|

What If?

The April 17, 2017 issue of Sports Illustrated had this interesting piece.

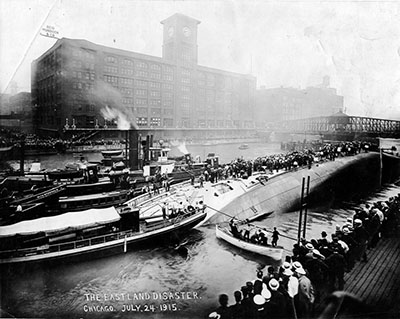

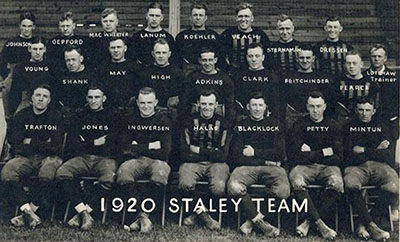

Early on the morning of July 24, 1916, more than 2,500 Western Electric employees boarded the SS Eastland tour ship outside Chicago for a short trip across Lake Michigan to the company's summer picnic in Michigan City, Ind. Arriving late to the port that morning was 20-year-old George Halas, a summer hire at the telephone manufacturer who had planned to play in the company baseball game that day. Instead, he arrived at the Clark Street port to find the top-heavy steamer had rolled over in the Chicago River, killing 844 passengers.   Howell Put Huff in a Huff The Game of Their Lives, by Dave Klein (1976)

Hall of Fame LB Sam Huff recalls his introduction to pro football. So the Giants drafted me [1956] ... because of Al DeRogatis. We (West Virginia) were playing against North Carolina State, and DeRogatis came down to scout Bruce Bosley. And he saw me play. DeRo said he liked Bosley, but he liked Huff just as well.

The Giants drafted me ... but they never did call me before, which I thought was odd. ... I got to training cmp ... and the Giant players at that time really treated the rookies bad. I'll never forget it. They wouldn't even talk to you. I didn't like it. I thought [head coach] Jim Lee Howell picked on the rookies ... he'd yell at you, scream at you, shout at you ... and I just didn't feel comfortable. I was running as fast as I could go, always had great pride in my speed, and hell, I was outrunning everybody else my size, and he's still yelling at me. I was on defense and [Don] Chandler was on offense, and I had a tremendous scrimmage. As a matter of fact, we won because Chandler was punting and I slipped the center ... I was always great at that ... and nobody touched me, and I took the ball right off his foot and went 65y for a touchdown. And we won. Howell said we would have a day off if we won. And do you know he made me practice the net day? To me, as a 21-year-old kid, that wasn't fair. I was down on Jim Lee Howell. I just couldn't understand it. So I went to [kicker] Don Chandler ... he was a rookie, too ... and I said, "I don't feel welcome at all, let's get the hell out of here." He said, "Okay, let's go." I said, "I'm not kidding. I'm ready to go." But we had to turn in our notebooks, and we go downstairs to the coaches' office ... well, [offensive coordinator Vince] Lombardi used to share a room with Jim Lee Howell, and Howell wasn't there but Lombardi was, on the bed, sleeping. We walk over and shake him, and he wakes up and says, "What the hell do you want?" and we said, "Coach, we quit." Well, I'm telling you, I never heard such carrying-on in my life. He scared Chandler to death, he ran. I couldn't get out ... I had a bad knee. But he's calling us cowards and s.o.b.'s and everything ... and I said, "Coach, you can call me anything you want, but I just can't take this any more." And he said, "Dammit, we've got so much time invested in you ... you can make this team, all you've got to do is stick it out." And I said, "No, I just don't like it, and I'm not going to hack it." And I leave and I go upstairs and pack my suitcase. And there was this other rookie ... I forget his name, but he was from Ohio State ... and he had a car ... he was going to drive us to the airport. But Ed Kolman, who was the line coach, he came into my room, and he said, "Sam, I'd like to talk to you a little." Okay, fine. But I'm still packing, and he asks me why I'm leaving. I said, "Coach, I'll tell you. It's not the fooball. I can play football. First of all, I'm homesick. And next, it's Jim Lee Howell, and he's just on me so much I can't take it. I really can't. I had pride in my attitude here. I'm running and I'm struggling and he's still on my back, and I don't need it. So I'm getting out. And Ed said, "I'll tell you what. You stay, and I think you can be one of the great ballplayers in this game. And if you stay, he won't say anything else to you. Stick it out, and you won't be sorry." Well, I thought about that. Then I told him, "Okay, if you promise me he'll leave me alone, then I'll stay." So I went to Chandler to tell him I was staying, but he was made because nobody came to talk to him. He said he was still going, and I couldn't talk him out of it. So we all went to the airport, me and Babe and this kid from Ohio State. And we're sitting there, and here he comes, Lombardi. I mean, Lombardi just loved Chandler, and lucky it was such a small airport, only one flight a day. To Lombardi's dying day, Don Chandler was one of his favorite people. He even traded for him after he got out to Green Bay. And Howell left me alone after that, and Chandler, too. But I have to say this: Jim Lee hurt some football players. I know the effect he had on me. You had to know personalities. Freshman Archie Manning, Archie and Peyton Manning with John Underwood (2000)

