This series covers the history of the NFL through the prism of its yearly championship games.

Note: The gray boxes contain asides that provide interesting material

but could be skipped without losing the continuity of the article.

Note: The gray boxes contain asides that provide interesting material

but could be skipped without losing the continuity of the article.

George Preston Marshall, second year owner of the Boston Redskins National Football League team, had an idea for his fellow owners in the summer of 1933. The league would split into two divisions. The winners of the divisions would play for the championship just as baseball's National and American League pennant holders met annually in the World Series. With the Great Depression raging, the owners welcomed any idea that might increase interest and put more fannies in the seats. So they set up the divisions like this.

| Eastern Division | Western Division |

|---|---|

| Boston Redskins | Chicago Bears |

| Brooklyn Dodgers | Chicago Cardinals |

| New York Giants | Cincinnati Reds* |

| Philadelphia Eagles* | Green Bay Packers |

| Pittsburgh Pirates* | Portsmouth Spartans |

The league made another key decision: To stop using the same rules as the colleges and develop its own brand of football that would be more entertaining for the fans. So these modifications were adopted for 1933.

- The forward pass was made legal anywhere behind the line of scrimmage. Previously, the passer had to be at least 5y from the line of scrimmage. The intent of the change was to increase scoring.

- Hashmarks were added to the field 10y from each sideline. All plays would start with the ball on or between the hashmarks. Previously when the ball carrier was tackled close to the sideline or knocked out of bounds, the ball would be placed at the point of the tackle or the out of bounds spot. This forced team to waste a down moving the ball closer to the center of the field laterally to gain maneuvering room for the next snap.

- In another move to increase scoring and cut down on tie games, the goal posts were moved from the back of the end zones to the goal lines.

- To cut down on injuries, the penalty for clipping was increased from 15 to 25y.

The 1933 NFL officiating crew consisted of four men: referee, umpire, head linesman, and field judge–this last position added in 1929 as the passing game developed.

- Only the referee had a whistle.

- There were no penalty flags. When an official spotted a foul, he blew a small horn worn around his wrist.

- Hand signals, invented by a college referee in the late '20s, informed spectators of infractions. Most of the signals were the ones we're all familiar with today. The exception was the sign for unnecessary roughness, which was a military salute until 1955.

- Either the field judge or the umpire would keep time. Two minutes before the end of each half, play was stopped so that the referee could inform each coach of time remaining–a habit that continues to this day not out of necessity but to provide an extra commercial break.

- Officials were hired and paid by the home team ($25 apiece). This system was ripe for abuse and intimidation.

- The refs wore white trousers, white shirt, black bow tie, and preferably black stockings. (You can see an official in a picture further down this page.) It wasn't until 1935 that officials wore black and white shirts after teams complained that the white shirts caused confusion amid the white shirts of one of the teams in each game.

The rules changes had the desired effect.

- The number of ties dropped from 10 to five.

- The average points per game rose from 16.2 in 1932 to 18.9–almost a field goal more per contest.

- Unfortunately, the progress in providing a more interesting product was accompanied by a step backward in another aspect. For the first time in league history, there was not a single African-American on any roster. The NFL would remain segregated until 1946.

L: Bears RB Bronko Nagurski, whom Mel Hein thought was the best player in football;

R: Giants C Mel Hein, whom Nagurski considered the best defensive player in the NFL.

1933 Chicago Bears

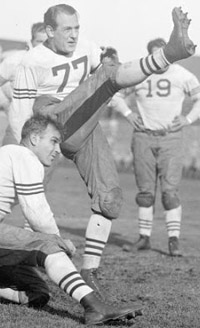

Back (L-R): George Halas (11), Bert Pearson (26), Ookie Miller (76), Bill Karr (22), Paul Franklin (9), Bronko Nagurski (3), Joe Zeller (17), George Musso (16), Ray Richards (44), Roy Lyman (12), Cliff Battles (29) & Frank Halas. Front (L-R): Laurie Walquist, Eddie Kawal (19), John Doehring (27), Johnny Sisk (7), Carl Brumbaugh (8), George Corbett (5), Red Grange (77), Gene Ronzani (6), Jack Manders (10), Bill Hewitt (56) and Jules Carlson (20)

The Chicago Bears adapted to the new rules quickly, winning their first six games.

