|

Alonzo Stagg - Hypocrite

Stagg vs. Yost: The Birth of Cutthroat Football, John Kryk (2015)

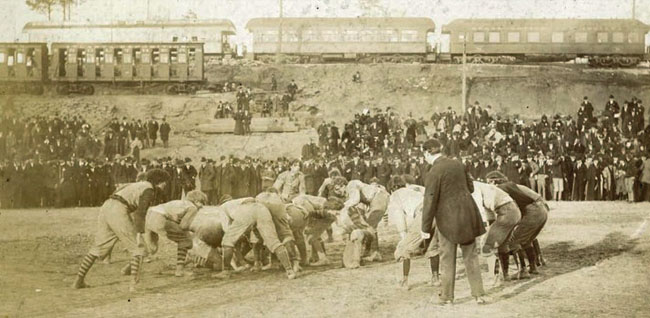

It was autumn 1894, and distrust soaked football relations between Wolverine athletic leaders and their counterparts at Oberlin College of Ohio. An officiating disagreement at the end of their 1892 game had led to each team claiming victory. Now, reps from the two wary sides haggled over the selection of officials for their coming November 17 game in Ann Arbor. ...

To break the stalemate, Oberlin's new football manager, Alvan W. Sherrill, suggested in a letter to his Michigan counterpart, Charles Baird, that they "leave it to Mr. Stagg to settle the affair of umpire." Namely, Amos Alonzo Stagg. In year three of his storied forty-year tenure as the University of Chicago's athletic direction and coach-of-everything, the 32-year-old Stagg already enjoyed a gleaming reputation as one of America's most incorruptible sportsmen. Michigan had been the first school to take up football in the West in 1879, and the Wolverines remained a perennial contender for regional honors. This year's team proved particularly powerful and knocked off Oberlin 14-6, a result closer than expected. As umpire, Stagg observed play amid the thick of the action. A week later, Stagg saw Michigan play again. He and two of his best University of Chicago players watched from the stands in Detroit as Michigan scored a landmark victory for a Western football team - 12-4 over Cornell, one of the upper-tier Eastern squads. Five days after that, on November 28, Stagg's Maroons played host to the Wolverines in their now annual Thanksgiving Day season closer in Chicago. The vastly undermanned Maroons gave the "Champions of the West" a surprisingly tight fight that day. Beyond the fact that the Wolverines' wounds from their clash with Cornell were still fresh, Michigan's offensive plays barely worked. Eventually, the Wolverines figured out why. Chicago knew their signals. The Wolverines released a statement after the game to the Chicago Inter Ocean daily in which UM athletic director Baird claimed that when his younger brother, wily Wolverine QB Jimmy Baird, barked out plays, "the Chicago captain would call out where to mass to meet the play, and this was done repeatedly." Later, the Michigan Alumnus magazine cut to the crux: "Stagg had secured our signals and made use of the knowledge, hoping to win the game by any means, however, questionable." Resorting to subterfuge such as lip-reading might be commonplace in 21st century sport, but securing an opponent's signals by any means in the 19th century amounted to sandalous, despicable form. The Michigan Daily student newspaper offered more proof: "Chicago claims she did not know the signals. ... It seems strange, then, that when the [Michigan] ends were called back and a signal given for a center play, Chicago massed her men on the center and paid no attention to the ends, where the position of the men would indicate that the play would go. Once, captain Beard purposely changed the signals three times, and each time Chicago massed to meet them." The Wolverines won 6-4 only when Jimmy Baird came up with this foxy antidote late in the game, near the Chicago goal line: he called an off-tackle play to the right for all to hear, but whispered to HB Gustave Ferbert to take the ball around the left end. That he did, for the winning TD - without any blocking and, according to the Michigan Daily, "without opposition," as the Maroons had massed on the opposite side to stop the called off-tackle play. ...

.jpg)  L-R: Amos Alonzo Stagg, Jimmy Baird The press and public ate it up. Dissenting voices eventually gave up. From the 1920s onward, Stagg's admirers and hagiographers always spit-polished this gem from his autobiography, which practically became synonymous with the coach himself: "I hate a man, a team, a school or a people who cheat. I should prefer to lose every game than win one unfairly." The historical record begs to differ, at least from 1892 to 1906 ... In the prime of his life, when Stagg's youthful competitive passions still raged, he in fact was as ruthless, as desperate, as conniving a victory seeker - and as shameless and creative a clandestine manipulator - as intercollegiate athletics has known. Stacking the deck became Stagg's modus operandi. The advantages he continually sought could be broad and systemic or subtle and minute - but always clever, seldom without plausible deniability, and sometimes even entirely legal. In a word, slick. Such as in the following incident from 1897, again involving UC's archrival, Michigan.

Alarmed Michigan authorities concluded that playing indoors would be an immense benefit to the Maroons, as booting placement field goals for any kicker, let alone Herschberger, could be done a lot easier indoors in calm conditions and on dry dirt, rather than outdoors potentially in the wind, or on wet or snowy grass - or mud. With the goalposts situated on the goal line back then, every time Chicago advanced the ball to the Wolverine 40y line, they'd be a threat to score. Michigan tried to move the game outdoors. Stagg would not budge. A Michigan alumnus rep in Chicago reported back to Ann Arbor that even though Stagg "admits freely the great advantage he has indoors," he denied that it had "any weight with him" in keeping the game at the Coliseum. Indeed, Stagg told the UM alum he had an "absolute indifference" to the advantage, "saying the game will not be won" by a Herschberger FG from placement. Stagg was right. The game was won by three Herschberger FGs from placement - one of which he booted from 45y out and at a severe angle. For the second straight year, Michigan scored more TDs than Chicago (2-1) but lost, this time 21-12. In those days, the team that scored more TDs almost always won. The next year, Michigan insisted the game against Chicago be held outdoors, and the Wolverines vanquished Herschberger and the Maroons on their UC field 12-11 to cap an undefeated season for the Wolverines and their first conference championship. Stagg's 1890s run-ins with Michigan were but an appetizer compared to the feast that lay ahead right after the turn of the century. Fielding H. Yost's arrival in Ann Arbor in 1901 as the new Wolverine head coach would jar Stagg as few events in his life ever did. Outlaw Football in Georgia!

