|

SEC Legend: Don Hutson

SEC Football's Greatest Games: The Legendary Players, Last-Minute Prayers, and Championship Moments, Alex Martin Smith (2018)

Even as he worked his way toward All-America honors as the nation's best pass catcher, Don Hutson kept his sights on Major League Baseball. The NFL just wasn't sexy enough.

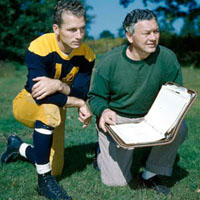

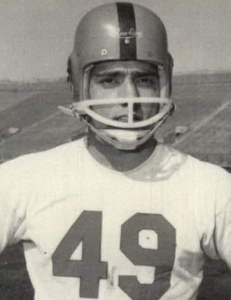

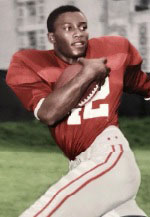

"They didn't even write about it in the newspapers," he said. His high school basketball coach had forced him to play football as a senior. When he showed promise, a pool-hall owner in Hutson's hometown of Pine Bluff, Arkansas, helped him land a spot on Frank Thomas's football team at Alabama. Two bum seasons in the Cincinnati Reds baseball organization - and a two-touchdown showing in Alabama's 1935 Rose Bowl victory - helped steer Hutson toward the gridiron career he kept trying to avoid. The "Alabama Antelope" agreed to sign with the Green Bay Packers, and it was not long before he was the league's best player. "He had all the moves," fellow Packers legend Tony Canadeo said. "He invented the moves." The era's passing game was so undeveloped that simple changes - for example, turning Hutson into a "split end" by lining him up near the sideline - were extremely progressive in the 1930s. Hutson essentially created modern route-running, and coach Curly Lambeau aided his ascension by moving him from the defensive line to safety, thereby helping him avoid big hits on defense. He had too many legendary moments to publish in this space, but here are a couple of the best: In one game against the Detroit Lions, he caught four touchdown passes and kicked 5 extra points ... in one quarter. His record of 29 points in a single period still stands more than seven decades later. In another game against the Cleveland Rams, Hutson was running a crossing route in the back of the end zone when he decided to change directions. Instead of simply stopping and cutting, he grabbed the right goalpost and swung himself around it - both feet off the ground - before making a one-handed touchdown catch.   L: Bear Bryant and Don Hutson, Alabama; R: Don Hutson and Curly Lambeau Green Bay His 488 career receptions were 298 ahead of the nearest challenger at the time of his retirement. His single-season record of 17 touchdown receptions stood for 42 years. His 99 career touchdown catches stood for 44. Hutson led the NFL in receptions eight times, including five consecutive seasons. He led the league in receiving yards seven times, including four consecutive seasons. He led the league in touchdown receptions nine times, including five consecutive seasons. Those are all still NFL records. (He also intercepted 30 passes in his career.) "He would glide downfield, leaning forward as if to steady himself close to the ground," Lambeau said. "Then, as suddenly as you gulp or blink an eye, he would feint one way and go the other, reach up like a dancer, gracefully squeeze the ball and leave the scene of the accident - the accident being the defensive backs who tangled their feet up and fell trying to cover him." Of course, his time at Alabama was scintillating, too. Teammate Paul "Bear" Bryant knew he was watching an all-time great in Tuscaloosa. "In all my life, I have never seen a better pass receiver," Bryant said. "He had great hands, great timing, and deceptive speed. He'd come off the line looking like he was running wide open, and just be cruising. Then, he'd really open up. He looked like he was gliding, and he'd reach for the ball at the exact moment it got there, like it was an apple from a tree." Alabama coach Frank Thomas remembered a player who exhibited plenty of toughness to complement his graceful athleticism. There was an eerie calm about him, too. "Hutson never tightened up," Thomas said. "He was as relaxed in the Rose Bowl as he was in practice." Put simply by former Chicago Bears rival Clyde "Bulldog" Turner upon Hutson's death in 1997: "He was the best I've ever seen. I don't like to compare plaeyrs then with players now. But he was head and shoulders above the ones in that era." Birth of the Split T

Bill Connelly, The 50 Best College Football Teams of All Time(2016)

Missouri head coach Don Faurot created his own version of the T formation to compensate for the loss of star QB Paul Christman.

