|

|

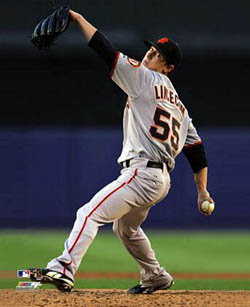

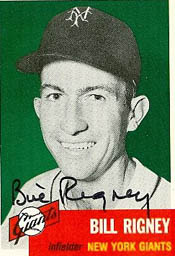

Tim Lincecum

|

His teammates nicknamed him "The Freak" and "Seabiscuit" because of the power he generates from his 5'11" 170 lb body. But Tim Lincecum was programmed to be a power pitcher from a very early age.

- Tim's father, Chris, pitched in semipro ball until injuries curtailed his career. He began a lifelong study of the biomechanics of pitching.

- Chris began applying the fruits of his study with Tim's older brother. Some of Tim's earliest memories are of watching his dad teach his brother, who is 3 1/2 years older, how to pitch. "I was this little four-year-old kid watching my brother and learning the same mechancis. You can see me on film when I was a little kid. It's a smaller body, but the same mechanics."

- Under his father's tutelage, Tim developed a motion that maximized the power he could generate when throwing the ball without putting too much strain on his arm and shoulder. Chris videotaped every one of Tim's high school appearances and analyzed them with him much as a football coach tutors his QB.

- As a 4'11" freshman, Tim's velocity was only 70 mph. He reached the mid-70s by his sophomore year, 80-82 his junior year, and finally, as a senior, hit 86 on the gun.

- The Cubs selected Tim in the 48th round of the 2003 draft. However, Lincecum opted to accept a scholarship at the University of Washington.

- At Washington, Tim earned PAC-10 Pitcher of the Year and first-team All-American honors as well as breaking the conference record for strikeouts. His college career culminated with the 2006 Golden Spikes Award as the top collegiate player in the country.

- In the '06 draft, the Giants selected Tim with the 10th pick despite continuing concern on the part of some ML scouts because of his size. Among the nine teams who passed on Lincecum was Seattle, whose scouting director was axed after the '08 season when Tim was the NL Cy Young Award winner. The Mariners' first round pick in '06, P Brandon Morrow, has struggled to establish his role, alternating between starting and the bullpen.

- In addition to winning the Cy Young, Lincecum led the majors in 2008 in Ks (265) and strikeouts per 9 IP (10.5). He also topped the NL in winning percentage (.783), was second in ERA (2.62), and third in IP with 227.

- In 2009, Lincecum led the majors in strikeouts at the All-Star break, during which he started for the NL in the summer classic in St. Louis.

|

Reference: "Big League Spotlight: Tim Lincecum," Reds Magazine, July-August 2009 |

After smashing Ty Cobb's "unbreakable" record of 96 steals by eight in 1962, Maury Wills became a marked man in the National League.

- In 1963, Wills stole only 40 bases in 59 attempts.

- The next season he set a NL record by winning the SB title for the fifth time in a row. However, he stole just 53 sacks while getting caught 20 times.

Maury felt his reduced number of thefts was not just the result of teams concentrating on keeping him off base and training pitchers to hold him on better and catchers to release the ball quicker. The 1962 NL MVP believed that umps were not enforcing the balk rules. He vented his frustration to the press after a 1964 game.

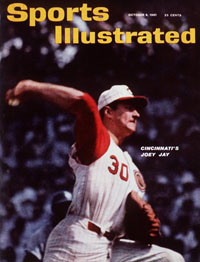

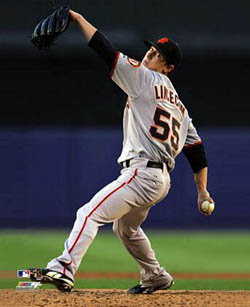

Joey Jay was pitching for Cincinnati one day last August and he seemed just a bit ruffled. For he was working against the Los Angeles Dodgers in Dodger Stadium and in the very first inning Maury Wills reached first base and got Dodger fans buzzing. Buzzing because where there's a Wills, there's a way he'll get around the bases – by stealing. ... He jiggled around and drew two throws from the cautious Jay.