Heisman: The Man behind the Trophy, John M. Heisman with Mark Schlabach (2012)

John Heisman was in his third year as coach at Auburn.

News of Von Gammon's death spread throughout the South quickly. Football programs at Georgia, Georgia Tech, and Mercer voluntarily disbanded, and Auburn's team did the same on November 2, 1897. Within days, the Georgia state legislature introduced a bill that would outlaw football playing in the state. A newspaper headline from the Atlanta Journal read "DEATH KNELL OF FOOTBALL," and the Atlanta Constitution reported, "the end of football playing in Georgia seems to be in sight. Its death knell has been sounded. The arch enemies of football have turned upon it, and from all sides come bitter denunciation of the game." A Georgia state representative introduced a resolution on November 1, 1897, that "the game of football should be prohibited from all schools and colleges receiving financial aid from the state"; it passed by a vote of 91-3. Several days later, the Georgia Senate passed a bill by a 31-4 vote that prohibited "the playing of football in Georgia and to provide a penalty for the violation of the same." The Senate bill needed only the signature of Georgia governor William Y. Atkinson to become law. But then Rosalind Burns Gammon, the fallen player's mother, wrote the following letter to her local state representative: It would be the greatest favor to the family of Von Gammon if your influence could prevent his death being used for an argument detrimental to the athletic cause and its advancement at the University. His love for his college and his interest in all manly sports, without which he deemed the highest type of manhood impossible, is well known by his classmates and friends, and it would be inexpressibly sad to have the cause he held so dear injured by his sacrifice. Grant me the right to request that my boy's death should not be used to defeat the most cherished object of his life.  1895 Auburn-Georgia Game at Piedmont Park, Atlanta

Instead of punting straight into the leaping bodies of these on-rushing Georgians, he ran a few mincing steps to the right. Raising the ball to his shoulder he tossed it. Luck was with the boy. The ball was caught by a North Carolinian. Now as we today know forward passes it was not much. It traveled a few yards, and laterally as well as forward. It may have appeared to the spectators that it had been knocked from that FB's hands. At any rate that lad who caught it ran 70 yards for a touchdown! Georgia was stunned, not quite realizing what had happened there beneath North Carolina's goal. But Glenn Warner, then coaching Georgia, had not missed a moment of it. And neither had I. I had been standing not more than eight yards from North Carolina's FB. I had seen the first forward pass in football. It was illegal, of course. Already Warner was storming at the referee. But the referee had not seen the North Carolina lad, goaded to desperation, toss the ball. And he refused to recall the ball. A touchdown had been made, and a touchdown it remained. [John W. Heisman, "Fast and Loose," Collier's Weekly, October 30, 1928.]Over the next several years, Heisman campaigned for the legalization of the forward pass, believing its inclusion would open the game up and eliminate many of the sport's serious injuries. Heisman wrote many times to Walter Camp, head of the football rules committee, about legalizing the forward pass, which was finally approved in 1906. The Littlest Pass-Master

Strange But True Football Stories, Zander Hollander (1967)

Even in his padded suit and helmet he didn't look very big, standing among the giants who surrounded him in the Philadelphia Eagles' huddle. But little Davey O'Brien, all 5 feet 7 inches of him, was a brilliant and resourceful field general, who knew that it took more than size to be a winner. Even more, he was a gifted and daring passer. This was O'Brien's second year with the Eagles. It was also his final year and he was playing his farewell game in professional football. Before the game, he had announced that he was retiring to work for the FBI.On this day of December 1, 1940 he wanted to leave something behind for people to talk about after he had gone. He did.

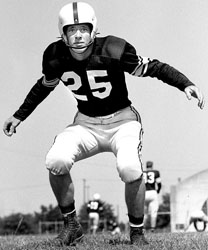

O'Brien was concluding a remarkable football career that had begun at Texas Christian University. There, he broke almost every Southwest Conference passing record and led the Horned Frogs to two national titles in a row. In his senior year he won both the Heisman and Maxwell awards as the outstanding collegiate football player of 1938.  Davey O'Brien, TCU As a result, O'Brien was well known to football fans when he came on the field to direct the hapless Eagles against the might of the Washington Redskins. The Eagles had won only one game all season and were mired in last place. The Redskins were seeking the victory that would assure them of first place in the Eastern Division of the NFL. Many fans regarded the game as the mismatch of the year. A capacity crowd of 25,833 jammed Washington's Griffith Stadium by kickoff time. Despite the uneven match, neither side could score in the first quarter. The Eagle line was outweighed and outrushed by the Redskin forwards, who threw back the Eagle runners for more yards than they could gain. So, early in the second period, little Davey took to the air. He began to fill the air with more passes than any pro-football crowd had ever seen before. Not even the dynamic Redskins seemed capable of stopping him. The Redskins did manage to break through on the scoreboard, however, on a 27y reverse ... The Redskins missed the extra point and led, 6-0.

