Baseball Short Stories - 12

Too Close for Comfort

Dom Amore, Baseball Digest (July/August 2020)

James H. Clarkin journeyed to Boston on September 9, 1918, with the best of intentions - and a fantastic idea. The nation was at war ..., and everyone wanted to make the boys "Over There" feel as much at home as possible.

The folks in Hartford CO wanted to raise money, buy as much sporting equipment as they could and send it to France, so the local boys could play a little baseball or football in their idle hours before battle. Clarkin, who owned the Eastern League's Hartford Senators, made the trip to Boston's Fenway Park just as the Red Sox and Cubs were arriving from Chicago to finish the World Series, held early that year because of The Great War.

After the Red Sox won Game 4, Clarkin made his pitch. Suppose, when the Series was over, the Red Sox and Cubs made the short trip to Hartford for a rematch, play a game or two to raise the money for the equipment. He offered each team $1,000, and a piece of the gate to divvy up, the rest of the proceeds going to buy bats, gloves and balls for Hartford's Doughboys.

With attendance down because of the war, the players were going to be getting a smaller-than-usual World Series share, a little over $1,100, and were not happy about it, threatening a strike to stop the Series. Maybe they'd be interested in making a few extra bucks to make up for it?

Clarkin struck out. Many players were going into the Army or off to fulfill "work or fight" orders in factories, and others just wanted to go home.

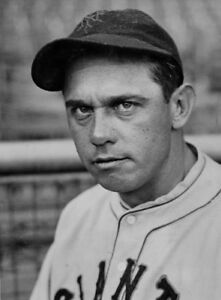

But Babe Ruth liked the idea.

So Clarkin did not return to Hartford empty-handed; he had plans in place for Ruth and a group of major-leaguers to take a barnstorming trip through New England, with two stops in Hartford the week after the Series. Surely The Babe, already the biggest attraction in baseball at age 23, would pack them in. He even donated the ball he had socked for the triple during the World Series to be auctioned off for the cause.

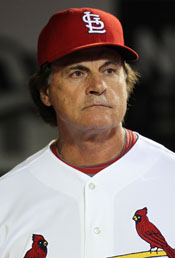

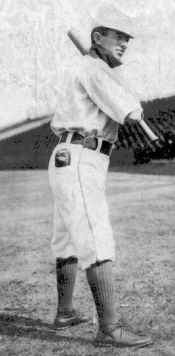

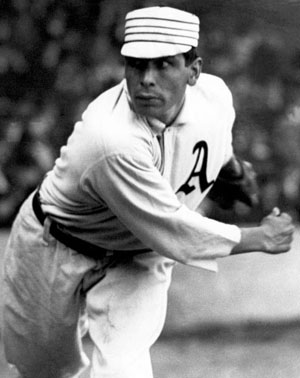

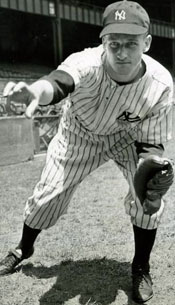

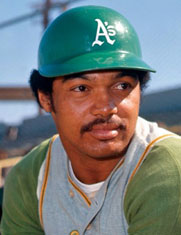

L-R: Babe Ruth, Fenway Park in 1918 But there was one thing no one seemed to consider - the pandemic storming through New England at the very same time. The Spanish Flu, which caused havoc in the spring, had returned in a more deadly second wave, spreading from Boston's Fort Devens and ripping through the city that September.

"As the World Series was played in Boston September 9, 10, and 11, by that time, we know what's going on - it's spreading," said Randy Roberts, co-author of War Fever: Boston, Baseball and America in the Shadow of the Great War. "And clearly, what is shown by this barnstorming tour is that people weren't paying attention. We shouldn't have been in large crowds."

There were warnings from health officials - but not the restrictions of the coronavirus of 2020 - to get between Ruth and his adoring fans in Connecticut. If there were two things that just couldn't go together, it was Babe Ruth and "social distancing." The Babe lived to draw crowds, and to monetize his popularity with post-season barnstorming tours for fans who would otherwise never get to see him.

On September 11, the players grudgingly decided to play and the Red Sox clinched the 1918 World Series. Three days later, Ruth arrived in New Haven to play first base for the Colonials ... The opponents were a team of all-stars from the Negro leagues, who won 5-1, but Ruth homered. ...

After the game in New Haven, Ruth was driven to Hartford, about 40 miles away, in a luxury car draped in the American flag. He arrived at a crowded lobby at the Hotel Bond, where a reception was planned, but Ruth was tired and uncharacteristically went to bed early. He was pitching the next day.

Ruth, The Hartford Courant reported, was to receive $350 for the appearance at the Hartford Baseball Grounds on September 15. ... Extra trolleys were added that day to make it easy for out-of-town fans to reach Hartford, and 5,000 filled the park.

Yet even as this was happening, doctors were making house calls and the hospitals in the city were getting crowded treating victims of the influenza, or "the grip."

It was the worst possible time to be pressed up against other fans at a ballgame. But who could resist going out to see Ruth? ...

By all accounts, it was a great day. Ruth pitched the whole game, outdueled Leonard, 1-0, and his long drive in the eighth inning conked off the "Bull Durham" sign in deep CF, going for a double.

In addition to the gate, Ruth's ball was auctioned off for $195, and a Ty Cobb bat for nearly as much.

However, by the end of the week, there were 500 people in Hartford Hospital with the Spanish Flu.

"The spread of the disease is regarded as phenomenal by physicians," The Courant reported on September 21. "It is believed that the first case did not appear a week ago. In this short time, practically the whole city has been exposed to the contagion."

The virus was approaching Hartford from the northeast, with people returning from Boston, and from the southeast, where a severe outbreak had been reported at the docks in New London, where soldiers were coming and going.

It was right in that week of the 15th to the 22nd that the numbers exploded around Boston. So the timing of 500 cases in Hartford by the end of the week matches what was happening next door.

