|

AFL Tales - 1: The First Game

When the Grass Was Real, Bob Carroll (1993)

At a few minutes after 8 P.M., on Friday, September 9, 1960 ... Tom Discenzo did something at Boston University Field that a lot of people never thought would be done. He kicked a football and thus launched the American Football League's first official game. Discenzo, a 245-pound Boston Patriots' tackle out of Michigan State, would play only one season in the AFL, but with that boot he secured his place in trivia history.

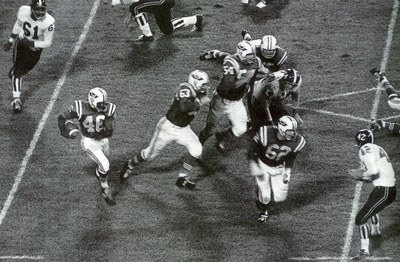

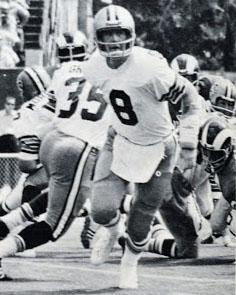

There had been exhibitions going on for nearly six weeks ... so the first official game was only a surprise in relation to the many predictions of the previous spring that the AFL would never get off the ground. By midsummer, with eight teams in training camp, most doomsayers were willing to admit that the new league would, against all odds, play its first season - or at least part of it.  Action from the first AFL regular season game between Boston and Denver. The Broncos' vertical-striped socks lasted only one year. "At the time, I didn't have the luxury of thinking I had made history by scoring the first AFL points ever," Cappelletti explained. "We didn't have much time for history. We were concerned about surviving. I knew that if I messed up that first kick, I might not get a chance to try another one. In the beginning, you never really knew if you had made the team. I had been out of college since 1956. Then I played ball in Ontario for two years. When Bob McNamara mentioned me to Lou Saban, I was working at my brother's bar in Minneapolis, wondering if I'd ever get a chance to play pro football." In that first game, Cappelletti played defensive back - "You couldn't be just a kicker then because the teams carried only 33 players" - but he was slow afoot and Denver took advantage of that. Shortly afterward, he was switched to wide receiver where his soft hands enabled him to catch anything he could reach. By the time he retired 11 seasons later, he had made 292 catches good for 42 touchdowns.     L-R: Bob McNamara, Al Carmichael, Frank Tripucka, Gino Cappelletti Carmichael, a scatback out of USC, spent six seasons with the Green Bay Packers in the pre-Lombardi years, specializing in kick returns. "I saw the AFL as a chance to play more pro football," he said. "I didn't think of it as a step backward to play in the new league. It never mattered to me who was hitting me when I was playing. You felt it just as hard in the AFL as you did in the NFL." Tripucka had been a standout quarterback at Notre Dame in 1948. After four so-so years in the NFL, he headed for Canada where he became a star. At 33, he was ready to forego the aches and bruises so "when they asked me to come to Denver, I thought I would be only a coach. I thought I was through with playing." With that understanding, he signed with the Broncos for $15,000 - $20,000 less than he was making in Canada. Also pressed into surprise service for Denver in that first AFL game was Gene Mingo, the team's placekicker. "I didn't expect to be returning punts that night," he remembers, "but someone had gotten hurt and so the coach asked me to go in and return kicks." In the third quarter, he brought a Boston punt back 76y for a touchdown. "I was so tired I couldn't get the full leg strength I needed for the extra point, and I hit it weak and it went off." It wasn't needed. The Broncos held on to win 13-10. AFL Tales - 2: Made-for-TV League

When the Grass Was Real, Bob Carroll (1993)

Harry Wismer's association with the American Football League as owner of the New York Titans would be, in the long run, unfortunate. Before he left, he became both a drag and an embarrassment. Yet something he did at the beginning paved the way to ultimate success for the league. When doomsayers equated the AFL with the old AAFC, they ignored one crucial new factor - television. Because of his long career in sports broadcasting, Harry chaired the new league's television committee. He succeeded in pushing through a plan to sell the TV rights as a whole instead of letting each team arrange its own deal. The teams then shared the money equally. Obviously, this was a godsend to teams like Oakland and Denver, whose TV rights would have gone for peanuts if sold separately. Just as obviously, the team most hurt by Wismer's plan was Wismer's. No matter what kind of product the Titans put on the field, the TV rights to it in New York City could bring more into the till than those of any other league team.