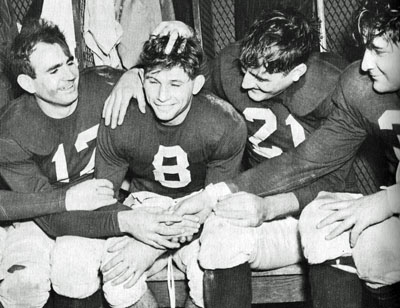

But O'Brien did not relax his passing attack. To elude the onrushing tacklers, he faded back as far as 15 and 20y behind the line of scrimmage, picked out his receivers and completed his passes. And when he couldn't find anyone free, he ran with the ball. On two successive plays he gained 34 yards on runs, nearly twice as many as the rest of the team would make on the ground all day. He mounted a drive that carried the Eagles 64y in five plays, and seemed headed for the tying touchdown when the halftime gun went off. In all, Davey had completed 11 passes for 112 yards in the first half.That was only a warmup for what was to come. He continued his assault in the second half. Despite the growing pressure being put on him by the Redskin linemen, Davey managed to connect on passes with ridiculous ease. He passed wide to the side and he passed deep; he threw from behind his own goal line and he threw on the dead run, riddling the Redskins defense with his slingshot passes. He was the little David against the Goliaths of the league, a sprite standing up against the six-foot, 230-pounders who seemed to be trying to separate his head from his shoulders Often enough they got to him and smashed the little man to the ground. But each time he would pick himself off the turf and go back to work. Every now and then a Redskin lineman would help him to his feet, apologizing for having knocked him down. Meanwhile, the Redskins, masterminded by Sammy Baugh, who had preceded O'Brien at TCU, scored on Dick Todd's plunge from the four-yard line. With Bob Masterson's kick the Redskins now led 13-0. Still, O'Brien would not quit. Playing all the way on offense and defense, he stimulated another Eagle drive. He engineered two drives in the third period, one of them for 68y in 12 plays, and another for 66y in five plays. But the Eagles still couldn't get the ball across the Redskin goal line. The Eagles' predicament looked even gloomier in the fourth quarter when Baugh, an excellent punter, quick-kicked, and the ball traveled 85 yards before it was downed on the three-yard lien. But O'Brien charged up the Eagles once more. He began pumping passes immediately. His primary target was left end Don Looney, who was to catch a record 14 passes for 180 yards during the day. In 15 plays, he drove the Eagles all the way, finally scoring with a 13y pass to FB Frank Emmons. The try for the extra point was blocked, and the Eagles trailed, 13-6. Time was running out now, but not O'Brien's courage. As soon as the Eagles got the ball again, O'Brien began one last drive that carried them down to the Redskins' 33. He was still flinging passes into the end zone, trying for the trying score while being rushed by six or seven men at once. But with 17 seconds showing on the clock, and O'Brien's endurance waning, Coach Bert Bell took him out of the game. He had played for 59 minutes and 43 seconds of a grueling football game, and he had thrown an unprecedented total of 60 passes. And not one of them was intercepted! Overall, Davey completed 33 of his passes for 316y. As Davey came to the sidelines, a dejected little figure in a mud-caked jersey with the numeral 8 on it, everyone in the ballpark stood up and cheered for his remarkable demonstration of courage and skill. Even the Redskin players openly applauded him as he walked off the football field for the last time. The Eagles were beaten, 13-6, but not vanquished. Davey's performance that day remains an indelible memory, even though most of his marks have since been erased. But the one that still stands is his 60 passes. [The record was finally broken by Joe Namath, who threw 62 for the Jets against the Baltimore Colts in 1970, three years after this story was written.]  O'Brien with his mates after his last NFL game War and Pieces

The Trojans: A Story of Southern California Football, Ken Rappoport (1974)

By the late 1930s, UCLA had begun to challenge USC's football supremacy in the City of Angels. In the opening game of the 1941 season between UCLA and Washington, six members of a Southern Cal fraternity furtively joined the Bruin rooters. After the game they helped UCLA students load their Victory Bell into a truck for the trip back to the Westwood campus.

One of the Southern Cal students stole the truck keys. And while the UCLA students went for another set, the Trojans drove off with the truck and the bell. The theft of the 295-pound locomotive clanger and the subsequent search made the bell a fighting symbol between Southern Cal and UCLA. For more than a year it was hidden, first in the Hollywood Hills and then in a Santa Ana haystack. The police were called in on the search, but were just as unlucky as UCLA students in finding the object. After a series of cross-town raids, the student body presidents of both schools met to negotiate an end to the search. Southern Cal agreed to return the bell - on the condition that it would be a permanent game trophy. The next year Southern Cal lost it back to UCLA. Beaten for the first time by the Bruins, 14-7, the Trojans came to a stark realization that the city of Los Angeles no longer belonged to them. Forever the king of southern California, the Trojans now reigned with another. The Victory Bell caper symbolized this new co-existence. And compared to other tom-foolery between UCLA and USC students, it was relatively tame.

Starting in the 1940s, Southern Cal-UCLA games transcended the football field and split the city of Los Angeles in half. UCLA was a football power on the rise, and Southern Cal was coming back down to earth after the Howard Jones years.

The fierceness of this rivalry was mirrored in campus pranks. The week after the football teams played to a 7-7 tie in 1941, a vicious scrimmage took place between students of UCLA and Southern Cal. When four Southern Cal students took the locomotive bell over to the UCLA campus, they were pulled from their truck, dragged before the student body, and had their heads shaven. Later a large procession of UCLA students, who had attended a victory rally on the Westwood campus, drove their honking cars to a downtown Los Angeles intersection and blocked traffic for hours with varied stunts. Accompanying them was the school band. Later in the day Southern Cal students got even for the UCLA indignities. When 20 carloads of UCLA students invaded the Trojan campus with the taunt, "Rose Bowl, here we come! Ex-Trojans, we're sorry for you!" they paid for it. Irate Southern Cal students dragged their UCLA counterparts through a series of humiliations. They shaved their heads and painted "SC" on their skulls. They forced them to clean blue paint off the Tommy Trojan statue. (UCLA students had previously painted the Trojan symbol with the Bruins' color.) And they dumped them into a fish pond with the chant, "Fish Bowl, here we come!"  Campus frenzy became icily scientific when it pertained to Southern Cal and UCLA. Southern Cal "spies" infiltrated UCLA one season and schemed to disrupt the Bruins' card stunts at football games. A red-and-gold "SC" appeared in one corner of each card stunt picture, much to the puzzlement of UCLA students.  USC Card Stunt Sabotage Dan Berger, a sportswriter for the Associated Press in Los Angeles, remembers another devious Southern Cal plot. "The shop that printed the Daily Bruin at UCLA was invaded, stories were stolen and rewritten, pictures and captions were changed, and a bogus edition was printed by Southern Cal students. Then the Trojan pranksters kidnapped the truck driver who delivered the UCLA papers and replaced the genuine with the phonies. When UCLA students opened their daily paper the next day, they read the team's star QB saying, 'I'd feel much better about our chances against those terrific Trojans if we had a couple of players who understood the game.' The coach added, 'I can't see any hope for our team.'" "Night Train"

