|

The 1959 Ole Miss Rebels - 1

The 50 Best College Football Teams of All Time, Bill Connelly (2016)

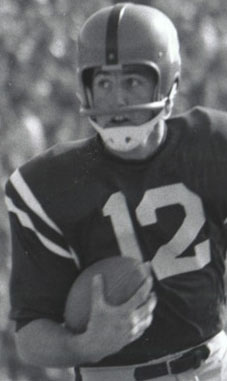

Ole Miss averaged 48y per punt against LSU that evening. It was almost unfair that Jake Gibbs was good at this, considering how good he was at everything else, too. He was the Rebels' quarterback and would become the SEC's player of the year in 1960. A stud baseball player, he also led Ole Miss to its first SEC title in 1959 and ended up playing parts of 10 seasons as a catcher for the New York Yankees. He hit 25 career home runs and was named to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1995. Now that's well-rounded.

Good punting was also unfair, seeing how incredible Ole Miss' defense was. It was always strong under head coach Johnny Vaught, but it was particularly dominant in 1959. The Rebels allowed only three touchdowns all year, and all three were either because of special teams or a turnover deep in their territory. Opponents didn't sustain a scoring drive of double-digit yardage all year.

The defense was so good that Vaught often didn't even wait until fourth down to punt. Granted, quick kicks were still rather common in the late 1950s, but with Ole Miss it was almost a sign of arrogance. "Sure, our offense is pretty good, but we'll go ahead and give the ball back to you. You know you can't do anything with it."

For most of the game Vaught was right. If Gibbs' kick with 10 minutes left in Baton Rouge had bounced out of bounds as intended, Ole Miss probably would have cruised to a 3-0 win in Baton Rouge in the biggest game of the season. With a win, the Rebels would have almost certainly become the SEC's third AP national champion in three years. It would have been the perfect culmination of what had become a 13-year building process for Vaught in Oxford.

Ole Miss had experienced scattered success before Vaught, but nothing like this. After going 17-3 in his first two years and winning both the SEC and the Delta Bowl in 1947, his Rebels had taken a brief step backwards, then surged forward again. Between 1952-63, Ole Miss would lose more than twice in just one season. The Rebs finished in the top 10 in 1952, 1954, 1955, and 1957, and finishing 9-2 and 11th in 1958 had been a source of disappointment.

From 1959-62, the Rebels would dominate college football in the South. But the 1959 squad was Vaught's best and one of the best in the sport's history. All the punt had to do was bounce out of bounds for Ole Miss to clinch immortality.

Unfortunately for the Rebels, it checked up. On a sloppy field on a muggy Halloween evening at Tiger Stadium, it bounced right up into Billy Cannon's hands.

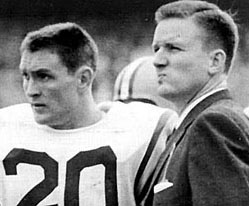

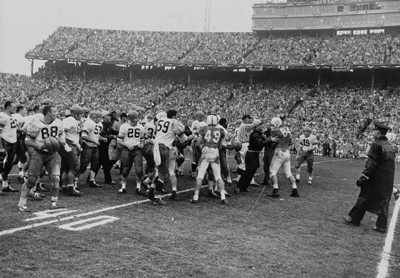

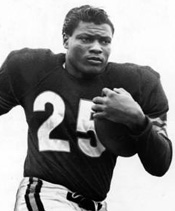

L-R: Johnny Vaught, Jake Gibbs, Billy Cannon and Paul Dietzel It rained about a third of an inch on Halloween 1959 in Baton Rouge. High of 80, average humidity of 97 percent. It was a throwback to weeks earlier, a sticky late-summer day in mid-autumn. The soupy vibe permeated even the black and white footage of the game.

This might have been the most anticipated game in either program's history. Former Army offensive line coach Paul Dietzel had taken the LSU job in 1955 at the age of only 30; what his resumé lacked in quantity, it made up for in quality. He had played for Sid Gillman at Miami (OH) in 1946-47, spent two years as Bear Bryant's line coach at Kentucky, and spent three years under Red Blaik in West Point.

It took Dietzel only four seasons to pull off what Vaught hadn't yet accomplished: a No. 1 ranking. Utilizing a deep squad, he used a three-platoon system - the White team (first-stringers), the Gold team (second-stringers), and the Chinese Bandits (a third string made of LSU's most energetic, physical reserves) - to soften opponents up and roll to an 11-0 record. The Tigers finished a perfect season with a 7-0 win over Clemson in the Sugar Bowl.

This didn't sit particularly well with Ole Miss or its fans. LSU had basically cut in line, and an already strong regional rivalry had grown nuclear. When Ole Miss came to town on Halloween, a packed house of 67,500 awaited. No. 1 vs No. 3: This was the toughest ticket in college football. Legend has it that someone traded his car for seats. An even more creative legend tells that someone offered his wife. LSU hadn't lost for nearly two full years, and Ole Miss hadn't lost for nearly one. The winner would become the de facto national title favorite. ...

Over the next 10 to 12 years, the college football universe would finally become fully integrated. In 1959, however, it was still a foreign, unrealistic concept in certain areas. Among other things, it made Ole Miss's scheduling anything but novel. The Rebels played Memphis 23 times in non-conference play from 1949-74, Houston 17 times between 1952-70, and Arkansas 10 straight years from 1952-61. They played series against teams like North Texas, Chattanooga, Trinity (Texas), Hardin-Simmons, and Tampa throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

Predictably, then, the 1959 season started against Houston ... A confusing new Houston offense had Ole Miss on its heels at the beginning of the game [but] the Rebels cruised 16-0.

The Rebel offense struggled a bit the next week in Lexington, too. But after a scoreless first half against Kentucky, Ole Miss drove 42y in six plays to take a 6-0 lead ...A field goal and a late touchdown gave Ole Miss a second-straight 16-0 win.

Ole Miss was all-defense so far. The offense would begin to play its part, at least until the trip to Baton Rouge.

Ole Miss and LSU had combined to allow just 13 points in 12 combined games. Defense that good doesn't only require down-to-down dominance; it also requires a little extra stiffening when the opponent gets a rare scoring opportunity.

Continue below ...

The 1959 Ole Miss Rebels - 2

Scoring chances were not particularly rare for Ole Miss in Baton Rouge, however, especially in a first half that took place mostly in LSU territory. Cannon fumbled at the LSU 21 early in the game, and Johnny Brewer recovered. After Charlie Flowers rumbled inside the 10 on third down, LSU stopped the Rebels on third-and-goal from the 3. A 22y Khayat field goal gave the Rebels a 3-0 lead.