- George Halas, one of the founders of the NFL, bought out his co-owner and reinstated himself as the coach for the first time since 1929.

- The Bears boasted an array of top players led by the one and only Bronko Nagurski. The 25-year old 6-2 226 lb FB from Minnesota easily led the club with 533y rushing, which ranked him third in the league behind Jim Musick (809) and Cliff Battles (737), both of Boston.

Steve Owen, the Giants' coach and right tackle, offered the best advice for dealing with Nagurski.

"How will you stop Nagurski?" someone asked Steve.

He replied, "With a shotgun as he comes out of the dressing room."

"How will you stop Nagurski?" someone asked Steve.

He replied, "With a shotgun as he comes out of the dressing room."

Owen's star C-LB Mel Hein explained his approach to tackling Bronko: "I learned that if you hit him by yourself, you were in trouble. If you hit him low, he'd trample you to death; if you hit him high, he'd take you about 10 yards. The best way to tackle Bronko was to have your teammates hit him about the same time - one or two low, one or two high. He was the most powerful fullback that I ever played against ... Bronko had a knack of running fairly low. He had a big body and he could get that body, that trunk, down and be able to throw his shoulder into you. If you didn't get under his shoulder, he just knocked you butt over tea kettles."

The most famous Bear, however, was Red Grange, the "Galloping Ghost" who had electrified the football world at Illinois. But a severe knee injury in his first year of pro football had cut Red's speed and limited him to spot duty on defense.

Grange later recalled: "After that injury [in 1927], I came back, but I could never do again what I'd been able to before. I was just an ordinary back after that, the moves were gone forever. I wore a brace with steel hinges on both sides. The injury not only slowed me down, but I couldn't make the turn anymore. In other words, I became a straight runner ... I guess I was about seventy percent of the football player I'd been but I worked on playing defense and that became a strong point with me." Halas called Red "the game's greatest runner until he hurt his knee and after that the game's best defensive back." The Bears ran an early version of the T-formation with a man in motion on many plays. Solid on both sides of the ball, they won the Western Division easily with a 10-2-1 record. |

Red Grange kicking |

The Giants won the East title in a cakewalk also, finishing 11-3.

- The New Yorkers were led by Hein, who was joined at linebacker on defense by FB Bo Molenda.

- The backfield of Harry Newman, Ken Strong, Dale Burnett, and Molenda ran the traditional single wing expertly. Newman, the rookie All-American tailback from Michigan, led the league in passing yards with 973, 199 more than Glen Presnell of Portsmouth.

- The division champs had met twice during the season, the Bears winning in Chicago 14-10 on October 29 and the Giants prevailing at the Polo Grounds 7-3 November 19.

The owners needed their first title game to create a buzz, and they weren't disappointed as the undisputed kings of the league clashed at Wrigley Field in Chicago on December 17.

- They also needed reasonably good weather unlike the year before when the Bears (6-1-6) and Portsmouth (OH) Spartans (6-1-4) tied for first place and met in a playoff. The teams had tied both times they faced each other in the regular season, thereby nullifying the league's only tie-breaker and providing motivation for rules changes for the following season to reduce the number of deadlocks.

- However, sub-zero wind chill weather forced the game indoors to Chicago Stadium where the Chicago Black Hawks hockey team played. The arena floor wasn't big enough for a regulation football field. So the teams cavorted on a surface that measured only 80y long, including the end zones, and was 10y narrower than the regulation width.

- Two accommodations for the reduced field gave fans a foretaste of new rules for 1933. The goal posts were moved to the goal lines, and, since the sidelines butted up against the stands, all plays started with the ball on or between the hash marks 10y from the sidelines.

- Because of the reduced field length, the ball was moved back to the 20y line the first time a team crossed midfield on an offensive possession.

- The excitement generated by the playoff inspired Marshall to propose the two-division setup with its guaranteed championship game and helped him persuade the owners to accept the idea.

Pictures from the 1932 Bears-Spartans championship game played indoors

The Associated Press article the day of the 1933 title game explained pro football to a nation that favored baseball, boxing, horse racing, and college football. The writer also made some uncanny predictions about the action.

