|

Young Walter's Game The Hidden Game of Football, Bob Carroll, Pete Palmer, John Thorn (1988)

Walter Camp As in rugby, a player could run with the ball, and when he was about to be tackled, he could either kick it away, throw it away, or keep it and go down in a heap. If he chose to kick, he could either try for a goal or send the ball off to the other team. If he threw the ball away - hopefully to a teammate - the rules said he could not toss it forward, only backward or sideways. If he let himself be tackled - certainly the least preferred option - a "scrum" followed. A scrum was like a face-off in hockey. Everyone gathered around in a tight circle ..., and the referee skittered the ball in between the two "centers" for each team, who kicked at it until it bounced to a teammate. Whoever got the ball took off like a scalded dog until he too was about to be tackled. At which point, he had the same three options of kick, throw, or be dumped. ... As in soccer, all the scoring was done by kicking the ball. Even if a player ran the ball over the goal line, all he got was a free try to kick a goal. To count, just as with today's football kicks, the ball had to go over a crossbar set on matched posts placed on the goal line. Young Walter Camp proved to be a wizard at this hybrid game; the best in the world, his friends said. Admittedly, it was a pretty small "world" in those days, what with only Yale and a couple of other northeastern college playing the game, but Camp's talents as well as his brains made him a leader every time a group got together to suggest new rules. By 1880, he was fed up with the free-for-all, catch-as-catch-can jumble he'd been playing; he decided to develop a more regimented affair wherein a team could know it was going to have possession of the ball for a bit and give some thought to its next move. In other words, the brainy Camp wanted a game where his quick mind was as useful as his quick feet. Working with what he already had, he suggested changing the "scrum" to the "scrimmage," in which only one team's center was allowed to kick the ball back to his teammates (it took a couple of years before they figured out they could hike the ball better by hand). For Camp's scrimmage to work at all, he also had to invent the "line of scrimmage," with the teams set up on opposite sides and the ball in the middle. They tried Camp's brainchild in the 1880 season and the result was disastrous. Everybody but Princeton had forgotten that a weaker team could simply sit on the ball, run play after play and never kick, while playing for a tie. The Tigers showed this to Camp's strong Yale team and tied them, 0-0. In 1881, after a session back at the drawing board, Camp came up with the "downs-and-yards-to-go" idea. The mix sounds a little strange to modern ears - five forward or ten yards back (!) in three downs to get a first down - but it worked. From here on, the game ceased to be poor-man's rugby and became American football. A couple of years later, they started awarding different numbers of points for different actions: so many for field goals, so many for touchdowns, etc. Like the size of the field and the downs-to-yards ratio, it took them a while to get everything right, but by 1912 they had six points for a touchdown, three points for a field goal, ten yards in four downs for a first down, and a hundred yard field. They also had a legal forward pass.  The chain of events that eventually allowed the no-no pass to become a yes-yes began in 1887, when the rules makers decided to let defenders tackle ball carriers from the knees down, probably because players were doing it fairly often, by accident anyway. It didn't seem to be a big deal at the time, but ... the rulesmakers had unleashed a lot more than they ever intended. After Camp's yards-and-downs idea in '81, teams had continued playing a wide-open game - more premeditated than before, but still with backs spread out wide to take long pitches from the QB. As soon as the low tackle was legal, defenders started charging across the scrimmage line, diving at a halfback's feet, and cutting him down while the quarterback's pitch sailed who-knew-where. To counteract that, attackers moved everyone in tight, surrounded the ball carrier, and everyone churned forward like a human tank. And that's why the famous flying wedge and other grind-'em-out plays constituted the dominant style of offense in the 1890s. They might still run the wedge today except that in the '90s, more and more often a defense would suddenly realize that they only had ten men standing around waiting for the next onslaught. ... Finally, fans grew tired of seeing football players treated like grapes at Luigi's Winery. Even President Theodore Roosevelt bullied his way into the act, calling for reforms. The rules makers made up a whole passel of new rules in 1906, all aimed at getting rid of the wedge and opening the game up again. About the least important new rule at the time allowed forward passing, but they put so many restrictions on the maneuver that at first almost no one thought it was worth a darn. A Neglected Strategy Even when a couple of Notre Damers named Dorais and Rockne used the pass to beat Army in 1913, most coaches okayed it only in desperation - a sort of play of last resort. Twenty years after passing became legal, you'd have to scour the country to find a college team that threw more than half a dozen times during a game. Fans could give you details of important forward passes years afterward because they were that rare. Coaches, conservative old duffers that they were, had simply reinvented the flying wedge in the form of the single wing, a formation designed to get an abundance of blockers to a particular spot all at one time. Then, because college teams could practice-practice-practice, they'd run their off-tackle plunges and around-end sweeps over and over until their players could do them in their sleep. If you quarterbacked the ideal college football team in the '20s, you slugged away on the ground. Most teams knew what to expect and could put eleven decent players against you, so you seldom gained more than a couple of yards a try. Meanwhile, your punter kept your opponent bottled up at the other end of the field. Until you got inside your foe's 30-yard line, you might punt on third down - the most popular third-down alignment was a short punt formation which allowed some options - because you were almost as likely to fumble as to break away for a first down. Eventually, something gave - usually in the fourth quarter - and you scored a touchdown to humiliate your rival 6-0. It was football with the accent on "foot." Teams didn't so much win games as their opponents lost them by making a mistake. Coaches loved running because mistakes were less common, or at least less disastrous, on well-practiced runs than on somewhat ad-libbed passes - "putting the ball up for grabs" it was called. When a team lost with pass goofs, it got buried 20- or 30-0. Scratch a typical college coach in the '20s and you'd find someone who'd rather be certain of losing 6-0 on the ground than take a chance of winning through the air. 1908 - 1947: The Great Interregnum Auburn vs Alabama: Gridiron Grudge Since 1893, John Chandler Griffin (2001)

For nearly 100 years fans have wondered just what occurred in 1908 to cause a 41-year disruption in the Alabama-Auburn football series. And even today most of the facts are still somewhat confusing.