When LSU lost two more fumbles (each recovered by Brewer), Ole Miss got more chances. Additionally, the Rebels saw drives end at the LSU 20, 22, and, in the dying seconds of the first half, 7.

At this point, Ole Miss had given up just seven points in 13 halves of football - there was reason to believe that a 3-0 lead would hold up over 30 more minutes. But after four brilliant offensive performances, these failures were particularly frustrating. Granted, LSU's defense was quite a bit better than Memphis' (Ole Miss won 43-0), Vanderbilt's (33-0), or Tulane's (53-7), but the Rebels had established a strong rhythm.

The offense may have unfortunately peaked a week too early. In a 28-0 romp over Frank Broyles' 10th-ranked Arkansas Razorbacks in Memphis, Ole Miss rushed for 201y and scored touchdowns on sustained drives of 80, 56, 49, and 20y. A little bit of that finishing power would have resulted in an easy win over LSU.

Sometimes a play's importance, its magnitude, makes it seem greater than in really was. Take Alan Ameche's run in the NFL Championship nearly a year earlier. That it ended the first sudden death overtime playoff game in NFL history, and that it was nationally televised on NBC, made it great. The run itself was a relatively simple, well-blocked run behind the right guard and tackle. Any long punt return, meanwhile, is going to be exciting and well-executed; it's probably going to feature at least one juke or broken tackle, too. We've seen a lot of them.

We haven't see this, though. Billy Cannon's return really is every bit as spectacular as its reputation. It would have stood on its own as one of the sport's greatest returns. That it happened in a game of such importance made it something still discussed with reverence nearly 60 years later.

Again, the punt was supposed to go out of bounds. Instead, it checks up near the "0" in Tiger Stadium's 10-yard line marker. Cannon fields it at the 11 and gets to the 16 before he has to make his first move. He jukes inside then jukes back toward the sideline, evading one shoestring tackle. As he crosses the 20, he skates past a pile-up of bodies with three tacklers closing in, and if he can somehow get through those tacklers, there's open space ahead. But he is stopped dead to rights at the 27 as a tackler gets a full hold of his left leg. He bucks free of the tackler at the 30, however, and somehow regains his balance well enough to juke another tackler at the 35.

And now it's off to the races. That he squirted through the coverage team surprises even the cameraman, who loses track of him for a moment, then catches up to him as he is shaking off one last tackler at the 47. Only the official on the sideline can take him down now. He races the final 53y in peace in the middle of a stadium that is now shaking at its foundation. The house is packed, likely well past fire code restrictions, and everyone in attendance has just witnessed one of the greatest individual plays in a team sport's history.

L: Billy Cannon starts his 89y punt return against Ole Miss; R: Cannon gets oxygen afterward. Cannon himself was gassed - he later told media that he stuck to the right sideline instead of crossing the field because he was fried. And that was before the three killer jukes and at least three broken tackles. He had already picked off a pass and had spent most of the game running into Ole Miss' defensive front, fighting to gain two yards instead of one. He was almost walking by the time he hit the end zone.

Worse yet fo Cannon: 10 minutes still remained. But suddenly all of Ole Miss' earlier missed opportunities were crystallized. If the Rebels had managed even another field goal earlier, they would have trailed by just a 7-6 margin. Instead, they would need a touchdown to win.

In response to this dagger of a return, Ole Miss mounted its best sustained drive of the evening. LSU's Chinese Bandits were on the field for the start of the drive as Cannon and the starters caught their respective breath. But as the Rebels penetrated LSU's 30, it was time for the White team again. Still, Ole Miss charged forward. Now, with time running short, the Rebels earned a first-and-goal from the 6. After a dive play gained one yard, Ole Miss QB Doug Elmore rolled out and gained three. The play had worked as well as any other for the Rebels that day, and they would call on it one more time.

On third-and-goal from the LSU 2, Hoss Anderson was stuffed for no gain. Down four, the Rebels had no choice but to go for the touchdown. With just 18 seconds left, Elmore rolled to his left and appeared to have a lane toward the end zone. But a diving lineman got a hand on his shoe, and as he lunged toward the end zone, he was met first by all-SEC guard Ed McCreedy, then by, who else, Cannon.

Everybody involved called it the greatest game they had ever seen or played, and while such superlatives are frequently thrown about in the short-term, the sentiment remains among those still alive to talk about it. To media after the game, Vaught said simply, "The only thing wrong with that game was that they got the seven and we got the three."

That Ole Miss was able to respond well down the stretch after such a gutting loss is a credit to the coaching staff, but the schedule maker helped. The week after this titanic battle, as undefeated Syracuse was fending off Penn State, LSU was falling victim to the upset bug. The Tigers fell to No. 13 Tennessee in Knoxville, 14-13. The Rebels, meanwhile, got a recovery game against Chattanooga (a 58-0 win) to catch their breath, then blew out the Volunteers, 37-7, in Memphis.

Syracuse's win, combined with LSU's loss, vaulted the Orangemen to No. 1 in the country. Continue below ...

The 1959 Ole Miss Rebels - 3

The bowl picture was beginning to take shape, and again, two different worlds (the segregated South and the rest of the country) were barely interacting. On November 14, the same day Syracuse destroyed Colgate, school officials accepted an invitation to play in the Cotton Bowl against the all-white champion of the Southwest Conference, be it Texas or Texas A&M. The Longhorns were No. 2 in the AP poll at the time of invitation, but any hopes of a No. 1 vs. No. 2 matchup died when Texas lost at home to No. 18 TCU. Still, they rebounded to dispose of A&M, 20-17, clinching a date with the Orangemen.

The Sugar Bowl, meanwhile, was staring at the possibility of pitting two SEC schools against each other, just as it had done in 1952 (Georgia Tech-Ole Miss). ...

Almost no school south of the Mason-Dixon line had yet integrated, but a lot of them were willing to play integrated schools. In fact, Georgia, which won the SEC when both LSU and Ole Miss fell, agreed to play an integrated Missouri squad in the Orange Bowl that very year ...

Schools in the deepest of the deep South - Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama - were not there yet. In fact, state law still forbade them from getting there. Seating at Tulane Stadium, home of the Sugar Bowl at that time, was designated for whites only; it said so right on the ticket. Racism was in no way limited to the South, but it was certainly more ingrained in ordinances. This made the sports teams at these schools sources of pride for those still clinging to the supposed glory of the Confederacy. They were unwitting fighters in the battle against change.

