The first football conference was formed on November 23, 1876, when representatives of Yale, Harvard, Princeton, and Columbia met at the Massasoit Hotel in Springfield MA for the purpose of forming the Intercollegiate Football Association. The schools hoped to bring order to the chaos of collegiate sports, particularly football. At that point, the schools (all in the northeast) that played "football" vacillated between a game more akin to soccer vs. a game more like rugby, the "hands-on" version of football.

After meeting for more than three hours, the representatives voted 3-to-1 to reduce the size of a squad from 15 to 11. However, Yale was the "1" and objected so strongly that the Eli pulled out of the new organization. It was three years before Yale joined the association at the urging of its captain, Walter Camp.

At least two schools, both in the Ivy League, claim the first football scoreboard.

- Harvard says that, on November 30, 1893, its Athletic Association unveiled the invention of Arthur Irwin, a Bostonian and a professional baseball player and manager, in the Crimson's 26-4 win over Pennsylvania before 16,000 on Thanksgiving Day. However, the New York Times article on the contest the next day makes no mention of any scoreboard. Obviously no lights were used because the article says, "The game closed in darkness, and the final plays were indistinguishable."

- Pennsylvania claims that, when 10,000-seat Franklin Field was built in 1895 at a cost of $100,000, it boasted the first scoreboard. ESPN's College Football Encyclopedia gives the honor to Penn. Again, the brief New York Times report on the Quakers' October 1 opener, a 40-0 victory over Swarthmore before only 1,500, makes no mention of any scoreboard or even that the game was the inaugural contest in the new stadium.

|

Franklin Field 1895 –Penn-Harvard game.

That might be a scoreboard in the haze at the far end of the field. |

|

Pro Football 100,000 Crowd

On November 10, 1957, the Los Angeles Rams defeated the San Francisco 49ers 37-24.

- The significance of this game is that it was the first pro football game played before a crowd in excess of 100,000, 102,368 to be exact in the Los Angeles Coliseum.

- The figure easily surpassed the previous record NFL crowd of 93,751 in the same stadium in 1953 when LA hosted the Detroit Lions. (95,985 had attended a 1951 exhibition game between the Washington Redskins and the Rams.)

- An estimated 10,000 more fans were turned away when the last ticket was sold.

The Los Angeles Coliseum

Norm Van Brocklin's pinpoint passing (14-23/224/2TD) sparked the Los Angeles victory over the 49ers of Frankie Albert.

- Bob Boyd caught TDs of 50 and 15 yds for Sid Gillman's Rams.

- Y.A. Tittle (12-23/147/1TD) threw a 22yd TD for the visitors to RB Hugh McIlhenny. The former LSU QB also sneaked 1 yd for a score.

- After the Rams led 28-17 at the half, the second stanza proved more sedate.

|

On December 8-9, 1932, the 23-member Southern Conference held its annual meeting in Knoxville, TN.

- However, the 13 members west and south of the Appalachian Mountains, believing the conference had become too large and far-flung, reorganized as the Southeastern Conference. Ten of the original 13 members remain in the SEC: Alabama, Auburn, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana State, Mississippi, Mississippi State, Tennessee, and Vanderbilt. The other three charter members were Georgia Tech, Sewanee, and Tulane.

The first SEC football games were played on Saturday, October 7, 1933.

- Jacksonville: Florida whacked Sewanee 31-6.

- Athens: Georgia downed Tulane 26-13.

- Knoxville: Tennessee shutout Mississippi State 20-0.

- Lexington: Kentucky edged Georgia Tech 7-6.

- Birmingham: Alabama and Ole Miss tied 0-0.

LSU didn't play its first conference game until October 28 when the Tigers tied Vanderbilt 7-7 in Baton Rouge.

Alabama won the first conference championship with a 5-0-1 record. The Tide have won or shared 20 more SEC gridiron crowns. |

Alabama Coach Frank Thomas

Paul Bryant

Alabama RE

1933

|

In 1880, after several years of trying, Walter Camp, having just graduated from Harvard and entered medical school, finally persuaded the rules committee to reduce the number of players on the field from fifteen to eleven. Camp offered several arguments for his proposal.