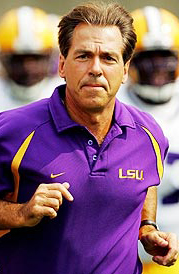

Back in 1907 it had been mutually agreed between Alabama and Auburn that visiting teams would be paid $2.00 per player for 17 players to cover both their hotel rooms and meals for two days. The total cost: $68. But on January 23, 1908, Alabama coach J.W. Pollard received a proposed contract from Auburn football manager Thomas Bragg requesting $3.50 per man for 22 players. The total cost would be $154 for two days of lodging and meals. Bragg further requested that the game be played on November 14 at the Birmingham Fair Grounds. After reviewing the contact, on February 24 Alabama sent Bragg a compromise contract, proposing that Auburn be paid $3.00 per day for two days for 20 players, a total payment of $120. But Bragg returned the proposal, stating that Auburn could not agree to a reduction in the per diem rate or the number of players outlined in his original proposal. Bragg also mentioned that Auburn was not happy with Alabama suggestions for selecting referees for their 1908 football game, and that Auburn demanded that the referees be Northerners. At any rate, he continued, Auburn would offer more definite suggestions by April 1. By April 6, having received no further communications from Auburn, Alabama again contacted Bragg. But Bragg responded that questions concerning the officiating of the game could not be decided until after Alabama had signed and returned the contract Bragg had sent to them back on January 23. He stated once again that Auburn insisted on bringing 22 players to the game and that they be paid $3.50 per man per day. Following receipt of this letter, on April 24, Alabama's Executive Committee on Athletics, ignoring the response they'd just received from Bragg, drew up a new contract. This one was identical to the one they'd sent Bragg back on February 24, offering $3.00 per diem for 20 players. They also insisted that Southern officials should referee the game.   L: Alabama coach J. W. Pollard, R: Auburn coach Mike Donahue The next day, April 25, Auburn coach Mike Donahue and Bragg met with Alabama officials, a Mr. Pritchard and Coach Pollard, in the lobby of the McLester Hotel in Tuscaloosa. At that meeting Coach Donahue expressed his view that "there was not a man in the South of sufficient ability to act as umpire in intercollegiate contests." Alabama strongly disagreed and pointed out that it would cost a minimum of $250 to bring down a referee from north of the Mason-Dixie line, and that such an expenditure was unnecessary. But Auburn refused to budge on the question of referees. They also repeated their demand that they be allowed to bring 22 players to the game and that they be paid $3.50 per player, as called for in the contract of January 23. The Tuscaloosa Times-Gazette reported that "Auburn's refusal to entertain any of Alabama's suggestions made it evident that a compromise was impossible, so the discussion was closed." By May 17 the Montgomery Advertiser, under the headline "Auburn Side Is Presented," reported that statements made recently by representatives of the University of Alabama in the Birmingham Age-Herald were "so inaccurate that they cannot be allowed to pass unanswered." The Advertiser then quoted Manager Bragg as stating that, rather than create any controversy, he had accepted a contract from Alabama in 1907, the previous year, which granted only $2 per player. He pointed out to Coach Pollard that $2 per man really wouldn't meet Auburn's expenses, and that Pollard assured him that "we will make this up in our 1908 contract." Bragg went on to state that "the 1907 contract occasioned a loss of from $1.50 to $1.75 per man for two days, and while this was an absolutely necessary and legitimate expense, it had to be paid out of Auburn's share of the proceeds of the game." Bragg stated that he had informed Pollard, both verbally and by letter, that he would be willing to take $3.50 as the maximum rate, but if it turned out that the team's expenses amounted to less, then Auburn would charge only the amount actually incurred and would return any unused money to Alabama. As for the referee question, Bragg was quoted as saying, "With regard to the committee's assertion that Mr. Donahue and I stated that there was no man in the South capable of umpiring an intercollegiate contest, I would emphatically deny that we made any such statement. We simply stated that we did not know of a satisfactory available man to officiate as umpire in the Alabama-Auburn game, and we asked Dr. Pollard to suggest some men for our consideration, though he failed to do so. Moreover, we did not ask that an Eastern man be selected as umpire until after we had failed to agree upon some available Southern men." The resolutions sent to the Auburn management were in the nature of an ultimatum, dictating the only terms upon which the Alabama authorities would sign a contract for next season, and using as a threat the statement that negotiations were being opened with other colleges for a game on November 14, before the Auburn authorities had had the opportunity to finally pass upon the matter. Two days later, on May 19, the Birmingham Age-Herald, in a fine example of slanted journalism, reported the following: "Auburn's action in this matter is indicative of a desire to evade its annual game with Alabama. Alumni of both institutions in Birmingham think that the talk of an Eastern umpire is ridiculous. The people regret that Alabama and Auburn will not meet this year. They care very little for the reasons." The series would not resume until 1948. Game Changer: Red Grange

Football Nation: Four Hundred Years of America's Game from the Library of Congress, Susan Reyburn (2013) Football's strategic complexity makes it difficult for the fortunes of an entire team to hinge on the efforts of a single player. However, the success of an entire football league can be attributed to one man, Harold "Red' Grange. The ever-grateful New York Giants owner Tim Mara would never have built his football dynasty were it not for the ice deliveryman from Wheaton, Illinois. And Grange did not even play on his team.

Grange took all of twelve minutes to become a football legend. On October 18, 1924, a Michigan team that had given up only four touchdowns during its 20-game unbeaten streak rolled into Champaign, Illinois, looking for number 21. They ran into or, rather, were outrun by, number 77. Students of football know the stats: In the first quarter alone, the flame-haired Illinois HB scored four TDs on runs of 95, 67, 56, and 45y; he later ran for another score and tossed a TD pass as the Illini won, 39-14. While that was his single greatest performance, as a three-time All-American he regularly produced eye-popping numbers that left reporters rummaging through their Roget's for words to describe him. Grantland Rice called him a "rubber bounding blasting soul," whatever that was, and Paul Gallico referred to him as a "touchdown factory." Dubbed "the distinguished ice peddler" and "pigskin purveyor," his lasting nickname was "Galloping Ghost" for his quickness and shifty moves. Grange made up for his unimposing size (5'11" tall, 175 pounds) on trailblazing end runs, dispatching would-be tacklers with a straight-arm sculpted from hauling around 75-pound blocks of ice.  Red Grange totes the pigskin for Illinois.

