CONTENTS

The Spaceman

Exhibition Games

Everyday Babe

The End at Ebbets Field and Polo Grounds

Babe's Final Turn on the Mound

Did He or Didn't He?

A. "SPLIT" CENTURY

Rickey Being Rickey

Meteoric Rise and Fall of Karl Spooner

Baseball

Vignettes Index

Baseball

Magazine

Golden Rankings Home

|

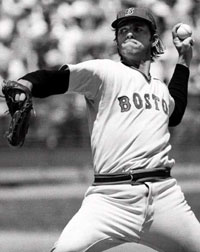

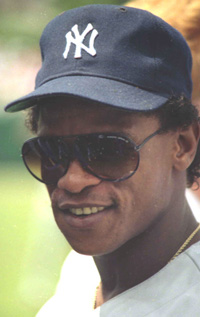

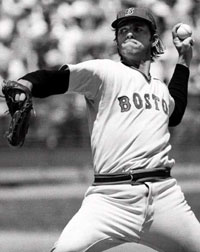

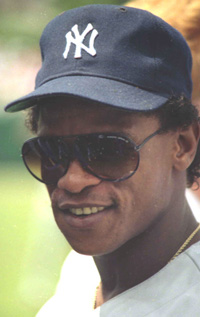

"Spaceman" Bill Lee

"Spaceman" Bill Lee |

LHP Bill Lee was known as " the Spaceman" in his ML career (1969-1982). It is not hard to find incidents that justify the monicker. His flakiness appeared during his college days at USC when that program topped the nation under Rod Dedeaux. (Did you know Dedeaux was born in New Orleans?)

- The 6'3" Lee fancied himself a hitter as well as a pitcher. So one season he refused to attend preseason practice unless the coach promised him a chance to play 1B. When Rod agreed to let Spaceman take some batting practice, he ended his college holdout and returned to the team and pitched.

- One day, Bill showed up late for a doubleheader. Reason? The early morning dew on the ground, together with the acorns in the OF, produced an unpleasant odor.

- Once in the middle of a game, Lee called the coach, catcher, and infield to the mound to inform them that his lips were chapped.

- He cruised Sunset Strip on Halloween in drag. On a road trip, he slid down an airport baggage chute wearing the red wig the team awarded to the club clown.

- Dedeaux had played two games for Casey Stengel's Brooklyn Dodgers in 1935. "I always understood everything Casey said, which sometimes worried me," said Rod. "But I know that all my hours with Casey helped prepare me for Bill Lee." – at least as well as any coach could be prepared for the Spaceman.

- Bill played four years for the Trojans and obtained a degree in geography. The chairman of that department said Bill "was as good a student as we ever had around here. I'd rank him among the brightest 5% to 10%."

- On the mound, he developed dozens of slow, spinning deliveries to go with a serviceable fastball. As a result, he compiled a 38-8 record at USC, including two victories in the 1968 College World Series, which the Trojans won. As a consequence, Lee was drafted by the Red Sox in the first round.

|

Lee joined the Red Sox during the 1969 season to replace injured star P Jim Lonborg. Ironically, he was assigned #37, which had been Casey Stengel's number with the Yankees as well as Jimmy Piersall's with Boston. ( Read about Piersall's antics.) To say that the staid Red Sox, "possibly the most straitlaced organization in all of pro sports," weren't ready for him is an understatement.

Lee got into frequent hot water with the front office and even the league with his outrageous statements.

- He was an outspoken advocate for the decriminalization of marijuana and openly defied the pot laws.

- He once described George Steinbrenner as "a convicted felon." (George made illegal contributions to Richard Nixon's campaign.)

- During a spitball controversy, he said that AL President Joe Cronin acted "like an idiot."

- During the 1975 World Series between the Red Sox and the Reds, Lee reacted adversely to manager Darrell Johnson's decision to pitch Luis Tiant in Game Six instead of Bill. The decision was "stupid. But Darrell's been falling out of trees and landing on his feet all season." Lee did start Game 7 and pitched creditably, leaving with a lead in the seventh.

- In 1978, he called manager Don Zimmer "a gerbil."