The crowd tensed for Maury's dash to second, and Wills was leaning that way, too, as Jay went into his motion to pitch. But Joey shot the ball to the first-baseman and Maury Wills was picked off. And tagged out. Wills protested. Jay, he charged, had balked twice. Maury told the umpire that Jay had given him a fake knee-bend once, had come to a full stop the next time, and then had quick pitched his next delivery. The umpire dismissed Wills, and Maury went to the dugout shaking his head.

In the clubhouse after the game, the Dodger SS couldn't contain himself.

- He accused NL president Warren Giles of forcing his umpires to refrain from calling balks. Wills said further that one ump was deprived of his Christmas bonus the year before ('63) and another had his salary cut because they enforced the balk rule, which called for the P to come to a discernible stop in his motion before delivering the ball.

- Giles responded by suggesting that Wills "get his facts straight before making public statements." Giles said the league did not pay Christmas bonuses to umpires and had not reduced any arbiter's pay.

- Wills countered that he had had a long talk with an umpire. "He told me the whole story. Last year the umpires who were calling all those balks early in the season were called in the NL office. At first the league office had wanted the balk rule enforced. Then the umpires really started calling a lot of them and they were told to cut down." Since the stop requirement was being ignored, it was much harder to read the pitcher and get the jump needed to steal. In fact, he said, "it's easier now to steal on left handers, when just the opposite was true several years ago."

This was not the first time Maury had a confrontation with the NL president. During his record-breaking '62 season, the San Francisco Giants wet down their infield before a game with the Dodgers to slow down Maury. He angrily protested to the umpires and was thrown out of the game. Giles fined him $50. When LA went from SF to Cincinnati, where the league headquarters was located, Wills personally delivered his fine in pennies – 5,000 of them.

1965 saw Wills extend his league-leading SB streak to six in a row and return to his '62 form with 94 thefts. He was caught 31 times. (He had been caught only 13 times in his record-setting year.)

|

Maury Wills

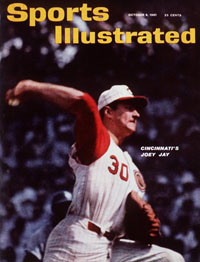

Joey Jay

Warren Giles

|

Reference: "Maury Wills: Thief with a Gripe," Al Goldfarb, Complete Sports, September 1965 |

|

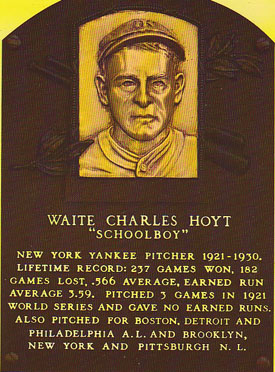

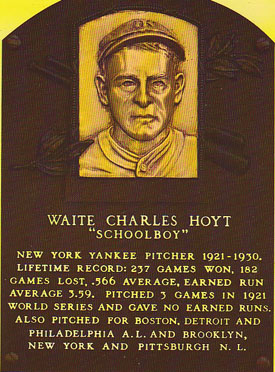

Waite Hoyt

Ed Barrow

Waite Hoyt with his future broadcasting partner, Joe Nuxhall

|

Waite Hoyt was signed to a contract by the New York Giants when he was a mere 15 years old. To sweeten the pot, the Giants gave him a $5 bonus! His father took the money immediately, considering it too much for a boy to carry around in 1915.

Hoyt pitched one scoreless inning for the Giants in 1918, striking out two. The next season he was in a Boston Red Sox uniform.

- Waite appeared in 13 games for the Bosox in 1919, compiling a 4-6 record.

- In 1920, he went 6-6 in 22 games as a starter/reliever. Then came the break of his life.

On December 15, 1920, Hoyt was traded to the New York Yankees as part of a four-for-four swap. Ed Barrow, the GM who had gotten him for Boston, now ran the Yankees and knew Waite's potential. The trade reunited him with Babe Ruth, who had been traded by the Red Sox the year before.

- Hoyt provided the Yanks with solid starting pitching for nine seasons during which he won 155 games.

- In 1927, he won a league-high 22 for the Bronx Bombers.

- He won six World Series games in the six Fall Classics in which he participated in a Yankee uniform.

- His best Series was his first, 1921. He pitched three complete games without giving up an earned run. Unfortunately, one of the two unearned runs he surrendered cost him a 1-0 decision to Art Nehf of the Giants, who was his opponent in all three contests.