Ruth and his traveling troupe of major-leaguers traveled 25 miles north to Springfield for a game during the week, then returned to Hartford for September 22.

"It's the patriotic duty of anyone taken with the disease to isolate himself or herself," read a warning from John T. Black of the Connecticut Board of Health. "Public gatherings held indoors should be avoided."

On the day before the scheduled doubleheader, The Courant reported, "Wherever people are crowded together, as in the trolley cars and similar places, all are likely to be exposed and a large percentage of cases will result. It may even be necessary to close the theaters and other amusement places if the epidemic grows as it has in the past few days."

But even as the local papers were pleading with people to avoid big crowds, they were tempting the locals to come out and see Babe Ruth, and for this second appearance 3,000 came to the park. The gates were open and children swarmed the outfield to watch from the warning track.

Players were taking ill even as the doubleheader was being played. SS Larry Kopf, who played for the Cincinnati Redlegs, played in the first game, came out in the late innings and sat out the second. It was reported he had the Spanish Flu, but he recovered to help the Reds win the tainted World Series a year later.

Ruth again pitched for Poli's, but this time Ruth lost 1-0. ...

After the second game, Ruth and the boys left town and scattered, a little richer, and having raised enough money to send the sporting goods overseas. Ruth traveled to Bethlehem PA to work in a steel mill, though his primary job was to play ball for the company team.

He played one game, then went to stay with family in his hometown of Baltimore. Ruth had the Spanish Flu, the Baltimore Sun reported. He recovered fairly quickly and shattered the home run record with 29 in 1919, his last season with the Red Sox.

It was only at the start of October that states such as Connecticut began to respond to the health crisis the way they did when COVID-19 hit 102 years later. Public events, such as fairs and football games, churches, schools and war bond drives were canceled and the wearing of cotton muslin masks was urged. But more than 5,000 flu-related deaths were recorded in Connecticut by the end of October, and eventually the pandemic of 1918 would claim 9,000 lives, or one percent of the state's population.

In the U.S., there were 675,000 deaths, more than the total on both sides in the Civil War. My Greatest Day in Baseball: Carl Hubbell

My Greatest Day as told to John P. Carmichael and other noted sportswriters (1945)

"King Carl" Hubbell was one of the most efficient left-handers in the majors, and to prove it the records show he won 253 and lost 154 in 16 years with the New York Giants. He mastered the screwball to the point where it was compared to the fadeaway of the immortal Christy Mathewson.

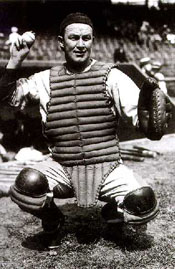

I can remember Frankie Frisch coming off the field behind me at the end of the third inning (of the 1934 All-Star Game), grunting to Bill Terry: "I could play second base 15 more years behind that guy. He doesn't need any help. He does it all by himself." Then we hit the bench, and Terry slapped me on the arm and said: "That's pitching, boy!" and Gabby Hartnett let his mask fall down and yelled at the American League dugout: "We gotta look at that all season," and I was pretty happy.

As far as control and "stuff" is concerned, I never had any more in my life than for that All-Star game in 1934. But I never was a strikeout pitcher like Bob Feller or "Dizzy" Dean or "Dazzy" Vance. My style of pitching was to make the other team hit that ball, but on the ground. It was as big a surprise to me to strike out all those fellows as it probably was to them. Before the game, Hartnett and I went down the lineup ... Gehringer, Manush, Ruth, Gehrig, Foxx, Simmons, Cronin, Dickey, and Gomez. There wasn't a pitcher they'd ever faced that they hadn't belted one off him somewhere, sometime.

We couldn't discuss weaknesses ... they didn't have any, except Gomez. Finally Gabby said: "We'll waste everything except the screwball. Get that over, but keep your fast ball and hook outside. We can't let 'em hit in the air." So that's the way we started. I knew I had only three innings to work and could bear down on every pitch.

They talk about those All-Star games being exhibition affairs and maybe they are, but I've seen very few players in my life who didn't want to win, no matter whom they were playing or what for. If I'm playing cards for pennies, I want to win. How can you feel any other way? Besides, there were 50,000 fans or more there (in the Polo Grounds), and they wanted to see the best you've got."

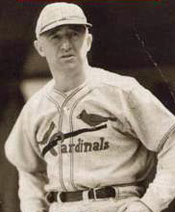

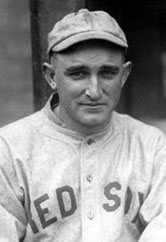

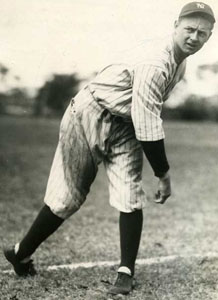

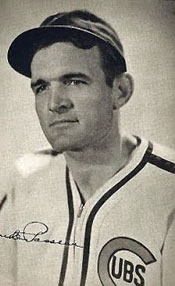

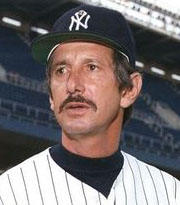

L-R: Carl Hubbell, Frankie Frisch, Bill Terry, Gabby Hartnett Gehringer was first up and Hartnett called for a waste ball just so I'd get the feel of the first pitch. It was a little too close, and Charley singled. Down from one of the stands came a yell: "Take him out!" I had to laugh.

Terry took a couple of steps off first and hollered: "That's all right," and there was Manush at the plate. If I recollect rightly, I got two strikes on him, but then he refused to swing any more, and I lost him. He walked. This time Terry and Frisch and "Pie" Traynor and Travis Jackson all came over to the mound and began worrying. "Are you all right?" Bill asked me. I assured him I was. I could hear more than one voice now from the stands: "Take him out before it's too late."