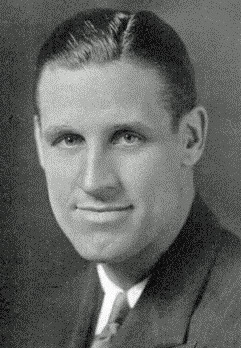

In 1939-40, Pitchin' Paul finished in the top five of the Heisman voting twice and led Mizzouri to the 1939 Big 6 title and the Tigers' first ever bowl bid, a trip to the 1940 Orange Bowl. They averaged nearly 24 points per game in 1940, with Christman leading the way, and the St. Louis native was selected by the Chicago Cardinals in the second round of the 1941 NFL Draft. Christman's presence drove the Missouri offense, and in his absence, Faurot thought he might need to get creative to keep moving the ball. In his 1950 book, Secrets of the "Split T" Formation, he explained: "Christman fit nicely into our single wing and short punt for­mations. ... There was no suitable replacement in sight among returning lettermen. However, our veteran backs had considerable speed, and the squad as a whole was versatile. The time seemed ripe for innovating the basic plays of the "Split T." Mizzou was in the process of upgrading its out-of-conference scheduling. To help pay for athletic department expenses, Faurot, with his athletic director hat on, took a series of payout games. Between 1940 and 1949, the Tigers would play at Ohio State an incredible eight times, at Minnesota three times, and at SMU twice; they would also visit to Pitt, Wisconsin, Fordham, Texas, and Navy. In Secrets, Faurot noted that the deception of the Split T he was tinkering with was attractive because it might allow his guys to compete with bigger, stronger teams. "We needed the deception of the 'Split T' together with its promise of more offensive punch to offset the superior manpower mustered by our opponents. If we couldn't beat them down to size, then we might bewilder them! It was worth a try." Deception was long a part of football offenses, but options weren't. The premise of the Split T was to begin with your run-of-the-mill T formation and spread out the line further, giving them wider splits. Once the defense was spread out, you could find more gaps to exploit with speedy ball-carriers. But Faurot, once a basketball letterman at Mizzou, also saw a way to basically create miniature, 2-on-1 fast breaks. The QB could run the ball to the edge of the defense, and if a defender committed to tackling him, he could pitch the ball to a trailing halfback. Faurot may have been the first college football coach to commit to option football. With film study still at a minimum, Missouri was able to constantly fluster unprepared opponents with it. He unveiled the offense in the second half of the 1941 opener against Ohio State, and while it was too late to help the Tigers against the Buckeyes in a 12-7 loss, the Tigers would proceed to go 16-4-1 over the next two seasons, 9-0-1 in Big 5 Play. They reached the Sugar Bowl in 1941 and went 8-3-1 in 1942 ... They finished the 1942 season with one of the most impressive wins of the Faurot era: a 7-0 win over the Iowa Pre-Flight Seahawks in a Kansas City snowstorm.     Don Faurot, Paul Christman, Bud Wilkinson, Jim Tatum Football already had a grip on the country's consciousness, and many believed that it could be a useful tool within the armed forces - it helped to toughen men up, taught teamwork and discipline, etc. Beginning in 1942, teams from various Army camps and Navy bases began to play full sche­dules against not only each other, but also local college teams, many of which consisted of freshmen (who were previously ineligible to play) and/or players who were denied entry into the service for one reason or another. These military teams frequently used recent college football players and sometimes even included a smattering of pros. Quite a few of these teams existed, and a few played schedules against mostly top-division schools. ... In 1943, for instance, teams like Nebraska, Pittsburgh, TCU, Yale, Wisconsin, and Georgia were all varying degrees of awful, while Iowa Pre-Flight, Great Lakes Navy, Delmonte Pre-Flight, and March Field finished ranked in the AP poll at the end of the season. Meanwhile, non-powers Tulsa, Dartmouth, Colorado College, and Amos Alonzo Stagg's Pacific also finished ranked. ... These service teams were coached by real, well-known college football coaches. Minnesota's Bernie Bierman, for instance, led the Iowa Pre-Flight team in 1942. When he was assigned elsewhere, another new enlistee took the reins in Iowa City: the 41-year-old Faurot. Mizzou's head man spent a year with Iowa Pre-Flight, then took over Jack­sonville N.A.S. in 1944. You could legitimately say that Faurot's lone season with Iowa Pre-Flight changed college football. It's not because the Seahawks were good - though they certainly were - but be­cause of the proliferation of the Split T. Among Faurot's assistants on the 1943 Seahawks: Bud Wilkinson and Jim Tatum. ... Faurot was not a secret keeper. He could have leaned on his single wing and "short punt" formations while at Iowa ... Instead he shared with his young assistants the ins and outs of his new baby, the Split T. For football itself, this was great. This became a staple of many a college offense over the next couple of decades, and not necessarily because of Faurot. In 1946, after the war, Oklahoma hired Tatum as its new head coach, and Tatum brought Wilkinson along as an assistant. After one 8-3 campaign and Gator Bowl title, Tatum was pulled away by Maryland, and OU promoted Wilkinson. Tatum would win 73 games in 10 seasons at Maryland, finishing third of better in the AP poll three times and winning the 1953 national title. Wilkinson, meanwhile, coached for 17 years in Norman, won 145 games, finished in the AP top five 10 times in 11 years, and claimed shares of three national titles (1950, 1955, 1956). Both Tatum and Wilkinson were better recruiters and perhaps better overall head coaches than Faurot; the tactical boost they got in Iowa City pushed both of their respective ca­reers into the stratosphere, and they left their one-time mentor behind Faurot. Faurot would go on to reach two more bowls after the war, but he went an incredible 0-17 against Tatum and Wilkinson. The final loss of his career, in fact, was a 67-14 shellacking in Norman. The NFL's Space Ship Division

Richard Bak, The Coffin Corner (May/June 2020)

Foortball coaches are always looking for an edge, and new technology often provides it. In the early stages of the 1956 season, several teams, led by rivals Cleveland and Detroit, rolled out an innovative messaging system that was a glimpse of the National Football League's future. For the first time, selected players were "wired for sound" - outfitted with miniature radios that allowed them to receive signals from the bench or the press box.

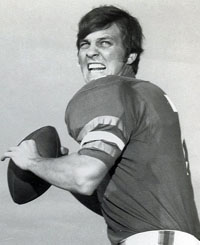

Unsurprisingly, the pioneer was Paul Brown. The Cleveland coach had been fooling around for years with the idea of using radio signals to more efficiently send plays to his quarterback, instead of relying on his usual system of messenger guards and backs. According to a source, at one point Brown "actually got a radio in Otto Graham's helmet. Then he experimented at League Park and Cleveland Stadium. Brown broadcast from the bench while Graham ran to all corners of the field, wig-wagging the results." It wasn't until September 15, 1956, in the second of back-to-back preseason games with the Lions, that Brown field-tested the system against a real opponent. The helmets of quarterbacks George Ratterman and Vito "Babe" Parilli were each outfitted with a receiver about the size of a pocket watch. Brown, who had to obtain a shortwave license to operate the radio, used a four-watt transmitter and microphone to send plays from the bench. There was no difference in the outcome. A week earlier the defending champs had lost to Detroit, 17–0, without Brown's gizmo, and on this occasion they were whipped by the same seventeen-point margin, 31–14, with it. "There is some speculation that quarterbacks Ratterman and Parilli might have picked up some short-wave police calls, some dance music, or an SOS from a stricken fishing boat off the coast of New Zealand," wrote a bemused Lyall Smith in the Detroit Free Press. Actually, Ratterman spent much of the stormy evening in Akron fearing for his life. In addition to the head-hunting Lions targeting the contraption in his helmet, there were the occasional flashes of lightning that he admitted "scared the hell" out of him by threatening to fry his electronic ears.     L-R: Paul Brown, Otto Graham, George Ratterman, Babe Parilli    L-R: Bobby Layne and Buddy Parker, Joe Schmidt, Bert Bell Notre Dame Shatters Oklahoma's

