Baseball

Vignettes – IV

Babe Ruth's 1927 Season – I

Babe Ruth's 1927 season was one of the most famous – if not the most famous – in baseball history. That was the year he hit 60 HRs to break his own record of 59 set in 1921. For 34 seasons, until Roger Maris broke the record with 61 in 1961, Babe's '27 season was remembered every time a slugger clouted round-trippers at a pace that might threaten the magic 60. So this is the first of a series of pieces about Ruth in 1927.

- Babe went to spring training in 1927 after ending the previous season in a unique way. With the Yankees trailing 3-2 in the bottom of the ninth of the seventh game of the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, Babe drew a walk off Grover Cleveland Alexander with two outs. He was then thrown out stealing at second with Bob Meusel (not Lou Gehrig, as is sometimes reported) at the plate.

- After making his second movie, "Speedy," in Hollywood in February, Babe signed the most lucrative contract in sports history to that point – three years at $70,000 per year.

- The 32-year-old superstar reported to St. Petersburg FL on March 7 weighing 223 and claiming to be in the best shape of his life.

- When the Yankees broke training camp to head north, their barnstorming opponents were the Cardinals. The matchup of defending league champions drew large crowds everywhere.

- 72,000 filled Yankee Stadium to watch the Yankees host the Philadelphia Athletics in the season opener April 12. Babe struck out in his first at-bat against Lefty Grove and was 0 for 3 when he left feeling dizzy in the sixth inning. Ruth bounced back to have a good series as the Yanks won three and tied one. He hit his first HR in the fourth game and threw out Al Simmons at home from deep RF.

- By the end of April, Babe had four HRs. The Yanks were 9-5 and tied for first. The lineup manager Miller Huggins used most of the season was as follows.

- Earle Combs CF

- Mark Koenig SS

- Babe Ruth RF

- Lou Gehrig 1B

- Bob Meusel LF

- Tony Lazzeri 2B

- Joe Dugan 3B

- Pat Collins/Johnny Grabowski/Benny Bengough C

- Waite Hoyt/Herb Pennock/Urban Shocker/Dutch Reuther P

Continued bellow ...

Reference: The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs, Bill Jenkinson

Top of Page |

Babe Ruth

Miller Huggins

|

Babe Ruth's 1927 Season – II

May was brutal for the Yankees.

- Thanks to the front office filling every open date with an exhibition game, the club had no scheduled days off until June 6.

- On May 6, on their way from Washington to Chicago, the Bronx Bombers faced a semipro team, the Lincoln Lifes, in Fort Wayne IN. With the score tied 3-3 in the bottom of the tenth and the big leaguers in danger of missing their train, Ruth announced to the crowd of 3,500 as he walked to the plate that he was about to end the game. Sure enough, he smashed the ball high over the RF fence.

- With Ruth smacking 12 May four-baggers, the Yanks ended the month two games in the lead over the surprising White Sox.

- His most prodigious clout came on the 23rd in Washington's Griffith Stadium into the CF bleachers which were 441' from home plate. He had done a similar feat in St. Louis 12 days earlier.

Griffith Stadium in a later era (Note lights)

- In the Memorial Day DH at Philadelphia's Shibe Park, Babe went 2-5 in the morning game. In the afternoon, A's manager Connie Mack, as he often did, walked Ruth intentionally in a crucial spot. While the four wide ones were being thrown, Babe offered to bat right-handed. In the eleventh, he hammered the ball into the upper deck in LCF to win 6-5. The next day, Ruth had four hits and two HRs as the Yankees swept the second of the back-to-back DHs, 10-3 and 18-5. In the seventh inning of the nightcap, Ruth took one swing right-handed, then slammed a double left-handed.

Continued below ...

|

Babe Ruth's 1927 Season – III

After hitting five HRs in the last four days of May, Babe Ruth entered June with 16 round-trippers. He hit another on the 5th and one on the 7th for 18.

- During pregame batting practice at Yankee Stadium on June 11, Ruth stepped out of the box, saying that he "felt a homer coming on" and didn't want to save it for the game. After walking in the first inning, he clouted one almost to the scoreboard behind the RCF bleachers. In the fifth, he hit one even harder, on top of the tall RF bleachers and almost out of the park. As Babe rounded the bases, Cleveland C Luke Sewell inspected the bat and found that it was much heavier than his own. "Black Betsy," as Ruth called it, weighed 44 ounces, the heaviest in the league at that time. Babe earlier in his life had used bats weighing as much as 54 ounces.

- In a DH at Fenway Park on June 22, Ruth clouted a pair of four-baggers, his 23rd and 24th. The first hit a building across the street beyond the CF fence. The second bounced into a garage across the street in RF. The next day, Lou Gehrig hit three HRs.

- To show the dangers posed by the incessant exhibition games the team was forced to play, the Yankees stopped in Springfield MA. Babe whacked two HRs and a right-handed double. However, he also wrenched his right knee, which caused him to miss four straight "real" games.

- When Babe returned to action on June 29, he showed no ill effects of his injury, going 4-for-5. His only out was scorching liner to the 1B. On the last day of June, he hits his 24th HR.