Well, I could imagine how they felt with two on, nobody out and Ruth at bat. To strike him out was the last thought in my mind. The thing was to make him hit on the ground. He wasn't too fast, as you know, and he'd be a cinch to double. He never took the bat off his shoulder. You could have pushed me over with your little finger. I fed him three straight screwballs, all over the plate, after wasting a fast ball, and he stood there. I can see him looking at the umpire on "You're out," and he wasn't mad. He just didn't believe it, and Hartnett was laughing when he threw the ball back.

So up came Gehrig. He was a sharp hitter. You could double him, too, now and then, if the ball was hit hard and straight at an infielder. That's what we hoped he'd do, at best. Striking out Ruth and Gehrig in succession was too big an order. By golly, he fanned ... and on four pitches. He swung at the last screwball, and you should have heard that crowd. I felt a lot easier then, and even when Gehringer and Manush pulled a double steal and got to third and second, with Foxx up, I looked down at Hartnett and caught the screwball sign, and Jimmy missed. We were really trying to strike Foxx out, with two already gone, and Gabby didn't bother to waste any pitches. I threw three more screwballs, and he went down swinging. We had set down the side on 12 pitches, and then Frisch hit a homer in our half of the first, and we were ahead.

L-R: Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmy Foxx, Al Simmons, Joe Cronin It was funny, when I thought of it afterwards, how Ruth and Gehrig looked as they stood there. The Babe must have been waiting for me to get the ball up a little so he could get his bat under it. He always was trying for that one big shot at the stands, and anything around his knees, especially a twisting ball, didn't let him get any leverage. Gehrig apparently decided to take one swing at least and he beat down at the pitch, figuring to take a chance on being doubled if he could get a piece of the ball. He whispered something to Foxx as Jim got up from the batter's circle and while I didn't hear it, I found out later he said: "You might as well cut ... it won't get any higher." At least Foxx wasted no time.

Of course the second inning was easier because Simmons and Cronin both struck out with nobody on base and then I got too close to Dickey and he singled. Simmons and Foxx, incidentally, both went down swinging and I know every pitch to them was good enough to hit at and those they missed had a big hunk of the plate. Once Hartnett kinda shook his head at me as if to say I was getting too good. After Dickey came Gomez and as he walked into the box he looked down at Gabby and said: "You are now looking at a man whose batting average is .104. What the hell am I doing up here?" He was easy after all those other guys and we were back on the bench again.

We were all feeling pretty good by this time and Traynor began counting on his fingers. "Ruth, Gehrig, Foxx, Simmons, Cronin! Hey, Hub, do you put anything on the ball?" Terry came over to see how my arm was, but it never was stronger. I walked one man in the third ... but this time Ruth hit one on the ground and we were still all right. You could hear him puff when he swung. That was all for me. Afterwards, they got six runs in the fifth and licked us, but for three innings I had the greatest day in my life. One of the writers who kept track told me that I'd pitched 27 strikes and 21 balls to 13 men and only five pitches were hit in fair territory. Homer History

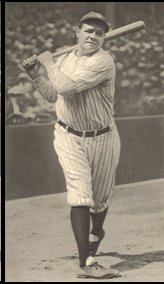

One hundred years ago, Babe Ruth fundamentally changed baseball into what is still today's standard.

Scott Pitoniak, Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the Hall of Fame (Winter 2020) In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the baseball cognoscenti paid short shrift to the long ball. "Small ball" was in vogue. Placement rather than distance was emphasized. Many players choked up on the bat and - in the immortal words of 5-foot-4 Hall of Fame outfielder Wee Willie Keeler - tried to "hit 'em where they ain't." The goal was to scratch out a run through a series of at-bats. Get runners on. Move them along with bunts, stolen bases and hit-and-run plays. Manufacture offense.

Small ball was born out of necessity during this aptly named Dead Ball Era, when a single beaten-to-death-by-the-third-inning baseball would be used throughout the game, no matter how mushy or blackened it became. It was a ball, too, without cork at its core; a spheroid not designed to fly like a current baseball.

That's not to say home runs didn't occur in those bygone days. They did, by the hundreds each season. But power ball was considered "stupid" by many. Conventional wisdom said fly balls usually resulted in outs. For the longest time, home runs weren't even included in box scores. That's how lowly they were regarded.

Then, on the brink of the Roaring Twenties, a man who would become known as the Sultan of Swat - and at least 50 other nicknames - exploded onto the scene. Babe Ruth would make an indelible impression on horsehides and fans. After decades of being an afterthought, the home run became the most dynamic weapon in baseball and a permanent part of American culture, language and lore.

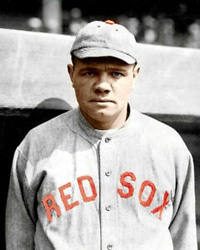

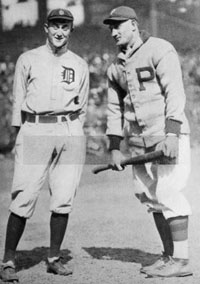

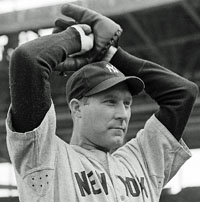

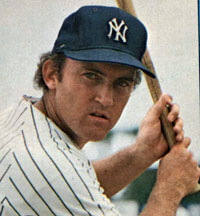

L-R: Wee Willie Keeler, Babe Ruth, Ned Williamson Ruth's big bang theory proved once and for all that hitting a homer is the best possible thing a batter can do in an at-bat. With one swing, a slugger could produce a run, and several more, depending on the number of base runners. A home run was instant offense. An exclamation point.

In 1919, Ruth set a single-season Major League Baseball record with 29 homers, breaking Ned Williamson's 1884 mark by two. The next year, the Bambino obliterated his own standard hitting 54. To put his otherworldly achievements into perspective, he out-homered all but one of the other 15 big league teams. And that team, the Philadelphia Phillies, hit 64 home runs in the tiny Baker Bowl.

Fans fell in love with Ruth - and the home run - as his 1920 New York Yankees became the first professional sports team to draw more than a million spectators. And Ruth would have a pied piper effect on other hitters, who followed his lead and began swinging for the fences every time they stepped to the plate.