Archie recalls his freshman year at Ole Miss. I was excited about going to Ole Miss, even if I didn't see myself as some cool guy about to make a splash at the biggest university in the state. ... Seven other freshman QBs came in with me in 1967, and that wasn't as unusual as it sounds. In those days, Division I schools could sign forty new players a year, and, with walk-ons, might very well field freshman teams of sixty or more players ... Some coaches with the biggest budgets were notorious for stockpiling, for signing players just to keep them from going to a rival school. But they couldn't keep forty players a year because that would mean 160-man rosters. Clearly, some weren't expected to last. Those from smaller schools were long shots. Drew ordinarily wouldn't send a scholarship player to a Division I university like Ole Miss more than once in ten years.

I had that in the back of my mind when I got ready to go to Oxford, along with the very real possibility that Coach Vaught would do what he had a reputation for doing: move some of us to other positions. ... But that summer I got a break that boosted my chances. I was selected for the Mississippi High School All-Star game, to play for the North team coached by Bob Tyler of undefeated Meridian High, and Tyler liked to throw the ball. His QB, Bob White, another Ole Miss signee, was a high school All-American and, of course, was all set to be Tyler's starter in the game. But Bob White had a bad knee, and early in the game he got hit hard and had to come out. I took his place - and immediately fumbled away the first snap. Fortunately, the North team's third QB wasn't a passer, so Coach Tyler left me in, and before the night was over, I had thrown for four touchdowns and ran for a fifth, and we won 56-33. When I was awarded the Most Valuable Player trophy afterward, I couldn't help thinking that I might not have played at all if Bob White had been healthy. ...