This also made finding Sugar Bowl pairings an increasingly difficult task. In some ways, in fact, the success of LSU and Ole Miss bailed the Sugar Bowl out. Without those schools to lean on, the bowl would have struggled even further. Aside from rare exceptions - Navy asserting pressure until the segregated seating was briefly lifted for the Navy-Ole Miss Sugar Bowl in 1955, for instance - the policy continued. From the 1956 season through 1963, eight Sugar Bowls featured 10 SEC appearances (five from Ole Miss, two each from LSU and Alabama), five SWC appearances (two from Arkansas), and one ACC bid (Clemson).

State pride or no state pride, frustration was building. Gibbs and Ole Miss won the 1959 SEC baseball title but had to refuse an NCAA tournament bid because of the possibility of playing an integrated team. Babe McCarthy's Mississippi State basketball team had to pass on tourney bids in 1959, 1961, and 1962 and watched Kentucky represent the league instead; in both 1959 and 1962, the Bulldogs were a tremendous 24-1, and in both 1961 and 1962, Kentucky went to the Elite Eight in MSU's place. While many players and fans probably shared their respective states' views on segregation, those who weren't completely committed to the idea grew irritated. They knew their sports legacies were being defined with an asterisk, and as Charlie Flowers said in a 2010 interview, "We just played who we were told to play."

Paul Dietzel's exhausted, banged up LSU Tigers weren't certain if they even wanted to play in a bowl to finish the 1959 season. They were weighing whether to pass altogether, accept a rematch with TCU in Houston's Bluebonnet Bowl (LSU had beaten the Horned Frogs, 10-0, in September), or elect for a rematch with Ole Miss in New Orleans. They were waiting to see if Syracuse beat UCLA - if the Orangemen won, then LSU would have no possible claim to a mythical national title with a bowl win, and they could pass on a bid. If Syracuse lost, and the national title situation was still blurry, they would accept.

The Sugar Bowl needed to know as soon as possible, however, and forced a team vote on November 23, two days after LSU's shaky 14-6 win over 3-6-1 Tulane. The Tigers elected to play Ole Miss again. They shouldn't have.

On November 28, Ole Miss romped over Mississippi State, 42-0. ...The Rebels outgained the Bulldogs, 422-115, and forced five turnovers.

On December 5, visiting Syracuse made a definitive statement, crushing UCLA, 36-8. ... UCLA had knocked off undefeated No. 4 USC in the Coliseum two weeks earlier. There would be no second upset.

The 1959 Ole Miss Rebels - 4

The 50 Best College Football Teams of All Time, Bill Connelly (2016)

Read Part 1 ... | Part 2 | Part 3 LSU wasn't fully invested in playing on January 1 in New Orleans, and it showed. Dietzel was frustrated enough by how his team was pressured into playing that he passed on a Sugar Bowl bid in favor of the Orange Bowl two years later.

Ole Miss, on the other hand, had plenty to prove, and did so.

LSU's run defense was still intact; Flowers rushed 19 times for only 60y. But Rebel backup QB Bobby Franklin completed 10 of 14 passes for 148y, and Flowers caught four passes for 64. Ole Miss led 7-0 at halftime thanks to a 43y pass from Gibbs to Cowboy Woodruff, and the Rebels scored touchdowns in each quarter of the second half as well. Cannon carried six times for 8y, and Ole Miss rolled, 21-0.

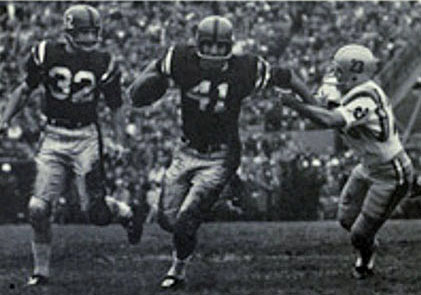

L: Charlie Flowers eludes Hart Bourque as Tommy Lott pursues. R: Larry Grantham clobbers Warren Rabb. The Cotton Bowl was a little bit closer and a lot more intense. Texas players allegedly spit on Schwartzwalder's black players and called them predictable names. Accounts differ, and the circumstances likely weren't as egregous as what was depicted in The Express, the 2008 Ernie Davis biopic. Still, fights broke out on multiple occasions, and according to a LIFE Magazine account, one Syracuse player said after the game, "We've never met a bunch like that before."

L: Ernie Davis; R: Fight at 1960 Cotton Bowl Whether Texas players were expressing their feelings or attempting to bait superior Syracuse players into losing their cool, it had little effect. The Orangemen were too strong for a solid but outmanned Longhorn squad. ... Syracuse won 23-14.

The majestic Orangemen had dominated virtually the entire season ..., and they capped the run with a thorough win over the No. 4 team in the country. That they couldn't play the No. 2 or No. 3 team in a bowl hardly seemed like it mattered at that point. They had made their case. ...

In the fall of 1962, a black student named James Meredith enrolled at the University of Mississippi. As the federal government attempted to enforce his right to enroll in the face of state resistance, members of the football team, unbeaten and soon to claim a share of the mythical national title, were asked to help quell an Oxford riot.

In the spring of 1963, the Mississippi State basketball team, tired of passing on opportunities to prove itself and buoyed by a fan base with the same sentiment, sneaked out of Starkville on a plane to Nashville, then flew to East Lansing to face Loyola (Illinois) in the NCAA tournament.

In the fall of 1964, with segregated seating off the books, Tulane Stadium welcomed a Sugar Bowl battle between LSU and, as fate would have it, Syracuse. Thirteen days earlier, in the Bluebonnet Bowl in Houston, Tulsa beat Ole Miss, 14-7. Tulsa's Willie Townes, an African-American end from Hattiesburg, Miss., ... was named the game's most outstanding lineman.

The world evolves more slowly than most would like. Sometimes, sports can help to, every so slightly, speed the process along.

"I Feel Like Hanging It Up."

More Than Just a Game: My Life On And Off the Sidelines

Preface by Bill Smith

Coach Bobby Bowden with Bill Smith (1994) What is Florida State football coach Bobby Bowden, the man who is fast becoming a legend in the South, really like? Well, the best way to describe the man from Birmingham is to tell stories about him. Bowden would like that because he's a storyteller himself.

One came to mind when trying to figure out a way to begin this book. It was October 2, 1973, and Bowden, then the 43-year-old head coach of the West Virginia University Mountaineers, had his team on the road. He and his Mountaineers were in the heart of Pennsylvania, in the blustery Nittany Valley, a place where West Virginia teams had stumbled time after time, year after year.

No Mountaineer team had won at Penn State since 1954.