Grange's immense talent, however, is not the fundamental reason for his hallowed place in football history, which, because he got there first, no one else can rival.

When Grange played his last college game in November 1925, the pro sport was on thin ice and losing money. Who better, then, than a man of Grange's stature to shore up the league before it melted away entirely? The thing was, few exceptional college players were in the National Football League; professional players were about as respectable as actors in Shakespeare's era and sometimes paid even less. There was a discomfiting sketchiness to the NFL. Grange, however, questioned that. "You coach for money," he told his college coach, Robert Zuppke. "Why isn't it okay for me to play for money?" Zup was not amused. Grange's decision to play in a Chicago Bears game five days after Illinois's season ended was shocking, yet it had exactly the effect the NFL hoped: It prompted a second look at what professional football could be. But the Ghost's decision did not go down well with those closest to him. "My coach, Bob Zuppke, didn't talk to me for four years. My father wasn't happy about it," Grange said later. "All of my friends looked upon me as if I was a traitor or something, as if I had done something terrible." At the time, good players might make $100 a game; most scraped by on less. His manager-agent, the enterprising but not always law-abiding C.C. Pyle, arranged for himself and Chicago Bears to split the gate fifty-fifty with Chicago Bears owner George Halas. It was an astonishing contract, matched only by the audacious and brutal schedule Pyle and Halas organized for the Bears. From late November 1925 to late January 1926, the Bears toured the country, playing 19 games, and Grange was in all but two. In his first outing, he filled Cubs Park (Wrigley Field), drawing six times the usual gate. When he showed up at the Polo Grounds, so did more than 70,000 spectators, one of whom was Babe Ruth, sitting at midfield. Eying the crush of news media that greeted Grange, the Yankee slugger quipped, "I'll have to sue that bum. They're my photographers." Tim Mara probably did not mind that his Giants lost that day. The team, which he had recently purchased for $500 and now wanted to sell, had already put him $45,000 in the hole. In a single afternoon, though, Grange single-handedly filled the stadium and sent Mara home $130,000 richer. The Bears' blitz and Grange's presence gave professional football a sense of legitimacy among fans, and it demonstrated to potential club owners that, with the right personnel, the NFL could be a profitable venture. Grange's success inspired other college stars to join the NFL, which dramatically improved the quality of professional play. Without Grange pulling in huge crowds everywhere he went, the tottering NFL might have gone the route of every other short-lived pro leage that preceded it. Despite injuries that made much of his nine-year professional career painful, Grange carried on, earning a place in both the college and professional football halls of fame. No better than George Halas, the last surviving founder of the NFL, put Grange's impact on the league in perspective when he said that "Grange was to us then what television is to the modern era." At the time, he was the best thing the NFL had to sell itself. Fatso Stories

Fatso: Football When Men Were Really Men, Arthur Donovan Jr. and Bob Drury (1987)

Art "Fatso" Donovan played DT for the Baltimore Colts from 1953-61.

Once, we were flying home from the West Coast after a win over the Rams in 1959. But first we had to wait four hours for the plane, and of course we all waited in the airport bar. The jet finally arrived, and since our famous coach, Weeb Ewbank, was too cheap to stock our flights with booze, we carried on our own. All of us had beer, except for Big Daddy Lipscomb, who was to wind up dead of an overdose a few years later. Big Daddy liked his VO, and he came strolling down the aisle of our plane with two fifths of whiskey.

We drank all the way back to Baltimore, and by the time we landed, the sun was up and everybody on the plane had a vicious hangover. Everybody piled off the plane in various states of drunken dishevelment except for our tight end, Jim Mutscheller, who halfway down the ramp decided he had to use the head on the jet because he couldn't make it the couple of hundred yards to the airport. The plane was refueling for the trip back to Los Angeles when Mutsch opened the door to the head, and who was sitting on the throne, passed out, but Big Daddy. He had his two fifths of VO, empty, cradled in his arms like babies. They would have flown back West with Big Daddy on that throne if Mutsch could have held his water another five minutes.

L-R: Art Donovan, Weeb Ewbank, Big Daddy Lipscomb

One of the best flights we ever had was after a loss in Detroit. Nobody was too happy to begin with, because we should have beaten those guys, and by the time we boarded the flight, half the team had a major-league package on. It didn't take long for the other half to catch up. And up at around twenty-five thousand feet a huge brawl broke out between the offense and the defense. They were gouging and biting and blaming each other for the loss. Well, I was one of the guys trying to break up the fight but having no luck at all. Meanwhile, the plane was pitching back and forth as these behemoths were throwing each other all over the goddamn cabin. Weeb wouldn't get out of his seat because he was afraid somebody was going to throw him out the window.