The Red Sox longed to trade Lee even though he ran off three 17-victory seasons in a row (1973-5) but didn't want to face the wrath of the fans, who loved him. They could, however, trade his closest friends on the team, who had organized themselves as the Royal Order of the Buffalo Heads, and did so until only OF Bernie Carbo remained. When Bernie was traded to Cleveland, Lee wept for 20 minutes, ripped his home telephone off the wall, and vowed he'd never play for Boston again. He called Zimmer "a no-good front-running son of a bitch" and labeled the co-owners of the team as "gutless." The next day, he jogged three miles to Fenway Park and returned to the team. When he was fined $533, he told the front office to make it $1,500 so he could take several more days off. (They didn't.)

|

Bill Lee |

In addition to running his mouth, Bill outraged the baseball Establishment with his antics, such as:

- Wearing onto the field at various times a gas mask, a Daniel Boone cap, and a beanie with a propeller.

- Arriving at the ball park in a black outfit that he described as Mexican funeral wear in honor of his rumored release from the team.

- Getting into heated arguments on the mound with C Pudge Fisk in the middle of games.

- Jumping off motel balconies into swimming pools.

- Playing Frisbee games with bleacherites while in the bullpen.

- Provoking teammate Reggie Smith until Reggie beat him up.

- Getting assaulted during Winter ball in Puerto Rico by C Ellie Rodriguez and his cousin in retaliation for Lee's one-punch KO of Ellie in an earlier fracas.

- Hurting his left arm badly in a melee in Yankee Stadium which Lee didn't start but which provided several Yankees with excuses to punish him physically for his past comments about them.

Lee was finally traded to the Montreal Expos before the 1979 season.

Reference: "In an Orbit All His Own," Curry Kirkpatrick, Sports Illustrated, August 7, 1978

Exhibition games have long been a part of every ML team's season. In the days before television beamed games all over the nation, exhibition contests drew well and provided extra income for both the big league club and the minor league host.

- All teams "barnstormed" their way from their spring training site in the South to the site of their first regular season game. In 1923, for example, the Yankees broke training camp in New Orleans in late March and joined the Brooklyn Dodgers coming from Clearwater FL for a series of games in Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri. The big attraction, of course, was Babe Ruth, who is credited with hitting the longest HR ever in dozens of cities and towns.

- Intra-city rivals often played a series of games either before or even after the regular season (assuming neither made the World Series). The Chicago City Series was a big draw almost every year early in the 20th century, attracting even more local interest that the World Series. The Phillies and A's often played a series the weekend before the regular season began. Starting in 1910, the Yankees and Giants played in an informal "City Series." In the '40s and '50s, the Yankees alternated playing the Giants and Dodgers in the annual Mayor's Trophy game. In 1963, following the two NL teams' departure to the West Coast five years earlier, the annual game was resumed with the expansion Mets providing the opposition.

- Clubs regularly scheduled exhibition games on travel days during the regular season. With no players' union to protest, teams expected all players, and especially the stars, to make at least a token appearance in the games. The Yankees, in particular, liked to show off the greatest player of the age, Babe Ruth, whenever possible. In 1923, for example, the club scheduled 14 unofficial games on travel days during the regular season. To show further how important the games were, consider what the Yankees did on July 24, 1924, in the thick of a pennant race with the Washington Senators. Trailing the Tigers by one run going into the ninth inning at Yankee Stadium, New York stopped the contest, thus accepting defeat, so that the team could make a 6 o'clock train for an exhibition game the next day in Indianapolis on their way to Chicago.

|

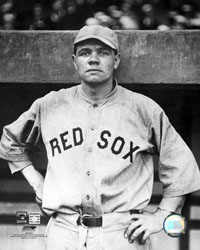

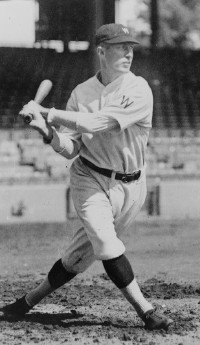

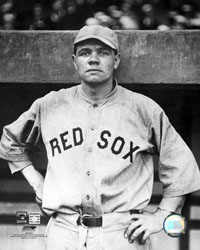

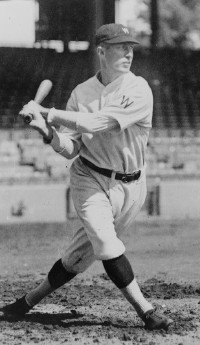

Babe Ruth

Top of Page |

On May 6, 1918, Babe Ruth played a position other than P for the first time in a major league game. Fans had been after manager Ed Barrow to do this for several years.

- For the 1917 season, Babe compiled a 24-13 record on the mound with a 2.01 ERA in 326 innings. At the plate, he hit .325 with a .472 slugging percentage. The league averages in those two categories were .248 and .320. He also socked the two longest HRs recorded that season.

