|

The Richest Rivalry

Fourth and Long: The Fight for the Soul of College Football, John U. Bacon (2013)

Michigan and Notre Dame started going at it when they first met in 1887 - by accident. The Michigan football team was traveling to Evanston to play Northwestern when they learned the "Purple" were backing out. So they got off the train at South Bend instead and literally taught those Notre Dame boys how to play football.

After the Wolverines won that first contest, 8-0, Notre Dame treated their guests to a hearty banquet. The mood was so friendly that Notre Dame president Thomas Walsh felt compelled to give a toast, assuring the Michigan players that a "cordial reception would always await them at Notre Dame." Promises, promises. No self-respecting Michigan or Notre Dame fan cannot repeat the history that follows. This synopsis is for the rest of you. In 1895, representatives from seven schools - Michigan, Purdue, Illinois, Chicago, Northwestern, Wisconsin, and Minnesota - met at the Palmer House in Chicago to create what we now call the Big Ten. Because Notre Dame was still an embryonic team at a small, struggling school, no one considered inviting them to join. Notre Dame's relationship with the Big Ten became more complicated after coach Fielding Yost arrived at Michigan, and a player named Knute Rockne enrolled at Notre Dame. In 1910, Yost accused Notre Dame of using ineligible players and cut the series off. On the various all-American teams that big-name coaches selected in 1913, only one coach left Rockne off his list - and that man was Fielding Yost.   L-R: Fielding Yost, Knute Rockne Things got worse after Rockne became Notre Dame's coach in 1918, and then blew up beyond repair in 1923 - at a track meet. Yes, a track meet. Rockne got into a shouting match with Yost over the distance between the hurdles Michigan had set up. Yost vowed then and there that Notre Dame - which had desperately been trying to get into the Big Ten - would never be admitted.

The animosity between these two giants ran at a fever pitch the rest of their lives. When a Spalding salesman tried to get Rockne to order new equipment, Rockne kept repeating that he was already overstocked with everything he needed. Finally, just before turning to go, the clever salesman sighed and said that was a shame, because Yost liked Spalding's new footballs so much he'd ordered three dozen. "He did?" Rockne snapped. "Then I'll take three dozen and a half." The teams ended the embargo during World War II, when they split two games, before cutting off the rivalry again. Another tradition that goes back almost as far as the rivalry is the mistrust between the teams' leaders. Like all great traditions, this one has outlived its originators. Michigan's Fritz Crisler didn't trust Notre Dame's Frank Leahy any more than Rockne trusted Yost. Pressed to explain why, Crisler cited this example: Whenever someone asked Leahy if he wanted a cigarette, he'd say yes, then just play with the thing without ever lighting it. "Why," Crisler asked, "doesn't he just say he doesn't smoke?" ...   L-R: Fritz Crisler, Frank Leahy At a banquet in the late sixties, Notre Dame athletic director Moose Krause leaned over to his Michigan counterpart, Don Canham, and said, "Don, Michigan and Notre Dame should be playing football." They were the two winningest teams in the game's history, they both had earned reputations for doing it the right way, and they were only three hours apart. Canham couldn't argue with the logic of it. After a few years of touchy negotiations, they relaunched the rivalry in 1978, and it was an immediate hit. The games were so good Sports Illustrated put the rivalry on the cover four times in a decade, plus four features - each time eclipsing the NFL's opening weekend, and tennis's U.S. Open.

The Littlest Pass-Master Strange But True Football Stories, Zander Hollander (1967)

Even in his padded suit and helmet he didn't look very big, standing among the giants who surrounded him in the Philadelphia Eagles' huddle. But little Davey O'Brien, all 5 feet 7 inches of him, was a brilliant and resourceful field general, who knew that it took more than size to be a winner. Even more, he was a gifted and daring passer. On this day of December 1, 1940 he was playing his farewell game in professional football, and he wanted to leave something behind for people to talk about after he had gone. He did. This was O'Brien's second year with the Eagles. It was also his final year and he was playing his farewell game in professional football. Before the game, he had announced that he was retiring to work for the FBI. O'Brien was concluding a remarkable football career that had begun at Texas Christian University. There, he broke almost every Southwest Conference passing record and led the Horned Frogs to two national titles in a row. In his senior year he won both the Heisman and Maxwell awards as the outstanding collegiate football player of 1938.

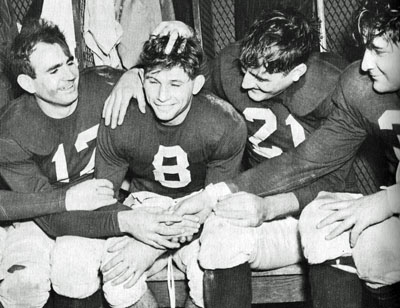

Davey O'Brien, TCU As a result, O'Brien was well known to football fans when he came on the field to direct the hapless Eagles against the might of the Washington Redskins. The Eagles had won only one game all season and were mired in last place. The Redskins were seeking the victory that would assure them of first place in the Eastern Division of the NFL. Many fans regarded the game as the mismatch of the year. A capacity crowd of 25,833 jammed Washington's Griffith Stadium by kickoff time. Despite the uneven match, neither side could score in the first quarter. The Eagle line was outweighed and outrushed by the Redskin forwards, who threw back the Eagle runners for more yards than they could gain. So, early in the second period, little Davey took to the air. He began to fill the air with more passes than any pro-football crowd had ever seen before. Not even the dynamic Redskins seemed capable of stopping him. The Redskins did manage to break through on the scoreboard, however, on a 27y reverse ... The Redskins missed the extra point and led, 6-0.

