|

Red Grange Turns Pro - 1

The Red Grange Story: An Autobiography, as told to Ira Morton (1953)

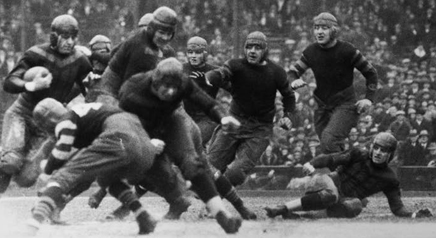

There were many who thought I made a big mistake when I turned pro after my last college game in the late fall of 1925. Professional football in those days was frowned upon by faculty representatives, coaches, athletic directors and the commissioner of athletics for the Big Ten Conference. It was hard to find anyone in college circles for it. ...

Of course, time has changed all that. Today pro football occupies the same high position in the sports world as college football. ... Naturally it was impossible back in 1925 for me or anyone else ... to foresee all the changes that have taken place. Yet if I were placed in the same position today as I was then, I would still follow the identical course. I wish to make the point strong that I have never for one instant regretted what I did. The story behind my turning professional and my association with Charlie Pyle, who was responsible for the whole thing, begins the second week of my senior year at Illinois. I was about to take my seat in a Champaign movie house one Saturday night when an usher approached me. Handing me a slip of paper with a few words scribbled on it he said, "Mr. Pyle who runs this theater wants you to have this. It's a pass that'll get you in the Virginia Theater as often s you want for the rest of the year ..." Several days later I went to the Virginia again. As I entered the theater I was greeted in the lobby by Mr. Pyle and invited up to his office. I had heard his name mentioned many times before, but never met him. ... "How would you like to make one hundred thousand dollars, or maybe even a million?" Pyle asked. I was momentarily stunned. Regaining my composure, I quickly answered the query in the affirmative. When I attempted to find out what Pyle had in mind he told me he had a plan, but wasn't at liberty to reveal the details at the time. He said he'd contact me in a few weeks and made me promise that after leaving his office I wouldn't mention our conversation to anyone. I found out later that Pyle left the next day for Chicago to confer with George Halas and Ed Sternaman, co-owners of the Chicago Bears. He offered them a tentative deal whereby I would join their team immediately after my last college game against Ohio State. I was to play in the remaining league games that season and then go on tour with the Bears in a series of exhibition games that Pyle would book himself from Florida to the West Coast. According to Pyle's proposition, the Bears were to share the gate receipts approximately fifty-fifty with us. This Pyle intended to split sixty-forty in my favor. At first, Halas and Sternaman balked at the percentage figures, but ... finally agreed to terms. Pyle then left Chicago to book the exhibition games in the West and Far South.   L-R: Red Grange and Bob Zuppke During my senior year rumors were continually circulating about the possibility of my becoming a professional. ... No one other than Pyle ever approached me while I was at Illinois and we kept our plans with Halas and Sternaman secret until after the Ohio State game. One week before the battle in Columbus, the Champaign News-Gazette called me into their office and practically accused me of having signed a contract to play pro ball. They told me I wasn't eligible to play against the Buckeyes because of it. I replied that I had not affixed my signature to any contract and defied them to produce evidence to the contrary. ... Two days before the Buckeye-Illinois battle there was a report that L. W. St. John, the Ohio State athletics director, might challenge my eligibility to play against his team because of the rumors that I had inked a professional contract. St. John answered the report with: "If Red Grange denies the rumor, his word is good enough for me." ... The contest with the Buckeyes was played on November 21st before a packed house of 85,500, the largest crowd ever assembled anywhere up to that time for a football contest. ... We defeated Ohio State 14-9. As the gun went off, ending the game, reporters swarmed about and pressed me for a statement. I announced for the first time my intention to play with the Chicago Bears and informed them I was going to sign a contract in Chicago the following day. Zup [Illinois coach Bob Zuppke], visibly disturbed by the news, drove with me from the stadium to the hotel. ... we spent almost an hour in a cab as Zup ordered the driver to "keep driving" while he tried desperately to make me change my mind. ... "Football isn't a game to play for money." My reply summed up what I believed all along. "You get paid for coaching, Zup, why should it be wrong for me to get paid for playing?" We finally parted and I didn't see Zup again for about three weeks. By then I had played in several pro games. We were attending the annual Elks banquet in Champaign for the Illinois team and Zup was the principal speaker. During the course of his speech he berated me for joining the pro ranks. I thought his remarks were completely uncalled for. ... I was so mad at Zup at the time I got up from my place at the speaker's table and left the hall while he was still talking. The next day we had both forgotten the incident. To be continued ... Red Grange Turns Pro - 2

The Red Grange Story: An Autobiography, as told to Ira Morton (1953)