Bowden had different ideas this time around. A year earlier his Mountaineers had finished 8-3 in the regular season and earned a spot in the Peach Bowl (where they suffered a 49-13 loss to North Carolina State). But one of those three regular season defeats came on West Virginia's home turf at the hands of Penn State 28-19. And the play that propelled the Nittany Lions to victory came when West Virginia blocked a field goal attempt and the Lions turned it into a fluke touchdown.

And the last time Bowden's team had visited State College PA, it had suffered a 42-8 defeat. The coach was determined that would not happen again.

Bowden's team wasn't all that talented. It went into the game with only a 3-3 record. But those wins had been over Maryland (20-13), Virginia Tech (24-10), and Illinois (17-10). Bowden figured, "We can't be all that dad-gum bad. If we play like we did in our victories, we just might be able to stay with Penn State. Those boys put their pants on the same way we do."

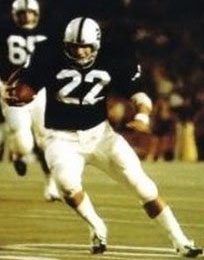

Penn State had an outstanding running back named John Cappelletti, who would go on to win the Heisman Trophy. Bowden knew Cappelletti was a threat, but he figured to counter with a threat of his own, in speedy wide receiver Danny Buggs, who was averaging 23 yards per catch and 14.2 yards on punt returns.

L-R: Bobby Bowden, John Cappelletti, Danny Buggs Unfortunately for Bowden, his team suffered an embarrassing 62-14 defeat that afternoon. It remains the worst defeat in his illustrious coaching career, one that now spans five decades and has seen him become the fifth winningest coach in the history of the game. In that '73 walloping, Buggs caught a school record 96-yard touchdown pass. But Cappelletti scored and scored - four times in all.

Long after the game, and long after all the West Virginia players had left the visitors' locker room, a local sportswriter - me - found Bowden sitting on a bench in a corner of the room with his head down. He had showered but hadn't dressed. He had a towel draped over his lap. He was obviously depressed.

I said, "Don't worry, Coach, it's not the end of the world. Your team will bounce back." Being his long-time friend, I tried to be cute next by adding, "They only beat you by 48 points. It's just a loss. You'll beat the Hurricanes next week in the Orange Bowl." Bowden looked up, shook his head, and said, "Naw, I'm just not getting the job done. I feel like hanging it up."

I said, "What are you saying? Give up coaching? That's the dumbest thing I ever heard you say. Your coaching can't just be measured in terms of wins and losses. You're a great influence on a lot of young men's lives. That has to stand for something."

"I'm not even sure I'm doing a good job of that," he muttered. "I'm so sick I want to die."

"Now don't do that, Coach," I rejoined, not really knowing what else to say. And Bowden made an effort at a smile and drawled, "Well, I ain't gonna die, but I'm so sick I could throw up." His team did bounce back the next week, with a 20-14 win at Miami.

But while that conversation was taking place in the Beaver Stadium visitors' dressing room, there was another scene taking place. It was in the home team's locker room. This was one of jubilation. Cappelletti was hugging a young boy, his little brother Joey. Joey, his face wan and body frail, was dying of leukemia. Everyone in the room knew it.

Prior to the game Cappelletti wanted to do something to make Joey happy, to ease his suffering for one brief afternoon. So he asked him, "Hey, Joey, how many do you want me to get today?"

Joey answered, "Four. Score four touchdowns."

"That's a tall order, but OK, you got 'em," said his big brother. Youngsters sometimes ask seemingly impossible things like that of their heroes. But big brother went out that day and got Joey those four touchdowns, and there was happiness in the Penn State locker room - for Joey. Years later, Bowden heard about what had happened in the Penn State locker room when a movie, Something for Joey, was made of what Cappelletti did for his dying brother. Bowden smiled that smile of his and said, "Lawh, if I had known that ... well, I just might have wished Cappeletti had scored a couple more. That game meant a lot to me at the time, but I know it means a whole lot more to John Cappelletti and his little brother. It was more than just a dad-gum game to them."

The First One

'Cane Mutiny: How the Miami Hurricanes Overturned the Football Establishment,

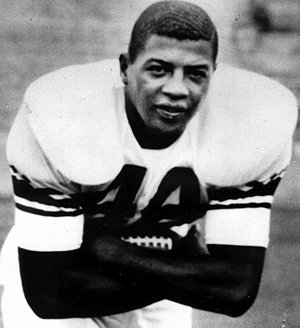

Bruce Feldman (2004) "Dear Nigger," the letter began. "Do you know what Hell is? We will make your next 4 years at Miami hell." The envelope was postmarked February 2, 1967, and it was sent by a group calling itself Patriotism, Inc. Ray Bellamy had been getting letters like this for two months. They all started out the same: "Dear Nigger ..." They all challenged his sanity, telling him to remember his place. If he didn't, ... they'd get him. The letters always came to his school, Lincoln Memorial High in Palmetto FL. Bellamy was the president of the student body at all-black Lincoln, an honor student and a star wide receiver for the football team. ...

Bellamy was six-foot-five, 190 pounds, and could run the forty-yard dash in under 4.5. And he played on a powerhouse team that once beat a team from Clearwater 89-0 - ... In Bellamy's three seasons at Lincoln, the team was 25-0. ...

The next step for a player of Bellamy's gifts would be college. That meant Florida A&M or Bethune-Cookman College or maybe mighty Grambling in Louisiana.

What about Florida's Big Three, Miami, Florida State, and Florida? Not in that day. Colleges in the South were petrified about even recruiting a black player. (Wake Forest had three in the mid-sixties but still wouldn't acknowledge their existence four decades later.) ... However, the University of Miami ... set out to change that.

The green light was given by Miami president Dr. Henry King Stanford, a country-as-corn-bread Southerner from Americus GA who wanted the school to be seen as a leader. College football, like the rest of society, was divided into two halves: the South and the rest of the country. Other programs in the North and Midwest began recruiting black players from the segregated South in the early fifties. In 1953, J. C. Caroline, a black sophomore running back from Columbia SC became a consensus all-American for Illinois, leading the country in rushing with 1,256 yards in a nine-game schedule. Illinois fans loved Caroline's dazzling style. So did rival Big Ten coaches. Within the next two years, a new wave of black football talent migrated to Big Ten country. ... Michigan State built a powerhouse, winning six national titles in the fifties and sixties with the barred black stars from the South as its foundation. ...