- A record crowd of 72,641 gathered on the 4th of July at Yankee Stadium for a DH with the Senators. Babe didn't disappoint the throng with five hits, although none were homers. He did smash a triple over the head of CF Tris Speaker (in his only season with Washington) that bounced against the wall beyond the flagpole, a distance of about 475'.

- Playing LF in Detroit, Babe argued for five minutes that a fan had interfered with his attempt to make a play. In his next at-bat, the crowd booed loudly until he belted a pitch to the top of the bleachers in RCF for his third HR in two days. Those same fans now cheered him. The Yanks went 13-5 on their four-city Western swing to take a 13-game lead.

- Back at Yankee Stadium on July 26, Ruth hit two HRs in a DH against the St. Louis Browns as part of a 7-for-9 day. His contributions were not limited to hitting. On the 30th, he threw a "perfect strike" to nail runner at home from deep RF.

- Since the pennant race was effectively over, attention turned to the race between Ruth and Gehrig for the HR crown. Entering August, Babe had 34 HRs but Larrupin' Lou, who, of course, had not missed any games, had 35.

To be continued ...

Reference: The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs, Bill Jenkinson |

Babe Ruth

Lou Gehrig

Top of Page |

Babe Ruth's 1927 Season – IV

Comiskey Park

Lefty Grove

Tom Zachary

|

Babe Ruth entered August with 34 HRs, one behind his teammate Lou Gehrig.

- August 5 at Yankee Stadium, Babe hit "the longest two-bagger ever" in the words of the New York World reporter. The ball bounced into the wall in dead center on one hop, 480' away.

- On August 15, Babe treated the exhibition game crowd in Indianapolis to a "breathtaking" HR that sailed high over the RF wall and landed half a block away. Just to prove he could do it almost any time he wanted, Ruth clouted one either further at Comiskey Park in Chicago the next day. That season was the first in which the park had a double-deck grandstand in the OF. The architect had predicted that no one would reach the roof, 75' high. The dimensions were 365' down each line. But facing Tommy Thomas in the fifth, the Bambino smashed a fly that easily soared over the grandstand roof. It landed in the parking lot off the left edge in the aerial view at the right. To add to the herculean accomplishment, the ball was poleaxed against the wind!

- Four days later, at League Park in Cleveland, Ruth blasted another HR almost as far. He finished August with nine HRs to lead Gehrig 43-41.

- September 2 in Philadelphia, Ruth lined one over the CF fence, but Lou walloped two to pull to within one in the HR derby. The next day, a significant game took play. Babe had two singles and a 425' flyout to CF, but Lefty Grove shut out New York 1-0 – the only whitewash of the Bronx Bombers that season.

- In the Labor Day DH in Boston, Gehrig hit his 44th. In the second straight twinbill the next day, Lou took the lead temporarily in the fifth inning. Falling behind energized the Babe who, an inning later, clouted one into the left-to-right breeze over the CF wall. It was estimated to have traveled 500'. Before the two games were completed, Babe smacked two more round-trippers, then whacked another the next day in the series finale.

Gehrig would hit only two more four-baggers to end with 47. Hitting behind Ruth, Larrupin' Lou totaled 175 RBI. Meanwhile, Babe took aim at his record of 59 HRs set in 1921.

- On September 8, the Yankees returned home, where they would play the remainder of their schedule. Babe's 50th came on September 11 off Milt Gaston of the Browns. Many men in the crowd reacted by throwing their straw hats on the field. Afterwards, Ruth said he had a chance to break his record if hurlers would give him some decent pitches.

- Probably because the Yankees were running away with the pennant (they would finish 18.5 in front), Babe got his wish. He walked only nine times the rest of the way. He hit seven more HRs in the next 14 games.

- With three games to play, Ruth needed two to tie and three to break his six-year-old record. On September 29, as the Yanks belted the Senators 15-3, the Bambino went 3-for-5 with 2 HRs. The other safety was a triple off the RCF fence. The next day, Tom Zachary served up #60, part of Ruth's 3-for-3 day.

- In an approach that no manager today would follow, Miller Huggins continued to start his usual lineup all the way to the last day. But Ruth went 0-for-3. That made his final regular season statistics these, where yellow numbers are league leaders:

BA .356, HR 60, RBI 164, Slg% .777, R 158, W 137

|

Christy Mathewson

|

Christy Mathewson with the Philadelphia Athletics? A first baseman instead of one of the greatest pitchers of all time? Both of those possibilities nearly came to pass, as we'll see in this series of articles tracing how Matty ended up playing for John McGraw, a coupling that propelled both to the Hall of Fame.

We pick up the story in 1900 when 19-year-old Christopher Mathewson joined the New York Giants of the National League, which at that point was the only "major league."

- Matty was fresh out of Bucknell College, where he was accustomed to success on the gridiron, the basketball court, and the diamond. In fact, he was best known as a FB and said he enjoyed football best of all. The one and only Walter Camp acclaimed him "the greatest drop-kicker in intercollegiate competition."

- An outstanding student, Christy played in the band, sang in the glee club, acted in the dramatic society, wrote poetry, and served as class historian as well as class president.

1901 Bucknell Baseball Team: Christy is seated second from right |

Andrew Freedman

John McGraw

|

While still in college, Matty pitched professionally during the summers, which was not against the rules in that era before the formation of the NCAA.

