|

|

Basketball

Snapshots - 11

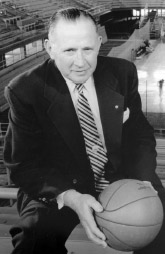

Born in 1917, Arnold Auerbach grew up in a Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn.

- Because of his hair, he early acquired the nickname "Red" that stayed with him long after he went bald and gray.

- He made the varsity basketball team in high school. 5'9" and not particularly quick, he made his mark with smart, hard, and even pugnacious play.

- He caught the eye of George Washington coach Bill Reinhart, who offered him a scholarship in the hope that Auerbach would bring some city toughness to his team.

- For his senior year, Red was voted team captain.

- After two years as a high school basketball coach, he joined the Navy during World War II, remaining stateside throughout his enlistment.

- Because he had been a coach, he ran an intramural basketball program at a Norfolk naval station that brought him into contact with players from all over the country.

After discharge in the spring of 1946, Auerbach prepared to return to his old job until he noticed an item in the newspaper that would change his life permanently.

- The general manager of Madison Square Garden in New York, Ned Irish, invited men from various cities in the northeast to discuss the founding of a basketball league to capitalize on the public appetite for sporting events after the war's end.

- As a result, eleven franchises formed the Basketball Association of America (BAA) to start play in the fall of 1946.

- Auerbach thought the league had a chance since college basketball drew well. Fans would want to see the college stars continue their career as pros just as they did in football.

- 28 years old with a wife and new baby, Red decided to take a chance. He returned to the Nation's Capital and offered himself to Mike Uline as the coach of Mike's new BAA team, the Capitols.

- Citing his military experience, Red promised to put together a talented, relatively inexpensive team of ex-navy men who brought complementary strengths for various parts of the country: backcourt players from New York, speed from the Midwest, rebounders from the West Coach.

- Impressed, Uline offered Auerbach a one-year contract for $5,000.

Since no one in the new league - coaches, players, and referees - had heard of him, Red adopted a new persona. As John Taylor has written:

He turned himself into a courtside presence that everyone in the league would be forced to contend with. During games he did not so much feign rage as he allowed it to engulf him. He pounded his fists together so angrily that his knuckles became swollen, and so he began rolling up a program before each game and using it smack his hand. He snarled at the opposing team's fans, shook his fist, sighed, waved his cigar, smacked him hand with his rolled-up program.

Amazingly, it worked.

- The Washington Capitols finished the regular season 49-11, with a 17-game winning streak along the way. They also led the league in what became Auerbach's trademark - defense.

- Red produced two more winning seasons in Washington, making the playoffs both times and losing to the mighty Minneapolis Lakers in the finals in 1949.

- The only fly in the ointment was that the Capitols were struggling to stay afloat, as was the entire league.

- So when Red asked Udine for a three-year contract to solidify his authority over his players, Mike refused, saying that the team might not last that long. So Auerbach quit.

|

Red Auerbach at George Washington U.

Auerbach in the Navy

|

Red wasn't out of work long.

- Ben Kerner, owner of the Tri-Cities Blackhawks (later the St. Louis Hawks), hired him and promised complete autonomy.

- Making more than two dozen trades, Red cleaned house until only three of the players he inherited remained with the team by the end of the season. But the Blackhawks made the playoffs.

- When Kerner, despite his promise, traded a player over Red's objection, Auerbach quit.

- So Red carried a reputation into the job market of a coach who had alienated two owners but who produced winning teams.

Once again, Auerbach got a break.

- The Boston Celtics needed a coach after Alvin "Doggie" Julian resigned to return to college ball just a month before the draft.

- Owner Walter Brown, whose real passion was hockey, didn't know whom to turn to. So he had his PR man call a meeting of local sports reporters to get their advice - an unprecedented action in pro or amateur athletics.

- One reporter suggested Auerbach, whose teams had impressed the scribe. Others chimed in favorably, saying that Red's teams played hard and never gave up.

- Before Brown could pursue Auerbach, he had to solve a crisis. The board of the corporation that owned the Boston Garden (of which Brown was GM) as well as the Celtics, after four years of losses reaching nearly a half-million dollars, voted to fold the team.

- Although the team had yet to have a winning season, Brown still felt the club would ultimately succeed. So he bought the club himself. His friends and even his wife thought the stubborn Irishman was making a huge mistake.

- One of the conditions the board had imposed before agreeing to relinquish the team was that Brown find a partner to help him survive the near-term losses. The man Walter approached, Lou Pieri, agreed to buy in on one condition: "Get Red Auerbach as your coach, and I'm your partner."

So Brown offered Red $10,000 for one year and promised to back his decisions to improve the team.

- "If we're still in business next year, we can talk about raises then," Walter said.

- Red's response: "How the hell can you say no to a man like that?"

Continued below ...

Reference: The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball, John Taylor (2005)

|

Red Auerbach 1950

Walter Brown

|

Bill Russell age 5 Monroe LA

Bill Russell

Brick Swegle

Phil Woolpert

K. C. Jones

Bob McKeen

Swede Halbrook

Tom Gola

|

Bill Russell needed a coach who believed in him and some breaks to play college basketball.

- He was born in West Monroe LA and lived there until his father moved the family to Oakland CA when Bill was nine.

- When Russell attended McClymonds High, he hadn't played any basketball. The JV coach, George Powles, invited the gangly teenager to try out.

- Bill could run and jump but had no basketball skills at all. But the coach saw potential in him and made him the 16th player on a team with only 15 uniforms. So Bill alternated suiting up with another boy. On the rare occasions that the awkward youth entered a game, the crowd cheered derisively.

- The coach paid the $2 membership fee for Bill in the Boys Club so that he could play basketball during the offseason. Going there every day after school, he improved but not enough to impress the new JV coach, who cut him.

- But Powles, who now headed the varsity, invited Bill to join his team. He demurred, figuring that if he couldn't make the JV, what chance would he have for the varsity. But the coach convinced him that he could become a good player.

- Outgrowing his clothes every four months, Russell contributed the first semester of his senior year. But he wasn't around after that to help McClymonds win the city championship because he graduated at midyear.

That might have been the end of Russell's basketball career but he got a break.

- A man named Brick Swegle formed a team called the California High School All-Stars composed of players who graduated in the middle of their senior year.

- Since McClymonds had the best team in Oakland and Bill was the only "splitter" on the team, Swegle chose him for his touring squad.

- They traveled by bus across the state playing high school and college teams. Bill had nothing to do but play, talk, and think basketball. With his analytical mind, he broke down the moves of his teammates and opponents and devised moves of his own.

- He decided that his best chance of success on the court came from concentrating on defense. Being left-handed gave him an advantage since his main hand was on the same side as the dominant hand of right-handed shooters.

- Swegle, who believed in letting players have fun with a wide open style of play, encouraged Bill to block shots aggressively. He also jumped higher than everyone else for rebounds. He began developing an acute ability to anticipate opponents' moves and quickly determine the shortest path to a rebound. Swegle was an interesting guy with a shady past. Read more about him ... (Press Ctrl-F to find "Swegle" on the page.)

His play on the All-Stars attracted the attention of the University of San Francisco.

- A Dons' assistant coach, Hal DeJulio, had attended Bill's last game at McClymonds to scout another player. Bill scored 14 points, the highest total of his high school career.