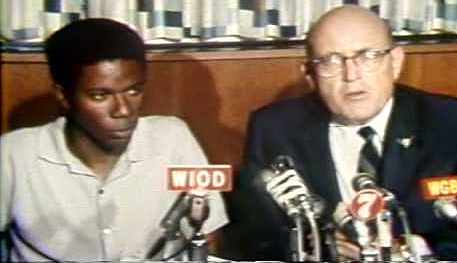

Ray Bellamy and Dr. Henry Stanford, J. C. Caroline Miami, Dr. Stanford believed, was the ideal proving ground [for recruiting black players] because, yes, it was Southern, but it really wasn't the South. The 'Canes ... had many players who were Southerners, but also had many who were from the Northeast and Midwest ... Stanford had informed his head coach, Charlie Tate, that the time was right, and soon the search was on for the right student to cross the color line. ... Colleges relied on the part-time help of well-placed alums, who would moonlight as recruiters and get paid in game tickets. Guys like Ed Dick.

An insurance agent, Dick covered Jacksonville and the Tampa area for Miami. Over a 15-year period starting in 1961, Dick sent 15 players to Miami. Dick was a Miami grad, he sat on the local school board, and he was a staunch civil rights advocate. He hired the first black insurance agent in the state of Florida. "I got called 'N-lover' more times than anyone in the history of Manatee County," Dick says. He started pushing UM to recruit black players in 1961. That was the same year Miami's board of trustees voted to allow blacks into the school. But suiting up a black football player proved to be a struggle ... "They kept saying no, they couldn't," Dick said. "There was always an excuse, though. They kept saying how they were afraid of schools canceling games against them because they wouldn't play a team with a black player."

That argument didn't wash, though. Even Alabama was playing teams with black players. That started in 1959, when the Crimson Tide accepted a bid to play an integrated team from Penn State in the Liberty Bowl and attitudes began to soften. Not that the school loved it. Sure, death threats were made on the lives of Bryant and the Alabama university president, but the '59 Liberty Bowl was played without incident. Throughout the 1960s, Bryant continued to accept bowl bids to face integrated teams. Before each of these bowl games, Bryant would give his players, many of whom had never played against a black player in either high school or college, the same speech: "Treat 'em like any other player. Knock 'em on their ass and then help 'em up."

In the summer of 1966, Dick ... knew exactly where to start looking: the little school right across the river, Lincoln High School. "We were looking for a special kind of person," says Dick. "Like a Jackie Robinson type of person."

Eddie Shannon, Lincoln's head football coach, introduced Dick to Ray Bellamy, the school's star receiver. ... "Ray had the hands, the speed, but he had the character too," Shannon said. "I didn't worry about him academically, and I knew he was humble enough that he could handle adversity." ... The coach said he was always impressed by the way Bellamy never seemed to let anything slow him down. ... Shannon sat down with Bellamy to see if he was interested in being "the first one," the one who would break football's color barrier in the South. Bellamy was. But first, Shannon had to make sure that Bellamy understood what he was getting himself into. "Do you think you can take people throwing stuff at you?" he asked. Bellamy nodded. "Do you think you can take people spitting at you?" Again, Bellamy nodded. "Well, then," the old coach continued, "if you think you can take a little bit of hell, then you can go on and get that education."

Dick's first meeting with Bellamy came after watching a Lincoln practice. Dick's immediate reaction? Wow! "He was bright, he was charismatic, he had a lot of leadership qualities," Dick said. "He was just very impressive. Right from then, I knew, Ray Bellamy was the fit. He was exactly what we wanted." ...

On December 12, 1966 ... Ray Bellamy made history. He signed to play football at the University of Miami. ...

Once word got out about his decision to play for Miami, the hate mail started to show up at Lincoln. He'd get it every week, telling him how they would kill him, kill his family. Bellamy vowed he wouldn't let "those people" stop him. "I'm fearless," he said. "Even when they threatened to kill me, I wasn't scared. My mom was more concerned with her baby being hurt than I was."

By the time Bellamy arrived on campus, the university had already admitted 12 black students. Before the first week had passed, Bellamy knew the name of each one. ... Of course, that didn't mean Bellamy's transition into Miami was seamless. "When I first got there, no one knew how to act around me," he said. "I paralyzed people. They just didn't know how to deal with me." Some, though, were quite certain how they wanted to treat Bellamy. One night he came home from practice and found a hate letter tacked to the door of his dorm. The next night he got another one. A week after that he had to dive out of the way after someone tried to run him down with a car. ...

He says when the school felt things were serious enough, they did "some things" to protect him. Like before UM faced Auburn in 1968, the school notified the FBI about a death threat against Bellamy. ...

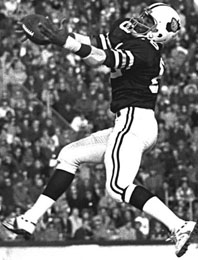

It didn't hurt his cause that his teammates knew right away that the kid was legit. "Ray truly was a great athlete," said Ted Hendricks, who played DE from 1966-68. "His teammates had to respect that." Bellamy could outrun all the defensive backs, he could make these never-seen-before one-handed snatch catches, and they couldn't tackle him. More important, he could help them win. ... [After playing on the freshman team] he led Miami in receptions with 37, the most ever by a Hurricane sophomore. Bellamy followed up that with a great junior year and looked primed for an NFL career.

But on January 3, 1970, while driving back to school from his home in Bradenton with his girlfriend, Bellamy fell asleep at the wheel a few miles from Miami. His blue Chevy Nova went off the road and smashed into some pine trees. Bellamy's girlfriend emerged virtually unscathed, but he broke his arm and his leg and suffered a head injury. He was hospitalized for four months and missed his senior season.

Bellamy, though, was convinced he would leave his mark on UM. He ran for student body president in 1971, and - imagine that - he won. ... Before Bellamy left UM, Miami had 14 black players on its team.

"Have you ever seen anything like that in your life?"

Don Shula: A Biography of the Winningest Coach in NFL History, Carlo DeVito (2018)

The 1983 NFL Draft was arguably the richest singular draft in the history of the NFL. Everyone knew it would be special, but it would take the league a generation to see how much so. ...

Quarterback John Elway of Stanford was the big prize. Other candidates were fellow signal-callers Jim Kelly, Tony Eason, Todd Blackledge, and Dan Marino. Marino had been the absolute undoubtable star of the 1981 season, his junior year at Pitt, but his senior year was a flop in 1982, and his stock had fallen.

The problem was simple for the Dolphins. Who would be available with the 27th pick? They had gone to the Super Bowl and lost, and now they would get to pick second-to-last in the draft. Shula felt for sure no quality quarterback would be left at the end of the first round. As the draft drew near, he focused on Mike Charles, a defensive lineman from Syracuse.

