CONTENTS

Lombardi and Bryant

The Rise of Southern Football

From Homeless to the NFL

When Army Sang "Anchors Aweigh"

Football Players on TV

Political Players

Weirdest Team in NFL History

NFL Fumbled Earlier Chances before '58

Sugar Bowl Travel Restrictions

1926 Rules Changes

Football:

Did You Know? I

Football: Did You

Know? II

Football: Did You

Know? III

Football: Did You

Know? IV

Football: Did You

Know? V

Football: Did You

Know? VI

Football Magazine

Golden Rankings Home

Top of Page |

Football:

Did You Know? – VII

|

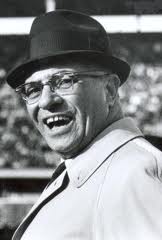

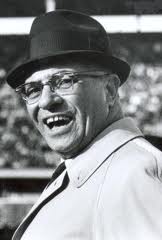

Lombardi and Bryant

Paul "Bear" Bryant |

In the preface to his book The Last Coach: The Life of Paul "Bear" Bryant, Allen Barra points out the uncanny similarities between two of the greatest coaches, Bear Bryant and Vince Lombardi.

- Both were born in 1913, Bryant in rural Arkansas, Lombardi in Brooklyn.

- Both played for legendary college teams of the 1930s: Bryant for Alabama's Rose Bowl champions and Lombardi as one of the "Seven Blocks of Granite" at Fordham. (They just missed playing against each other. Lombardi was not yet eligible when Fordham hosted Alabama at the Polo Grounds in 1933.)

- Both have a direct connection to Knute Rockne through their college coaches. Frank Thomas of Alabama played QB for Notre Dame, while Jim Crowley of Fordham was one of the Four Horsemen.

- Both coached at schools with military traditions. Lombardi was an assistant under Earl Blaik at West Point while Bryant was head coach at Texas A&M when all male students were part of the ROTC Corps.

- Each earned his first national title in 1961, when Alabama was #1 in the final AP Poll and the Green Bay Packers won the NFL Championship.

- Both had to discipline star players. Bryant suspended QB Joe Namath for the 1964 Sugar Bowl. Paul Hornung, Packers RB, was suspended for a year by the NFL for betting on football.

- Both were "uncompromising taskmasters who were often accused of brutalizing their players. ... Both preferred overachieving players with 'team' skills to superathletes who were more difficult to coach."

- Both stressed defense and played conservatively on offense, emphasizing the running game.

- "Both inspired devout loyalty and affection in their players, assistants, and colleagues."

|

Vince Lombardi

Vince Lombardi |

|

The Rise of Southern Football

The title of this piece is taken from a Wall Street Journal article ? "What the Rise of Southern Football Says about America." (Thanks to Ned in BR for the December 5, 2008 article.) The writer includes some interesting facts.

- The top six states in terms of number of NFL players by percentage of the state population are Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Alabama, Florida, and Georgia.

- Northern states like Pennsylvania that have traditionally supplied numerous Division IA recruits are falling behind their Southern counterparts.

- For example, Louisiana boasts 64 natives playing in the NFL whereas Pennsylvania, with three times the population of the Bayou State, has only 44 NFL players.

- Historians point to the 1926 Rose Bowl as the spark that lit a football fire that spread across the South. In that game, Alabama upset Washington.

- One individual affected by the game was 12-year-old Paul Bryant, who listened to the national broadcast of the game on NBC. The Bear later said: "I never imagined anything could be that exciting. I still didn't have much of an idea of what football was, but after listening to that game, I had it in my mind that what I wanted to do with my life was go to Alabama and play in the Rose Bowl ..."

- With no major league baseball teams below St. Louis, the South rallied around football because it offered a way for their young men to compete with the more prosperous North and West.

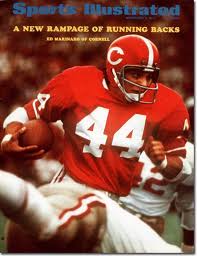

- Of course, until the 1970s the major Southern universities competed on the gridiron with white boys only. Eventually, however, "the desire to win was so strong it even outweighed racial prejudice ? Mr. Bryant was finally able to freely recruit black players after his team suffered a beating in 1970 at the hands of Southern California, whose star RB, Sam Cunningham, was black."

- "The breadth of the South's football culture creates a fanaticism that crosses all lines. People who didn't attend the schools, or go to college at all, still support them, and will even make donations."