- During the 1920s, Hoyt coined the phrase "It's great to be young and a Yankee."

Hoyt started what would become his second career a few weeks before the 1927 World Series. Since the Yankees clinched the pennant by Labor Day, NBC hired him for a 15-minute baseball program each Monday night for the last four weeks of the season. Waite was encouraged by the positive reviews he received from the NY press.

After winning 23 in 1928, Hoyt signed a contract that paid him $20,000. However, he slumped to 10-9 in 1929. On Memorial Day of 1930, he was sold to the Detroit Tigers. During the 1931 season, the Philadelphia Athletics claimed Hoyt on waivers, and he helped Connie Mack's club reach the World Series, his seventh. He started the fifth game, a 5-1 loss to the St. Louis Cardinals.

By now a journeyman hurler, he finished his career with seven seasons in the National League. In 1934, he showed flashes of the old Waite, winning 15 for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Even before his retirement, Waite kept his hand in radio. During the winter of 1937, he appeared on the "Grandstand and Bandstand" show on WMCA. The next year, he had his own 15-minute sports program on WNEW. He also did post-game shows for the Brooklyn Dodgers, his last team as a player. Discouraged in his hopes to do play-by-play in New York City, Hoyt jumped at the offer from WKRC in Cincinnati. A pioneer in baseball broadcasting when Larry MacPhail was GM, the Cincinnati Reds contracted with three stations to air their contests simultaneously.

One of the first things Waite had to do as a play-by-play man was to learn how to keep score, which he never had to do as a player. He worked hard to polish his style to compete with the more experienced broadcasters on the other two stations. Eventually, though, his knowledge of the game as a former player and matter-of-fact style made him the favorite of the fans, who particularly enjoyed his rain-delay stories about Babe Ruth and the other greats he played with and against. He lasted 24 years in the Reds booth.

In 1952, Waite pioneered the simulcast — broadcasting on both radio and TV at the same time. On the other hand, he was the last of the ML announcers to abandon the studio recreations of road games using telegraph reports. He finally had the pleasure of calling the World Series when Cincinnati played the Yankees in 1961. The fans honored him with "Waite Hoyt Day" at Crosley Field September 5, 1965, his final season in the booth. The climax of his long career in baseball came when he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1969. Waite died in 1984.

|

|

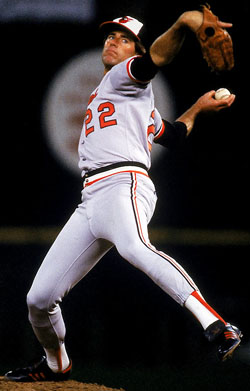

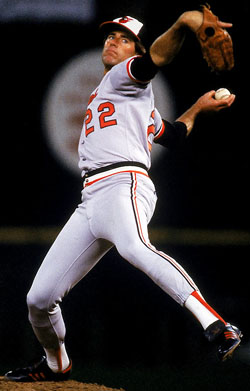

The One and Only Earl Weaver

Hall of Famer Earl Weaver wasn't a conventional manager - at least if believing in the hit-and-run and the bunt makes you conventional. He also didn't believe in removing his starters because of a pitch count.

Earl Weaver confronting the umps

- Weaver won one pennant by making only 167 pitching changes in 159 games. Another year he used only 12 pitchers for an entire championship season.

- He enunciated his famous mantra "Pitching, defense and the three-run homer" after a 1979 game in which his pinch-hitter hit a walkoff 3-run HR in the tenth.

- "Before Moneyball, before Beane, before Bill James .... Weaver, a white-haired gnome who never played a day of MLB, knew what worked." Red Sox GM Theo Epstein: "He would develop arms on the big league level by bringing up a young P and putting him in the bullpen, mostly out of long relief. Once he got some experience he could move into the rotation."

- After managing in the minors, Earl was hired by the Orioles midway through the 1968 season. He immediately asked the PR director to compile stats on how each Oriole batter did against opposing Ps and vice-versa. Before each series, the stat crew would give Weaver the batter-pitcher matchups handwritten on sheets of paper. (No PCs in those days. Earl probably wouldn't have used one anyway.) On many occasions, Weaver went against conventional wisdom because the stats told him that, for example, weak-hitting SS Mark Belanger could hit Nolan Ryan. So in a tie game in the 10th with runners on second and third, Earl let Belanger face Ryan, and Mark drove in both with a single.