The story how Marino fell so badly is still legendary. In 1982 and 1983, there had been rumors that he was using drugs. Were they true?

"It was certainly out there that there were 'issues' with Marino," said Ray Didinger of the Philadelphia Daily News. Chuck Noll, a decade after the draft, admitted the Steelers had passed on Marino because of those rumors. "It started off with just the idea that he was partying. Then it grew more sinister from that," Didinger recalled.

"I never took any tests," Marino said later. "One time somebody wrote that, but that's something I can't control. If I worried about everything that was written about me, I wouldn't have a good time."

Foge Fazio, Marino's head coach his senior season, later admitted to the press that he felt vindictive gamblers started the rumors. "A lot of it was disappointment we didn't beat the point spread," Fazio said. "That's where the viciousness came out."

As expected, Elway went No. 1. ... Todd Blackledge of Penn State was the next quarterback picked at the No. 6 spot by the Kansas City Chiefs. Jim Kelly of Miami went to the Buffalo Bills at No. 14, and Tony Eason of Illinois went next at No. 15 to the New England Patriots.

"It's a weird day, really," Marino remembered. "You're sitting there ... I know it's football, you're going to play in the NFL, but every other kid that graduates college and has a chance to get a job, they kind of know where they're going or what their profession is going to be or what they're going to do, and you can sit there and not know if you're going to be in Seattle or Miami or Arizona. That part is tough, I think." Added Marino later, "I just remember it being a long day."

"People started finding reasons to not like Marino, and I think that the drug rumors were just another thing that they threw on the pile," agent Marvin Demoff said.

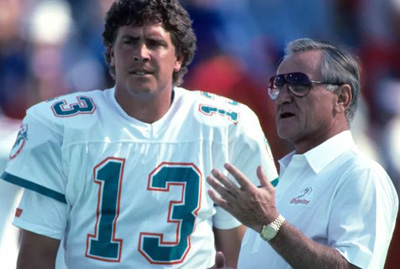

L-R: Dan Marino, Don Shula, Foge Fazio To be fair, the entire media had started to play Marino down. Gordon Forbes of USA Today wrote of Marino, "Stands tall in the pocket and has a good view of the field. Sets up quickly and gets good, deep pass drops but lacks a classic delivery. Scouts say he often forces the ball into a crowd and is frequently intercepted." In the Miami Herald, Larry Dorman wrote, "After Marino's inexplicably poor senior season, he's lucky to still be considered a first-rounder. Still, as a prospect, he's worth taking a chance on."

Also in the Miami Herald, Edwin Pope wrote, "The word from Marino's hometown is that the Panthers' all-time passing leader declined last year as a twin result of a) inflated ego, and b) pressing to impress the pros after he finished fourth in Heisman Trophy voting as a junior. He developed the idea that he was God's gift to football. Dan was a down-home Pittsburgher who started thinking he was Joe Namath. It hurt the team, along with some other things, like losing some top receivers and also that head-coaching switch-over from Jackie Sherrill to Foge Fazio."

"This happens in a lot of drafts," Didinger said. "Once a guy starts falling, everybody runs the other way. Everyone assumes everyone else knows something, and they back away."

"People were scared that they couldn't handle him," said one NFL scout later. "Why waste a No. 1 on a problem?"

At No. 24 in the first round, the Jets were on the clock. Days before, Fazio, a good friend of Jets head coach Joe Walton, who had just replaced Walt Michaels, called to vouch for Marino. As the tension mounted, Jets fans in the balcony of the New York Sheraton hotel, where the draft was conducted, could be heard chanting loudly, "Dan Marino! Dan Marino!" Commissioner Pete Rozelle announced, "With the 24th pick, the New York Jets select quarterback ..."

There was a pause. "I don't think Rozelle did it on purpose. But for dramatic effect, he couldn't have done it better," remembered Didinger. "Ken O'Brien, University of California-Davis," Rozelle finished.

"The cheers turned to screams of anguish - and then boos, in just a second," Didinger said.

The Bengals and Raiders also passed on Marino, and then came the Dolphins at 27. (Miami D-coordinator) Bill Arnsparger pushed Shula hard to take Charles. "The pressure was on me to take the defensive lineman," Shula recalled. Future Hall of Fame defensive back Darrell Green was also on their list of available players.

"Everybody's trying to figure out now why he was drafted so late," said Shula. The Dolphins head coach was thrilled to find Marino available. "We had a strong commitment to Marino that others did not. We heard rumors, different kinds of rumors. We checked them out and did not hear anything that changed our minds. I called Foge Fazio, and he gave me his strongest recommendation. We knew all we needed to know." ...

With our situation and our evaluation of Dan Marino, we felt he was a good pick," said Shula. "Certainly good credentials. Didn't have the best senior year, but when you look at him and evaluate him throughout his career, you have to be pretty impressed."

"What Shula saw was a franchise player who could carry a team for a decade or more. He saw an already polished drop-back passer who had spent four college seasons in a pass-oriented offense. He saw the MVP of both the Senior Bowl and Hula Bowl who had thrown for 8,416 yards and 79 touchdowns at Pitt," wrote Paul Attner in the Washington Post.

"I was happy the Dolphins got me," said Marino. "This is all I've wanted to do, to get a chance to play in the pros, and Miami is giving me this chance. Everything else is behind me, and I let it go at that."

"You probably got the best guy in the draft," said Chuck Noll to Shula by phone after the Dolphins picked Marino.

There was a story that was oft repeated in Miami sports circles in the subsequent years. Shula was quiet as he watched Marino work out for the first time that spring of 1983. Shula was sure he'd gotten a "steal" in the draft, though how much of a steal he wasn't sure.

"Shula stood behind Marino, watching him effortlessly flick pass after pass, using not much more than his wrist. He looked like a man fly-casting with a fishing rod, but the ball would zing downfield 40 to 50 yards. Then Shula did something he almost never does. He walked to the sideline to chat with a friend, Edwin Pope, sports editor of the Miami News," remembered sportswriter Larry Felser.

"Have you ever seen anything like that in your life?" Shula asked Pope quietly.