Archie Manning and Johnny Vaught On the first day, we eight QBs arrived to be counted, each of us sporting a shaved head from the freshman hazing process, and all of us scared to death. We waited for the jerseys to be passed out. And when they were, mine was red. I was first-string. Was I the best? I like to think so, but I'll never know and neither will they, because not only was I proud of that jersey, but I was possessive of it, too. I stayed number one throughout the freshman season. Would I have climbed up to first-team status if they'd given me the color jersey the eighth QB got ...? I like to think so, but we'll never know that, either. Staying "in the red" wasn't easy, though. Freshman players, by NCAA rule, were separated from the varsity then ... The freshman team had only a four-game schedule, so we practiced more than we played. But Ole Miss practices were long and tough, and making it tougher was that the freshmen played one-platoon then, meaning every player had to go both ways ... As a hedge against possible injury, QBs played safety on defense, the farthest point from the ball we could get and still be in the game, but there was a lot of hitting, a lot of tackling, a lot of hard work. I weighed 170 pounds at the start, but Coach Wobble ran us like mad, and whenever I gave them my weight numbers ... it was wishful thinking. I was below 160 most of the time. Besides that, freshmen didn't get the best-fitting equipment, and I dug a deep purple crease across the bridge of my nose from my helmet banging down every time I made a tackle. The crease lasted the season. I thought of it as a combat ribbon. ... I had my share of downers those first weeks. The kind freshmen can expect when they're suffering through learning pains and home-sickness at the same time. In our opening game we got beat 28-0 by LSU's freshmen, and at free safety I guessed wrong on a pass play that resulted in an LSU touchdown and got my ass chewed by Wobble Davidson. We had a break after that game and the freshman players were allowed to go home for the weekend. Some never came back. I had thoughts along those lines myself. In fact, on Sunday when it was time to drive back to Oxford, Buddy said, "You ready to go?" and I gave him one of those long pauses. But I had never quit anything I'd started, so what came out instead of "no" was "I guess so." I had no more doubts, and a lot more fun, after that. The next week I intercepted three passes against Alabama and we won, and then threw for four touchdowns when we beat Vanderbilt. Our last game was against Mississippi State. The night before, we met with the varsity and got our marching orders. Our hair was finally growing out, and one of the varsity players said, "I guess you know this game means more than all the others combined. If you don't win, we're gonna cut off your hair again." We won. Giving It All for the Game "Giving It All for the Game," Book of Football Stuff: Great Records, Weird Happenings, Odd Facts, Amazing Moments & Cool Things, Ron Martirano (2010)

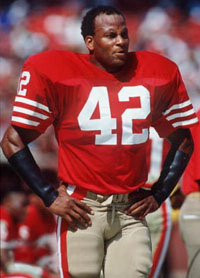

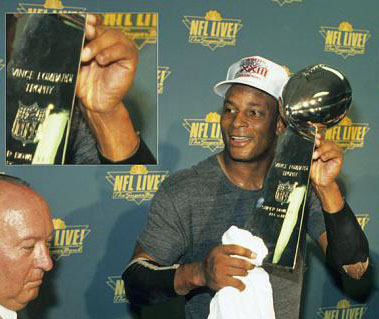

Ronnie Lott was one of the toughest defensive backs to play the game, and anyone who doubted it just needed to shake his hand. From 1981 to 1994, Lott owned the secondary, first as a cornerback and eventually as a safety. Over the course of his career, he was all-pro eight times at three different positions (cornerback, free safety, and strong safety). Statistically, Lott racked up five 100-plus tackle seasons with over 1,000 career tackles, and twice led the league in interceptions returned for touchdowns (beginning his rookie season with San Francisco where three of those TDs helped San Francisco get to the Super Bowl and almost won him the rookie of the year - Lott finished second to Lawrence Taylor). Lott started in twenty playoff games over the course of his career, with a shared record of nine postseason interceptions, en route to four championship rings. It's safe to say Lott gave more than 100%. He gave 110% ... and a pinky. The 49ers closed out the 1985 season with a pair of games against the Cowboys and the Giants. During the Dallas game, Lott was involved in a play that forever cemented his reputation as one of the toughest players in the game, and created a legend that took on a life of its own. While trying to take down Dallas FB Timmy Newsome, the hall of fame cornerback's finger got caught on his chest, leaving his hand in an awkward position when his body collided with Newsome's helmet. By Lott's account, "My chest acted like an anvil upon impact," and the results weren't pretty. When the play was over, his pinky was mangled. The story that emerged was that Lott went into the locker room and faced with having the pain of his broken digit impact his play, Lott made a seemingly impossible decision right on the spot. The truth is that Lott had his fingers wrapped in tape, and he played through the team's finale against the Giants before having the injury assessed during the offseason. The prognosis was that part of the bone was missing, left on the playing field, and the remaining pieces would never fuse back together. He was presented with two options. The first was an operation that would have required having a piece of bone removed from his wrist and grafted on to his finger, held in place with pins. It resquired possibly missing a few games the following season as well as being vulnerable to re-aggravating the injury. The second option: Cut off the tip of the broken pinky and play ball. One season and nine-and-a-half fingers later, Lott earned his third of ten Pro Bowl invitations.  Ronnie Lott holds the Super Bowl trophy with his amputated pinky showing The Prodigal QB Comes Home - I

The Game Plan: The Art of Building a Winning Football Team, Bill Polian (2014)

There are parts of Buffalo Bills history that are almost too bizarre to believe. And there's one part that I can say I'm particularly glad to have missed.

