|

The National Forgotten League, Dan Daly (2012)

The kickoff of the 1937 title game between the Bears and Redskins at Wrigley Field was moved up from 2:00 p.m. to 1:15 - and for good reason, too. The week before, the Bears' regular-season finale against the [Chicago] Cardinals at Comiskey Park had ended in total darkness ... and near-total chaos.

What kind of chaos? Well, in the fourth quarter the Bears scored a safety when a snap went whizzing past the Cardinals' punter and out of the end zone. He never saw the ball. The Cards then answered with a 97y shovel pass to Gus Tinsley [LSU] that caught the Bears completely unawares. (It's kind of the football equivalent of Gabby Hartnett's Homer in the Gloamin' for the Cubs in '38. In fact, at the time, it was the longest touchdown pass in NFL history.) Tinsley "ran up the sidelines," George Strickler wrote in the Chicago Tribune, "and was at midfield before the Bears realized anyone was loose. Even then they had their doubts, for all that was visible of the runner in the darkness was a pair of silver pants. Some Bear hero, whose identity was hidden by the night, then realized pants seldom go running around without a sponsor and gave futile chase." As Tinsley sprinted toward the goal line, the crowd swarmed the field, forcing the officials to call the game with the Bears on top 42-28. The Cardinals didn't even kick the last PAT. It was just awarded to them.

At some point in the final quarter - the newspapers are hazy about when - a brawl broke out between the teams. Among the combatants were the two coaches, George Halas and Milan Creighton, who traded blows until they were sent to neutral corners. "To add to the general confusion," the Chicago Herald and Examiner reported:

L-R: Gaynell Tinsley, George Halas, Milan Creighton ... there remained the annual closing clash with the Cardinals, a game for which the script must have been written by the Marx brothers. It contained everything from laughs to a fist fight in which, as usual, the peacemaker was the only one to get punched. It wound up in total darkness and with bonfires blazing here and there in the stands as congealed spectators strove in vain to keep warm. Only a chorus was lacking to spoil the musical-comedy aspect of the affair. The Bears won, 42 to 28, the combined totals establishing a record for points scored in a single game. Other marks were set, too, 64 passes being thrown and 30 completed for 501y, but these were merely incidental happenings of a completely daffy day. It was bitter cold; the field was frozen and covered with a solid coating of ice on the south end from the goal line out beyond the thirty. Both teams wore tennis shoes, but to no avail. Not even a mountain goat could have maintained his footing on such a surface. Hands and faces were slashed as if by razor blades from contact with the ice. While the score was still close, Halas and Milan Creighton, the Cardinal coach, became embroiled in a violent dispute that wound up in a flurry of punches. Neither coach was so much as bruised, but an errant wild pitch thrown by one of them caught referee Bobie Cahn flush on the jaw. Little Bobie had absorbed lots of bumps in his years of officiating among the professional giants and took such happenings in good-humored stride. He simply chased the rival coaches back to the bench and ordered play resumed. Creighton wasn't so lucky in an earlier brush with another official, Jim Durfee. The young Cardinals coach had stormed onto the field to protest a Durfee decision, and Jim had retaliated by stepping off a 10y penalty against him. "What's that for?" demanded the indignant and apopletic Creighton. "That's for running out here on the field," Durfee answered. "That's not a 10y penalty," Creighton protested. "It should be 15y." "Yeah, I know," grinned the imperturbable Durfee, "but you're not worth that many!" ..., darkness began to fall, blanketing the field so rapidly and completely that soon the only thing visible from the stands was the white pants of the Cardinal players. Suddenly, from near one goal line, a pair of those white pants streaked off madly toward the opposite goal. A moment later, from the flickering light of grandstand bonfires, the players could be seen trooping from the field. Puzzled sports writers, in the dark in more ways than one, discovered what had happened only by visiting the dressing room. The pants racing the length of the field belonged to Gaynell Tinsley. The Cardinal end had sprinted 95y on an end-around for a TD as the Bears wondered what in the world had become of the ball. When Tinsley crossed the Bear goal line the officials decided to award the Cardinals the extra point without going through the formality of kicking it, and then called the whole thing off. Exactly two minutes and fifty-one seconds of that game were never played. Ole Miss Football, Lawrence Wells (1980)

En route to a 9-2 season, … Ole Miss met Arkansas in Memphis on Nov. 16, 1938. [Coach Harry] Mehre's Notre Dame Shift proved too much for the Razorbacks, who fell, 20-14, in a game marked by savage hitting.