- Fewer players meant fewer difficulties gaining faculty permission to travel.

- The possibilities for open field strategies would increase, making the game both safer and more exciting.

|

Football Wedge Formation Football Wedge Formation |

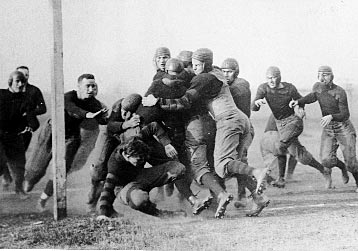

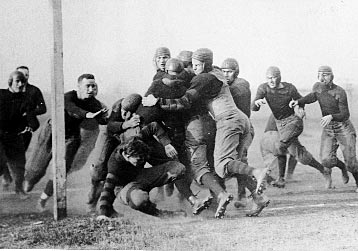

The straight wedge (as opposed to the flying wedge) was first used on October 25, 1884, by Princeton against Pennsylvania at Philadelphia. The Tigers gained 45 yd. Also called the "V-trick," the formation put the ball carrier in the middle of the V. Since the rules did not require any set number of players on the line of scrimmage, all players other than the center (the point of the V) could lineup any distance they wanted behind the line.

For every offense, opponents devise a defense. One of the popular methods of attacking the wedge was to hit the apex man in the jaw. Another approach was for defensive players to dive under the legs of the men in the wedge, knocking them down to strip away the ball carrier's interference. Eventually, Yale's Pudge Heffelfinger invented the ultimate defense. He took a running leap, drew up his knees, and smashed into the center.

Understandably, football quickly became known for its violence. "There is no sport outside of a bullfight that provides the same degree of ferocity, danger and excitement as that shown in an ordinary intercollegiate game of football," wrote the New York Herald.

Reference: NCAA: The Voice of College Sports, Jack Falla

|

|

First Coast-to-Coast TV Game

The 1951 college football season saw several firsts related to television.

- September 22 - NBC telecasts the first live sporting event seen coast-to-coast, a college football game between Duke and Pittsburgh in the Steel City. (The game was not seen in New Orleans because the coaxial cable was not extended to the Crescent City until the summer of 1952.)

- The first SEC game to be nationally televised occurs October 20, 1951: Tennessee-Alabama at Legion Field in Birmingham.

These national broadcasts resulted from a very cautious approach taken by the NCAA to televising its major revenue sport, football.

- As television blossoms after World War II, individual colleges such as Notre Dame and Penn sign contracts with broadcasters to televise their games.

- The NCAA's fear, however, is that live telecasts will reduce attendance at games, not only for the televised games themselves but also at other games because a certain percentage of fans will stay home to watch a TV game rather than attend a game in their area, especially in bad weather.

- The January 1950 NCAA Convention forms a Television Committee charged with examining the issue of college sports on TV. A few months later, without waiting for the Committee's report, the Big Ten adopts a ban on television of football games by its members.

- The Television Committee hires the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) to research the effect of television on football attendance. The first NORC report (August 1950) supports the position that TV has an adverse effect on attendance.

- For the 1950 season, the NCAA has no restrictions on football telecasting. So some college games are telecast in limited areas but none nationally. For example, ABC televises every Penn game regionally for $150,000.

- The January 1951 NCAA Convention votes 161-7 to declare a moratorium of live telecasting of football games by individual schools and calls on all members to cooperate in an experimental television plan to be developed by the TV committee.

- The plan eventually calls for one designated game of the week on most Saturdays of the season.

- However, there will be blackouts on certain Saturdays in parts of the country, including a complete blackout nationwide on November 10.

- After the one-year experiment, the membership in January 1952 adopts the basic plan crafted by its TV committee: total control by the NCAA with one national telecast each week.

|

|

Football Rankings

The first person to rank college football teams was Frank Dickinson, a professor of economics at the University of Illinois, in the early 1920s.

- In 1926, Dickinson told one of his classes about a method he had developed for ranking football teams. One student in the class was the editor of the Daily Illini. He wrote an article about Dickinson's system.