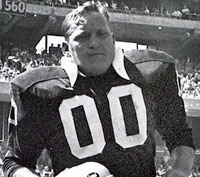

On June 9, ABC announced it was granting the AFL a five-year contract. $1,785,000 would be paid for the first year, and yearly increases would make the average worth $2,125,000 per season over the length of the contract. Split eight ways, the TV money would keep some of the Foolish Club from losing their shirts. Only their cuffs and collars. "That's something the AFL was always prooud of," (Boston owner) Billy Sullivan said, "that we had national TV every Sunday, even when our teams weren't drawing well and people didn't know who we were. And the man most responsible for getting us the national TV contract was Harry Wismer. Without Harry getting us that, there's really no way the AFL could have stayed in business those first few years. He may have had his weaknesses - and he was not a well-liked person - but he did that one thing for the AFL which can never be overlooked."   L-R: Lamar Hunt, Joe Foss (AFL Commissioner), and Harry Wismer; Billy Sullivan For instance, the league had terrible problems in finding places to play. Until 1973, the Buffalo Bills used WPA-built War Memorial Stadium - called "The Rockpile" for its granitelike playing surface - which fans and players hated. Tucked away in the heart of a ghetto, The Pile wasn't the safest place to be. Indeed, a Bills' vice-president was mugged after one game. The stadium had no public parking, and those who drove to the game left their cars in driveways or yards where one paid the owner "$2 to park and $5 to watch your car." Despite the setting, Buffalo was consistently among the AFL leaders in attendance. Reportedly, the Bills' losses in the AFL's first season were the smallest in the league - $175,000. When War Memorial was expanded to seat 45,000 (from 36,000) in 1965, the average attendance went up to 43,811. That was small consolation for the players who had to put up with the shoddy dressing rooms. "If two showerheads worked and you got warm water, you considered yourself fortunate," Bills DE Ron McDole, who joined the team in 1963, said. "It was the worst!" "War Memorial Stadium was one of the worst stadiums in the world," says QB Len Dawson. "I don't know which war had been fought there, but it must have been an old one. I used to get nauseous there. When you went out of the locker room, you stopped in front of an old coffee-and-hot-dog stand to wait for player introductions, and I'll be the coffee grounds had been there since the Civil War. The smell made me sick. And the quarterback was always introduced last."     L-R: Ron McDole, Len Dawson, Lou Saban, Jim Otto "Finally our coach, Lou Saban, gets this idea that we should put poison in the seeds to kill the pigeons. Next day we're at practice and we spend half the time picking dead pigeons off the field. It was a helluva sight." As bad as War Memorial was, at least the Bills had no major competition for the fan's buck during most of the football season. The 1960 Chargers performed in Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, which seated 100,000 for the Rams but was cavenously empty whenever the Chargers were in town. Why go out to see the new guys when the Rams were on the tube? A similar situation applied to Dallas, where the Texans shared the Cotton Bowl with the NFL Cowboys and both looked at mostly empty seats. The Texans outdrew the Cowboys slightly in their first year, but reportedly Clint Murchison's Cowboys lost "only" $700,000 to Lamar Hunt's $1,000,000 on the Texans. This led old H. L. Hunt to remark that at that rate the "boy only has 123 years to go." Lamar Hunt could afford the bill, but his league couldn't afford to lose face in all three of its head-to-head battles with the NFL. In Denver, Mile High Stadium (then known as Bears Stadium) was still a minor league baseball park. In Houston, the Oilers, who'd hoped to play in Rice University Stadium, were forced instead into Jeppesen Stadium, a high school field. The league lost a lot of face when it played its championship game there. "Once we chased Seagulls off the field," Raider C Jim Otto recalls, "the rain and humidity made the stench pretty bad." The Raiders couldn't even play in Oakland in 1960 and had to settle for decrepit Kezar Stadium across the Bay in San Francisco. The Titans had perhaps the worst deal. While they waited around for Shea Stadium to be built - expected in 1962, delivered in 1964 - they were stuck in the drafty, dirty, dreary Polo Grounds, a monstrosity the baseball Giants had abandoned in 1957 to head west. (Jim Otto: "When they turned on the lights, the drunks woke up.") No one in his right mind wanted to be in the Polo Grounds, especially for a night game, when it was positively scary. New York football fans proved to be mostly in their right minds, although Harry Wismer regularly announced attendances in excess of 20,000. These became known as "Wismer attendances," crowds in which two-thirds of the people came, in the words of sportswriter Dick Young, "disguised as empty seats."   L: War Memorial Stadium; R: Chargers vs Oilers in LA Coliseum   L: Jeppesen Stadium; R: Polo Grounds "Too Small"

"The Trojan Ten: The 10 Thrilling Victories That Changed the Course of USC Football History," Barry LeBrock (2006)

It is not far geographically from East Los Angeles to Westwood, but in so many ways, the two cities are worlds apart. Growing up in the fifties, an East Los Angeles kid named Mike Garrett was a hard-core UCLA football fan who watched hs heroes play on Saturday afternoons.

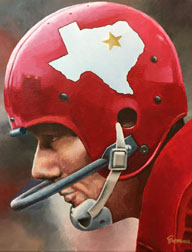

While the Bruins were stringing together three straight top-five finishes, Garrett was having some early success of his own on the athletic fields of his community. When he entered Roosevelt High School in the early sixties, a sports star began to take shape, and his college of choice began to take note. In his junior year, UCLA was first in contact and then in close contact. The interest was unmistakable. And then it was gone. "UCLA recruited me really hard my eleventh grade year, and then they just went cold on me," he says, looking back with nearly half a century of retrospect. "Many years later, one of the UCLA guys told me that they had backed off because they thought I was too small." Not all schools were about to make the same mistake. USC's new coach, John McKay, felt strongly that there was enough talent in Southern California alone that he could put together a winning team made up mostly of local players. His focus turned to Roosevelt High and the blossoming 5'9" prep all-American. "McKay and USC always recruited late," Garrett remembers. "My senior year in high school, they came in and said, 'We want you,' and I said, 'OK. Let's do it.'" And just like that, colors changed, allegiances shifted and USC secured a spectacular superstar in the making who would lead them to new levels of greatness. A member of the 1962 freshman team, Garrett caught wind of the troubles McKay had during the new coach's first two seasons at USC, and very early on, Garrett understood what lay ahead. one day, early in spring practice, McKay wanted there to be no misunderstanding. Garrett explains, "He had the entire team together and said, 'You sons of bitches are not gonna get fired.'" Some players were taken aback, but not the bright-eyed freshman. He says, "You have no idea how hard we worked. And that made our history. McKay made modern USC football. We always felt everything on the field. I loved John McKay. I just loved him. He was the first guy I ever met that matched my tenacity in gettin' after it. McKay was a tough guy. Our workouts were very much like Pete Carroll's. We scrimmaged so much. That's when we had 120 guys. Man, it was a meat grinder. If you were faint of heart or you couldn't play with pain or soreness, you couldn't play here."    L-R: Mike Garrett with USC, John McKay, Garrett with Kansas City Chiefs Anybody who ever played with him, or even saw him play, speaks glowingly of Mike Garrett's talent. OJ Simpson: "He was almost kinetic in the way he moved, in his ability to juke guys." Marcus Allen: "Total scat-back. Moves, speed, strength - the guy had everything." Anthony Davis: "He was the forefather of the great runners at USC." Rod Sherman: "He had tremendous balance and tremendous explosion. He also had an enormous amount of enthusiasm. He approached every day in practice like it was game day." Craig Fertig: "He owes all of his success to me." Fertig, of course, is known for his sense of humor, and he points out that the only way for a running back to get the ball is for a quarterback to either hand it to him or throw it to him. By that logic, though, Fertig owes all of his success to the centers he played with throughout his career. A bit more seriously, Fertig says, "If I was in a street fight and I could have one guy on my side, I'm takin' Mike Garrett." Steve Brady, a tailback at USC in 1966 and 1967, says that Garrett is "the shiftiest runner I have ever seen in football. He could fake you out in a hallway." As USC returned for the 1963 season as national champions and Rose Bowl winners, Mike Garrett was a sophomore determined to play a large role in the Trojans' success in the years ahead, and he got off to a great start. The 1963 Trojans went 7-3, with Garrett establishing himself as an offensive force. He ran for 833y, averaging a whopping 6.5ypc. The following year was even more impressive as the slippery tailback started to garner national recognition as one of the best runners in the country. Garrett's rushing total increased to 948y, and he was heavily relied on as USC made a run at another Rose Bowl. Color Them Spartan