I made my pro debut in Chicago against the Chicago Cardinals on Thanksgiving Day, November 26, 1925. Thanks to a tremendous barrage of publicity that accompanied my joining the pro ranks, 36,000 fans crowded into Wrigley Field to watch the game. It was the largest turnout ever recorded up to that time for a pro game. ... I entered the Bears-Cardinals contest under a handicap. I had only three days' practice prior to the game and didn't know too many of the Bears' signals. Coaches Halas and Sternaman employed a "T" formation and although it was vastly different from what we know today as the "T," it was still an adjustment for me to make from the single wing Zuppke used at Illinois. I made 92y against the Red Birds that day but wasn't able to get away for a touchdown. My longest gains came on punt returns. On defense I intercepted a pass ... As was expected, the Bears-Cardinals clash was hard fought and finally wound up in a 0-0 tie. The customers left the park somewhat disappointed that I was unable to scamper for a touchdown, but satisfied they saw a good football game. On Sunday, three days after the clash with the Cardinals, we played an encore at the Cubs' ball park. This time we faced the Columbus Tigers. Thanks again to the wonderful support we got from the newspapers, 28,000 defied a snowstorm to watch us nose out the Tigers 14-13. As in the Cardinals game, I was unable to cross the goal line but succeeded in plowing 140y through the snow in the thirty minutes I played. I threw two completed passes, one that went ... for a net gain of 32y and a tally. The following Wednesday, December 2nd, the Bears played an exhibition game against a hurriedly recruited eleven called the Donnelly Stars in Sportsman's Park, St. Louis. The weather was so cold only about 8,000 were to hand to witness the one-sided battle. We romped over them 39-6 and I accounted for four of the touchdowns. ... We boarded a train for Philadelphia immediately after the game since we were due, on Saturday, to meet the Frankfort Yellowjackets in Shibe Park. It had rained heavily in Philly the night before [causing] muddy playing conditions. Before 40,000 rain-soaked fans, the Bears beat the Yellowjackets 14-0. I proved to be a good mud horse again by scoring both touchdowns. ... On December 6th, the next day, we took on the New York Giants in the Polo Grounds. The New York papers gave the game such a big build-up lines started forming outside the stadium in the morning. When kickoff time arrived, we had a packed house of 65,000. At the half we were leading 12-7 ... In those first two periods my contribution consisted of receiving a pass ... for 22y and throwing a pass ... for 23 more. In the third period neither team scored. But in the last quarter I intercepted a pass ... and ran it down the side lines 30y for a touchdown. The game ended with the Bears on the long end of a 19-7 victory. The Bears took a terrific physical beating against New York. Although we had won, it was one of the most bruising battles I had ever been in. I especially remember one play when Joe Alexander, the Giants' center, almost twisted my head off in making a tackle. It was clear we were all beginning to show the wear and tear of our crowded schedule. After that encounter with the Giants, the Bears were no longer able to field a team free of injuries. We were due in Washington, D.C., on Tuesday to play another exhibition, but Pyle and I decided for business reasons to remain in New York an extra day. Opening up our hotel room to all callers, we collected about $25,000 in certified checks for endorsements of a sweater, shoe, cap, doll and soft drink. We turned down a tie-up with a cigarette company because I didn't smoke. We also signed a movie contract that day. ...   Red Grange with the Bears Arriving in Boston on Wednesday morning, December 9th, for the game with the Providence Steamrollers, the Bears were in a pitiful condition, with many of us bandaged from head to foot. I was in particularly bad shape. I had hurt my left arm in New York and it was still badly swollen. ... the Bears' trainer worked feverishly all night on the train to help ease our miseries and prepare us for the next assault. Under such conditions it was to be expected the Bears would not fare well against the Providence eleven. We lost 9-6 and the best I could do was 18y on five tries. I attempted three forward passes and had one intercepted. My arm was in such pain I couldn't do anything right. ... I was booed for the first time in my football career in the Boston game. ... It was reported I was a very dejected young man after that experience in Boston. Babe Ruth was supposed to have come into the locker room following the game to offer some sage words of advice. ... The fact of the matter is I saw Ruth before the game only when we took some publicity pictures together. His personal remarks were limited to, "Hi-yah, kid. How you doing?" We then got to talking about baseball. We were due in Pittsburgh the next day, December 10th, for an exhibition with the Pittsburgh All-Stars in the Pirates' ball park. I should never have played. My left arm was swollen to almost twice its normal size and the pain was excruciating. Before the game Alvin "Bo" McMillin, the one-time All-American from Centre College ... dropped in to say hello in the locker room. When he saw the condition of my arm, he strongly advised my sitting out the game. I should have followed his advice, but it was impossible on such short notice. Our contract with the local Pitt promoter called for my playing at least 30 minutes, as in all previous games with the Bears. It had rained heavily the day before and when it was followed by freezing temperatures. the tURf on the playing field became like a ripped-up concrete road. We began the Pitt game with ten men on the field and several minutes went by before anybody realized it. The Bears, with no able-bodied men left among them, matched to see who would start. Before the game was a few minutes old I was struck on my sore arm when I threw a block ... The physician for the Pittsburgh club ordered that I be taken out when it appeared a blood vessel in the arm ruptured and was causing a hemorrhage. I played no more that day. Unaware at the moment that I was severely injured, the crowd jeered as I left the field. ... Red did not play in any of the remaining four games of the inhuman tour. Money was refunded to fans in several of the cities. Whatever It Takes to Win

Big Eight Football, John D. McCallum (1979)