- The summer after Russell played on the all star team, DeJulio invited him to try out for the USF team. After Bill played in a scrimmage with the varsity squad, head coach Phil Woolpert offered him a scholarship. Since it was the only offer he received, he took it.

- Russell received tuition, room and board, and a part-time job in the cafeteria. He majored in transportation because he had been fascinated by the trains that thundered through Monroe.

Woolpert's program ran on a shoestring budget.

- The Dons had won the 1949 NIT under Pete Newell when that tournament was just as prestigious as the NCAA's.

- Phil took over in 1950 when Newell moved to Michigan State. After three losing seasons, Woolpert's future was shaky.

- The school had no gym of its own to play in. The team practiced "in an ancient gym with cracked windows and warped floorboards."

- The Dons played their home games at the Kezar Staduim Pavilion, the San Jose Auditorium or, for high profile visitors, the Cow Palace. Some called them the "Homeless Dons."

The style of play that Woolpert coached fit Russell's potential perfectly.

- Phil eschewed what he called "jackrabbit basketball" in favor of a defensive game. He wanted to slow down opponents, force them out of their offensive patterns, and steal the ball.

- Still, Woolpert didn't know if he'd made a wise move in signing Russell. As Phil recalled in 1968: My God, the first time I did see him at a workout, I couldn't believe my eyes. He could jump - oh, how he could jump - but he was so ungainly. Still, there something about Bill then that you just couldn't ignore. He had this rare, wonderful confidence in himself. Not braggadocio, but good honest confidence. Woolpert recalled that the first thing Russell told the USF coaching staff as a freshman was, Gentlemen, I want you to know that I am going to be the University of San Francisco's next All-America.

- Freshman coach Ross Guidice spent hours each day working with Bill, teaching him how to set screens, time passes, and improve his shooting. Russ often stayed afterward to launch 500 left-handed hook shots and 500 right-handed hook shots.

- Russell was assigned a room with K. C. Jones, a shy sophomore G who quickly became Bill's best friend because of their common interest in basketball. They analyzed all aspects of the game, jumping, dribbling, rebounding, shooting. They analyzed other players' weaknesses and ways to exploit them. They invented plays.

- Arriving at USF at 6-5 and 158 lbs, Russell continued to grow. When he moved up to the varsity a year later, he stood 6-9, making him one of the tallest players in the West Coast Athletic Conference. Woolpert later said: When Bill Russell registered for his first basketball practice, I gave him only one instruction: "Grow to seven feet and you'll be unbeatable." He did and he was. I'm a coaching genius.

Like his coach, Bill focused on defensive strategy.

- He guarded the other C but developed "smart feet" to move quickly to cover the basket if one of the opposing forwards broke free from his defender.

- He got a chance to showcase his new skills in the very first game of the 1953-4 season against California, which had clobbered the Dons 64-33 the year before. Bill was matched against all-American C Bob McKeen. A few minutes in, Bill blocked McKeen's first shot, knocking the ball into the third row for good measure. Newell, who now coached the Golden Bears, asked on the bench Where in the world did he come from? Russ blocked 13 shots, scored 23, and held McKeen to 14 as USF pulled away in Q4 to win 51-33.

- The Dons' hopes for an outstanding season nose-dived when Jones collapsed the next night with a ruptured appendix, putting him out for the season.

- They still finished 14-7 as Russell led them in scoring (19.2) and rebounding (also 19.2).

When Jones returned for the '54-55 season, he was still a junior in eligibility, meaning that he would continue to team with his pal Bill for two more years.

- One of the most integrated teams in the country with three black starters and three more as substitutes, USF won their first two games in 1954-5, lost to UCLA, then didn't lose another game for the remaining two seasons of Russell's eligibility.

- Unranked at the beginning of the year, the Dons entered the AP poll after five games and steadily moved up until they reached the top February 8 and stayed there the rest of the regular season. They caught the nation's attention during the Christmas holidays when they won the All-College Tournament in Oklahoma City where reporters from other parts of the country got to see Russell in action. Bill made the AP All-American team, totaling the third most points in the voting behind Tom Gola of LaSalle and Robin Freeman of Ohio State.

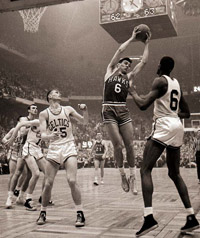

Since they easily won the West Coast conference, USF made the 24-team NCAA field.

- However, they didn't earn one of the eight first round byes, showing that the NCAA Committee harbored some skepticism.

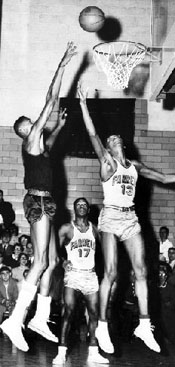

- After clobbering West Texas State 89-66 in the opening round, the Dons faced Oregon State in the Beavers' gym named for their legendary coach "Slats" Gill. OSU boasted 7-3 Wade "Swede" Halbrook, the country's tallest player.

Photographers had Halbrook and Russell pose together. Halbrook raised his right arm, a ball in his hand, as high as he could. Russell's wingspan, which had never been measured, was said to exceed seven feet, and though he was six inches shorter than Halbrook, he now raised his arm up over the ball Halbrook was holding and wrapped his fingers around the top of it. (John Taylor)

USF squeaked by OSU 57-56 after nearly blowing a 56-49 lead with a minute and a half to play. Bill outscored Halbrook 20-18. Read article about the game: Part I | Part II

- USF beat Colorado 62-50 behind Russell's 24 points to reach the finals against Gola's LaSalle Explorers. K. C. actually outscored Bill 24-23 as the Dons prevailed 77-63.

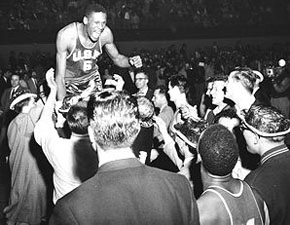

L: Woolpert and the Dons starters; R: Russell after the '55 championship game

After the season, the NCAA Rules Committee passed what instantly became known as the "Russell Rule" widening the lane from 6' to 12'.

- The change did nothing to derail the Dons Express. They started the 1955-6 season ranked #1 in the AP poll and never fell from their lofty perch, becoming the first team in the eight-year history of the poll to lead wire to wire.

- Along the way, USF made a trip to the Crescent City for a game against fellow Jesuit college Loyola. Since New Orleans was a segregated city, the Dons had some trepidation. Everyone was edgy about it, recalled Woolpert, and particularly Bill; he had been born in Louisiana. When they arrived, a local Negro restauranteur threw a banquet for the team and the press. Each player was asked to make a speech, with Russell going last. Woolpert: I was watching him as the fellows spoke. He was taking notes like crazy, and I was pretty worried about what he might say. Finally, he stood up and he was impassive as a sphinx. He looked around the table, and then he said, "Ladies and gentlemen, the greatest place to be from in America is New Orleans ..." and he went on from there to do a masterful job. Humorous and easygoing. No one could have defused a situation like that the way Bill did.

- The integrated crowd of 5,500, including a 14-year-old boy and his older brother, watched in awe as Russell swatted balls into the stands in leading the visitors to a 31-12 halftime lead. After Woolpert mercifully began substituting, the Wolfpack made the final score a more respectable 61-43. Russell scored 20. There were no incidents during the game nor any booing of players, black or white. At one point when Bill brought down a rebound, two Loyola players fell hard. He helped them up to the delight of the crowd. Read about the game.