The Biggest Game of Them All: Notre Dame, Michigan State, and the Fall of '66

Mike Celizic (1992) Michigan State had roared through 1965, literally annihilating a tough Big Ten schedule, allowing fewer than 50 yards rushing per game. They had wiped out Notre Dame and Penn State, had beaten UCLA, and had gone to the Rose Bowl. But at the Rose Bowl they had lost to UCLA in their second meeting of that season. The loss cost them number one in the AP poll, which held up its final vote until the top contenders from the National Championship - Michigan State and Alabama - played their bowl games. They captured UPI's top ranking, taken after the end of the regular season, but the loss to UCLA ... left a bitter aftertaste to a spectacular season.

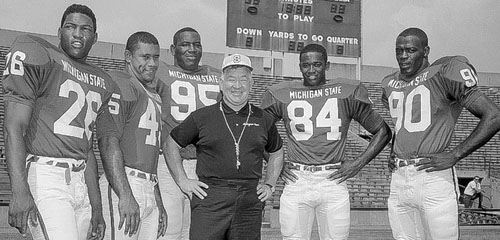

Most of the stars of 1965 were back. George Webster, Charlie Thornhill, and Bubba Smith headed the defense, and HB Clinton Jones, FB Bob Apisa, and E Gene Washington had returned on offense. These were franchise players, and there was enough behind them to form a team that could claim to be one of the best ever. They knew it, and their goal was to fulfill that claim. ... You could call them arrogant, and they were that, but it was the arrogance of great athletes who knew their own ability. Underlying that arrogance was a rare sense of team unity. Like Notre Dame, the Spartans had great coaching and great personnel, but other teams had had as much without reaching the same heights. It was the sense of family, of being in it not as individuals but as a team, that pushed them to another level. That and the sting of the lone defeat of 1965. ... Notre Dame had always laid claim to a national recruiting program, but Michigan State coach Duffy Daugherty had made the Irish look positively parochial. He had scoured the country from top to bottom and shore to shore and beyond to assemble his team. When he was done, he had three Hawaiians, including a barefoot kicker, Dick Kenney. He had a black quarterback. He had eight blacks - most of them from the South, which was still practically a foreign country - starting on defense. Blacks had been playing college football for a long time, but seldom in such numbers and seldom in such key positions. Both of Daugherty's captains, Webster on defense and Jones on offense, were black. A lot of people thought white players couldn't or wouldn't perform under black leadership. The same people thought you couldn't win with a black majority. Surely blacks and whites couldn't get along, couldn't find common ground, even on the field of play. But Michigan State took all of that as added incentive. They'd prove those ideas wrong. ...  L-R: Clint Jones, Bob Apisa, Bubba Smith, Duffy Daugherty, Gene Washington, George Webster In 1950 the National Football League began allowing free substitutions, and two-platoon football began. The NCAA, however, accepted the system only grudgingly and only over a long period of time. ... Gradually, the substitution rules were liberalized. By 1963 it was possible to substitute entire units, but the changes had to be made piecemeal, a limited number of men at a time. ... After that season ... college substitution restrictions finally were dropped entirely. The era of specialization had begun in earnest.