"Yesterday's Heroes," Jerry Green, GameDay Saints vs. Falcons January 2, 1983

The bus cost a dime back then, and as it rumbled through Hollywood the soldier wondered how he would spend the rest of the day. He shuffled around and looked out the window.

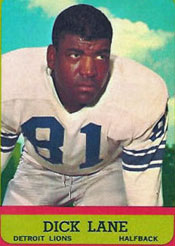

There on the corner of Beverly Boulevard and Fairfax Avenue the soldier saw the sign on the top of the squat office building. It said: "Rams." The soldier jumped up, yanked the cord, and got off the bus. He was named Richard Lane and came from Texas. He had played some football at a place called Scottsbluff Junior College in Nebraska. This was during the Korean War, and Richard Lane had been drafted and went to Fort Ord, California. He played football for the Army and kept the documents to prove it.

Now he was off the bus and walking into the squat building, asking to visit the coach. The year was 1952, and Richard Lane to this day relishes repeating this story.

"I got off the bus," Lane says, "because I had a letter from Joe Stydahar, who was coach of the Rams then, and he had said to stop by. Buck Shaw, who was coaching the San Francisco 49ers, had sent me a letter, too. But he said, 'Come by when you're out of the service,' and Stydahar had just said, "Stop by' at any time. So I got off the bus." Lane managed to talk himself past the office receptionist and soon found himself in Stydahar's office. Of such raw stuff are sporting legends started and nurtured. Lane made the Rams that season. He intercepted 14 passes (still an NFL record) at a position that years later would be named cornerback in pro football's nomenclature. He played 14 years in the NFL for the Rams, the Chicago Cardinals, and finally the Detroit Lions. Nine years after his retirement, he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. The vote was unanimous. Richard Lane was the square name for the gambling pass defender better (and more romantically) known as Night Train Lane. The nickname is another episode of the legend. "My rookie year with the Rams, that was the year the record 'Night Train' came out," Lane says. "I listened to it a lot. I was an offensive end at the start and Tom Fears was playing with the Rams then, so I used to go to his room at training camp for advice. "Every time I went to Fears's room, Ben Sheats - he was another rookie - said: 'Here comes Night Train.' Then I became a defensive back and we played our first exhibition game, and a headline came out after that game: "'Night Train Lane Derails Charley (Choo Choo) Justice.' I tackled him, and he broke his shoulder. I thought the name looked pretty good. It's been a good name." Derailment was Night Train Lane's game. The visions are imperishable. ... The quarterback throws the football. The receiver is open. The defender, lagging inside, is beaten. Cleanly. Now there is a blur, a quick, precise, calculated movement from the defense. The airborne football fails to reach its destination. Night Train Lane, so swiftly, is between the quarterback and the receiver. It is his football. A winning roll, shoot it all on the seven. Night Train played the corner as a high-stakes gambler. That was his style, but he wouldn't admit it. "You can't play a guessing game, they'd kill you if you did," he says. Today Night Train Lane is 54, he plays a lot of golf at NFL Alumni events, shoots in the low 80s. He is working on a dual biographical book about himself and his late wife, singer Dinah Washington. And he has a desk job. He has been director of the Detroit Police Athletic League for seven years.

"Any of y'all who want to go back home just see me." The Junction Boys: How Ten Days in Hell with Bear Bryant Forged a Championship Team,

Jim Dent (1999)