- "College football also encourages a pride of place; something other popular sports in the south, like Nascar, don't. ... People will describe themselves as being from Alabama or Georgia even if they've worked in San Francisco for the last 20 years."

- "Within the nine SEC states, two-thirds of the governors and U.S. senators are SEC alumni. In the eight Midwestern states that make up the Big Ten, just over a third of the governors and senators went to one of their states' major football schools."

- Football is crucial to the financial health of most of the large universities in the south. "Their average undergraduate enrollment of roughly 18,000 is significantly smaller than the averages for the Big 12 and Pac-10 conferences. The median household income in Ohio, the poorest state represented by the Big Ten, was $4,500 higher than the average median income for all the SEC states last year."

- "Nonetheless, in 2006, four SEC schools ? Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and LSU ? raised $35 million or more in athletic donations. ... That figure beats every school in the Big 12, Big East and Pac-10 that responded to the survey."

- "The historical knock on the SEC schools among rivals is that their success is predicated on a willingness to stockpile great players by violating NCAA rules on recruiting and athletic benefits."

- "Another charge is that lower academic standards give SEC teams an advantage in recruiting. Just three SEC schools ? Vanderbilt, Florida, and Georgia ? were cited among the top 80 universities in U.S. News & World Report's 2009 college rankings, while all 11 members of the Big Ten were in the top 80."

Read a Biased Opinion from this site on this topic.

|

|

From Homeless to the NFL

Brennan Marion, WR for the Tulsa Golden Hurricane, was signed as a free agent by the Miami Dolphins after the 2009 NFL Draft. What's so significant about that, you say? Well, Marion's road to the NFL was circuitous to say the least.

- Marion attended a different school in the Pittsburgh area each year from grades six to twelve because his mother moved frequently.

- He moved to the San Francisco area following his senior year of high school in order to play for De Anza Junior College with his best friend, Chuck Thompson.

- Despite working odd jobs to make ends meet, he and Thompson could not keep up with the $1,300 montly rent on their apartment and were evicted. (Sounds like they selected much too expensive digs.)

- With no place else to stay, they slept in the school's locker room when the janitor left the door unlocked and in the press box when he didn't. They ate the value meals at McDonald's and Wendy's and cookies and chips given them by a clerk at the 7-Eleven.

- After three months, an assistant coach finally figured out what they were doing and invited them to live with his family.

- Despite the challenging living conditions, Marion led all California JC players in receiving to earn a scholarship to Tulsa.

- With room and board paid for and access to Division IA workout facilities, Marion gained 30 pounds and improved his speed to 4.3 for the 40. The next two seasons, he caught 82 passes for 2,356 yards, averaging 31.9 per catch as a junior, an NCAA record.

- Brennan's Cinderella story received a setback when he tore his ACL in the 2008 C-USA championship game. That caused NFL teams to back off him in the draft.

- He was still limping at the Dolphins' minicamp but said his knee was 90%. He ran a 4.52 40 just three months after surgery. He has a chance to at least make the Miami practice squad.

|

Brennan Marion |

|

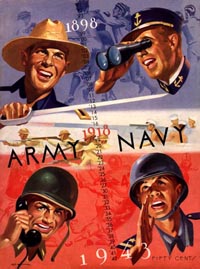

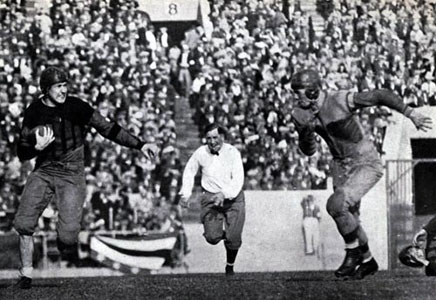

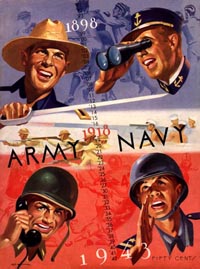

When Army Sang "Anchors Aweigh"

Captains meet before the 1942 Army-Navy Game

Earl Blaik

|

World War II travel restrictions made the 1942 and 1943 Army-Navy gridiron clashes unique.