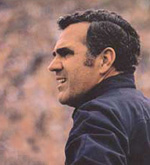

When Ara Parseghian went to Notre Dame in 1964, part of his stunning success could be traced directly to his ability to take advantage of the new rules. ... He put his best all-around athletes on defense and his best skill players ... on offense. Big, fast players went to the defensive line. Big, slower players to the offensive line. His talent was in being able to identify a player's best position. The result was a 9-1 season and instant celebrity status for Parseghian. Duffy Daugherty didn't catch on quite as quickly. Enamored with offensive football, he didn't give his defense the players it needed to succeed. He also didn't fully use all his players. George Webster, for instance, alternated between offensive and defensive end in 1964, his first varsity season. But because he alternated with Bubba Smith at defensive end, both were seldom in the game at the same time. Meanwhile, Charlie Thornhill, who would become a demon at linebacker, was playing in the offensive backfield, the same position S Jess Phillips first played when he arrived on campus in 1964. When Daugherty brought in his 1963 freshman class and introduced them to one another, many of them wondered, "What am I doing here?" Even Bubba was in awe as the coaches introduced the players to one another. It seemed that every person in the room was a high school All-American or All State at the least. Smith, who had played anonymously in a black conference, wasn't all anything. One of his high school coaches had told him that when he got to college there would be other big men to compete with. "You might not make it," the coach said. "I don't care what you or anybody else says, I'm going to make it," Bubba told him. But now, in this room surrounded by prime beef, Bubba Smith, the human mountain range, had doubts. Maybe the coach had been right. He turned to George Webster ... and said, "Goddamn, George, all these guys are All-Americans." And Webster replied, "Screw it." "Yeah," Bubba said, the bravado swelling in him, "screw it."    L-R: Ara Parseghian, Charlie Thornhill, Jess Phillips If they were, it didn't show right away. When they became sophomores in 1964 and eligible to play, they looked good on paper but not on the field as they stumbled through a 4-5 season. Before the season ended, stuffed Duffy dummies were being strung up on campus ... One of the few positive things that happened in that forgettable year was the emergence of Charlie Thornhill as a linebacker. ... From Roanoke VA, Thornhill was one of the greatest high school running backs Virginia had ever seen. He led his team to three straight league titles and scored 219 points in his high school career. He was so good that even though he went to an all-black high school, the local white citizenry flocked to his games to watch him perform. ... Thornhill was good enough to attract the attention of Notre Dame ... He wasn't impressed with the 10 P.M. lights-out rule or the fact that there weren't any women at school, but he was on the verge of going there anyway when Paul "Bear" Bryant intervened. ... Bryant couldn't recruit blacks because the University of Alabama was still busy fighting the Civil War, but he could scout them and tell his friends about them. One of his good friends was Duffy Daugherty. As luck would have it, several years earlier Daugherty had been slavering over a hot young quarterback out of Beaver Falls PA by the name of Joe Namath. Daugherty recruited him heavily and dearly wanted him to run the Spartan offense, but ... he couldn't get Namath's high school transcript past the Michigan State admissions office. Unable to take Namath himself, he told Bryant about him. Alabama's lofty admissions requirements, which had no place for blacks, proved no obstacle for Namath, who helped the Crimson Tide to a National Championship in 1964, his senior season. When Bryant saw Thornhill, he thought of Daugherty and the favor he owed him. At a Virginia awards banquet, Bryant sought out Thornhill and told him that before he committed to Notre Dame he would do well to listen to Duffy Daugherty at Michigan State. Thornhill visited the campus and liked it. He especially appreciated the fact that Michigan State allowed women to enroll and didn't make its students turn the lights out at ten. Tumultuous Times

Football Nation: Four Hundred Years of America's Game from the Library of Congress,

Susan Reyburn (2013) The 1969 season marked a turning point for many black athletes, who had, the previous summer, witnessed U.S. Olympians John Carlos and Tommie Smith raise gloved fists at their medal ceremony in Mexico City as a sign of black power. Amid the unraveling of tightly wound cultural values and widespread student unrest, black athletes actiely expressed long-held grievances regarding unequal treatment, hostile locker room environments, and programs whose interest in them expired when their playing eligibility ended. Reacting to a heretofore-unknown type of player was a coach for whom the term "old school" was devised and who was flummoxed by the more freewheeling young men (white and black) who graced his roster and irritated his ulcers. The culture clash between that fraternity of coaches and their charges was even greater when it came to racial matters, and it was why so many players began asking that their teams hire black assistant coaches, who better understood them. Of the many racial collisions affecting teams nationwide, perhaps the least expected occurred in Laramie, Wyoming, a year after the Cowboys made their first appearance in the Sugar Bowl. Midway through the 1969 season, Wyoming coach Lloyd Eaton, who prohibited players from taking part in student demonstrations of any kind, summarily dismissed all fourteen black players from the squad for wearing black armbands the day before their game against Brigham Young University. The men were protesting the Mormon Church, which owned and operated BYU, for its policy that excluded black males from the priesthood (a policy that was revoked in 1978). "The demonstrations are not against BYU because it doesn't have any black players - but because it is sponsored by the Mormon Church," said Willie Hysaw, one of the Wyoming Fourteen.    L-R: Lloyd Eaton, Harry Edwards, Sam Cunningham The coach's analysis was actually in sync with arguments sociologist Harry Edwards, author of The Revolt of the Black Athlete (1969) and orchestrator of the Olympic protest, was making in his condemnation of standard practices in collegiate athletics. Not only were many of these players brought into completely foreign environments and given little useful guidance, but, wrote Edwards, "lofty academic goals might jeopardize a black athlete's college career and thus wipe out the college's financial investment in him." Scandalous reports in the 1970s, revealing the extent to which so many college athletes - especially blacks, but whites as well - were shepherded through meaningless coursework illustrated the devastating effects of what had once been jokes about jock classes and low expectations. Athletes were completing four years of player eligibility with little progress toward a degree and, in deeply embarrassing cases to both athletes and schools, with the same level of illiteracy they had the day they arrived. Meanwhile, throughout the 1960s, desegregation lurched along in public schools throughout the country. It reached the farthest recesses of the Deep South in the early 1970s. At the University of Alabama, which had black students but no varsity gridders, Southern football's Lost Cause succumbed to the times and to the USC Trojans. Much has been made of the role Trojan TB Sam "Bam" Cunningham had on Alabama's decision to recruit black players, after he ran roughshod over the Tide in front of their fans, leading USC to a decisive victory in the first game of the 1970 season. (Said Virginia Tech coach Jerry Claiborne: "Sam Cunningham did more for integration in sixty minutes than Martin Luther King did in twenty years.") Yet Alabama coach Paul "Bear" Bryant, who bristled at the notion that he was responsible for his team's monochrome appearance, had a black freshman in the pipeline and had, he said, invested "$100,000 ... recruiting Negro players all over the country." Considering local history, it was clear why blacks were not swarming to join the program. Although the revered coach was frequently mentioned as a gubernatorial candidate, not even the influential Bryant could sway the state's powers-that-be to sign black players until the need arose and legal recourse ceased. "You must remember, these were dangerous times, fearful times," Frank A. Rose, the university president, told Howell Raines, an Alabama native then reporting for the New York Times, shortly after Bryant died in 1983. Even before the USC game, Rose and Bryant preferred to quietly urge alumni and business groups to accept integration rather than publicly call for it. Within fifteen years of the Bear's death, the significance of integration's effect on football was most evident, and the majority of Southeastern Conference players were black. What a Way to Start Your NFL Career