Jim Palmer

|

- Bill James wrote: "He used everybody. Probably more than any other manager in history, Weaver had carefully defined roles for every player on his roster - not because he cared about the players, but because he cared about the games." Earl was not a "players' manager." He spoke to his charges only when necessary. His feud with star P Jim Palmer is legendary. "Weaver liked winning a whole lot more than he liked ballplayers. He never shook his winning P's hand after a game. He wanted nothing to do with emotion or friendship." Palmer's explanation: "I don't think Earl ever wanted anything to do with anything that interfered with him winning baseball games."

- Weaver is best remembered for his clashes with umpires. He was thrown out of more games than any AL manager in history. He was thrown out in spring training. He was tossed twice in the World Series and twice in one day. (YouTube video of Earl at his best/worst - not for sensitive ears.)

- Weaver was no fan of team speed (except on defense). Once, when asked a question by the host on his radio show about why the Orioles didn't have more team speed, he replied: "Team speed, for crissakes! You get *** little fleas on the *** bases getting picked off, trying to steal, getting thrown out, taking runs away from you. Get some big ***s who can hit the *** ball out of the ballpark and you can't make any *** mistakes." (The diatribe didn't actually air but was taped as a joke. Hear it on YouTube - foul language galore!)

- "I never had a hit-and-run. No sign. ... I hear it on the radio. Get a guy on first. He walked. The pitcher is 2 and 0 on the next batter. 'Perfect time for a hit-and-run,' the announcer says. If the P could throw a strike, don't you think he would have thrown it to the guy on first?"

- Earl managed Baltimore for 12 full seasons (1969-1980) during which the team failed to win 90 games only twice (and won 88 in one of those years).

- fter he retired from the Os, Weaver turned down George Steinbrenner who asked him to manage the Yankees in 1985. That would have been quite an act! Weaver and Steinbrenner would have outzanied Billy Martin-Steinbrenner.

|

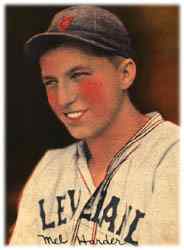

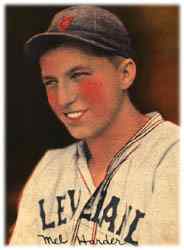

Mel Harder

|

Unsung Star of '34 All-Star Game

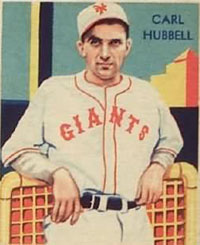

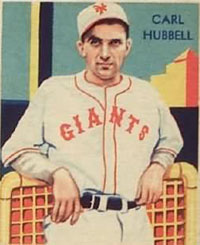

Carl Hubbell of the New York Giants is famous for striking out five batters in a row in the 1934 All-Star Game at his home park, the Polo Grounds.

- 2B Charlie Gehringer of the Detroit Tigers led off the game with a single to CF. Then Hubbell walked LF Heinie Manush of the Washington Senators. With Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmy Foxx coming up, the AL was licking its chops at the prospect of jumping out to a good lead.

- Instead, Hubbell dashed the AL's hopes by freezing Ruth with a screwball on the outside corner for strike three. Gehrig struck out swinging as the runners stole second and third. Then Foxx went down swinging as well.

- 2B Frankie Frisch of the Cardinals led off the bottom of the first with a homer to give the NL a 1-0 lead.

- "King Karl" began the top of the second by striking out CF Al Simmons of the White Sox and SS Joe Cronin of the Senators. After C Bill Dickey singled, Hubbell struck out P Lefty Gomez.

- Hubbell not only fanned five future Hall of Famers but his victims were, in order, the men who ranked first, second, third, and fourth on the AL's career HR list at that time.

- Karl completed his three-inning stint with a scoreless third with no more Ks.

Later in the game, another hurler, this one for the AL, pitched splendidly although his feat is rarely remembered.

- The NL scored three in the bottom of the third off Gomez before the AL cut the lead in half with two in the fourth. Then a six-run fifth propelled the Junior Circuit to a 8-4 lead.