Finally, the pilot got on the intercom and announced that if we didn't stop, he was going to have to make an emergency landing and we were all going to jail for air piracy or something like that. That was the only way to stop them. They were crazy animals. And Weeb never said a word throughout the whole trip. Through my first four years in the league, before Weeb took over the Colts in 1954, I played at six-two, three hundred pounds. I was a light eater. When it got light I started eating. I had a bit part in a movie Two for the Money and when the wardrobe people asked me my clothes sizes they told them to check with Omar the Tentmaker. They used to weigh me on a scale downtown at a grain store. But after Weeb came in, I always had a clause in my contract stating I had to play at 270. They weighed me in once a week, and what a show that would be. I'd step on the scale, it would register something like 275. I'd take off my sweat shirt and drop two pounds. My pants would be another pound and a half. And I'd get down to 270 and a half by dropping my underwear. Just when everyone thought I'd be fined for coming in a half pound overweight, I'd pull the coup de grace and take out my false teeth. Everything went fine until 1959. Toward the end of the season, the Colts were on the West Coast to play San Francisco and Los Angeles. We had to win both games to take the division title. We beat the 49ers and stayed in San Francisco to practice, and that was a big mistake. How can you not gain weight in San Francisco? My tonnage shot to 280. Weeb was so preoccupied with the Rams game that he didn't have a team weigh-in beforehand. He only weighed a guy named George Preas and myself. ... I had a $2,000 bonus clause in my contract. I'd collect if I stayed at 270 all season. Here we were in the last game of the year, and I had blown it. After he weighed me, I went up to Weeb and asked him about a deal. "Suppose I have a good Rams game," I said. His answer: "I'll talk to you about it after the game." Anyhow it was about 110 degrees in L.A. by game time. Big Daddy begged out with a bad ankle, although I honestly believe he just didn't feel like playing in that heat, and I had to play the whole game. I was dying. Late in the game, with about three or four minutes left, we were murdering them by about five touchdowns. The Rams finally put in their rookie quarterback, a guy by the name of Frank Ryan, who went on to become a star with the Cleveland Browns ... I said to myself, "Thank God," because I was sure he had been sent in to run the clock. But no. This guy Ryan got the ball and started running all over the field and throwing bombs. And I was chasing him and screaming at him and calling him all kinds of names. I yelled at him, "I'm gonna kill you when I get you!" But, truth be told, I couldn't have caught him if he was crawling on his hands and knees. So I finally figured the hell with this, and went over to the Rams huddle and said to this guy, "Listen, rook ... Give up the ghost. Run out the goddamn clock." And he just calmly looked up at me and said, "Drop dead, you big, fat SOB." I was shocked. Stunned. I wanted to kill him. Suddenly I realized my teammate Ordell Braase was yelling at me, "Hey, Fatso, you're in the wrong goddamn huddle!" And sure enough, the refs penalized us five yards for being offside. When the game ended I crawled off the field and went looking for Weeb. I wanted to ask him about my money. "Hey, Weeb, ... I guess I'm going to get my two thousand dollars back now that we won the game and everything." "Hell, no, Donovan," he said to me. "You don't get nothing 'cause you're out of shape." I asked him what the hell he was talking about. After all, I had played the whole game in stifling heat. And that rat bastard told me that if I was in shape I would have caught Ryan and ended the game that much earlier. I never got the money, either. Legend: Bo Jackson

SEC Football's Greatest Games, Alex Martin Smith (2018)

The greatest player in Auburn history grew up a huge Alabama Crimson Tide fan.

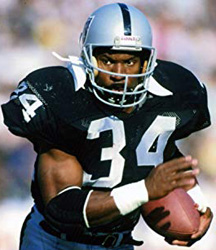

Who knows? Bo Jackson might have led the Tide to a national title in Bear Bryant's final season, but there was one major snag: the Bear didn't like playing freshmen. And not even a scary-good athlete such as Jackson was going to see the field early. Aside from his career as a two-way gridiron destroyer and a non-hitter-tossing pitcher, Jackson was a two-time Alabama state champion in the decathlon at McAdory High in small-town McCalla. There was likely some skepticism about his ability to be a star running back in the SEC, but there were no doubts about his superior athleticism. As Bryant's health slipped, Pat Dye's staff pounced: ... Paul Finebaum recalled Auburn assistants mailing copies of unflattering Bryant photos ("he just looked terribly old") to every Tigers recruit. In person, they had a simple pitch for Jackson: If you're the best running back we have, you'll play. Whatever the primary reason, Jackson spurned his childhood team and drove to Lee County to begin his college football career. Unlike Georgia's Herschel Walker, who mostly failed to meet expectations during his first Georgia camp, Jackson was electrifying from the outset. "I turned around to hand him the ball, and he was already gone past me," QB Randy Campbell recalled. "I told the coaches, 'He's lining up too close.'" He wasn't. And he made a swift climb to the top of the depth chart.    Bo Jackson Auburn Tiger, Oakland Raider, Kansas City Royal "The thing is, he was so much better than everybody," Campbell said. "Nobody went back to their rooms saying, 'I can't believe they put that freshman ahead of me.' ..."

Jackson helped Auburn reclaim Yellowhammer bragging rights afer a long period under the Crimson Tide's thumb. It seemed he save some of his wildest moments for the Iron Bowl; Auburn fans still smile upon hearing the phrase "Bo Over the Top," just as their faces get cloudy at mention of "Wrong Way Bo" (a critical missed blocking assignment in '83) or "the Kick" (a game-winning FG that nullified Jackson's two TDs on cracked ribs in '84). There was also a Sugar Bowl win over Michigan and the 1985 Heisman Trophy. But football wasn't Jackson's only love at Auburn. He also starred on the baseball diamond, where he batted .401 as a junior and collected 28 career home runs. "Bo was without question the most incredible specimen I have ever seen in virtually every measurable physical category - speed, strength, eye-hand coordination, leaping ability, arm strength," baseball coach Hal Baird said. "You name it, Bo was off the charts." Following his time at Auburn, he was a two-sport professional star, becoming the first - and still only - athlete to be named both an MLB all-star and an NFL Pro Bowler. His freak athletic ability resulted in too many iconic moments to cover here. Among them: a lightspeed 91-yard TD run on Monday Night Football, a baseball bat snapping in half across his knee, and a Spider-Man-esque outfield wall climb after sprinting to make a catch. All of it took on mythical status. He became a pop-culture sensation. Nike ads insisted "BO KNOWS." Tecmo Bowl turned him into the Incredible Hulk, and he did his best real-life impression on Sundays. Though his football career ended prematurely after a 1991 hip injury, his legend lives on across the world. "I loved being better than the next guy," he said in 2017. "I enjoyed watching people's eyes jump out of their heads watching me do something that was normal to me." Major Mistake?

Montana: The Biography of Football's Joe Cool, by Keith Dunnavant (2015)

Several of the athletes who played significant roles in one or both Super Bowls were entering the end of their careers ... but perhaps the most difficult transition involved receiver Freddie Solomon, a popular and high-profile player who had been instrumental in San Francisco's rise to the top of professional football. Nagging injuries and the unyielding calendar had convinced [head coach Bill] Walsh that Solomon's best days were behind him, so as he approached the 1985 draft, finding another talented receiver for Montana loomed large in his plans.

