying wedge) yielded 2y, but the drive bogged down and the Eli took over.

- "The Yale backs cannot gain owing to sharp tackling in Princeton's line ..." So Butterworth punted to King, who lost 5y thanks to Greenway's tackle.

- After "slight advances by Morse and Ward," Blake exercised his punting skills again to the Bulldog 40.

- When Old Nassau got the ball back, Morse and Lea make good gains by sharp rushes, and on a long pass from Trenchard, Morse makes a twenty-five yard run [some say 40y] around the right end ... Once again, Bloodworth saved a TD when he pushed the runner out of bounds. The surprise play put the ball on the Yale 35. The "long pass" had to be sideways since forward passing was prohibited. Morse and Wheeler made further gains until the dreaded off-side penalty gave the ball to Yale.

- Butterworth pushed his way through the center for 4. With only 1y to go for a first down, Frank nevertheless punted out of bounds near midfield.

- Play went back and forth in a similar fashion, Princeton constantly gaining more ground than the Eli, especially with their "mass plays on Yale's tackles," but not enough to score again. Yale's only resource is to punt, claimed The Daily Princetonian.

- On one of Princeton's plays, the ball is passed to Blake who makes for the centre, but passes to King, who runs around the end for twenty yards. Three more short gains produced a first down at the 5. But Stillman spearheaded the defense, and Eli took over on downs.

- With the prevalent strategy in such situations being to "punt out" as far as possible, Butterworth unleashed his longest kick of the day, over the heads of the Princeton backs to the 50.

- The Tigers then started another march as Wheeler broke though the center for 15, and Ward got 15 more around LE. Wheeler gained 10 and Morse 8 against the exhausted defense. Soon the ball was on the 10. Out of downs, Blake tried a dropkick for a 5-point FG, but the spheroid spiraled low and wide across the goal line.

- It now becomes so dark that it is with difficulty that the players are distinguished. Starting from the 25, Butterworth gained 4, but Hart lost ground to force another punt.

- The Men of Nassau mounted one more attempt to score and once more reached the 5 only to see Yale again repel the attack. Hart and Butterfield advanced to the 15 when time was called a little after 5 PM.

Princeton fans rushed the field and surrounded their heroes, pushing through dejected Eli partisans in the way.

- However, the Tiger team pushed through the throng to their dressing room.

- Fans pounded on the doors and windows as the players went crazy among themselves.

- At the urging of a coacher, the bloody, muddy warriors paused to sing the school's anthem.

- In the Yale locker room, battered players lay stunned on benches, some "sobbing like schoolgirls."

Hundreds awaited each team at its hotel.

- One report described the return of the Men of Eli to the Fifth Avenue Hotel after the school's first loss since 1890.

About the entrance to the hotel were perhaps 500 people waiting to see what a defeated Yale team looked like. ...

But they never saw a more woe-begone, used-up, pale-faced, bruised and bloodied lot of respectable, healthy, sane young men before. One by one the players crawled down off the coach and passed into the hotel through the alley made by police through the crowd. Two of the players had to be helped, half carried by substitutes. The men had come directly from the field and were in their battle clothes. Their faces were muddy and marked with bloody streaks; their sweaters were stained and reddened, their heads a mass of tangled hair. In their dilapidated condition, marked with defeat, they did not look the strong, powerful, young giants that had driven away from the hotel so full of confidence and sure of victory earlier in the day.

- A different scene took place at the Murray Hill Hotel. ... the Princeton eleven ... did not arrive until 7 o'clock. They had taken time to wash away the marks of the game, and came in dressed in their usual clothes. ... there were two or three hundred wearers of the orange and black there to greet their team. As they came up the steps into the lobby, the cheering began. Louder and louder and more enthusiastic. ... Each individual player was greeted by the warm handshake of his friends, and was clapped on the back and praised and flattered and petted. Later, a dinner was given to the team.

- RG Knox Taylor told a reporter, It wasn't an afternoon tea by a long shot, but it's all the better to think over because the Yale men did play so well.

- Each squad spent the night and returned to campus the next day.

- At the Princeton campus, jubilant students rang the college bell for four straight hours. Townspeople joined in the celebration. The throng paraded to the homes of professors and administrators and demanded speeches.

New York's finest were determined to curb the revelry that had become traditional following the Thanksgiving clash.

- One writer summarized what had happened in year's past. Theatregoers were driven out of playhouses and players howled off the stage by the wild eyed raucous voiced collegians who had tackled so many flying wedges of beer and other "knockers out" that they didn't know where they were at.

- But after numerous complaints from residents and proprietors, the police were everywhere, especially in the "Tenderloin" precinct, and pounced at the slightest intimation of frivolity from yelling at street corners to refusing to move when requested. It was a night of terror. Broadway was promenaded by silent hosts of badly scared men and women who had gone forth to see a "racket" and found nothing but dead men's bones. College men who had drunk deep of various brands of fuel oil, and therefore were incapable of realizing the actual gravity of the situation, were taken from the thoroughfare by brawny detectives and railroaded to oblivion.

- Princeton fans traveling downtown from the game on the elevated train exited at 33rd Street for a parade down Broadway. At 30th, they gave a cheer for the Orange and Black as the coach carrying the Yale team went by. Several plainclothes detectives appeared, grabbed four leaders of the parade, and dragged them to the police station.

- At one theater, the police hustled five unruly Princeton students from a private box. The action roused the ire of the other students from both schools who made up the majority of the audience. The result was a pandemonium of yells and hisses so persistent and protracted that the performance could not go on for some time.

Meanwhile, the Princeton bettors eagerly collected their winnings.

- An estimated $100,000 ($2.5M in today's currency) changed hands.

- Several Yale men on Wall Street lost thousands in bets with colleagues.

The game earned $13,000 for each school, an amount equivalent in buying power to over $300,000 today.

The New York Herald decried the football spectacle as a ruination of a national feast.

Thanksgiving Day is no longer a solemn festival to God for mercies given. It is a holiday granted by the State and the Nation to see a game of football. The kicker now is king and the people bow down to him. The gory nosed tackler, hero of a hundred scrimmages and half as many wrecked wedges, is the idol of the hour. With swollen face and bleeding head, daubed from crown to sole with the mud of Manhattan Field, he stands triumphant amid the cheers of thousands. What matters that the purpose of the day is perverted, that church is foregone, that family reunion is neglected, that dinner is delayed if not forgot. Has not Princeton played a mighty game with Yale and has not Princeton won? This is the modern Thanksgiving Day.

References: The Opening Kickoff: The Tumultuous Birth of a Football Nation,

Dave Revsine (2014)

The American Football Trilogy: The Founding Documents of the Gridiron Game, Walter Camp & Amos Alonzo Stagg, Lorin F. Deland & Henry L. Williams (2010)

|