Brees Ends Up in New Orleans - 1

Special Retirement Tribute: Brees, Bauer Media Group (2021)

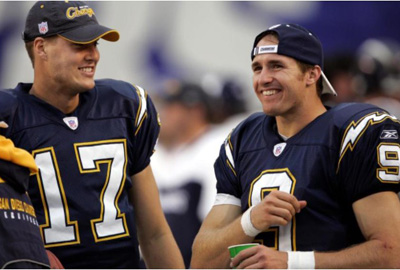

When the 2004 season ended, Drew Brees was due to become a free agent. He was coming off the best year of his career, and there would be many suitors. There was uncertainty whether - with Philip Rivers in the fold - Brees would remain in San Diego. However, on Feb. 17, 2005, despite having drafted Rivers the previous year, the Chargers designated Brees their franchise player. Other teams could still make Brees offers, but if they signed him, they would owe San Diego two first-round draft picks. It was a win-win situation for the Chargers. The team had a lot of talent, and Brees' $8 million, one-year contract gave San Diego added security. Though Brees' record as the starter was 21-22, including the playoffs, he wasn't worried about his own job security. The franchise tag solidified Brees' belief in his ability.

As far as Brees was concerned, he served as his own competition. "I'm always competing against myself," he said, "and every day I approach it is, 'How can I make myself better?' Not, 'How can I just beat out that guy next to me.' I'm not worried about who is there because in my mind, I'm the starting quarterback. It's my team and that is the way it is."

The confidence that ingratiated Brees to the franchise in the beginning would be needed in abundance. The Chargers failed to start the season up to their preseason hype, losing their first two games with Brees throwing three interceptions and only two touchdowns. San Diego rebounded to win nine of its next 12 games. Sitting at 9-5, the team remained in playoff contention heading into a key Week 16 matchup against the 8-6 Chiefs. But Brees threw for just 161y, and San Diego's 20-7 loss to Kansas City eliminated the team from the playoffs.

Philip Rivers and Drew Brees The following week, with the Chargers backed up to their own 9y line with 3:37 left to play in the second quarter of a meaningless season finale at home against the Denver Broncos, Brees dropped back into his own end zone. As he released the ball, Denver S John Lynch hit Brees from the left side. The ball bounded out of the quarterback's hand toward the 1y line, where Brees tried to recover it. As he did, Broncos DT Gerard Warren slammed the quarterback into the ground. Brees immediately knew something was seriously wrong. As he left the field, he couldn't left his arm above his shoulder. The entire right side of his body was numb. Adding insult to injury, the home crowd cheered loudly when Rivers came onto the field for the next series.

Three days later, Brees flew to Birmingham, Ala., to visit the clinic of renowned orthopedic surgeon Dr. James Andrews, who diagnosed the injury as being worse than what had been reported. Brees suffered a 360-degree torn labrum and a 50 percent tear of his rotator cuff. When Warren hit him, Brees' arm bone went out the bottom of the socket, which was a rare occurrence. The quarterback's career appeared to be in jeopardy.

Brees and Dr. Andrews discussed the pending surgery. If the procedure could be completed without cutting the labrum, recovery time would be reduced significantly. If the doctor did have to cut, however, Brees would not recover prior to the start of free agency. Dr. Andrews led a team of four doctors during a four-hour surgery that had to be finished in the requisite time. Otherwise, Brees' shoulder would have swelled up to the point where the surgery could not be properly completed.

Once Brees came to, his first words to a nurse were: "Did he have to cut?" From the nurse's answer, Brees thought that they had cut. But Dr. Andrews entered the room and said he had not. Eleven anchors were put in the labrum and two more in the rotator cuff. "If I did that surgery 100 times, I couldn't do it as well as I just did," Brees recalled Dr. Andrews telling him. "I did my job. Now it's on you."

Crediting his strong Christian faith, Brees learned a signifance lesson during his injury and rehabilitation: "If God leads you to it, he will lead you through it," Brees wrote in his 2010 book Coming Back Stronger. "If you let adversity do it work in you, it will make you stronger."

"He's probably 1-in-100 who would come back from that injury," Dr. Andrews told ESPN four years later. "But he was the right one, and I believed in him from the word so."

Continue below ...

Brees Ends Up in New Orleans - 2

Special Retirement Tribute: Brees, Bauer Media Group (2021)

Read Part 1 That March (2006), Brees explored free agency. San Diego offered an incentive-laden contract for five years and $50 million. It was considered by many to be a lowball offer. Brees had never ben heard of new Saints coach Sean Payton until he got a call from him in March 2006. The Saints set up a meeting.

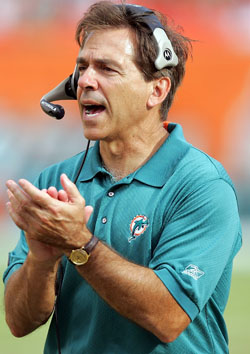

The only other team seriously interested in Brees - the Miami Dolphins - found out about the meeting and wanted to set up their own meeting before Brees met with the Saints. Nick Saban and Dolphins general manager Randy Mueller flew into Birmingham, where Brees was still rehabbing his shoulder. They met Drew and his wife, Brittany, at a pancake house. The couple liked Saban, and they agreed to set up an official meeting with the Dolphins soon after Brees met with the Saints – that meeting had already been arranged. Drew noted that Saban was really trying to impress Brittany. "We have great communities and great places to raise a family," Saban said.

Later that same day, Payton and Saints general manager Mickey Loomis flew to Birmingham. Then, they all flew together to New Orleans, where the Saints rolled out the red carpet for their target. The city was still recovering from Hurricane Katrina, and the local economy needed a jolt. Brees was just what the team and the city needed. The Saints offered a six-year contract for $60 million, including an $8 million guaranteed signing bonus. But there was still the meeting in Miami, which had the sun and the surf and the draw of South Beach.

Dr. James Andrews, Drew and Brittany Brees Brees' agent Tom Condon helped weigh the two teams. "Drew, the overall reputaton of the [Saints] organization is not good. The team has been pretty dysfunctional for a long time." Condon thought Loomis would have a hard time attracting additional talent to New Orleans. As for Miami, Condon told Brees: "There's an unbelievable tradition with the Dolphins. They've won Super Bowls." The Saints, meanwhile, were the Aints.

Brees was excited by the prospect of playing in Miami, but the Dolphins' medical staff interceded. They subjected him to what he thought was an unusually long six-hour medical examination, making sure his shoulder was worth the amount of money it would take to sign him. It's unclear whether the Dolphins actually made Dolphins an offer. But after team doctors told Mueller, the general manager, they didn't think Brees' shoulder would hold up, the Dolphins traded a second-round pick for former Minnesota Vikings QB Daunte Culpepper, who'd had a knee injury treated by Dr. Andrews a few months earlier.