- Jack Rissman, a Chicago clothing manufacturer, read the article and approached Dickinson about using his system to determine the Western Conference champion each year since the teams in the Big Nine, as it was commonly called, did not all play each other. Rissman offered to donate a trophy to be awarded to the annual winner.

- Knute Rockne, the coach at Notre Dame, learned of the plan and invited Dickinson and Rissman to meet with him at South Bend, where he suggested they expand the system to all teams in the nation so that the Irish would have a chance to win it. Knute also suggested that Dickinson apply his formulas retroactively to the 1924 and 1925 seasons.

- Dickinson's system ranked teams based on strength of schedule as well as number of wins and losses.

- Each game earned each team a score based on the outcome (win, loss, or tie) and the quality of the opponent.

- The professor divided teams into "first division" (.500 or better) and "second division" (below .500). A loss against a first division team earned you 15 points while a win against a second division team earned only 20.

- However, Dickinson introduced bias into his system with "differential points" for intersectional games. Eastern teams were assigned 0 differential points, "Middlewest" teams +4.77, Southwest +1.36, and Big Six +2.60. However, differential for the South was -2.59 and the Pacific Coast -2.71. So if a team beat or lost to a Midwest squad, it got 4.77 points added to its score. However, playing a Southern team knocked 2.59 points off the game's value.

- As Rockne suspected, Dickinson's calculations gave Notre Dame's "Four Horsemen" team the 1924 championship. The 1925 retroactive winner was Dartmouth.

- Dickinson hand-calculated Stanford as the 1926 winner of the Rissman National Trophy. In 1927, Dickinson's own Illini won the title.

- Notre Dame topped the rankings in 1929, then won again in 1930. Under the rules set up, a school that won the award for the third time retired the trophy to its campus. However, Rissman provided another one.

- For the 1931 season, the first one after the ND coach died in a plane crash, the trophy was renamed the Knute K. Rockne Intercollegiate Memorial Trophy.

- Dickinson's system was applied through the 1940 season, when Minnesota became the second school to retire the trophy after three wins.

Within a few years of the unveiling of Dickinson's system in 1926, other rating schemes sprang up. We'll revisit this topic in the future.

|

Knute Rockne |

|

Egg Bowl

In 1926, Ole Miss defeated Mississippi A&M 7-6 at Scott Field in Starkville. This set off jubilation among the Rebel fans who had suffered through 13 straight losses to their rivals by the combined score of 327-33.

- While the Aggie team left the field with heads bowed as the Maroon student section sang the alma mater, the Rebel partisans rushed "like madmen onto the field."

- Some Rebels made a beeline for the goal posts. Irate Aggie supporters set out to stop their stanchions from being torn down.

- Fights broke out, and Maroon fans wielded cane bottom chairs until most of them were splintered. As the A&M yearbook later explained, "A few chairs had to be sacrified over the heads of these to persuade them that was entirely the wrong attitude."

Ole Miss and A&M student leaders, appalled by "The Battle of Starkville," vowed to prevent such a scene from happening again.

- Members of Sigma Iota, Mississippi's honorary society, proposed a trophy to be presented in a dignified ceremony right after the annual game. A&M approved the idea, and the award, called "The Golden Egg," was produced for $250, the cost to be shared by both schools.

- A proposal that the goal posts be kept by the winning team each year was rejected.

The first Battle of the Golden Egg took place on Thanksgiving Day 1927 at Oxford.

- 14,000 saw Ole Miss win for the second year in a row, 20-12.

- The Jackson Clarion-Herald reported: "On the sidelines a band garbed in red and blue played 'Give 'em Hell, Mississippi" and on the gridiron a team wearing the same colors did that very thing."

- Immediately following the game, the "dignified ceremony" took place. As previously agreed, each school sang its alma mater with the winning side going first. Then the captains of the two teams, presidents of the student bodies, and heads of the two schools met in the center of the field. The president of A&M presented the Golden Egg to the chancellor of Ole Miss, who turned it over to his captain.