- The Dons had an easier time in the NCAA tournament than in '55. They drew a first round bye, then rolled over UCLA (72-61), Utah (92-77), SMU (86-68), and Iowa (83-71) to run their NCAA record winning streak to 55 games and become the first team to win back-to-back NCAA titles. (The winning streak finally ended after five games of the '56-7 campaign.)

Through his four years at USF, Russell had a thorny relationship with his head coach. In his 1966 book Go Up for Glory, Bill wrote:

I was not fond of Woolpert as a coach, but I liked him as a man - sometimes. ... But though I gained my first fame with him, I could never be close to him as a man. I was a good basketball player. There were some who said I was great. Woolpert never said anything ... It never hurts to say a good word for your player. It hurt me plenty that Woolpert didn't.

Phil responded like this: In those days I wasn't about to help give Bill an inflated sense of his own importance. As a sophomore, he was a lazy player; I kicked him out of the gym many, many times for loafing during drills. When he was a junior, there were a few problems; when he was a senior, none that I recall.

Boston owner Walter Brown, at the behest of his coach, Red Auerbach, did some maneuvering to put the Celtics in position to draft Russell with the second pick. Read more ...

Bill's NBA career got a delayed start because he played for the U.S. Olympic team in Melbourne, Australia, in December 1956. Read more ...

Continued below...

|

Red, Bill, and Wilt - III

Unlike Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain lived in the spotlight from his freshman year of high school.

- 2 1/2 years younger than the man who would be his professional nemesis, Chamberlain grew up in Philadelphia in a family of nine children. A frail child, Wilton nearly died of pneumonia that caused him to miss a whole year of school.

- At first, he wasn't interested in basketball because he thought it was a game for sissies. Instead, track and field was his sport. He high jumped 6'6", ran the 440 in 49.0 seconds, the 880 in 1:58.3, put the shot 53' 4", and broad jumped 22'.

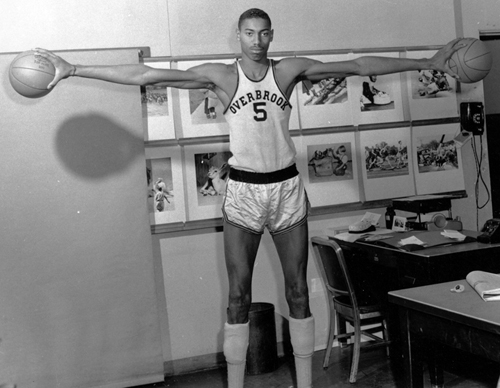

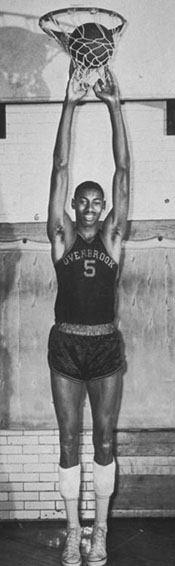

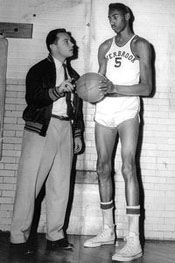

- Because basketball was king in the City of Brotherly Love and because he grew to 6'11" by the time he entered Overbrook High School as a freshman, Wilt turned to basketball.

He showed early on his penchant for unpredictability and putting himself above the team.

- He once came out for pregame warmups wearing a scarf, a beret, and sunglasses. He shot a few layups before his 22-year-old coach, Cecil Mosenson, told him to ditch the affectations.

- Wilt obeyed but, when the game started, refused to shoot. So Mosenson benched him. "If you're not going to shoot, you're not going to play."

- A while later, with Overbrook struggling, Mosenson asked his star if he was ready to play. Despite getting no answer, the coach sent Wilt in. But he still wouldn't shoot; so out he came again.

- When the tight game entered its final minutes, Mosenson tried Chamberlain again. This time, he took over, scoring at will and leading his team to victory.

- Figuring that Wilt was testing him, Mosenson ordered him in no uncertain terms not "to pull that crap on me ever again!"

Chamberlain earned not one, not two, but three nicknames while still in high school.

- He preferred "The Big Dipper," but his family and friends called him "Dippy."

- He hated "Wilt the Stilt" but couldn't shake the odious monicker throughout his life.

- "Goliath" didn't catch on like the others.

Naturally, Overbrook produced outstanding records all three years of his high school varsity career.

- Sophomore year ('52-3): Wilt had grown two more inches to 7'1" as the Panthers won the Public League title but lost in the city championship to West Catholic despite Wilt's 29 points, which he scored against triple-teams.

- Junior year ('53-4): He scored a record 71 points in one game. This time, Overbrook won not just the public crown but the city championship as well to complete a perfect 19-0 campaign. Philadelphia Warriors owner-coach Eddie Gottlieb proclaimed Wilt the Stilt fit for pro ball already.

- Senior year ('54-5): Wilt averaged 37.4 ppg, scoring 74, 78, and 90 points in three consecutive games. As expected, the Panthers won the Public championship and got revenge against West Catholic for the city title 83-42 as Chamberlain threw in 35.

- Overbrook's final tally for his three years on the varsity: 52-3

- In his later years, Mosenson recalled Wilt with fondness: He was a freakish player. He had the rare combination of coordination, height, and skill. Plus, he had a great behavior on the court. He never went after a player or tried to show up the other team. Wilt worked hard every day; he never loafed.

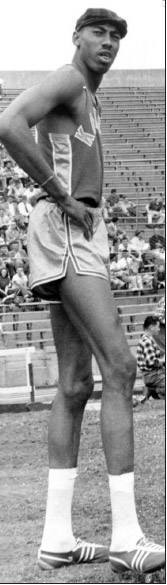

Note where Wilt wore his "knee" pads

During summer vacations, Overbrook worked at Kutsher's Hotel in the New York Catskill Mountains.

- Resorts in the area hired the country's best college basketball players to work as bellhops during the day and play in the hotels' basketball league at night. Milt Kutsher hired Red Auerbach, coach of the Boston Celtics, to coach his team. Struck by how gracefully The Stilt walked despite his size, Red was even more impressed when he saw The Dipper on the court, where he had no trouble holding his own against some of the best players in the nations.

- Red had Wilt play one-on-one against B. H. Born from Kansas, the MVP of the '53 NCAA Finals. Wilt won easily, 25-10. The defeat so dejected Born that he gave up a promising NBA career to become an engineer. If there were high school kids that good, I figured I wasn't going to make it to the pros.

- Red tried to talk Wilt into attending a New England college so the Celtics to take him as a territorial draft pick. Auerbach even asked his owner Walter Brown to offer the Chamberlain family $25,000 if their son would pick a school in the Boston area. But even though the NBA had no rule against bribing a high school player's parents, Brown considered the tactic underhanded.

- Meanwhile, Gottlieb heard about Auerbach's advances and sent his C Neil Johnston, the league's leading scorer, to tutor Wilt. Eddie didn't care where Wilt went to college because he planned to claim the young giant as the Warriors' territorial pick based on the fact that Chamberlain played high school ball in Philly.

As you can imagine, colleges created the biggest recruiting circus in NCAA history.

Continued below ...