But O'Brien did not relax his passing attack. To elude the onrushing tacklers, he faded back as far as 15 and 20y behind the line of scrimmage, picked out his receivers and completed his passes. And when he couldn't find anyone free, he ran with the ball. On two successive plays he gained 34 yards on runs, nearly twice as many as the rest of the team would make on the ground all day. He mounted a drive that carried the Eagles 64y in five plays, and seemed headed for the tying touchdown when the halftime gun went off. In all, Davey had completed 11 passes for 112 yards in the first half. That was only a warmup for what was to come. He continued his assault in the second half. Despite the growing pressure being put on him by the Redskin linemen, Davey managed to connect on passes with ridiculous ease. He passed wide to the side and he passed deep; he threw from behind his own goal line and he threw on the dead run, riddling the Redskins defense with his slingshot passes. He was the little David against the Goliaths of the league, a sprite standing up against the six-foot, 230-pounders who seemed to be trying to separate his head from his shoulders Often enough they got to him and smashed the little man to the ground. But each time he would pick himself off the turf and go back to work. Every now and then a Redskin lineman would help him to his feet, apologizing for having knocked him down. Meanwhile, the Redskins, masterminded by Sammy Baugh, who had preceded O'Brien at TCU, scored on Dick Todd's plunge from the four-yard line. With Bob Masterson's kick the Redskins now led 13-0. Still, O'Brien would not quit. Playing all the way on offense and defense, he stimulated another Eagle drive. He engineered two drives in the third period, one of them for 68y in 12 plays, and another for 66y in five plays. But the Eagles still couldn't get the ball across the Redskin goal line. The Eagles' predicament looked even gloomier in the fourth quarter when Baugh, an excellent punter, quick-kicked, and the ball traveled 85 yards before it was downed on the three-yard lien. But O'Brien charged up the Eagles once more. He began pumping passes immediately. His primary target was left end Don Looney, who was to catch a record 14 passes for 180 yards during the day. In 15 plays, he drove the Eagles all the way, finally scoring with a 13y pass to FB Frank Emmons. The try for the extra point was blocked, and the Eagles trailed, 13-6. Time was running out now, but not O'Brien's courage. As soon as the Eagles got the ball again, O'Brien began one last drive that carried them down to the Redskins' 33. He was still flinging passes into the end zone, trying for the trying score while being rushed by six or seven men at once. But with 17 seconds showing on the clock, and O'Brien's endurance waning, Coach Bert Bell took him out of the game. He had played for 59 minutes and 43 seconds of a grueling football game, and he had thrown an unprecedented total of 60 passes. And not one of them was intercepted! Overall, Davey completed 33 of his passes for 316y. As Davey came to the sidelines, a dejected little figure in a mud-caked jersey with the numeral 8 on it, everyone in the ballpark stood up and cheered for his remarkable demonstration of courage and skill. Even the Redskin players openly applauded him as he walked off the football field for the last time. The Eagles were beaten, 13-6, but not vanquished. Davey's performance that day remains an indelible memory, even though most of his marks have since been erased. But the one that still stands is his 60 passes. [The record was finally broken by Joe Namath, who threw 62 for the Jets against the Baltimore Colts in 1970, three years after this story was written.]

O'Brien with his mates after his last NFL game From South Bend to Bataan

Notre Dame's Tonelli faced horrors of Bataan, refused to die

Bill Jauss, "Notre Dame News," 8/19/02

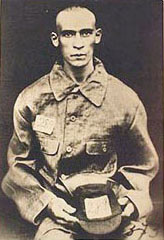

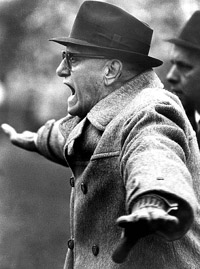

On the afternoon of Nov. 27, 1937, in South Bend, Ind., Notre Dame needs a miracle, the kind found in Hollywood screenplays, not football playbooks. It is late in the fourth quarter, and the Fighting Irish are tied 6-6 with Southern California. Suddenly, Notre Dame fullback Mario "Motts" Tonelli takes a hand-off deep in Irish territory, and the bleachers erupt as No. 58 races down the field. After 70 yards, the 5-11, 195-pound Tonelli is tackled, but he scores the game-winning touchdown seconds later.

Afterward in the Notre Dame locker room, Tonelli confesses, "I don't remember that run. I don't know just what I was thinking about, except just to run."  L-R: Mario Tonelli scores against USC in 1937 'We're in trouble,' Tonelli whispers. Instinctively, Tonelli buckles his steel helmet, ready for action. But there will be no fourth-quarter Hollywood heroics on the Bataan Death March. Unlike thousands of other young soldiers, Tonelli's tale doesn't end in a shallow, unmarked jungle grave. Perhaps it's fate. Or destiny. This year marks the 60th anniversary of, by any definition, one of World War II's most horrific tragedies and the incredible story of one football player's extraordinary will to survive. Motts Tonelli, 86, was a survivor long before the millennial trend of reality television popularized the term. The yellowed newspaper clippings in the laminated scrapbooks spread across the kitchen table in his suburban Chicago home are proof. And for the former football star and war hero, it's been that way since the beginning. At 6, he suffered third-degree burns on 80% of his body when a trash incinerator toppled onto him. Tonelli's immigrant father, Celi, a former quarry laborer in northern Italy, stonewalled a doctor's notion that his son might never walk again. He fastened four wheels to a door and taught his first U.S.-born offspring how to move about using his arms. Within months Tonelli was back on his feet, and by 1935 he was the pride of Chicago's prestigious DePaul Academy, a prep standout in football, basketball and track. Dozens of colleges courted him. After a whirlwind recruiting trip, he was sold on Southern California. But his mother, Lavinea, after a visit from Notre Dame coach Elmer Layden and a priest fluent in Italian, decided otherwise. 'You're going to Notre Dame," she said. 'It's a Catholic school, and you won't be far from home." 'And that was it,' Tonelli says, laughing. Tonelli spent three years with the Fighting Irish varsity, leading Notre Dame to the brink of a national championship in 1938. Following the College All-Star Game in 1939, he received his gold class ring, on the underside of which he had his initials and graduation date M.G.T. '39 engraved. He wore the ring proudly during a stint as an assistant coach at Providence College in 1939 and one season of pro football with the Chicago Cardinals in 1940. In early 1941 Motts joined the Army and was assigned to the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment in Manila. Although the "Pearl of the Orient' was a prewar paradise of sun-drenched tropical beauty and cold San Miguel beers, Tonelli hoped to fulfill his one-year commitment and return to his new wife, Mary, and the Cardinals by the 1942 season. Those plans were irrevocably altered in the early morning hours of Dec. 8, 1941, when Tonelli was roused from his bunk near Clark Field by an air-raid siren. At 0230 hours, a frantic trans-Pacific message had crackled over the airwaves: "Air raid on Pearl Harbor. This is no drill!' After the initial lightning thrusts of the Japanese crippled the Philippines-based U.S. Far East Air Force and Asiatic Fleet, Gen. Douglas MacArthur ordered about 15,000 American military personnel and 90,000 Filipino troops to retreat into Bataan, a steamy jungle realm of rice paddies, nipa (Asiatic palm tree) huts and colossal volcanoes, to fight a delaying action and wait for reinforcements. But with the War Department's mandate from the White House to defeat Adolf Hitler first, these ill-prepared, inexperienced troops, captured with little food and obsolete weapons, would be sacrificed to buy time for their countrymen. As a result, historians nicknamed the gallant stand on Bataan the "Alamo of the Pacific." With an empty canteen, Tonelli began the 65-mile march near Mariveles, a port on Bataan's southern tip. Through dust clouds, he spotted artesian wells bubbling with cold spring water, but he dared not stop: The Japanese savagely executed all who strayed from the march. At dusk, the parched prisoners improvised by spreading their shirts on the ground to collect the dew. "When morning came, we'd wring them out for something to drink," Tonelli recalls. At dawn, cracks of rifle fire echoed throughout the hills. Some guards pumped bullets into those unable to continue; others delivered death with samurai swords. Sympathetic Filipino civilians caught throwing food or flashing the "V for victory" sign in the direction of the haggard Americans were rewarded likewise. Japanese tanks often swerved in deliberate attempts to run over wounded GIs lying on litters. Tonelli was reflecting on his relative mortality when approached by a guard plundering the possessions of the weary, sunburned prisoners. He demanded Tonelli's Notre Dame ring, and Tonelli refused. The guard reached for his sword. Give it to him," yelled a nearby prisoner. "It's not worth dying for."' Reluctantly, Tonelli surrendered the ring. A few minutes later, a Japanese officer appeared. Did one of my men take something from you?" he asked in perfect English. "Yes," Tonelli replied. "My school ring." "Here," said the officer, pressing the ring into Tonelli's callused, grimy hand. "Hide it somewhere. You may not get it back next time." The act left Tonelli speechless. "I was educated in America," the officer explained. "At the University of Southern California. I know a little about the famous Notre Dame football team. In fact, I watched you beat USC in 1937. I know how much this ring means to you, so I wanted to get it back to you." The surreal encounter ended, and the gridiron and battlefield rivals headed their separate ways. "I always thought that someday he'd try to look me up," Tonelli says. "I guess he probably didn't make it through the war." Nearly 700 Americans and 10,000 Filipinos died on the Bataan Death March, but for those who survived, the nightmare was only beginning. Tonelli absorbed numerous beatings in three squalid prison camps over the next 2 1/2 years, but each night he would reach for the silver soap dish where he concealed his Irish ring. Each glimpse of the ring reminded him of better days and provided hope for the future. Following a hellish, 60-day journey on a filthy, cramped merchant vessel in late 1944, Tonelli was sent to slave labor camps on mainland Japan. When he arrived at Nagoya No. 7, a prison camp near the village of Toyama, in the summer of 1945, Tonelli was a 100-pound skeleton, a mere shell of the bullish fullback that once roamed Notre Dame Stadium, Soldier Field and Comiskey Park. "I felt that (Toyama) would be my last stop,' he says. "I was going to die there or be liberated." His body ravaged by malaria and an intestinal parasite, Tonelli wobbled to a table where a Japanese officer assigned prison garb and identification numbers. Tonelli glanced at his new prison number. It couldn't be. Tonelli fought to hold back the jubilant tears. Scribbled on a piece of paper was the number 58, the same number he wore throughout his football career. "From that point on," he says, "I knew I was going to make it." The atomic bomb ended the war, and Tonelli was home by October, weighing 183 pounds thanks to "a miracle of American roast beef, butter and milk," commented Chicago Daily News sportswriter Francis J. Powers.    L-R: RB Mario Tonelli, prisoner Mario Tonelli, Tonelli being interviewed It didn't take him long. Tonelli was sworn in as the youngest commissioner in Cook County history in 1946, and after a distinguished 42-year career in politics and public service, he retired in 1988. One of the estimated 1,000 remaining Bataan Death March survivors, he speaks about his wartime experiences at local schools. "Well, that's the end of the story," Tonelli says to the visitor sitting in his kitchen. "Any other questions?" "The ring. Do you still have it?" asks the visitor. "You want to see it? C'mon." He places a small, golden object in the visitor's left hand. Although worn by the effects of time, both the university seal and the inscription on the inner band remain legible. 'It's kind of worn down, isn't it?" Tonelli flashes his trademark smile. "It's over 60 years old," he explains. "Imagine what it's been through, where it's been. The history it's seen. It's been through a hell of a lot, kid, but it's still here." Just like its owner. Postscript: Mario died at age 86 about a year after the above article appeared. You Can't Quit!