Today, a century later, baseball's homer odyssey continues at a dizzying, record-smashing pace. The game that Ruth built saw 6,776 home runs smacked in 2019, exceeding by 671 the previous MLB mark established just two years earlier. And that skyward trend figures to continue, when you factor in bigger, stronger players; smaller, hitter-friendly ballparks; livelier baseballs; and analytics that show an all-or-nothing approach is the best strategy, even if it means a drastic increase in strikeouts.

Thanks to modern-day mashers like Mike Trout, Mookie Betts, Aaron Judge and Fernando Tatis Jr., and data-crunching Sabermetricians obsessed with launch angles and exit velocity, small ball has been sent packing.

To paraphrase some famous home run calls: "It's gone - and it ain't coming back. Kiss it goodbye."

The Babe's perfect storm

Timing, they say, is everything in life and in baseball, and that certainly was the case with Ruth, whose timing proved impeccable. His arrival coincided with a triple play of good fortune that contributed to him lifting baseballs and his sport to heights not witnessed before.

Certainly the biggest part of the equation was Ruth's brutish strength, surgical hand-eye coordination and fluid, left-handed swing reportedly modeled after Shoeless Joe Jackson, one of the marquee hitters of the early 20th century. But the Bambino also benefitted from the introduction of the livelier ball, the elimination of the spitball and other trick pitches, and the frequent replacement of worn baseballs with new ones throughout the game.

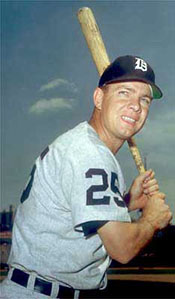

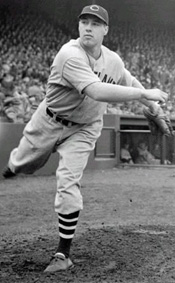

L-R: Joe Jackson, Ray Chapman, Carl Mays, Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner The cork-centered baseball was used full-time starting in 1911, and though it didn't result immediately in a long-ball game, it would set the stage. Balls doctored with spit, tobacco juice, gels and other foreign substances gave pitchers a decided edge, so the elimination of this practice in 1920 swung the advantage back to batters. And the accidental beanball death of Ray Chapman on an errant pitch by Carl Mays on Aug. 16, 1920, forced MLB to seek ways to make the game safer. This resulted in smudged balls being thrown out of play and replaced with new ones that were easier for batters to see.

And when he was acquired by the Yankees, Ruth found the short right field fences at the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium a perfect fit for his swing.

Ruth's rebellious nature also was a factor. Despite being regarded as the American League's top left-handed pitcher, he insisted on becoming an everyday player so he could do what he enjoyed doing best. His slugging defied the "scientific" small-ball strategy preached by Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Napoleon Lajoie and other star players of that era. Cobb, in particular, would ridicule him, but the Babe would get the last laugh. "If I just tried for them dinky singles, I could've batted around .600," Ruth sneered.

His goal was 60, not .600, and after clubbing 59 homers in 1921, he would reach his magical mark six years later. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and Josh Gibson, Jimmie Foxx, Hack Wilson and Lou Gehrig were among the many who began mimicking Ruth. Not surprisingly, home run totals more than doubled during the decade.

"By the fall of 1927, Babe Ruth had completely reshaped the game of baseball, bending it to his will," author Jane Leavy wrote in her bestselling book The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created. ... Subtlety was banished. Clout was all. Ruth had taught America to think big - expect big."

Launchers of homers would become baesball's biggest stars. As Fritz Ostermueller opined in a quote often attributed to his Pittsburgh Pirates Hall of Fame teammate Ralph Kiner: "Home run hitters drive Cadillacs; singles hitters drive Fords."

Origin of the Slider

A History of Baseball in Ten Pitches,Tyler Kepner (2019)

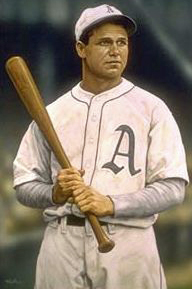

The origins of the slider, as we know it now, are murky. In 1987, hundreds of former players responded to surveys for a book called Players' Choice. They answered many questions, including the best slider of their day. Pete Donohue, a three-time 20-game winner for the Reds in the 1920s, could not give a name: "We didn't have one when I pitched," he replied.

Hmm–but what is this pitch, if not a slider? "It was a narrow curve that broke away from the batter and went in just like a fastball," said the great Cy Young, describing a pitch he threw in a career that ended in 1911.

Contemporaries of Young, like Chief Bender, an ace of the early Philadelphia A's, probably threw it, too. Bender's name virtually demanded he not throw straight, and he was, you might say, the chief bender of pitches in his era. Listing his repertoire for Baseball Magazine in 1911, Bender first mentioned his "fast curves," which would seem pretty close to what we now call a slider. George Blaeholder and George Uhle, whose careers ended in 1936, were early pioneers. Blaeholder, who pitched mostly for the Browns, had sweeping action on his fastball that was said to baffle Jimmie Foxx. Uhle, a 200-game winner, developed the slider late in his career, after his prime with the 1920s Indians. It startled Harry Heilmann, a Detroit teammate who was hitting off Uhle in batting practice.

"What kind of curve is that?" Heilmann asked.

"Hey, that's not a curve," Uhle replied. "That ball was sliding."

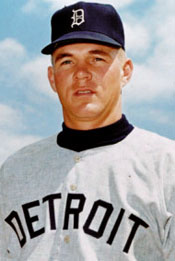

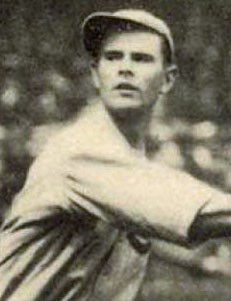

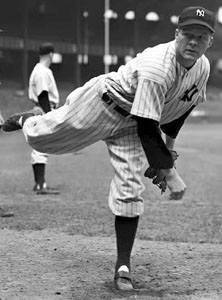

L-R: Pete Donohue, Chief Bender, George Blaeholder, George Uhle Waite Hoyt, an admiring teammate and the ace of the fabled 1927 Yankees, compared its action to a car skidding on ice. He added the pitch himself and credit Uhle for inventing it. Uhle told author Walter Langford that, as far as he knew, he threw it first.