References: The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain,

and the Golden Age of Basketball, John Taylor (2005)

Wilt, 1961: The Night of 100 Points and the Dawn of a New Era,

Gary Pomerantz (2005)

|

Wilt Chamberlain

Coach Monsenson and Chambelain

Chamberlain (dark uniform) in action

Eddie Gottlieb

Neil Johnston

|

Branch McCracken

Phog Allen

Wilt on freshman team

The Stilt with KU coed, one of many staged pictures

Dick Harp

|

Two schools pursued Wilt Chamberlain the most intensely during his senior year of high school, Kansas and Indiana.

- The recruiting battle had an extra layer of intensity because the two coaches, Branch McCracken of IU and Forrest "Phog" Allen of KU, despised each other. They refused to schedule regular season games against each other.

- One of the sources of enmity between the two was McCracken's belief that Allen "stole" Indiana high school star Clyde Lovellette from him with illegal incentives in 1948.

- McCracken thought he had the edge for Wilt because Indiana had won two national titles and boasted the first black to play basketball in the Big Ten (Bill Garrett). In fact, he was so sure Wilt was his that he announced his victory.

- But Branch underestimated his nemesis and ended up with egg on his face. Phog had had a newspaper picture of Wilt pinned to his office door since someone sent the clipping to him when The Dipper was a sophomore.

- Allen, who had learned basketball from none other than James Naismith himself when the latter coached at Kansas, also benefited from the fact that one of his players, C B. H. Born, had played in the Catskill summer league against Wilt, who scored 45 and held the older collegian to 8.

- Phog had extra motivation in his quest to sign Wilt. At age 69, he faced mandatory retirement in a year. He believed that, if he succeeded in getting Chamberlain, the university would either change the rule or make an exception for him so that he could coach Wilt when he became eligible for varsity play as a sophomore.

- The KU coach organized a campaign that produced over 500 letters from alumni and school officials begging The Dipper to enroll at their alma mater.

- Allen didn't contact the 7'2" phenom until February of his senior year. He pitched the "racially comfortable" atmosphere in Lawrence. To back up his words, he enlisted the city's prominent black citizens to woo the young giant. They told him he could single-handedly change racial attitudes in Kansas just as Jackie Robinson did in baseball. Phog successfully shielded his own checkered past, including the fact that he supported the gentlemen's agreement excluding blacks from athletics when the Big Six conference formed in 1927. Twenty years later, when the KU athletic department opened sports to blacks, Allen suggested they run track because, as he explained, that didn't require as much body contact as basketball.

- Allen visited the Chamberlains and touted the university's academic program. He even sent a chemistry professor to visit the family.

- When Wilt came to Lawrence on his recruiting visit, Phog made sure he was treated like royalty, driven to the campus in a Cadillac. The head of a Negro fraternity even loaned his girlfriend for a date. Most important of all, a group of alumni known as the "godfathers" promised Wilt $4,000 a year.

So on May 14, 1955, Chamberlain announced that he would attend Kansas on a basketball and track scholarship.

Many fine colleges and universities have shown an interest in me. But, with the help of my family and friends, I have made up my mind. I have had some professional offers too, but that can wait until I have had a college education. It has always been my ambition to study business administration and maybe some day go to law school.

- McCracken, as you might expect, didn't react gracefully. We couldn't afford that boy. He was just too rich for our blood.

- Many sportswriters assumed KU had sweetened the pot. Leonard Lewin wrote in the New York Daily Mirror: I feel sorry for the Stilt. When he enters the NBA four years from now he'll have to take a cut in salary.

- Another wrote: One pro basketball coach is said to have offered young Chamberlain 12 thousand dollars to sign a contract and pass up college ball. The question naturally pops up, "How much is Kansas U. paying Wilt to head west?" Kansas officials insist just the legal grant-in-aid prevails.

- One scribe found it ironic that Phog had campaigned for years to raise the basket in college ball. Since Chamberlain has tossed his tall hat in the Kansas ring, I have heard no further shouting by Dr. F. C. Allen for the raising of the basketball goals.

Wilt had to content himself with playing a year on the freshman squad as required by NCAA rules.

- Although Dick Harp coached the freshmen, Allen worked personally with Wilt. Among other drills, he had The Dipper shoot FTs blindfolded. (Wilt would shoot FTs throughout his NBA career as if he were blindfolded - 51%.)

- As happened a dozen years later at LSU during Pete Maravich's first year, the KU freshmen beat the varsity in the annual preseason game for the first time since the tradition began in 1923. Despite being double-teamed, Wilt scored 42.

- An unheard-of 14,000 spectators crowded the field house to get a look at the new recruit. Included were several coaches from other Big Seven schools. When Jerry Bush of Nebraska saw The Stilt make a twisting dunk behind his head, he said, I feel sick. After the game, Bush kidded Allen that he had found a weakness in Chamberlain. He doesn't handle the ball so well with his left foot.

- Convinced he would be able to coach past 70, which he reached the day of the freshman-varsity clash, Allen gushed to the press: Wilt Chamberlain's the greatest basketball player I ever saw. With him, we'll never lose a game. We could win the national championship with Wilt, two sorority girls, and two Phi Beta Kappas.

Off the court, it didn't take Wilt long to realize that the racial atmosphere in Lawrence didn't fit the rosy picture painted during his recruitment.

- His first day on campus, he was refused service at a local diner.

- He informed Allen that he would not play unless he could sleep in the same hotels and eat in the same restaurants as his teammates on road trips. Ready to do anything to please his future star, Phog immediately cancelled freshman games at Rice, SMU, LSU, and TCU.

- Chamberlain used his star status (and his unmistakeable physical presence) to do what black leaders wanted him to do - desegregate movie theaters and lunch counters. His only black teammate at KU, Maurice King, said, Nobody ever asked us to leave or refused us service. They really wanted to cater to Wilt. King related the story of a police car coming after them as they sped on the turnpike. When the officer recognized the driver, he turned off his siren and drove away.

- I single-handedly integrated Kansas, Wilt boasted throughout his life. He didn't realize that he was treated differently from all other blacks, who still faced segregation after he left KU.

- Wilt escaped the college town atmosphere by driving to Kansas City on weekends. There he found a vibrant African-American community with night clubs featuring jazz, his favorite type of music.

Wilt as a disk jockey on his own radio show, "Flip'er with Dipper," on a Topeka radio station. He denied being paid, but the athletic department, fearing NCAA investigation, ended the show after six weeks. With speculation increasing that Wilt would make an excellent addition to the U.S. team for the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, he took himself out of the running.

- The announcement sparked speculation that Chamberlain's amateur status had been compromised. A member of the Olympic Basketball Committee asked publicly: Why isn't Chamberlain a candidate for the Olympic team? Is Kansas afraid to let him get around?

- A month later, a Maryland sportswriter claimed Wilt had received money to play under an alias for a semipro team. Chamberlain vigorously denied the allegation. (Many years later, he admitted it was true.)

- If Wilt had joined the Olympic team, he would have been a teammate of his future NBA rival, Bill Russell, who won the second of two straight NCAA championships as a senior at San Francisco in Wilt's freshman year.

During the 1955-6 season, the university informed Allen that it would not waive the mandatory retirement policy for him.

- The announcement left Allen embittered and surprised Wilt, who thought "Old Phog," as he called the coach, would engineer a waiver.

- Wilt's freshman coach, Dick Harp, moved up to the varsity with him.

