|

Pivotal World Series Moments

More Suspicious Cub Shenanigans

1918 World Series - Game 4: Chicago Cubs @ Boston Red Sox

As the Cubs and Red Sox boarded trains in Chicago after Game 3 for the trip to Boston for the remaining games of the Series, three outside forces were influencing the players' attitudes toward the competition.

The players, team personnel, and reporters were unknowingly headed to the epicenter of the burgeoning "Spanish Flu" epidemic. The day of Game 3, 200 sailors at Commonwealth Pier in East Boston were reported to be suffering from the flu after serving in Europe. During the travel day, another 30 ill sailors were transferred from training ships to a hospital in Brookline MA.

The second development was related to the first. Both teams had been given extensions of the "Work or Fight" order of the Secretary of Defense until the end of the Series. So the players faced the prospect of no longer being able to collect a good salary while hiding from the war.

The other factor involved the money to be paid the players participating in the Series. The previous winter, the National Commission that governed baseball had set the player shares at $2,000 for the winners and $1,400 for the losers. Or so the Cubs and Red Sox thought. Notices were slid under their hotel room doors before Game 1 that they were entitled to 55.5% of the gate receipts for the first four games of the Series.

But there were three problems–one small, two large–with the 55.5% figure. First, 10% of the 55.5% would be deducted as a war charity donation. More significantly, interest in the 1918 World Series was significantly diminished from 1917. Before they played the Giants, the White Sox turned away 300,000 requests for reserved seats even with the Commission jacking up the prices for tickets for the Fall Classic. 64,000 attended the first two games at Comiskey Park in 1917. And another 33,616 came to the Polo Grounds in New York for Game 3. In contrast, only 66,368 attended the three games in Chicago in 1918. To make matters worse for the players, the Commission also decided to charge the regular season prices for the wartime World Series.

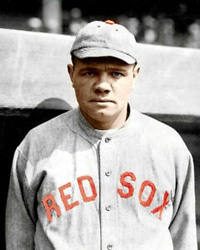

L-R: Les Mann, Garry Herrmann, Babe Ruth Attendance may have waned, but betting was still rampant. According to a story in the Boston Post, eight times as much money had been bet on the Cubs than on the Red Sox. So anyone taking Boston could get odds from 10 to 8 down to 6 to 5.

After arriving in Boston for Game 4, outfielder Les Mann, the Cubs player representative, phoned Garry Herrmann, chairman of the three-man National Commission, and told him that the players wanted the $2,000 for the winners and $1,400 for the losers that they'd been promised. If they could not be guaranteed those amounts, the teams would not play Game 4. Using the fact that Ban Johnson, the American League representative on the Commission, would not get to Boston until shortly before game time, Hermann informed Mann that any decision would have to wait until after Game 4. Furthermore, Garry claimed (falsely) that the commission needed a unanimous vote of all 16 team owners to make the change. Mann and the players agreed to play Game 4 with the understanding that they would meet with the commission later.

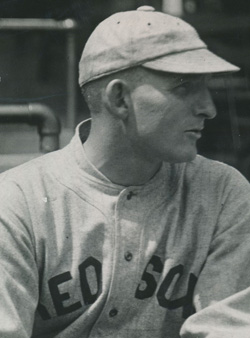

L-R: Max Flack, Charlie Hollocher, Sam Agnew Babe Ruth, who shut out the Cubs four days earlier, took the mound to a big ovation with a streak of 22 consecutive scoreless World Series innings. What only a few people knew was that Babe was pitching with a sore finger on his left hand suffered during a playful scuffle with a friend.

Peculiar play started immediately. RF Max Flack, who had been beaned by Ruth in Game 1, smacked a single to right field. After SS Charley Hollocher lined out, LF Mann came to the plate. Flack took a big lead off first and "just seemed to stop paying attention." C Sam Agnew took the next pitch from Ruth and threw to Stuffy McInnis at first to pick off Flack.

Two innings later, Flack reached first again, this time on a forceout. He then took second on a grounder to first. He again took a big lead and started kicking at the dirt instead of paying attention to the game. Ruth turned and fired to second to pick off Flack for the second time. Flack still holds the dubious distinction of being the only player to be picked

off twice in the same World Series game.

Flack still wasn't finished his shenanigans. With the score 0-0 in the bottom of the 4th, Ruth came to the plate with runners on first and second and two out. P Lefty Tyler pitched carefully to Babe to run the count to 3-2. Then Lefty stepped off the mound and looked out to right field and wondered why Flack was playing so shallow against the best left-hand hitter in the game. As the Boston Herald Examiner reported the next day, "Flack was in too close. Tyler waved him back. Flack did not pay attention to the command. Once again Tyler motioned him, but Max obstinate." Ruth crushed the next pitch into right. Flack inexplicably took a step in before turning to chase after the ball, which sailed far over his head and rolled to the fence. Both runners scored, and Ruth ended up on third.

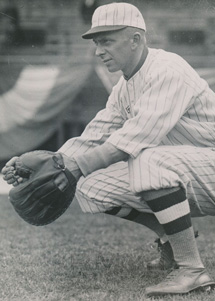

L-R: Stuffy McInnis, Lefty Tyler, Bill Killefer, Claude Hendrix Babe wasn't at his best, but he preserved the 2-0 lead into the 8th. He issued a free pass, his fifth of the game, to the leadoff batter, C Bill Killefer. Cubs manager Fred Mitchell chose Claude Hendrix, a good-hitting pitcher, to bat for Tyler. Hendrix singled, Killefer stopping at second. That brought Flack to the plate. Ruth unleashed a wild pitch to advance the runners to second and third. Hendrix proceeded to take a wide lead off second and was almost picked off. Mitchell, having seen enough bad base running for one game, sent out Bill McCabe to run for Hendrix. Two men on, no outs, Ruth tiring. "Here was a fine chance for Max Flack to redeem himself," reported the New York Times. But Max sent an easy grounder to first, the runners holding. But the Cubs tied the game any way with another ground out and a single.

The Red Sox retook the lead in the bottom of the 8th with the help of some more Cub shenanigans. Douglas, a spitballer, stayed in the game as the pitcher. PH Wally Schang singled. With RF Harry Hooper at the plate, Douglas uncorked a pitch that got past the catcher to send Schang to second. Hooper then laid down a bunt. Douglas came off the mound, picked up the ball, and threw it far over the head of 1B Fred Merkle. The runner came all the way home with the go-ahead run.

When Merkle singled and 3B Rollie Zeider walked in the top of the 9th, Boston manager Ed Barrow brought in Bullet Joe Bush, who got a forceout and a game-ending double play to put the Sox up three games to one in the Series.

Chicago White Sox P Eddie Cicotte filed a court deposition in 1920 during the Grand Jury's investigation of the 1919 World Series stating that he and his fellow conspirators talked about how one or more Cubs were offered $10,000 to throw the 1918 Series.

|