"At least I happened to come up with it while I was in Detroit," he said. "And I gave it its name because it just slides across. It's just a fastball you turn loose in a different way. When I first started throwing it, the batters thought I was putting some kind of stuff on the ball to make it act that way."

Red Ruffing used a slider in his Hall of Fame career, which include four 20-win seasons in a row for the Yankees from 1936 through 1939. In that final season, the National League MVP was the Reds' Bucky Walters, a former third baseman who had learned a slider a few years earlier from Bender, a fellow Philadelphian. Walters led his league in all the major categories in 1939, and the next year lifted the Reds to their only World Series title between the Black Sox and the Big Red Machine–a span of 55 seasons.

L-R: Waite Hoyt, Red Ruffing, Bucky Walters, Spud Chandler In 1943, another MVP threw the slider: the Yankees' Spud Chandler, who shut out the Cardinals to clinch that fall's World Series. Chandler had learned the pitch from Ruffing, whose influence Rob Neyer and Bill James cited as a reason the slider soon made a breakthrough. The other factors, they said, were Walters' success and the fact that the pitch now had a name; it was not just another breaking ball. After three years at war, Ted Williams noticed the trend:

We began to see sliders in the league around 1946 or 1947, and by 1948 all the good pitchers had one. Before that there were pitchers whose curves acted like sliders. Hank Borowy threw his curve hard and it sank and didn't break too much, so it acted like a slider. Johnny Allen's was the same way. Claude Passeau's fastball acted like s slider.

Williams called the slider "the greatest pitch in baseball," easy for a pitcher to learn and control. He worried about grounding the slider into the infield shift, reasoning that the only way he could put it in the air was by looking for it. Most hitters are late on the fastball if they sit on the slider, but Williams was not like most hitters. He batted .419 off the Browns' Ned Garver and .377 off the Tigers' Jim Bunning, who otherwise thrived with sliders.

"The big thing the slider did was give the pitcher a third itch right away," Williams wrote in his book, My Turn at Bat. "With two pitches you might guess right half the time. With three, your guessing goes down proportionately."

Williams believed the popularity of the slider helped drive averages down. Bob Feller, the best pitcher Williams said he ever saw, had fiddled with the slider in 1941, and perfected it by the time he returned from the war. Mixing a slider with his devastating fastball and curve in 1946, Feller struck out 348–then considered the American League record. He described the pitch like this:

It can be especially effective for a fast ball pitcher because it comes up to the plate looking like a fast ball. It has less speed, but not enough for the hitter to detect the slightly reduced speed early in the pitch.

The slider darts sharply just before it reaches the plate, away from a right-handed hitter when thrown by a right-handed pitcher. It doesn't break much–four to six inches–but because it breaks so late, the hitter has trouble catching up to it. I didn't invent the slider–I merely popularized it. The pitch has been around since Christy Mathewson's time.      L-R: Ted Williams, Hank Borowy, Johnny Allen, Claude Passeau, Bob Feller The slider's transformative power showed up in Feller's statistics, and in his clubhouse. Phil Rizzuto said that in his rookie season, 1941, the only pitcher he faced who threw sliders regularly was Al Milnar of the Indians. Feller was on that team, and so was Mel Harder, who taught the slider a few years later to Bob Lemon, who went on to the Hall of Fame. The logic behind the pitch was so easy to understand, and the pitch itself so simple to learn–generally, but not always: off-center grip, pressure applied to the middle finger, and possibly a late, subtle wrist snap–yet there remained an odd kind of backlash against it into the 1950s.

Pitchers threw fastballs and curveballs, sometimes a trick pitch like a knuckleball, and a spitball if they could conceal it. The conventional wisdom was that learning a slider would harm a pitcher's curveball. A curveball demands a different arm action–wrapping the wrist and pulling hard, straight down, to generate furious topspin. Throw too many sliders and you might lose the feel for staying on top of the curve.

"If you have a good curve, it's foolish to add the slider," said Sal Maglie, a curveball master who was turned away from using a slider by Uhle for that reason. "But all the young pitchers today are lazy. They all look for the easy way out, and the slider gives 'em that pitch."

Maglie said this in 1962, in an Esquire article that included his assertion that Roger Maris had feasted off sliders while blasting 61 homers the year before. To Maglie, expansion and "all the second-line pitchers in the league throwing sliders" had added at least 10 homers to Maris's total. The pitch was widely derided as a "nickel curve"–a breaking ball, yes, but a cheap knockoff of the real thing. That term is long gone, but "cement mixer," which describes a lazy and obvious slider, persists today.

The critics of the slider were blind to its impact. In his book Head Game, Roger Kahn asserted that the slider "saved major league baseball from becoming extended batting practice" after the offensive boom of the 1930s. That era had its masters–Lefty Grove, Dizzy Dean, Carl Hubbell–but few others were much better than ordinary. The slider gave pitchers a weapon they could learn and control with relative ease, a pitch that looked like a fastball much longer than the curveball did.

"I could always tell a curveball from a fastball in the first 30 feet of flight," Stan Musial told Kahn. "I picked up the speed of the ball and I'd know just what the ball was going to do. Break or hop. The slider was tougher. I get my share of hits off sliders. But during the years I played for the Cardinals, the slider changed the game."

You Have to Threaten the Bottom Line - 1

Bill White with Gordon Dillow, Uppity: My Life in Baseball (2011)

White was the Cardinals first baseman from 1959-1965.

You Have to Threaten the Bottom Line – 2

Bill White with Gordon Dillow, Uppity: My Life in Baseball (2011)

Read Part 1. Within days of my comments being published, with talk of a Budweiser beer boycott in the air in the black community, I got a visit in St. Petersburg from my old minor league manager Eddie Stanky, who was working in the Cardinals' front office. When he walked into the clubhouse, everybody wondered what Eddie was doing there, but I knew immediately.

