|

Scott Brings Alabama to Power

Century of Champions: The Centennal History of Alabama Football, Wayne Hester (1991)

"Graveyard of Coaches" Woody Hayes and the 100-Yard War, by Jerry Brondfield (1974)

The triple-decked gray concrete structure [Ohio Stadium], built in about a year and a half, was dedicated in 1922. It held 65,000 ... It was the first of the nation's huge, modern stadiums, the first built since Harvard's and Yale's ... It launched the 1920s boom in college ball parks that had all the biggies following the Buckeye lead.

What it also led to at Ohio State was something that would be called the "Graveyard of Coaches." Dr. John Wilce, producer of the Buckeyes' first champion, first All-America and first conqueror of Mighty Michigan, continued to be a winner but couldn't whip Michigan as often as the locals would like. Beating Michigan was the eleventh commandment, losing to Michigan was the cardinal sin. By the late 1920s it was obvious Michigan had lost his desire to continue with pressure football and wanted to spend more time in medicine. He resigned after the 1928 season. L. W. St. John, the Ohio State athletic director, immediately got a tip from Major John L. Griffith, the Big Ten commissioner. He knew a candidate for the job who was really interested. "Like who?" asked St. John.

"Knute Rockne." St. John ... calmly told Griffith he was out of his cotton-pickin' mind, or whatever was the 1928 equivalent, but Griffifth knew what he was talking about. Notre Dame's famed coach somehow thought he'd climbed all the available mountains with the Irish and was looking for a new peak. Rockne and St. John went into a long huddle. After about four hours he agreed to take the job - but only if no word was mentioned until he had a chance to get back to South Bend and ask Notre Dame officials to let him out of his contract. It was all set.

No one knew how it happened, but there was a leak. Notre Dame officials heard of it, and when Rock got home he knew there was no way they'd let him out of his contract. Those were the days when coaches felt impelled to honor those things. Notre Dame talked Rockne into staying on and Ohio State lost a chance to lay forever the Coaches' Graveyard ghost that would soon take residence in the huge, cavernous stadium alongside the Olentangy River.

Instead of Rockne, the Buckeyes got one of Wilce's assistants, a solid and capable man named Sam Willaman. Unfortunately, a nickname came with him: "Sad Sam" Willaman. He had that kind of face and manner. He also was one fine football coach and never had a losing season. But in five years he couldn't wrap up a Big Ten title. There were years when he lost only one game. The one game always seemed to be to Michigan. Alumni discontent, student discontent and a generally sour interview by the statewide press convinced Michigan. He packed it in.

Francis Schmidt instructing the Buckeyes Okay, fans said, let's get somebody with imagination, with zest and zeal and anything else beginning with Z. So, St. John got it for them. He got the zaniest, maddest, most imaginative football coach ever to hit the Big Ten, and the record still holds. He got the Buckeyes Francis Schmidt from Texas Christian, and it was Schmidt who launched Ohio State's modern era of football eminence. Schmidt was a World War One bayonet drill instructor with a loud, raucous and colorful approach to the English language, the likes of which had never been heard on this serene and conservative campus. It had really taken Schmidt only one year to enrapture Ohio State fans for what was predicted to be forever. At his first football banquet after a sensational first season capped by a glorious 34-0 shellacking of Michigan, Schmidt, in bayonet drill tones, bawled forth two classic and historic comments. "Let's not always be called Buckeyes," he brayed. "After all, that's just some kind of a nut, and we ain't nuts here. [A debatable claim.] It would be nice if you guys in the press out there would call us 'Bucks' once in a while. That's a helluva fine animal, you know." Francis Schmidt, despite his individual brilliance, coached football in a perpetual ambiance of frenzied chaos. His staff was in a limbo of misdirection and uncertainty. Nobody knew from one day to another what the hell the mad genius was going to do. He heaped scorn and ridicule on his players and they hated him. There was open dissension. And after a couple of years the opposition began to catch on to his pyrotechnic style.

Then, like other coaches before him, Francis Schmidt fell victim to the Michigan bugaboo. After four straight Buckeye victories, Michigan came up with a back named Tom Harmon, and in 1938, 1939, and 1940, Ohio State dropped three in a row. ... Once again in Columbus, mutinous fans were getting out a plank for a Buckeye football coach. Francis Schmidt knew the Athletic Board was debating his future. He was the kind of man who'd rather die than be fired, so he quit before the board could act - as it certainly would have done. The board also accepted resignations of Schmidt's five assistants, two of whom would later make names for themselves elsewhere: Sid Gillman at Cincinnati and later in the pros; and Gomer Jones, who would become the architect of Bud Wilkinson's great lines at Oklahoma ... When news photographers came around for a going-away photo, Schmidt, blatantly sarcastic to the end, told them, "You guys have dozens of my pictures in your files. Just dig out one of them and use it. And while you're at it, underneath it just say: 'Rest in peace.'" Three years later, at Idaho, he died of a heart attack. Some say a broken heart. Nearly College Teammates Too

Football: The Greatest Moments in the Southwest Conference, Will Grimsley (1968)

A couple of years ago sportswriters of the Southwest Conference were called upon to vote for the greatest football players to perform in the league over the last twenty years, or since World War II - an All-Era Eleven, so to speak.

The No. 1 choice was Doak Walker, brilliant backfield star at Southern Methodist University in 1945-49. Chosen in the same backfield, close to Walker in the voting, was Bobby Layne, who quarterbacked the rampaging Texas teams in 1944-47. Layne and Walker were teammates on the Highland Park High School team in Dallas - Layne a year ahead. They were the closest of friends who held each other in the highest respect and admiration. They went into the U. S. Merchant Marine together and came out at the same time. Only a quirk of fate kept them from playing on the same college team.