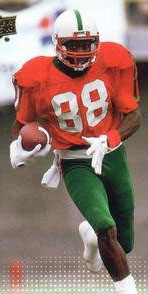

The solution to this particular problem first presented itself in 1984, on a road trip to play the Houston Oilers. Relaxing in his hotel room on the night before the game, Walsh happened upon a local television sportscast featuring highlights from a small college game way off the football map. Narrating one long pass play after another, the anchor made no attempt to conceal his amazement. Jerry Rice was that good. Somehow ignored by the nation's major colleges, the brickmason's son with the reserved bearing and the sort of perfectionist streak that so often drives greatness, wound up at tiny Mississippi Valley State, a small, historically black school with an enrollment of less than three thousand. Because the competition he faced in the Division 1-AA Southwestern Athletic Conference was far below big-time college football, NFL scouts and coaches looked upon his statistics with skepticism. But after catching an NCAA-record 112 passes for 1,845 yards and 27 touchdowns as a senior in 1984 - teaming with QB Willie Totten, who led a potent attack that averaged a stunning 59 points per game - Rice could not be easily ignored. Most teams projected him to last until at least the third round, but Walsh was not prepared to take such a chance. Despite significant opposition from his scouting operation, he paid a high price - much higher than some thought prudent - to acquire Rice: trading three draft picks to procure the seventeenth overall selection in the first round, which he used to take the player who would become one of the cornerstones of the franchise. Then he started pushing Solomon toward the door.

L-R: Bill Walsh, Freddie Solomon, Jerry Rice

By this time, defenses were employing various tactics to try to counter Walsh's ball-control passing game. One of the most effective was the advent of man-to-man coverage on the short and intermediate routes, which made it imperative that the 49ers feature a wide receiver who could stretch the defense vertically. Not only would this give Montana significant options downfield, the requirements of protecting against such a threat would leave the defense even more vulnerable to the 49ers' pass-catching backs, especially Roger Craig. Watching him in action, Walsh believed Rice could prove to be such a transcendent force for his offense.

The transition proved bumpy. As San Francisco opened the 1985 season with a loss to Minnesota and a victory over division rival Atlanta, Rice stunned teammates and coaches with his deceptive speed and a knack for getting open, but his hands suddenly betrayed him. Time after time, he dropped perfectly thrown passes. "[Joe] didn't say it, but you could tell that he was starting to have doubts," Rice remembered. Trying to be patient, Montana could see "he was trying too hard. You try so hard and when you screw up, you think everybody's looking at you, thinking how you don't belong - even if they're not." Montana and other teammates tried to soften the blow, but many San Francisco fans were not so understanding, filling Candlestick with cascading boos when the man who once had been nicknamed "World" - because there was no pass in the world he couldn't catch - let another ball slip inexplicably through his fingertips. ... In the lone loss during the stretch [of five victories over a six-week span], one aspect of the Niners' future began to emerge: Jerry Rice found his hands. After weeks of struggling to live up to the potential Walsh and the other coaches saw in him, Rice caught 10 of Montana's passes for 241y, including a 66-yarder. The breakout game marked the unofficial start of one of the greatest batteries in football history. How the SEC Became Goliath, Ray Glier (2012)

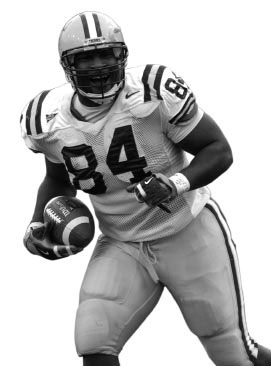

There was a fringe benefit of playing for LSU coach Nick Saban, something valuable to a couple of his players in addition to winning games and getting trained for the NFL. The coach had a pond with fish and he seemed much too busy to snatch those fish out of the water himself. So Mike Clayton, an LSU wide receiver, and Marcus Spears, an LSU defensive end, would make their way around the back of Saban's big house on Highland Road in Baton Rouge and drop lines into the coach's pond and fish. ...