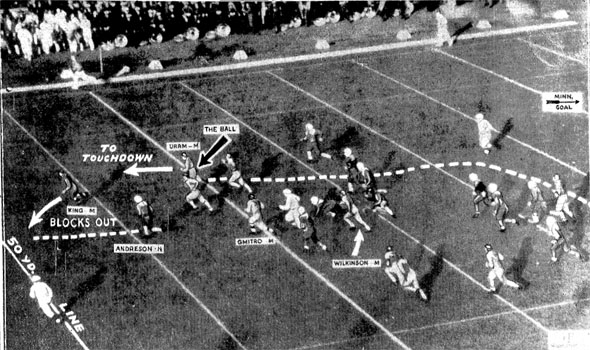

LSU in 1916 On the bench during a game, Bible was - well, seldom on the bench. Space was reserved for him there, but he almost never occupied it. The players not in the starting lineup always stood up, close to the sideline, at the kickoff, and D. X. stood with them. But when they sat down, he remained on his feet. The chances were that if you put a pedometer on him, you would have found that he covered more ground than any of his halfbacks in the course of a game, and this is not knocking the young men who played halfback for him. Remember, they were in and out of the game, while Coach Bible "played" 60 minutes every Saturday. He roamed up and down the sideline, watching the players, the officials, occasionally yelling at them all, darting back to the bench to talk to a player going into the game, striding out to meet a player he was removing, consulting with his assistants. The players sitting on the bench were supposed to watch the game closely. There were times, however, when a couple of them could not see what was happening because the coach was standing in front of them. None of his players would have been too surprised had he ripped off his coat and torn right into the ball game. They knew that the temptation to be out there was strong upon him sometimes. Bible failed to win the Big Six conference only in 1930 and 1934. ... On the negative side, Bible lost four out of five games to Minnesota, coached by Bernie Bierman, and the best he could get out of eight games with Jock Sutherland's Pittsburgh teams was scoreless ties in 1930 and 1932. This, however, did not detract from his stature very much, because the Gophers and Panthers were top national powers and the Huskers usually pushed them to the limit. Even though Nebraska lost to Minnesota, 7-0, and to Pitt, 19-6, in 1936, the Cornhuskers ranked No. 9 in the national polls. The Gophers finished No. 1, the Panthers No. 3. The loss to Minnesota rates among the historic heartbreakers, for there were only 59 seconds left when Andy Uram, taking a lateral from QB Bud Wilkinson on a punt return, raced 75y for a TD.  Winning TD for Minnesota vs Nebraska 1936 Winning TD for Minnesota vs Nebraska 1936The aftermath emphasized Bible's ability as a practical psychologist, even though he was, in effect, again calling on character. The next game was with Indiana, and the Hoosiers led the Cornhuskers 9-0 at the half in great measure because UN was still "down" from its effort against Minnesota. The halftime scene in the Nebraska dressing room was something to remember. D. X. just threw away technical details and concentrated on psychology. He challenged his players' desire to win, their courage to fight back. He offered starting positions to the first eleven men who wanted badly enough to beat the rest of the team to the exit. They lit out for the door. Bible beat them to it. Then he stood blocking the way, insisting they weren't ready. A genuine mob scene developed. Normally affable players knocked each other down fighting to get out. Some squared off and fought. The pandemonium was terrifying. And it worked. Nebraska came back to win the game, 13-9; and they played the second half with only eleven men.

"Coach Bible was a forceful leader," said one of his Huskers years ago. "He had courage to match any situation. No matter the problem, he could take charge. He had the ability to organize a team into a loyal and spirited group. He demanded discipline and respect, and he got it." When Dana X. Bible left Nebraska for Texas in 1937, he negotiated one of the best contracts in the history of college coaching. The Longhorns wanted him so badly that they gave him a twenty-year contract, the first ten years as coach and athletic director, at $15,000 a year. Before they could agree on the deal, the Texas legislature pondered and debated. Fifteen grand meant that Bible would be getting more than the college president. The legislature resolved the impasse by raising the president's salary. Bobby Layne

I Love Oklahoma, I Hate Texas, Jake Trotter (2007)

In Detroit, it's known as the Curse of Bobby Layne. After Layne led the Lions to a third NFL championship, Detroit traded its franchise quarterback to Pittsburgh in 1958. In response, legend has it Layne said the Lions would not win for 50 years. Cursed, Detroit has endured through the worst winning percentage of any NFL team over the last 50 years and has yet to play for another championship. But the Lions weren't the only ones to be cursed by the "Blond Bomber." Layne grew up in Dallas and played high school ball at Highland Park with the great Doak Walker, who would star at SMU before teaming up with Layne again in Detroit. "Bobby Layne never lost a game. Time just ran out," Walker once said. "Nobody hated to lose more than Bobby." Nobody loved having fun more than Layne, either. After convincing him to come to Austin, UT coach Dana X. Bible couldn't wait to see what Layne could do. Bible would have to wait another day. Layne didn't show up for the first practice. When Bible asked where he was, Layne answered, "Coach, you don't even want to know." Like fellow UT quarterback James Street, the hard-partying, hard-drinking Layne doubled as a star pitcher for the UT baseball team. Once, while pitching a no-hitter against Texas A&M, Layne drank 10 beers in the dugout to kill the pain in his foot, which he cut open partying the night before. When asked how he could party all night, then play so well the next day, Layne replied, "I sleep fast." It wasn't long before Bible charged 4'11" Rooster Andrews, the team's water boy/ kicker, to keep Layne out of trouble. Late one night during Layne's first season at Austin, he woke Andrews up with a random question: "When you're back there drop-kicking on extra points, I wonder if we could fake the thing and you could throw it to me on the left flat?" The two would successfully unleash the play against the Sooners that season, but only after the 17-year-old Layne had already thrown two touchdowns. UT won the game 20–0. Layne missed the '45 meeting with OU— which the Horns won anyway, 12–7— while serving in the Merchant Marines. But in '46, he returned to the rivalry with a vengeance. Outdueling OU's backfield combo of Darrell Royal and Jack Mitchell, Layne scored a touchdown in the first quarter to propel the Longhorns to a 20–13 victory.    L-R: Bobby Layne, Doak Walker, Dana X. Bible The Sooners would get no breaks in '47 from Layne—or from the officials. With Texas at the OU 2-yard line and only a few seconds remaining before halftime, UT halfback Randall Clay was stopped before the goal line. Official Jack Sisco initially signaled "touchdown," then changed it to "timeout" when it became obvious the Longhorns hadn't scored. Sooners fans screamed that the half was over, but Texas was given one more play— a play that would live in Oklahoma infamy. As Layne handed off to halfback Jimmy Canady, the ball squirted into the backfield. What happened next remains in dispute. The ball came into Layne's hands while he faced the end zone. Crouching, Layne spun around and pitched the ball to Clay, who then ran around the end for a touchdown. OU coach Bud Wilkinson and his players protested that Layne's knee had been down. But officials let the play stand. The touchdown gave Texas a 14– 7 lead and immense momentum heading into the locker room. Years later, on the matter of whether his knee was down, Layne would say, "To tell you the truth, I promise you I don't know myself to this day. The film didn't show it. Really and truly I don't know, because of the heat of the ballgame, whether I had my knee down or not. I couldn't tell you." The Longhorns went on to win 34– 14, and after several more controversial calls in the second half, OU fans began hurling hundreds of bottles and seat cushions onto the field. The game became known in Oklahoma as the "Sisco Game." But in the dressing room, OU All-America center John Rapacz acknowledged the No. 1 reason why they hadn't won. "It's the same old story," he said. "We play our hearts out, and that Layne beats us." The Johnny Bright Case Football Nation: Four Hundred Years of America's Game from the Library of Congress

Susan Reyburn (2013)

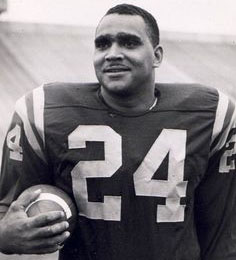

"John was ambushed for two reasons: One, he was a hell of a football player. And two, he was black," said Gene Macomber, a teammate of Drake's Johnny Bright, a leading contender for the Heisman Trophy in 1951. What occurred that season in Stillwater, OK, was emblematic of what other black players had endured, but none so publicly.