It happened in early June 1983, while I was working in the Canadian Football League. Two months earlier, the Bills had made Jim Kelly, the star QB from the University of Miami, the 14th-overall pick of the draft ... Jim was the third QB selected in the now-legendary Quarterback Class of '83, after John Elway ... and Todd Blackledge ..., Ken O'Brien ..., and Dan Marino ..., who amazingly was the next-to-last pick of the first round. Jim made it clear from the start he wanted nothing to do with playing in Buffalo. He went so far as to instruct his agents to get the best offers they could from the United States Football League's Chicago Blitz, which had drafted Jim, and the CFL's Montreal Concordes, who also expressed serious interest in signing him. Jim even made a visit to Chicago and, not surprisingly, came away very impressed with the Blitz's coach, the late, great Hall of Famer George Allen. Nevertheless, the Bills, with Pat McGroder serving as their interim GM ..., were undeterred. They kept negotiating with Jim's agents, Greg Lustig and A.J. Faigin, and finally put together a four-year, $2.1 million deal that Jim was going to sign. Or so it seemed.   Jim Kelly, Miami Hurricane and Houston Gambler As the story goes, Jim and his agents were in Pat's office, with Jim literally on the verge of putting pen to paper. All of a sudden, a phone call came in and a secretary, sitting outside the office, picked it up. It was from Bruce Allen, George's son and the general manager of the Blitz, asking to speak with A.J. Faigin. For whatever reason, she put the call through.

Allen was on a three-way connection that included the late John Bassett, principal owner of the USFL's Tampa Bay Bandits and one of the most influential voices of his league. About a month earlier, Bassett had invited Jim, his agents, and one of Jim's closest friends and former Hurricanes teammate, FB Mark Rush, to a Bandits game to give them a feel for the quality of play in the USFL. They spent several days at Bassett's plush condo in Sarasota, where they were treated like royalty. Allen and Bassett told Faigin to hold everything with the Bills, and that Faigin and Lustig should exit the building and meet them at Bassett's home in nearby Toronto to listen to an offer that would blow them away. They walked out, leaving behind a glaring blank spot on the contract where Jim was supposed to have signed his name. Later that night, Allen and Bassett informed them that the USFL was so determined to land Jim, he could have his pick of any of its teams. Allen said he would gladly trade Jim's rights to the team of his choice and he and Bassett promised that he would receive far more money than the Bills were offering. As a sweetener, they also extended the Pick-your-USFL-team proposal to Mark Rush, who had been a fourth-round pick of the Minnesota Vikings, and assured Jim that any USFL club would sign them as a package deal. The two of them put together their wish list of teams, and to no one's surprise, they were all warm-weather cities: Tampa Bay, Jacksonville, and Houston. Soon thereafter, Dr. Jerry Argovitz, the Houston Gamblers' owner and a dentist, invited Jim and Mark to Houston, where he would have the attractive opportunity to throw passes in the Astrodome. Before making a contract offer, Argovitz wanted to make sure Jim's shoulder, on which he had undergone surgery after severely separating it during his senior year of college, was fully recovered. Argovitz took Jim to a park and asked that he throw him some passes as he ran routes. Not quite sure of what to make of the owner of a professional football team running pass patterns for him, Jim, who had one of the strongest arms of any QB to play the game, figured he should take it easy to enhance Argovitz's chances of catching the ball. But Argovitz told him he wanted more velocity on the throws. "Okay," Jim said. "If that's what you want." The next pass wound up breaking the ring finger on Argovitz's right hand. Right after that, Argovitz, after receiving Jim's rights from the Blitz in exchange for four draft picks, signed him to a five-year contract worth $3.5 million, including a guaranteed signing bonus of $1 million. That made him the USFL's second-highest player after RB Herschel Walker. Jim would go on to have two brilliant seasons in Houston. Working in the runand-shoot scheme, he threw for 9,842 yards and 83 touchdowns. He completed 63 percent of his passes with an average of 8.53 yards per attempt. In 1984, Jim was MVP of the USFL, setting a league record for throwing for 5,219 yards and 44 touchdowns. ... You could not have lived in Buffalo during that time and been unaware of how the loss of Jim Kelly affected the perception of the franchise. It was viewed as just an absolute, outright stumble. And it felt doubly worse due to the earlier loss of a talented RB, Joe Cribbs, to the USFL because the Bills had allowed it to happen with incorrectly worded language in his contract. So they lost two players who arguably would have reached marquee status because they didn't have enough acumen to get the job done. That was just another example, in the public's mind, of the bumbling Bills. The Bills became fodder for Johnny Carson's late-night monologue. They were considered such an embarrassment, such a non-professional organization that, at one point, the late Larry Felser, a longtime sports columnist for the Buffalo News, wrote that the city just might be better off without them. That was a stinging commentary from Larry, who heavily influenced sports opinions in western New York. And the perception by players from other NFL teams and those coming out of the college ranks was: "These guys are minor-leaguers. This is an awful place to play, it's not a good place to work, it's not a good place to live." There was a malaise that surrounded the franchise that resulted from the losses of Jim Kelly and Joe Cribbs. Those weren't losses on the field. Those weren't because of injuries or poor coaching or anything that you could correct. They were because of poor business acumen, the inability to get the job done, or so people assumed. To be continued ...