Archie Manning (as told to Chuck O'Donnell), The Football Game I'll Never Forget:

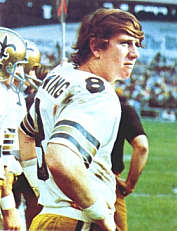

100 NFL Stars' Stories as selected by Chris McDonnell(2004) September 19, 1971

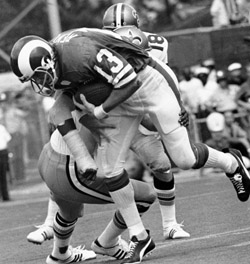

I was laying in the end zone after diving across the goal line with three seconds remaining in my first NFL game, in 1971 with New Orleans. My one-yard scamper around the left end had capped a dramatic last-minute march down the field, giving us a 24-20 victory over the Los Angeles Rams. Maybe this win would send us toward a Cinderella season. Maybe I would be carried off the field by my teammates. Maybe this was a defining moment for me and the team. Or maybe not. Lying there, I happened to notice a few referees, talking about the play. As they were discussing whether I had had possession and scored - or whether it was a fumble and we were about to lose - I thought to myself, "You can't take this moment away from us. Please don't take the touchdown away from us." We had worked too hard and come too far to lose like this. I joined the Saints that season when they made me the second pick overall in the draft. During the offseason, the Saints had traded veteran QB Billy Kilmer to make room for me to take over the starting job. Coming from the Bayou - being drafted out of Ole Miss - I naturally was viewed as the hometown boy who would be a savior of sorts. The Saints hadn't had a winning season in their first four years of existence, and I was supposed to change all that.    Archie Manning hands to Bob Gresham and passes against the Rams in 1971. While we may have been short on experience, we had plenty of enthusiasm. We were upbeat entering the 1971 season opener against the Rams. They were one of the best teams in the league during that period, led by Roman Gabriel, who was a smart, strong-armed quarterback. Whether he was handing off to 1,000-yard rusher Willie Ellison or throwing to Lance Rentzel or Jack Snow, Gabriel was a superb field general. The Rams defense was downright scary. On the front line, the team had Deacon Jones, Merlin Olsen and Coy Bacon starting with a young guy named Jack Youngblood - who eventually became an All-Pro himself - coming in to spell them. As if it weren't bad enough having those guys breathing down your neck, it was an oppressively hot day in New Orleans for that season opener. The teams traded field goals in the second quarter, but we broke out on top in the third quarter. I hit TE Dave Parks with a 6-yard touchdown pass, then Gresham added a 2-yard touchdown run.   L: Roman Gabriel vs Saints; R: Bob Pollard (82) tackles a Ram. Doubt could have easily seeped in, but we just went out there determined to win the game. Starting at our 30 on our final drive, we methodically moved down the field. Mixing mostly passes with a few runs to keep the Rams honest, we got the ball down to the one-yard line. There was enough time left for just one more play. We called a play where I would roll out to my left and would have the option of throwing the ball or tucking it under my arm and running into the end zone. As I took the ball from center and began to roll, I saw an opening. I told myself that I couldn't throw it - I had to run it. I put my head down and bowled into the end zone, with the ball coming loose at one point. Was it a touchdown or a fumble? I sat and waited for the call for what seemed like an eternity. When the refs raised their hands into the air to signify a touchdown, it set off a celebration. Our players went wild. We had stolen a 24-20 victory from the mighty Rams. So, was it really a touchdown? Did I fumble before I crossed the goal line? I honestly don't know - and looking back, I don't really care. The Snowplow Game Don Shula: A Biography of the Winningest Coach in NFL History, Carlo DeVito (2018)

After a players strike canceled eight weeks of the 1982 NFL season, the 4-1 Miami Dolphins met the 2-3 New England Patriots on December 12 at Schaefer Stadium in Foxboro MA.