The mood in town was not especially welcoming when the undefeated Drake Bulldogs arrived to play 1-3 Oklahoma A&M (as Oklahoma State was then known). Bright, Drake's only black player, was not permitted to stay at the team hotel, instead finding accommodations at the home of a black minister. And the word was that the Aggies would be gunning for Bright. "They told me Johnny wasn't going to finish the game," said Macomber, who had visited a local barbershop that morning. And so it was. Three times in the first quarter, Aggie tackle Wilbanks Smith viciously struck Bright in the face, knocking him out cold. In each instance Bright was hit well after he was out of the play and without the ball. No penalties were called. The dazed Bulldog, his jaw broken, then tossed a 61y TD pass and left the game, catching sight of a sign in the stands reading "Get the nigger." The Aggies went on to a 27-14 victory.   Wilbanks Smith smashes Johnny Bright in the face long after the ball has been handed off.

A&M coach J. B. Whitworth denied that Smith had been instructed to go after Bright (despite A&M student eyewitness admissions to the contrary). After the jawbreaking hits, Smith made a jaw-dropping statement, saying he was sorry if he had "overcharged Johnny." The incident might have ended in a "Drake said, A&M said" stalemate had not the Des Moines Register run indisputable proof of the outrage on its front page the next day. Don Ultang and John Robinson's photographs clearly depicted what Life magazine would call "the year's most glaring example of dirty football," and the New York Times would later name this "one of the ugliest racial incidents in college sports history."

The story drew national attention and widespread criticism of A&M, whose athletic council, even after seeing film footage of the plays, pronounced the hits as merely "illegal blocks" and "just another football incident." Neither the college nor Coach Whitworth disciplined - or even reprimanded - Smith. Infuriated, Drake presented its case, photographs and all, to the Missouri Valley Conference, asking that it take action. Officials declined to do so, prompting Drake to withdraw from the league. In a supportive gesture, Bradley University withdrew as well. The University of Detroit, scheduled to play A&M next, received "scores of letters" according to its coach, asking that his team avenge Bright. Johnny Bright played briefly once more that season, finished fifth in the Heisman voting, and accepted an offer to play professionally in Canada, where he enjoyed a Hall of Fame career and later became a school principal. As a result of the Oklahoma A&M game, Drake downgraded its football program, college football helmets were reconfigured to include face bars, and the NCAA made hands-to-the-helmet moves illegal. In the spring of 1952, Ultang and Robinson won a Pulitzer Prize for their series of photographs. Bright refused to be bitter about what he deemed a life-changing event. "Because one person chose to do wrong, not all of the good derived from sports should be overlooked," he said shortly after the game. "The letters I have received from people all over the country indicate [that] most people are for fair play, regardless of race, creed or color. Among those letters were several ... from Stillwater." Newspapers around the country reprinted the award-winning images of the vicious hits on Bright. In 2005, Oklahoma State issued an apology for what had occurred on its field. The next year, Drake named its new gridiron Johnny Bright Field. Nobody Works Harder

It Never Rains in Tiger Stadium, John Ed Bradley (2007)

The 1979 LSU Tigers faced #1 USC in Tiger Stadium. It was already known that would be Coach Charlie McClendon's last season at LSU. Bradley played guard. When it was over, I raised a fist and beat the ground until Big Ed [OT Stanton] put his arms around me and helped me to my feet. I could've kept punching the turf all night, but it wasn't going to change anything. Back in high school, Coach Guidry had told me never to walk off a football field unless I was physically unable to run, so I buckled my chinstrap and started for the locker room, jogging in the weary way of a man who didn't have a play left in him. As I passed under the goalpost, a group of kids began yelling at me from the seats at field level. I removed an elbow pad and tossed it to them, adding the other one and my hand pads when more kids showed up to beg for souvenirs. I'd have given them everything and walked into the locker room naked, but the equipment manager, I knew, wouldn't have taken kindly to my largesse. At the metal door that led to the chute, I stopped and spoke to a student trainer about my chest. There was blood on my jersey and he wanted to know how I'd made out. "I did fine," I lied. Then I turned and had another look at Tiger Stadium.