- 1942: After playing the annual classic at Philadelphia every year since 1932, the service academies played at Thompson Stadium in Annapolis for the first time since 1893. Congress actually debated whether the game should be cancelled because of the war. However, President Franklin Roosevelt, just as he did for major league baseball, decreed that the game should be played because it would be good for the morale of the military and of the nation. Because of gasoline rationing, attendance was limited to those within a 10-mile radius of the stadium. So that ruled out the West Point Cadet Corps from attending. The Naval Academy superintendant ordered third- and fourth-year midshipmen to sit behind the Army bench and cheer for the visitors. The middies sang Army fight songs and yelled Cadet cheers during the game, led by two Navy cheerleaders who had traveled to West Point to learn them. Navy won for the fourth year in a row, 14-0, before a crowd of only 11,700, the lowest for the annual clash since 1893. (Just a year before, nine days before Pearl Harbor, 98,497 had attended in Philadelphia.) With the pressure and uncertainty of the war, players let off steam on the field with crushing hits, punches to the jaw, and tripping and kicking at every chance. At one point, an Army player called time in order to find his missing teeth in the grass. Colonel Earl Blaik, in his second year rebuilding the Army football program, guided the Cadets to a 6-3 record. The win gave coach Billick Whelchel a 5-4 record for his rookie season at the helm in Annapolis.

- 1943: Army hosted at West Point for the first time since 1892. Again, a faction in the War Department lobbied for the game's cancellation, and it was only nine days before the scheduled date that the go-ahead was given. The situation was reversed from 1942 as part of the cadet corps served as Navy's rooting section. The cadets sang "Anchors Aweigh" with as much enthusiasm as the midshipmen had sung "On, Brave Old Army Team" the year before. The result was the same, however ? another Navy victory, another shutout, 13-0, and another physical game. Five fights had to be broken up in the first half alone. Army did improve its record slightly from 1942 to 7-2-1 to rank #11 in the final AP poll. Navy, at 8-1, finished #4. The only loss was to national champion Notre Dame.

- 1944: The annual spectacle returned to a neutral site, Baltimore, never to be played again at either Annapolis or West Point. With Felix "Doc" Blanchard's transfer to West Point from North Carolina, Blaik had all the pieces in place for the greatest Army teams of all time. The 1944 and 1945 aggregations, with Blanchard joining Glenn Davis as "The Touchdown Twins," each went 9-0 and were acclaimed national champions. Army ended Navy's five-game winning streak with a 23-7 win, then triumphed again, 32-13, at Philadelphia in 1945. After the '45 season, Blaik turned down an invitation to the Rose Bowl, feeling his team had nothing left to prove and not wanting to interfere with players' exam preparation and holiday leave.

|

|

|

Football Players on TV

Bill Cosby

|

Here are some former football players who had continuing roles in TV shows.

- Bill Cosby averaged 3.5 yards per carry on 36 attempts for the Temple Owls in 1961. Starting in 1965, he won the Emmy for best actor in a drama series three straight years for I Spy. Later, The Cosby Show, which debuted in 1984, was the #1-rated TV program four years in a row.

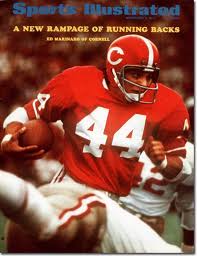

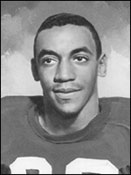

- Ed Marinaro finished second in the Heisman balloting in 1971 after setting 16 records as an RB at Cornell. He led the nation in rushing in both 1970 and 1971, becoming the first back to amass over 4,000 yards. He played six years in the NFL with the Minnesota, New York Jets, and Seattle. After one season in a support role on Laverne and Shirley, he starred in the police drama Hill Street Blues from 1981-6.

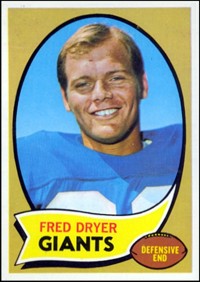

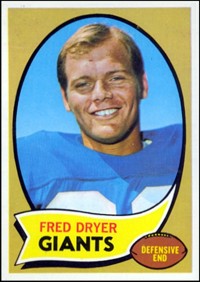

- Fred Dryer played a solid DE for the Los Angeles Rams and New York Giants (1969-81), making the Pro Bowl in 1976. He is the only player in NFL history to record two safeties in one game (October 21, 1973). Dryer starred in the police drama Hunter from 1984-91.

- Mark Harmon, son of Heisman trophy winner Tom Harmon, started at QB for UCLA (1972-3). He started acting right out of college, usually playing law enforcement and medical roles. In 1980, he finally landed a starring role in the series St. Elsewhere and later was in Chicago Hope. His most famous role is the one he still enjoys as the lead on NCIS.