The Dolphins and Patriots played to a scoreless tie going into the fourth quarter on a frozen field ... There had been ice and snow, and only the yard lines had been plowed the snow was so thick. Both teams slipped and slid throughout the game, finding no traction on the covered field. Miami DE Kim Bokamper recalled, "I woke up that morning and looked out the window and just saw snow everywhere. I could see it was going to be that kind of day. It was always tough for us to play up in New England, but during the game the snow was on the field nonstop." Bokamper remembered that during any break in the action the field crew would plow the yard lines "just so you could see where you were out on the field." The crew worked feverishly throughout the game. "There were two field goal attempts in the game and neither was made. The kickers couldn't get any footing because under the snow there was ice." The Patriots had struggled into Dolphins territory with 4:45 left in the game. Patriots head coach Ron Meyer signaled for his kicker, John Smith, to attempt a 33-yard field goal. But before he did, Meyer suddenly turned to a man sitting on a John Deere tractor and motioned to him. "Get out there and do something," yelled Meyer. "I knew exactly what he meant," said operator Mark Henderson. Henderson was a convicted burglar on work-release who volunteered to operate the field equipment. He had come directly from the MCI-Norfolk prison. "I remember standing on the field, and they were going to attempt another field goal, and I see the snowplow going on the field," said Bokamper. "I didn't think anything of it because he had been clearing the yard lines and it was a stop in play. He got about 10 or 15 feet away from me, then he veered back on to the field and went right to where the kicker was and he cleared out a patch for him.   "Matt Cavanaugh was already getting down on one knee to hold for John Smith's field-goal attempt. This part of the story is very misconstrued," recalled Hall of Fame Patriots offensive tackle John Hannah. "In reality, the tractor had not swept the exact spot where the ball was going to be placed. Instead the drive had actually thrown a whole bunch more loose snow over the spot Cav had cleared. So Cav and Smith had to quickly get down and sweep the spot clear with their hands again just in the nick of time." ... Bokamper: "Coach Shula started yelling from the sideline. He was just livid. The one thing about Coach Shula is that we were always the least-penalized team in the league. He believed in the letter of the law. If it wasn't legal, he wasn't going to do it. Even if he could gain an advantage, he wasn't going to do it. So anytime anyone circumvented the rules, he just went livid. He was beside himself on the sideline throughout the whole thing." "I could see the Dolphins sideline explode on the opposite side of the field, and instantly Shula was leading a charge of assistant coaches and players toward the middle of the field. They were all yelling and screaming, throwing playbooks, headsets, and helmets," remembered Hannah. "After what seemed like an eternity of argument, protests, screaming, and hollering, the game resumed, and the play stood." "I think it's the most unfair thing that I've ever been associated with in coaching. It's the most unsportsmanlike act that I've ever been around," said Shula. "I was bewildered ... about what was happening out there on the field in front of my eyes. The magnitude of it never really set in until after he had lined up to kick the field goal." "We got a chance to tie the game at the other end. No snowplow. Our kicker slips and falls on his butt," chuckled Shula years later. The Patriots won, 3-0. "It's the first time since I've been in professional football we've ever taken such serious exception to something which happened on the field," said an incensed Joe Robbie, the Dolphins owner. "That kind of thing should not occur as a result of somebody putting a snowplow run by a convict with a day off from prison, out on to the field to give special advantage to the home team." "I'm sure if you were the other coach on the other sideline, you would say it would be a black mark," said Patriots Coach Ron Meyer. "But I know one thing: I can live with myself on it, and it wasn't an attempt to deceiver or it wasn't an attempt to cheat anybody." ... Shula continued to protest to NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle. Rozelle agreed but could do nothing about it after the fact. Not surprisingly, the NFL Competition Committee banned the use of snowplows on the field during a game. ... Said Bokamper years later: "It's funny. The Dolphins played up there many years later when they were closing the stadium before they moved into Gillette Stadium. They had a ceremony where they brought back some of the legends who had played there like Russ Francis and Steve Grogan. I'll never forget who got the loudest ovation. It was Mark Henderson." The John Deere Model 314 tractor, complete with sweeper attached, was commemorated at the Hall at Patriot Place at the new Gillette Stadium, where it hung from the ceiling.Watch a video of the winning kick ... Controlled Chaos - 1

Greg Bishop, Sports Illustrated (August 15, 2020)

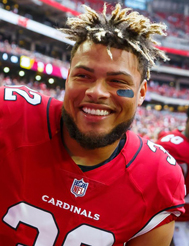

A nomadic star, Tyrann Mathieu, became the missing piece in the Chiefs' Super Bowl puzzle. And amid the turbulence of a pandemic and social upheaval, he emerged as one of the most prominent voices among athlete activists. Tyrann Mathieu looked up, past the red-and-gold confetti falling from the sky, and saw only stars, like the whole galaxy had been lit. He could hardly speak. He couldn't move. The screaming fans, the euphoric teammates, the thuds of bass coming from the speakers - it all faded into a dreamlike silence. Mathieu asked himself a question he already knew the answer to: How in the world did I end up here?

On the night the Chiefs secured their first Super Bowl berth in half a century last January, he climbed atop a stage that had been wheeled onto the Arrowhead Stadium turf. He watched the family of late team founder Lamar Hunt accept the trophy that bears his name. The packed crowd stuck around through the freezing temperatures, the diehards dancing and crying. Mathieu spotted Brett Veach. The GM had signed him before the season and promised that the free-agent safety would elevate Kansas City after years of missteps and heartbreak (for both franchise and player) back to the pinnacle. Then Mathieu flashed back to absolute bottom. The funerals, the failed drug tests, the injuries. Had he really considered retirement? He drifted back, remembering how eventually he found himself, and then his chi, and then his voice, with help from a spiritual adviser, a naturopathic doctor and a mindfulness coach. ... The stars had aligned around the safety, but Mathieu did not feel bliss, nerves or even accomplishment. Instead, he felt balance, peace. Through discomfort, he had discovered something unexpected: his own brand of Zen. Today's Tyrann Mathieu can hardly recognize previous iterations of himself. But to arrive here, as a cornerstone of a Super Bowl champion and a prominent voice for social justice, he had to first examine everything that went wrong. Only then could he make everything right.    Sure, Mathieu could run, jump, tackle and defend. And he did all that, mostly by channeling the rage that surged like electricity inside him. He could drop into an LSU football camp, ignore the chaos that spun his life in every direction and show coach Les Miles that he deserved a scholarship, even at 5'9". Miles could tell, though, that the young man looked upon himself through a fun-house mirror, his perception warped. Mathieu saw a singularly-focused athlete who didn't deserve to be happy, and who didn't love himself, making it hard for him to love anybody else. In Baton Rouge, Miles noticed those same flickers as Collins once had, only they were happening more often and more intensely, as Mathieu flipped between who he was and what he wanted to become. Mathieu was one of the most versatile players Miles ever coached. On the field, he returned punts, intercepted passes, jumped over blockers, patrolled the secondary, sacked quarterbacks and forced fumbles. He claimed the Chuck Bednarik Award as the nation's top defender in 2011 and that fall earned a rare invitation for a defender to the Heisman ceremony. With his distinctive blond hair and unforgettable Honey Badger nickname, Mathieu - a defensive back - became the most recognizable player in college football. The following August, though, Miles kicked Mathieu off the team. He'd failed too many drug tests - at least 10, according to media reports - and broken too many rules. "It was the hardest thing I ever had to do," the coach says. Mathieu was never late, never lazy, never a distraction on the field - he just couldn't stay out of trouble off of it. When Miles booted him, he stayed silent. He knew. In the 2013 NFL draft, Mathieu plummeted all the way to the third round, to Arizona . He tore his left ACL that rookie season, busted a thumb in Year 2, tore his other ACL in Year 3 and separated his right shoulder in Year 4. Four seasons, four injuries, 16 games missed (including playoffs). He started to doubt himself more deeply; the feeling bolstered when the Cardinals drafted his replacement and then cut Mathieu following the 2017 season. The Texans signed him for cheap and discarded him after one year. At times he wondered whether football was really for him; he considered what a different life might look like. He questioned whether anybody really loved him and, he admits, sabotaged much of the support he got. "Most people would say I'm too good to be on my third team," he says. That's true. And yet, there he was. For years, Mathieu wondered why he always had to take - or had always taken - the hardest route. Breaks never seemed to fall his way. Why did he hold onto (or pick at) so many wounds? Continued below ...