- However, the Senior League responded with two in the bottom of the fifth and had runners on first and second with none out against Red Ruffing. AL player-manager Cronin brought in Mel Harder of the Indians. [An oddity of the game is that both teams had player-managers as Bill Terry of the Giants skippered the NL.]

- Harder retired the side, although a double-steal produced another run to pull the NL within one, 8-7.

The AL scored an insurance run in the 7th, but Harder didn't need it.

- Mel hurled four more innings of shutout ball to make the AL 2-for-2 in the new Midsummer Classic. Harder's pitching line showed five IP with only one H, one W, and two Ks.

- The official scorer declared the Cleveland ace the winning pitcher. Yet Mel doesn't receive his due for his feat of five scoreless innings against the NL's best. For example, here's a comment from baseball-almanac.com about the game.

The hero of the game? Earl Averill who pinch-hit in the fourth inning and knocked a triple scoring two runs. In the fifth inning, he responded again with two additional runs batted in on a hard hit double.

Reference: All-Star Game 2009, Official Program

|

|

C Bill Bergen has been called "without question, the worst hitter in the history of baseball."

- William Aloysius Bergen played from 1901-1911 with the Cincinnati Reds and Brooklyn Superbas. In those eleven years, he compiled a lifetime average of .170 in 3,028 AB. No one has ever played so long and hit so poorly in the major leagues.

- Bergen's banner year at the plate was 1903 when he hit .227 for Cincinnati. In no other season did he hit over .190.

- In 1909, Bergen hit .139, the lowest average ever for a player who qualified for the batting title. During that season, he went 46 at-bats in a row without a hit, the longest streak ever for a non-pitcher.

- What kept Bergen in the majors? As you might have guessed, he was considered a skillful defensive C. Sporting Life magazine (6/12/1911) summarized the plight of the team that owned Bergen.

There has been an idea in Brooklyn for some years that Bergen is the greatest catcher in the National League. That's the exaggeration of hero worship. He is one of the best fielding catchers in the National League, but to be the greatest catcher in the National League he must necessarily be more than a great fielder. The idea that simply because a man is a fine fielding catcher he is the greatest catcher in the business is obsolete. Time was when managers thought that if they had a catcher who was mechanically perfect in fielding and throwing, they had the first essential toward a championship. By and by some of them woke up to the contrary.

- Brooklyn "woke up to the contrary" and released Bergen after the 1911 season. He played three more seasons in the minors. He hit all of .265 for Newark-Baltimore of the International League in 1912 before dropping below the Mendoza line the last years.

|

Bill Bergen (1903)

|

|

Babe Ruth taking batting practice at Wrigley Field before Game 3 of the 1932 World Series Babe Ruth taking batting practice at Wrigley Field before Game 3 of the 1932 World Series

Charlie Root

Gabby Harnett

Bill Dickey

|

The "biggest fairy tale in baseball history" (to quote the late Jerome Holtzman, who was named baseball's Official Historian in 1999) allegedly took place at Wrigley Field in the third game of the World Series between the New York Yankees and the Chicago Cubs on Saturday, October 1, 1932.

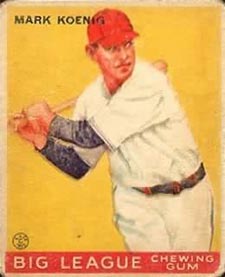

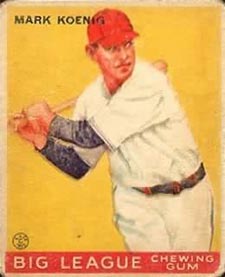

- The Series featured one of the worst cases of bad blood between the two combatants of any Fall Classic. It started at the end of the regular season when the Cubs voted Mark Koenig, a former Yankee, only a half share of World Series money. Koenig had been called up from the minors on August 17 to replace regular SS Billy Jurges, who had been shot by his fiancee. In 33 games, Koenig hit .353, exactly 100 points higher than Jurges, and sparked the Chicago stretch run.

- The Yankees considered the vote unfair to their old teammate and, led by Babe Ruth, derided the Cubs as "cheapskates." As a consequence, there was more bench jockeying and shouting of insults at the other club than usual during the first two games.

