|

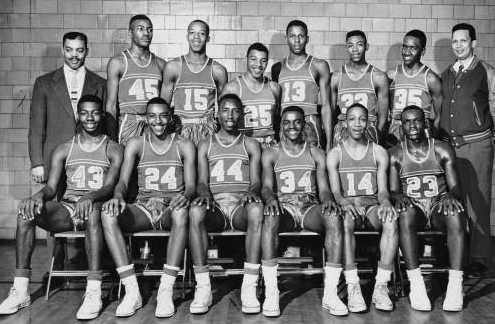

Recruiting Oscar Robertson - 1

The Big O: My Life, My Times, My Game, Oscar Robertson (2003)

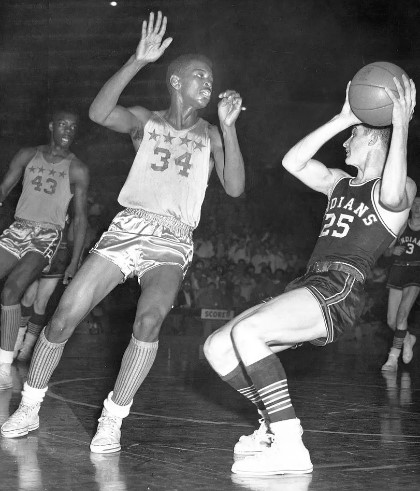

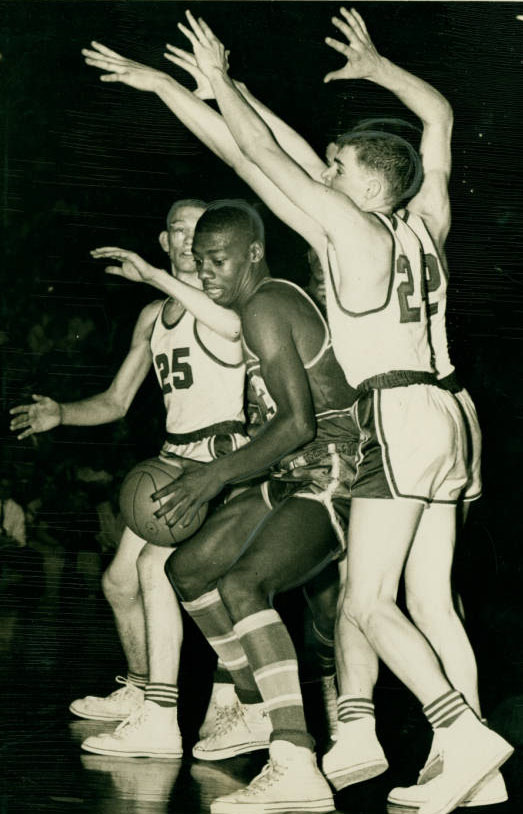

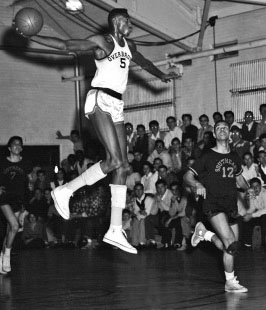

As the Indiana Star of Stars in 1956, Oscar was the most sought-after player in the country. By the time I graduated from high school, 75 colleges had recruited me, in one form or another, with at least 40 schools contacting me directly. Only Wilt Chamberlain, who had signed the previous season to play at Kansas, had received more attention. Colleges had been in touch with me since my sophomore season, but during my senior year things got crazy. Calls came to my house and school on a daily basis.

Maybe other athletes have enjoyed the recruitment process. There's a lot to enjoy: the attention, the constant praise, the promises. To some degree, everyone likes being romanced. Make that almost everybody. I wasn't at ease with the process. In fact, I was extremely cautious about it, wary of all these people I didn't know. I sa them as part of the other world, the white world, a world that had made very few sincere overtures to me. Moreover, I had heard of situations where other black players felt awkward simply because of their unfamiliarity with the way things worked. There was the story of a player who took a recruiting trip to Nebraska. On the plane he asked the stewardess how much it would cost him to have a sandwich. Well, the sandwiches were complimentary, they were the in-flight meal, and he'd never been on a plane. He didn't know. And he came back from a recruiting trip with money in his pockets to pay for his trip back home. His mom thought they were buying him like a slave and made him send all the cash back. Then there were the stories of black players, like Bill Scott who went to white schools and excelled, only to be run from the team by their teammates who thought they were being shown up.

Oscar Robertson and Wilt Chamberlain in high school I was by no means afraid of the future, but I also wasn't in any hurry to commit to anything. I started planning. I realized that where I attended college was a huge decision, and I wanted to make it carefully, on my own terms. I was going to play college ball somewhere, that was for sure, and wherever it was going to be, I allowed myself to believe that the school I would choose would celebrate greatness the same way for everyone, regardless of skin color. Maybe I was looking through rose-colored glasses, to believe there was such a place. But that's how I thought. If there were a college where merit mattered more than skin color, I'd find it. That would be where I would attend college.