Bobby helped lead Highland Park to the bi-district title in 1942 and to the state high school semifinals in 1943. Upon graduation, he moved in with an uncle, a strong supporter of the Texas Longhorns, and played freshman varsity with Texas in 1944, while wartime restrictions against freshman play were waived. Walker, with another year at Highland Park, meanwhile led his team to the state high school finals.

When Doak graduated from high school in 1945, the war was still in progress. He and his pal, Bobby, joined the U. S. Merchant Marine. The war suddenly took a quick and favorable turn, and their service was brief. On the last Saturday in October, 1945, Bobby and Doak reported to New Orleans to receive their discharges from the service. It was a coincidence that their longtime friend and former coach at Highland Park High, H. N. (Rusty) Russell, also was in New Orleans on another mission. Rusty had moved in as assistant coach at Southern Methodist and the Mustangs were in the Crescent City for a game with Tulane. There was a happy reunion.

Also in New Orleans at the time was Blair Cherry, assistant to Coach D. X. Bible at Texas. Cherry was scouting SMU for the next week's game against his Longhorns. He was happy to see Layne but happier to see Layne's young friend and ex-teammate, Walker, widely sought by all Southwest Conference schools.

"Maybe we can get that boy to come to Texas," Cherry confided to Layne.

"Perhaps," said Layne, hopefully.

Doak was not committed but was leaning heavily toward his old high school coach, Rusty Russell, and his hometown university, SMU. Russell knew he couldn't dissuade Layne from returning to Texas but he hoped to keep Bobby from influencing the Doaker, and, somewhat ambivalently, he gave the two boys tickets to the SMU-Tulane game.

L: Bobby Layne, Texas; R: Doak Walker, SMU It was almost a fatal blunder. SMU played miserably, losing to Tulane 19-7. After the game, Layne said to Doak, "You better come to Texas with me. Let's go over and talk to Coach Cherry."

"Okay," Walker said, his mind not fully made up.

The two young men raced to Cherry's hotel. The story is that, as they were going up the elevator to the coach's room, Cherry was coming down another lift to check out. They missed each other completely.

Walker returned to Dallas and immediately enrolled at SMU. Layne returned to Texas. So the two buddies took separate roads and, instead of winding up in the same backfield, they became opponents. Within a week they were aligned on opposite sides of the field, launching one of the Southwest's most exciting and colorful personal rivalries.

Walker, who never had played a minute of college football, said afterward that he didn't know how he made such a quick transition. "Bobby and I got out of the service on Friday," he recalled. "On the following Monday," both of us were in uniform, practicing. The next Saturday we were playing against each other - I as a freshman, Bobby as a sophomore."

The first meeting of these two former teammates was dramatic. Walker ran 32 yards for a touchdown that put SMU ahead 7-0. Layne rallied Texas in the final period. Bobby passed to Dale Schwartzkopf for one touchdown and, after intercepting a Walker pass, threw to R. E. (Pappy) Blount for a 12-7 Texas victory.

Editor's note: Layne and Walker finally played in the same backfield for the Detroit Lions 1950-55, during which time the Lions played in the NFL Championship Game three times, winning two.

Frank Gifford on Vince Lombardi The Whole Ten Yards, by Frank Gifford & Harry Waters (1993)

Writers have carved careers out of making Vince Lombardi into something he never really was. The man I knew wasn't anything like that myth. In fact, he was one of the most down-to-earth human beings I've ever met. Maybe that's why I never called him "Coach" or "Mr. Lombardi" or, even in jest, "God." To me, and to most of us who really knew him, he was simply "Vince."

When Vince arrived in 1954 to take over our [New York Giants'] offense, we didn't like him at all. He was loud and arrogant, a total pain in the ass. We had a lot of nicknames for him, most of them unprintable. Vince had been a good high school coach at Saint Cecilia's and an outstanding backfield coach at Army, but he didn't understand pro football. He didn't have a clue. He immediately tried to install Red Blaik's offense from West Point, the old option T. The quarterback, moving down the line of scrimmage, either pitches the ball to the halfback or runs it. Now, our quarterback was Charley Conerly, whose days of running with the football were long gone - and he knew it. A lot of the things Vince wanted to do just wouldn't work in the pro game.

When Vince got up to the blackboard, he might have been teaching his fourth-grade math class at Saint Cecilia's. "This is the twenty-six power play," he'd announce. "The twenty-six power play, do you have that, Jack? The first step is for the right guard to pull back. He must pull back, must pull back, must pull back. He must pull back to avoid the center, who will be moving to the offside. So the first step is for the right guard to pull back. Got that, Jack? The first step is back."

We'd look at each other in disbelief. Here's a Charlie Concerly (whom Vince treated in the same way), having dodged bullets in the South Pacific and made All-America at Mississippi and lived through hell in the Polo Grounds, and he's hearing this guy tell him how to do it. You could see Vince was a terrific teacher, but these people had learned most of what he was teaching very early in their careers. They didn't require a lot of teaching. They required direction.

After our training-camp workouts, when many of the players gathered at a local beer joint, everybody began doing imitations of Lombardi. Some of them were quite hilarious. He just seemed a comical character to us, easy to parody. He had huge feet and big, long arms, and all those teeth. Someone once quipped that Vince had thirty-two teeth like the rest of us, but his were all on top. When we weren't laughing at him, our attitude was that we'd survive him. Somehow, this guy would be exposed and gotten rid of. As far as we were concerned, it was just a matter of time.