Thousands of fans were still in their seats, beating their heels against the aluminum bleachers and cheering us on, even though our game with top-ranked USC had ended. We'd lost 17-12 when the Trojans scored with only 32 seconds left on the clock, ruining our dream of pulling off the biggest upset in school history. Somebody needed to tell the fans that the wrong team had won and it was time to put away their whiskey flasks and go home. ... Maybe I imagined it, but no sooner had I asked the question than the crowd erupted with more noise. You like to make the home folks happy, but you typically don't do that unless you win. Going back to my days as QB of the Opelousas Junior High Cavaliers, I couldn't recall any fan who ever stood and cheered for me when I left the field a loser. Tonight had changed my understanding of what it meant to win. In the days leading up to the game, even local oddsmakers had predicted that USC would beat us by twelve points. The Trojans, widely advertised as the finest collection of football talent ever assembled on a college team, had All-Americans and future pro stars on both sides of the ball. In fact, the 1979 Trojans had twelve future NFL first-round draft choices and 31 overall picks. Charles White and Marcus Allen were the team's running backs; they each would win the Heisman Trophy before graduating to the NFL. T Anthony Munoz would become an eleven-time Pro Bowl selection with the Cincinnati Bengals and a member, in 1998, of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. G Brad Budde would win the Lombardi Award and play for the Kansas City Chiefs. Dennis Johnson, a future Minnesota Viking, was the Trojans' best LB, and Dennis Smith and Ronnie Lott played in the secondary. Smith was a ferocious hitter, but Lott, a junior, was the most physical DB the college game had ever seen. He'd spend 14 seasons in the NFL, most of them with the San Francisco 49ers, where he would play on four winning Super Bowl teams and become famous for punishing licks that forced fumbles and knocked out lights. By contrast, no one had heard of our guys outside of Louisiana towns like Plaquemine, Baker, Bossier City, and Ville Platte. So how could we have played USC so close? I had no trouble with that one: We had Mac. LSU had been fielding football teams since 1893 and playing games at Tiger Stadium since the first phase of construction was completed in 1924. Fans for the home team had witnessed Billy Cannon's Halloween night punt return for 89y and a TD against Ole Miss in 1959, and they'd watched as Bert Jones passed to Brad Davis in the EZ with time expired to beat the Rebels in 1972. They'd seen Tiger greats like Steve Van Buren and Y.A. Tittle, Jimmy Taylor and Tommy Casanova. Now they had the USC game to remember. The game hinged on a face-mask penalty against Benjy Thibodeaux, one of our DTs who, from my vantage point on the sideline, looked wholly innocent of the crime. [Editor's note: The video of the game shows he was guilty.] We were leading 12-10 with about two minutes left to play, and USC's final drive to the EZ would've ended if not for the call. Schooled since infancy on the consequences of displaying "unsportsmanlike conduct," I was never one to blame losses on the officiating, but tonight I felt ripped off.    L-R: John Ed Bradley, Coach McClendon shakes hands with Ronnie Lott, Benjy Thibodeaux I wrapped my middle with a towel, walked back to the chute, and stood on a scale. I was down to 222 pounds, 21 lighter than when I'd suited up. That was nearly a tenth of my body weight, lost in the time it took to watch a couple of movies. It was also 60 lbs lighter than one of the USC nose guards. I pulled on a T-shirt that said LSU FOOTBALL and stepped into a pair of gym trunks and flip-flops, and then I reported to the weight room where reporters were interviewing players and coaches. "I've been going to ballgames since I was in school here," one of the older newspapermen told me, "and it ranks up there with the greatest ever played in Tiger Stadium. It surely was the loudest. They'll never forget this one." ... I waited until he was finished writing in his notebook. "But we lost tonight," I said. "The other guys won." "Tell those people that." And now he pointed a pen upward, indicating the fans still beating their feet against the metal seats above us in the stadium. More than anything, we'd wanted to win it for Coach Mac. Refusing to acknowledge the many other factors that had led to his ouster, we'd had it in our heads that a victory over the country's most celebrated team might be enough to prompt the Board of Supervisors to extend his contract another five years, or at least until he reached a more suitable retirement age. If we could humble the Trojans, I'd told the guys at practice that week, how could the school let him go? Now, with the loss, I felt as if we'd let him down. "I guess it wasn't meant to be," Big Ed said later in the dorm. "I guess God wanted something else for us," I answered, even as I lay on my bunk and wondered if God really played a role in the outcome of football games, including those as big as ours with USC. Unable to sleep, I staggered out in the hall and waited with some of my teammates for curfew check. They were sitting on the carpeted floor in a loose arrangement on their knees and shoulders, others wrapped in bandages. A few had deep, open cuts on their arms and abrasions decorating their chins and foreheads. Like me, they'd been unable to get their bodies to shut down, and they knew that to sleep meant to wake up tomorrow with the game result freshly printed in the newspaper, thus making it irreversible. At this moment it still seemed that if we held on to the night, we held on to the possiblity that our fate could be overturned. Benjy wouldn't get the call, the Trojans wouldn't punch it in, Coach Mac wouldn't lose his job after 27 years. If there was any fairness in the world, we'd get what we earned rather than what was dealt. At half past two, a dorm monitor came by and announced that Mac had suspended curfew for thenight, as a gift to us. I hopped to my feet and walked from room to room, knocking on doors and shouting "No curfew, no curfew tonight." Only a couple of players took me at my word. They came out, pulling on their jeans and shoes and stumbling toward the exits. The rest told me to go away. Toward dawn I found myself seated in the grass on the levee with a girl I knew. ... As the sun came up, I got to my feet and started down the grade to the Impala parked on a River Road turnaround. The girl, following close behind, stopped about halfway down and slapped her legs. "Mosquitoes 'bout to eat me alive," she said. Somehow I knew I'd never recover. Origin of the West Coast Offense

Building a Champion, by Bill Walsh with Bill Dickey (1990)

When I was at Stanford, I searched for and finally found, in a warehouse, film of Clark Shaughnessy's 1940 Rose Bowl team. Watching that reinforced my feeling about the use of the man-in-motion. Shaughnessy was using plays and formations very similar to those we were running at Stanford nearly forty years later.