Lombardi and Landry, by Ernie Palladineo (2011)

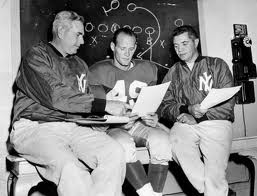

Tom Landry retired as a player to devote himself full-time to coaching the New York Giants' defense for the 1955 season while Vince Lombardi ran the offense for head coach Jim Lee Howell. As if pre-ordered by mail, Landry's defense arrived at the same time [as Lombardi's offense]. More accurately, the missing link showed up.

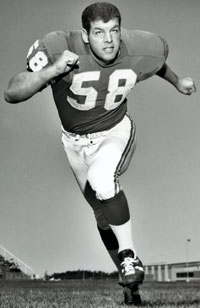

The 4-3 couldn't really work without a middle linebacker who not only went straight ahead into the hole, but who had the speed to pursue ball-carriers sideline to sideline, too. Ray Beck had done an acceptable job switching between middle guard and middle linebacker, but he got hurt in an exhibition game. Luckily, Landry had noticed this baby-faced, third-round draft pick sitting over on the offensive line. Robert Lee "Sam" Huff had been a two-way lineman for West Virginia, and a pretty good one at that. Though he always was more comfortable on the defensive front, the Giants were trying to make the 235-pounders into an undersized guard, with only limited success. "That was okay. I could play it," Huff said. "But they could run over you. I had to do everything I could to get the job done - clutch, hit a guy in the chinstrap, scratch." Landry liked the kid's mobility and his mind. A coal miner's son trying to avoid life underground, Huff was physically and mentally tough, qualities that became apparent during a senior year matchup with Syracuse, when one Jim Brown ran over the defensive tackle and knocked him out. Huff woke up moments later to a broken nose and four shattered teeth, but that didn't stop him from re-entering the game.   L-R: Jim Lee Howell, Tom Landry, Vince Lombardi, Sam Huff So they talked. "Sam, have you ever thought about playing linebacker?" Landry asked. "I could play wherever you want me." "I'd like to see what you can do at linebacker." "Fine. I'm a rookie. I'm trying to stay alive." With that exchange, a sort of evolutionary moment happened that would change the Giants' defensive look forever. Huff crossed scrimmage and, like Cro-Magnon Man morphing into Homo Erectus, rose from his three-point stance and stood up behind the defensive line. The whole world opened before him. Cue the heavenly chorus. "So now, I can see everything," Huff remembered years later. "I have terrific peripheral vision, even to this day. So now I can see everything, and boy, I made tackle upon tackle. It was the best move for me in my life. This was so much easier because I was standing up and could see everything. I could see the whole field and react to it." In an odd way, Lombardi could claim as much a part of Huff's defensive success as Landry, for it was the offensive assistant who kept Huff in camp in the first place. Frustrated by his difficulties with the pro game at guard and tired of the daily verbal goings-over Howell inflicted on him, Huff, along with fifth-round punter Don Chandler, had had enough two weeks into camp. One account indicated that Huff had overheard line coach Ed Kolman telling another assistant that Huff was "a step too slow for offensive guard" and, at 235 pounds, "too light to play defense." Part angry, part defeated, and part homesick, Huff and Chandler went to Howell's room one night, playbooks in hand. Howell was out, but his roommate, Lombardi, was there.The ensuing discussion did not go well for either player. "He called us every name in the book," Huff said. Hearing the commotion, Kolman came into the room and promised Huff he'd get Howell off his back, a promise he wound up keeping. But even that wasn't convincing enough. The two players eventually decided to head for the airport, only to have Lombardi head them off. "Now hold on!" Lombardi screamed. "You may not make this club, Chandler, but you're sure as hell not quitting on me now! And neither are you, Huff, in case you've got any ideas of running out. We've got two weeks invested in you. Now get the hell back to St. Michael's and be at practice tomorrow morning!" Lombardi did them both a favor. Chandler went on to play a decade and became Lombardi's star placekicker and punter with Green Bay's championship teams. And Huff? The move across the line would start him on a Hall of Fame career and cement his name among the most violent of middle linebackers ever to play the game. The Tao of Z