Eddie invited me to go fishing, and that afternoon on a little outboard motorboat on Tampa Bay, Eddie got down to business.

"I know you have some concerns about this housing issue, Bill," he said. "But this is bringing a lot of heat on the company [Anheuser-Busch] and the team. We really need you to back off. Can't you just concentrate on baseball for now, and leave politics out of it?"

I had always liked Eddie and still did. But I wasn't going to back down.

"You know I have a lot of respect for you," I told him. "But no, I'm not going to back off, not on this issue. What's going on in St. Petersburg is wrong, and as long as black players in spring training are made to feel inferior, I'm going to speak up."

I think Eddie understood. And though he couldn't say so publicly, I think he actually respected what I was doing.

I also got a visit from a guy named Roscoe McCrary, a reporter for The St. Louis Argus, a black newspaper in which Anheuser-Busch advertised heavily. Roscoe said he wanted to do a story on me, but I could tell from the softball tone of his questions that he wanted me to downplay complaints about conditions for black ballplayers in St. Petersburg.

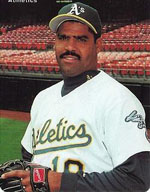

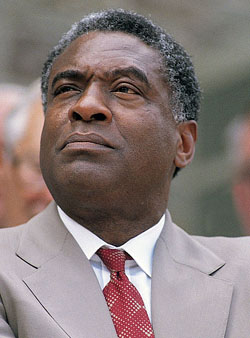

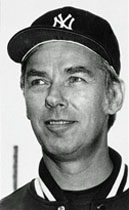

L-R: Al Fleishman, Elston Howard, Dr. Ralph Wimbish, Bill White as NL President "Listen, Roscoe," I said, "this is not a good place for us to have spring training. If you try to soften up what's going on down here just to help a big advertiser, you'll be doing all of us a disservice. If you do that, I won't be happy–and believe me, I'll let people in St. Louis know that you're trying to sugarcoat this."

Roscoe got the message. His subsequent story wasn't as hard hitting as I would have liked, but he didn't sugarcoat what I said.

And finally I got a visit from one of the big guns, Al Fleishman, head of the Fleishman-Hillard public relations agency, which represented the brewing company. But as it turned out, Al's message wasn't exactly the one the company wanted.

"They wanted me to tell you to cool down," Al told me. "But the hell with that. The last thing you want to do now that you've got their attention is to cool down. You need to keep pressure on their ass."

Al was a good guy, and like a lot of Jewish Americans, he had no patience with racial and ethnic bigotry. It probably didn't help Al's mood that many hotels in St. Petersburg excluded not only blacks but also Jews.

Meanwhile, fearful of losing the millions of dollars that spring training brought into the local economy, the St. Petersburg Chamber of Commerce backed down. Insisting that it had all been an unfortunate mistake, they invited me and another black player, Elston Howard of the Yankees, to the Salute to Baseball breakfast at the yacht club.

The Yankees ordered Elston to attend, and Dr. Wimbish (president of the St. Petersburg NAACP) and others urged me to go as well. But I knew the chamber and the yacht club weren't advocating full integration. The club still wouldn't let NAACP member Dr. Swain dock his boat there. I wanted to let them known that I had a choice–and my choice was not to go.

I hadn't wanted to eat with those bigots anyway. All I had really wanted, what all the black players wanted, was simply the opportunity to say no.

The end result of all this was that while Cardinals management initially tried to downplay the race issue, eventually the public pressure was too great, not only on the Cardinals but on all the teams. The Cardinals finally demanded that the Vinoy Park Hotel open itself to black players.

The hotel refused, so in order to help keep spring training in St. Petersburg, a local businessman bought a beachfront motel called the Outrigger and made it available to all Cardinals players and their families, black and white. As a show of solidarity, players who usually stayed in private beachfront homes, like Stan Musial and Ken Boyer, also moved into the Outrigger.

So by the start of spring training in 1962, all the Cardinals were living under the same roof and eating at the same on-site restaurant. For the first time, black players felt comfortable bringing their families to spring training. Our kids went to integrated events organized by the players' wives. Black players and white players and their families were even swimming in the same pool. All this integration was so unheard of in Florida that people would drive by the motel all day just to gawk and stare.

The whole controversy helped black players realize that they had power–or at least some public leverage. When Southern cities like Houston and Atlanta were trying to get major league teams, Milwaukee Braves CF Billy Bruton and I got the Major League Baseball Players Association to vote unanimously not to play in any city that required black and white players to use separate living facilities.

Of course, ending separate living arrangements for baseball players in Florida didn't end segregation altogether. Over the next few years, and especially after passage of the 1964 federal Civil Rights Act that banned discrimination in public facilities, Dr. Wimbish would often recruit me and other black players while we were in St. Petersburg for spring training to help break the now illegal, but still very real, color barrier in local restaurants.

Dr. Wimbish would stop by the Outrigger and pick up Bob Gibson and me and say, "Tonight we're going to integrate this restaurant," or "Tonight we're going to this 'whites-only' club." We'd walk in and order a drink or some food, and while we got a lot of looks, no one ever gave us any trouble. We always dressed nicely, spoke in quiet tones, and in general acted respectably. Later Bob said it was like having dinner with a new girlfriend's parents night after night; you always had to be on your best behavior.

I've always been proud of what I did back then, that I had spoken up. Once again, no one person ever single-handedly defeats widespread social injustice; that takes millions of hands. Still, the spring training controversy focused a lot of attention on me.

And of all the messages of support I received, there is one that stands out. It came in the form of a letter from a man I had never gotten to know very well, but one whom I deeply admired, a man who had suffered greatly in the cause of equality. Today the letter remains one of my most cherished possessions.

"Dear Bill," the letter said. "I just wanted you to know that I appreciate everything that you've done for black baseball players. Keep up the fight."