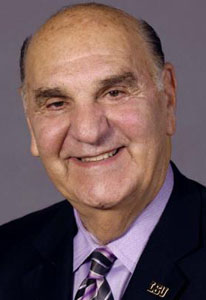

Clayton was from south Baton Rouge and Spears was from the Bottom, a poorer area of Baton Rouge, and the idea of fishing at the manor of an LSU coach seemed so preposterous if you understood the history between south Baton Rouge, the Bottom, and LSU. Clayton and Spears would never have fished in the pond of an LSU football coach before 2000. Peed in it? Yes, they would have done that. LSU was mistrusted in some parts of town. The football coach represented a hierarchy at LSU that did not blend with south Baton Rouge, Clayton said. The coaches were not racist, but their hands seemed tied by politics. Was it accurate? Were there politics? It doesn't matter. That's the way the Claytons ... saw it and that's what mattered. When LSU coach Gerry DiNardo, who was regarded as a skilled recruiter, did not show any interest in recruiting Mike Clayton, a star WR from south Baton Rouge, the rift between the neighborhood and the LSU campus grew wider. The Claytons had issues with the politics at LSU, which is to say they thought a good-old-boy element still lurked there when Mike was met with a cold shoulder by DiNardo. If Florida State and Bobby Bowden could recruit him hard, why couldn't his hometown school? The Claytons thought the worst of LSU.    L-R: Michael Clayton, Marcus Spears, Nick Saban Clayton, who attended Christian Life Academy, already had his bag half packed for Florida State. The heck with LSU. The kids from the Bottom or south Baton Rouge never thought they got a fair shake at LSU, so they were always looking elsewhere first, Clayton said. "I never got one letter until Saban and his staff got on campus," Clayton said. "Jimbo [Fisher] would come watch me play basketball, and I would show off for him." The Claytons let Saban in the front door. "The neighborhood was going, 'What are you doing talkin' to LSU? You know how things can go there,'" Clayton said. "A lot of guys just went to Alcorn, or one of the other HBCUs. We saw too many of our guys go to LSU and then transfer." Saban, who was in his first season as head coach at LSU, made his pitch to the Claytons. He was earnest, like a man selling Bibles out of the trunk of his car. He talked about college being a forty-year decision, not a four-year decision. He talked about life after football. You could go to your hometown school and come back after the NFL and own shares in a bank, own a clothing store, own real estate. There would be roots. When the coach was finished vending LSU, Milton Clayton, Mike's father, tried to put his feelings in a gentlemanly sort of way to Saban: "There are politics at LSU, Coach. Things go on. Sometimes the best players don't play." "There will be no politics," Saban said. "Not as long as I'm here." Well, how many coaches had said that before only to let politics creep into the locker room, into the meeting room, into the coach's ear? A kid from the South Baton Rouge Rams, among the elite of the Pop Warner football programs, was just asking to be trashed if he believed this blather. "Don't be sorry, Mike," some of the neighbors told him. "Go to Florida State, go to Miami, go anyplace but there." Years of mistrust were barking back at Clayton, and perceptions are hard to tear down. LSU had been one of the last SEC schools to embrace black players. The Claytons were not indicting the whole campus, but they were suspicious, as black folks have learned with justification to be suspicious. Many LSU fans will likely scoff at Clayton's assertion that as late as 2000 racial prejudices affected the makeup of the Tigers' rosters. Clayton scoffs back a those who think sports is color-blind and that winning overrides all racism. "Just the other day I'm on the golf course in Tampa, and this white guy rolls by in his cart and says to his friend, 'Hey, look at that nigger playing golf,'" Clayton said. "That's the day we still live in. Some people look at color. It's still not gone." ... Clayton scratched Miami off his recruiting list because on his visit there with Spears ..., they found South Beach too raucous and too tempting. "All kinds of stuff was going on there," Clayton said." There was still time to decide before the February 8 signing date, but Clayton thought maybe he should give Saban a chance. Clayton liked Saban, the son of a gasoline-station operator from West Virginia. Florida State was still Clayton's top choice, but a window had opened for LSU, or was it a hole opening in a fence that had been built up between a neighborhood and a school? On the night of December 29, 2000, Clayton and Spears ... were sitting in a restaurant in Dallas before they were to play in a high school all-American game. On the restaurant's television, LSU was playing Georgia Tech in the Chick-fil-A Bowl in Atlanta. A black QB, not a white QB, flashed across the screen and was making plays. Rohan Davey was taking snaps ahead of Josh Booty, the white QB, a Louisiana legend from Evangel Christian. Davey led the Tigers to a win with a strong second-half performance. Clayton and Spears looked at each other. "What just happened?" Maybe Saban could override the politics, after all. A black QB was allowed to be the star of the game they were watching on TV. It had happened before at LSU with Herb Tyler (1995-98), a black QB who shone, but Clayton saw a black QB in competition with a white QB. The black QB scooted ahead; he was allowed to scoot ahead. In the Dallas restaurant, the Baton Rouge boys starteds doing something preposterous. They started recruiting for LSU. A south Baton Rouge kid and a kid from the Bottom, who would have stuck their fingers in a light socket before selling for LSU, became salesmen for the Tigers. Perhaps the place wasn't so bad at all. They worked on the high school players in Dallas at the all-star game who had still not made up their minds where to go to college. In all, Clayton said, six players in that game went to LSU. "He meant what he said about there not being politics anymore," Clayton said of Saban. "You could tell on the television that night. What Rohan did changed some people's minds." Spears flipped to LSU. ... "It was, who is your daddy? Who did your daddy play for? How much money did they give?" said Spears. "Nick got there and he could have cared less whose daddy played there." ... In 2003, LSU (13-1) won a national championship. That 2001 class - headlined by Clayton and Spears, two Baton Rouge stars who had sworn they would not play for the Tigers - was the core of the first LSU team to win a title since 1958. James Moran, Tiger Rag, November 4, 2014

Skip Bertman knows how to keep a secret. In fall 2004, Bertman was asked to keep an atomic bomb of a secret quiet, and for a month the then-LSU athletic director was able to keep it tucked securely under his purple and gold hat.

Nick Saban had received an offer from an NFL franchise during each of his first four seasons as the head coach of the Fighting Tigers. He always called his athletic director to inform him of each overture, per a stipulationin his contract, and Bertman never considered them to be anything more than a bargaining chip. Saban had held a press conference to turn down a head coaching offer from the Chicago Bears that January, and he had fended off advances from the Jacksonville Jaguars, Pittsburgh Steelers, and other franchises in the years before. This time was different. Owner Wayne Huizenga badly wanted Saban to run his Miami Dolphins, and with a multi-billion dollar bankroll at his disposal, he was willing to do whatever it took to get his man. "Nick really didn't want to go," Bertman recalled. "He and his wife Terry loved it here, and he had a great team coming back. My God, he had about 80 people coming back. But every time he went back and asked Huizenga for more to try to get out of the deal, Huizenga responded." It wasn't just a matter of money - though he received plenty of that. Saban asked for complete control of the coaching staff, the training staff and even player personnel. He asked for everything short of a minority stake in the franchise and the kitchen sink, and to it all Huizenga said yes. On an unseasonably warm fall morning, Saban walked into Bertman's office and dropped the bomb that all LSU fans feared would one day come. The coach who had delivered the program its first national championship in nearly half a century was gone. He had bigger fish to fry. "He walked in and said to me, 'Can you keep this quiet, but I got to go because if I don't take this offer I'll never get another one,'" Bertman said. "He figured if it didn't work out he could always go back to coaching college football." "In the back of his mind I think he always knew it would be a difficult place for him to coach. He knew guys like Steve Spurrier that weren't able to do it, but he wanted to give it a try. You can't blame him for that." To this day Saban's contract and overall package remain the largest ever given to a college coach heading to the pros.   L-R: Skip Bertman, Wayne Huizenga, Nick Saban Of course that was easier at a time before Twitter and camera phones, but aside from sporadic reports of Huizenga's personal jet being sighted in Baton Rouge, Bertman did just that. ... Saban asked that he be allowed to announce his own departure after the Capital One Bowl on New Year's Day. Bertman had already given his friend a month of silence - a moratorium that cost LSU a chance at going after Spurrier or Urban Meyer - and he couldn't wait any longer to go public. It broke on Christmas day: Saban to Miami was a done deal. ... Bertman had the inside scoop to avoid surprise when news of Saban's departure got out. His players were not so lucky. The hundred-or-so young men that Saban had recruited and coached for the previous years were blindsided with just a week to gather their thoughts and emotions before taking the field against Iowa in Orlando FL. ... But the hatred LSU fans now hold toward Saban isn't because he took Huizenga's money and ran or even because he left his players high and dry to do it. ... Most Tiger fans genuinely wished him well as he rode off into the South Florida sunset. That changed two years later, of course. After banging his head against the wall toiling in NFL mediocrity, Saban did exactly what he told Bertman he would do should the Dolphins move not work. Saban issued repeated denials, but on Jan. 3, 2007 ... he announced he'd be leaving the Dolphins to become the 27th head coach of the Alabama Crimson Tide. It was at that moment that LSU fans realized that their worst fear wasn't losing Saban, but rather his returning to the SEC. He's been public enemy No. 1 in these here parts ever since. The More You Can Do ... Taysom Hill