47-Game Winning Streak Fred Eisenhammer and Eric Sondheimer, College Football's Most Memorable Games (1992)

November 16, 1957 It was vindication for Notre Dame Coach Terry Brennan.

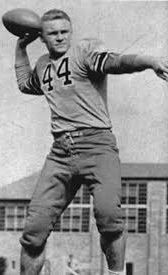

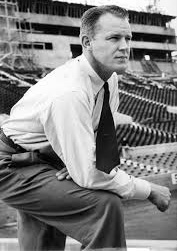

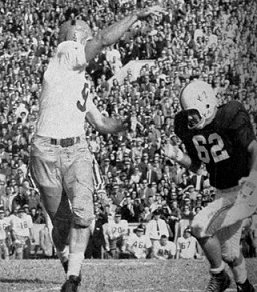

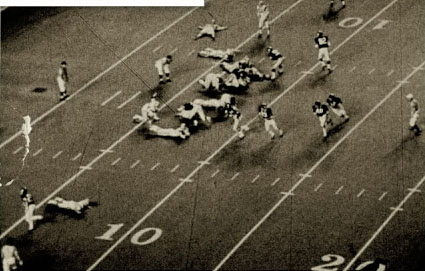

With their fourth-year coach under fire, the Fighting Irish turned in a rousing effort to shatter heavily favored Oklahoma's 47-game winning streak - college football's all-time record - with a stunning 7-0 victory before 63,170 fans in Norman, Oklahoma. HB Dick Lynch's 3y touchdown run on fourth down late in the fourth quarter broke a scoreless tie and allowed Notre Dame to break a two-game losing streak. For Brennan, it was a sweet victory. Brennan's Fighting Irish had lost to Oklahoma 40-0 in South Bend the previous year - a season in which they registered their first losing record in 24 years with a 2-8 mark. Furthermore, the Fighting Irish had just dropped back-to-back games to Navy and Michigan State in one-sided fashion before heading to Norman and almost certain defeat against the nation's second-ranked Sooners, who had won their first seven games of the season. But Notre Dame (5-2) pulled out of its tailspin behind a rock-ribbed defense that stopped the two-time defending national champion Sooners' run-oriented offense cold and an offense that mustered an 80y touchdown drive in the closing minutes.    L-R: Carl Dodd runs for OU; ND QB Bob Williams passes; Bud Wilkinson dejected on the sideline.

Oklahoma, which had been averaging 300y a game, was held to 98y on the ground and 47 in the air. Clendon Thomas was Oklahoma's leading ballcarrier with 36y in 10 tries. "Oklahoma was a fine football team," Brennan said. "And Bud Wilkinson was a fine football coach. But he was predictable and we felt if we could stop their four or five basic plays, we had a chance to win. And we did." One of Oklahoma's biggest weapons was the punting by Thomas and David Baker, who kept Notre Dame bottled up near its end zone in the third quarter. But the Sooners could not capitalize. "I was willing to settle for a scoreless tie in the third quarter," said Wilkinson afterward. "I felt at the start of the second half we had a good chance. But after we couldn't get going, even with our tremendous punting to their goal, I was ready to settle for a scoreless tie." Oklahoma's best scoring threat came in the first quarter when the Sooners drove to Notre Dame's 13 before they were held on downs. "They were just better than we were today," Wilkinson said. "They deserved to win." Notre Dame not only stopped Oklahoma's winning streak, but the Irish broke the Sooners' national record of scoring in 123 consecutive games. Interestingly, Notre Dame was the last team to defeat Oklahoma, defeating the Sooners 28-21 at the start of the 1953 season. Oklahoma was tied, 7-7, by Pittsburgh in its next game before beginning its amazing streak. Brennan, a former three-year starting running back at Notre Dame, often called the streak-stopping victory over Oklahoma "the greatest thrill of my athletic career." Brennan coached the Fighting Irish for five seasons, compiling a 32-18 record. Pietrosante distinguished himself as a stellar running back for the Detroit Lions.   L-R: Nick Pietrosante; Coach Brennan carried off. Doug Atkins: One-Man Pass Rush

1968 Saints @ Lions Game Program

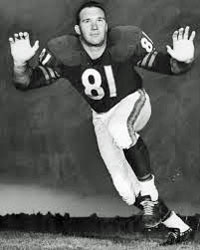

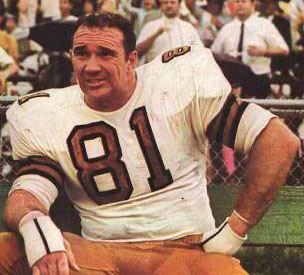

At 38, an age when defensive linemen are supposed to be so far over the hill you couldn't find them with a telescope, the Saints' Doug Atkins is having one of his best seasons ever.