Then Vince did something both humble and smart. He began dropping by our training-camp dorm after meetings to talk to us about different aspects of the game to solicit our opinions of plays. At first that ticked us off. Charlie, Kyle [Rote], myself, and a few others were accustomed to coming back to our rooms at the 11:00 P.M. curfew, making the bed check and then sneaking out for a few beers. Now here was this bigmouthed rookie coach with a pasta name blocking our escape.

"How are things?" he'd ask, pulling out a chair from the desk.

"Uh, fine, Vince. Everything's fine."

"We're having trouble running the option play, aren't we, Charlie?"

Charlie, a man of few words if any, would pop his ankle and grunt something like 'Yep." There was an awkward silence. Finally, I volunteered what we were all thinking: "It's really not what Charlie likes to run. We really don't think it's going to be effective with Charlie."

"Well, what do you think about the fifty-four dive?" he replied. "How do you feel about the forty-nine sweep?"

Gradually, we felt comfortable enough to tell him. He'd just listen and nod. Then one night he suddenly said, "You know, if you don't mind, I could really use a little help from the older guys." Vince was a very intelligent man who sensed he was in trouble. So many coaches are so full of macho posturing that they'd have tried to tough it out. Vince knew better. What he was really telling us was, "Come on, I need your help."

That changed the whole tone of our relationship. All of a sudden, we found ourselves wanting to help him. We discovered that he was a real guy, a warm, funny guy. He was very Italian in the sense that he loved to laugh, loved his paste, and loved to have a few pops with his players. In later years, following practices, a bunch of us would drive over to his home in New Jersey, and his wife, Marie, would cook up a ton of spaghetti. We'd talk football and watch game films until Marie threw us out.

In terms of offensive strategy, Lombardi and the Giants learned from each other. Take the famous 49 sweep. When Vince installed it, he wanted the two guards who led the left halfback - yours truly - around the end to swing out several yards before they turned the corner. He wanted to be sure the penetration from our tight end blocking their linebacker didn't snarl everything up. Charlie and I disagreed. We felt the guards had to get to the corner as quickly as they could and turn it upfield. We knew that the defensive pursuit in pro football is too fast for that kind of maneuver. As big as Vince's ego was, he listened to us. We ended up running the 49 sweep half his way and half the way we thought it would work. The play turned out to be Lombardi's biggest ground gainer both in New York for me and in Green Bay for Paul Hornung. ...

Vince was famous for his tirades, but many, I felt, were calculated. Especially the ones at our screenings of the previous Sunday's game films. That's when he'd really hammer someone's performance. ... Only once did I witness Vince's theatrics backfire. We had a tough southern running back - I'll call him "Jones" - who, rumor had it, carried a knife around with him. He also performed best when no one got under his thin skin. During one film session, Vince seized on some frames that showed the guy failing to block a linebacker. "Look at yourself, Jones," he shouted, beginning his backandforth number with the projector. "Hear me, Jones? Jones? Jones? Jones?" After about a minute of this, from out of the darkness a very quiet, mean voice was heard: "Run that one more time, Coach, and I'll cut you." Vince gulped, swallowed deeply, and meekly hit the projector's forward button.

Put fifty men together for half a year, and you're going to see a lot of practical jokes. We loved playing them on Vince, just to watch him explode. Like the schoolteacher he once was, he liked to have his pieces of chalk laid out just so before he began a blackboard lesson. And like mischievous schoolboys, some of us would beat him to the meeting room to hide his chalk. Result: accusations, followed by expletives followed, more than once, by the crash of a hurled blackboard.

During practices, Vince hated anyone crowding him. He liked to stand exactly four yards behind whatever eleven guys were working on offense. The rest of us, who were not in the lineup, were supposed to stand at least three yards behind him. Naturally, we took that as a challenge. We were continually inching up to him, which invariably freaked him out. One day he threw down an orange peel to mark the line of demarcation. "Everyone stays behind the orange peel," he ordered. "Get in front of it, and you do a lap around the field."

We took that as an even bigger challenge. Each time he turned to watch a play, we'd push the peel closer to his rear end and creep closer ourselves. Finally, we were right on top of him.

When Vince looked back, he went ballistic. "I said, EVERYONE BEHIND THE BLEEPETY-BLEEP PEEL!" he screeched, his face turning a familiar purple. Then he glanced down and saw where the peel lay. It cracked him up. Of course, as soon as he stopped laughing, he moved it exactly three yards back.

See You in Detroit!

Starr: My Life in Football by Bart Starr with Murray Olderman (1987)

One of the most dominant teams in the history of professional football came very close to not even playing in a championship game. In 1962, there were no wild-card games ... Our team began the season knowing we had to win the Western Conference to earn the right to play the Eastern Conference champions for the title. ... Our biggest concern, therefore, was Detroit. The Lions had a talented and hungry team, having finished second to us in our conference in 1961.

After destroying our first nine opponents - six preseason, three regular season - we hosted the Lions in game four. Detroit was also undefeated, and the crowd was buzzing as the fans entered Lambeau Field on a cool autumn afternoon. In 1962, both teams exited Lambeau Field through the same tunnel, at the north end of the stadium. To make matters worse, or at least more uncomfortable, the opponents' locker room was separated from ours by nothing more than a ten-foot hallway. The doors on each end of the hallway were usually enough to prevent us from hearing the commotion next door, but not on that day.