The '29 game ended in a 7-7 tie.

- So each team kept the Egg for six months starting with Ole Miss, the previous year's winner.

- Mississippi State (as the school was renamed in 1932) finally captured the trophy outright in 1936.

- Ole Miss won every game from 1947 through 1963 except for two 7-7 ties.

- State has never won more than four in a row (1939-1942).

After alternating between the two campuses, the Egg Bowl, as it came to be known in 1977, was contested in Jackson from 1973-1990 before returning to the campuses. Ole Miss's 45-0 victory in 2008 brought the series record to 54-22-5 in favor of the Rebels. Reference: 2008 Ole Miss Rebel Media Guide, www.olemisssports.com

|

|

|

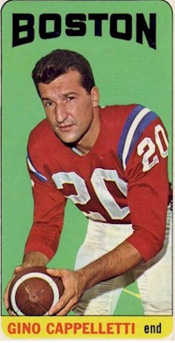

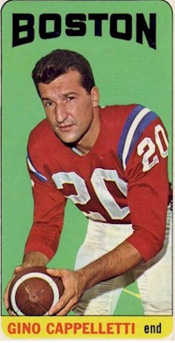

Al "Hoagy" Carmichael

Eugene Mingo (#21) against the Patriots in the first AFL game

|

Date/Time: Friday, September 9, 1960, 8 pm

Site: Boston University Field

Teams: Boston Patriots vs Denver Broncos

The American Football League began with eight teams.

East |

West |

Boston Patriots |

Dallas Texans |

Buffalo Bills |

Denver Broncos |

Houston Oilers |

Los Angeles Chargers |

New York Titans |

Oakland Raiders |

Eight owners had banned together to audaciously challenge the mighty NFL. The AFL had conducted its own draft and signed some the top college seniors, including Heisman Trophy winner Billy Cannon (Houston Oilers) and his LSU teammate Johnny Robinson (Dallas), and Ron Mix USC T (Los Angeles).

Boston and Denver got the distinction of playing the first game because it was scheduled for Friday night. The other three games would be played on Saturday or Sunday. The league had signed a TV contract with ABC, but the first telecast would not be until Sunday.

- Frank Filchock coached the Broncos. He had played six seasons at TB in the NFL, primarily with the Washington Redskins. Then he coached in Canada.

- Lou Saban coached the Patriots. A lineman, Lou had played four years in the AAFC for the Cleveland Browns.

The Patriots, who had beaten Denver 43-6 in an exhibition game a few weeks earlier, elected to kickoff when they won the toss. So Tony Discenzo, 245-lb T from Michigan State, got to initiate action by kicking off on the muggy night before 21,597.

- Denver's O was led by 33-year-old QB Frank Tripucka from Notre Dame. Like most of the AFL players, Frank had played in the NFL from 1949-52 with the Detroit Lions and Chicago Cardinals. He then played Canadian football.

- The Broncos first drive went nowhere, and they punted to the Patriots. Out came Butch Songin to run the O. He had starred at Boston College in hockey as well as football. Three years older than Tripucka, he had never played pro football before. Aided by a roughing the punter penalty, Boston drove to the Denver 34 where Gino Cappelletti kicked a FG to record the first points in AFL history. Cappelletti played DB that night but was soon switched to FL, where he became one of the most productive Patriots in the early years.

- On the first play of Q2, Tripucki tossed a pass in the right flat to Al Carmichael from USC who had played six seasons with Green Bay. Carmichael reversed field and went down the left sidelines for a 59yd TD, the first TD in AFL history. Gene Mingo kicked the first PAT in league history to put Denver up 7-3. There was no more scoring in the first half.

- Tommy Greene, another local hero from Holy Cross, replaced Songin at QB in the second half. The fans had yelled for him but when he failed to move the team in two series, they wanted Songin again. Mingo fielded a punt and sped 76 yd down the right sideline for a TD. His PAT was wide, leaving the score 13-3 with 2:48 left in Q3.