August 31, 1954

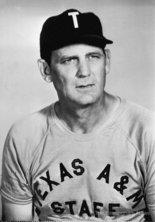

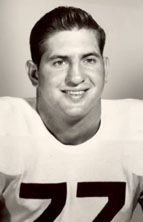

Bear Bryant wore the scowl of a man who'd eaten spark plugs for breakfast and washed them down with a quart of Tabasco. "We're 10 percent silk and 90 percent sow's ear," he confessed to (assistant coach) Pat James. "Half the team is smaller than a monkey's cojones. The other half is slower than smoke off shit." It was a hot and muggy morning when the players returned to College Station ... Parked in front of Walton Hall, the football dormitory, were two long diesels with KERRVILLE BUS LINES painted across the sides. ... Preseason practice had been held for decades a half-mile away. So why, the boys were asking, would they need two buses to travel just down the street? After completing their summer jobs, many of the players had hitchhiked back to campus. Others had hooked rides with teammates. Few could afford cars or pickups. Some took the train, and others arrived by bus. They toted beat-up suitcases and stringed-up boxes, and their football shoes were tied together by the laces and draped over one shoulder. Most were deeply tanned from working in the oil fields and on the ranches during the hottest summer any Texan could remember. They were eager yet apprehensive. Most of the players secretly wished that Ray George was still coaching the team, even though his easygoing nature promoted laziness. At least he didn't seem hell-bent on fracturing bones and postholing them into the sun-baked ground. They couldn't remember a player ever being run off by Ray George. At ten that morning, Bryant gathered the players at the front entrance to Walton Hall. Most were still carrying their gear. Wearing khaki pants and a gray T-shirt, he loomed even larger and more intimidating than they had remembered. "I suppose you boys are wonderin' what the buses are for," he asked in a low rumble. "Well, we're going on a little trip. I want you to take your stuff up to your rooms. There's no need to unpack your bags. Just grab a toothbrush, a blanket, and a pillow. After that, go to the chow hall and grab a baloney sandwich. We'll meet back here in about 15 minutes. So be ready to go." As the players dispersed. Bryant spoke up again. "One more thing. Don't call anybody and tell 'em we're leaving campus. No phone calls, understand? When we get to where we're going, you can write a letter to your mamas and your papas." ...    L-R: Bear Bryant, Ray George, Willie Zapalac Now his dorm room seemed to be a mile away - far up the steps on the I Ramp of Walton Hall. Players with the best chance of making the team were on A, B, and C Ramps. His roommates were the type of players Bryant hoped to run off long before the first game of the 1954 season. It was clear to many of the boys that Bryant was planning a grand going-away party bfore the Aggie alums or the university's administrators could get wind of it. Like most of the other players Billy rolled up his toothbrush and comb in a blanket, grabbed the pillow from his bunk bed, and then sprinted to the chow hall across the street, hoping to learn that his name hadn't already been scratched from the roster. Bad news awaited several players before the buses took off. It was scrawled there on the chow hall chalkboard. Bryant had spent the summer evaluating talent, and many players would be changing positions. Because the Aggies needed bigger boys in the line, Bill Schroeder was moving from end to tackle. Several of the slow running backs were shuttling to guard and tackle. It was easy to spot the players who'd learned they'd be swapping backfield glory for grunt work. Their eyes were glued to the floor. All but Schroeder. "I'll do whatever it takes to help the team," he said to anyone within earshot. ...    L-R: Billy Granberry, Bill Schroeder, Don "Weasel" Watson Bryant gazed through the morning haze and had a vision. He could see overfed Aggie alulms - a passel of weirdos, he thought - wearing Bermuda shorts, sandals, and black socks. Soon, they would be gathering on the sidelines of the practice field, waiting for the team to start fall parctice. They would stand there maybe an hour in the searing heat, bitching and wondering where the hell the football team was. Then, around noon, the crusty old groundskeeper would limp across the field. "Bear took the boys away on two buses," he would say. "I don't know where they're going. He didn't say when they'll be back." Bryant had started cooking up this secret trip at the end of spring training when he got fed up with the meddling jock sniffers. Willie Zapalac told him about a place on the western edge of the Hill Country ... where Texas A&M conducted summer school for incoming freshmen along with courses in hydraulics, surveying, and agriculture research for upper-class Aggies. The Texas A&M Adjunct, as it was called, boasted 411 acres and had 20 screened Quonset huts, a classroom building, a bathhouse, a mess hall, and a physical pllant building. The camp was about two miles from downtown Junction, a flyspeck on the Texas map with a population of about 2,000. ... In July, Bryant had dispatched Zapalac and Phil Cutchin on a fact-finding mission. Cutchin had his reservations about taking the team so far to such a crude place, especially one with so much cacti. But Zapalac was intrigued with the place. "Coach, it kinda looks like an old army base, even though it's pretty new," he said. "They didn't waste much money slapping it together, but there's a helluva lot of land. ..." What sold Bryant was the remote location. It would take weeks for the Aggie leeches to locate Junction, and the staff would have no trouble shooing away local folks who wanted to watch practice. No press would be poking around. Mamas and papas might worry about their boys but wouldn't know where to find them. Bryant could teach the boys to play football his way - or they could hit the highway. As the buses rolled into the vast countryside ..., Zapalac stood in the middle of the aisle and held several strips of bus tickets above his head. "You boys listen up. Any of y'all who want to go back home just see me. I got plenty of bus tickets. Be happy to give you one." The boys were confused. But only Weasel Watson had the guts to speak up. "Coach," he said, "why you figure us boys would be interested in going home so soon? And where in the hell are we going anyway?" Zapalac looked at Bryant, who nodded. "We're goin' to a place called Junction." To be continued ... Hell - Part 2 The Junction Boys: How Ten Days in Hell with Bear Bryant Forged a Championship Team,

Jim Dent (1999)

September 1, 1954

It was the kind of deep silence you can feel on a dew-covered morning in the Virginia backwoods, or on a snowy mountaintop, or in the Texas Hill Country in the middle of the night when even the crickets have dozed off. That stillness was shattered at 4:00 A.M. when Troy Summerlin sprinted through the first Quonset hut shining a flashlight and blowing a coach's whistle. Behind him rambled Billy Pickard, banging together two cook pots. The noise could have woken a dead man. ... More than an hour later, with players now fitted with helmets and uniforms, they began lining up for calisthenics on the rugged field that had been partially cleaned but was still littered with rocks, cacti, and sandspurs. Not once could the boys remember practicing football in the dark, or having to dodge cactus, for that matter. The moment that Bryant's barracks door shot open, though, the sun popped over the tall, craggy hill overhead. ... What Bryant saw in the first light of morning were ten rows of players wearing five different colored jerseys. Maroon was for the first team, white for the second, blue for third, orange for fourth, and yellow for the fifth-teamers and anyone else without a designation. From day one, Bryant wanted his players to understand exactly where they stood in the team's pecking order. The different colors created tension among the troops, and Bryant liked that. They were a ragtag bunch of skinny boys with drooping pants and scarred-up helmets. Not once in his coaching or playing career had Bryant seen more pathetic equipment. The inner suspension of several helmets had either frayed or broken through. Heads would be cracking against the hard plastic. Many of the Plexiglas face masks didn't fit properly and wobbled when the boys ran down the field. In spite of the stifling heat, players wore long-sleeve jerseys. Somebody had forgotten to pack the short-sleeve ones. ...     L-R: Bear Bryant, Frank Leahy, Richard Vick, Elwood Kettler

The sun had climbed far into the pale blue sky and the gravel pit known as the practice field was dotted with orange juice stains when the 80y wind sprints, also known as gassers, finally ended. More than 20 times the boys had chugged to the other end of the field, taken a short break, and then wobbled back, stirring up clouds of thick dust. Just as Bryant predicted, the boys were vomiting everything in their stomachs - the orange juice, vitamins, and salt tablets. Bryant seemed happy to see the boys bent over and puking so early in the morning.

