|

Baseball Profiles - 1

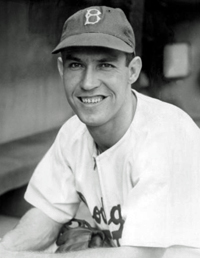

Pete Reiser

Summarized from: The Team That Forever Changed Baseball and America:

The 1947 Brooklyn DodgersEdited by Lyle Spatz Only a handful of people who saw Pete Reiser in his prime are still around today. Those who did cannot watch an athlete streak toward an outfield fence without feeling just a little sick to their stomachs. Pete was a 5-foot-10 1/2, sinewy-strong 185-pounder who generated more speed, power, and pure energy than seemed physically possible from that modest frame. The only thing that could stop Pete was an unpadded stadium wall.

Reiser was a high school shortstop. He was not big, but he was fast. He also had a powerful arm and a live bat, and he was unrelenting on defense. He believed there was no ball he could not get to. This was not a major issue in the infield, where players are encouraged to leap and dive and spin. In the outfield, where Reiser would ultimately play, his imprudence would lead to his downfall. At 15, Reiser sneaked into a St. Louis Cardinals tryout, where he out-threw and outran 800 other boys. He was disappointed when he returned home without a contract, but later a Cardinals scout, Charlie Barrett, visited the Reiser home and explained why they hadn't made a big deal about Pete at Sportsman's Park. The Cardinals didn't want word leaking out to the Browns, with whom they shared the ballpark, or anyone else. The scout also admitted they'd had their eye on him since grade school. The Cardinals knew Pete wasn't old enough to sign a contract, so they hired him as a "chauffeur." Just as planned, Reiser was signed by the Cardinals in 1937, after high school. He played shortstop for two Class D teams-New Iberia (LA) of the Evangeline League and Newport of the Northeast Arkansas League. In 1938 Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis ruled that the Cardinals' system tied up so many young players that it went against the interest of baseball. Landis broke up their Minor League monopoly by cutting loose dozens of players, who were then dispersed to other teams through a kind of Depression-era free agency. Of these players, Pete Reiser was arguably the best. More to the point, he was the one Cardinals GM Branch Rickey most wanted to keep.     L-R: Commissioner Landis, Branch Rickey, Larry MacPhail, Leo Durocher Pete followed orders, signed with the Dodgers for $100, and was sent to Superior (WI) of the Class D Northern League, where he hit .302 with 55 extra-base hits. He was still hitting right-handed at the time, but once he revealed that he was ambidextrous, coaches encouraged him to swing around to the left side, to take better advantage of his speed. He would hit almost exclusively left-handed for the better part of the next ten years. Reiser first caught the eye of the Dodgers' new player-manager, Leo Durocher, at spring training in 1939. It was a hot day and Durocher did not feel like playing shortstop. He asked Pete to play the position. What happened next is part of baseball lore. Pitchers literally could not get Reiser out. In eleven trips to the plate over three games, he collected three walks, four singles, and four home runs. Durocher, who had been pining for a left-handed power threat, had one dropped right in his lap-from Class D ball, no less! Durocher started telling the beat writers that Reiser would be his Opening Day shortstop. He was ready to take the rookie under his wing. When glowing articles started showing up in the New York papers, MacPhail received a phone call from an enraged Rickey accusing him of a double-cross. MacPhail sent Durocher a telegram instructing him to stop playing Reiser-phenom or not. He needed more instruction and was to be sent to the Minor League camp. Durocher, who hated to be second-guessed when it came to players, ignored these orders. MacPhail then boarded a flight south so he could deal with Leo face-to-face. Durocher was just as conniving as Rickey and MacPhail, but he also had a big mouth, so MacPhail was not about to tell him the real story behind Pistol Pete. An argument ensued during which MacPhail fired Durocher. The next day they settled their differences; nevertheless, Durocher could see MacPhail was serious about Reiser. He optioned Pete to the Minors as ordered. That year Reiser suffered the first of many serious injuries he would endure during his professional al career. Playing the outfield in Class A, he felt a sharp pain while throwing a ball to the infield. He continued to play for two weeks until the pain became unbearable. X-rays showed that he had fractured his arm. He underwent went an operation to remove bone chips from his right elbow, and he played in only thirty-eight games in 1939. Toward the end of the season, he returned for a few games, throwing left-handed. Reiser was back in class A to start the 1940 season, but the Dodgers realized he had nothing left to prove there. He was batting .378 when they promoted him to their top farm team, Montreal, and from there he arrived in Brooklyn and appeared in his first game on July 23. After a 0-for-9 start, he batted .293 in 58 games. Reiser worked his way into the starting lineup early in 1941, playing CF. Pete started hot and stayed hot, torturing pitchers at the plate and on the base paths, while making remarkable catches and throws in the outfield. Reiser finished the year with a .343 average to win the batting crown. He led the National League with 39 doubles, 17 triples, 117 runs scored, and a .558 slugging percentage, and finished second to teammate Dolph Camilli in voting for the Most Valuable Player Award. The Dodgers edged the Cardinals by two and a half games for the National League pennant. As good as Reiser had been in 1941, he was even better in 1942. Few who saw him in the season's first half questioned whether he would repeat as batting champ. Some -including Reiser himself - thought he could follow up Ted Williams's .406 campaign in 1941 with a .400 season of his own.  