- It was during such a stint in the New England League that he learned to throw what became his signature pitch, the "fadeaway" or, as it would be called later, the "screwball."

- Still, when Matty joined the Giants in mid-July 1900, he didn't consider this "freak pitch," as he called it, a part of his repertoire. Fearing injury to his arm from turning his wrist the opposite way from the motion for a curve ball, he utilized the fadeaway only a few times in a game.

- It wasn't long, though, before he started throwing it more often as he realized he couldn't make it on just his curve and fastball.

Matty's debut with the Giants in the "pitcher's box" (as the mound was called in 1900) was anything but spectacular.

- Christy had pitched superbly for Norfolk in the Virginia League, going 20-2 in just half a season. The club owner had offers from New York, Cincinnati, and Philadelphia. So he gave his young star a choice. Matty chose the Giants because the team sat in last place in the NL, thus increasing his chances of playing immediately. Giants' owner Andrew Freedman agreed to pay $1,500 for the 6'2" right hander.

- The "debutante" (as rookies were called) entered in relief on July 17 against the Brooklyn Superbas at their home field, Washington Park. The defending NL champs touched him for five runs in his first full inning. In three innings plus, he hit three batters, uncorked a wild pitch, and surrendered four hits as the Giants lost 13-7.

- His next appearance proved to be even more of a disaster - six runs in his first inning of relief in Pittsburgh.

- On August 4, Matty came in early against the St. Louis Cardinals at Robison Field. He again had trouble with his control, giving up five walks and striking out only one. He rapped his first ML hit, a triple, driving in a run and scoring another in the 9-8 loss.

- One of the Cardinals Matty faced was their 3B, John McGraw, who had two hits, at least one of which came off the rookie.

- Manager George Davis used Christy three more times before Freedman sent the 0-3 hurler back to Norfolk to avoid paying the purchase price.

- The experience made Matty doubt his ability to pitch in the major leagues. He returned to Bucknell and considered a career in forestry or the Presbyterian ministry.

|

Ban Johnson

Connie Mack

Top of Page

|

However, events conspired to keep him in baseball.

- Ban Johnson, president of the Western League, organized the American League for the 1901 season. The new circuit considered any player who had not signed a contract for the new season to be fair game.

- Connie Mack, owner-manager of the new Philadelphia Athletics franchise, was familiar with Matty because of his Bucknell exploits. So Mack offered Matty a $1,200 contract. Christy replied that he would not report until the school term ended in June but would play the remainder of the season for $700. So on January 19, Mathewson signed the contract in the presence of witnesses. In mid-March, in debt and needing book money, Christy asked for a $50 advance, which Connie sent.

When Freedman learned that Matty had signed with the A's, he fired off a letter to the P demanding to see him. Mathewson recalled the meeting in a 1914 article in Sporting Life.

As soon as he saw me, he shut the office door, pulled up his chair, shook his finger at me and said, "See here, young man, what is this I hear about you and the American League? Don't you know that you belong to my club, and that you will either play in New York or you won't play at all?"

I was completely taken aback and said, "Why, Mr. Freedman, I am already signed up with Connie Mack."

"That don't make any difference," said Freedman, "the American League won't last three months, and then where will you be? Every player who goes with that league will be blacklisted. He won't be able to play anywhere else as long as he lives, and furthermore, you are the property of this club, and if you refuse to live up to your agreement, I will bring suit against you myself."

This was a remarkable revelation to me ... and taking full advantage of my childish ignorance, he so wrought on my imagination that I didn't know where I was at. I naturally didn't want to forego my future career as a ball player ... and I didn't want to go with a league that wouldn't last three months. But at the same time I didn't want to go back on my word to Connie Mack, so I explained to Mr. Freedman that I had already received $50 in advance money and asked him if he would return this money to Mack. He said he would and we left the matter in that way. I immediately wrote to Connie Mack, explained the situation, told him I was threatened with a suit by Mr. Freedman, and asked him if he would stand behind me in this suit. To this communication I received no reply. ...

In any case, ... the beginning of the season found me pitching for Andrew Freedman. Incidentally, he persistently forgot to return the $50 to Connie, so when I had received enough salary to enable me to do so, I refunded the money myself.

- Freedman was apparently bluffing because he had not completed the transaction with Norfolk and therefore did not own Mathewson's services.

- But Mack expected Matty to live up to the contract he had signed with the A's and report to Columbia Park on April 1. Instead, the P reported to the Giants on that date.

- An April 4 report in a Philadelphia paper stated:

Matty ... yesterday tried to escape the legal responsibility for his acts by sending a check for $50 to the manager of the local club. But manager Mack, upon the advice of his lawyers, refused to accept the same, returning it uncashed with a letter ordering him to report here at once. If Matty refuses he will likely be made the defendant in two suits, one for breach of contract and the other for receiving money under false pretense.

- Mack ended up taking no action against Matty.

Continued below ...

|

References: The Old Ball Game: How John McGraw, Christy Mathewson, and the New York Giants Created Modern Baseball, Frank Deford (2005)

Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball, Norman Lee Macht (2007)

|

22-year-old Christy Mathewson pitched for the New York Giants in 1901 after his dalliance with the Philadelphia Athletics.