Controlled Chaos - 2

Greg Bishop, Sports Illustrated (August 15, 2020)

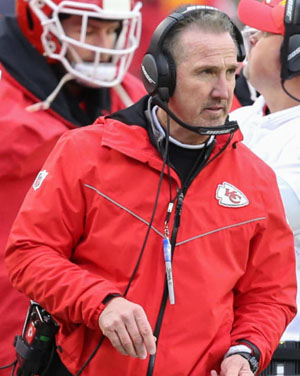

Mathieu cannot pinpoint his exact low point. The nadir didn't result from checking into rehab for marijuana use in 2012. Or when he spent a night in jail on a marijuana charge and had his cellmates tell him to look around, that he didn't belong there. Or when he showed up at McNeese State later that year, hoping to transfer, dressed to display disengagement: a stained tank top and shorts. Each time, he told himself the same thing. Something's gotta change. I can't live like this anymore. I'm wasting my potential. Even then, he never could sustain progress. There were always fits and starts. Looking back, Mathieu says no one had ever taught him how to process his emotions. Or build and sustain healthy relationships. Or express empathy and gratitude. Upon his arrival in Arizona, in 2013, he sought guidance, trying to take control of his life away from football, hoping that might correct his path. He met Donny Starkins, a mindfulness coach and yogi who had worked with other pro athletes, and said, "I've been looking for somebody like you." ... Donny tried to disabuse Mathieu of the notion that football alone made him worthwhile and helped him to focus, eliminate distractions, breathe. "Happiness," he said, "is an inside job." Progress wasn't linear. Mathieu earned first-team All-Pro with the Cardinals in 2015. He dropped the Honey Badger nickname and started most mornings with meditation sessions outside in the desert sun. But the injuries exacted a new psychological toll. Lee-Collins visited after the second ACL tear and says, "I saw how it was weighing on him. He was doing everything right, and then - Bam!" Mathieu went to therapy and drew praise from Cardinals coaches for his leadership. He became vulnerable in ways teammates never could have expected, sharing his story and his path - and how he took back control. He became a walking self-help book, its dust jacket covered in scars. ... He began to see himself in different mirrors. As a present father of three children. As a stable, positive force. He still screwed up, but the tools he was learning kept his emotions largely in check, including when he was released or passed over. After the Texans chose not to re-sign him following the 2018 season, he thanked coach Bill O'Brien for what he'd learned, for the ways O'Brien had pushed him to lead. In Houston he had been named captain in a matter of months, becoming a stable force and positive impact.    L-R: Tyrann Mathieu with Houston, Steve Spanuolo, Mathieu vs Houston in playoffs In Kansas City, Mathieu and Spags bonded immediately. Perhaps that started with flattery. The coach told his new safety that he evoked Brian Dawkins, the Hall of Famer he oversaw in Philadelphia. He said, "You're the guy I always wanted to coach," and promised he wouldn't move Mathieu all over the field, like others had. He wanted Mathieu to play free safety - to roam on instinct, blitzing regularly. His coordinator's belief meant everything to Mathieu. His belief in himself meant even more. He fit well in Kansas City - a homebody who loved football and barbecue and carried an ethos of everyman toughness. City, team and fan base loved him back; they'd seen elite defenders in recent seasons, but never one like Mathieu, who claims, "I do things no other safety does." He would tip the Chiefs over the edge, one way or another. For a while, though, the franchise's 2019 season took a turn toward mediocrity. Injuries piled up, with Mahomes playing through a bum ankle early and later missing two games after dislocating his kneecap. When slot corner Kendall Fuller joined the QB in the training room with a busted thumb in Week 6, Spagnuolo had to undo his promise, moving Mathieu all over the field, like the queen on a defensive chessboard. Mathieu can pinpoint the exact weekend the season was saved. The Chiefs were 6-4 in mid-November, headed to Mexico City to play the Chargers. The safety believed his teammates were making too many excuses, starting with Mahomes's injuries, but they were also banking on the eventual coalescence of a revamped defensive unit. Finally, he and Spags addressed the group. The time had come, they said, to eliminate all the explanations and justifications. Just play ball. The Chiefs turned inward, like their safety. They topped the Chargers, healed up over the Week 12 bye and never lost again. Mahomes rounded back into MVP form, and the defense, led by Mathieu, DT Chris Jones, and edge rusher Frank Clark, sparked a late-season surge. A unit that ranked 31st in total defense in 2018 was suddenly among the most feared in the league, allowing an average of 11.7 points over the last seven weeks, sometimes winning with stout D rather than typically prolific Mahomes performances. ... For the first time since 2015, Mathieu was named All-Pro, but his impact stretched beyond anything measured by stats or awards. Down 24-0 to the Texans in the divisional round, he ran up and down the KC sideline, imploring teammates to look across the field. "You should've seen them," he says of his old Houston teammates. "Pompoms, popcorn. ... They thought the game was over, man. I wanted my teammates to smell that blood." Of course, he had been up when the team was down, thriving in discomfort yet again. One week later the Chiefs came back and toppled the Titans. Mathieu zoned out afterward onstage. "You have to see the moment," he says months later, echoing his mindfulness coach, "in order to really seize it." To be continued ...