- After New York took the first two games at Yankee Stadium, they faced a hostile, overflow crowd of 49,986 in Chicago for Game 3. As Ruth warmed up in RF, fans threw lemons at him and castigated him continuously.

- Babe retaliated by swatting a three-run HR deep into the RCF bleachers in the first inning off starter Charlie Root. The next time up, he flew out to RF KiKi Cuyler up against the bleachers.

By the time the Bambino stepped into the box with one out and none on in the fifth, the Cubs had tied the game at 4. What happened next is the most famous at-bat in history.

- As Babe approached the plate, "a concerted shout of derision broke out in the stands, a bellowing of boos, hisses and jeers. ... From the Cub dugout came a series of abuses leveled at the Babe." (Richard Vidmer in the New York Herald Tribune the next day)

- Vidmer again: "Root whistled a strike over the plate. Joyous outcries filled the air and the Babe held up one finger as though to say, 'That's only one. Just wait.'"

- After two balls, Root quick-pitched Babe for strike two. "The Chicago players hurled their laughter at the great man but Ruth held up two fingers and still grinned, the super-showman."

- "On the next pitch, the Babe swung. There was a resounding report like the explosion of a gun. Straight for the fence the ball soared on a line, clearing the farthest corner of the barrier, 436 feet from home plate. Before Ruth left the plate and started his swing around the bases, he paused to laugh at the Chicago players ..."

- Vivid imagery by Vidmer but nary a word about Ruth pointing to the bleachers to indicate where he would hit the next pitch. In fact, of the 100 or so writers who covered the game, only one, Joe Williams of the New York World Telegram, said that Ruth had pointed to CF. And Williams later recanted.

The myth of Ruth predicting his HR seems to have originated in articles by Bill Corum and Tom Meany three days after the game.

- Corum for the New York World Journal: "Words fail me. When he stood up there at the bat before 50,000 persons, calling the balls and strikes with gestures for the benefit of the Cubs in their dugout, and then with two strikes on him, pointed out where he was going to hit the next one and hit it there, I gave up. That fellow is not human."

- Meany on the same day in the New York World Telegram: "Babe's interviewer interrupted to point the hole in which Babe put himself Saturday when he pointed out the spot he intended hitting his HR and asked the Great Man if he realized how ridiculous he would have appeared if he had struck out? 'I never thought of it,' said the Great Man. He simply had made up his mind to hit a HR and he did."

What about Babe himself? What did he say?

- He is not quoted after the game as claiming he called his shot. In fact, when asked the following spring if he had pointed to the bleachers before he connected, he said: "Hell, no! ... Only a damned fool would have done a thing like that. If I'd have done that, Root would have stuck the ball right in my ear."

- Unfortunately, "Ruth fell in love with the story" because "it was another jewel in his crown." He started fueling the fable. In hundreds of subsequent interviews, including tapes made for the Hall of Fame, he insisted he had pointed.

What about the other players?

- C Gabby Hartnett, who had a front row seat for the drama: "If he had pointed at the bleachers, I would be the first to say so. He didn't say a word when he crossed the plate."

- Cub 3B Woody English: "He didn't point. He was looking directly into our dugout. He never pointed to center. If he had done that, Root would have knocked him down."

- Root, of course, was repeatedly asked about the incident. "If I thought he was trying to show me up, I would have knocked him on his tail. It's strange. I'm better known for that – for what never happened – than for the things that did happen."

- Koenig, Ruth's pal from the '27 Yankees: "As far as pointing to center, no, he didn't. You know darn well a guy with two strikes isn't going to say he's going to hit a HR on the next pitch."

Did Ruth's teammates confirm the story?

- LF Ben Chapman: "He was pointing at the pitcher. Someone asked him, 'Babe, did you call that HR?' Babe answered, 'No, but I called Root everything I could think of.'"

- C Bill Dickey: "Ruth got mad at that quick pitch [for the second strike]. He was pointing at Root, not at the CF stands. He called him a couple of names and said, 'Don't do that to me anymore.'"

When asked, "How do you know?" Dickey replied, "Because Ruth told us when he came back to the bench."

"How come you never told anybody?"