Atkins, in his 16th National Football League season, is having a grand time hitting his licks. The mountainous man from Tennessee is so important to the second-year Saints that their defensive unit has been named Atkins' Army. He's the supreme figure. Any defender in the ranks who is caught loafing knows he must answers to the 6-foot-8, 275-pound Atkins, an amazing athlete who has pushed himself far past normal expectations. The younger Saints have a great deal of respect for Atkins. Defensive tackles Dave Rowe and Mike Tilleman are in their second and third pro seasons, respectively. One day they appeared at practice with private's stripes on their jerseys, marched briskly before Atkins and saluted. They should have. He was playing in the NFL when they were in grade school. Atkins is a large reason that the Saints have won three games this season - most ever for a second-year expansion team. Also, he's an important reason that the Saints are leading the NFL in pass defense. Saints coach Tom Fears is impressed. "I don't know what it is that keeps him going," says Fears, "but there's no telling how long he'll go on. When we traded for Atkins we figured to get one season out of him. But now, I just don't know. He just keeps going on and on." Saints defensive back Dave Whitsell, an 11-year veteran, predicts Atkins will play next season, too. "This man is unbelievable," says Whitsell. "He's got another year or two left." Atkins isn't talking much about the future. "I'm just playing it game by game now," says Atkins. "I consider myself lucky to play as long as I have and I just hope all my injuries are history by now." "Retirement is something you never really think about, but you know it's got to come someday." Cleveland drafted Atkins No. 1 when he finished at Tennessee in 1953, and he spent two seasons with them before being traded to Chicago, where he made All-NFL six times, but was unhappy doing it. George Halas' frugality frustrated him. Finally the opportunity to escape came the past year, when the Saints traded for him. This might have seemed too late for an aging lineman who would have to carry an extra-heavy load with an expansion team, but Atkins responded with the vigor of a rookie. He left his mark wherever he played.   L-R: Doug Atkins with Bears, Doug Atkins with Saints Perhaps the change of scenery had made Atkins feel younger than his years. "Coming to the Saints has helped my attitude," he says. "I've had ideal working conditions in New Orleans. The management, the coaches, everyone down the line has treated me just great. STOP? "I had asked Halas for years to trade me. It got to the point where I had just about given up hope when the Saints' deal came along. "I wish I could have hooked up with a club like this 15 years ago. With Halas, I had to fight and argue for a $1,000 raise. With John Mecom Jr., it's entirely different. "One year it cost me $900 for nine days of arguing. I had signed a two-year contract, but after the kind of year I had, I thought some adjustment should be made. I found you either played for what they offered you or forget it. Football is tough enough without having to deal with people who won't meet you halfway." STOP? Happy now with his treatment by Mecom, the wealthy young owner of the Saints, Atkins plays a fierce game in which he meets no one halfway, particularly the quarterbacks. "I think quarterbacks are well paid to take the beatings they do," judges Atkins. "Defensive linemen take their bumps and bruises and nobody worries about us." STOP? The big man has known his share of pain, all right. Atkins has had two knee operations, broken his collar bone, suffered numerous cracked ribs, ripped groin muscles, broken both hands, sprained both ankles and torn a bicep that required surgery to repair. "When you consider Doug's career," says Fears. "It's incredible he's still around." All of these miseries have not made such a great impression on Atkins, however. "The toughest part of the game is not the physical punishment you receive from the actual contact," he says. "Rather it's the constant fatigue you must fight, draining yourself every play. Pushing and pushing. Your body is conditioned to absorb knocks, but no matter what shape you're in, there are so many factors which tend to tire you out. "Look at it this way: If someone hits me a good lick chances are I won't even feel it until the next day. But do you realize how much it takes out of a man every time he tries to hand wrestle or pick up a 250-pound lineman?" Whatever it takes, the one-time all-state and semi-pro basketball player has more than enough to keep going. He played a grand game in the season's opener against Cleveland, making 13 unassisted tackles. The Saints lost, but Atkins was so tough he was named NFL Defensive Player of the Week by the Associated Press. But maybe he had a grudge against Cleveland. After all, that's the club that traded him to Chicago 13 years ago. Woody the Perfectionist

War As They knew It: Woody Hayes, Bo Schembechler, and America in a Time of Unrest,

Michael Rosenberg (2008) With the exception of his military service, Woody Hayes lived his entire life in the state of Ohio. He grew up in little Newcomerstown, on the east side of the state; attended Denison University, 32 miles outside Columbus; and only coached in the state. Hayes was proud of that. he felt that Ohio represented all that was great and pure about America ...

The Ohio State Buckeyes were more than just a local team. They were the prism through which Columbus viewed itself. The passion was so great that it had consumed the three men who coached before Hayes; Paul Bixler, Carroll Widdoes, and Wes Fesler had all resigned at least partly because of the intense pressure, earning Ohio State its tag as the "graveyard of coaches." Hayes had survived for 18 years in Columbus. By 1969, coming off one national championship with another one surely on the way, he had raised his profile. He was not just the head coach at Ohio State. To many, he was Ohio State. Hayes understood instinctively that the key to longevity in Columbus was beating Michigan. In 1934, Ohio State coach Francis Schmidt had spoken for his whole school when he said the Michigan players "put their pants on one leg at a time, the same as we do!" Since Schmidt's declaration, any Buckeye who beat Michigan received a miniature pair of gold pants. While other coaches fled from that pressure, Hayes elevated the rivalry's importance. He made it clear that the Ohio State-Michigan rivalry was not just between schools but between states. He said the rivalry started in 1836 when President Andrew Jackson forced Michigan to cede Toledo to Ohio in order to gain statehood. (133 years later, Toledo was still split territory: Michigan fans were as prominent in the city as Ohio State fans.) Hayes was famous among fans and reporters for never saying "Michigan" - he always called it That School Up North. This was not just a show for the public. Hayes's players and assistant coaches never heard him say the word "Michigan." It was always - always - That School Up North. Some figured this was just a motivational ploy. Others believed that Hayes had a certain disdain for Michigan, which thought of itself as a "public Ivy," academically superior to other Big Ten schools. (By 1969, Ann Arbor's radical bent surely didn't endear the town to him.) Whatever Hayes's true feelings, his public comments clearly made him more popular in Columbus. ...     L-R: Woody Hayes, Francis Schmidt, "Gold Pants" Award, Paul Warfield In 1961, Ohio State had no more than a dozen offensive plays - that's all the Buckeyes ran for the entire season. That meant that in a given game, every play would be called a few times, and his favorite plays (basic off-tackle runs) were called so often, everybody in the stadium could recognize them. The team had Paul Warfield, who would go on to make the Pro Football Hall of Fame as a wide receiver - but Hayes put him at running back and defensive back, and Warfield barely caught any passes.