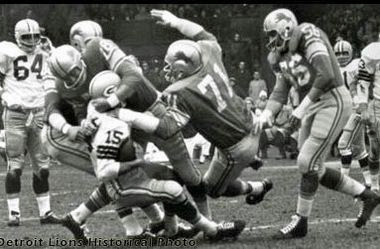

For the first time since Lombardi joined the Packers, his postgame comments were interrupted. It was Alex again. In the visitors' locker room, he tore off his helmet, threw it at Plum, and hit him squarely in the chest. Lions head coach George Wilson jumped between them to prevent pandemonium from breaking out, and said: "Look, guys, it's my fault. I made the call." As a matter of fact, Plum made the call, but Wilson tried to take the heat off him and get the players' minds off the game. "Hey, guys, shower up and let's get out of here." Wilson's thinking was sound, but the showers refused to cooperate. When the Detroit players filed into their shower facilities, they received another slap in the face when nothing more than cold water trickled out. A few minutes later, the Lions' equipment manager knocked on our door. "Dad" Braiser, our equipment manager, greeted him. "What do you want?" "I need to see Vince Lombardi." "What for?" "Our showers aren't working. We can't get much water and what does come out is ice cold." "Dad" told Lombardi about the problem and he decided to let the Lions use our showers. I was glad I had already finished, as I didn't need any more tension that day. For the next twenty or thirty minutes, our shower facility was silent except for the water streams from the shower heads. When the Lions dried off and walked back to their locker room, I expected them to be discouraged. They were outraged. As their last player exited, he headed toward the hallway, stopped, and said, "See you in Detroit."  Packers celebrate Hornung's winning FG vs Detroit. Did they ever.

The Lions had been hosting the Packers every Thanksgiving since 1952. With each succeeding year, the event grew in popularity and intensity. By 1962 it had become a national tradition for sports fans to turn on the tube and watch football on Thanksgiving. Vince Lombardi, however, detested the game. Lombardi was the most organized and disciplined coach I've ever seen. He loathed anything that would throw us off schedule, or disrupt our routine. In order to play on Thanksgiving Day, we had to fly to Detroit on Wednesday afternoon. And since we had to recuperate from Sunday's game by taking it easy on Monday, we had only this one day of intense practice before we had to play. So our concentration wasn't what it should have been on the day before the game. That would normally be enough to cause trouble by itself, but in 1962, it was compounded by the Lions' anger and desire for revenge. By the time the first half ended, Detroit led 23-0. It seemed much worse. I was sacked six or seven times, including once for a safety ... Lombardi didn't have to say much in the locker room. We had played listlessly, while the Lions performed as though they intended to give us a cold shower in front of the entire nation. The Lions continued to pour it on and were winning 26-0 at the end of the thid quarter. The rout was on and the Detroit fans loved it. Although the Lions were clearly the superior team that day, the character of our team surfaced in the fourth quarter, when we outscored Detroit 14-0, despite the fact that their defensive line was teeing off on every play. As we walked off the field, I knew we would destroy our next opponent. We defeated Los Angeles the following week 41-10.  Lions sack Bart Starr on Thanksgiving 1962. Postscript: Since the Lions had lost a second game, the Packers still won the Western championship with a 13-1 record.

Draftees or Prisoners?

The Other League: The Fabulous Story of the American Football League,

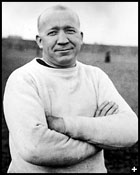

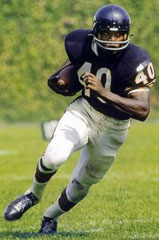

Jack Horrigan and Mike Rathet (1970) The AFL and NFL were duking it out for draft choices, raising player salaries across both leagues. The NFL might in the long run have worn down its rival, but on January 29, 1964, NBC announced a $36 million television pact with the AFL. The league's solvency was assured. The $100,000 draft choice contract would now be commonplace. Sonny Werblin [owner of the Jets] was the catalyst for a massive price escalation. When it came to signing a player, he put a price not only on playing talent but on any charismatic quality that might translate into money at the box office. It was such star quality he saw in Joe Namath. "When Joe walked into a room, you know he's there. When another rookie walks in, he's just another nice-looking kid. Namath's like Babe Ruth or Lou Gehrig.  Joe Namath signs with the Jets, bringing smiles to the faces of Coach Weeb Ewbank (left) and owner Sonny Werblin. Werblin decided early that he wanted to sign Namath. First, the Jets negotiated a trade with Houston, giving up the rights to Tulsa QB Jerry Rhome in exchange for a first-round draft choice. That choice was Namath. That was only the beginning. What followed was the biggest bidding contest in sports history up to that time, with the Jets and the St. Louis Cardinals matching offers. When Werblin got to $427,000, Namath was a Jet. By now Operation Hand Holding had turned virtually into body snatching, with the fringe benefits offered verging on the exotic. Notre Dame end Jack Snow was offered a honeymoon in Hawaii by the AFL Chargers, but Jack signed with the Rams. Pittsburgh LB Marty Schottenheimer accepted a deal with the Buffalo Bills because it included a rear window defroster for his new car. Such special attention turned off Gale Sayers. The Kansas HB said he signed with the NFL's Chicago Bears rather than Hunt's Chiefs when the Kansas City owner opened a door for him. "It made me uncomfortable," said Sayers, "having a millionaire holding doors for me."