Continued below ...

|

The 1956-7 basketball season saw the debut of two giants: Bill Russell with the Boston Celtics and Wilt Chamberlain with the Kansas Jayhawks.

- Russell joined the Celtics in late December after playing for the U.S. Olympic team. It would take awhile to get in sync with his teammates since he missed training camp and the opening weeks of the season.

- His first game was December 22 against the St. Louis Hawks at the Boston Garden. Bill didn't start but made 3 FGs for 6 points and committed four fouls as the Celtics eked out a 95-93 victory. He missed all four FT attempts.

- Afterwards, Russ told reporters: I have to admit I was very nervous. I was very tight all the way. My shooting was way off and I was just plain lousy at the foul line. This pro game is wonderful. I learned a lot even when I was just sitting on the bench.

Another heralded rookie graced Red Auerbach's starting lineup - F Tommy Heinsohn from nearby Holy Cross.

- Heinsohn quickly developed a reputation as someone who never shot unless he had the ball. One of his teammates kept track of what Tom did when he received the ball during a game. He lost the ball once, passed it once, and shot the other 21 times.

- Tension developed between the two rookies, some of it dating back to 1955 when Holy Cross and San Francisco met in the annual Holiday Tournament in Madison Square Garden.

- Since Heinsohn played on the East Coast, he received much more media attention than Russell on the opposite coast. With extra motivation, Bill outscored Tom 24-12 and outrebounded him 22-13 as the Dons won going away 67-51.

- Heinsohn got the impression that Russell resented him. Bill valued team play and didn't appreciate a gunner like Tom. So he remained cool and distant. It didn't help that Heinsohn won the Rookie of the Year award, in part because Russell missed the first 24 games. When Commissioner Maurice Podoloff awarded the $300 check to Heinsohn, Russ told him: I think you ought to give half that check.

Why? Heinsohn asked.

Because if I had been here from the beginning of the year, you never would have gotten it. And Russell wasn't smiling.

Still, Boston compiled the best record in the eight-team league by six games.

- The Celtics were 15-6 without Russ and finished the season 44-28 in first place in the Eastern Division. They averaged 105.5 ppg, more than three ppg better than the Minneapolis Lakers.

- After the Syracuse Nationals beat the Philadelphia Warriors two straight in the best of three Eastern semifinals, the Celtics swept the Nats in three games to reach the finals against the Hawks.

The teams staged one of the greatest finals in NBA history. The series deserves more space and will be chronicled at greater length here in the future. In the meantime, here's a summary.

- Behind 37 points from their star, Bob Pettit, the Hawks upset the Celtics in Boston in Game One, 125-123 in double OT. Russell scored only 7 and fouled out.

- Facing a must-win situation in Game 2, the Celts won easily 119-99.

- The next two games were in St. Louis, where the crowd had pelted the Celtics with eggs during their regular season visits and shouted racial insults at Russell.

- The home team copped Game 3 100-98, but the Celtics, with their backs to the wall again, prevailed 123-118 to even the series again.

- Back in Boston, the Celtics breezed 124-109 but the Hawks edged them 96-94 back in St. Louis to set up the ultimate game.

- The last game was a classic that some sportswriters called one of the greatest athletic events they had ever seen. Boston won in double OT 125-123, the exact score as in double OT in Game One except reversed. So four of the seven games were decided by two points.

- Before Game 7, Russell began what became a career-long habit of throwing up before big games. He told Auerbach he was too sick to play and remained in the dressing room after the team took the court. But he quickly realized he would never forgive himself if he missed even part of the championship game and joined his teammates. He pulled down 32 rebounds before fouling out while Heinsohn tallied 37 points and 23 boards.

- In a little over a year, Bill had won an NCAA championship, Olympic title, and NBA crown.

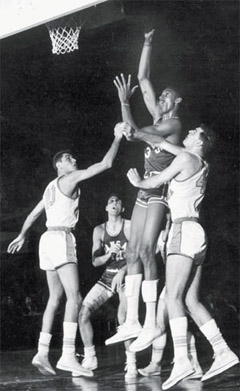

Meanwhile, Chamberlain made as big an impact on the college scene.

- Kansas began the post-Phog Allen era since the legendary 37-year coach had reached mandatory retirement age.

- Most preseason polls ranked KU #1 since ten lettermen returned in addition to the sophomore phenom, who made all the preseason All-American teams before he played even one varsity game.

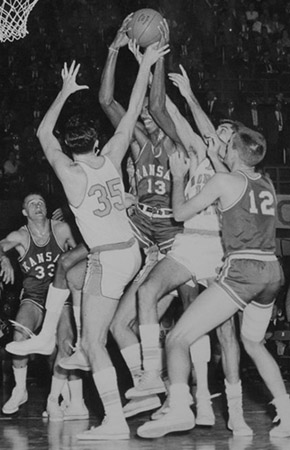

- Magazine reporters and newsreel cameras followed him from dawn to dusk the day of his first game December 3 against Northwestern. He didn't disappoint, scoring 52 points and grabbing 31 rebounds.

- As the season continued, Wilt was profiled in Time and Newsweek.

- When the Jayhawks went to the West Coast for three games during the Christmas break, 3,000 fans watched them practice in Seattle. They beat Washington twice and California once.

- After Christmas, they won the Big Seven preseason tournament, which was held before the regular season in those days. Wilt netted 93 points in three games.

- Opposing coaches already racked their brains for ways to stop him such as holding the ball on offense and collapsing two or three men on him in the post. As often happens with big men, players fouled him with abandon, leaving welts from their hacks.

Kansas continued unbeaten as the conference regular season began.

- The Hawks ran their record to 12-0 with a victory over archrival Kansas State.

- On January 14, they visited Iowa State, where Coach Bill Strannigan hatched a creative plan to stop The Dipper. He played C Don Medsker in front of Wilt. When KU lobbed the ball over him, the ISU forwards collapsed to help, conceding open shots in the corners. Chamberlain tallied only 17 points and his teammates fell into the trap, making only 13 of 46 shots. Medsker sank a 15' jump shot at the buzzer to knock the Jayhawks from the ranks of the undefeated, 39-37.

- Undaunted, Kansas beat Iowa State at home and won four more in a row before being upended at Oklahoma State 56-54. Once again, a last second basket sank the Hawks after the Aggies held the ball the last 3:47 of a tie game. A 6'8" reserve sophomore, Arlen Clark, came off the bench to hold Wilt to 8 points in the second half after he threw in three times that many in the first 20 minutes.

- By winning their final four games, KU won the Big Seven Conference to qualify for the NCAA Tournament. The ten home games drew 85,000 more than the year before. 160,000 witnessed the team's 17 road games. A writer estimated that the additional fans contributed $16,000 more in highway tolls, leading pundits to dub the new stretch of I-70 into Lawrence "the Turnpike That Wilt Built."

|

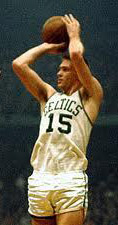

Bill Russell as a Celtic

Tom Heinsohn

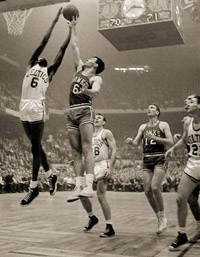

1957 Finals Action

Russell snares a rebound.