End Game

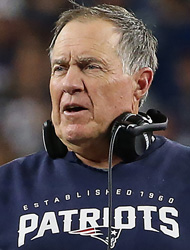

The Dynasty, Jeff Benedict (2020)

Heading into the 2019 season, Bill Belichick was focused on one thing—winning the next championship. He liked his team's chances. The roster was rich with mentally and physically tough guys who understood what it took to win. But Belichick, who was now 67, never stopped looking for players who could make the Patriots better. And on Saturday, September 6, 2019, he saw one who immediately piqued his interest. That morning, Oakland Raiders wide receiver Antonio Brown went on Instagram and called on the team to release him from his contract. Within hours, the Raiders obliged. And by 11:00 a.m., the league confirmed that Brown would be eligible to sign with another team at four that afternoon. Belichick immediately started working the phones to gather information. Brown was considered the most talented wide receiver in the league. For six consecutive seasons in Pittsburgh, he caught more than 100 passes and racked up more than 1,200 receiving yards, making him the most prolific receiver in Steelers history. But by the end of the 2018 season, he was openly feuding with QB Ben Roethlisberger and had become such a disruptive presence in the locker room that the team traded him to Oakland in 2019. After the Raiders offered Brown a three-year contract worth $54 million, he announced he'd be a "good force" in Oakland. Then he showed up for the first day of training camp in a hot-air balloon. Things went downhill from there. He started missing practices. He got into a feud with the league over his desire to wear a helmet that had been banned for safety reasons. The team fined him multiple times over absences. Eventually, things devolved to the point that Brown got into an altercation with the team's general manager, prompting the Raiders to suspend him for the season opener. That's when Raiders took to social media, saying he wanted out of his $ 54 million contract. Belichick recognized that Brown had a mercurial personality. In the space of one summer he'd worn out his welcome with two franchises. But the Patriots' biggest weakness heading into 2019 was its receiving corps. Brady's favorite target, TE Rob Gronkowski, had retired in the offseason. And although they still had Julian Edelman, there were a lot of question marks beneath him on the depth chart. The addition of Brown would be a game changer that could make the Patriots' offense all but unstoppable. Normally, Belichick had full autonomy to make player personnel decisions. But in certain instances he knew he needed the owner's blessing. Signing the most controversial player in the NFL certainly fit that category. Belichick reached for his phone. Although it was a Saturday and the Patriots front office was closed, 78-year-old Robert Kraft was at his desk. With just over 24 hours until the home opener, he was catching up on correspondence and making phone calls. ... The moment that the Raiders cut Brown, Kraft expected he'd get a call from Belichick. After being together for so long, he knew how Belichick rolled. ... Belichick cut to the chase. He thought he could sign Brown to a one-year contract. It would cost $ 15 million—a $ 10 million signing bonus and $5 million in base salary. But if he was going to do it, he had to act fast. Other teams were in the hunt. "He obviously would help us a lot," Belichick told Kraft. Kraft brought up Brown's erratic behavior. "I don't think he's really that bad to deal with," Belichick said. "Look, he hasn't worked out much in the preseason. But he would help us. Believe me." "Do you know him?" Kraft said. "I don't have any direct relationship," Belichick said. "So that's the risk," Kraft said. "I'm not really worried about that," Belichick said. "I believe he had a domestic-violence accusation in the past," Kraft said. "How did that play out?" "He's a pretty good kid," Belichick said. "Doesn't drink. Doesn't smoke. I'm not aware of any domestic violence." Belichick had another call coming in. It was from Raiders general manager Mike Mayock. "Let me take this," he told Kraft. "I'll call you back."     L-R: Bill Belichick, Antonio Brown, Robert Kraft, Tom Brady Brady was home watching the Michigan-Army football game. He turned down the volume when he saw Kraft's name on his caller ID. He listened intently as Kraft told him that he and Belichick were considering signing Antonio Brown. "What do you think?" Kraft said. Brady appreciated being asked. One of his biggest frustrations in recent years had been the way key personnel decisions that affected the offense were made without input from him. A week earlier, Belichick had cut backup quarterback Brian Hoyer and veteran receiver Demaryius Thomas. Brady had great chemistry with Hoyer, who was thirty-three and had a wife and kids. Brady considered him an important asset to the offense. And with the Patriots lacking depth at wide receiver, Brady would have preferred to keep an experienced receiver like Thomas on the roster as well. It aggravated him that after two decades as the team's quarterback, he still wasn't a part of the conversation before important moves were made. So he appreciated the fact that Kraft was seeking his input on whether to sign Antonio Brown. "I'm all for it," he told Kraft. "One hundred percent." "So you support it one hundred percent?" Kraft said. "A thousand percent!" Brady said. The last time he had a wide receiver with Brown's talent was when Belichick traded to get Randy Moss in 2007. That year, Brady set an NFL record for touchdown passes and Moss set an NFL record for touchdown receptions. For Brady, the prospect of throwing to Brown gave him something to look forward to. "Well, you deserve it," Kraft said. Brady was so thrilled that he couldn't wait to get on the practice field with Brown. "All right," Kraft said. "Here we go. I love you." ... Minutes later, Belichick called Kraft back. He had talked to the Raiders. The Patriots, he assured Kraft, were free to strike the deal with Brown. "Are you prepared to do it?" Kraft said. "Yeah," Belichick said. Kraft hesitated. He was still uneasy about signing Brown. But he desperately wanted to keep Brady in New England beyond 2019. And the clock was ticking. "Make the deal," he told Belichick. The next day, Antonio Brown arrived in New England, a sixth Super Bowl banner was raised at Gillette Stadium, and the Patriots blew out the Steelers to start the season. But things went sideways with Brown ... The season— the twentieth that Kraft, Belichick, and Brady spent together— was filled with frustration. Six weeks after it ended, the quarterback of the greatest sports dynasty of the 21st century left the Patriots and joined the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. The departure of the most revered athlete in Boston's storied history marked the end of a golden era the likes of which the football world has never witnessed. |