A big part of the master plan was to shock their systems and separate the quitters from the keepers.Meanwhile, the Man would also demonstrate how he organized and executed precision practices. When he sounded a whistle, the boys would break up into eight groups to participate in different drills. The assistant coaches ... carried clipboards and were in charge of leading the drills while Bryant moved from station to station, riding herd. Only a handful of coaches around the country ran such regimented practices. Bryant patterned part of his plan after Frank Leahy, the legendary coach who'd just retired from Notre Dame. At the sound of Bryant's whistle, players moved like clockwork to different drills. Bryant had already gained a reputation as a brutal taskmaster. But at least he was systematically brutal. ... Standing with his hands on his hips, monitoring a drill run by Zapalac, Bryant began to holler, "No, Willie! Get the sonofabitch into a stance like this and bring the forearm up like this." Shoving Zapalac aside, Bryant hiked his pants and dropped into a three-point stance. Charging forward, he thrust a forearm into the sternum of unwitting center Richard Vick, lifting him a foot off the ground. The breath could be heard whooshing from Vick's lungs as he landed with a thud on his back. Bryant smiled. He was just getting warmed up. Minutes later, Bryant watched a two-on-one blocking drill that was getting the best of Henry Clark, a tall and broad-shouldered tackle ... Clark's objective was to penetrate the wall of blockers and tackle the running back. Henry was failing miserably. As he gasped for air, Bryant could see his legs wobbling from near-exhaustion. With each snap, Henry was engaged by a fresh set of blockers, and each time he was knocked backward and pancaked to the ground by both men. Henry's body was raising a dust cloud almost waist-high every time he landed flat on his back. Bryant grabbed the big tackle by the shoulder pads and shouted, "What is your name, son?" Breathing heavily, the boy said, "H-Henry Clark." Bryant released the boy and blew his whistle. "I want all of you sonsabitches on this practice field to stop and listen up, because this boy tells me his name is H-Henry Clark. Now I want you to see how a fart blossom named H-Henry Clark handles himself." The players could see Henry's legs trembling as he dropped into his stance. A small running back named Charles Hall spoke up. "How can we all stand here while this man abuses our teammate like this?" "Shut up, fool," Elwood Kettler said, "or you'll be next." Again Clark crumpled beneath the weight of two blockers. He was dragging himself to his feet when Bryant grabbed the boy's jersey and spun him around. Seizing the inner part of his shoulder pads with both hands, Bryant pulled Henry's face close to his. "You ain't worth tits on a boar hog. And you call yourself a Texas Aggie football player." The man with the leather exterior had rehearsed in his mind this little theater that would teach all the boys a lesson in toughness. He ripped Henry's helmet from his head and grabbed the back of the boy's head with two meaty hands. "Now I'm gonna show you how to do this goddamn drill." Bryant then butted Henry in the hose with his forehead. He yanked his head forward again and again, bashing his skull into Henry's nose, lips, and eyes. Blood poured down Henry's neck and began to soak his white jersey. Even from 40y away, players could hear the sickening thud as Bryant's forehead slammed into the boy's face. Finally, Henry fell like a sack of potatoes onto the hard ground. Stumbling forward, blood smeared across his forehead, Bryant breathed heavily as he turned toward the team. "Trainers! Get your butts over here and fix this boy's broken nose." The coach had three cuts on his forehead. Henry's shattered nose had been shoved an inch to the right. Blood flowed from his gashed lips. Soon his eyes would be swollen shut. First, though, Smokey Harper had to wake him up. Snapping an ammonia capsule, Smokey crammed it into one of Henry's blood-caked nostrils. "Stand back," Smokey said, acting as if he'd lit a firecracker. "He'll be shakin' and rattlin' any minute." But Henry couldn't inhale the harsh amonia for the coagulated blood. So Billy Pickard pulled a large swath of cotton from his bag and began clearing the breathing passage. Billy snapped another capsule about an inch from Henry's nose, and he jerked awake. Standing a few feet away, Bryant said, "Billy, fix his nose and tape him up. Give him a little break. But I want him back on the field before this practice is over." [Postscript: Henry Clark made the 1954 Aggie team as an offensive lineman.] Death of the PCC

College Football: History Spectacle Controversy, by John Sayle Watterson (2000)

The NCAA between 1954 and 1957 gradually tightened its grip on college football. To be sure, the NCAA strongly reflected the policies and the agenda of the Big Ten working in tandem with the increasingly scandal-stricken Pacific Coast Conference. ... In 1953 the NCAA put Arizona State on two-year probation for the activities of its booster group ... In the same year, Notre Dame was censured for providing tryouts for football players in violation of NCAA bylaws; the association also censured Michigan State, where the Spartan Foundation boosters had made $55,000 in illegal payments to players between 1949 and 1952, enabling it to build a national championship team. ...