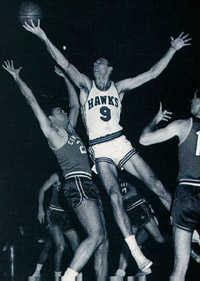

Bob Pettit in action

Cliff Hagan snares rebound.

|

|

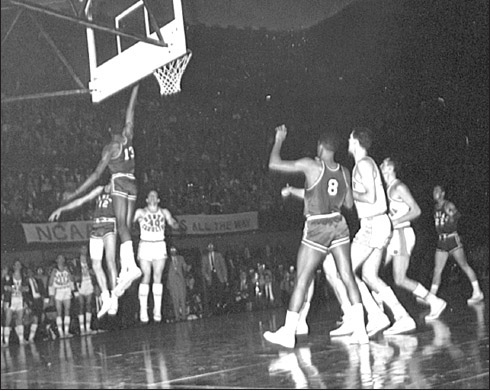

The Jayhawks traveled to Dallas for the Midwest Regional.

- Coach Dick Harp honored Allen's promise that Chamberlain would stay with the team on the road. But the only way to do that in Big D was to stay at a motel in Grandview, 26 miles away.

- During the games, older adults booed Wilt, screamed "Nigger!," threw seat cushions, pennies, and cups onto the court, and even tore the KU banners.

- Opposing players shoved and tripped Wilt and muttered the N word within earshot. To his credit, the seven-footer didn't respond to the abuse, contenting himself with winning the games, 73-65 over SMU in OT and 81-61 over Oklahoma City.

- The triumphs propelled Kansas to the Final Four at Kansas City MO, right in their backyard.

- Of all teams, they met two-time defending champion San Francisco in the semifinals. Without Russell and several other starters from the year before, the Dons were no match and fell 80-56.

That put the Jayhawks in the finals against North Carolina.

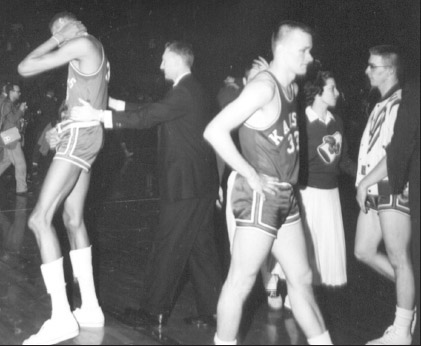

- In perhaps the greatest NCAA Final of all, the Tar Heels won in triple OT 54-53.

- Unimpressed with the other four KU starters, UNC Coach Dick McGuire decided his best chance of victory depended on denying Wilt the ball. And when he did receive, three and even four Tar Heels descended on him. As in the earlier losses, Wilt's teammates didn't hit enough open shots.

- This game would haunt Chamberlain the rest of his life. Despite the fact that he scored 23 points, nearly half his team's total, despite being double- and triple-teamed, and the fact that McGuire was right - his team was much better overall than Kansas - but won by only one point, and the fact that he was voted the MVP of the tournament, many writers would say in the years to come that the 1957 NCAA Final showed early on that Wilt couldn't win the Big One, that he choked in the clutch. He said in 1998, I got the tag of being a loser because of that game. It was the most devastating thing that ever happened to me in sports.

- Read more about the game ...

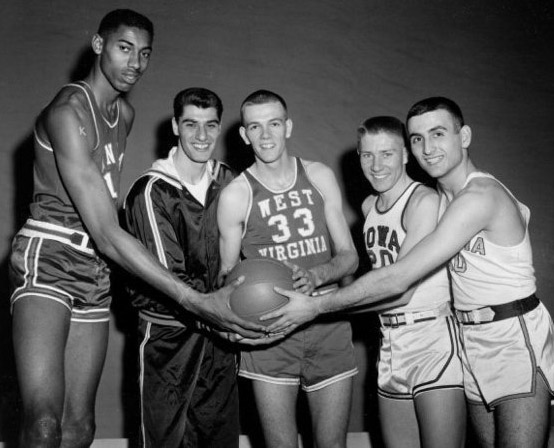

Kansas-North Carolina action in the 1957 NCAA Finals

Wilt after the Game

1957 All-America Team

L-R: Wilt Chamberlain, Kansas; Lenny Rosenbluth, UNC; Rod Hundley, West Virginia;

Gary Thompson, Iowa State; Chet Forte, Columbia

|

Dick Harp and Phog Allen

|

When North Carolina beat Kansas in triple OT for the 1957 NCAA championship, no member of the Jayhawk nation was more disappointed than Wilt Chamberlain.

- Like most Kansas fans, Wilt directed his ire mostly at Coach Dick Harp, who had the impossible task of following the legendary Phog Allen, the man who recruited Wilt.

- Allen had done Harp no favor by proclaiming before the 1956-7 season that we could win the national championship with Wilt, two sorority girls and two Phi Beta Kappas.

- Phog didn't even attend the final. The University Daily Kansan speculated: Who can say now what difference it would have made to a dog tired team to look over to the bench and see Phog sitting beside Dick Harp?

- Few realized that for a long time before Allen was forced to retire when he reached the state age limit, Harp did most of the coaching.

Even before the 1956-7 school year ended, speculation spread that Wilt would turn pro.

- The 7'2" superstar certainly contemplated the possibility. The NBA couldn't sign him until he finished his college eligibility. But the Harlem Globetrotters had no restriction. Rumors circulated that Abe Saperstein, founder and owner of the Globetrotters, had offered him $15,000-20,000.

- Wilt told reporters he had had no contact with the Globetrotters but did say this about playing basketball: It's a job. I might as well get paid.

- Others accused Wilt of being a pro as soon as he stepped on the Kansas campus because he had been paid under the table.

- The owner of the Celtics, Walter Brown, fearful that Chamberlain's arrival in the NBA could threaten the dynasty he was building around Bill Russell, asked the league to investigate whether Wilt had an illicit financial arrangment with Kansas and, if so, to ban him from the NBA.

Officials in NCAA headquarters in nearby Kansas City summoned Wilt to explain how he could afford the brand new Oldsmobile convertible he drove around campus.

- Chamberlain explained that he'd taken out a loan for the convertible and had received no illegal payments from the university or its alumni. He also denied being compensated for his campus radio show "Flipping with the Dipper."

- When the four-hour interview concluded, the chief investigator told him, It was nice talking to you, but I don't believe a word of it.

In 1960, after Wilt had left Kansas, an NCAA report concluded that benefactors had contributed $1,564 for the car (the difference between the trade-in value of the old vehicle and the cost of the new) and put the university on two-years probation.

Few were surprised at the fallout from Wilt's stay in Lawrence. The Topeka Daily Capital: Since that day in September of 1955 when a seven foot basketball player drove the second of his seven cars onto the University of Kansas campus, the Jayhawks' head has been resting squarely on the chopping block.

Twenty-five years later, Chamberlain acknowledged that three alumni "godfathers" paid him $4,000 a year in cash while he was at Kansas.

|

Chamberlain vs Oklahoma

Cheerleader Consoles Wilt

Track star

Shot-putting

Abe Saperstein and Wilt

Bob Pettit shooting FT

|

Wilt returned to Kansas for his junior year in order to win the national championship that eluded him the year before.

- But four experienced players had graduated from the '57-8 team, leaving Wilt and one other as returning lettermen.

- He spent time in New York City during the summer playing in pickup games, some of which included NBA players. He also played against Cincinnati Bearcats star Oscar Robertson in Oscar's hometown of Indianapolis.

