February 11, 2023

|

Quotation

|

|

Tiger Den Basketball

LSU Post-Season Games - 1986 Part 4 The Tigers advanced to the Southeast Regional in Atlanta where they faced Georgia Tech in their home city. |

|

NBA Finals - Game 7: 2005 |

|

Who was the youngest player to win the NBA finals MVP award?

|

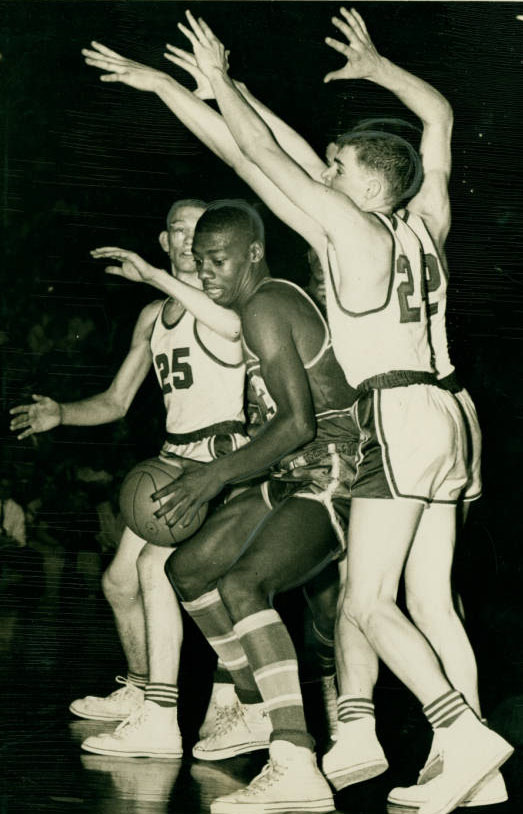

Recruiting Oscar Robertson - 3

The Big O: My Life, My Times, My Game, Oscar Robertson (2003)

As the Indiana Star of Stars in 1956, Oscar was the most sought-after player in the country. Read Part 1 | Read Part 2 A novelty salesman working out of Cincinnati by the name of Al Hutchinson was a major fan of the University of Cincinnati's basketball team. By chance he also had seen me play during my sophomore year at Crispus Attucks. Al was the first man to tell Cincinnati coach George Smith that he had to see the Attucks team. Smith went down to see what Willie Merriweather could do on a court, but he left interested in me. During my senior year, I was at the top of his list of students to recruit, but somehow Cincinnati's pitch hadn't made such a huge impression on me.

It was late March, awfully late to be thinking about recruiting for September enrollment, when a conversation took place in George Smith's office. Dick Forbes, a sports columnist for The Cincinnati Enquirer, was talking with Tom Eicher, UC's sports publicity man. Walter Paul, an executive for Queen City Barrel and Astro Container of Cincinnati, was also there. Paul recruited for the University of Cincinnati's basketball program, partly as a hobby, and partly because they had such a limited coaching staff. Walter Paul sat in the office, listening, as the reporter and the sports publicity man talked back and forth about me. One of them said, "I bet this guy couldn't be had for less than $10,000."

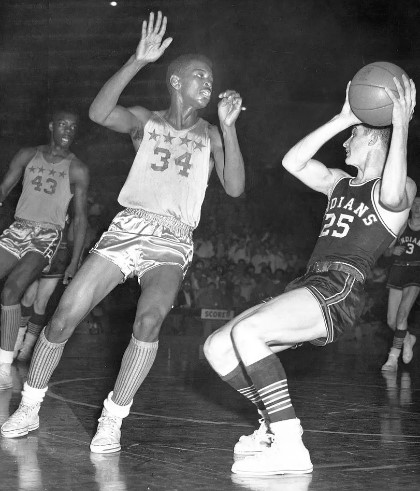

Oscar Robertson (43) playing for Crispus Attucks. This was the first time Walter Paul ever heard of me. Years later he told me, "That comment triggered me. You know, you sustain a certain motivation all through life. But there are some things you want worse than anything else. That–and convincing the woman I married–were the two things that I worked hardest at in my lifetime over a short period of time."

Without George Smith knowing a thing about it, Walter Paul went out on his own, trying to find out how to learn about me.

He started out by talking to the black truck drivers who worked for him and then going into Kingan's, the meat-packing plant where my dad used to work in Indianapolis. The workers there told him that my father would have very little influence on me. Then he found a meat inspector who said he knew my minister. That too was a blind alley. Finally, via the process of elimination, he determined that the key people in my life were Ray Crowe and my mom. Later, both Ray and my mom told me that neither one of them felt they had a hold of me. Each suspected that the other one had control. George Smith thought it was my mom who was the major factor in my decision as to where to attend college, and said, "Nobody else in his life even came close." But in the end, as Smith and Paul found out, I was my own man.

Paul's first approach to Ray Crowe didn't get him anywhere. Next, Paul contacted my mother. "We had long discussions about the poverty, the holes in the roof, the tacky linoleum, no showers for the kids, and all that. I listened, no comments. Just listened. Then she played me some spiritual numbers that she wrote in hopes of recording. They had a great beat to them."

My mom told Walter Paul that she wanted two things. One, she wanted to get on the 50-50 Club–a midday variety show piped out of Cincinnati WLW-TV into Indianapolis, Columbus, and Dayton. Two, she wanted to get somebody with some clout to listen to that music. She wanted to try and have it published.

My mom told Paul that the apartment owner next door to us had been authorized by a wealthy Indiana University alumnus to offer the family $5,000 for my enrollment at Bloomington. But she also said that Bailey had been cold-shouldered at IU, and there was no way I would go there. Furthermore she said that I wasn't for sale. That stuff had gone out 90 years ago.

Next, Paul, with Bearcats coach George Smith in tow, visited Crispus Attucks. They wanted to talk with Principal Lane, but he was out of town, so they had a long chat with the assistant principal. Not only did Paul and Coach Smith come away impressed with the cleanlliness and the atmosphere of the school, but the assistant principal gave me high marks on character, scholarship, and moral fiber. He told them that my desire to be a great player kept me out of trouble; I avoided anything off the straight and narrow, and even stayed away from teammates who were headed the wrong way.

After they got the tour of Attucks, they met me. Two or three months of intense work had gone into the project at this point. Attucks's dad was furious at him, claiming that his son had neglected the family business to run around chasing a basketball player. But finally, Attucks laid eyes on me.

It was my first time in a hotel suite. Of course I was shy, didn't say two words to the man.

Attucks and Coach Smith made their presentation. They said, "Look. You are the most-sought-after basketball player in the United States. No matter where you go, you will be looked upon skeptically. At the University of Cincinnati we have a co-op program in thebusiness administration school. We have arranged a double-section version of our regular co-op program, where you can actually go to school for 14 weeks and then work for 14 weeks and legally be paid for it and not made ineligible as an athlete. You will at Cincinnati Gas and Electric on a regular wage scale."

I sat still and stayed quiet.

To be continued ... |