"The New York Giants go into another world series tomorrow. [The baseball Giants won the '33 World Series over the Washington Senators.] This time it's football. ... Missing from the spectacle will be the parading bands, the college cheering sections and the campus atmosphere, but there will be tough thrilling runs and forward passing to make up for it. ... The game will be desperately fought, as the players will be fighting for 60 per cent of the receipts, with 60 per cent of this pool going to the victors and 40 per cent to the losers. Under the league regulations the receipts of the game will be divided three ways, 60 per cent going" to the player pool, 15 per cent to each club and the remaining 10 per cent to the league. "

"The New York Giants go into another world series tomorrow. [The baseball Giants won the '33 World Series over the Washington Senators.] This time it's football. ... Missing from the spectacle will be the parading bands, the college cheering sections and the campus atmosphere, but there will be tough thrilling runs and forward passing to make up for it. ... The game will be desperately fought, as the players will be fighting for 60 per cent of the receipts, with 60 per cent of this pool going to the victors and 40 per cent to the losers. Under the league regulations the receipts of the game will be divided three ways, 60 per cent going" to the player pool, 15 per cent to each club and the remaining 10 per cent to the league. "

The weather cooperated to a degree.

- The high was 42° and the low 28°.

- A light rain fell in the first half with mist and fog hanging over the gridiron as the game began.

- The field was slippery, especially in the grassy spots.

Nevertheless, the crowd estimated at 26,000–the largest since Grange's rookie year–saw a scintillating game that produced pro football at its best.

- Players from each team met separately with the officials before the game. Each side planned to pull a trick play and wanted to alert the officials so they wouldn't call it illegal.

- The Giants moved well on their first possession, all the way to the 15, before running out of gas.

- From The First Fifty Years: The Story of the National Football League:

One of the game's stranger incidents was a center-eligible almost-pass in the first quarter. As Giant C Hein remembers it: "This was a play we had to alert the officials about ahead of time. We put all the linemen to my right except the left end. Then he shifted back a yard, making me end man on the line, while the wingback moved up on the line on the right. Harry Newman came right up under me, like a T-formation quarterback. I handed the ball to him between my legs and he immediately put it right back in my hands–the shortest forward pass on record. I was supposed to fake a block and then just stroll down the field waiting for blockers, but after a few yards I got excited and started to run and the Bear safety, Keith Molesworth, saw me and knocked me down. I was about 15y from the goal, but we never did score on that drive.

When Bears' DT George Musso tackled Newman, he bellowed, "Where the hell's the ball?" Some accounts say Hein hid the ball under his shirt.

Shortly afterwards, Bears QB Keith Molesworth quick-kicked over Newman's head, Strong returning the punt to the Giant 42.

|

Jack Manders |

The Bears regained the lead early in the second half.

- Repeating their pattern from the first half, Chicago moved the ball but bogged down in enemy territory. Ronzani gained 15, then Molesworth hit QB Carl Brumbaugh to the 13. Four snaps later, Manders kicked a 28y field goal for a 9-7 lead.

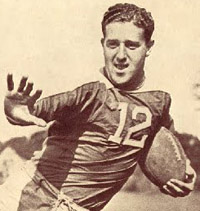

- Newman retaliated by shredding the Chicago D "in a sensational display of passing" to move briskly 61y. Hurling Harry connected with Burnett, Richards, and blocking back Max Krause, the last completion out of bounds at the 1. Krause plunged over from there, and Strong's PAT made it 14-9.

- Knowing they couldn't keep trading field goals for touchdowns, the Bears gambled. Facing a third-and-long, Chicago went into punt formation. But instead of kicking, HB George Corbett threw to Brumbaugh for a 67y gain to the 8.

- Then they seemed to go back to an old formula, sending Nagurski straight ahead. But that's when Halas's men capitalized on another of Marshall's rule changes. On second down, with the Giants braced for another dose of Nagurski, Bronk suddenly jumped and flipped an end-over-end basketball pass to RE Billy Karr in the end zone. The play would have been illegal in 1932 when the passer had to be more than 5y behind the line of scrimmage. Manders' conversion made it 16-14.