Reference: Football's Most Wanted, Floyd Conner

|

Ed Marinaro

>Mark Harmon

|

|

|

Political Players

Gerald Ford

Jack Kemp

|

These men had success on the gridiron and then in the political arena.

- Undoubtedly the most athletic president ever was Gerald Ford. He was the starting C for Michigan from 1932-4. He played in the 1935 College All Star Game against the NFL champion Chicago Bears. He was so good that Sports Illustrated named him to its Silver Anniversary Team in 1959. He turned down NFL offers in order to attend Yale Law School where he served as an assistant coach. After serving 24 years in the House of Representatives, Ford became vice president in time to replace Richard Nixon when he resigned.

- Dwight Eisenhower played HB at West Point in 1912, earning the nickname the "Kansas Cyclone." He suffered a knee injury late in the season that ended his gridiron career. (The injury occurred against Tufts the week after Army lost to Carlisle and the great Jim Thorpe. It did not happen while trying to tackle Thorpe, as many sources report.) After a military career that culminated as Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, Ike was elected president in 1952 and served two full terms.

- Jack Kemp played QB for Division III Occidental College (CA) and then in the NFL, CFL, and AFL. He led the Buffalo Bills to the AFL championship in 1964 and 1965. He finished with 21,218 passing yards and 114 TD tosses. He started his political career, in a sense, while still a player when he co-founded the AFL Players Association. He was elected to Congress in 1971, serving nine terms. He became Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under George H. W. Bush. He ran unsuccessfully for vice-president on the Republican ticket of Bob Dole in 1996.

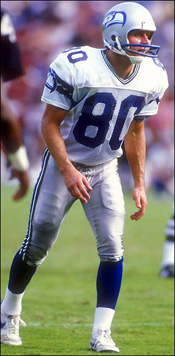

- Another outstanding pro player who entered politics is Steve Largent. After a successful college career at Tulsa, he played WR for Seattle from 1976-89, setting career records for receptions (819), yardage (13,089), and TDs (100), all since surpassed by Jerry Rice. He represented Oklahoma in the House of Representatives from 1994 to 2002, when he ran unsuccessfully for governor.

Reference: Football's Most Wanted, Floyd Conner

|

Dwight Eisenhower

Steve Largent

|

|

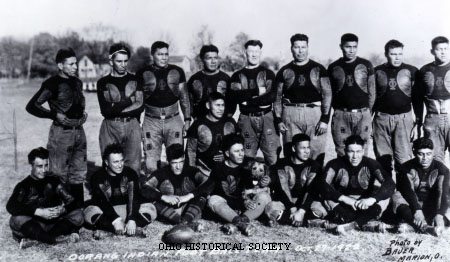

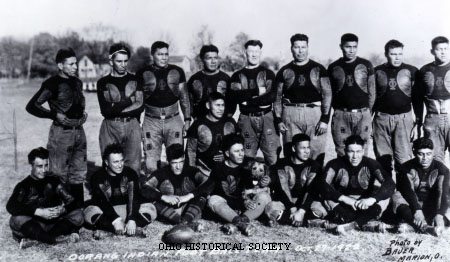

Weirdest Team in NFL History

Without doubt, the most unusual team in NFL history was one of its first, the Oorang Indians, who competed in the 1922 and 1923 seasons. If you're searching your mental geography database to decide where "Oorang" is, stop. The team was not named for a city, as we will now explain.

Oorang Indians of the NFL

Oorang Indians of the NFL

|

- The team was the bright idea of Walter Lingo, owner of the Oorang Dog Kennels in LaRuse, a small OH town. Lingo, who had no interest in football, paid the $100 fee to obtain a franchise in order to create a team that would promote the owner's mail order dog business.

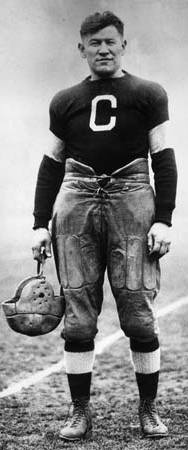

- Walter hired the man he called "the world's greatest athlete," Jim Thorpe, to assemble a team composed entirely of Native Americans.

- The Oorang roster included players with names like Big Bear, Dick Deer Slayer, Long Time Sleep, Joe Little Twig, and Laughing Gas. There were also Leon Boutwell, Bob Hill, and other players with American names. Although there were charges that Thorpe played some ringers, apparently every player had at least some Indian blood. Most of the squad members came from Thorpe's alma mater, Carlisle Indian School.