L-R: Nick Saban, Daunte Culpepper On March 14, 2006, Brees signed with the Aints, determined to rid the town of that reputation. He was drawn by the city's "clear sense of home." Six years later, Saban, who ultimately had had the Dolphins' final word, said, "If we'd had Drew Brees, I might still be in Miami."

Brees was at peace. His body and mind were ready. At his introductory New Orleans press conference, Brees boldly allayed any fears about his injured shoulder - cynics had been doubting him all his life. "They'll be eating their words," he said. "It's not the first time somebody said I couldn't do it." His new teammates quickly grew to love him; he addressed them and many came away impressed.

Brittany and Drew moved into a four-bedroom home that was more than 100 years old in New Orleans' Uptown neighborhood. "I love the charm of this place," Drew told the New York Times. "Who knows how long these wood floors have been here, how long these chandeliers have hung here. That is the fun of being in an old house like this."

Brees felt easy in the Big Easy. The Bayou would be built up again. And yes, New Orleans did have tradition: football and family.

"A Grand Slam on Your First Day"

After Further Review: My Life Including the Infamous, Controversial, and Unforgettable Calls That Changed the NFL Mike Pereira with Rick Jaffe (2016)

After retiring as NFL head of officiating, Mike Pereira was immediately hired by the Fox Network to comment on rulings during NFL games.  Mike Pereira

They hire ex-players and ex-coaches to discuss the nuances of the game from their standpoint. But nobody had ever hired an ex-official to explain what the referee might be looking at in a particular situation, be it a replay or a rules interpretation.

So for the 2010 season, Fox built out a little studio inside one of the control rooms for me that had a camera and monitors where we could see every NFL game— not just on FOX but CBS as well. The camera was positioned to where I could be brought into any FOX broadcast live and talk to the announcers about any play in question.

I then hired a bunch of local college and high school officials in Southern California, quite a mix of people, who would each be assigned a game and a TiVo system so they could track every play and penalty called and alert me to something unusual or controversial.

The NFL season arrived on Sunday, September 12, 2010. It was Week 1, and none of us were exactly sure what to expect or how things would play out. If there was a question about the officiating, or a controversy, I would jump on the air and give my opinion quickly on what was going on. Talking in quick, short sound bites is something I had to adjust to because I like to talk.

What happened next, Scorsese couldn't have scripted any better.

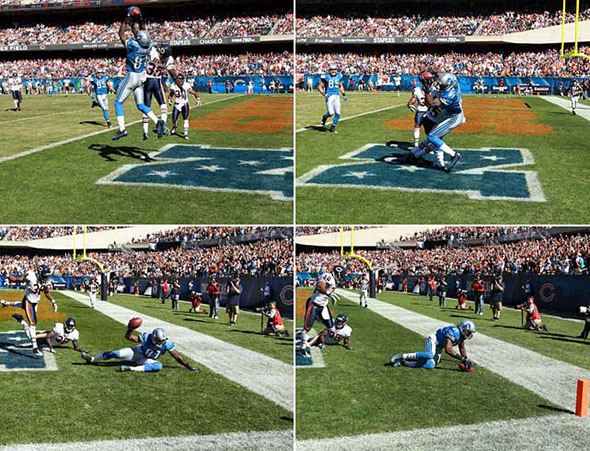

Detroit and Chicago were nearing the end of an exciting game, with the Lions trailing the Bears 19–14. The Lions had the ball second-and-10 at the Bears' 25-yard line, with just 31 seconds left in the game. Quarterback Matthew Stafford launched a pass to the end zone and Calvin Johnson leaped for the ball and made what appeared to be a great catch and a touchdown that could have won it for the Lions.

One official signaled a touchdown and another signaled an incomplete pass. On a quick glance, Johnson appeared to have gotten both feet down inbounds and rolled over before letting the ball go. It would eventually be ruled an incomplete pass on the field, but then it went to a replay review.

It certainly looked like a catch, and the announcers in the FOX booth, Thom Brennaman and Brian Billick, the former Baltimore Ravens coach, were saying as much. It was time to bring in the new kid on the block… me. Butterflies the size of seagulls began flying around in my stomach as they asked me what I thought. It was live television, folks. No pressure.

I told them— and the rest of America— that the rule states that if you're going to the ground you must hold on to the ball when you hit the ground, not yet taking a stance.

They countered that Johnson wasn't going to the ground and I said that he was. We were almost arguing on the air whether it was a catch or not. They countered that Johnson wasn't going to the ground and I said that he was. We were almost arguing on the air whether it was a catch or not. The review was taking an eternity when one of them finally asked me what the ruling was going to be.

Wow. Really? I guess there's nothing like making an impression in your first week. So there I am, expected to make a decision on a game-deciding play on national television, which could quickly turn into either a career-defining or career-ending moment.

If I was right, I was supposed to be. If I was wrong, on what would turn out to be the biggest call of the day, I might have been walking down Pico Boulevard outside the FOX Network Center with a cup in my hand.

I finally got the words out of my mouth and said that the rule states you have to hold on to the ball when you hit the ground. I told them I thought that they would stay with the call of an incomplete pass. I remember hearing Billick in the background yelling, "No way! That's a catch!"

We all watched as referee Gene Steratore came out from under the hood and headed back onto the field to make the announcement. Somebody could have put a bucket under me, I was sweating so much.

"After reviewing the play," Steratore started, "the ruling on the field stands. The receiver did not maintain control of the ball when he hit the ground."

When I heard the announcement, I let out a huge sigh of relief but also felt my knees about to buckle. Good thing my chair was close by.

But that was just the beginning. The Brennaman–Billick argument with me would be a tremor for the volcano that was about to erupt. Fans were going crazy on social media, especially Lions fans, saying the decision didn't make sense.

It really did look like a catch to most people, but it's a very complex rule. However, what I had done — going on television to explain to viewers what the referee was looking at and clarifying why he was going to rule the way he did before he did it — was a significant moment for me… and for FOX.

David Hill [the Fox executive who hired Pereira] had taken a chance on me, doing something no other network had done before, and it was paying off the very first week.

FOX NFL insider Jay Glazer flung open the door to our little control room and shouted, in typical Glazer fashion, "Pereira, you just hit a grand slam on your first day!" As you might already know, despite his small stature, Glazer's personality makes him about 6'9".

"What you did that day and continue to do is a vital service, not only to fans but to the National Football League," Hill recalled of my fateful first week.

e was right. Again. What I did actually deflected some of the criticism away from the officials and placed it on the rule. The league would certainly rather have the judgment placed on the rule rather than on officials. The officials were just going by the rule, so they got the call right. It's the rule that's screwed up.

How about that for a first day? |