When he wanted to pass that season, Hayes would often remove his normal running quarterback for a superior passer, telegraphing his play preference to the other team. Ohio State used a single snap count the whole year - when the quarterback shouted "Go!" the center would snap the ball. Naturally, opposing defenders figured this out rather quickly. "They're snapping it on 'Go!'" they told each other excitedly, as though they had just cracked some top-secret code. The Buckeyes would just laugh. They had reason to. That year, with a dozen offensive plays, gross misuse of one of the best receivers in football history, and the most obvious snap count imaginable, they won the national championship. And they won it largely because of coaching. Hayes demanded that his players repeat a technique one thousand times, until every muscle and joint moved in precisely the right way. Then he would make them do it again. He wanted to take the entropy out of the game; he loathed fumbles, penalties, and any other mental errors, and his teams seldom made mistakes. If every man executed his individual assignment better than the opponent, then Hayes's eleven would outplay the other coach's eleven on that play - and if that happened repeatedly, his troops would march down the field efficiently. Patton said wars were fought with weapons but won by men. Woody Hayes let others invent new weapons. He made sure he had the best men. His players quickly discovered that it was enough to perform the same technique again and again; Hayes wanted maximum effort on each attempt. To that end, he used extreme motivational techniques. If a player made a mistake in practice, Hayes often hit himself in the head - not just the occasional slap to the forehead, but all-out punches to the face. At other times, he would take off his glasses and step on them (he went through a dozen pairs a year) or take off his watch and break it. Players suspected that some of it was an act - there were whispers that Ohio State trainers cut Hayes's hats before practice, to make them easier to test later - but they knew it wasn't all an act, and part of Hayes's genius was the mystery. Players could never quite tell when he was acting and when he had lost his mind. It was not the sort of question one asked. The "Heidi" Game

Gang Green, Gerald Eskenazi (1998)

The Jets' game in Oakland during that 1968 season saw such bizarre, nutty, funny circumstances that it became a permanent part of sports lore. The Jets-Raiders affair came to be known simply as the "Heidi" game. ...

The Jets and Raiders met in Oakland for an unofficial playoff preview, the Jets with their four-game winning streak, the Raiders with three in a row. Before the game, one of the game officials asked Dr. Nicholas [the Jets' team doctor] to take a look at his bad back. This Nicholas did, and then promised to return when the game was over to check it out again. The game turned into a brutal, penalty-laced affair, with players pounding one another and points lighting up the scoreboard. The Jets went ahead by 32-29 on [Jim] Turner's field goal with 65 seconds remaining. But it was also close to 7 P.M. in the crowded, TV-saturated East. And at seven o'clock eastern time, a made-for-television movie, Heidi, the story of the little girl in the Swiss Alps, was scheduled to appear on NBC. ... What harm, thought NBC officials, could there be in leaving the game after a commercial? The Jets were about to win. Someone in the control room calculated that 10 seconds would be sliced from the clock on the kickoff. There wasn't enough time in 55 seconds to make a difference. So the network cut away from Oakland and shifted to Heidi. From his home, Allan B. (Scotty) Connal, the head of NBC Sports, immediately sensed this was not a good idea. He tried to persuade the technicians on duty not to switch from those last seconds of the late-running game. But he couldn't get through to anyone who mattered, and Heidi it was. When the 11 o'clock news went on that night, fans heard for the first time the unbelievable final score: Oakland 43 Jets 32. While they weren't watching, the Raiders had scored 14 points. Raiders QB Daryle Lamonica connected twice with RB Charlie Smith, who outfoxed rookie SS Mike D'Amato. First, Smith gained 20y, with a D'Amato penalty tacked on. The next play, Smith took a swing pass and scampered 43y for a TD.    L-R: Dr. James Nicholas, Walt Michaels, Weeb Ewbank Now, with 42 seconds remaining, the Raiders led by 36-32. Only a touchdown would win it for the Jets. Then again, with [QB Joe] Namath and [receivers Don] Maynard and [George] Sauer, it didn't seem impossible. But Earl Christy fumbled the kickoff, chased it back to the 10, lost it again, and watched it slither to the two. From there, a fellow named Preston Ridlehuber, who was never to play another season for the Raiders, scooped it up and ran in for the TD. Two scores, nine seconds apart. No one back in New York knew this, though. An hour after the game, Weeb telephoned his wife, Lucy, back in New York. "Congratulations," she told him. "For what?" said Weeb. "On winning," she replied. "We lost the game," said Ewbank. Of course, Weeb was hardly alone in not realizing how New Yorkers were reacting to what happened. The Jets did not return home after the game because they had a game in San Diego the following week; as was the custom then, with consecutive West Coast games, the Jets simply spent the whole week in California. So after the game, they flew to Long Beach. When the players turned on the late news, they learned that the NBC switchboard in New York had been knocked out of commission by thousands of callers. Some of the outraged fans had actually telelphoned the police to find out what had happened. If fans were irate over not knowing what had happened, imagine how teed off the Jets were, who did. When the game ended, [defensive coordinator] Walt Michaels was still seething over Hudson's ejection. He believed it cost the Jets the game. So did Dr. Nicholas. They headed for the officials' room. The door was locked. Walt started to bang on it, abetted by the doctor. "Walt was yelling his head off," recalls Nicholas. "I went along with him. I thought I'd see the official I had examined and give him a piece of my mind and take a look at his back." Nicholas complained while examining his patient. The next day, the league sent a letter to the Jets telling them that Nicholas was fined $2,500 and Michaels $5,000. The official, who got a free diagnosis, had turned in the good doctor. "I'm the only team doctor in history ever fined for banging on the door," Nicholas likes to relate to this day. ... The next day, the network's program director, Julian Goodman, issued a public apology for "a forgiveable error committed by humans who were concerned with the children." A noble sentiment, indeed. But nobility gave way to practicality as NBC and the NFL altered their policy. Now, whenever a game is shown in either team's home market, it stays on to the end, regardless of the score. Even if the children will miss a kiddies' movie. The Gator Flop