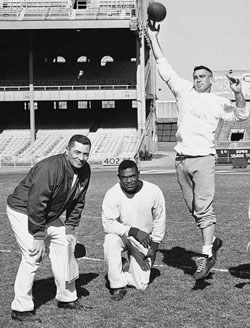

L-R: Jack Snow, Marty Schottenheimer, Harry Schuh Consider the case involving Memphis State T Harry Schuh. Schuh became the object of a manhunt when the Oakland Raiders whisked him away from Jackson MS where he played his final college game for Memphis State, to keep him out of the hands of the Los Angeles Rams.

His first stop was New Orleans, where the entourage cordoning Schuh off from the outside world stopped long enough to add his wife. Then it was on to Las Vegas, where Schuh's trail was picked up by the Rams. The Raiders reacted rapidly. Too rapidly for the slumbering Mrs. Schuh. Schuh was flown off by himself to Los Angeles, en route to a new hideout in Hawaii. Mrs. Schuh, awakening to find her husband gone, was told by the Raiders of the new itinerary. They suggested that she could best aid and abet the plot by flying to Los Angeles as a decoy, stopping there rather than continuing on to Hawaii. The Rams, trying a different tactic, flew east, reaching Schuh's parents at their New Jersey home and persuading them, in the interest of their son, to ask the police to issue a missing-person bulletin. But the Rams were too late. Schuh had signed and become a Raider. The NFL did the body snatching and the AFL did the chasing in the case of Prairie View receiver Otis Taylor. It all began with a telephone call Taylor received from the NFL's Cowboys inviting him to spend Thanksgiving in Dallas. He accepted, only to find he was a virtual prisoner, along with six other players. Led by the NFL's baby-sitters, the six spent a dizzying time changing motels four ties to confuse AFL pursuers. "We could see we were being kept away from the other league," Taylor said. "They didn't even want you talking to anyone in the lobby. Once they knew you'd talked to somebody they'd move you to another hotel." Meanwhile Lloyd Wells, a Kansas City scout, was trying desperately to track down Taylor. Wells finally learned of Taylor's whereabouts through friends and raced out to the motel, but was chased off by Taylor's guardians. Wells came back, slipped in behind the motel, jumped a fence and located Taylor's room. He tapped on the window, convinced Taylor to make an exit through it and sped him away in a car to take a flight to Kansas City. The Chiefs drafted him the next day and signed him immediately. Owners in both leagues were now beginning to question the wisdom of such strenuous - and expensive - battles. Might it make more sense to think about merging the AFL and NFL?

L: Gayle Sayers; R: Otis Taylor He Bought the Franchise for a Song - Literally The League: Inside the NFL, David Harris (1986),

Texas Schramm Jr. was born in 1920 in Los Angeles. He enrolled as a journalism student at the University of Texas shortly before the outbreak of World War II. There he played on the freshman football team and worked on the student newspaper. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Schramm joined the Army Air Corps and was discharged at war's end with the rank of captain. He finished his studies, then worked as a sports editor for two years before abandoning journalism for good. He got his first job in football in 1947 when he learned that the Rams managing owner, Dan Reeves, was looking for a new publicity director. As the Rams' general manager in the early 1950s, Schramm first met Pete Rozelle. It would prove a long association.

L: Tex Schramm; R: Pete Rozelle Tex Schramm stayed with the Rams for ten years until driven out by the disorder inside the franchise. When the opportunity to go to New York and join CBS Sports arose, he jumped at the chance and was eventually replaced by his friend Pete Rozelle. At CBS Schramm worked under Bill McPhail as assistant director of sports, obtaining events to televise. Among the contracts he handled were those with the network's assortment of NFL teams.

Tex Schramm's path finally merged with Rozelle's at the 1960 League meeting at which Rozelle was chosen commissioner. The other hot issue that winter was the prospect of expanding the League by two more franchises, one to be located in Dallas. Schramm was recommended to its prospective owner, Clint Murchison, by George Halas and Murchison hired Schramm as general manager of a franchise that did not yet exist. CBS let him resign contingent upon Murchison actually securing the franchise he sought. The primary roadblock to NFL expansion into Dallas in 1960 was George Preston Marshall, then owner of the Washington Redskins and one of the most powerful figures in the League. Marshall's television holdings were largely in stations around the South, and he thought of the entire area as Redskins home turf. He had steadfastly opposed any invasion of the region by another football team. In addition, there was no love lost between Marshall and the rich young Texan, Murchison. During the 1950s, Murchison had sought unsuccessfully to buy Marshall's franchise with the idea of selling it should the NFL expand into his hometown, but the deal fell apart because Marshall insisted on being kept on by the new ownership in a management position and Murchison did not want him. Marshall led the fight to keep the NFL from expanding into Dallas. Then Murchison played his hole card.