Dr. Z: The Lost Memoirs of an Irreverent Football Writer,

Paul Zimmerman; edited by Peter King (2017) The first pro football locker room I ever saw was in 1960, the Eagles-Packers NFL Championship in Franklin Field, Philadelphia. I had been with the New York World-Telegram & Sun for about six months. I had been covering high school sports and I'd worked on the night desk in the summer, before the schools started, with the Little League World Series as my only bylined piece during that period. But they wanted to see how I would handle myself in the big arena, so they sent me down to do loser's dressing room quotes for our regular pro football writer, Joe King. It was a disaster.

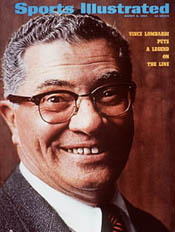

The problem was that I was spending my Saturday nights playing guard for the Paterson (N.J.) Pioneers of the Eastern Football Conference, which billed itself as either Minor League Football or the NFL's farm system. Take your pick, but in reality it was one of the many outposts of semipro football. The Packers had lost to the Eagles, but I couldn't get over the way the Green Bay middle three of Jim Ringo, Fuzzy Thurston and Jerry Kramer had crushed the center of the Eagles' defense, including the great Chuck Bednarik. The first guy I saw in the Packer locker was Thurston. "Hey, great job against Eddie Khayat," I blurted out. His eyes narrowed. He had just lost the biggest game of his life. Was this some kind of con job? "Thanks," he said. I'd been knocked out by the smoothness with which they called their in-line audibles among themselves, their change-ups. I complimented him on it. By now Kramer had joined our little group. "You're a writer?" he said. I brushed it off. I told him that we were having trouble calling our audibles on the Paterson Pioneers. I asked them how they called them. "Hey, Jim!" he called over to Ringo in the next locker. "I want you to meet this guy." So for 10 minutes or so, they laid it out for me, who made the call in each situation, how they handled the dummy calls … and the Eagle tackles, Khayat and Jess Richardson, which they most definitely had done. The Packers ran for 223 that day. It was a nice friendly little group, and I was thinking, Wow, it sure is great covering an NFL locker room. Then I noticed that the room was emptying. My page of quotes for Joe King was blank. Oh oh. I excused myself. I looked for Bart Starr. He was gone. They were helping Paul Hornung into his sportcoat; he had suffered a pinched nerve in his shoulder. "How's the shoulder?" I asked him. "It hurts," he said. And he was gone. I searched for Vince Lombardi. He was on his way out the door, wrapping a muffler around his neck, for the cold. "Uh, coach," I said. "I said everything I had to say to all the writers," he said. "We needed more time, OK?" And he was gone. Everybody was gone except for a few stragglers, some equipment men loading stuff into bags. I made my way up to the press box, which was on an odd angle. It looked as if a strong wind might blow it, plop, right onto midfield of the venerable stadium. It matched my own feeling of impending doom. Put a little pencil mustache on Humphrey Bogart, and I'd hire him to play Joe King in the movie version. Cigarette hanging out of the side of his mouth, a bottle of Heineken's close by his left hand, grey fedora pushed back on his head, with his press ticket in the band, Joe was everyone's idea of what an old-time sportswriter should look like. I stood behind him and watched him type. "OK, waddya got?" he said. "What do you want?" "Gimme Lombardi." "He was on the way out. He said they needed more time." "And … AND?" "And that's what he said." "OK, gimme Hornung. How about the shoulder?" "He said it hurt." By now Joe had stopped typing. He was as fascinated by the horror of this as I was. "What did Starr say?" he said so softly that I could barely hear it. "Nope, I missed Starr," I mumbled. Joe took his hat off and laid it on the desk. He turned in his seat and stared at me. "Son, what DID you get?" "Well, I talked to Kramer and Thurston and Ringo about how they called their audibles, and …" He waved me away, as one would dispel a bitter memory. "Out, son. OUT! GET OUT! "Jack … Nat … catch me up on Lombardi … can you give me a little Starr … Just a graf or two … I SAID OUT OF HERE, KID! OUT!" It took me two years before I saw the inside of a professional locker room again. ...    L-R: Paul Zimmerman, Fuzzy Thurston, Jim Ringo One of the first games the New York Post sent me out to cover, all by myself, was Green Bay at Chicago in 1966. I set up my audience with Lombardi well in advance for a Tuesday actually. That's how nervous I was. I took a cab from the airport and got there at lunchtime, an hour and a half before my appointment with the coach. ... He was cordial. He asked me where I grew up and where I had played. I told him, adding that in high school we had scrimmaged against the team he was coaching, St. Cecilia's in Englewood, N.J., and that I had very fond memories of his power sweep. He threw back his head and laughed. Then he called in his line coach, Phil Bengtson, who'd had the same position at Stanford when I was there, just to check me out. Bengtson, God bless him, if it would have been England, he'd have been knighted. I'm sure he didn't remember a thing about me, but just to be a mensch, he gave it the, "Hey, nice to see ya … how ya been … I see that you've picked up a little weight," and so forth. Whew. I had passed muster. So we chatted for a while, and then Lombardi got real serious and said, "You're a young writer, you're from New York, I'm going to give you a good story for your paper." Thump, went my heart, thump thump. "This is the game where I find out about my million dollar rookies, Grabowski and Anderson. All that money we paid them (combined contract a cool million, record numbers in those days) … I've got to know whether they can play." And on and on in that vein, until I am so feverish to call my paper and tell them to hold the back page because I've got a scoop from Lombardi, that I can hardly bear it. And I gave them the message, and they held the back page and next day's streamer, in red, blared, LOMBARDI TO UNVEIL MILLION DOLLAR ROOKIES.