The man-in-motion can be used to force the defense to change in pass coverage and run support. As an example, in a game against Houston when I was at Cincinnati, we began to use our flanker in motion with two TEs, the simplest of tactics. When our flanker crossed the formation, Houston failed to adjust by bringing up a man to stop the sweep. So, when we put the flanker in motion, we'd run the sweep to the side where the flanker had gone, because he gave us an extra blocker. Other teams would adjust by sliding their strong safety back, and their weak safety would come up when you put your man in motion. Usually, the weak safety is the faster of the two. So, each week we'd identify and analyze the strong safety. If the strong safety lacked speed and we'd employ a flanker in motion, forcing the strong safety into the middle and the weak safety up to stop the sweep as the flanker moved to his side of the formation. Then we would send Isaac Curtis down the middle, because the strong safety wouldn't be able to stay with him. We also used motion to force the defense to react and leave a particular area of the field open or vulnerable. When we put a back in motion, often it was to see if the weak safety would come out of the secondary to cover him. A typical play would be the FB going in motion and weak safety coming over to cover him, which left the middle wide open for a post pattern by a WR. That also indicated the defense was blitzing, because the safety had to come up to cover. If the safety stayed back, we knew the blitz was unlikely.     L-R: Bill Walsh, Isaac Curtis, Bob Trumpy, Steve DeBerg L-R: Bill Walsh, Isaac Curtis, Bob Trumpy, Steve DeBerg Utilizing the man-in-motion can be extremely valuable to the QB in identifying the form of pass coverage to expect. If a back goes in motion and LBs begin to loosen, the QB can expect a zone. If a LB immediately moves with the back in motion, the QB can see man-to-man coverage.

We also used motion to flood a zone defense with additional receivers. Generally, when the LBs drop back to cover a pass, they are drilled to defend against a traditional formation with a SE on one side of the field and a flanker on the other. If you put a man in motion, there's another potential receiver in that area, so we could stretch the zone wide open, outnumbering the defenders. Either the defense would overadjust, so you could hit a hooking receiver, or they wouldn't cover the man in motion, so you could throw to him. We used the TE in motion first by mistake. Cincinnati was playing the Raiders in Oakland. In Q3, Bob Trumpy lined up on the wrong side by mistake. He had to shift over quickly to the other side, and all hell broke loose. At that time, the Raiders had very specialized people. They had a weak-side LB, they had a strong-side LB, they had a DE who only played on the TE side, and they would shift their two ILBs. So when Bob shifted, they all ran into each other in the middle of the field, trying to adjust. Upon returning home and studying the films, Bill Johnson said, "What would happen if we purposely did that?" We looked at each other and doubled over laughing. At that moment, the "TE in motion" was created. Initially it caused all sorts of havoc. But when he came to the line of scrimmage on the other side, he had to be stationary for a second before the ball could be snapped. Soon, some teams adjusted their defense as we shifted. The next thing we did was to put the flanker up on the line and the TE off the line. We then put the TE in motion, so he wouldn't have to stop and set himself. That created all kinds of problems for defenses. First, we could force a major adjustment if teams were playing weak-side and strong-side LBs. (The strong side is considered where the TE locates himself to add a blocker for running plays.) If a weak-side LB was fast but had trouble handling a big, blocking TE, we could force him to defend on the strong side any time we wanted, simply by moving the TE to his side. Also, the TE in motion might be split out 5y and be moving to the outside when the ball was snapped, so he could become a more dangerous receiver and a different type of blocker. By the time I got to the 49ers, I was using several combinations of a back in motion, the TE in motion, the flanker in motion. We were able to keep defenses off balance, so with receivers like Mike Schumann and Freddie Solomon, Steve DeBerg set NFL records for passes attempted and completed. Our style of play was often characterized as "finesse" football - intended by many as a put-down. The point was that we weren't really a tough, physical team. Well, if you consider finesse to be skill and technique, yes, there was a lot of skill and technique in everything we did. There was much more attention to detail. If that's finesse, so be it. Quite a Plane Ride

Ray Glier, How the SEC Became Goliath: The Making of College Football's

Most Dominant Conference (2012) Messengers kept coming down the aisle every few minutes. "Pitt's winning." They walked back and forth a couple more times on the flight back to Baton Rouge, ... giving the partial score of the West Virginia-Pitt game. It was too tedious for Les Miles and he finally had enough. "I'm not the guy who wants to get a partial score," the LSU coach said. ... "Give it to me at the end."