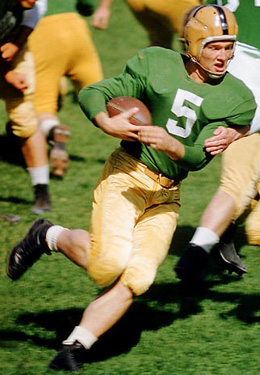

In a play that Ole Miss (and Arkansas) fans still talk about, "Wild Bill" Schneller, junior QB from Illinois, intercepted an Arkansas pass and raced up the sidelines untouched for a score. As he approached the 20y line, Schneller turned in mid-stride, placed his thumb on his nose, and wriggled his fingers at the nearest Arkansas pursuers in an unmistakable gesture. He thumbed his nose again as he crossed the goal line. The Arkansas crowd was furious. In the bitter scrimmaging that followed, Winky Autrey, the Ole Miss C, tackled Zack Smith so hard that the Arkansas back had to be taken to the hospital.  L: "Wild Bill" Schneller; R: Schneller after intercepting against Arkansas

"When the gun sounded," Tad Smith recalls, "the fans poured out on the field to fight. It was wild. People were fighting everywhere. I got behind the bench, out of the way, looked down, and there was Winky Autrey, hiding under the bench!"

Nothing Comes Easy: My Life in Football, Y. A. Tittle with Kristine Setting Clark (2009)

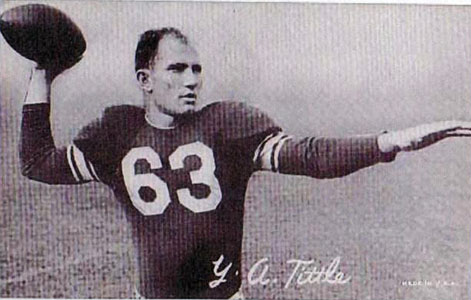

The Baltimore Colts met the Buffalo Bills in a playoff for the Eastern Division championship of the All-America Football Conference in Baltimore on December 12, 1948, Y. A. Tittle's rookie season as quarterback of the Colts.  Y. A. Tittle with the Colts Five days before our game with Buffalo, I was summoned to a players' meeting after practice. I sensed something was wrong, and it was. The veterans ... felt that the team should get their share of the gate receipts since there was no provision in their contract to cover the possibility of a playoff. Tempers flared, and finally Ernie Blandin and Dick Barwegan were employed to convey the team's demands to Colts president Jake Embry ...

After listening to Blandin and Barwegan, Embry explained the position of the front office. "We feel a divisional playoff is part of a player's regular contract. Also, we are having a difficult time staying in the black. This extra game could put us on solid ground. We would appreciate the players' understanding in this matter." Blandin explained that if the players didn't get a portion of the gate receipts, there would be a possibility of a strike on Sunday, but his proclamation fell on deaf ears. Both Blandin and Barwegan reiterated the requests of the front office to the players, who at this point insisted on a strike if their demands weren't met. Word got back to Embry ... who told the team, "If you don't want to play the game, we will announce to the public that the title has been forfeited to Buffalo. We will consider the season over, and we will all go home." A second players' meeting was called to vote on whether to play or not. The decision to play was announced. There was much resentment within the team after that day. ...

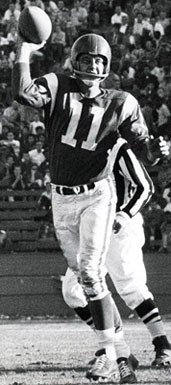

Baltimore dominated the third quarter. After marching 71y downfield, Bus Mertes scored on a 9y run. Grossman kicked the conversion and we were up 10-7. Next we marched 87y, and again Mertes scored, this time on a 1y run with Grossman contributing the extra point. The score was 17-7. In the fourth quarter Ratterman and Bill Gompers connected on a 66y scoring pass to cut our lead by three. The Bills regained possession late in the fourth quarter. It was a race against the clock.  George Ratterman When the final gun sounded, the irate Colts fans stormed the field. Their target was head linesman Tommy Whelan. They were furious about the call he had made earlier in the quarter. Extra police were brought on to the field to protect Whelan from the crowd. Both Buffalo and Colts players escorted the head linesman to the dressing room through the hostile, bottle-throwing crowd. When he finally got inside, I noticed that he had a swollen eye and his mouth had been cut. The mob had even torn the back of his shirt. I know he was scared half to death, and I didn't blame him one bit. Even though the police tried to calm down the angry mob, they continued yelling for Whelan: "Let's get Whelan! Let's get Whelan!" It was the wildest, not to mention scariest, professional football game that I had ever encountered. Fistfights arose throughout the stadium as did fires in the stands. People were being knocked down. They protested outside the Stadium Administration Building and refused to move until Whelan came out. Whelan and the Bills team were huddled inside the building trying to come up with a way to elude the frenzied mob outside. They were finally able to smuggle out the head linesman among the Buffalo players. They all made it safely to their chartered bus right under the noses of those insane fans.