P.S: Neither one played a down.    L-R: Vince Lombardi, Jim Grabowski, Donny Anderson "Welcome to the club," he said. "Easy," he said. "He knows that Halas gets everything clipped from the out of town papers. So he might as well plant something, just to give him another thing to worry about."... Obviously, it would be a defensive story for me. In the Green Bay locker room, Lombardi was sitting on a little counter in front of the cage where they handed out equipment, in the center of a cluster of writers in overcoats and hats. Steam was rising. They were interviewing the coach, but it looked like they were cooking him. I waited my turn and then asked, "What was your theory in defending Sayers?" "Force him back into the flow of traffic,’" Lombardi said, "cut off his escape. It's a theory as old as football itself." Fine. I had my Lombardi quote. It was time to talk to the players. The Packers locker was next to the equipment alcove, through an open door. Dave Robinson, the strongside linebacker who had had a good day, was about 10 feet in. I introduced myself and asked him, "What was your theory in defending Sayers?" "Wait a minute! Wait a minute!" Lombardi shouted from the next room. Both rooms fell silent. I looked through the door, and he had popped up from the center of his steam table and was pointing a finger in my direction. Everyone was staring at me. "The same thing," he said. "You asked me the same thing, in exactly the same words. What's the matter, didn't you believe me?" A few of the players were hiding their faces, so the coach wouldn’t see them chuckling. Robinson had a big smile on his face. He waved me to follow him around the corner. As I went, I heard Lombardi telling the writers, "The exact same thing … see that guy there … first he asks me about Sayers, then he goes in and asks them the same thing…" It Was the Red Candles Runnin' with the Big Dogs: The Long, Twisted History of the Texas - OU Rivalry,

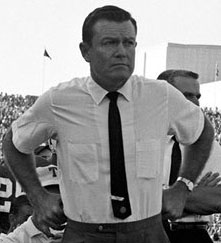

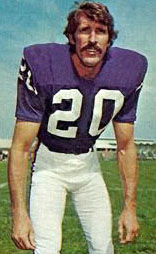

Mike Shropshire (2006) Darrell Royal's Longhorns and Bud Wilkinson's Sooners prepared for their annual clash in 1963. The OU-week atmosphere around Austin was bubbling from simmer to full boil. Students were resorting to voodoo, if that's what it took to beat the Sooners. Madam Hipple, an Austin psychic who had enjoyed the full faith of UT coeds for two generations, had suggested in 1940 that Texas could upset Texas A&M if Austinites would burn red candles. It worked, too, and twenty-three years later, the candles were gleaming again across the Texas Hill Country. Royal remained dubious. On his weekly TV show, the coach said, "It's going to take more than red candles to stop [OU RB] Joe Don Looney." Now Royal didn't say so, but he was suspicious that while the candles might not do the job, he had a couple of players on his defense who absolutely could.

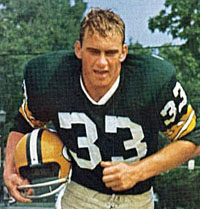

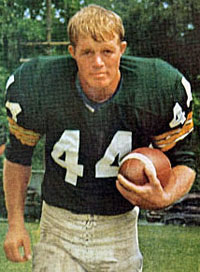

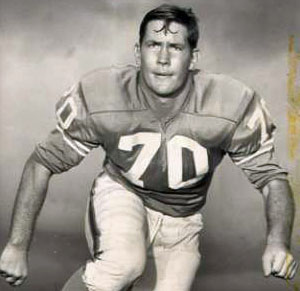

L-R: Darrell Royal, Joe Don Looney Tackle Scott Appleton, Royal and his assistants realized, would be a force that could defeat any OU lineman. He was a kind of player seldom seen on college playing fields those days - the product of a small town. Because good athletes in little schools would play every sport, including tennis, and then work for the volunteer fire department on weekends, the small school could not concentrate on being a good sports school. Plus, all of those hick programs had crappy weight programs.

Appleton was the product of Brady, Texas, which is the site of the state's finest and best goat cookoff. If deer hunting were an Olympic event, Texas could secede from the union and win the gold medal every four years, and if the Pro Football Hall of Fame is in Canton, Ohio, then the deer hunting Hall of Fame could only be situatedin Brady. Pickup trucks in the town are adorned with antlers, inside and out, and [LB] Pat Culpepper recalled visiting the area with Appleton. "Scott stopped his car and shot a deer right off the highway," Culpepper said, "and a game warden saw that and chased us all the way to Junction." ... But with OU week on the horizon, Appleton converted his enthusiasms to Sooners hunting was setting some pregame traps. "Mike Campbell [UT defensive coach and maestro of tactical intricacies] had prepared his game plan for the OU game and down it onto a blackboard before a team meeting," Culpepper said, "and Scott came in before the meeting, erased the whole scheme, and replaced it with the Brady High School defense, with Appleton at middle linebacker."    L-R: Pat Culpepper, Scott Appleton, Tommy Nobis "Bowlegged, but my God he was fast," recalls Culpepper, "and ever faster than in his sophomore season, before he had all those knee operations that would slow him down as a pro. ... OU really had no inkling of how good Tommy Nobis was. After the season, pro scouts told us that they all thought Tommy was better than Dick Butkus." The Texas team that put on its coat-and-tie road outfit and boarded the charter airliner for the one-hour flight up to Dallas was prepared, but scarcely brimming with confidence. ... Friday night before the game, the Texas players attended the movies - those being films of the Oklahoma football team. These film sessions were for players only, since the coaching staff was scattered throughout the Dallas-Fort Worth area scouting Friday-night high school football talent. After absorbing the OU films, the players strolled the front sidewalks of the Melrose Hotel. ... The team then retired for the night, where [team trainer Frank] Medina, no longer the brutal whip-wielding czar of team toughness, had prepared for bedtime snacks. ... The game-day morning routine went as usual ... The players climbed on the buses for the trip to the State Fair grounds and the Cotton Bowl. Every player now realized that he would soon be involved in two fights, one against the crimson-shirted Okies and another, the harder battle, being the one within, in which the player had to reject the all-too-human instinct to quit when the body transmits signals that it can take no more. Finally, game time arrived. Texas took the opening kickoff and right away took advantage of the weak-side option play that Royal had installed especially for the anticipated froth-around-the-lips aggressions of the OU defense. ... Looney was a diesel locomotive of a ball carrier, not a high-stepping gazelle. The Texas scheme was to not attempt a tackle above the ankles. It worked. Looney was tripped play after play. ... UT led 14-0 at halftime ... Their first-half success triggered some trash talk directed toward the frustrated Sooners. UT captain David McWilliams put a stop to that. "Shut the hell up," he chastised a teammate. "You're liable to wake them up." The awakening never took place, and Texas won, 28-7 - the team's most heralded postwar victory, and probably the biggest in the history of the school. Afterward, Royal could have viewed the stats and credited the win to his passing attack. Texas threw the ball exactly three times (completing one) against Oklahoma - definitely Darrell's kind of game. Looney offered this explanation: "They kicked the shit out of us. I think we were too cocky."    L-R: David McWilliams, Staley Faulkner, Bud Wilkinson Any respect that Texas, now number one in the land, might have earned in that Dallas coup didn't last long. The Monday after the OU game, Sooners coach Bud Wilkinson kicked Looney off the team. It was cited that during the off week before the prior game Looney had fought with a student in practice and that Looney had mostly been screwing off in practice, anway - thus creating bad morale. The implication was that the team Texas had beaten was not the real OU. Bud Wilkinson said so himself ... "Obviously, they [UT] are a better team, but the disappointing fact remains that we failed to use our best abilities. ..." "I purposely flunked the entrance exam."