- Matty put the shellackings of his rookie season behind him as he beat the Brooklyn Superbas 5-3 in the home opener before a "huge turnout of ninety-eight hundred."

- He proceeded to win his next seven outings and on July 15 twirled a no-hitter at St. Louis. Newspaper articles didn't use the term "no-hitter" yet. For example, the New York World printed:

He pitched a remarkable game, not only disposing of the Cardinals without a hit but shutting them out without the semblance of a base hit as well.

- Owner Freedman was so pleased with Matty's pitching that he gave him two suits in mid-season as a bonus.

- Unfortunately, the team wasn't doing well, finishing 7th in the eight-team National League.

- Christy led the staff with 20 victories (of the club's 52) against 17 defeats with a 2.41 ERA, by far the best on the team. He completed 26 of his 28 starts and threw five shutouts.

In the off-season, Giants manager George Davis jumped to the Chicago White Stockings in the fledgling American League.

- To replace him, Freedman hired a former Philadelphia sportswriter named Horace Fogel who, needless to say, didn't gain the respect of the players, especially the veterans.

- The season hadn't progressed far when one newspaper called the Giants "positively the rankest apology for a first-class ballclub that was ever imposed upon any major city."

- In a time when a great deal of anti-Catholic feeling existed in the U.S.A., the team split along Protestant-Catholic lines, which meant the Irishmen against everyone else.

- Matty, a Presbyterian, tried to keep out of line of fire and earn the "substantial raise" of $3,500 Freedman gave him, which aroused the jealousy of his teammates, including the real leader of the team, Heine Smith.

- When Freedman fired Fogel in June, Smith took over and listened to his regulars who demanded the removal of Mathewson from the starting rotation.

- So Matty played 1B only to have the fielders purposely make bad throws. Newspaper accounts began referring to the future Hall of Famer as "Christy Mathewson, the former pitcher."

Meanwhile, further south on the East Coast, John McGraw was also suffering through his season with the Baltimore Orioles.

Continued below ...

|

Christy Mathewson 1902

George Davis

Heine Smith

|

References: The Old Ball Game: How John McGraw, Christy Mathewson, and the New York Giants Created Modern Baseball, Frank Deford (2005)

Top of Page

|

John McGraw 1902

Ban Johnson

Tommy Connolly

John Brush

|

After being dealt by the Baltimore franchise of the National League to St. Louis for the 1900 season, 28-year-old John McGraw returned to the Orioles in 1901 as player/manager in the brand new American League.

- McGraw led the team to a 68-65 record, good for fifth place. But John hated playing and managing in the new league because he couldn't stand AL president Bancroft "Ban" Johnson.

- The American League had grown out of the Western League, which had been headed by Johnson since 1894. In that post, Ban set out to make baseball a more family-friendly game. He insisted his umpires crack down on rowdy play so that families could attend games without hearing bad language and witnessing violent behavior.

- Johnson insisted on respect for umpires whereas McGraw was the premier umpire-baiter of his day. So Johnson ordered his arbiters to take nothing from Mugsy.

- McGraw complained that the umps treated him and his team unfairly. For example, all a player had to do was complain that 3B McGraw had held him by the belt as he rounded third, and the ump would grant the run even though he hadn't seen the offense.

McGraw didn't last the 1902 season.

- In late May, McGraw was spiked in a game against Detroit, suffering a three-inch gash below his knee. In a rage, Mugsy smashed the jaw of the Tiger who injured him.

- Johnson suspended McGraw for five days.

The next incident that hastened McGraw's departure from the junior circuit occurred June 28 in game against Boston at Baltimore.

- Presiding at the game was Mugsy's least favorite umpire, Tommy Connolly.

- A complicated play occurred with the Orioles at bat in the eighth. A chopped ball with runners on second and third led to a botched rundown between third and home, with the runner on second moving to third before returning to second and the batter reaching second before returning to first.

- With Orioles safely on every base, the Red Sox appealed that the runner on second had "cut the bag" (failed to retouch third) when he ran back to his original base. Connolly agreed and ruled the runner out.

- McGraw, of course, couldn't restrain himself and engaged in a heated argument with Tommy that caused the arbiter to order the manager from the field. When Mugsy refused to leave, Connolly forfeited the game to Boston.

- The home fans were enraged. As the Boston Globe reported:

Then it was gravely suggested that the umpires be hung, the police rushed into the breach, the peace was preserved and over 3000 people trolleyed home.

- Mugsy was livid over his treatment by Connolly.

I used no expletives. Nor did I do anything that would warrant my being sent to the clubhouse, yet Connolly, in a most insulting way, ordered me off the field. I made up my mind right there that I would no longer stand for being made a dog and refused to go.

- Two days later, Johnson suspended the recalcitrant manager again, this time indefinitely. McGraw used the time off to travel to New York and begin secret negotiations with Giants owner Andrew Freedman about taking over his team.

- McGraw exacerbated the situation by expressing scathing opinions publicly. He labeled the American League "a loser," called Ban Johnson "a czar," and disparaged Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics "white elephants" - a tag that the A's proudly turned into a mascot.

- Undoubtedly baiting Johnson into kicking him out of the league, McGraw said further:

I would be a fool to stay here and have a dog made of myself by a man who makes no pretense of investigation or givig a hearing to both sides.