In the wake of bitter and tawdry scandals in the Pacific Coast Conference, the NCAA imposed tough sanctions on four PCC schools, Washington, UCLA, California, and Southern California. UCLA's penalties proved to be particularly harsh; it received a three-year probation, during its probationary status it could not appear on television ... the NCAA's Infraction Committee prohibited the institution from participating in any NCAA-sponsored event. ... Southern California could not appear on television or participate in the Rose Bowl. ...In 1952, the NCAA had taken up out-of-season practice, one of the measures that the ACE proposals had sought to eliminate and the Ivy League ... succeeded in doing. At the annual NCAA convention Victor O. Schmidt, PCC Commissioner, ... moved to outlaw out-of-season practice except for postseason games to be held no later than January 2 (to allow for the Rose Bowl) and continuing until September 1 ... After strong opposition by Fritz Crisler of Michigan ... the convention decisively defeated Schmidt's motion, though it then proposed and passed a measure allowing 20 days of football practice in the time span of 30 days.    L-R: Ronnie Knox, Johnny Cherberg, Pappy Waldorf To put it bluntly, rivalries between flagship institutions in the PCC resembled grudge matches more than traditional rivalries. ... UCLA still felt the stigma of its origins as a storefront satellite campus of California ... One PCC school where cheating first came to light was Oregon, whose football coach had engaged in illegal recruiting practices such as offering $100 per month as well as a clothing allowance to a promising recruit. When this scandal erupted in 1951, Commissioner Schmidt threatened the institution with expulsion and insisted that the school fire its football coach. In turn, Oregon suggested that other schools, such as UCLA, were just as guilty of PCC code violations. ... The first big-time slush fund scandal erupted at California in 1954, after Ronnie Knox, a highly sought-after HB from the Los Angeles area, revealed the existence of recruiting violations upon quitting California to transfer to UCLA. ... As a result, Schmidt levied sanctions on Cal which would keep it from going to the Rose Bowl. ... Knox transferred to UCLA, where he received $75 for a nonexistent college job and $25 a week in the film-cutting department of a movie studio. ... In an article written for Collier's in 1956, ... Knox wrote that UCLA ... provided its players with "enough money for room and board, even though the rules of the conference forbade it." ... In the fall of 1955, the scandal virus struck at Washington, where the faculty athletic committee had fired coach Johnny Cherberg after the players had complained of his ineptness in handling the team. Cherberg immediately revealed the existence of a booster fund ... which recruited players by making illegal promises of cash payments and then paying the players. ... The PCC put the Huskies on probation for two years, banning the team from appearing in the Rose Bowl. In March 1956 charges of slush funds cropped up at UCLA when a former player who had moved to California revealed the existence of ... booster operations that supplied players with a $40 monthly stipend - and had been helping players since the 1930s. ... UCLA chancellor Raymond Allen refused to allow Commissioner Schmidt to interview the athletes for ten weeks, while Allen claimed to be making his own investigation. As a result, the commissioner assessed the chancellor with a fine of $95,000. The PCC also docked the whole football team a year of eligibility, a factor that led Ronnie Knox to forgo his senior year and join the pros [in Canada]. ... Then the spinning wheel stopped at USC's doorstep in July 1956. Miller Leavy, a UCLA alumnus who served as deputy district attorney, sent Schmidt documents on the activities of the Southern California Educational Foundation, which had given more than $70,000 to athletes on the USC team ... The conference banned the Trojans from the Rose Bowl and exacted a fine of $10,000 for USC's failure to cooperate with Schmidt's investigation. As at UCLA, 42 members of the team would have to sit out a year of competition ... Politicians and boosters in the L.A. area poured out vitriol on the conference authorities, the northern California schools, and the institutions of the Northwest which had, they believed, been responsible for the severe sanctions. ... Soon afterward, the ubiquitous Miller Leavy turned his heavy artillery on the north, sending evidence to Schmidt that booster clubs at California gave money to football players for non-existent jobs. In response, Chancellor Clark Kerr conducted his own investigation and publicly reprimanded Coach Lynn "Pappy" Waldorf. The PCC levied a fine of $25,000 against Cal, a penalty well noted by southern California schools as far less than those imposed on the Los Angeles schools. Given the acrimony ..., the California schools, except for Stanford, embarked on a course designed to break up the conference. In 1957 the PCC tried to overcome what the New York Times called "a ground swell of disapproval" leading to cries for secession. The faculty representatives changed the financial rules so that players could receive aid if they could not make ends meet. While they refused to eliminate the probationary status for UCLA, USC, and Cal, the faculty reps did scale back the full year's disqualification for the UCLA athletes, changing it to a two- and three-year probation. This meant that the seniors could play but could not qualify for the conference championship or a trip to the Rose Bowl, the only postseason competition that the conference allowed. Putting aside its resentments, Cal joined the two indignant Los Angeles schools in plotting their withdrawal from the PCC. ... In late 1957, when the PCC held their annual meeting, the schools forced Schmidt to resign, and then a week later California, UCLA, and USC voted to leave the conference. As a major football power, Washington would no longer have games with the powerful California teams except for Stanford; it might also have trouble recruiting in pigskin-fertile California. Therefore, Washington submitted its resignation in June 1958. The five schools that remained - Stanford, Oregon, Oregon State, Washington State, and Idaho - dissolved the "strife-weary" loop in August 1958. ... When the West Coast teams reorganized in 1960, they created a new conference, the Athletic Association of Western Universities (AAWU), or Pac-8 and later the PAC-10, including all of the same teams except Idaho. "Jerry Stovall Joins LSU Legends with Jersey Retirement,"

Cody Worsham, LSU-Georgia football program (2018) He didn't realize why they were laughing. Jerry Stovall was just one freshman among dozens, standing in front of the Cage, as trainers sized up each new player for his equipment.