"Anger Spurs Eagle Center to Action," George Esper (AP article Oct. 23, 1960)

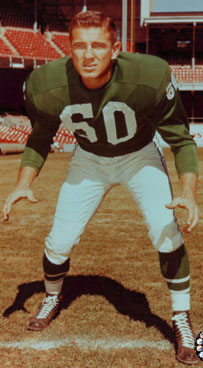

Chuck Bednarik said today inspiration and anger toward Cleveland Coach Paul Brown for laughing at him drove him to the unusual feat of playing 58 minutew and a key role in the Philadelphia Eagles 31-29 victory over the Browns Sunday. The former Penn All-America center said Brown laughed at him "real loud" when someone blocked him hard near the Browns' bench in the second quarter.   L: Chuck Bednarik; R: Paul Brown "I hollered back something at him that is unprintable, but in the heat of battle you're liable to say anything. Anyhow, his laughing annoyed me. "We wanted to win badly from the start for the previous humiliating loss but when he laughed that only made me want to win worse. The weather helped go the 58 minutes, too. It was a cool day, about in the high 40s. "And then there's the mental thing, no matter what we do in life. If you tell yourself you can do something, you can. I kept talking to myself saying, "You're not tired," and I wasn't." Bednarik, who played most of the game with a pulled leg muscle, said he worried more about Cleveland's Jimmy Brown and Bobby Mitchell "because no other team has a combination like them ... corner LBs have to help by coming back into the center of the line to stop Brown ... you have to contain Mitchell because once he skirts a corner he can fake so well he doesn't need blocking." The 35-year-old Bednarik played what he felt was the best game of his 16 years in college and professional football. His offensive blocking was outstanding and his hard tackling helped stop HB Mitchell, allowing him only 35y in 14 carries, as the Eagles handed the Browns their first NFL loss this year and pushed them into third place in the Eastern Conference. The Eagles moved into second place, avenging a previous 41-24 loss in Philadelphia Sept. 24 when Mitchell gained 156y in 14 carries and scored two touchdowns on runs of 30 and 31y. QB Norm Van Brocklin, who passed for 292y and three TDs, said he felt it was his best performance of the year and the victory "puts us in a real good position" for the title.    L: Norm Van Brocklin; C: Jim Brown; R: Bobby Mitchell Van Brocklin, shunning praise for himself, said "the biggest thing was our ability to run up the middle." He said Bednarik helped to open many of the holes. Postscript: The Eagles won the NFL championship that year, handing Vince Lombardi his only title game loss in his years at Green Bay.

In the Arena, Pat Dye with John Logue (1992)

Pat began his coaching career in 1965 as an assistant to Bear Bryant.

September came around. And the first game I went into in my life as a football coach was against Georgia, my old school. In Athens. And they beat us with the flea-flicker pass.

Kirby Moore of Dothan, Alabama, passed the ball to Pat Hodgson, who, with both knees on the ground, lateralled it to Bob Taylor of Headland, Alabama, who ran the rest of the 72 yards for a touchdown. Then Moore hit Hodgson for a two-point pass to put Georgia ahead, 18-17, with two minutes to play. ... We got whipped, and Coach Bryant stood in the dressing room after the game. He said, "Men, it's kinda obvious that we don't have a very good football team. But if you are the kinda people I think you are, we'll have a good football team before the year's over. Get on the bus and let's go back home. And be ready to go to work Monday."

Monday, all hell broke loose. I mean, you talk about young coaches, old coaches, and Coach Bryant working - we started, and we built a football team. Of course, we went on to win the National Championship. But not without a struggle. I think there were eight or nine guys who started against Georgia who never started another game the whole time they were at Alabama.