NCAA rules were that colleges couldn't legally talk to me until after the Kentucky-Indiana all-star game, when my eligibility to play high school ball expired. So that bought me ome time. And once basketball ended, I was busy all spring with the track squad–I qualified for the state championships in the high jump. I also played around with the baseball team (in one game, they let me pitch, and I went the distance for the win, striking out ten, allowing only five hits). So long as I was involved with high school sports, recruiters weren't supposed to contact me. Of course, they still did. My did disconnected his phone three times. Guess all those recruiting folks didn't realize how little pull my dad had with me. Those recruiters could have become hsi best friends, and it wouldn't have affected my decision.

A publicity guy named Haskell Cohen, who worked for the NBA, wanted me to go to Duquesne. But that school turned me off when they suggested I be a bellhop at Kutsher's in the Catskills and play basketball all summer. They said it was the way to become an All-American, but I had to work in the summer, and not as a bellhop. Cohen didn't care. He spread rumors that I was virtually pledged to Duquesne. There was even a rumor that our house on Boulevard Place was part of a deal made so that I would play ball at Duquesne. I heard that I had been given a $250 watch and a wardrobe of clothes. I used to look at my wrist to see if it was true, but there was never any watch. I used to stare down at my clothes, shirts that I'd had for years and years, and laugh at my stunning wardrobe. One rumor, spread during the height of the recruiting competition, had a FOR SALE sign appearing in our yard. Absurd.

When my friend Don Brown got in some trouble with his father and couldn't drive, I drove us to school in Don's car; of course that sprarked rumors that I'd been given a car. The truth is, I didn't get my first car until after I graduated from high school, after I had made my decision, once recruiting was over. I got my first real job working for a businessman named Swanson that summer. I called him Swanney. He had a car wash and a construction crew. I worked on the crew, putting in asphalt all day long. It wasn't any harder than throwing hay into a moving wagon all day long, so I didn't mind it. Swanney told me if I worked to make my money, at the end of the summer he'd help me get a car. At the end of the summer, I had maybe three or four hundred dollars. I found a used Mercury for sale, two-tone brown, for about $500. He made up the difference, and boom, I had my first automobile.

Imagine going through your senior year of high school, trying to live a normal life while all these rumors that you're for sale to the highest bidder are flying around. Meanwhile, you're about to spend the summer putting in pavement and saving up money for a used, two-tone Mercury. Yes, people were tryig to wine and dine me. But I wasn't on the take, so there wasn't much they could give me.

Continue below ...

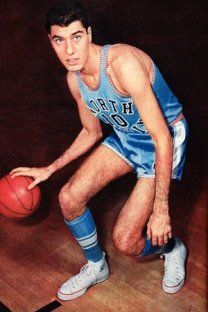

The #1 North Carolina Tar Heels hosted their archrival, the Duke Blue Devils, on February 9, 1957.

Duke led most of the game, but in the last ten minutes the Tar Heels, the nation's only major undefeated team, took the lead and began to pull away. Led by Lennie Rosenbluth's 35 points, UNC held what appeared to be a comfortable 73-65 advantage with two minutes to play. But four Blue Devil free throws cut it to 73-69 with 45 seconds play.

That's when Duke's Bobby Joe Harris began his thievery. He twice stole the ball from Tommy Kearns and fed fellow G Bob Vernon for layups to tie the score with 24 seconds to play.

And then Harris went from hero to goat.

The hand-operated scoreboard at Woollen Gym (built in 1937) didn't immediately record the last Duke basket. Harris looked at the scoreboard and saw that Duke was trailing by two. Even if there had been a shot clock in those days, there was too little time left to wait for UNC to shoot. So Harris fouled Kearns while trying to steal the ball in order to stop the clock.

As Kearns headed for the foul line, Harris glanced again and saw the adjusted score. "What have I done?" Bobby Joe muttered. Kearns sank both shots with 16 seconds left. Duke had time to tie but couldn't make a basket.

Years later, Harris admitted: "It still bothers me. What a terrible way to lose a game."

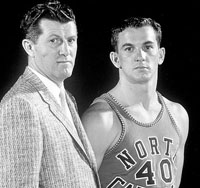

L-R: Lennie Rosenbluth, Bobby Joe Harris, Frank McGuire and Tommy Kearns Bobby Joe got a measure of revenge the next time the Devils visited Chapel Hill. #13 Duke upset Frank McGuire's defending national champions, 91-75.

Trailing 36-35 at halftime, the Blue Devils played an almost perfect second half to outscore the #7 Tar Heels 56-39.

Harris called a timeout with a few seconds left with the game well in hand. Coach Howard Bradley demanded to know what he was doing. Bobby Joe replied: "Well, Coach, I just wanted to give them time to get the score right. They've rubbed our noses in it long enough."

The team sat quietly on the bench and waited out the timeout without Bradley saying another word.