It's Only a Game, Terry Bradshaw with David Fisher (2001)

At Woodlawn (High School in Shreveport LA) the QB playing in front of me was a high school All-American named Trey Prather. But rather than being discouraged because I wasn't the varsity QB, and pouting, I practiced as hard as I could, believed in my ability, and waited for my chance. Coach (Lee) Hedges was always supportive. ...

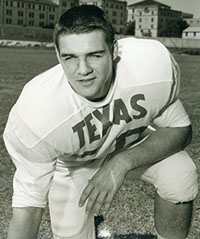

I was our starting QB my senior year. I didn't have a lot of experience, but I had raw talent and a rocket arm, so I attracted the attention of college scouts. More than 200 colleges offered me track scholarships [Terry broke the national high school record for the javelin throw.] - I even got track scholarship offers from a school in Europe - but as it seemed pretty certain no one was about to start a professional javelin-throwing league, I knew that if I was going to have a career in sports it was going to be in football. Among the few major colleges to offer me a football scholarship was Baylor University. Baylor is a fine Baptist university in Waco, Texas, whose motto is Pro Ecclesia, Pro Texana, which roughly translates, "Terry can't even understand the motto, so no way is he going to go there." But I did go there for a visit, and it was an impressive place. ... During my campus visit I spent time with a player I knew from high school - and I was shocked at what I saw: Shocked! We were in his room, and from beneath his bed he pulled out a six-pack of beer and offered me a drink! I had never had an alcoholic drink in my life, and I wasn't about to attend a Christian college where football players kept alcohol under their beds. ...    L-R: Trey Prather, Terry Bradshaw @Woodlawn, Terry Bradshaw @ Louisiana Tech Just about everybody I knew - as well as a lot of people I didn't know - wanted me to go to LSU. I didn't know how to tell them that I didn't feel comfortable in Baton Rouge, so I purposely flunked the entrance exam. I have never much liked people who make excuses for their failures. I am not claiming that I could have passed that exam easily if I had wanted to go to LSU. I'll never know if I could have passed it; I know I didn't study for it, I didn't care about it, and I definitely didn't want to go to LSU. And I also didn't pass the test. ... To qualify for a scholarship you had to get 16 - when I took the test a second time I got 15. Instead of being upset about it, I was relieved. All it meant to me was that I couldn't go to LSU. Of course, I absolutely could not imagine how failing that test would affect my life. If I had known how it would damage my reputation, how it would cost me a fortune in endorsements, how embarrassing it would be, I would have put some real effort into studying, and I could have failed that test with style! Instead I attended Louisiana Tech University in Ruston, LA. My high school preparation began paying big dividends as I sat on the bench for two years. ... yet I continued to believe without any doubt that I was on my way to a career in professional football. ... At the end of my sophomore year I began to see my dream slipping away from me. I don't quite remember how it happened - my father might have made the phone calls - but we got in touch with a coach at Florida State University who invited me to transfer. My older brother, Gary, and I got in the car and started driving to Tallahassee to meet the coaching staff. But before we could get there, the coaches at Tech found out we were on our way and threatened to inform the NCAA that FSU was tampering. By the time we got to Tallahassee, no one on that coaching staff would even meet with us. Freshman QB at Oklahoma

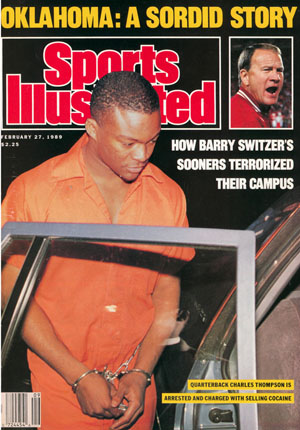

Down & Dirty: The Life and Crimes of Oklahoma Football, Charles Thompson & Allan Sonnenschein (1990)

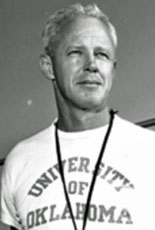

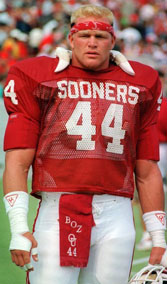

Charles Thompson came to Oklahoma in 1986 ready to redshirt for a year before replacing Jamelle Holieway as QB of Barry Switzer's powerful wishbone offense.