On Monday - oh, Lord - it was just an all-out war. Scrimmaging. Pickin' 'em up and makin' 'em go when they were exhausted. We had to know who wanted to play for Alabama. ... The next week we played Tulane. And killed 'em. Ole Miss was coming up. ... We had a bad practice. Coach Bryant got involved in the kicking game. Nothing was going the way he wanted it to go. He ran everybody off the field, players and coaches. In the dressing room, he talked to the players first. Then he talked to us coaches. He said, "We're going to practice in the morning at 5:30. I'm telling y'all like I told the players. Anybody who doesn't want to make it, just pack your damn bags, and I'll mail your damn check." Dude Hennessey slept in the coliseum he was so scared he'd go home and not wake up in time. The next morning I got over to the coliseum early. Our C, Billy Johnson, met me. He was about in tears. He said, "Coach, Wayne Cook ain't coming." Wayne was our starting TE. I said, "The hell he ain't." I jumped in my car and went over to the dorm. Wayne was laying up there in the bed. I said, "Get up. Let's go." He said, "I'm not going, coach." I said, "You're going. Or I'm gonna whip your ass, or you're gonna whip mine. Right here." Then I said, "Wayne, if you are gonna quit, don't lie up here in the bed and quit like a coward. Go on to practice. Don't let the man intimidate you and make you say it's too tough for you. If you want to quit after practice, walk in his office and quit like a man. This ain't the way to do it." He got up, and we went to practice. And, of course, he never did quit. The players dressed out. Coach Bryant himself loosened them up. He did all the coaching. The rest of us just stood back out of the way. He took the first offense and put 'em against the second defense on the goal line. Ran six or eight plays. He put the second offense against the first defense and ran six or eight plays. He lined up the punting team and protected and covered punts three or four times. We weren't out there over 15 minutes. But damn, they were wild-eyed, flying-through-the-air, bodies-and-snot-flying minutes. When it was over, Coach Bryant said, "I ain't got you out here this morning to punish you. I could think of a thousand ways to punish you." He said, "I want you to know something. As long as I am the football coach at Alabama, and I let you get by with less than the best you've got, then I'm doing you an injustice." He said, "Now y'all go on in there and get a shower and go to class. Don't go back to the dorm and lay up in the bed. I'll see you at four o'clock." We came back at four. And we worked. ...  Bear Bryant and Pat Dye coaching at Alabama At the end of the season we were ranked No. 5. I believe Michigan State and Nebraska and Arkansas were all undefeated. They all lost in the bowls. We played Nebraska in the Orange Bowl at night. We knew if we beat Nebraska we would be No. 1. A lot of strategy went into our game. Nebraska was good, but slow. It was before they recruited the great speed. Our plan was throw as much as we could and wear them out on defense from rushing the passer. Coach Bryant had a lot to do with that strategy. We built up a 24 to 7 lead in the first half, with [Steve] Sloan passing. And we ran it on them real well the second half, with Les Kelley and Steve Bowman carrying the ball. We won, 39-28. We'd come a heck of a long way since losing to Georgia on the flea-flicker. It was the greatest coaching job done at Alabama in the years I was there.

The Whole Ten Yards, Frank Gifford with Harry Waters (1993)

A guy in ABC’s research department recently told me that I've appeared more hours on prime-time television than anyone in the medium's history. … Most of those appearances, of course, have been on a series that's earned its own niche in TV history. Don Meredith called it Mother Love's Traveling Freak Show. … I feel sorry for anyone who has never been involved in something like Monday Night Football. …

L-R: Don Meredith, Howard Cosell, Frank Gifford At times we could have used less excitement. First of all, football fans going to 9:00 P.M. games in the Eastern Time Zone tend to make lubrication stops after work. Four hours later, they're often more a mob than a crowd. We needed guards to keep them from knocking down the door to our booth and police escorts to get out of the stadium. … A few of those people wanted Howard dead. Seriously dead. Like on that weird Monday night in Buffalo in 1973.

It started on the plane when I noticed two somber-looking guys getting aboard with Howard. "Giffer," he informed me, "these gentlemen are FBI agents here to protect me. There's been a threat on my life." Naturally, Don and I laughed like hell. "Don't worry, old pal," we assured him. "We'll look after you." Then, on the way to the hotel, Howard filled us in a bit more. The crazy who had threatened him – via a postcard postmarked Buffalo – had promised to blow up the ABC booth at halftime. Since Don and I would also occupy that booth, we no longer saw quite so much humor in Howard's predicament. As a matter of fact, we were suddenly seriously concerned about his well-being. That was the longest two quarters I ever broadcast. And when halftime finally arrived, an odd thing happened. First Don stood up, stretched his legs, and announced, "I'm a-goin' to the head." Then Howard arose, patted me on the shoulder, and said, "Giffer, I've got to do a couple of radio spots. I'll be right back." For the next twenty minutes, I felt like Gary Cooper in High Noon. Though we didn't explode, Buffalo wasn't finished with us. Toward the end of the game, a well-oiled fan climbed up on a cable that ran across the stadium at the back of the end zone. The cable help up a screen that prevented extra points from going into the crowd. As he inched along his death-defying route, I'm trying to do the play-by-play. Meanwhile, Howard is off on another of his fan-bashing acts: "Giffer, it is beyond my perspicacity why spectators of this once-splendiferous sport behave the way they do. How can the NFL allow this execrable rowdiness to continue?" Don, on the other hand, had concluded that the Houdini act was better than the game. Echoing the crowd, he started chanting, "Go, sucker, GO!" Mercifully, the police eventually talked the guy down and, I presume, took him away in a net. Leaving the game ourselves, we felt so drained that we decided we needed nutrition. All of a sudden, everyone wanted a cheeseburger. Since our hotel didn't have room service, we instructed our limo driver to find us a McDonald's. He did – in the toughest part of town. When we pulled into the parking lot, a half-dozen of the meanest-looking dudes I've ever seen were lounging against some cars. Howard took one peek out the window and quickly said, "Giffer, perhaps we better move on." So Don and I got out and headed for the entrance, Don in his cowboy hat and walking like Marshall Dillon. Blood, Sweat and Cheers: Great Rivalries of the Big Ten, Todd Mishler (2007)