The Prodigal QB Comes Home - II

The Game Plan: The Art of Building a Winning Football Team, Bill Polian (2014)

Part I Bill Polian became GM of the Buffalo Bills in 1984. In 1986, a potential trade materialized for Jim's negotiating rights, which we still owned. It would have involved some pretty high draft choices, and I thought it was something that Mr. Wilson [the Bills' owner] should at least consider. For one thing, it could have netted us, at the very minimum, a decent QB, along with allowing us to fill other positions. For another, Jim was going to be difficult for us to sign, because his price tag would be high for that time and he already had made it clear he had no desire to play for the Bills, so I thought we needed to look at a fall-back option.

"No!," Mr. Wilson said emphatically. "We're not going to do it. We're going to sign Jim Kelly." "Jim Kelly is going to cost a fortune to sign," I reminded him. "I know. We're going to sign Jim Kelly." ... In my mind, having actually seen him up close and personal for a whole season in the USFL, there was no question that he was going to be a great QB in the NFL. There were no questions about him physically, none about him mentally, none about him emotionally. He was so big, so strong, so tough, I honestly thought that we had a weapon that nobody else had. Guys like that are rare in professional football. ... They make everybody around them better ...   L-R: Bill Polian, Ralph Wilson, Marv Levy

On July 29, 1986, at the end of an 11-week trial in U.S. District Court in Manhattan, a jury awarded the USFL all of one dollar in its $1.7-billion antitrust suit against the NFL. That was trebled to three dollars. But the hollow nature of that "victory" was based on the fact the jury rejected all of the USFL's claims that the NFL's contracts with the television networks broadcasting its games constituted a monopoly, which was the very essence of its case.