Marshall loved band music at football games and in particular loved his team's fight song, "Hail to the Redskins." He had, however, fired the song's composer, and in a fit of pique the bandleader had sold the rights to the tune to a Murchison crony. When Murchison threatened to deny the Redskins the use of their theme song, Marshall relented and the Dallas Cowboys were born on January 28, 1960. Not counting the price of the song, the franchise cost Murchison $600,000. As the new franchise's general manager, Tex Schramm immediately set about building his reputation as a "football man." Though starting an NFL team from scratch was no small task, the Cowboys would soon be identified by Rozelle as "the most successful modern expansion team in the NFL." At the fore in that rise was Schramm, "one of the game's great innovators." In 1962, for example, an IBM subsidiary approached the fledgling franchise seeking to sell it computers to handle its accounting problems. Instead, Schramm challenged them to develop a system to handle the task of choosing which football players to hire. Within a few years, the Cowboys' computerized system was acknowledge as the premier scouting apparatus in the League. ... Though long acknowledged as a "driving force" inside the League, Schramm confirmed his central role in 1966, when the war with the American Football League had been going on for six long and expensive years. Several different informal contacts between owners of the two leagues had gone nowhere. The contact that finally led to peace took place between Tex Schramm and Lamar Hunt at Dallas's Love Field airport on April 6, 1966. The two men knew each other from the early days in Dallas, when Hunt's AFL franchise was located there. At the time of their meeting, Hunt was headed to the AFL gathering in Houston, where Al Davis would be appointed AFL commissioner. Hunt and Schramm's first conversation about merger took place inside a parked car at the airport. "At this point," Schramm remembered, "we did not want to be seen together." Hunt was noncommital about the plan presented to him, but agreed with Schramm's proposal that that the two act as the leagues' intermediaries. A month later, the two met again at Hunt's home and then again the following week. At that point, Hunt was finally convinced that "any problems could be solved." That conclusion was followed by another month of frantic negotiations between Schramm, Rozelle, and the rest of the NFL owners on the one hand, and Hunt and the rest of the AFL on the other. All of it was cloaked in secrecy so intense that at one point, Schramm and Rozelle registered under assumed names in a Washington, D.C., hotel in order to meet with Hunt and then forgot to tell Hunt what name they had registered under. As a consequence, the AFL representative spent two hours in the lobby trying to locate them. On June 8, 1966, the agreement for merging the two leagues was announced. Its three key provision were the payment of $18 million in indemnities by the AFL, a four-year interim period before commencing business as a single organization, and the retention of Rozelle as the merged NFL's commissioner. In all accounts of the process, Tex Schramm was described as its "architect."  Schramm, Rozelle, and Hunt announce merger. Spurrier Delivers

Spurrier: How the Ball Coach Taught the South to Play Football, Ran Henry (2014)

Steve Spurrier saw greatness in a former fifth-string quarterback, looking through the tunnel to a field of dreams.

Shane Matthews, what do you want to run for your first play as starting quarterback at the University of Florida? Matthews thought a screen pass, or a draw play, might loosen up the team playing Oklahoma State in front of 75,428 Gators. "Shoot no, they aren't paying me all this money to come down here and run the ball," Spurrier said. "Heeeeeeeeeeeeeeere come the Gators!" the PA announcer bellowed. Running out of the tunnel, waving to his father and mother beaming in the first row in the end zone, with his wife, children, and Florida teammates weeping for joy, Spurrier led the Gators onto Florida Field on September 8, 1990, as Florida's head coach - running across real grass, hoping to lay to rest the old school motto, "Wait until next year." Scraps of that artificial turf Spurrier had ripped out and thrown to the curb got picked up and saved by disbelieving Gators, clinging to the past. He'd show them. Football is played on grass, under palm trees and tropical skies, with some guidelines he called "Gator Mentality." "Trips left, X Short, Blue Slide, Z Cross," he told Matthews, clapping his quarterback on the shoulder pads and sending him out for his first play, a 35-yard completion.  Steve Spurrier and Shane Matthews What should sportswriters call the passing attack Matthews triggered? He allowed that "Fun 'n' Gun" might lighten up the sports section his father carried around Green Cove Springs. That gave the Gators the mindset to go into Birmingham and withstand an early 10-0 Alabama lead, block a punt in the fourth quarter, and beat the Crimson Tide 17-13 at their stadium. Showing the disbelieving Gators back home Spurrier's team could play with the big boys. He'd met the enemy, and it was Florida. Former coach Galen Hall's $360.40 "loan" to a player needing to pay child support in 1986 made UF ineligible for the 1990 Sugar Bowl - and therefore unable to compete for the 1990 SEC Championship, the NCAA ruled the week after the win over 'Bama. Spurrier put on his go-to-meeting clothes and went to debate university officials over appealing that punishment. Looking the deciders in the eyes, he said no one on his team had done anything wrong. The doubts of Dr. Robert Lancillotti, dean of UF's business school, could no longer be contained. "We have never won the SEC! We're not going to win it this year! We've only won one conference game and we're talking about winning six more?" "Wait until next year," the administrators had to say to the football coach, giving Spurrier what he really needed: someone to prove wrong. Unfairness clouded his face when he huddled up his team and told them Florida would win that championship on the field - and he wouldn't let anyone forget who won it. Mississippi State and LSU got stomped at Florida Field, loud enough for the dean of the business school to hear. In the stadium boasting the SEC's loudest crowd, Spurrier sent Matthews onto the field with plays the Vols anticipated. They'd watched lots of film of Florida. When his tight end dropped a touchdown pass that would've tied the game at 7, cameras caught the velocity of Spurrier's visor hitting the ground. Big Orange rolled over Florida, 45-3 ... The major networks told their TV crews to keep a camera on the visor at all times. Disbelieving Gators resurfaced. Florida never could beat Auburn and Georgia back-to-back. Hearing that Auburn had lost its library in a fire, Spurrier sent his regrets: "Some of those books hadn't been colored in yet." No. 4 Auburn lost 48-7 to Spurrier. Florida still had to play Georgia the next week in Jacksonville. ... Fate favors men who want to win. The Ball Coach added that the game the Gators annually feared was played in Florida, in a stadium called the Gator Bowl. "We should beat them," he told his team. "We should beat them by a bunch." With cheers ringing through the stadium, Spurrier stood by the locker room door, waiting for his mom and dad to celebrate a 38-7 win over UGA athletic director Vince Dooley's Dawgs. Hearing about gatherings at cemeteries where cocktails were poured on the graves of Gators who'd lived and died without beating Auburn and Georgia back-to-back, Spurrier got ready to avenge the people who made them move out of a house they loved in Marietta, Georgia [when Bill Curry was hired as Georgia Tech coach and did not rehire Spurrier as O-coordinator]. His Gators clawed Bill Curry's Kentucky Wildcats, and stood alone atop the SEC at 9-1. Scoring 35 points and gaining 450 yards a game, rewriting their coach's passing records, Spurrier's Gators ripped away 57 years of SEC futility and 84 years of mediocrity - fielding the best team in Florida football history. A business school dean and a 45-30 loss to Bobby Bowden's Seminoles in Tallahassee couldn't deter the Ball Coach from painting "First in the SEC" on his stadium wall, to honor the 1990 team. ... Parcells Batting for Payton? From Parcells, A Football Life, Bill Parcells and Nunyo Demasio (2014) Sean Payton's heart was racing almost as rapidly as his mind on the morning of March 21, 2012. The Saints head coach remained in shock ... moments after learning the NFL's verdict for Bountygate. ... Because the surreptitious program, involving at least twenty-two defensive players, violated league policies and had occurred under Sean Payton's watch, the NFL had banned him for the entire 2012 season.

