|

Pivotal World Series Moments

A's Play It Straight to Finish Off Giants

1913 World Series Game 5: Philadelphia Athletics @ New York Giants

The A's won three of the first four games against the Giants in a Series that alternated games between the two cities. A's manager Connie Mack really wanted to win Game 5. In an article in the Saturday Evening Post titled "Honesty in Baseball," he explained:

This brings me ... to the last game of the World Series that was played in New York on Saturday. There were many reasons why I wanted this game, wanted it badly. One of these, and not the least important reason, was that I knew the gamblers expected us to lose. When the Series opened, we sold tickets for three games in Philadelphia, with the understanding were betting on what they thought was a certainty. You see, if the third game were not played, the money would be refunded. ... Everybody knew approximately how much money was at stake. With the exception of the bleachers every seat in Shibe Park had been sold for Monday's game, and the money was actually in the treasury of the club. The amount, to give the exact figure, was $45,639. Looking at it from a commercial angle–from the dishonest standpoint–there was every inducement for our club-not the players-to lose Saturday's game. We won the game, 3-1. We paid back in cash to holders of tickets $45,639. Compare this with any business you know intimately and then tell me if you find any evidence of downright dishonesty ...   John McGraw and Connie Mack Esteemed baseball writer Leonard Koppett wrote this about the contrast between the two managers.

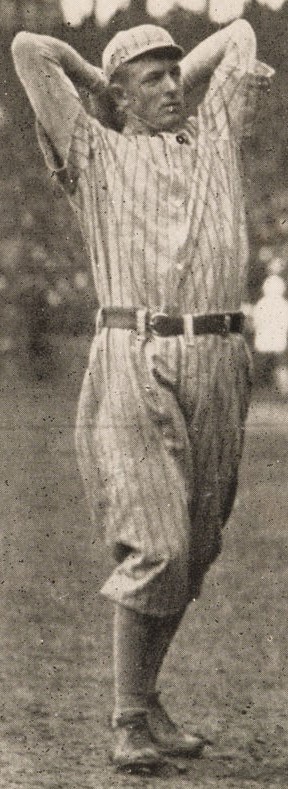

Connie Mack was the complete opposite of John McGraw. That's the way the public saw it, and the public was right. Game 5 was a battle of the two aces, A's southpaw Eddie Plank and the incomparable Christy Mathewson of the Giants. Both pitched well, allowing only eight hits between them with the home team managing only two off Plank.

Philadelphia 3B Frank "Home Run" Baker had become Giants' Enemy #1 during the 1911 World Series when he won two games with home runs, one of which came off Mathewson. That feat made the entire country aware of the nickname "Home Run" he had received in spring training of his rookie season in 1908.

Baker continued to plague the Giants and Mathewson in Game 5 in 1913. He drove in two of the Athletics' three runs with a first-inning sacrifice fly and a single in the third inning.

L-R: Eddie Plank, Christy Mathewson, Frank Baker Reference: The Man in the Dugout: Baseball's Top Managers and How They Got That Way, Leonard Koppett (1993)

|