Tales from the Gator Swamp: A Collection of the Greatest Gator Stories Ever Told, Jack Hairston

Perhaps the most famous play in Gator history was the Gator Flop against Miami in 1971. I never saw anything like what happened in the final minutes of the Gators' 45-16 triumph over the Miami Hurricanes in Orange Bowl Stadium.

This was the situation: The Gators had sloughed through a 3-7 season up to the Miami game. John Reaves, Carlos Alvarez, Tommy Durrance and other members of the sophomore class in the spectacular 1969 season (9-1-1, including a Gator Bowl victory over SEC champion Tennessee) weren't happy seniors in '71. The beatings had been severe, and several players were still disgruntled that Tennessee Coach Doug Dickey had succeeded Ray Graves as Gator coach after the '69 Gator Bowl meeting. Miami was a slight favorite going into the '71 game in its first season under former Miami QB Fran Curci, an avowed Gator hater. Reaves, going into the final game of his college career, was within 344y of the national career passing record held by Jim Plunkett of Stanford (7,545y). That seemed to be a nearly impossible reach for Reaves, who had averaged 290 passing yards per game in '69, 232 yards in '70 and was averaging 176y going into the Miami game. ... The two leading characters in this drama were to be Curci and Reaves, who didn't like each other. The year before when he was head coach at the University of Tampa, Curci had described the Reaves-led Gators as crybabies. Reaves had expressed his displeasure about Curci. Now they were opponents as Reaves took aim at one of the game's top records.  .jpg)  L-R: John Reaves, Doug Dickey, Fran Curci "Harvin came into the huddle," Clifford said, "and told us, 'Coach says to let 'em score! We're all going to lie down!' I didn't flop, but I've been told that I stood up on the play, and that isn't so. I went down to one knee and didn't make a move to make the tackle. "I've looked at some pictures of the play, and one of our players WAS standing up, but it wasn't me. I don't know who it was. I've been told I tried to make the tackle, but I didn't do that either. What I remember best is the look on (Miami QB) John Hornibrook's face when he rolled out and saw all those people on the ground. He hesitated a moment, and maybe his instincts took over, and he kind of walked across the goal. I've often wondered how weird it would have gotten if he had declined to score the TD and had run back up the field with the ball. That play might have gone on a long time.  The Gator Flop "The coaches turned John loose a little more than usual in that game," Clifford said. "Let him throw more. But I'll always believe we could have done it better on the laydown play ... done it without embarrassing anyone. But I never considered myself any better than anybody else because I didn't flop. There was a lot of frustration on that team. We'd had a lousy season, and we weren't going to a bowl game. The frustration of the whole season came out that night. Also, I remember a lot of enthusiasm among the players before the game about John having a shot at the record. "When the game was over, I don't know who started it, but we all ran down behind the end zone where the pool was for the Miami Dolphins' mascot, Flipper. We all jumped in the water and just splashed around, whooping it up." ... Curci has devoted a lot of his life since that night to criticizing the Gator Flop. He had much to say about it from that night on. For years I thought Curci just saw an opportunity to get the spotlight off him and his team's poor performance. Miami was favored in the game and lost by a 45-16 score, and Curci installed a new offense the week of the game (the wishbone) and moved Miami's great RB, Chuck Foreman, later a longtime NFL star with the Minnesota Vikings, to flanker, where he didn't carry the ball a single time. My thought was Curci was standing on the sideline with about a minute to play, thinking how he was going to be criticized, when the laydown play presented itself ... and presented Curci with a substitute scapegoat for everyone to focus on. People who have coached with Curci tell me, "No, he was really bitter about the laydown play, and many years later he was still cussing Dickey and blaming him for it." "Have you ever seen anything like that in your life?"

Don Shula: A Biography of the Winningest Coach in NFL History, Carlo DeVito (2018)

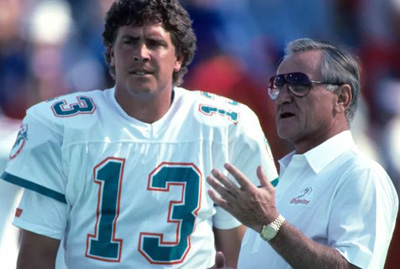

The 1983 NFL Draft was arguably the richest singular draft in the history of the NFL. Everyone knew it would be special, but it would take the league a generation to see how much so. ...