Having expected a suspension of only perhaps a handful of games, Payton reeled from the harshest penalty ever handed to a head coach in the league's ninety-two-year history. It included a loss of almost $6 million from his $7 million salary. At this unimaginable low point, Payton, who hadn't missed a football season since his Pop Warner days, could think of only one person to consult. Five minutes after getting the shattering news, he dialed Bill Parcells. Speaking via cell phone from his winter home in Jupiter [FL], Parcells calmed his former Cowboys lieutenant. During the brief conversation Parcells revisited an old lesson: collect as much information as possible before making any important decision. ...

Sean Payton and Bill Parcells with the Cowboys The penalties could only be appealed to Commissioner Roger Goodell ... by an April 12 deadline. Parcells advised Payton, who'd set the process in motion, to use the intevening time for contingency plans. Owner Tom Benson empowered his disgraced head coach to find a temporary replacement, and early the next morning, Payton dialed Parcells again, this time with an impassioned plea: fill in for him as head coach for the season. Payton emphasized his mentor's leadership qualities and his unique skill set as a former GM, head coach, and linebackers guru.

"Listen, you can help us out here. You can do all those jobs." Parcells replied, "I'll think about it." The 49ers hadn't been the only team in late 2011 to quietly try luring Parcells back to the sidelines. In November, Penn State contacted him after firing Joe Paterno ... Parcells responded to that inquiry by recommending Eric Mangini, whom he'd taken an increased role in mentoring since the young coach had become estranged from Bill Belichick. So Penn State interviewed Mangini before hiring Belichick's offensive coordinator, Bill O'Brien. After having shown zero interest in the Nittany Lions and briefly contemplating the 49ers job, Parcells strongly considered accepting New Orleans's short-term gig. Despite being only five months away from age seventy, Parcells wanted to help one of his favorite pupils, someone he considered to be like a son. Parcells's NFL staffs, including the one in Dallas, had given small cash incentives for statistics such as special-team tackles inside the 20-yard line, blocked kicks, and defensive turnovers. While those inducements technically violated league rules against salary-cap circumvention, the practice remained widespread - it was the NFL's version of jaywalking. ... Joining the Saints would mean only a six-month stint, and part of Payton's rationale on his replacement stemmed from intimately knowing Parcells's tendency to coach from year to year anyway. After Bill's Dolphins tenure, the Saints also provided an opportunity for him to burnish his legacy late by guiding an NFL-record fifth team to the posteason and, in a best-case scenario, punctuating his career with a third Lombardi Trophy. Conversely, Parcells faced a quandary: returning to the sidelines would reset the clock on his Hall of Fame eligibility. Five years after the 2012 season would put Parcells at age seventy-seven before his next crack. After being snubbed in February, however, Parcells refused to base his decision solely on the whims of Hall voters. On March 27, Sean Payton made his first public comments since receiving his suspension. While taking questions from reporters at the NFL owners meeting at Palm Beach, Florida, he caused a tizzy in the sports world by broaching the possibility of Parcells as a temporary replacement. Parcells's friends, his family, the media, and his former players inundated the retired coach with calls, texts, and e-mails to offer opinions or glean insight. ... Bill Parcells lived about twenty miles away from Palm Beach, so a few hours after Sean Payton's media Q&A the sullied coach took Saints executive vice president and GM Mickey Loomis to a nearby golf course to meet Parcells for the first time. The threesome played eighteen holes, giving Loomis and Parcells an opportunity to get acquainted. In discussing the New Orleans gig with Payton, Parcells became increasingly intrigued. The Saints were an offensive juggernaut, led by one of the best players of his generation. Parcells had reached three Super Bowls with different quarterbacks, but he'd never coached a signal caller of Drew Brees's caliber. The Pro Bowl quarterback had heard a great deal about Parcells from his head coach, and before New Orleans played in the 2010 Super Bowl, Payton introduced Parcells to Brees. The retired coach enjoyed getting acquainted with the Purdue product, and Parcells sensed that the feeling was mutual. Brees was Parcells's type of player, based on his football passion and ultracompetitiveness. ... He relished his first chance to coach an all-time great at quarterback ... Nevertheless, Parcells maintained reservations about the job. Sure, Bountygate had upended the franchise and created turmoil, a situation that he enjoyed addressing. But New Orleans needed a leader to keep things from cratering until Payton's return, not someone to jump-start the franchise, which is what Parcells loved most. Perhaps the most significant drawback involved Payton's staff. Parcells had no direct ties to anyone on it, a disadvantage compounded by the gig's brevity. Parcells said to himself, "So if things don't go well, people will say, 'This guy tried to change everything we were doing.' And if it does go well, people will says, 'Well, shit, he had a built-in advantage.'" Still, Payton emphasized the pluses. For one thing, New Orleans's off-season setup and practice structure were virtually identical to Parcells's system. After about a week of vacillation, with the media reading the tea leaves daily, Parcells remained open to the job. But he wanted to ease his nagging concern about overseeing an unfamiliar staff, one likely to view him as a lame duck. So Parcells asked the Saints for permission to hire two disciples with head-coaching experience. The organization obliged, and Parcells took steps to lure Al Groh, Georgia Tech's defensive coordinator, and Eric Mangini, an ESPN analyst two years removed from guiding the Cleveland Browns. While Tom Benson ... and Payton embraced the idea, Loomis seemed reluctant about it, perhaps sensitive to the effect on the incumbent coaching staff. Also, some reports speculated that Parcells would land an executive role in the organization after Payton's return. "Who knows what Loomis really thought? I don't have any idea," Parcells says. "I don't know Loomis; I only met him once. But guys like me threaten guys like him." In early April, the appeals process for Payton gave Parcells an extra week to weigh matters, and he focused on his reservations. Absent from the sidelines for six years, Parcells enjoyed retirement ... Parcells had a sweet deal with ESPN, too, working a few times each year on prime-time specials like Bill Parcells' Draft Confidential. Finally, Parcells remained uncertain about whether he possessed the energy required to do things in his maniacal way. ... So on April 11, Bill Parcells informed Sean Payton that he would be staying retired, but he offered to be of assistance in any other way possible. When news broke about Parcells's decision, his friends responded with a mixed reaction that encapsulated his own ambivalence. ... Bill Parcells felt at peace. "I'm at a different place in the world now."