One of the many times Reiser was carried off the field on a stretcher. In this instance, he was beaned in a 1941 game. The Dodgers' lead evaporated down the stretch as St. Louis edged Brooklyn by two games. Reiser ended up batting .310, but still led the league with 20 steals. Before the injury, teammate Billy Herman - who had played with Hall of Famers Chuck Klein and Hack Wilson - said Pete was the greatest player he had ever seen. After the season, Reiser attempted to enlist in the navy, but he flunked his physical. In January 1943 he tried again, this time at an army recruiting office. He was about to be rejected when an officer recognized him and waved him through. If baseball was tough on Reiser's body, military life was even tougher. One day, after a long march in below-zero weather, he started feeling woozy and was diagnosed with pneumonia. Doctors were ready to issue a medical discharge when the base commander realized he had the great Pete Reiser in the infirmary. He kept him at Fort Riley so he could play for the camp team after he recuperated. Pete was excused from all duties, could leave the base virtually whenever he liked, and had his own private room. Even on an army team, Reiser was incapable of letting up. Once, he was chasing a fly ball and burrowed right through the thick hedge that formed the outfield wall and down a ten-foot drainage ditch. He separated his shoulder and couldn't throw. So he simply threw with his left arm, as he had in 1939. When the war ended, he was almost sent to Japan as part of a team that would play exhibitions to entertain the troops. Luckily for him, a base doctor looked at his medical records and was appalled. Clearly, he never should have been allowed into the army in the first place. Pete was discharged charged early in 1946, in time to catch up with the Dodgers in spring training. The Brooklyn brass noticed right away that their former star no longer had a Major League arm. Previously, there had been discussions within the organization that he might be better off in the infield, if only from a self-preservation standpoint. But now that was out of the question. Pete's season ended early with a fractured fibula suffered during a stolen base attempt. Prior to that he had reinjured his shoulder and limped through a series of minor pulls, sprains, and strains. The shoulder got so bad that he was moved to left field, and he often threw the ball underhand. In an August game with the Cardinals, he ran into the left-field wall chasing a hit. While convalescing at home, he burned his hands lighting the oven for his wife. It just wasn't Pete's year. Even so, Reiser could still run. He led the league in 1946 with 34 stolen bases-including seven steals of home. He batted .277 in 122 games and led the team with eleven home runs, three of which were inside-the-park. By the time he hurt his ankle, however, his swing had become hitched and choppy because of the aching shoulder. He was basically a slap hitter in the second half.  Augut 14, 1946: Reiser slides into home ahead of the tag by Giants C Walker Cooper on the front end of a triple steal. That gave Pete a new National League record with his sixth steal of home. The ill effects of the head injury - plus a sore leg - were evident in the World Series against the Yankees. Reiser misplayed a couple of balls in the first two games. He started Game Three but injured his ankle on a steal attempt. Manager Burt Shotton replaced him, and Pete spent the remainder of the Series as a bench player. Reiser was never a regular player again. In 1948 Durocher returned to the Brooklyn dugout from his one-year suspension and saw that Pete was no longer capable of playing the outfield. Durocher believed that he could at least keep the potent Reiser bat in the lineup. So Pete was a candidate for the first-base job-until Leo saw him in action and realized that he needed to look elsewhere. Pistol Pete had gained a few pounds and was sluggish around the bag. Reiser saw sporadic playing time at third base for a few games. Mostly he was used as a pinch hitter and fill-in outfielder. He spent much of the 1948 season on the injured list and finished with a .236 average in 64 games. After the season, Pete asked Rickey to trade him. Rickey obliged, engineering a swap with the Boston Braves. Though still no more than a bench player, Reiser enjoyed a minor renaissance in Boston in 1949. He saw action in the outfield and at third and collected 19 extra-base hits among his total of 60. He batted .271. Pete's 1950 campaign was a different story. His average sank to .205. The Braves released him after the season. Less than a week after leaving the Braves, Rickey, now running the Pirates, acquired Reiser for the third time. He proved to be a handy bench player, hitting .271 in 74 games. Rickey released him after the season but offered him a chance to manage the Pirates' farm club in New Orleans. But Pete felt he had some more good baseball in him. He was signed by the Cleveland Indians. He functioned primarily as a pinch hitter in 1952, playing just ten games in the outfield. He batted a paltry .136 with three homers in the first half and played his final game as a Major Leaguer on July 5. The injury that ended his career was a separated shoulder, suffered while sliding. When Pete told Manager Al Lopez that he was retiring, Lopez cried. Like everyone eryone who had seen Pete in his prime, he was saddened that a good guy and great player had suffered such relentlessly horrible luck. Pete worked for the Dodgers as a minor league hitting coach and also worked with Maury Wills on his base stealing to transform Wills into the league's top base stealer whose 104 steals in 1962 broke Ty Cobb's record. Reiser would later tutor Sandy Alomar on base steaing. Pete also managed in the minor leagues and coached for Durocher when Leo became skipper of the Cubs. Catching Up: Ted Simmons

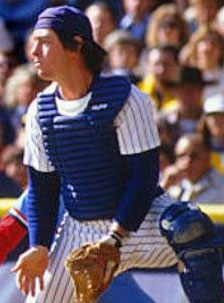

His journey to Cooperstown has given him an unbreakable passion for the game.

Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the Hall of Fame by Rick Hummel

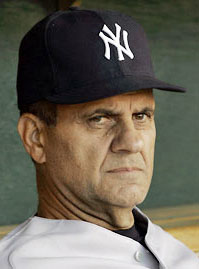

Winning Record: Derek Jeter

Derek Jeter's talent, tenacity brought the Yankees back to the top.

Memories and Dreams: The Official Magazine of the Hall of Fame by Tyler Kepner

|