New Orleans Saints Gameday, August 9, 2019

It would be fair to say that Taysom Hill is a "do-it-all" QB for the Saints. But that doesn't necessarily begin to cover one of the most interesting stories in the NFL.

Hill's story began in Pocatello, Idaho where he played QB for Highland High School and was the All-Idaho Player of the Year, Gatorade High School Player of the Year and first-team all-state selection in 2009. Hill received offers from many schools in the West including Arizona, Boise State, Washington State, Stanford and BYU. He ended up committing to Stanford under then-coach Jim Harbaugh but never actually landed on campus. Instead, he decided to fulfill a two-year Mormon mission trip in Australia. ... When Hill completed the trip, he decided to return home and jump back into his football career at BYU, where the football program was more familiar with athletes serving mission trips than most programs. ... By his junior season at BYU, Hill was a Heisman Trophy candidate with the likes of Marcus Mariota and Jameis Winston - both are now starting NFL QBs. That season, however, was cut short due to an injury. That was all too familiar for Hill, as four of his five seasons at BYU ended in injuries - a knee injury, a broken fibula, a foot fracture and an elbow strain. What got Hill through all those injuries? ... Hill would go back to advice he received from Harbaugh, who he stayed in contact with after the recruiting process. "He shared with me an experience that he had when he was playing at Michigan where he had just broken his arm his junior year and wasn't able to play and compete," Hill said. Harbaugh told Hill that the best way to fill the void of not being able to play football was to compete in something else. "I went and competed in the classroom," Hill said. "That filled the void mentally and emotionally of where I was feeling like I was still contributing to Taysom Hill the person, as well as rehabbing and getting back and ready for the next season, which was also contributing to Taysom Hill the football player. ..." Hill ended up graduating from BYU with a degree in finance. ...    L-R: Taysom Hill with BYU and Saints and blocking punt against Bucs The Packers brought Hill to training camp in 2017 as an undrafted free agent. The coaches quickly liked what they saw and planned to sign him to their practice squad after preseason. Meanwhile, Sean Payton had been studying film on Green Bay WR Max McCaffery. He then noticed the person that was throwing the ball to McCaffery. He was intrigued.

Not too long after that, the Saints picked up Hill off of waivers and he was in New Orleans. "There was no grace period," Hill said. He found out that Saturday that the Saints had picked him up, he flew to New Orleans on Sunday and was out practicing on Monday before the 2017 regular season opener against the Vikings. His experience in New Orleans was culture shock compared to what he was used to in Idaho. But one thing stood out to him: "The city was unique, the people were unique and I felt the love for the Saints the second that I got to New Orleans," he said. Hill was trying to learn as much as he could from QBs Drew Brees and Chase Daniel ... "I was just trying to do the best I could and trying to catch up and learn the system," Hill said. ... Hill's career took a fascinating turn late in the 2017 season when then-Special Teams Coach Mike Westhoff needed a player to cover kick returns. Hill was that guy. In his career up to that point, Hill had done a lot of things. In high school he played WR, RB while also serving as the punter/kicker. Hill grew up a multi-sport athlete. He ran track, competing in the long jump and 200-meter run. But covering a kickoff in the NFL? That was a new one. "When the special teams coaches came to me and they had this experiment of putting me on special teams, it was a whole other ballgame where I went through that experience all over again of trying to learn a new system and new positions that were so foreign to me," Hill said. Hill worked with secondary coach Aaron Glenn on tackling drills, all while still wearing his red non-contact jersey, the week before he would take his first shot at playing special teams. In his NFL regular season debut against the Panthers, Hill picked up two tackles and came close to blocking two punts. Payton gave Hill the special teams game ball following the win. Payton continued to new ways to use Hill last season, which his stat line attests to: 3-for-7 passing with 64y, 37 rushing attempts for 196y, three receptions, 14 kick returns for 348y, six special teams stops and a blocked punt. His first kick return was a 47-yarder against the Browns. The following week against the Falcons, he returned three kicks for 64y, made a tackle on special teams, was used as a TE to block and even ran the ball three times for 39y. Hill scored his first TD against the Redskins ... Hill picked up the NFC Special Teams Player of the Week honor when he blocked a punt against the Buccaneers that led to the Saints comeback victory and clinched the division title. He was also a key part in the Saints NFC Divisional Playoff win against the Eagles. New Orleans was down by 14 points at the start of the second quarter when Payton called a fake punt on fourth down using the team's "secret weapon." Hill was able to get the first down, which ultimately sparked the comeback. During this year's training camp, Hill could still be seen practicing with special teams covering kicks and working on his tackling drills, but Payton is seeing his progress as a QB. Payton raves about Hill's abilities as a leader and a teammate and says his grasp of the offense is continuing to increase. For now, Hill will take any opportunity he can to get on the field. He might not have the starting QB position that he would like, but he's still been able to compete and throw himself in a role where he is successful. ... "I had zero expectation that my career would go this way in the NFL," Hill said. ... I've always been a competitor. I've always loved being on the field and competing. I have had so much fun being able to get on the field, be in the huddle with Drew ... And it's been a really unique experience." So, what exactly is Hill? You could call him a "do-it-all" player. Maybe even a swiss-army-knife type of guy. I would be fair to call him all those things. To Hill, he is and always will just be a QB. "It's really been a fun experience for me," Hill said. "I couldn't ask for anything more." Of Locks and Lore