L: Wilt surrounded by UNC players in 1957 championship game; R: Wilt vs Oklahoma

If Wilt disliked the way opponents played him the previous year, he hadn't seen anything yet.

- The Jayhawks started the season 10-0, including the championship of the preseason Big Eight tournament.

- A highlight of pre-conference play was Wilt's return to Philadelphia where a packed house at the Palestra watched Kansas defeat St. Joseph's 66-54.

- But regular season conference play, especially on the road, frustrated The Dipper. Every opponent triple-teamed him so that he could barely move. With no shot clock, some froze the ball to hold down the score and have a chance to win. An Oklahoma State defender undercut him. A Missouri Tiger bit him on the arm. Smaller defenders climbed on his back.

- The Cowboys, in their first season in the renamed Big Seven, ended Kansas's winning streak with a 52-50 victory at Lawrence. Another two-point loss, to Oklahoma in Norman, followed.

- After two victories, the Jayhawks fell again, 79-75 at home to Kansas State. During the game, Chamberlain was accidentally kneed in the groin, causing his testicles to swell. The university attributed his missing two games to "a glandular problem."

- When Nebraska, after losing 104-46 in Lawrence February 8, upset KU 43-41 in Lincoln two weeks later, the university president cancelled classes the following day.

- Kansas finished league play 8-5, not good enough for the championship and therefore not good enough to make the NCAA Tournament, which included only conference winners.

- Chamberlain averaged 30.1 ppg but only one teammate boasted a double-digit average. He again made first-team All-America.

- KU went 32-8 during his two years on the varsity, with the losses by a combined 21 points.

Wilt looked forward to the track and field season.

- He loved this purest of sports because he could compete as an individual unfettered by mediocre teammates and triple-teaming opponents.

- As a sophomore, he high-jumped 6'5" to win the conference title. He also competed in the shot put, triple jump, sprints, and the half-mile.

- The last home game of the basketball season was rescheduled for a Friday night so that Wilt could compete in the Big Seven indoor track and field championship the next day. He arrived at the meet in Kansas City, took a few practice jumps, and, wearing a warm-up jacket and a pageboy cap, high-jumped 6'6.5" to set a university record and tie for first place.

Stories circulated during the spring of 1958 that Chamberlain would forsake his final season of college eligibility.

- Despite his public denials that he had any plans to turn pro, Wilt entered into a $10,000 agreement with Look magazine that gave the magazine exclusive rights to an article announcing his plans.

- The NBA wasn't an option because league policy prohibited signing a player until four years had elapsed since his high school graduation.

- In the Look article that hit the newsstands May 23, Wilt said he was organizing two ten-man squads, one all-black, the other all-white, for a 160-game barnstorming tour that would begin in South America and continue in the U.S. through the 1958-9 basketball season. The players would include those who never got a chance to play in college or couldn't quite make the pro game.

- He also blasted college basketball, claiming that what he endured at Kansas was hurting my chances of ever developing into a successful professional player. The game I was forced to play at K.U. wasn't basketball.

- Wilt also cited his family's financial needs as another factor in his decision to play for pay as he continued to deny that he received any illegal payments from Kansas or its alumni.

The barnstorming tour turned out to be either a pipedream or a smoke screen.

- In mid-June, Chamberlain signed a one-year contract to tour with the Harlem Globetrotters for $65,000 - a colossal sum when the average NBA salary was less than $10,000. His pro debut would take place October 18 at Madison Square Garden.

- In his rambling 1992 book A View from Above, Wilt explained his fascination with the Globetrotters from an early age.

When I was a young boy first learning the game of basketball, the ultimate dream for players of color was to play with the Globetrotters. The NBA meant zero to us at that time. When you had a chance to go see the Globies play in person and be that close to them, it was like a dream come true. In my eyes ..., they were the best basketball team in the world. As I said above, men of color were not playing in the NBA at that time but the Globetrotters often played games against NBA powerhouses and all-star college teams. ... So when I was offered a chance to play for them I ... joined them. How could I not? I was so damn intrigued. Even though at the time I was considered the best player in the world, I was in awe of the Globies. The chance to play with men I dreamed about ... was more than I could refuse. The icing on the cake was all the world traveling I was going to get a chance to do. ... It was a new world opening its arms to embrace me and I've never been able to resist that.

There was one person who made an effort to derail Wilt's plans.

- Eddie Gottlieb, owner of the Philadelphia Warriors, who had reserved the "territorial rights" to draft hometown hero Chamberlain when he was still in high school, asked the NBA to allow Wilt to play with his club for the 1958-9 season.

- The other owners refused to approve the exception despite the obvious drawing power Wilt would bring for an additional year.

- However, Eddie did get the Globetrotters to schedule two appearances in Philadelphia as part of doubleheaders with Warrior games.

While all this drama played out in college basketball, Red Auerbach, Bill Russell, and the Celtics continued their winning ways until a bad break befell them.

- Boston won the Eastern Division by eight games, the same margin by which the St. Louis Hawks won the West.

- Both teams sailed through the conference semifinals and finals to meet again for the championship.

- As in '57, the Hawks stole the first game on the road 104-102. But the Celtics won the second by 24.

- The third game sealed Boston's fate. Russell leaped high to block a shot by Bob Pettit but landed heavily on his right ankle, severely spraining it.

- With Russell out, the Hawks won Game 3 but lost Game 4. Then St. Louis took the crucial Game 5 in Boston 102-100 to take a 3-2 lead.

- With his team facing elimination, Bill played in Game 6 in St. Louis with a cast on his ankle. But the night belonged to Pettit. Despite being double- and triple-teamed, he sank 50 points, including 18 of the Hawks' final 21. His tip in of a missed shot with seconds left gave St. Louis a 110-107 lead which, with no 3-point shot, allowed the Hawks to concede a meaningless basket at the buzzer.

Continued below ...

|

|

|

Red, Bill, and Wilt - VII

While Wilt Chamberlain was touring the world with the Harlem Globetrotters, Bill Russell played this third season in the NBA.

- Bill had still not developed much affection for the city of Boston or its fans (nor would he ever). He complained that he heard worse racial insults at home than \on the road.

- His rookie year, he was the only black on the team since the pioneering Celtic African-Americans from the early 1950s were no longer on the roster.

- His isolation was helped when Sam Jones joined the team for 1957-8 to be joined a year later by Bill's college teammate K. C. Jones.

- In November 1958, the Celtics flew to Charlotte NC to play the Minneapolis Lakers. Bill and the other black players had to stay at a Negro hotel. Since the game counted in the standings, Russell played but vowed he would never again play in any city where he had to sleep in a segregated hotel.

- Boston finished 52-20 in 1959 to win the division by 12 games. They had some trouble in the Eastern finals but dispatched the Syracuse Nationals in six. Then they swept the Lakers, who had finished 15 games behind St. Louis in the West but, led by sensational rookie Elgin Baylor, upset the Hawks in the playoffs.

Once his college class graduated in 1959, Chamberlain could now join the Philadelphia Warriors, who had made him a "territorial" draft choice after his last year of high school.