Five days later, USFL commissioner Harry Usher announced that the league was suspending operations until 1987 (although it would never resume play), and a week later, the NFL announced that more than 600 USFL players were available to NFL teams. Soon thereafter, Al Davis, the late owner of the Raiders ... called me and said, "I'll give you any seven players on our team for the rights to Jim Kelly. Name the players." So I named Howie Long, an eventual Hall of Famer, and virtually every other star that they had. He said, "Well, I'll call you back." He never called back. Greg Lustig [Kelly's agent] then called me to say he wanted to meet. After receiving permission from the NFL office, I called Lustig back. The first thing he said was, "We don't want to go to Buffalo. We didn't want to go to Buffalo in the first place. We have no intention of going to Buffalo now." All Lustig wanted to talk about was convincing us to trade Jim's rights to the Raiders. I told him that he wasn't necessarily in a position to make that demand, but that I thought it was still appropriate that we get together. "Let me talk to Jim about what we have going here," I said. I had a week to prepare. My plan was to sell Jim on the Bills, making sure he understood we weren't as bad as our record or reputation said we were. ... We agreed to meet on August 14, 1986, in New York, at the Helmsley-Palace Hotel, which happened to be right across the street from Saint Patrick's Cathedral. I remembered being there as a little grade-school boy, touring that magnificent church. I considered that a good omen. I opened the meeting by sharing an anecdote of being with the Chicago Blitz while Marv Levy [the Bills coach] and I were on the sideline of a game against the Gamblers in the Astrodome. In the second half, our S, Doug Plank, was blitzing. ... Doug came after Jim and he popped him right under the chin. It was a hit that in today's NFL would get you ejected and suspended. You could see that he opened a gash in Jim's chin, yet, with blood pouring out, Jim stood back there and delivered a strike for a touchdown. Marv and I looked at each other and we both went, "Holy cow!" or words to that effect. I told Jim, "It was that play, more than any other, that convinced me that you're the kind of QB we need with the Buffalo Bills. ..." I also reminded him of when he beat us [the Chicago Blitz] in a Saint Patrick's Day blizzard in Chicago. I'm talking about 17-18 inches of snow. I said, "Heck, you played in a blizzard in Chicago. Why are you worried about a little snow in western New York?" We were just two guys talking football. ... I think it put Jim at ease a little bit, allowing me to gain some trust from him. After that, I went into my recruiting speech. I told him about Andre Reed, an extremely talented receiver ... I told him about Pete Metzelaars, who we had acquired in a trade with the Seattle Seahawks in '85. "We've got Bruce Smith on defense," I said. "We got some guys who can make plays on this team. This is not the mediocre outfit that it was when you were originally drafted in '83. It's a new, young team that you're going to grow with ..." "This whole thing has been built with you in mind. This is not an offense that we dreamed up out of whole cloth and we don't care who the QB is. This is an offense that requires a QB who can lead, who can make throws down the field, who can do the kind of things that are necessary to have a top-flight passing game. And we think that that's possible in Buffalo." At some point the idea of a trade to the Raiders came up and I said, "Well, Jim, here's the issue: we control your rights. They belong to us unilaterally, and there's no place that you can go of your own volition without our agreement. And I'm quite sure that we would never agree to trade you." "Well, what if I didn't come to Buffalo?" Jim Asked. "What if I just refused to play?" "Well, if that happened, I guess at some point in time we'd be inclined to maybe entertain a trade, because what skin is it off our nose if you don't play? We would be no worse off than we are now. But I can assure you that we wouldn't trade you to the Raiders, under no circumstances. It's not happening. Take it to the bank. It's just not happening." ... "This franchise has a cloud over it because we didn't sign you. Conversely, when we do sign you, that cloud will be lifted. ... The fans of Buffalo will welcome you with open arms. You're not just another football player coming to Buffalo. You're the prodigal son coming home to lead us to the Promised Land." ... On the morning of August 15, 1986, I was at the airport in Buffalo, ready to head to Houston, where I would meet with Jim Kelly's agents later that day. ... I got to the airport, and people there knew I was on my way to Houston to do the negotiations. There were actually children from a Catholic church in a northern suburb of Buffalo that brought along a little scroll, which was essentially a group of prayer thoughts for me. "We're praying for you when you go to sign Jim Kelly," a nun told me. ... I think the first day we went five to six hours and the discussion was focused on the Montana and Young contracts. I was trying to figure out what their "magic number" was. By the end of the day, I got to the point where I was pretty confident in saying to myself, I think a million a year is the magic number. By today's salary standards, that would be laughable for a backup QB, but it was unheard of for anybody in the NFL at the time. ... We called it a day. Our game against the Oilers was that night, and Jim attended as Ralph Wilson's guest in his suite at the Astrodome. ... I heard afterward that Mr. Wilson did a great job of selling Jim on the Bills and Buffalo. The next day, ... his agents were more receptive to what we were offering, which was a five-year deal worth $8 million, including a $1 million signing bonus. That made him, at least briefly, the highest-paid player in the NFL. Mount St. Haslett