- Johnson's response? The muttering of an insignificant and vindictive wasp.

- That was the last straw as far as McGraw was concerned. Having loaned the Orioles franchise $7,000 of his own money, he demanded that the club either reimburse him or release him. Since the owners didn't have $7,000, they released Mugsy.

- On July 8, McGraw was introduced as the new manager of the Giants, although he had secretly signed a contract several days earlier. Mugsy then made a public promise to his former fans in Baltimore.

I wish to assure Baltimore that in consideration of their kindness, I shall not tamper with any of the Baltimore Club's players. I would not do that, because of my friendship for the people here, and because it would not be right.

- But, as was often the case with McGraw, he was being ingenuous at best and outright dishonest at worse. Conspiring with Freedman and Reds owner John Brush, McGraw swung the sale of the Orioles franchise to them. They promptly released six of their higher-priced players, including C Roger Bresnahan and P Joe McGinnity, who immediately signed with the Giants along with two of the other former Orioles.

- Seeing through the sham, Johnson, in concert with Baltimore's minority owners, took control of the franchise after only one day, a day when the Orioles had to forfeit their game because they didn't have enough players.

- The whole episode would culminate after the season with Freedman selling the Giants to Brush and Johnson engineering the move of the Baltimore franchise to New York, where they would compete as the Highlanders against the NL's Giants and Dodgers.

In the meantime, Johnson was glad to be rid of Mugsy.

McGraw was one of the hardest men in the league to control and now that he has left I cannot see how the American League has lost anything.

One of the first moves McGraw made as Giants skipper was to return Christy Mathewson to the mound. Within two years, Mugsy would lead the last place club to the NL pennant, giving himself and Brush an opportunity to retaliate big time against Johnson.

Continued below ...

|

References: The Old Ball Game: How John McGraw, Christy Mathewson, and the New York Giants Created Modern Baseball, Frank Deford (2005); The Biographical Encyclopedia of Baseball (2000)

Baseball Vignettes Archive | Top of Page

|

When John "Mugsy" McGraw signed an $11,000 contract to manage the New York Giants in July of 1902, he made wholesale changes.

- He cut nine of the 23 players, which angered the owner who had just hired him, Andrew Freedman, who would have to eat $14,000 in salaries. Still, the boss could do nothing since he had given his new skipper complete control of the team.

- Calling Christy Mathewson's exile to 1B by the previous manager "sheer insanity," McGraw restored Mattie in the pitching rotation, thus quelling rumors that the hurler was "not on the best of terms" with the new manager and would be dealt to St. Louis.

After lackluster attendance at best, the fans turned out to see what the new regime produced.

- 16,000 nearly filled the park for the first home game back in the Polo Grounds on July 19 after the western swing.

- McGraw started a P he had brought with him from the Orioles, Joe McGinnity, and inserted himself at SS. Even though the Giants lost 4-3, the fans appreciated the team's new spirit.

- Mathewson made his first start at Brooklyn on July 24, shutting out the Superbas 2-0 on five hits.

- In no time at all, the sportswriters for the multiple daily newspapers in New York City went from lambasting the woeful Giants to singing Mugsy's praises.

McGraw, however, had written off the season.

- He spent a great deal of time on the road, scouting prospects and players on other clubs he could trade for.

- Mathewson ended up leading the staff with 14 wins against 17 defeats. Eight of his victories were shutouts, and his final ERA was 2.11.

- Matty also benefitted from watching McGinnity pitch. In particular, Christy developed a much better change-up.

- The Giants stayed in last place the rest of the year, but the stage had been set for a remarkable improvement in '03.

Freedman sold the club at the end of the season.

- John Brush sold his controlling interest in the Cincinnati Reds and brought the Giants.

- The new owner was a difficult man to deal with, in part because he suffered from rehumatism and a disease of the nervous system (possibly caused by syphilis). However, McGraw loved him, in large measure because they shared a detestation of American League president Ban Johnson.

Intent on spoiling Brush and McGraw's plan for ascendency in the Big Apple, Johnson shifted the Orioles franchise from Baltimore to New York.

- Unknown to anybody at the time, of course, Johnson's move finalized the establishment of the 16 franchises that would stay in their locations in the National and American Leagues until 1953 when the St. Louis Browns filled the major league void in Baltimore.

- The new owners of the AL New York franchise were William Devery, former police commissioner known for corruption, and Frank Farrell, known as "the poolroom czar," hardly the most savory of characters for a league that Johnson boasted was much more family-oriented than the NL. Their club would now be called the Highlanders.

- McGraw, however, paid no mind to what was going on in the rival league that he considered inferior to his own.

- Mathewson's big event in the off-season was marriage to Jane Stoughton despite the trepidation of her father about having a son-in-law who would "make a living playing a child's sport with a bunch of uneducated ruffians." Christy and Jane had met at Bucknell University.

McGraw led the Giants all the way up to second place in 1903.

- McGinnity and Mathewson both won 30 games, with Joe one ahead of Christy with 31. "Iron Man" Joe won both ends of doubleheaders three times. (McGinnity actually earned his nickname a few years earlier from working in an iron foundry in Oklahoma.)

