|

Baseball Profile

Gil Hodges

"Humble Hero," Memories and Dreams: Official Magazine of the Baseball Hall of Fame,

Spring 2022 by Wayne Coffey A half-century after his tragically premature death as the start of the 1972 season approached, Gil Hodges will be enshrined in the Hall of Fame this summer, having been elected by the Golden Days Era Committee. In the minds of many baseball fans, Hodges' election—on his 35th time on the ballot—was long overdue.

The Hall of Fame teems with transcendent talents and baseball icons, of course, but one would be hard-pressed to find a member more revered—as a player, manager, and person—than Gilbert Raymond Hodges, who won a Bronze Star as a Marine serving in Okinawa in World War II before becoming a beloved Brooklyn Dodgers, starring at bat and in the field.

An eight-time All-Star and two-time World Series champion, Hodges, at 6-foot-1, 200 pounds, topped the 20-home run mark for 11 consecutive seasons. He drove in 100 or more runs each year from 1949 through 1955, the latter season marking Brooklyn's only title.

On Aug. 31, 1950, Hodges became only the fourth player in baseball's modern era to hit four home runs in a game. The first was Lou Gehrig in 1932. When reporters asked Hodges to compare himself to his fellow New York first baseman, he humbly replied, "The only difference between us is he's a much better player."

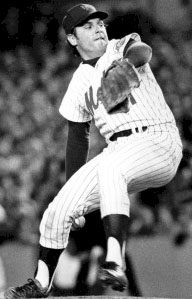

L-R: Gil Hodges as player and manager, Tom Seaver, Vince Scully Hodges, the son of an Indiana coal miner, also was a brilliant fielder, renowned for his deft hands and his ability to charge bunts. The sole reason he won only three Gold Glove Awards is the honor didn't start until near the end of his career.

Despite his success on the field, many doubted whether Hodges would be a good manager, questioning if he would be able to assert authority and be tough on players when needed. They quickly found out he could do the job. Hodges wrapped up his playing career with the expansion Mets in 1962 and early 1963, before being traded to the woeful Washington Senators six weeks into the '63 season so he could take over as their manager. The Senators were a last-place team he methodically shepherded up to sixth place in four-plus seasons.

Hodges' body of work was enough to persuade Mets executive Johnny Murphy to make the bold—and almost unprecedented—move of sending $100,000 and a player (promising pither Bill Denehy) to the Senators in exchange for their manager.

So in 1968, Hodges came home to New York. The Mets had been historically awful from their inception, but the club's culture—and its professionalism—changed the moment Hodges walked through the door. He wasn't big on hollering or theatrics or team meetings, but his authority was unquestioned.

"He could give you a look that would singe your shorts," Mets ace Tom Seaver once said.

To a man, the '69 Mets believe they never would have won the World Series without Hodges.

Not even two-and-a-half years later, Hodges suffered a fatal heart attack on Easter Sunday 1972, two days before his 48th birthday.

On the December 2021 night of the Golden Days Era Committee election, 96-year-old Joan Hodges got the call from Jane Forbes Clark, chairman of the board of the Hall of Fame. The Hodges' daughter Irene hadn't told her mother about the balloting because she didn't want her to be disappointed if it didn't happen.

"Daddy's in the Hall of Fame," Irene told her mother.

"What, my Gil?" Joan responded.

Shortly after, Vin Scully, the legendary Dodgers broadcaster who probably saw Hodges play more games than anyone, called to congratulate Joan on the happy news. Scully was among those who wrote to the Golden Days Era Committee on Hodges' behalf, stating that Hodges was in a class by himself, "in terms of the players I watched who performed at a high level on the playing field, but at an even higher level off the field in how they lived and carried out their lives."

|