From Tales from the Saints Sideline: A Collection of the Greatest Stories Ever Told, Jeff Duncan (2004)

The New Reality

Jenny Vrentas, Sports Illustrated, September 19, 2016 A few minutes after 8 a. m. LeSean McCoy walks into a windowless room on the first floor of the Bills' headquarters in Orchard Park, N.Y. He ... straps on a virtual-reality headset to stare down an NFL defense. In the 13-by-16-foot room, which is lined with FieldTurf, the eighth-year running back stands over a hash mark and peers through the goggles at a wall-mounted TV. His position coach, Anthony Lynn, cues up a running play from practice. "Oh, this is crazy!" McCoy says with a giggle. "Ha! Jim Brown would have loved to have this."

LeSean McCoy doing virtual reality practice "Rewind that," he says, breaking down a pass play. "Now, if that was an option route, oh, my goodness! You'd kill them on the inside move right there." McCoy takes another look, reciting the defensive front, the protection call, the coverage and how he should run his route. "We are running option routes," Lynn says of the Week 1 game plan for the Ravens, "and I have all these coverage looks on tape for you. Get you some mental visuals." "Nice!" McCoy says, adjusting the mask. "Can I get this at home, too?" This isn't Jim Brown's NFL, and it hasn't been for a long time. Virtual reality aside, today's game is an aerial spectacle; a league record for passing yards has been established each year since 2009. Backs are so devalued that only three were taken in the first round over the past four NFL drafts. (Ten were chosen over the previous four.) The new way of thinking: The guys who run the ball are interchangeable and replaceable - even the veterans. ... Buffalo was one of four teams that ran more than they threw last season (509:465), and its 152.0 yards per game and 4.8 yards per carry were league highs. Yet the job of a running back is misunderstood even in Buffalo's locker room. Defensive players occasionally mock the backs by asking, What, exactly, do you do in the film room anyway? Rookie Jonathan Williams, a fifth-round pick out of Arkansas, recently overheard one of the athletic trainers saying he wished he could be a running back, because it seemed so simple. "I told him, 'No!'" Williams says, still stunned. "We have to know a lot of stuff!" The Bills' game plan against the Ravens on Sunday contained nearly 50 running plays. Each came with an alignment (where the back lines up), designated footwork (there are at least a dozen varieties) and an aim point (what to run toward). As the back approaches the line of scrimmage, he makes his primary read off one defender. The best backs can almost simultaneously read a second defender - just like top QBs can read two safeties at once - and sense where daylight exists amid the chaos of violent collisions. Each play also has something called a "big alert," a presnap read that signals a favorable matchup for the back to seize. Something as simple as taking the wrong first step can muck up the timing of a carefully orchestrated play. ...

McCoy and Anthony Lynn The Bills had 10 protections in last week's game plan, each requiring adjustments at the line; the backs had to study about 30 base and nickel pressures of the Ravens' defense. By kickoff, Lynn had held 10 mini-meetings to go over theses protections alone, but the Ravens (two sacks, six QB hits) cooked up some new surprises. Whether the ball is on the ground or in the air, Lynn's primary goal is to find ways to slow down an impossibly fast game for his players. To help one of his younger backs, Mike Gillislee, Lynn asked third-string QB Cardale Jones to record audio of the Week 1 play calls so Gillislee could visualize responding (in seven-second increments, of course). Lynn also employs a method he calls "deep practice" - making the game harder during the week so it seems easier on Sundays. He has his guys do read-and-reaction drills from six yards deep instead of seven to give them less time to make a decisions. During a recent special-teams period Lynn put McCoy behind an "offensive line" of five garbage cans and rattled off Baltimore pressures at lightning speed, baiting McCoy into making mistakes as he made the protection calls. Paranoia Abounds

"Spying Eyes," Jon Solomon, Athlon Sports 2017 College Football Preview

Congratulations, Wakey Leaks. Wake Forest's game-plan breach from a highly unlikely source - radio analyst and former assistant coach Tommy Elrod - managed to make already-paranoid college football coaches even more paranoid. That is no small achievement. ...