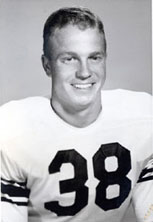

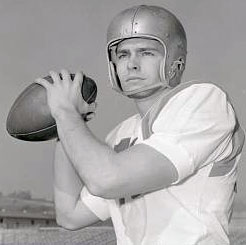

What size pants do you need? What size shoes do you wear? What size helmet are you? And the last question from Jim Smith, the football equipment manager in 1959: What jersey number would you like? That was easy. Stovall had worn the number in high school, and so, he would wear it in college. "Well," Stovall told Smith, "I'd like number 20." "Dumb me," Stovall laughs today. "I was a freshman, I wasn't old enough to know better." That number, unfortunately, was taken. Billy Cannon would wear it while winning the Heisman that year, just one year removed from winning the national championship. LSU would retire the number immediately after the '59 season. Stovall, the last man signed in his recruiting class, would have to pick another number. He asked Smith which number closest to 20 was available. "18 and 21," Smith replied. "I said, '21 will do,'" Stovall recalls. "So I got 21 because Billy Cannon had number 20, and he had priority over me." Now, their jerseys are retired together. Stovall's No. 21 joins Cannon's 20 and Tommy Casanova's 37 as the ony ones retired in LSU football history. "Good gracious," Stovall asks, "how lucky can a man be?" The first name Jerry Stovall can't remember paved his improbable path to LSU. A versatile star in all three phases at West Monroe High School, Stovall had offers from Northeast Louisiana University and Louisiana Tech. He first caught the eye of LSU through Red Swanson, a former Tiger assistant coach turned Board of Supervisors member. Swanson was working at the Louisiana Training Institute when West Monroe and LTI squared off, and Stovall's do-everything approach jumped out to him. "Just keep working hard," Swanson told Stovall, "and good things are probably going to help to you." Soon, the two were taking trips to Baton Rouge for LSU home games in Swanson's black Buick Roadmaster, which Stovall recalls "sounded like a gorilla" when it started up. On the way, they'd talk football, bonding over the sport. The idea of staying close to home at either NLU or Tech had appealed to Stovall, but then he saw Tiger Stadium in person. "It was like going to the circus," Stovall recalls. "There were 60,000 people going into the stadium. There were ex-athletes all around, everybody in the world is having a good time. I thought, Man, if this is like this all the time, it'd be a nice place to play." Meanwhile, LSU was warming to the idea of Stovall. Assistant coach Abner Wimberly headed up his recruitment, driving to West Monroe to watch Stovall's high school film. "I was black and white, grainy film," Stovall says. "I know he didn't see anything flashy. You've never heard anybody talk about Jerry Stovall's outstanding speed, great size, great strength. It's real simple. I didn't have those things in my tool chest. The only thing I think I had working for me was what my daddy taught me: you've got to work as hard as you can, for as long as you can, so you can become the best you can, so you can become the best you can. The only thing I had going for me was that I was going to work hard."    L-R: Jerry Stovall, Abner Wimberly, Marty Broussard The second name Jerry Stovall can't remember paved his improbably path to the field at LSU. Tough and hard-working, Stovall was behind the curve athletically when he arrived in Baton Rouge. Swanson had cautioned the LSU beat reporters at the time: "He might not be as far advanced as some of the boys the Tigers have signed, but he is all around and does everything well. Give him a year to get adjusted and he's going to surprise a lot of people." Stovall had no idea if he was ever going to see the field. "Everybody I saw was always bigger, faster, stronger than me," he says. "Somebody was going to have to get hurt, somebody was going to have to quit, or I was going to have to do a really good job of working hard to prove to them I want to play." Hitting the weight room sure helped. Stovall had never lifted weights in high school, but LSU was ahead of its time in strength and conditioning. Dr. Marty Broussard had installed a weight lifting program program that Stovall took to quickly. "I never lifted weights in high school," Stovall says. "Marty Broussard demanded work. He demanded excellence. When you give it to him, he responds." Stovall's breakthrough, oddly enough, came on the wrestling mat. The Tigers trained in a padded room twice a week during the offseason as part of their conditioning, and Stovall's first grapple came against future first-round NFL draft pick Wendell Harris. The rules of the match, as explained by then-defensive coordinator Charles McClendon, were simple: no biting, no head-butting, no eye-gouging, and no choking. "They blow the whistle, and three minutes later, I've been humiliated," Stovall recalls. Wendell Harris put me upside down, against the wall. He butted me. He put his hands places he wasn't supposed to. He did a lot of things he wasn't supposed to. The whistle blew. Thank God I'm alive. I rolled over, sheepishly getting up, and Coach McClendon screamed at me: 'We don't walk or roll around at LSU!'" That night, Stovall made a deal with God: If you let me live until next Thursday, I am going to kill somebody. The following Thursday, it was back to the wrestling room. This time, the opponent and the outcome were different. "I can tell you the guy who whipped me so bad in Wendell Harris, but I cannot tell you - this is the second name I wish I had - I cannot tell you who I wrestled the second time," Stovall says. "But I did to him everything Wendell Harris had done to me. Coach Mac blew the whistle. I popped up like I knew what I was doing. I was strutting back to the place where a week before I'd been rolling around." That's when he caught Broussard's eye. "When I went back, Doc Broussard - do you know what that guy did to me?" Stovall asks. "He winked at me. Do you know how much strength and devotion and loyalty is in a wink? Whatever Doc Broussard wanted me to do from that point forward was done, as best as I knew how to do it." From there, the wins flowed, and the accolades followed. After a 5-4-1 record his sophomore season - featuring three losses by three points or less and following the graduation of Cannon and his title-winning classmates - Stovall's junior and senior squads went a combined 19-2-1. He earned first-team All-SEC honors each year, winning the SEC title in 1961 and the league's Most Valuable Player honors in 1962, when he also finished runner-up in the Heisman voting and was named a unanimous All-American. ... What turned a self-described "average athlete" into an All-American, first round NFL Draft pick, and two-time all pro? Unwavering belief in a simple motto passed down from his father: "Work as hard as you can, for as long as you can, so you can become the best you can possibly be." ... |