Nagurski had done the same trick in the 1932 playoff against Portsmouth, tossing to Grange for the only touchdown in the Bears' 9-0 win. To their dying days, every Spartan player swore that the pass was illegal because Bronk was less than 5y from the line of scrimmage.

The exhilaration of finally scoring a touchdown didn't last long for the Bears and their fans as the Giants came right back.

- Mixing Newman's passes with Strong's runs, the Giants started a march from their 26 that carried into the final period. When they reached the eight, they pulled some trickery of their own. Let Strong recount the unplanned flea flicker that happened next.

- Ken's conversion made it 21-16.

Newman handed off to me on a reverse to the left, but the line was jammed up. I turned and saw Newman standing there, so I threw him the ball. He was quite surprised. He took off to his right, but then he got bottled up. By now I had crossed into the end zone and the Bears had forgotten me. Newman saw me wildly waving my hands and threw me the ball. I caught it and fell into the first-base dugout. [The Giants later put this play in their offense, but it never worked again.]

The Giants forced a punt on the Bears' next possession.

|

Dale Burnett |

But no one should have expected the Giants to go down without a fight.

- On the first snap after the kickoff, they lined up as they had earlier on Hein's hidden-ball play. However, this time Newman pitched out to Burnett. As the Bears chased him, Hein went downfield as a receiver, but swarming Bears knocked down Dale's pass.

- On the final snap, Newman threw to Burnett in the open field, but Grange made a game-saving play, as Red recalled. "I was alone in the defense and Burnett was coming at me with somebody on the side of him [Hein]. I could see he wanted to lateral, so I didn't go low. I hit him around the ball and pinned his arms. I never did throw him."

The NFL couldn't have asked for a better inaugural title game. The game illustrated how much more exciting football could be under the new rules. As the AP report put it: "The struggle was a revelation to college coaches who advocate no changes in the rules. It was strictly an offensive battle and the professional rule of allowing passes to be thrown from any point behind the line of scrimmage was responsible for most of the thrills."

To illustrate the status of pro football at the time, the New York Times didn't bother to send one of its own correspondents to cover the game, instead running the AP wire report.

- As an example of how evenly matched the contestants were, the Bears gained 311y to 307 for NY. Chicago gained most of its yardage on the ground - 161 to 99 - while the Giants did more damage through the air - 208 to 150. The visitors had the edge in first downs by just one, 13 to 12.

- Nagurski led the rushers with 65 hard-earned yards on 14 carries while Newman hit 12-of-17 for 201y and two touchdowns.

- Each member of the Bears' 20-man roster received $210 each while the losers took home $140 each. At a time when the star players made anywhere from $3,600 to $6,000 per season, a few hundred extra bucks increased the average player's earnings substantially.

- So the Bears gathered at the Cottage Lounge on the North Side of Chicago to celebrate their triumph that afternoon.

- Assistant coach George Trafton, former star T for Halas, offered the first toast of the evening. "Once again a toast to the Ghost. But, Nagurski, you're still the man with the most."

References

Championship: The NFL Title Games plus Super Bowl, Jerry Izenberg (1970)

The Chicago Bears, Howard Roberts (1947); The First Fifty Years, NFL Properties, Inc. (1969)

What a Game They Played: An Inside Look at the Golden Era of Pro Football, Richard Whittingham (1984)

NFL Top 40: The Greatest Pro Football Games of All Time, Shelby Strother (1988)

The 50 Greatest Plays in New York Giants Football History, John Maxymuk (2010)

Monster of the Midway, Jim Dent (2003)

Top of Page

Championship: The NFL Title Games plus Super Bowl, Jerry Izenberg (1970)

The Chicago Bears, Howard Roberts (1947); The First Fifty Years, NFL Properties, Inc. (1969)

What a Game They Played: An Inside Look at the Golden Era of Pro Football, Richard Whittingham (1984)

NFL Top 40: The Greatest Pro Football Games of All Time, Shelby Strother (1988)

The 50 Greatest Plays in New York Giants Football History, John Maxymuk (2010)

Monster of the Midway, Jim Dent (2003)

Top of Page