Indiana hasn't been at the top of the league standings since 1967, when it shared the title and participated in the school's first and only Rose Bowl on January 1, 1968. Nevertheless, the Hoosiers continue to show up every Saturday and display as much school pride as anybody else, even though that's all they've had to show for their efforts during many long seasons.

One such example is the Hoosiers' series against Michigan State, a grudge match after which the winner gains the Old Brass Spittoon, a prized possession they've wrestled over since 1950. The battered spittoon comes from a Michigan trading post and is more than 100 years old. The junior and senior classes, and student council at Michigan State initiated the award. The intrigue and gamesmanship boost the interest and add to the excitement, especially for the squad that hasn't tasted victory in a while. After Indiana's 37-28 triumph at East Lansing in 2001, the Hoosiers refused to leave the field until Michigan State surrendered the spittoon, a situation that had rankled Indiana ever since the visitors failed to bring it to Bloomington for their 1991 tussle. [Indiana coach] Bill Mallory summoned an assistant to retrieve the treasured item, but the Hoosiers found out that their spoils had been mistakenly shipped to Iowa instead.  Flutie, Doug Flutie with Perry Lefko (1999)

After Pop Warner, I started playing junior high school football [in Natick MA]. I had a coach named Kirk Buschenfeldt, who was probably one of the first people to realize I was thinking ahead of the other guys. He made me memorize all the plays and the formations that go with them so I could call my own plays. Here I was at age 14, in ninth grade …, calling my own plays and running my own show. …

Kirk Buschenfeldt told my high-school coaches that he thought there was something special about me, and to give me a look and not let me get lost in the shuffle. Kirk told them he thought I had the best hand-eye coordination of any athlete he had ever seen. The first day the high school coaches made me practice with all the sophomores at the other field. I did very well … The second day they brought me up to the varsity … Within a couple of days … I started rotating in at free safety and wide receiver – but they knew I was a quarterback. We started out 3-0, but we struggled offensively. The fourth game we played Wellesley, a team we should have beaten, but lost 8-6. Our coach … was really upset about it. … the next week against Milton, I started at QB and [Doug's older brother] Bill was moved to receiver [from QB]. … In the first half against Milton, I threw four interceptions. The coaches were kind of second-guessing themselves, but in the second half I threw three touchdowns. We scored a mess of points and won the game. Bill and I never left the field. We returned kicks and punts. I was the FG kicker and kickoff guy, and Bill was the punter. It turned out to be a useful piece of equipment – sort of. In the final game of my sophomore year against Braintree, the opposition scored late in the final minute of the game to lead 25-24. We took possession with 19 seconds left and I threw three straight balls to Bill, who fell down on his knees on the final catch at the 21-yard line with three seconds left on the clock. I had kicked extra points but never any FGs, and this was a 38-yarder. I went to the sidelines to put the square toe shoe on, but I couldn't get my regular shoe off. The coaches had to rip it off my foot. When I tried to tie the square toe shoe on, the shoelace broke, so I tied that off half way down. While I was rushing to do this, I didn't have any time to become nervous about the kick. I just ran out, lined up – Bill was the holder – and I pumped the thing through. I probably hit the best ball of my life. Bill Flutie: It was a shocker. I don't think the Braintree guys thought it was a realistic thing and they kind of didn't even rush. They stood there, and Doug just pumped that thing. It sailed way over the goalpost. It would have made it from 50 yards out. No question. He just bombed it straight down the middle. |