"Playing for a conference championship is awfully damn important here," Miles said. "Even this past season [2011] we're going to hang two banners in this building. A Western Division banner and the SEC banner. Those are damn important things and they were dam important in 2007." ... When the plane landed, Miles heard the final score: Pitt 13, No. 2 West Virginia 9. It had all been lined up for the Tigers; LSU had a chance to play for the national championship. West Virginia had been a decisive favorite against the Panthers, who were just 4-7, but the Mountaineers unraveled. Their sensational QB, Pat White, dislocated his thumb in the second quarter, the Mountaineers lost three fumbles, and WVU became the sixth team ranked No. 2 in 2007 to lose. Pretty luck, huh? For LSU, that is. Miles sitting in his office in Baton Rouge four and a half years later, just smiled. Pat McAfee, an NFL-caliber kicker, ... had missed two makeable FGs for West Virginia. How could that happen? Miles turned his right hand over, the palm was up, and he kept smiling and gave a little shrug. A Bible was a few feet away on his coffee table. You knew what he meant. A blessing had flowed into his open palm. ... "We got on the plane having won the conference championship," Miles said. "We got off the plane with a chance to win the national championship. Are you kidding me? How wonderful all that was." It was not so wonderful for West Virginia. After this bitter loss on a bitter-cold night, plenty of ill will followed. Some students gathered outside McAfee's off-campus apartment and started shouting threats and honking horns. Texts warned of abuse for missing FGs from 20 and 32y. His car was vandalized and then there was the ultimate smack talk: a death threat. "It was just a nightmare," West Virginia coach Rich Rodriguez said after the game. "The whole thing was a nightmare." For LSU, it was euphoria. Just to make sure the BCS did not dare slip anyone but LSU into the National Championship Game against Ohio State, Miles was given directives on the tarmac on whom to lobby in the media to make it all secure. Les the Lobbyist got on ESPN and started talking up the Tigers. Undefeated in regulation, he chimed, a phrase coined by his wife, Kathy. LSU (10-2) had lost to Kentucky and to Arkansas, both in triple overtime. They had clobbered No. 9 Virginia Tech and beat Tim Tebow and No. 5 Florida. They won at No. 18 Tennessee and beat Nick Saban's first Alabama team in Tuscaloosa. "Georgia wanted to say it was the hotter team and it should play Ohio State," Miles said. "Well, I said the hell with them. We were the better team. They didn't even win their side of the conference. We had accomplished greatly, even if we didn't get in that last game. It didn't make any stinking difference where we played after we won the championship of this conference. But I'm glad we got the shot. It was going to give us a chance to get healthy. Glenn [Dorsey] needed the time off, and Matt Flynn [QB] didn't even play in the conference championship game. When we got healthy, well, you saw it." The Tigers waxed the Buckeyes. They were good and lucky.    L-R: Les Miles, Glenn Dorsey, Matt Flynn, Jordan Jefferson The players, meanwhile, treated it as if they belonged to neither Saban nor Miles. They were LSU guys. That's how LSU has remained near the top of the heap in college football the last five seasons: Louisiana pride. People around the state recognize that high school players, staying in state, can deliver championship after championship. "Eighty percent of the guys in the program were from Louisiana," said Craig Steltz, the safety for the 2007 team. "It doesn't matter for a lot of guys who the coach is, Saban or Miles. We are going to uphold the tradition of the program. We are going to wear the white jerseys and gold pants at home. We're going to run through the goalposts and walk down the [Victory] hill. The tradition is what has to be upheld through the years." That was fine by Miles. Players first, coach second. Miles made the mistake one time of getting the order wrong. It still bugs him. He remembers referring to his guys after one game while he was the head coach at Oklahoma State as "they," and he has never fogotten it. "We were at Kansas State, and we got the s*** kicked out of us," he said. "We had suspended two FBs and had some injuries and it was just a bad day, and I, as a young head coach, put myself in a separate place and said 'they' when responding to a question. I had to apologize to my team. It so bothered me." ... "We're playing Tennessee in the SEC Championship Game (2007). Matt Flynn is my holder; he's out, injured. Ryan Perriloux is my new holder. There is just a little difference in how it all needs to mesh on the kick. Those things you as a reporter are never going to get from me." Colt David missed a 30y FG before the half in the 21-14 win over the Vols. David did not miss many 30y FGs in his career, but he had an alibi, a new holder. Miles refused to lay blame or enlighten. It's why Miles did not jump down Bobby Hebert's throat publicly in the press conference following the 21-0 loss to Alabama in the national championship in January 2012. Hebert, a former NFL QB, popular radio talk-show host in New Orleans, and father of one of Miles's players, asked an agitated question about why Miles did not change QBs against Alabama with the offense flailing away. The answer was pretty obvious: Jarrett Lee, whom Hebert wanted in the game, had wilted in Tuscaloosa in the 9-6 LSU win in November when Lee had to pass against Bama pressure. Miles wouldn't say publicly that Lee was not going to handle the frother-up Alabama defense any better in the rematch. ... "You're never going to get comparisons from me for Jordan Jefferson and Jarrett Lee in that championship game," Miles said. "I am going to stand for both of them. I love both of them." Even after Jefferson went on an Atlanta radio station a month after the game and bashed the LSU game plan against Alabama, Miles kept quiet. Others in the program were incredulous at Jefferson's sniping. Miles had stood behind Jefferson after the QB was in a bar fight before the 2011 season and stuck with Jefferson as QB after a number of poor passing performances. It wasn't just the game plan that cost LSU against Alabama; it was Jefferson's mishandling snaps from center and penalties that ruined some plays. Miles needed a flak jacket with his own side taking shots at him, but he was mum. ... He is considered a player's coach, but he does not coddle players. He tells them rather directly, "When you sign up to come to this school, you are signing up to really exceed expectations." Lincoln Riley's Lucky Break

ESPN the Magazine, Dave Wilson (2012)

In 2002, Lincoln Riley desperately wanted to be a college QB - but that old busted-up arm limited his options. ... Two years earlier, Mike Leach had brought a high-scoring spread offense to Lubbock ... His teams immediately began averaging upward of 50 pass attempts per game, leading the nation. ...

Riley walked on at Texas Tech - and made the team. Aiding Riley's cause: Leach values smarts in his QBs as much as he does physical attributes. "Riley had a brain that wouldn't stop. He sees things once and remembers it," says David Wood, his high school coach. "I thought he might end up working at NASA." Still the QB room that year was crowded: Kliff Kingsberry, who threw for more than 5,000y as a senior in 2002 and set seven NCAA records in his three years as a starter at Tech, was the test pilot of the Air Raid in Lubbock, proving it could fly. Also in that room: B.J. Symons, who would set the NCAA passing record with 5,833y in 2003, and Sonny Cumbie and Cody Hodges, who would each pass for more than 4,000y in a season as Red Raiders starters. One other problem for Riley: "He was awful," says Houston coach Dana Holgorsen, Tech's inside receivers coach in 2002. "It was so bad that me and Sonny Dykes called an intervention with Leach. We said, 'What are you doing? Team morale is low because you're giving this kid reps. Our receivers are running routes knowing there's zero chance the ball is gonna get to them.'" Leach argued that while Riley didn't have the arm the other QBs did, he had a high football IQ. "As a player, he asked questions all the times," Dykes, now the SMU coach, says of Riley. "He probably wasn't a good enough player to ask all those questions, but it never bothered anybody because he was so eager." And so it was that Leach asked Riley to hang up his pads and become a student assistant. ... He would spend the next seven years on the Red Raiders' sideline, graduting to graduate assistant in 2006 before becoming the youngest full-time assistant in the country ... when he was named receivers coach in 2007 ...    L-R: Lincoln Riley, Mike Leach, Sonny Dykes, Dana Holgorsen A few years later, when [Bob] Stoops decided his Oklahoma offense needed a jolt, he fired up his computer, looked up the top offenses in the country and alighted upon East Carolina. ... When Stoops hired Riley in January 2015, his red-dirt Air Raid education proved the football equivalent of a musical prodigy going to Juilliard. ... Riley was an instant success as offensive coordinator at OU, so much so that one day in June 2017, Stoops decided to hand over the whole dang thing to Riley and abruptly step aside. ... Stoops thought the kid ... should become the coach at Oklahoma before someone else got to him first. And now, two years later, Riley - fresh off record-setting seasons by [Heisman Trophy winners] Mayfield and Murray - has become the most coveted coach in football. ... He has routinely batted away questions about interest from the NFL, specifically the Dallas Cowboys, and landed a five-year contract extension in January, bumping his annual salary at OU to $6 million. Cody Worsham, LSU-Texas A&M Gameday Program 10/30/19