"All of us players could see it was a helluva story. So we just made an agreement not to bother straightening out the facts."

|

Reference: Baseball, Chicago Style: A Tale of Two Teams, One City, Jerome Holtzman and George Vass

|

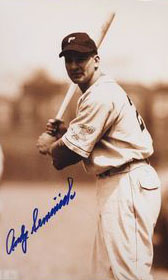

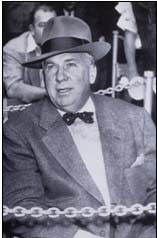

The league-leading Philadelphia Phillies hosted the fifth-place New York Giants before 14,955 at Shibe Park on August 12, 1950. According to manager Eddie Sawyer, a key player in the Phils' success was 30-year-old C Andy Seminick, one of the veterans of the "Whiz Kids." "From an indifferent, ordinary C, Andy has become a real take-charge guy and has made our young pitching staff." CF Richie Ashburn later recalled Seminick as "an easygoing guy" but "a tough Russian. You never wanted to get him riled up."

Andy showed his take-charge nature that Saturday afternoon against Leo Durocher's Giants.

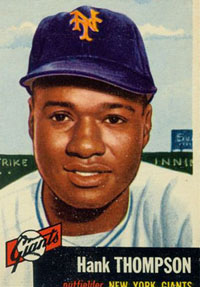

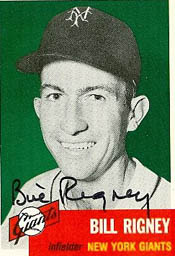

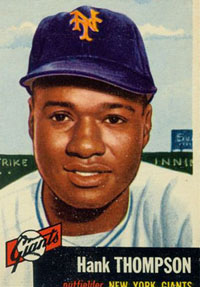

- In the second inning, Seminick reached 1B safely. Then, on a base hit, Andy "bumped hard" into 3B Hank Thompson, knocking him out, as Seminick scored on the errant throw. Bill Rigney replaced Thompson.

- In the fourth, 2B Eddie Stanky began waving his arms while Seminick was batting. The Brat had done this against the Phils and Boston Braves previously, but, before the game, Stanky had announced that he would drop the tactic until a ruling was made by NL President Ford Frick. However, when Stanky refused to stop the distraction, he was ejected. The Giants played the game under protest, claiming there was nothing in the rules prohibiting what Stanky did. Rigney moved to 2B while Lucky Lohrke took over at third.

- When play resumed, Seminick reached first on 1B Tookie Gilbert's error. The next batter, Mike Goliat, bounced to SS Alvin Dark who tossed to Rigney to force Seminick. Andy slid hard with spikes high into Rigney, and the two swapped punches. Players from both teams rushed out, and it took the four umps and four policemen to restore

order. The police threatened to arrest Gilbert for "using profane language"

until Umpire Lee Ballanfant talked them out of it. The combatants who began the fracas were sent to the showers. Both would be fined $25 by the league.

- The final game of the series went off without confrontations. However, Thompson did not return to the lineup.

The Giants got revenge against Seminick the last week of the season.

- On September 27, the Phillies played the Giants a DH at the Polo Grounds. Sawyer's crew had seen its lead, which had been 7 1/2 games on September 20, dwindle to 5 over the Brooklyn Dodgers.

- The first game was tied 7-7 in the bottom of the 10th with the Phils' ace reliever Jim Konstanty on the hill. Monte Irvin was at second when Dark hit a single up the middle. Irvin slid hard into Seminick at the plate to beat the throw and win the game.

- Seminick was injured on the play. The original report called it a sprained ankle, and the Giants team doctor opined that the injury wasn't serious.

- Andy sat out the second game, another loss that reduced the lead to 4.

It turned out that Seminick's injury was serious – a broken ankle.

- The Phillies had to play another DH against the Giants the next day.

- After taking shots to dull the pain, Seminick caught both games.

- New York won each game 3-1 to reduce the Phils' lead to 3 games as the Dodgers split with the Braves.

Andy also caught the last two games of the season against the Dodgers as the Phils held on to win the pennant by one game. He then took his spot behind the plate in all four games of the Yankees' sweep of the World Series. Seminick then spent eight weeks in a cast.

|

Andy Seminick

Eddie Stanky

Top of Page

|

|

|

Babe Ruth taking batting practice at Wrigley Field before Game 3 of the 1932 World Series

Babe Ruth taking batting practice at Wrigley Field before Game 3 of the 1932 World Series