Jerry's Not Happy "Jerry Football," by Don Van Natta Jr., ESPN the Magazine 9/15/2014 "I am still so damn mad," he snaps. "I get madder, every day, about missin' him." Him is Johnny Football.

At the NFL draft two weeks earlier, Johnny Manziel, the freshman Heisman Trophy winner and Instagram antihero, had fallen to the first round's 16th slot, owned by the Cowboys. Twitter nearly imploded. Among the organization's football minds, only Jerry Jones wanted Manziel. Stephen Jones, the Cowboys' executive VP in charge of player personnel, had lobbied hard against choosing Manziel. "I'm still so damn mad at Stephen," Jerry tells me, while Jones' younger son, Jerry Jr., says, "I'm the head of sales and marketing - where do you think I came down?"

But head coach Jason Garrett, his staff and the team's scouts had strongly advised against drafting Manziel. After all, Romo is entering the second season of a seven-year, $119.5 million contract, with $55 million guaranteed. But he's also 34 years old and coming off his second back surgery in less than a year. The inevitable quarterback controversy, not to mention the three-ring circus of Romo, Manziel and Jones in Big D, would have distracted everyone and could have provided enough TNT - and TMZ - to blow up the team. On draft night, fans and haters watched, enthralled, when Manziel fell in Jones' lap, their partnership looking preordained. In the draft room, Jones appeared anguished as he ground his No. 2 pencils in his right fist, the clock ticking. But Jerry Jones always gets what he wants, right?

L: Tony Romo and Jerry Jones; R: Stephen Jones No. Heeding everyone's advice, Jones selected Notre Dame offensive tackle Zack Martin, picking a player to protect Romo over a player who would have had Romo hearing footsteps. "I can't believe that Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus didn't buy the biggest elephant in the world," [former director of scouting for the Cowboys Larry] Lacewell says.

In his suite during the George Strait concert, Jones introduces me to Romo, who asks about the subject of this story. Jones answers for me, "Passin' on Manziel for Romo." The surprise draft decision reveals something not widely understood about his boss, Romo says: He selected a sound fundamental player needed to improve the offense, not the high-risk matinée idol of the draft. "More than anything," Romo says, "it just shows a lot of people that we're here to win - not just be a flashy program." Jones is beaming. He returns the sell: "And what is amazing," Jones says, "is if there's anybody on this planet that could've handled Manziel competin' with him ..." Jones drapes his left arm on Romo's right shoulder. "This guy could handle any damn thing - this is your fighter pilot. This is your fighter pilot. This is the guy you want goin' in, droppin' and winkin' at 'em, and comin' out and drinkin' beer. This is him. So he could handle it. It wasn't a question of not handlin' it." The analogy, such as it is, puts a smile on Romo's face. But during our initial conversation at the Ritz-Carlton several weeks earlier, Jones speaks longingly about Manziel's potential benefits to the Cowboys, long-term. "If we had picked Manziel, he's guarantee our relevance for 10 years," he says. "The only way to break out is to gamble - take a chance with that first pick, if you wanna dramatically improve your team," adds Jones, who likens himself to a riverboat gambler. "That's why I wanted Manziel, but I was the only guy who wanted him. I listened to everybody ... and I'm ... not ... happy." On the Radio City Music Hall stage, as Zack Martin donned a Cowboys baseball cap and hugged Roger Goodell, Jones seethed back in the draft room. "There's only one thing I wanta say," Jones whispered to Stephen. "I'd have never bought the Cowboys had I made the kinda decision that I just made right now."

|