Practices open to the media are now typically a distant memory. Television announcers who watch practice and receive inside access to the team are closely scrutinized by coaches. Covered fences prevent prying eyes from seeing anything at practice. During games, coaches even cover their mouths when talking to their players or into their headsets in case any alert lip-readers might be watching. ... In 2015, then-Georgia coach Mark Richt approached an AL.com reporter at practice during the week of the Georgia-Alabama game. The reporter was one of several journalists shooting video of receivers running routes with QBs near the end of a media-viewing period. "[Richt] asked what was being filmed and asked that tight shots of certain routes not be shown," AL.com wrote a couple of days before Alabama routed Georgia 38-10. "The coach said he didn't want Alabama seeing what they were doing at that moment. Richt then asked that all video recordings cease. The three viewing periods were open to photographers and videographers. Restrictions on what could be filmed were not listed on an advisory to media viewing practice." When Mike MacIntyre became Colorado's coach, he initially allowed the majority of his practices to be open to the team's fans. That lasted one season. "I got burned," MacIntyre said in 2015 about open practices ... "Last fall camp I did more, but I also got burned off that. I know for a fact, but I definitely want to do it."    L-R: Mark Richt, Mike MacIntyre, Gerry DiNardo Whether Orgeron will stay this open as LSU's permanent head coach remains to be seen. In an interview last fall, Orgeron said he wanted to be more open with the media. [LSU Coach Gerry] DiNardo had open practices everywhere he coached. During the week of an LSU-Georgia game, then-Bulldogs coach Jim Donnan called to tell DiNardo he needed to read some blogs. "They were telling everyone what we're doing at practice," DiNardo says. ... "I always stressed, 'Let's not share our ideas with the wrong people,'" DiNardo says. "When I was at LSU, Brad Scott was at South Carolina. We didn't play each other on the schedule. He asked to send his offensive staff to LSU during an off week. I said, 'Brad, I just can't do it.' You never know where your coaches will be in the future." Sometimes coaches even take advantage of visits with other staffs to help their own recruiting. In 2013, Clemson brought in a strong recruiting class but lost highly recruited defensive linemen Carl Lawson and Montravius Adams to Auburn at the very end. Clemson assistant coach Jeff Scott said Lawson and Adams told him that Auburn's superior housing for athletes was a major factor in their choices. So one day after meeting with Auburn coach Gus Malzahn's staff, Scott decided to see the Auburn apartments for himself. He snuck into one of them and asked a player if he could take some pictures. "He didn't know who I was, but I'm in there taking pictures of his room," Scott says. Scott showed the pictures to Clemson coach Dabo Swinney and university officials. Now the university is in the process of spending $2 million on renovations for an apartment complex that houses football players and non-athletes. ...    L-R: Brad Scott, Rick Neuheisel, Mike Riley At a meeting of the American Football Coaches Association, Neuheisel proposed more leniency for medical redshirt players. By limiting a medical redshirt to no more than three games, he wanted playres who got hurt early in the season to have the ability to return later to beef up rosters as injuries mount. Most teams just have a doctor fudge that the player was hurt the whole year anyway when in fact he can often return, Neuheisel says. "Every head coach looked at me like I was trying to pull a fast one on them," Neuheisel says. "It's the perfect scenario of the world of paranoia. They think because Rick Neuheisel has this reputation of being creative, the rule is a deal-breaker. I realized then the deal wasn't so much the rule I proposed, it was me. They didn't trust me. After that incident, Neuheisel took different approach with rules. One year at the Pac-12 coaches' meetings, Neuheisel wanted to increase the conference's travel-squad numbers (60 players per team) closer to the Big Ten and SEC limits (70 players). But Neuheisel knew he was toxic, especially in a room with so many big egos, such as Stanford's Jim Harbaugh and USC's Carroll. So Neuheisel had then-Oregon State coach Mike Riley pitch the idea. "Mike is the nicest guy in the world, so he pitched it to the ADs and we got 70," Neuheisel says. "Had Rick Neuheisel pitched it, we'd still be at 60. ..." |