Quarterback John Elway of Stanford was the big prize. Other candidates were fellow signal-callers Jim Kelly, Tony Eason, Todd Blackledge, and Dan Marino. Marino had been the absolute undoubtable star of the 1981 season, his junior year at Pitt, but his senior year was a flop in 1982, and his stock had fallen. The problem was simple for the Dolphins. Who would be available with the 27th pick? They had gone to the Super Bowl and lost, and now they would get to pick second-to-last in the draft. Shula felt for sure no quality quarterback would be left at the end of the first round. As the draft drew near, he focused on Mike Charles, a defensive lineman from Syracuse. The story how Marino fell so badly is still legendary. In 1982 and 1983, there had been rumors that he was using drugs. Were they true? "It was certainly out there that there were 'issues' with Marino," said Ray Didinger of the Philadelphia Daily News. Chuck Noll, a decade after the draft, admitted the Steelers had passed on Marino because of those rumors. "It started off with just the idea that he was partying. Then it grew more sinister from that," Didinger recalled. "I never took any tests," Marino said later. "One time somebody wrote that, but that's something I can't control. If I worried about everything that was written about me, I wouldn't have a good time." Foge Fazio, Marino's head coach his senior season, later admitted to the press that he felt vindictive gamblers started the rumors. "A lot of it was disappointment we didn't beat the point spread," Fazio said. "That's where the viciousness came out." As expected, Elway went No. 1. ... Todd Blackledge of Penn State was the next quarterback picked at the No. 6 spot by the Kansas City Chiefs. Jim Kelly of Miami went to the Buffalo Bills at No. 14, and Tony Eason of Illinois went next at No. 15 to the New England Patriots. "It's a weird day, really," Marino remembered. "You're sitting there ... I know it's football, you're going to play in the NFL, but every other kid that graduates college and has a chance to get a job, they kind of know where they're going or what their profession is going to be or what they're going to do, and you can sit there and not know if you're going to be in Seattle or Miami or Arizona. That part is tough, I think." Added Marino later, "I just remember it being a long day." "People started finding reasons to not like Marino, and I think that the drug rumors were just another thing that they threw on the pile," agent Marvin Demoff said.   L-R: Dan Marino, Don Shula, Foge Fazio Also in the Miami Herald, Edwin Pope wrote, "The word from Marino's hometown is that the Panthers' all-time passing leader declined last year as a twin result of a) inflated ego, and b) pressing to impress the pros after he finished fourth in Heisman Trophy voting as a junior. He developed the idea that he was God's gift to football. Dan was a down-home Pittsburgher who started thinking he was Joe Namath. It hurt the team, along with some other things, like losing some top receivers and also that head-coaching switch-over from Jackie Sherrill to Foge Fazio." "This happens in a lot of drafts," Didinger said. "Once a guy starts falling, everybody runs the other way. Everyone assumes everyone else knows something, and they back away." "People were scared that they couldn't handle him," said one NFL scout later. "Why waste a No. 1 on a problem?" At No. 24 in the first round, the Jets were on the clock. Days before, Fazio, a good friend of Jets head coach Joe Walton, who had just replaced Walt Michaels, called to vouch for Marino. As the tension mounted, Jets fans in the balcony of the New York Sheraton hotel, where the draft was conducted, could be heard chanting loudly, "Dan Marino! Dan Marino!" Commissioner Pete Rozelle announced, "With the 24th pick, the New York Jets select quarterback ..." There was a pause. "I don't think Rozelle did it on purpose. But for dramatic effect, he couldn't have done it better," remembered Didinger. "Ken O'Brien, University of California-Davis," Rozelle finished. "The cheers turned to screams of anguish - and then boos, in just a second," Didinger said. The Bengals and Raiders also passed on Marino, and then came the Dolphins at 27. (Miami D-coordinator) Bill Arnsparger pushed Shula hard to take Charles. "The pressure was on me to take the defensive lineman," Shula recalled. Future Hall of Fame defensive back Darrell Green was also on their list of available players. "Everybody's trying to figure out now why he was drafted so late," said Shula. The Dolphins head coach was thrilled to find Marino available. "We had a strong commitment to Marino that others did not. We heard rumors, different kinds of rumors. We checked them out and did not hear anything that changed our minds. I called Foge Fazio, and he gave me his strongest recommendation. We knew all we needed to know." ... With our situation and our evaluation of Dan Marino, we felt he was a good pick," said Shula. "Certainly good credentials. Didn't have the best senior year, but when you look at him and evaluate him throughout his career, you have to be pretty impressed." "What Shula saw was a franchise player who could carry a team for a decade or more. He saw an already polished drop-back passer who had spent four college seasons in a pass-oriented offense. He saw the MVP of both the Senior Bowl and Hula Bowl who had thrown for 8,416 yards and 79 touchdowns at Pitt," wrote Paul Attner in the Washington Post. "I was happy the Dolphins got me," said Marino. "This is all I've wanted to do, to get a chance to play in the pros, and Miami is giving me this chance. Everything else is behind me, and I let it go at that." "You probably got the best guy in the draft," said Chuck Noll to Shula by phone after the Dolphins picked Marino. There was a story that was oft repeated in Miami sports circles in the subsequent years. Shula was quiet as he watched Marino work out for the first time that spring of 1983. Shula was sure he'd gotten a "steal" in the draft, though how much of a steal he wasn't sure. "Shula stood behind Marino, watching him effortlessly flick pass after pass, using not much more than his wrist. He looked like a man fly-casting with a fishing rod, but the ball would zing downfield 40 to 50 yards. Then Shula did something he almost never does. He walked to the sideline to chat with a friend, Edwin Pope, sports editor of the Miami News," remembered sportswriter Larry Felser. "Have you ever seen anything like that in your life?" Shula asked Pope quietly. Bye Bye, Parcells

Guts and Genius, Bob Glauber (2018)

Bill Parcells was completing his first season as head coach of the New York Giants in 1983. The consensus was unanimous: Bill Parcells had to go.