- Matty led the league in strikeouts with 267. In the opinion of Frank Deford, Mathewson became "the first real full-blooded American sports idol."

- Only two of the eight regulars returned from 1902: 1B Dan McGann and 3B Billy Lauder. One of the new players was Roger Bresnahan, a future Hall of Fame C who patrolled the OF his first few years with McGraw.

- The National League kings, the Pittsburgh Pirates, who finished 6.5 games ahead of New York, squared off against the Boston Pilgrims, champions of the upstart AL, in the first World Series.

- Since the two leagues had signed a peace agreement before the season aimed primarily at stopping the bidding wars for players, the Pirates met the Pilgrims in the first "World's Championship Series." McGraw and Brush were not pleased that Pirates' owner Barney Dreyfuss had personally agreed to the series with Boston owner Henry Killilea and then even more irritated when the Pilgrims won, five games to three.

Mugsy got revenge against Johnson the following season.

- With Art Devlin replacing Billy Lauder at 3B and Bill Dahlen at short insteda of Charlie Babb, the Giants won the 1904 NL pennant by 13 games over the Chicago Cubs. McGraw's boys increased their wins from 84 in '03 to an amazing 106.

- The M Boys, McGinnity and Mathewson, improved to 68 combined victories, 35 for Joe and 33 for Christy. In addition, Dummy Taylor, a deaf-mute, contributed 21 W's.

- Boston repeated in Johnson's circuit, edging the Highlanders by a game and a half.

- However, McGraw had made known earlier that he had no intention of playing the AL pennant winner.

Why should we play this upstart club or any other American league team, for any post-season championship? When we clinch the National League pennant, we'll be champions of the only real major league.

- Mugsy's words should have surprised no one since as early as July, Brush had stated publicly that his club would not play the AL winner.

- The Giants argued that the rules for the post-season series were haphazardly defined, being whatever the two competing clubs agreed upon for number of games, how proceeds would be distributed, and so on. Since there was no authoritative body that had made participation compulsory, they were free to decline. All this reasoning, of course, was meant to obscure the real reason for the Giants' refusal - hatred of Ban Johnson.

Criticism from his own fans as well as writers from all around baseball stung Brush into adopting a different stance.

- In January, 1905, Brush drew up rules for the post-season series. Included was the 4-of-7 format.

- The NL agreed to make World Series participation mandatory for its champion.

- As a result, when the Giants again copped the NL pennant, they met Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics in the second "World's Series."

|

Joe McGinity

Dan McGann

Billy Lauder

Roger Bresnahan

Art Devlin

Bill Dahlen

Top of Page |

References: The Old Ball Game: How John McGraw, Christy Mathewson,

and the New York Giants Created Modern Baseball, Frank Deford (2005)

|

Branch Rickey, Brooklyn Dodgers GM, told his manager, Leo Durocher, by Leo's own admission in his autobiography, that "I was a man with an infinite capacity for immediately making a bad thing worse. Carve it on my gravestone, Branch. I have to admit it's sometimes true."

- During 1945, the last World War II season, "when the Dodgers were playing anybody who could fit our uniforms," one of the pitchers on Durocher's staff was 34-year-old Tom Seats, a left-hander with many mediocre years in the minors and a stint with Detroit in 1940.

- He had earned a spot with the Dodgers because the year before he had won 25 games with San Diego in the Pacific Coast League. He pitched only on the weekends because he was working in an airplane factory, which exempted him from the draft.

- With Brooklyn, however, Tom couldn't make it past the third inning. Durocher: "He was strong as a bull; he had a good curve; his control wasn't that bad. And he kept getting his jock knocked off."

- Finally, coach Charlie Dressen had an idea. "You know, Leo, they tell me this guy drinks. Can you get any whiskey around here?" Leo scraped up two dozen of the little half-pint bottles of brandy.

- Before Seats' next start, Leo called him into his office. When the southpaw admitted he had no clue as to why he wasn't doing better, the manager pulled out one of the little bottles of brandy and poured him a shot.

- Let Leo relate what happened.

He took one gulp, and I could see that the next time I wouldn't have to worry about the glass. He warmed up, and I want to tell you something; by the time the game was ready to start the brandy was pouring out of him. That sonfagun pitched five scoreless innings. They couldn't touch him. And then I took him into the clubhouse, let him get into a dry uniform and gave him another big belt.

From there on in he was the best pitcher we had. [Sears finished the season 10-7.]

At the end of the year, Rickey called Leo to his office to congratulate him on the fine job he had done with Seats. Branch asked what Leo's secret was.

- Knowing that Rickey as a fundamentalist Christian didn't drink, Leo nevertheless told him that he gave Sears a shot of brandy before he warmed up and another shot in the fifth inning. Durocher:

Rickey's eyebrows always seemed to become twice as thick when he was angry. He just kept staring at me, and then his eyes began to squint, and I knew I was in trouble. "You ... gave ... a ... man ... in ... uniform ... whiskey?"

I didn't think he'd appreciate the distinction between whiskey and brandy, and so all I said was, "'Yes, sir."

He said: "'He will never pitch again for Brooklyn." His eyes got even smaller. "I should fire you right now."