David M. Hall and Alexander Wells, ESPN the Magazine, Sept. 2019

Jeremy and Amanda Lawrence had two boys. Chase was older, the artist. Trevor, the athlete, came five years later. By the time Trevor was 3, he spent Saturdays in his dad's lap, crowded into an armchair to watch SEC football. The family, from Tennessee, treated Volunteers football as appointment television. As Trevor got older, Jeremy toted him to Neyland Stadium to see the Vols in person, after which Trevor took to the backyard to toss footballs and imagine he was Peyton Manning.

By fifth grade, Lawrence dodged peewee tacklers with a gangly brilliance. His grandfather dubbed him "Crazy Legs" Lawrence. By eighth grade, the family hired a QB trainer, Ron Veal, to work with Trevor during the offseason. By ninth grade, Clemson recruiting coordinator Brandon Streeter became a fixture at Lawrence's games. By 10th grade, every school in the country wanted a piece of Trevor Lawrence. In summer 2019, Lawrence finally met his childhood idol at the Manning Passing Academy. Duke coach David Cutcliffe, who mentored Manning in college at Tennessee, traded texts with his protege after the camp concluded. He wanted to know what Manning thought of the hotshot Clemson star, who beat Cutcliffe's Blue Devils 35-6 last season. "Well," Manning texted back, "he stared at me a lot." Miller Forristall should've been Cartersville High School's star QB, if not for this kid - this middle school kid - who showed up to spring ball in 2014 with eyes on the job. People were already buzzing about Lawrence, but Forristall wasn't buying the hype. "The kid's in eighth grade," Forristall thought. "How good could he be?" "I saw him throw one ball," Forristall says, "and I knew he was legit." Forristall switched positions. He became one of Lawrence's favorite targets and closest friends and eventually landed a scholarship to Alabama - where he plays TE. MaxPreps named Lawrence the nation's top freshman QB after the 2014 season, and his coach, Joey King, phoned Lawrence to deliver the news. The QB answered and King gushed. "Hey, Coach," Lawrence interrupted. "I'm in the middle of a video game. Can I call you back?" King was stunned. About 10 minutes later, King's phone buzzed. He picked up and blurted out the news again. "That's cool," Lawrence said. "So what are we doing in the weight room tomorrow?" Lawrence had suitors from across the country, but the toughest day of his recruitment occurred one afternoon during his junior season. Alabama coach Nick Saban was on the line, and a Cartersville team meeting was about to start. Michael Bail, Cartersville's QB coach, poked his head in on Lawrence and screamed at his QB to get off the phone. The team's own meeting had begun. What was Lawrence supposed to do here? "It's the only time I ever remember him being late for a meeting," Bail says. What Lawrence didn't know? Bail knew full well that Saban was on the phone. "Now I had him in an uncomfortable position," Bail says. Lawrence asked for another minute but still couldn't shake Saban, and when Bail returned for the second time, he acted like he wasn't interested in excuses. Lawrence was out of time. "OK, Coach, I've gotta go," Lawrence said into the phone, hanging up on the legendary Crimson Tide coach.   L-R: 6'6" Trevor Lawrence in high school and at Clemson Tony Dean was a senior receiver for Cartersville in 2016 and usually a reliable target. But during a regular-season game, he'd endured a brutal first half - a couple of drops, a fumble - in an otherwise forgettable game that Cartersville would eventually win easily. Dean was rattled.

Early in the third quarter, Lawrence had the offense humming. The Hurricanes drove into the red zone, and Lawrence took a shotgun snap, looking for a score. His first read was wide open in the back of the end zone. His second dragged across the middle, no defenders in sight. As pressure came up the middle, Lawrence rolled out to his right and sprinted toward the sideline. Just before stepping out of bounds, he unleashed a bullet past a couple of defenders and hit Dean, his third read, in the hands in the corner of the end zone for the touchdown. Lawrence trotted to the sideline, where Coach Bail was livid. What the heck was Lawrence looking at? "Coach," Lawrence said, "if we're making a playoff run, we need Tony. And Tony needed that catch today." It was a stiflingly hot Saturday in late August 2017, and the air conditioning inside Cartersville's locker room had been turned off. Saturday games were rare, but this was a nationally televised showdown between Lawrence's Hurricanes and Bartram Trail, a football behemoth from Florida. Lightning had the entire production on hold. Coaches, ADs and officials huddled to assess the situation while the players baked at their lockers, still in full uniform. During their meeting, Lawrence knocked on the door to request some Gatorade for the team. A few minutes later, it occurred to Bail that the coolers were still on the field, so he marched into the locker room. Inside, he found Lawrence hunched over a cooler, mixing up a vat of powdered energy drink. "Then he goes out and throws four touchdowns," Bail says. During one of Lawrence's first practices at Clemson in the spring of 2018 - he'd committed during his junior year at Cartersville - he rolled to his right and ran smack into a sack. In practice, QBs can be hit, but Christian Wilkins and Clelin Ferrell - the unquestioned team leaders, both ultimately first-round NFL draft picks - delivered the verbal equivalent, reminding the hotshot freshman that his hype didn't amount to squat here. "Christian was in his ear," says RB Darien Rencher. "I don't mean figuratively. He was literally yelling into Trevor's ear." Lawrence said nothing, just gathered the offense. On the next play, he rolled right again, but this time, before getting slapped by the rush, he unleashed a laser, across his body and 30 yards downfield - with no arc, Ferrell swears - finding the hands of his receiver. "I'd never seen nothing like that," Ferrell says. "I knew he had something special." Lawrence stared down his tormenters long enough to send a message, before celebrating the touchdown with the offense. "We were trying to break him," Ferrell says. "But he always stayed even-keeled." |