The Giants were staggering to a 3-12-1 finish in Parcells's first year as the Giants' head coach, and memories of the darkest years of the franchise were haunting the Mara family. Team president Wellington Mara had presided over the lost years of 1964–1978, when the Giants had gone from a consistent championship-contending team to a franchise besmirched by failure. Rock bottom had come on November 19, 1978, when the Giants were seemingly headed toward victory over the Eagles at Giants Stadium and simply had to run out the clock in the final seconds against an Eagles team with no time-outs remaining. But rather than having quarterback Joe Pisarcik do the sensible thing and take a knee, offensive coordinator Bob Gibson inexplicably called for a handoff to Larry Csonka. The ball caromed off Csonka's right hip and was scooped up by Eagles defensive back Herman Edwards, who returned it for a 26-yard touchdown to give Philadelphia a 19–17 win. Gibson was fired the next day, and during the Giants' next home game, a small plane flew over the Meadowlands carrying a banner: 15 YEARS OF LOUSY FOOTBALL— WE'VE HAD ENOUGH. Watch the fumble play ... The fallout from a play referred to by Giants fans simply as "The Fumble" eventually led to the hiring in 1979 of George Young as general manager, a compromise choice that was acceptable to Wellington and his nephew Tim. The two were not on speaking terms but had agreed to Commissioner Pete Rozelle's recommendation of Young, then a personnel assistant with the Miami Dolphins. Ray Perkins was Young's choice to become head coach in 1979, but when Perkins left in 1982 to coach at the University of Alabama, Young appointed Parcells, a promising defensive coordinator under Perkins. But by December of Parcells's first year on the job, it became clear to all three of the Giants' decision makers that a change had to be made. "Parcells gets hired in 1983, and really the only basis upon which he was hired was that he had some head coaching experience, which wasn't a heck of a lot," said John Mara, Wellington's oldest son and now the team's president and co-owner. "We come to the end of that season, and the jury is very much out on Bill at that point." It was an excruciating season in every possible way, and not simply because of the final record. Parcells had misjudged his quarterback situation, anointing Scott Brunner over former first-round pick Phil Simms. More than two dozen players wound up on injured reserve. After getting off to a 2-2 start, the Giants lost ten of their next twelve games. Parcells's personal loss that season was incalculable. His mother, Ida, had died in December. His father, Charles, had died two months later. His running backs coach, Bob Ledbetter, suffered a stroke in late September and died less than three weeks later. "Both my parents died. My backfield coach died. Hey, it was tough, but that's still no excuse," Parcells said, looking back on the most difficult year of his life. "Listen, they'd seen enough. Everyone was on board with it." The decision had been made: The Giants would look for a new coach. Howard Schnellenberger was their man. Parcells was as good as gone. ...    L-R: Bill Parcells, George Young,Howard Schnellenberger Schnellenberger was the hottest coaching prospect out there, and the Giants were in disarray. Rock bottom came on December 4, when the Giants lost to the lowly Cardinals, 10– 6. Only 25,156 fans showed up at Giants Stadium, meaning there were more than 50,000 no-shows. But when Young reached out to Schnellenberger, the coach told him the timing wasn't right and that he wouldn't take the job. ... "I can't get him this year," Young told the Maras, "but I may be able to get him next year." The Giants decided to give Parcells one more year to turn things around, and if the team continued to flounder, Young would try Schnellenberger again.

...

Parcells's first major move was hiring a strength and conditioning coach, and he settled on a noted college trainer named Johnny Parker. Parker was on the cutting edge of training techniques at LSU and Ole Miss, even traveling to Russia to study what had then been considered the world's most advanced weightlifting program. Parcells was desperate to improve his team's collective health after a hellish run of injuries the year before, and Parker told him he could help. ... Parker took the job, and thereby gained insight into how Parcells was going to handle his team moving forward. "Last year, I tried to be the head coach of the Giants, and that didn't work," Parcells told Parker. "This year, I'm going to be Bill Parcells. If the players get me, they get me. They're going to get me doing it my way." ... Parcells knew he could win only if he had players who were completely committed to winning and to making the sacrifices— both physically and personally— to turn the team around. Young had drafted linebackers Carl Banks, a first-round pick out of Michigan State, and Gary Reasons, a fourth rounder out of Northwestern State of Louisiana, to replace Kelley and Van Pelt. And with nearly two dozen other players dropped from the team, the coach was starting to feel like he had enough of the "my guys"– type players to at least have a chance of winning. And Parcells drove them hard. "Those 1984 players, they're the ones that went through a torture chamber, because I had a whole new attitude, a resolve," Parcells said. "I was close to being over the edge in terms of pressuring these guys, practicing hard, contact, training camp. No fuckin' around."    L-R: Carl Banks, Gary Reasons, Phil Simms

Simms could tell the difference in Parcells's demeanor as soon as he interacted with the coach after the 1983 season. "Bill changed from '83 to '84," Simms said. "He became Bill Parcells, this tough, acid-mouthed guy, and whatever came out of his mouth was the truth. He did it with sarcasm and humor, but it still drove the point home. It just changed us. Right from the start, we were a changed team. You could see it."

Once training camp began, Parcells was unrelenting. He had his players practice in pads six days a week, twice a day— which was actually standard operating procedure for most teams, but with Parcells, he was particularly brutal. If Parcells was going down— and there was that very real possibility, especially if he got off to a poor start— he would do so on his own terms. Postscript: The '84 Giants started 3-3, then won three of their next four on their way to a 9-7 record and a playoff berth. They beat the Rams in the first round before losing to the 49ers, who would win the Super Bowl. Parcells coached the Giants eight years, winning the Super Bowl in 1986 and 1990. |

Lynch touchdown run.

Lynch touchdown run.