- Wilt made his NBA debut on October 24, 1959, at Madison Square Garden. Here's how Jeremiah Tax previewed the event in Sports Illustrated:

Framed by powerful arms that stretch 91 inches from finger tip to finger tip, one massive hand cradling the basketball as if it were a small grapefruit, the long, glistening torso giving evidence of his great total height, Wilt Chamberlain ... works out for his professional debut ... It is a sight that brings shudders to rival camps around the National Basketball Association.

The best guess is that Wilt is 7 feet 2 inches tall. It is a guess, because there has never been an official, public measurement of this giant of a man. But ... it is not Wilt's height alone that inspires fear and respect among prospective opponents. The important thing is that he is also a strong, fast, well-coordinated athlete. Consider the following: he has run the quarter mile in 49 seconds flat, bettered 6 feet 7 in the high jump, put the shot 51 feet, can lift 265 pounds in the clean-and-jerk and 210 in the military press. For none of these feats did Chamberlain prepare himself through normal training; they were casual, offhand achievements by an athlete who has always devoted his free time and effort to basketball.

- 15,000 fans watched him bucket 43 points and pull down 28 rebounds in a 118-109 victory. Philadelphia Daily News writer Jack Kiser gushed, The Age of Wilt has arrived. The NBA will never be the same again.

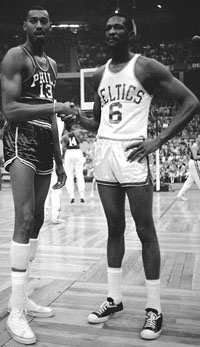

- The long-awaited Russell-Chamberlain clash took place on November 7 at the Boston Garden. Wilt scored 30 to Russell's 22, but the Celtics prevailed 113-106. Jeremiah Tax again:

What the duel proved, chiefly, is that against Russell, Chamberlain cannot get away with the few simple offensive moves he has found so effective against lesser men. Every time he tried to use his chief weapon, a fall-away jump shot, Russell went up with him; Russell's large hand flicked away at his vision, slapped at the ball, once blocked it outright - a shocking experience for Wilt Chamberlain. All told, in this man-to-man situation Chamberlain hit exactly four baskets; the rest of his 30 points were made on tip-ins and a few dunk shots ... He took 38 shots, twice as many as Russell and more than anyone else on both teams. In the second half, obviously driven to extreme measures by Russell's tenacity, he tried more hook shots than he had in all his previous games - which is just what Russell wanted him to do because the hook is a difficult and unnatural maneuver. ... But he threw it with his wrist instead of a straight arm, and from a flat-footed stance. Not one went in. On rebounds he was repeatedly kept out of position by Russell and Tom Heinsohn, and only his height and jumping ability won him 28 to Russell's 35.

- Six weeks later, Tax wrote a more positive article about the rookie:

One-third of the way through the season, it is clear that no rookie - in any sport - has ever achieved the smashing success that ... Wilt Chamberlain presently enjoys in professional basketball. From the first, he has scored more points per game and pulled down more rebounds than any other player in the league. His defensive skill, like Bill Russell's, has intimidated all rival teams, forcing them to pass up easy shots repeatedly because of a well-justified fear that Wilt might block them. Players defending against him are nearly always in danger of fouling out ... Wilt's remarkable stamina enables him to play the full 48 minutes, without substitution, whenever the Warriors need him. And he is bound to improve. As St. Louis Coach Ed Macauley says, "He will learn more from our old pros than they will from him." Finally, his presence is the principal reason why NBA attendance has increased almost 25%.

- The teams met ten times in the regular season, Boston taking six of them, four at home and two at Philly.

- With solid players around the rookie such as F Paul Arizin, F-G Tom Gola, and G Guy Rodgers, the Warriors improved from 32 wins in 1958-9 to 49 to move from 4th to 2nd place in the East behind, of course, Boston. Wilt averaged 37.6 ppg and 27.0 rpg.

Philadelphia beat Syracuse in the best two-of-three opening series to earn the right to take on the defending champion Celtics.

- With the finals alternating between the two cities starting in Boston, the home team won the first three games before the Celtics broke the string in Philly 112-104 to take a 3-1 lead.

- The Warriors got that game back in Boston 128-107 but lost 119-117 in Game Six.

- Boston then defeated the Hawks in seven games for their third title in the last four years.

The pattern had been set for the remaining nine years that Bill and Wilt played against each other.

- Wilt compiled the gaudier statistics.

- With Auerbach building the best team every year and outcoaching opponents until his retirement in 1966, the Celtics won eight straight titles (including the one in '59 before Wilt joined the NBA).

- In '67, Bill's first as player-coach, Wilt got his championship with the Philadelphia 76ers, who replaced the Warriors when they moved to San Francisco where Wilt played three seasons before returning to his hometown for the '64-5 campaign.

- Russell summoned one last, great effort in 1968 to defeat the Los Angeles Lakers of Wilt, Jerry West, and Elgin Baylor in the finals.

- After the Celts finished 4th in the East the next year, Bill retired and turned the reins over to Havlicek.

- Chamberlain got a second crown in '72 when the Lakers put together an incredible 69-13 season and beat the Knicks in the finals.

- Wilt played one more year in LA, losing to the Knicks in the finals this time, before retiring.

Some final stats: In their head-to-head matchups:

- Wilt averaged 28.7 points and 28.7 rebounds;

- Bill averaged 14.5 points and 23.7 rebounds;

- Russell's teams won 84, Wilt's won 58.

In his 1966 autobiography, Russell said this about his rival.

When I play Chamberlain, I play a team. Wilt, conversely, plays his game and the other fall into his wake and are swept along. ... Chamberlain came into the league in 1959-60 and from that moment Russell had a big challenge on his hands. The theory was that Chamberlain was going to ruin my style of defense. Few realized that we play an entirely different kind of game. Chamberlain's concept of the game is basically offensive ... Chamberlain came into the league and was supposed to put me into total eclipse. I think he has had the opposite effect. In a sense, he has magnified my importance to the team.

We have always been friends, except on a basketball court. ... I owe a debt of gratitude to Chamberlain. He made me a $100,001 a year ballplayer. ... [After the 1965 season, the Celtics] offered, through [GM] Auerbach, $75,000. I said I was going to consider retiring. They stuck at $75,000. ... Philadelphia announced that Wilt Chamberlain had signed a contract for three years at $100,000 per year. Good for Wilt Chamberlain. And good for Bill Russell. I just smiled and laughed and was happy as hell. If Chamberlain was worth $100,000, then I figured on the basis of all those championships I was worth just $1 a year more.

|

Chamberlain-Russell before

their first meeting.

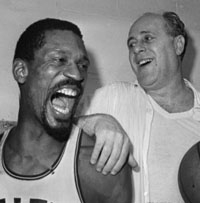

Russell and Auerbach exult after another victory.

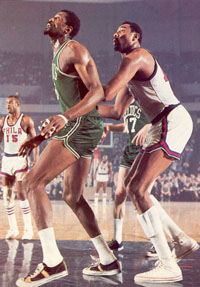

Russell-Chamberlain in a later year

Chamberlain and Russell at odds

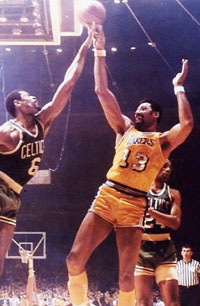

Celtics-Lakers Big Man clash

|

References: The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball, John Taylor (2005)

The Book of Basketball, Bill Simmons (2009); Go Up for Glory, Bill Russell (1966)

|

|