- Durocher defended himself, saying that Rickey had hired him to win as many games as possible. "I saw nothing unethical about what I did. I just gave a man a little drink of brandy. I think it gave him more confidence, loosened him up. It must have done something, Mr. Rickey, or he couldn't have had what you just called such a transformation. Now what it was, Mr. Rickey, I don't know. But it certainly got the job done."

- Rickey stuck to his pledge that Seats would never pitch for Brooklyn again. In fact, he never appeared in another game for any ML team.

Durocher concluded, "I never came closer to losing my job."

Reference: Nice Guys Finish Last, Leo Durocher with Ed Linn (1975)

|

Branch Rickey

Leo Durocher

Tom Seats

Top

of Page |

Juan

Mad Dude

Shag

Crawford, a National League umpire

for two decades, died July 11, 2007. He was the home plate umpire for

two of the most memorable plays in baseball history. We'll talk about

the first one here and catch the other in the next Vignette.

August

22, 1965: Candlestick Park, Los Angeles

vs San Francisco

It was the fourth game of a series in which the

bitter West Coast rivals battled for the NL lead. The first three games

had been fraught with knockdown pitches and threats. The visitors had

taken two of three as the teams traded half game leads. A Sunday crowd

of 42,807 watched the teams' aces, Juan

Marichal for SF

and Sandy

Koufax for LA,

duel in the finale. Marichal decked Ron Fairly

and Maury Wills in the first few innings. Crawford

warned both dugouts, meaning that any further brushbacks would result

in ejection of the pitcher and manager. Dodger

C John Roseboro told Koufax on the

bench that he (Roseboro) would "take care of it."

When

Marichal

batted in the third inning, Roseboro let a 1-2

pitch drop at his feet and then fired the ball back to the mound

just inches from Marichal's ear. Without saying

a word, Juan turned around to confront Roseboro,

who stood up and took off his mask. Feeling threatened, Marichal

banged the catcher on the head with his bat, opening a 2-inch

gash in Roseboro's skull. With blood gushing

down the catcher's face, the two teams brawled for 14 minutes.

When

order was restored, Marichal was ejected. A shaken

Koufax walked the next two batters and gave up

a three run HR to Willie Mays. "The only

time I ever beat him with one," Mays said.

The Giants won 4-3

to regain first place.

Players,

coaches, and managers could not recall ever seeing an attack with

a bat. Marichal was suspended for nine games

and fined $1,750. The two turns he missed hurt the Giants

because they lost the pennant to the Dodgers

by two games. Koufax finished 26-8 with a 2.04

ERA. Marichal didn't have a bad year either:

22-13, 2.14 ERA. LA

won the World Series in seven games over the Twins.

|

|

Roseboro

later sued Marichal for $110,000 in damages. After

the suit was settled out of court, the two men somehow became friends.

In fact, Roseboro was one of the first people Juan

called when he was elected to the Hall of Fame.

|

|

Another

Met Miracle

Shag

Crawford, a National League

umpire for two decades, died July 11, 2007. He was the home plate

umpire for two of the most memorable plays in baseball history. One

is discussed above (Marichal attacks Roseboro with a bat). This Vignette discusses the other event.

Game

4, 1969 World Series, Baltimore Orioles

vs New York Mets, Shea

Stadium

Shag ejected Baltimore

manager Earl Weaver in third inning for arguing balls

and strikes, the first time a manager thrown out of World Series game

since Cubs manager Charlie

Grimm in 1935. So Weaver was not around

to protest a tumultuous 10th-inning play. Score tied 1-1, Mets

with runners on first and second and none out. J.C. Martin,

pinch-hitting for Tom

Seaver (the starter who had pitched all 10 innings),

bunted. The throw to first by P Pete Richerts hit

Martin on the left arm and bounced into right field.

This allowed Rod Gaspar to score the winning run

from second.

A

photo

later showed Martin running in fair territory. Since

he wasn't inside the three-foot-wide runner's lane in foul territory,

he should have been ruled out and the runners sent back to their original

bases. Neither Crawford, umpiring at home, nor first

base ump Lou DiMuro called Martin

out for interference. Orioles

coach Billy Hunter, running the team in Weaver’s

absence, didn't argue. Crawford said afterward that

Martin was either touching or straddling the foul

line and therefore running legally, even though his body was essentially

in fair territory. The Mets

went on to win the Series in five games.

Shag

Crawford's son Jerry has been a MLB umpire

since 1977. Another son, Joey, has refereed in the

NBA since 1977.

|

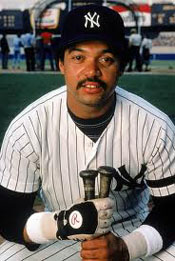

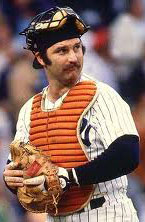

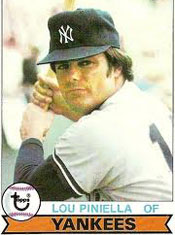

Reggie Was Hip That Night

Reggie Jackson

Thurman Munsen

|

The

1978 World Series had one of the most controversial plays in Fall Classic

history. Reggie

Jackson's five HRs (including three in one game) had powered

the Yankees to the championship

over the Dodgers the previous year. He now played a

major role in Game 4 in '78 with his bat, as you would expect, but also

with his hip.