The letter was signed, "Jackie Robinson."

Postscript: In 1989, in a unanimous vote, Bill White was elected to replace new Baseball Commissioner Bart Giamatti as National League president.

Another Hemorrhoid

Damned Yankees: A no-holds-barred account of life with "Boss" Steinbrenner,

Bill Madden and Moss Klein (1990) It is doubtful if there was ever a more sour person to pass through the Steinbrenner asylum than Doyle Alexander, the much-traveled right-handed pitcher. Maybe that was because Alexander knew he was a misfit with the Yankees and resented not being somewhere else where he could just go out and pitch and be left alone. Actually, Alexander had two tours of duty in The Bronx, neither of them of his own choice, which undoubtedly had a lot to do with his sullen disposition.

In 1976 Alexander was traded to the Yankees in midseason from the Baltimore Orioles and wound up the surprise starter in the first game of the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds, as Billy Martin had run through all his more highly regarded starters in the playoffs versus Kansas City. Alexander was bombed for nine hits and five runs in six innings in that game and, if nothing else, was probably satisfied he had pitched his last game as a Yankee. Shortly after the season, he filed for free agency and fled to Texas and the perennially last-place Rangers. After a couple of years in Texas, Alexander moved on to Atlanta and eventually San Francisco, where he was about as far away from the Yankees as one could hope for.

As he did almost every place he went, however, Alexander became embroiled in a contract dispute in the spring of 1982. And like all of Alexander's previous employers, the Giants decided they didn't want the headache of trying to re-sign disgruntled Doyle. So they called the Yankees and Steinbrenner, who were more than willing to take Alexander back ... so willing that they signed him to a new four-year contract worth $2.2 million.

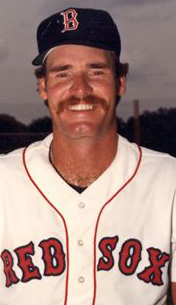

L-R: Doyle Alexander, Billy Martin, George Steinbrenner It took a few days to complete the trade because of Alexander's contract demands, but on March 30 the deal was announced that Alexander was coming back for a couple of minor league prospects. Bill Madden had been tipped off about the trade a day earlier and called manager Bob Lemon in his hotel room to ask him about it.

"I hear you've got yourself a new starting pitcher," Madden said.

"Oh, yeah?" said Lemon. "Who am I getting?"

"Doyle Alexander," replied Madden.

There was a brief moment of silence at the other end of the phone.

"Just what I need," said Lemon, "another hemorrhoid."

With that, Lemon said he wanted to back to watching "Barnaby Jones," his favorite TV show, which helped him take his mind off the every-growing loony bin he was being asked to preside over that spring.

The next day, as word of Alexander's second coming circulated around the Yankee camp, Lemon's sentiments seemed to be shared by a few others. Moss Klein was talking to Graig Nettles in the clubhouse and told him how Steinbrenner predicted Alexander would win 15 games for the Yankees.

"Fifteen?" said Nettles. "Hmmm. How many years did George give him?"

"Four," said Klein.

"Yeah, well," deadpanned Nettles, "in that case he might win 15."

As it turned out, Nettles's dire assessment wasn't even close to the mark. Alexander won one game for the Yankees in his second go-round with them. Then again, he didn't make the four years either. He was released after a year and two months with them, only to resume his career as a quality pitcher with the Toronto Blue Jays.

L-R: Bob Lemon, Graig Nettles, Gene Michael Alexander was anything but a quality pitcher for the Yankees. Whether he just didn't want to be there or whether he just couldn't adjust to life in the Yankee fishbowl, Alexander could do nothing right in pinstripes.

After missing most of spring training because of his contract dispute, Alexander stayed behind in Fort Lauderdale to pitch himself into shape and didn't make his first start until April 24. He never could seem to get on track, though, and was large ineffective in his first two starts.

In his third start, against the Mariners in Seattle, he was the victim of a five-run third inning in which four of the runs were unearned. Furious over having to come out of the game at that point, Alexander came into the dugout and punched the wall, breaking a knuckle on his pitching hand. The self-inflicted injury knocked him out of action for six weeks, and he got no sympathy from the Yankee high command.

"I don't feel sorry for him at all," said Yankee manager Gene Michael. "It was a dumb thing to do ... one of the dumbest things I've ever seen. How a pitcher who's been around as long as he has can punch a wall with his pitching hand is beyond me. We needed him. He was important in our plans, and he's not only hurt himself, he's hurt the team."

Initially, Alexander agreed with Michael's harsh assessment of the mishap and, instead of waiting to be fined by the club, offered to return a month's pay to the Yankees for his mistake. But then union chief Marvin Miller and the Players Association stepped in and said that would be a dangerous precedent for a player to set. Alexander agreed and informed the Yankees he was rescinding his offer.

The Yankees wound up fining Alexander $12,500 for his painful experience, but that was not the end of it. Toward the end of his recuperation period, Alexander went to Columbus, the Yankees' AAA farm team, to pitch his way back into shape. When Steinbrenner requested him to stay awhile longer in the minors to be certain he was ready, however, Alexander refused.

Steinbrenner was incensed. He ordered Alexander's activation on June 9 and told manager Michael to pitch him right away. Alexander pitched that night against the Athletics in Oakland and was pummeled for five runs and five hits, retiring only four batters. Afterward Yankee GM Bill Bergesch issued a stinging indictment of Alexander that had obviously been dictated by Steinbrenner.

"George said he is sorry he signed Alexander off the recent series of events," Bergesch said. "If we could trade him tomorrow, George said he would authorize me to do it. What Doyle Alexander did tonight was disgraceful, but typical of the selfishness of some of the modern-day ball players."

Michael followed that up by announcing that Alexander was going to have to pitch his way back into the rotation by going to the bullpen.

"It's their team, and they can do with it what they want," said Alexander. "I'm not looking for a verbal war with these guys. I'm available to pitch if they want me."