- After Denver recovered a fumble, "Cowboy Jim" Crawford returned an INT 40 yards to the 13. Songin then fired a pass to rookie Jim Coclough for the Patriots first TD ever. Cappelletti added the first of his 342 career conversions.

- Late in the game, Songin flipped a screen pass to former Wyoming star "Cowboy Jim" Crawford who rambled 40 yards to the 13. However, the Patriots lost yardage and a third-and-17 pass was intercepted on the two. Denver then held the ball for 18 plays to run out the clock.

Reference: "The First AFL Game," Larry Bornstein, The Coffin Corner, 1980

|

|

In 1956, John Campbell and George Sarles showed coach Paul Brown of the Cleveland Browns a radio receiver they had invented. They suggested that the device could be placed in a helmet to enable Brown to communicate with players on the field from the sidelines.

Brown provided the inventors with the helmet of QB George Ratterman and authorized them to mount the receiver inside it and test it thoroughly in secret before it would be used in an actual game. The test nearly backfired. Sarles took the helmet into the woods behind Campbell's home and atte mpted to communicate with Campbell. However, the signal broke off, and Campbell went looking for Sarles. He found him with a policeman who had intercepted the signal. Fortunately, the officer was a Browns' fans and agreed to keep the secret. However, the inventors changed the frequency on the unit.

The helmet was first used in an exhibition game against Detroit. The Lions coaching staff became suspicious when they noticed that Brown was not employing his usual messenger guards to send in plays. Shortly after halftime, one of the Lions' assistants spotted the transmitter behind a post on the sideline.

News spread through the league, and other teams hurried to concoct their own units. Brown used the device in three more games before NFL Commissioner Bert Bell outlawed it.

There were also some glitches. OT Mike McCormack tells the story of one game when Ratterman got a funny look on his face in the huddle. "I'm getting calls for taxicabs," George said.

It was not until 1994 that the NFL approved the use of transmitters in helmets for communication with QBs. And only in 2008 did the league allow a similar setup for a designated defensive player.

|

Paul Brown communicates via walkie-talkie during an October 19, 1956 game just before Commissioner Bert Bell banned the helmet receiver. |

|

Flying Wedge |

To start the second half of its annual grudge match with Yale in 1892, Harvard unleashed what Amos Alonzo Stagg later called "the most spectacular single formation ever opened as a surprise package. It was a great play when perfectly executed, but, demanding the exact coordination of eleven men, extremely difficult to execute properly." He was referring to the infamous "flying wedge," a ploy that injured many players and almost killed the sport itself.

The flying wedge was used on the kickoff because the rules called for a team to begin the half by kicking the ball to itself, as is still done in soccer. So Lorin Deland, a military tactician, chess aficionado, and Harvard supporter, divided the eleven players into two groups of five stationed at opposite sidelines. When captain Bernie Trafford gave the signal, each group sprinted diagonally toward the center of the field. As the groups reached full speed, Trafford tapped the ball to his running back, Charlie Brewer. At that point one of the groups of five executed a quarter of a turn so that the wedge would be focused at Yale's weakest defenders. The play gained 30 yards before the pursuit stacked it up by grabbing the legs of both the blockers and the ball carrier.

The flying wedge has been called "a sort of gridiron kamikaze weapon forged of human bodies" (John Sayle Watterson, College Football: History, Spectacle, Controversy). The New York Times gushed: "What a grand play! A half ton of bone and muscle coming into collision with a man weighing 160 or 170 pounds." News of the sensational innovation spread quickly and by the next season the tactic was in widespread use.

The flying wedge made football much more exciting for the spectators but much more dangerous for the participants. |

Reference: NCAA: The Voice of College Sports, Jack Falla

|

CONTENTS

Conference

Scoreboard

Pro Football 100,000 Crowd

SEC Champions

Eleven on a Side

Straight Wedge

Coast-to-Coast TV Game

Football Rankings

Egg Bowl

AFL Game

Helmet Radio

Flying Wedge

Football Firsts – I

Football Firsts – III

Football Firsts – IV

Football Magazine

Golden Rankings Home

Top of This Page |

Football Wedge Formation

Football Wedge Formation