- The team was the only all-Indian team ever to play in a major pro league.

- The team could not play its home games in Larue for the simple reason that the town had no field. However, only 15 miles away was Marion, a city of 30,000 which did have a suitable field. Marion was booming because it was the hometown of the current U.S. President, Warren Harding.

- The 1922 team played only one home eague game, defeating the Columbus Panhandles in the second league contest 20-6 before 1,200 at Lincoln Park in Marion. They did host Bucyrus, an independent team, the next week and beat them by the same score, although the contest didn't count in league standings. The Indians finished the season 3-6 in league games and 5-8 in all games.

- Oorang didn't do well for several reasons.

- It was hard for the team to take football seriously when the owner was much more interested in the pregame and halftime activities than the game itself. Lingo produced elaborate exhibitions involving his Airedales and Indians. For example, Nikolas Lassa wrestled the bear that was part of the show. Players also were expected to display their marksmanship, tomahawk work, and knife and lariat throwing as well as demonstrate Indian dances.

- Another reason for the team's lack of success was Thorpe himself. He was not a good coach, especially where discipline was concerned. Many players had a liquor problem that often rendered them at less than full strength for the games.

- Thorpe didn't play the first part of the season and even when he finally did play, it was seldome more than a half. One news story said that Thorpe's presence on the field improved the team by "fully 50 percent."

- The best player on the team was RB Joe Guyon, who had played at Carlisle a few years after Thorpe and also at Georgia Tech. Oorang was not his first pro team, and he ended up playing seven years in the league and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1966. He led the 1922 Indians in yardage and points.

- The bottom fell out for Oorang in 1923. The Indians went 1-10 in NFL games and beat the Marion Athletic Club in a non-league game that was their only home contest of the season. Oorang became a "travelling team" that played all its games on the road, a common occurence in pro football in the 1920s. The only NFL victory for Oorang was in its final game, 19-0 over the Louisville Brecks at the Kentucky Fair Grounds. It is little wonder that Louisville never fielded another team in the NFL after that debacle.

- One problem was that injuries kept Guyon out of action until the eighth game. Thorpe played much more than he did the prevous year but was himself the victim of an injury in the ninth game. Reporters agreed that, when healthy, Thorpe "was still a strong punter, passer and line-plunger but had lost the blazing speed that had made him a great player." The other good player on the squad, B-E Pete Calac, was the only one of the Big Three to play most of the season.

- Crowds for Lingo's dog and pony show (literally) were down from the previous season. The novelty had worn off although bad weather was the culprit on some occasions. So, faced with diminishing returns on his investment in a football team, Walter threw in the towel and the Oorang Indians were history.

|

|

|

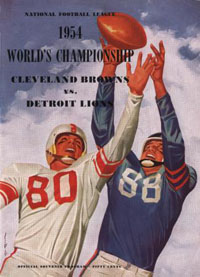

NFL Fumbled Earlier Chances before '58

1958 NFL Championship Game between the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants catapulted the NFL to national popularity. The first OT contest in football history captured the nation's imagination. However, the league might have gained national prominence earlier if previous title games had been more tightly contested.

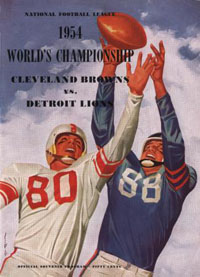

- 1953: Let's start with this season because the championship game was the last close one for five years. The Detroit Lions edged the Cleveland Browns 17-16 at Briggs Stadium in Detroit. However, only 50% of American homes had TV sets. Furthermore, neither team was from a "glamor" city like New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles. For the third year in a row, the game was telecast on the DuMont Network rather than on NBC or CBS, the major TV players.

- 1954: The Browns annihilated the Lions in a rematch 56-10 in Cleveland's Municipal Stadium. (The championship game alternated between the Western Champion and the Eastern Champion cities. Regular season records and head-to-head competition made no difference in determining the host team.) With the score 35-10 at the half, most viewers of the DuMont broadcast tuned out.

- 1955: Another blowout - Cleveland 38, Los Angeles Rams 14. NBC telecast the action for the first of nine straight years. The crowd at the LA Coliseum was 85,693, by far the largest attendance for the title game by 17,000. The contest was still competitive at the half, with the Browns leading 17-7. However, 14 unanswered points in Q3 made it 31-7 heading into Q4. That sound you heard was TV sets across the nation changing the channel.