Reference: Tales from the Duke Blue Devils Hardwood, Jim Sumner (2005)

John Wooden's UCLA Bruins had won six NCAA championships in a row when they came to New Orleans in December 1972 to play in the Sugar Bowl Basketball Tournament. The 1972-73 edition of the West Coast juggernaut had won their first six games of the season by a minimum of 16 points. That stretched the Bruins' winning streak to 51 games. The undisputed leader of the Bruins was 6'11" C Bill Walton, who brought an average of 19 points and 17 rebounds into the tournament. Harv Schmidt, coach of Illinois, one of the other three participants, said, "Walton is one of the best power postmen to ever play the college game."

Joining Walton in the starting lineup were forwards Keith Wilkes (6'6") and Larry Farmer (6'5") and guards Tommy Curtis (5'10") and Larry Hollyfield (6'5"). Assistant coach Gary Cunningham, speaking for Coach Wooden, said, "The Sugar Bowl has a strong field ... we're looking forward to the competition."

UCLA played Drake in the opening game at the Municipal Auditorium Friday, December 29, with the Illini facing Temple in the nightcap.

Drake coach Howard Stacey was under no illusion about his team's chances. "No doubt UCLA is in a class by itself. ... We are probably a lot like UCLA in philosophy. We'll try full court pressure on defense, and we believe in the fast break offensively." His squad entered the contest with a 6-1 mark, including the most recent victory over Iowa 96-80. The lone setback came at the hands of Iowa State 88-84. All five Bulldog starters averaged in double figures with 6-2 G David Langston the leader with 18 ppg.

As expected, UCLA jumped out to an early lead before a crowd of over 7,000 that shoe-horned into the 1930-vintage arena. The Bruins led 32-24 after 12 minutes of play. But Drake started converting a rash of UCLA turnovers - 16 in the first half alone - into points. The 18-6 run that carried into the second half propelled the Des Moines school into a 38-34 halftime lead and a 42-38 margin in the early minutes of the second half.

The underdogs benefitted from Coach Stacey's strategy of moving his center, 6'8" Larry Seger, to the top of the key to draw the intimidating Walton out of the middle. Seger canned five buckets on long, looping set shots from 20 to 28'.

After Wooden made some halftime adjustments, including switching Walton off Seger, the Bruins began firing on all cylinders. Farmer and Walton scored the first 13 points in the second half to build up a 10-point lead. The Bulldogs got no closer than eight points after the first five minutes of the half.

Walton, who led all scorers with 29, simply overpowered Seger underneath. UCLA shot an incredible 63.5% from the floor thanks to numerous layups on the back end of steals and Walton's point blank baskets. (Dunking was prohibited by the NCAA from 1967-76.)

The final margin was 85-72. At least Drake had the satisfaction of holding the mighty Bruins to their smallest margin of victory so far in the season.

Stacey was asked what it would take to stop the agile, strong Walton. "Another Walton. He is the best center I've seen in a long time, and the best I've every coached against ... including Jerry Lucas. UCLA ... kept the pressure on us and waited for the mistakes even though we stayed with them."

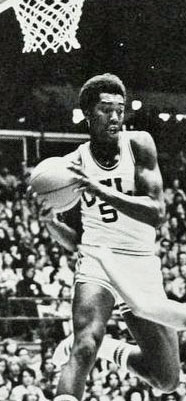

L-R: John Wooden and Bill Walton, Larry Farmer, Nick Weatherspoon Illinois defeated Temple 82-77 to run their record to 6-2 and earn the right to play UCLA for the championship the Saturday afternoon.

G Jeff Dawson's 24 points and F Nick Weatherspoon's 22 accounted for over half of the Illini's points. Could the duo continue that production against the Bruins?

'Spoon scored 18, but Dawson was held to 14 as the methodical Uclans prevailed 71-64.

The #1 Bruins didn't have an easy time of it but at no time did they not seem in control of the game. However, they trailed ten minutes deep into the game before pulling ahead 37-31 at intermission.

Nick Conner, Illinois' cat-quick 6'8" C and a Connie Hawkins look-alike, made Walton work at both ends of the court. After scoring just 10 the first 20 minutes, Bill put in 12 the second half to again lead all scorers and win the MVP award.

Bruins playmaker Tommy Curtis picked up three fouls in the first ten minutes of action and sat out the rest of the half. UCLA led 37-31 at the break.

UCLA got its patented fast-break working the second half and built up 53-37 lead in the first six minutes. The Fighting llini lived up to their name but got no closer than the final margin.

Wooden: "I wasn't particularly pleased with our play, but I'm much happier than I was after Friday's game. It was Illinois' pressure which caused our mistakes ... They weren't mistakes of our own. They played a fine pressure defense. Their aggressiveness caused the trouble. ... Conner, as far as I'm concerned, is the most outstanding individual we've played this year."

UCLA finished the 1971-72 season 30-0 for their seventh straight national championship. They would extend their winning streak to 88 before losing to Notre Dame in January, 1973.

1972-73 UCLA Bruins after winning their 7th straight national championship |

|