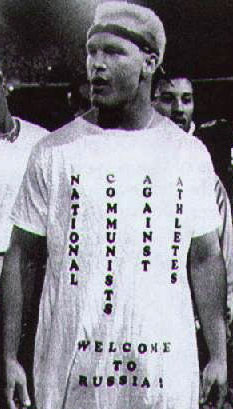

The wishbone is a distinct, high-scoring offense that requires quality athletes to run the ball. ... A wishbone QB takes a lot of pounding because he is moving or running with the ball on every play. He must possess speed and quickness, not a great passing arm. ... It seems that most great wishbone QBs and RBs are black, and at OU the coaches said, "If he's not black, don't bother recruiting him." ...As a redshirt ... I demonstrated my commitment on the practice field, in scrimmage against the varsity defense. I wanted to show what I had against the number one college defense in America. All I was to them was "freshman meat." There was a rule that they were to take it easy and not hurt the QB, but those animals never obeyed it. In my first scrimmage, I had optioned down the line, looking to cut inside when I saw an opening. Boom, the hole closed as fast as it had opened and I got hit with what felt like a Mack truck. I probably weighed 155 and all of it went flying back five yards, my helmet covering my face and my eyes rolled up into my head. When my senses returned to this world I looked up into the eyes of the modern day road warrior, Brian Bosworth, "The Boz." He stood over me with a grin on his face that said: "Welcome to college football." ... Off the field and away from the cameras and crowds, Brian was a different person - very private, avoiding intimate conversations, protective of his friends. He helped me adjust to college football life. ...    L-R: Charles Thompson, Brian Bosworth, Keith Jackson Keith taught me all I needed to know about "freaking" - dealing with boosters and alumni when you attain a certain level of popularity and stature and they want to court you. ... Freaking with boosters and alumni meant they showered you with gifts and money, and sometimes drugs. Former OU RB Stanley Wilson claimed that his cocaine habit was fed by OU boosters. ... I watched Keith do favors for boosters and receive nothing in return. An example of this occurred when he introduced me to Jackie Cooper ... Cooper owned several automobile dealerships in the Oklahoma City-Norman area. ... Keith and I were pretty wasted by the time we got to Jackie Cooper's place. We had stopped off on our way at a place called "F.O.P.," where we had drinks with a detective and several other Oklahoma City police officers. When I walked into Cooper's I saw Barry Switzer and tried to sober up. I think Switzer was wasted by that time and didn't notice my condition; at least he didn't say anything. After the show Jackie Cooper invited Keith and me to dinner at Juniors, a fancy restaurant in the city. ... I was getting shitfaced and thought about seeing Switzer earlier in the evening. I told Keith that I wanted to leave and got up and went to the bathroom. Cooper joined me in the men's room and asked me if I had a car. When I said I didn't he said, "Well, why don't you get my phone number from Keith and give me a call? You come down to my lot and pick something out. And don't worry, we'll work something out." I wasn't sure about what he meant by working it out, but I figured that I had nothing to lose by calling, so in a few days, I did, and made arrangements to visit the lot. Cooper seemed happy to see me and we discussed how I would pay for a car. I knew it would be expensive because he had classy cars on the lot - BMWs, Mercedes, Jaguars. The car had to be bought in someone else's name, usually a family member. ... Once that was arranged the bank would approve a loan, but he would have someone take care of the payments. ... As the year went by Switzer saw and appreciated how much I was developing as a QB ... the first Christmas I was at OU, when I wanted to visit my mother in Dallas, he paid for the airline ticket. He paid for several pairs of Nike shoes I wanted, and when I needed a few extra dollars he was generous. I don't know if the money was his or the university's, but whether it was 50, a 100, 250 dollars, he came up with it. He knew everybody, or so it seemed, and when a concert was sold out in Oklahoma City he was always able to get tickets. ... In 1986 the NCAA went all out in their crackdown on steroids. Boz and a reserve guard ... were tested before the Orange Bowl and found guilty of using steroids. As far as the Bowl game went this didn't hurt OU, especially considering the great game played by Dante Jones at Bosworth's position. What made it a big issue was how the Boz reacted. He took a f***-you attitude toward the NCAA. He thought the NCAA was hypocritical and challenged the accuracy of the steroid test. ... Relegated to watching the Orange Bowl on the sidelines, Bosworth wore his own NCAA T-shirt, which read: NATIONAL COMMUNISTS AGAINST COLLEGE ATHLETES. Switzer and Donnie Duncan, OU's AD, were furious and ordered him to get rid of the shirt or leave. This was on national television and Barry Switzer was not going to let Brian Bosworth steal his thunder. It was the final cut that severed their relationship. Although Boz had another year of eligibility, he chose to go to the NFL. Brian wasn't the only OU player to use steroids. I knew first-hand of five players and was told by others that there were about a dozen. It's interesting that the players I knew who were using steroids were all white.   It's All Over

Boys Will Be Boys: The Glory Days and Party Nights of the Dallas Cowboys Dynasty,

Jeff Pearlman (2008) Michael Irvin knew he was screwed. There, dangling in his right hand, was a pair of silver scissors, bits of shredded brown skin coating the tips. There, clutching his own throat, was Everett McIver, a 6-foot, 5-inch, 318-pound hulk of a man, blood oozing from the 2-inch gash in his neck. There, standing to the side, were teammates Erik Williams, Leon Lett, and Kevin Smith, slack-jawed at what they had just seen.

It was finally over. Everything was over. The Super Bowls. The Pro Bowls. The endorsements. The adulation. The dynasty. Damn - the dynasty.   L: Michael Irvin; R: Everett McIver The greatest wide receiver in the history of the Dallas Cowboys - a man who had won three Super Bowls; who had appeared in five Pro Bowls; whose dazzling play and sparkling personality had earned him a devoted legion of followers - knew he would be going to prison for a long time. Two years if he was lucky. Twenty years, maximum.