It seemed impossible that Alexander's season could deteriorate any further than that point. Nevertheless, he continued to pitch poorly, while blaming his performance - perhaps with some justification - on his irregular pitching schedule.

On August 10 Alexander reached his nadir as a Yankee, and Steinbrenner reached his zenith as a statement writer. The Yankees were playing the Tigers in Detroit, having won four of their last five games under new manager Clyde King. On Alexander's first pitch of the game, Tiger 2B Lou Whitaker homered into the LF seats. Two more homers would follow in a six-hit, six-run barrage that drove Alexander to the showers after just three innings.

From his home in Tampa, Steinbrenner furiously dictated a statement to Bergesch that, even by the principal owner's standards, was outrageous. Usually the reaction in the press box to Steinbrenner statements is either ridicule or disinterest, but this one brought looks of astonishment from one and all before the hilarity began to set in. "After what happened tonight," Steinbrenner said, "I'm having Doyle Alexander flown back to New York to undergo a physical. I'm afraid some of our players might get hurt playing behind him. He steadfastly refused to go back to Columbus another time to pitch his way back into shape. That's okay if you back it up with solid performance. But Alexander has given up eight homers in 38 innings, and in his last two starts he's given up 11 runs in five innings. Obviously something is wrong and we intend to find out."

After the game reporters flocked to Alexander for his reaction to this latest and most stinging blast from Steinbrenner.

"It's obvious I'm not pitching well," Alexander said calmly. "I'm not pitching the way I can, and I regret that for the fans and my teammates."

What about the physical?

"I think it's a good move," Alexander said, adding much to the surprise of everyone that he agreed to do it. "But I want to make it plain this is with a medical doctor, not a psychiatrist. A lot of people are going crazy around here, but I'm not there yet."

Goose Gossage echoed that remark by saying, "Doyle's getting a physical, but George needs a mental."

As for Steinbrenner's fears for the safety of his players when Alexander was pitching, Nettles gave assurances that wasn't a problem.

"I wasn't worried," Nettles said. "Maybe I might have been if I was sitting in the left field stands."

Alexander finished the '82 season with a 1-7 mark and 6.08 ERA. Undoubtedly, Steinbrenner would have liked to follow his inclination earlier in the year and trade the disappointing pitcher, but with that record and that salary, Alexander had virtually no value on the trade market. As a result, when spring training began in February of 1983, he was back with all the other Yankee pitchers in Fort Lauderdale.

Numbers King

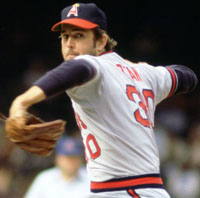

Nolan Ryan's Strikeout Achievements Still Fill the Record Books

Scott Pitoniak, Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the Hall of Fame (Winter 2021)

Retaliate or Not?

From 3 Nights in August: Strategy, Heartbreak, and Joy Inside the Mind of a Manager,

Buzz Bisinger (2005)

Very Superstitious - 1

Joe Trezza, 2018 World Series Program

From lucky gum to spicy salsa, baseball's long history of rituals makes everything more interesting. The long, storied history of baseball superstitions took a spicy turn in 2018, the sentiment that connects it all - from curses and billy goats to black cats to codes of silence - reemerging under the spring sun of a suburban St. Louis backyard. That's where Cardinals infielder Matt Carpenter, mired in a career-worst slump at the time, literally planted the seeds for what would become one of the more sensational second-half turnarounds ever.

Those seeds spawned jalapeños. They grew in a garden built for Carpenter by his longtime teammate, Adam Wainwright. Carpenter harvested them himself, and that's all he'll say about the homemade salsa he spins from them other than that, suddenly, the eight-year Major League veteran can't play a game without it.

"Since the All-Star break," Carpenter said, "I haven't missed a day."

From the outside looking in, there are myriad explanations for how the Cardinals, sputtering around .500 for the season's first 100 games, sprinted their way toward October behind a historic late-summer push. They changed their manager. They revamped their bullpen. They handed their roster over to a platoon of talented prospects. Carpenter morphed into an MVP candidate.

But for Carpenter and others in the Cardinals clubhouse, the answer is simple: It's the salsa. Mild but potent, and increasingly popular. Its powers mysterious but palpable. Carpenter began growing the ingredients in mid-May, when he was hitting .140. He started snacking on it before every game in July, at which point he'd swung himself back to a respectable .263/.373/,530 line.

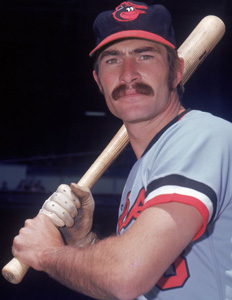

L-R: Matt Carpenter, Wade Boggs, Nomar Garciaparra, Reggie Jackson But the salsa didn't become a thing until the weeks that followed, when Carpenter began bringing it on the road, making it available to his teammates, and crediting it for his surge into the record books. There was the six-game stretch when Carpenter homered eight times (and in all six games). There was the one-week stretch when he hit. 529, and the 30-game span when he flirted with slugging .700. By the end of August, Carpenter was on the cusp of becoming the first Cardinal to notch 40 doubles and 40 homers since Albert Pujols in 2009.

Meanwhile, the Cardinals sprinted to the top of the NL Wild Card standings.

"I don't have an explanation for it," Carpenter admitted. "It's just not who I am. It's not who I was. It's not the hitter I've ever been. I'm developing into somebody I've never dreamed of or tried to be."

In the larger scope of things, Carpenter's salsa-fueled summer is less an outlier than it is a modern spin on one of baseball's most enduring themes. Baseball has always been a game bound to belief, full of conviction in vague requirements for fortune. Wade Boggs famously mapped out his pregame routine by the minutes, convinced he'd fail if he didn't adhere to its exact schedule. Nomar Garciaparra unwrapped his batting gloves after every pitch, in anxious unease.

Reggie Jackson wore the same helmet from team to team. Jim Leyland didn't change his boxers. The list goes on and on.

|