At the heart of everything Joe Burrow does - the eye-popping statistics, the awe-inspiring toughness, the game-changing leadership - is an undeniable will to win. If you're looking for the foundation for Burrow's 2019 run at the Heisman Trophy and national championships, the platform upon which he's mounted a campaign as one of the best QBs to every play in the SEC, it's a competitive drive he was seemingly born with. Ever since he first picked up a ball, Burrow had to be the best, and he's spent every day since collecting characteristics - grit, accuracy, poise, and everything else he's displayed all season - geared to making him unbeatable. "He's always wanted to be the person with the ball in his hand and be the person scoring points," his mother, Robin says, "whether it was soccer or basketball or baseball or football. It's just in his DNA, I guess." "He's the most competitive dude on the planet," says Sam Vander Ven, Burrow's childhood friend and high school teammate. "Without a doubt. Whether it's a video game or anything outside of sports, he's a ruthless dude." The first time his parents saw that ruthlessness on display was after a fourth grade baseball tournament. Burrow never paid attention to trophies, his parents say. They were trivial consequences from the thing he was really after - scratching that unending competitive itch. The only time he ever noticed one was when that itch went unscratched. "The only trophy that he evr paid attention to was when he got second in a baseball tournament, and one of his best friends had thrown the second place trophy in the garbage can," says Jimmy, his father. "So we're driving home and we're just horrified that that happened. Joe gets home, and we go up to his room and about an hour afterwards, and he had dismantled the second place trophy." That provided an opportunity to teach Burrow a lesson in humility and losing with grace. Even as he absorbed that lesson, it didn't make the losing less intolerable to his disposition. As much as he loves winning, Burrow may hate losing even more. There's plenty of evidence to support that claim. Like his senior season basketball pictures, taken just three days after Burrow lost the state championship game in football. The hurt in his eyes is evident even today, five years removed from the defeat. "He carried that loss with him quite a long time," Jimmy says.   L-R: Joe Burrow runs against Bama, Carried off at Tuscaloosa After that interception, Burrow changed the game plan. He started targeting the defensive back who'd intercepted him in the first quarter as often as he could. Three quarters, 300y, five TDs, and a 55-9 win later, Burrow made good on the debt. "Joe definitely made him pay," Tom says. It's something his teammates at LSU notice. Sometimes, the worst thing you can do in practice is intercept a Burrow throw. You'll spend he rest of the practice in the center of his target, which is a dangerous place to live. "I see it in practice all the time, in 7-on-7s," says LSU punter Zach Von Rosenberg. "Guys that pick the ball off, he's infuriated. He's like, 'Give me the ball. Let's do this again.' It's a switch that gets flipped that turns him into that massive competitor." Perhaps the only thing that gets Burrow going better than a pick is getting hit. That's something his high school offensive coordinator, Nathan White, realized as early as Burrow's sophomore season, when the offense got off to a sluggish start against an inferior opponent. Man, White thought. I'm just going to run Joe until he gets into this thing. He got into that thing, alright. Burrow would finish the game with 161y on 23 carries, and for the rest of his prep career, Burrow ran the ball on the second or third play of every single game. To this day, White ... runs his QBs early in games to get them going. "He started rolling, got a few hits," White says. "He was like a different man after that." "I enjoy getting hit sometimes," Burrow says. "It makes me feel like a real football player instead of a QB. People can look down on QBs sometimes if they're not taking hits. I like mixing it up in there." Perhaps no hit hurt Burrow last year quite like LSU's seven-overtime loss to Texas A&M. He took plenty of hits in that game, throwing for 270y and three TDs while adding 131 rushing yards ... and three TDs on the ground. It was, by all means, a heroic effort, and it was, perhaps, the catalyst to his 2019 run as college football's best QB. But it took a toll, physically and emotionally. After 39 passes, 23 carries, six sacks, and seven overtimes, Burrow passed out in the locker room and needed an IV bag, cookies, and apple sauce to recover. "That was the second dagger," Robin says, comparing the A&M defeat to the state championship game loss his senior season at Athens. Like a hit or a pick, though, Burrow has always had an ability to catalyze defeat, to harness heartbreak and transform it into motivation and clarity of thought. He takes them hard, but they don't hold him back. In fact, they have the inverse effect. "He can channel that frustration into positive energy," Robin says. "I think he definitely internalizes things a little bit, but uses it in a positive way." That's why Jimmy says Burrow entered 2019 with three games circled on the calendar. First was Florida, who handed him his first loss as LSU's starter in 2018 and clinched the win with a pick-six. One year later, Burrow completed 21-of-24 passes for 293y and three TDs in a 42-28 win over the Gators. Then came Alabama, who shut Burrow and LSU out in 2018, 29-0, in a game he played with an injured shoulder. One year later, Burrow went into Tuscaloosa and hung 393y on the Tide, leading LSU to a 46-41 victory, Next us is A&M, and be assured that Burrow remembers that dagger. "I know he looks forward to three games this year ...," Jimmy says. ... "In his mind, those were failures. In games like that, he tries to focus on not letting things like that happen again." That's the will to win that Burrow's tapped into all year, his entire career. It's the force behind everything he's done on his way to the brink of everything he's ever dreamed of. It's what makes him special, and it's what should keep opponents up at night. Joe Burrow's comin'. And he ain't backing down. |