Was this the first time Irvin had exercised mind-numbing judgment? Hardly. Throughout his life, the man known as The Playmaker had made a hobby of breaking the rules. As a freshman at the University of Miami fourteen years earlier, Irvin had popped a senior lineman in the head after he had stepped in front of him in a cafeteria line. In 1991, Irvin allegedly shattered the dental plate and split the lower lip of a referee whose call he disagreed with in a charity basketball game. Twice, in 1990 and '95, Irvin had been sued by women who insisted he had fathered their children out of wedlock. In May 1993, Irvin was confronted by police after launching into a tirade when a convenience store clerk refused to sell his eight-year-old brother, Derrick, a bottle of wine. ... Most famously, there was the incident in a Dallas hotel room on March 4, 1996 - one day before Irvin's thirtieth birthday - when police found the Plamaker and former teammate Alfredo Roberts with two strippers, 10.3 grams of cocaine, more than an ounce of marijuana, and assorted drug paraphernalia and sex toys. Irvin - who greeted one of the on-scene officers with, "Hey, can I tell you who I am?" - later pleaded no contest to a felony drug charge and received a five-game suspension, eight hundred hours of community service, and four years' probation. But stabbing McIver in the neck, well, this was different. ... Was he loyal to his football team? Undeniably. Throughout the Cowboy reign of the 1990s, which started with a laughable 1-15 season in 1989 and resulted in three Super Bowl victories in four years, no one served as a better teammate - as a better role model - than Michael Irvin. He was first to the practice field in the morning, the last to leave at night. He wore weighted pads atop his shoulders to build muscle and refused to depart the complex before catching fifty straight passes without a drop. Twleve years after the fact, an undrafted free agent QB named Scott Semptimphelter still recalls Irvin begging him to throw slants following practice on a 100-degree day in 1995. "In the middle of the workout Mike literally threw up on himself as he ran a route," says Semptimphelter. "Most guys would put their hands on their knees, say screw this, and call it a day. Not Michael. He got back to the spot, ran another route, and caught the ball." ... And yet, there Michael Irvin stood on July 29, 1998, staring down at a new low. The scissors. The skin. The blood. The gagging teammate. That morning a Dallas-based barber named Vinny had made the two-and-a-half-hour drive to ... Wichita Falls, Texas, where the team held its training camp. He set up a chair inside a first-floor room in the Cowboys's dormitory, broke out the scissors and buzzers, and chopped away, one refrigerator-sized head after another. After a defense back named Charlie Williams finished receiving his cut, McIver jumped into the chair. It was his turn. ... In 1993 the San Diego Chargers signed McIver as a rookie free agent. He was cut several months later, signed by Dallas, and placed on the practice squad. From August through December, McIver was a Cowboy rookie scrub, forced to sing his fight song and pick up sandwiches from the local deli and call teammates "sir" and "mister ... Yet after a rough start, McIver's career picked up. He joined the New York Jets in 1994 and later spent two productive years in Miami ... With the Cowboys struggling behind an aging, oft-injured offensive line, team owner Jerry Jones tossed a five-year, $9.5 million contract McIver's way. The lineman had left Dallas as a joke and five years later was now returning as a potential cornerstone. ... Jones said ... "We're thrilled to have him here." Michael Irvin, however, wasn't thrilled. As far as he was concerned Everett McIver was simply the same nobody from earlier days. ... In 1997 the once-mighty Cowboys had experienced one of their worst seasons, finishing 6-10 and missing the playoffs for the first time in seven years. ... the Cowboys ... had spiraled out of control off of it. Drinking. Drugs. Strippers. Prostitutes. Orgies. ... For a hypercompetitor like Irvin, the losing was too much. The man who was all about devotion to the game had turned bitter. He was well aware that these Cowboys were not his Cowboys. So when Irvin walked into that room and saw McIver in the barber's chair, something inside snapped. "Seniority!" Irvin barked. McIver didn't budge. "Seniority!" Irvin screamed again. "Seniority! Seniority! Punk, get the fuck out of my chair!" "Man," said McIver, "I'm almost done. Just gimme another few minutes." Was Everett McIver talking to Irvin? Was he really talking to Irvin? Like ... that? "Vinny, get this motherfucker out of the chair," Irvin ordered the barber. "Tell his sorry ass to wait his fuckin' turn. Either I get a cut right now, or nobody does." Standing nearby was Erik Williams, McIver's fellow lineman. "Yo, E," he said to McIver, "don't you dare get our of that chair. You're no fuckin' rookie! He can't tell you what to do!" Sensing trouble, the barber backed away from McIver's head. McIver stood and shoved Irvin in the chest. Irvin shoved back. McIver shoved even harder, then grabbed Irvin and tossed him toward a wall. ... Lett, the enormous defensive lineman, tried separating the combatants. It was no use. ... In a final blow to harmony, McIver cocked his right fist and popped Irvin in the mouth. "I just lost it," said Irvin. "I mean, my head, I lost it." Irvin grabbed a pair of scissors, whipped back his right arm, and slashed McIver across the neck. ... McIver let loose a horrified scream. "Blood immediately shoots all over the room," says Smith. "And we're all thinking the same thing - 'Oh, shit.'" For a moment - as brief as a sneeze - there was silence. Had Michael Irvin ... stabbed a man ... in the neck? ... Then - mayhem. The Cowboys' medical staffers stormed the room, past a dumbstruck Irvin, and immediately attended to McIver. As their bloodied teammate was whisked away, none of the lingering Cowboys knew the extent of the damage. Was McIver in critical condition? Would he live? Either way, every single man in the room had to have understood that this was more than just a fight. The storied Dallas Cowboys of the 1990s - the organization of pride and honor and success; the organization whose players would never dare hurt one another; the organization that dominated professional football - was dead and buried. How in the world had it come to this? The Black and Blue Division

Black & Blue: A Smash-Mouth History of the NFL's Roughest Division, Bob Berghaus (2007)

The NFC Central was created on November 30, 1966, when the NFL split into four divisions for the first time ... The division had the two most recognizable coaches in George Halas and Vince Lombardi. Halas had been around since the inception of the Bears as an owner, player and coach. To many it seemed as if no major decisions in the NFL were made without the approval of the Papa Bear. "We were playing the Bears at Wrigley Field and there was snow all over the field and everyplace," recalled former Lions MLB and Hall of Famer Joe Schmidt. "We lost the game 3-0. We're skating around there and (Chicago halfback) Willie Galimore is running all over the place. So I tackle him one time and I just happened to look at his shoes and he had his cleats off; he just had the iron pegs. So I jumped up and called timeout and called the official over and told him this is illegal, that he can't have this. So he got up and ran off the field. I said, 'I want to show you this and he's standing behind Halas.' "The official says, 'George, we want to see Galimore's shoes, and George says his shoes are OK. I said bullshit he's got his cleats off and he's running all over the place. I said dammit these shoes are illegal and George says, 'I want to tell you guys his shoes are OK and both of you guys better get the hell out there and get the game going out there.' "The official says, 'Come on, kid, let's go. I'm not going to argue with him.'" Schmidt chuckled as he told the story. "George carried so much weight that he practically could convince everybody what to do and how to do it."    L-R: George Halas, Joe Schmidt, Willie Galimore What also went on was a style of football loved by purists and played by people who gave every ounce of blood and sweat they had. The only thing that could get Nitschke and Butkus off the field was a stretcher. Bill Brown and Dave Osborn, the running back tandem for the Vikings, would rather run through people than around them. Joe Kapp, the QB on the Vikings' first Super Bowl team, was the same way. It was the mindset of that team, of the entire division. "We had a guy by the name of Bobby Bryant who was our corner," said Wally Hilgenberg, who started in all four Super Bowls for Minnesota. "Bobby was about six-foot one and 167 pounds and I can tell you that on two different occasions after he made a tackle he came over to me and said, 'Wally, my shoulder's out, put it back in.' And his shoulder was literally dislocated and I would jerk on it, pull down and it would pop back in. He would never leave the field. Today these guys get a little ding and they don't want to play for two weeks." ... Hilgenberg ... was an All-American LB. "My brother was an assistant coach at the University of Iowa when I was playing for the Hawkeyes," said Hilgenberg. "The summer of my rookie year I went to the college all-star football game. The night before the game my brother and I were talking on the telephone, talking about the all-stars, the 1964 All-Stars playing the 1963 World Champion Chicago Bears." During the conversation Hilgenberg was told by his brother to make sure that he opened up the game with a good lick on the player lined up opposite him. "I'm playing LLB and we lose the toss and we kick off and the ball is on about the 30-yard line," Hilgenberg recalled. "The Bears come out of the huddle strong on my side and number 89 (Mike Ditka) walks to the line of scrimmage. I'm this rookie LB and just before the snap, I kind of drop my shoulder a little bit and as soon as the ball was snapped I threw a forearm, hit him on the chin. I knocked his head right straight back, really hit him hard. "He just stood there after I hit him and grabbed me and pulled me in and looked straight at me and said, 'You want to play rough, huh, rookie?' And I said to myself, 'Oh, no, I just made him mad.' He kicked my butt the whole game. It had been the biggest battle ever in my life up until that time, and it was funny. I knew after the game I had got my butt kicked. After the game he came up and said, 'You did a good job, kid. I'll see you around. You'll make it in this league.' "Well, it was just a real encouragement to me. I knew he didn't have to tell me that."    L-R: Bobby Bryant, Wally Hilgenberg, Mike Ditka |