October

14, 1978 - Yankee Stadium – Yankees

trail the Dodgers 2-1 in games.

- Bottom of sixth –

Los Angeles starter Tommy John is

cruising with a 3-0 lead.

- However, New York scores a run on a one-out Jackson

single that plates Roy White and moves Thurman

Munsen to second.

Lou

Piniella steps to the plate.

- The future Cubs

manager hits a sinking liner to the left of Dodger SS Bill

Russell. The ball hits Russell's glove and

falls to ground.

- Munson takes off for third, but Russell

steps on second to force Jackson and throws to first

to try to complete an inning-ending double play.

- Meanwhile, Jackson,

expecting Russell to catch the liner, returns to first.

As the throw comes in, Reggie, with his back to second,

turns his right hip to the ball. It hits him and bounces into RF, allowing

Munson to score the Yankees'

second run.

Dodger

manager Tommy

LaSorda is livid.

- He argues that "Mr. October"

interfered with the throw and could not impede the play made on another

runner. Piniella should be called out at first.

- Frank

Pulli, the NL ump at first base, disagrees, saying Jackson's

interference was not intentional.

- So Munson's run stands.

- Dodger

1B Steve Garvey, the closest person to the play, later

says Reggie's play was "quick thinking, but dirty

pool."

New York ties the game

in the 8th on a Munson double and wins in the tenth

on a Piniella single. The Yankees also win the next two games to defend their crown.

After

the Series, Lasorda said, "I think the Reggie

Jackson play changed the complexion of the whole Series because

Tommy John was winning that ballgame. It would have

been the third out." (Reference: Baseball Digest, August

2007)

|

|

|

|

The

Pine Tar Game

July

24, 1983, Yankee Stadium: In the top of the

9th, the Yankees lead the Kansas City Royals

4-3 with two out and a man on. George Brett swats a

HR into the right field bleachers off Yankee closer

Goose Gossage to give KC an apparent

5-4 lead. Yankee manager Billy Martin,

on the advice of coach Don Zimmer, asks the umpires

to check Brett's bat. By measuring the bat against

the width of home plate, they discover that the pine tar extends past

the 18-inch limit stipulated by the rules. Home plate umpire Tim

McClelland calls Brett out, giving the Yankees

a 4-3 victory. Brett charges out of the dugout and

has to be restrained from bumping McClelland. One commentator

stated: "Brett has become the first player in

history to hit a game-losing home run."

The

Royals protest the game to American League president

Lee MacPhail, who upholds the protest, saying the umps

should have removed the bat without penalizing the player. He orders

the game to be completed from the point of Brett's

homer. Predictably, Yankee owner George Steinbrenner

is incensed: "It sure tests our faith in our leadership. If the

Yankees lose the division by one game, I wouldn't want

to be Lee MacPhail living in New York. Maybe he should

go house hunting in Kansas City."

The

final 1 1/3 innings are completed on August 18 (an off day for both

teams) with the Royals holding on to their 5-4 lead.

With only 1,200 fans in the stands, Martin mocks MacPhail's

ruling. He puts pitcher Ron Guidry in CF and left-handed

first-baseman Don Mattingly at second base. Before

the first pitch to Hal McRae (who followed Brett

in the order), Martin challenges Brett's

HR on the grounds that Brett had not touched all the

bases, claiming there is no way the umpires (not the same crew as the

original game) can dispute this. But umpire Davey Phillips

produces an affidavit signed by the July 24 crew certifying that Brett

had touched all the bases. Martin continues to argue

until he's ejected from the game (which was probably his objective all

along). Yankee reliever George Frazier

strikes out McRae to end the 25-day-long top of the

ninth. Dan Quisenberry then sets New York

down 1-2-3 in the bottom of the inning.

Brett

continued to use the controversial bat until he broke it in a game.

He loaned it to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1987. As it turned out,

the Pine Tar Game didn't affect the pennant races. NY

finished third in the AL East, seven games behind the Orioles.

The Royals finished second in the West, 20 games behind

Tony LaRussa's surprising White Sox.

Martin

later admitted that he had known for two weeks that Brett's

bat was illegal but bided his time before protesting. Furthermore, there

was a precedent in his favor. On July 19, 1975, Yankee

C Thurman Munson hit a homer against the Twins,

who protested to umpire Art Frantz that Munson

had pine tar too far up the handle. Frantz nullified

the HR and called Munson out. A month later, Martin

protested the Angels' bats for having too much pine

tar. Umpire George Maloney denied his protest, saying

he couldn't tell whether the substance was dirt or tar. Martin

then waited eight years to try his pine tar ploy again.

Reference:

Baseball Digest, August 2007 | Top of Page |

|

CONTENTS

Babe Ruth's 1927 Season - I

Babe Ruth's 1927 Season - II

Babe Ruth's 1927 Season - III

Babe Ruth's 1927 Season - IV

Mugsy and Mattie - I

Mugsy and Mattie - II

Mugsy and Mattie - III

Mugsy and Mattie - IV

From Bad to Worse

Juan Mad Dude

Another Met Miracle

Reggie Was Hip That Night

The Pine Tar Game

Baseball Vignettes Index

Baseball Page

|