- 1956: The final game matched the Giants and Bears, storied franchises in two of the largest cities in the nation. However, any momentum the NFL might have gained dissipated when New York raced to a 34-7 halftime lead on their way to a 47-7 romp.

- 1957: Cleveland and Detroit met for the championship for the fourth time in six years. (Yawn!) The Lions gained revenge for their 1954 whipping in Cleveland: 56-10. (Double yawn!) Not a game to excite fans who were not NFL regulars.

Finally, in 1958, all the pieces fell into place.

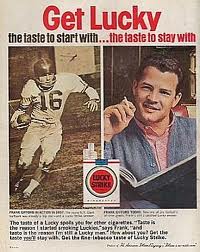

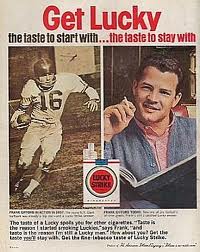

- The glamorous Giants, the Yankees of the NFL with many of its players like Frank Gifford, Charley Conerly, and Kyle Rote appearing in TV and print ads from the media capital of the world, faced the upstart Baltimore Colts, the darling of fans who like to root for the little guy against the big city bully.

- The game showcased pro football at its best. The #1 defensive team in the league, the Giants, against the top offensive club, the Colts. Both teams employed interesting, balanced attacks with excellent passing and running.

- The NFL had its first riveting contest heading into Q4 in five years. Then luck produced the Colts' last minute drive for the tying FG to force the first OT in football history. Almost overnight, the NFL became the most formidable force in sports.

- Another key factor was the accession of media-savvy Pete Rozelle to the office of commissioner in 1960. Pete parlayed the success of the '58 title game into bigger TV contracts, which meant more money to put an even better product on the field. Pro football soon passed up baseball and college football in popularity and has never looked back.

|

Frank Gifford in a print ad

Charley Conerly, Marlboro Man

|

|

|

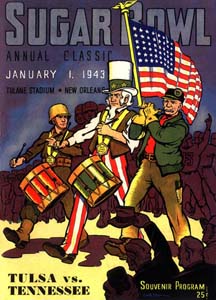

Sugar Bowl Travel Restrictions

|

|

New Orleans Times Picayune 12/14/1942

Approximately 16,000 Sugar Bowl tickets have been returned here by Tulsa and Tennessee universities in deference to the office of defense transportation's request that bowl authorities recall all tickets sold outside of the New Orleans area.

A. B. Nicholls, VP of the football spectacle's governing committee, told Monday Quarterbacks that these tickets were now on sale to the locals and that they would be distributed on a "first-come-first-served" basis. Nicholls stated also that the transportation of all athletic teams to New Orleans including participants in basketball and boxing, seemed assured.

"I know that arrangements have been completed to bring the Great Lakes and Stanford basketball teams here," he said. "And there seems no difficulty in the way of either Tulsa or Tennessee ."

Thousands of the returned Sugar Bowl tickets were distributed to service personnel. The Volunteers of General Robert Neyland defeated Henry Frnka's Golden Hurricane 14-7 before 58,361 on New Year's Day 1943.

|

|

|

1926 Rules Changes

These rules changes were in force for the 1926 college football season.

- After a safety, the ball is put in play from the 20 yd line by kick. A lateral pass before the kick is not allowed.

- If the kickoff team kicks out of bounds twice in succession, the receiving team gets the ball on their own 40.

- Hand proctectors and masks for injured players are allowed again for the first time since 1922. All padding is subject to inspection by the umpire.

- The end of each quarter is denoted by the head linesman's gun. Previously, the gun was fired only at the end of each half.

- A free kick must go at least ten yards. The kicking team is entitled to a second try.

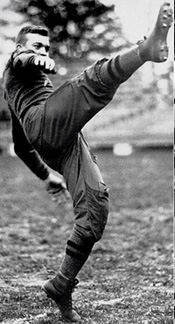

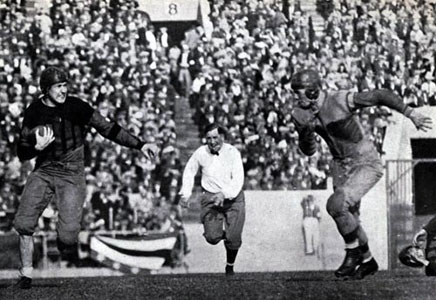

Johnny Mack Brown running for Alabama against Washington in the 1926 Rose Bowl.

Johnny Mack Brown running for Alabama against Washington in the 1926 Rose Bowl. |

|

|