- Adding to the impetus to play Ruth daily was the fact that the Red Sox, like all teams, were losing players to the World War. In addition to those drafted into the military, others took jobs with "war-related industries" to avoid front line duty.

Babe started the May 6 game against the Yankees at 1B and celebrated with, what else, a HR. Moving on to Washington, he played first in the opening two games of the series. In the first game, he hit a HR off the great Walter Johnson that was the first hit by anyone that season in spacious Griffith Stadium. For this effort, Ruth won a suit from a local tailor. Two days later, he faced Johnson on the mound but lost 4-3 in ten innings. However, he went 5-for-5 with three doubles and a triple that traveled 430 ft to CF.

When the Red Sox returned to Fenway Park, Ruth started in LF against the St. Louis Browns. Still raw at both 1B and the OF, he ended up in the box seats on May 16 after running hard for a foul ball.

During the month of June, Babe pitched and played 1B, LF, and CF. He enjoyed hitting every day so much that he told manager Barrow that he didn't want to pitch any more. This started a year and a half of contentious relations that led to Ruth being sold to the Yankees after the 1919 season.

|

Reference: The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs, Bill Jenkinson

|

The End at Ebbets Fields and Polo Grounds

The glorious last game in Yankee Stadium in September 2008 called to mind decidedly different scenarios 51 years earlier when the Brooklyn Dodgers played their last game at Ebbets Field and the New York Giants bid farewell to the Polo Grounds before both franchises moved to the West Coast.

|

|

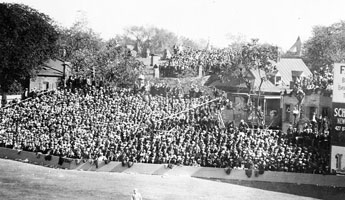

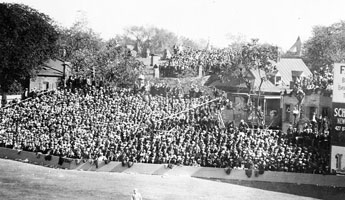

Ebbets Field

Picture of first game at Ebbets Field

|

- Sunday, September 29, 1957: A slightly larger crowd of 11,606 witnessed the last contest at the Polo Grounds against those same Pirates. Bob Friend pitched the visitors to a 9-1 victory. The 6th-place Giants finished last in the league in attendance, attracting only 653,923. New York skipper Bill Rigney started this alignment.

- Danny O'Connell 2B

- Don Mueller RF

- Willie Mays CF

- Dusty Rhodes LF

- Bobby Thomson 3B

- Whitey Lockman 1B

- Daryl Spencer SS

- Wes Westrum C

- Johnny Antonelli P

|

Polo Grounds

Top of Page |

|

Babe's Final Turn on the Mound

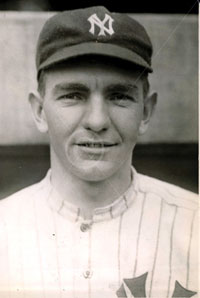

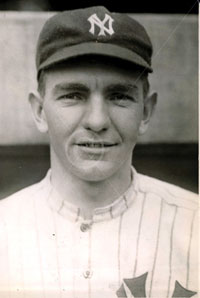

Bob Shawkey

Babe Ruth

|

Near the end of the 1930 season, Babe Ruth approached the Yankees' rookie manager, Bob Shawkey, about pitching the last game of the season in Boston. Babe figured it would help draw a crowd for an otherwise meaningless game. The third place Yanks had no chance of catching the Philadelphia A's, who were in the process of winning the second of what would be three straight pennants. The last series was so insignificant that Shawkey excused C Bill Dickey and this three top starters, Red Ruffing, George Pipgras, and Herb Pennock, from even traveling to Beantown. Considering that Babe would be pitching with nine years' rest, Shawkey readily agreed.

So Babe toed the rubber on September 28 against the last place Red Sox before a disappointing crowd of 12,000. The day before, in the second game of the series, The Sultan of Swat hit two homers for a league-leading 49 for the season. In the finale, he hurled a complete game 9-3 victory for Boston's 102nd defeat. He scattered 11 hits and struck out 3. Babe also started two DPs on hot smashes back to the box. Hitting in his usual #3 spot in the batting order, Ruth contributed two singles. Lou Gehrig, who always hit #4, volunteered to take Babe's spot in LF where he made two putouts. At the plate, Larrupin' Lou's 3-for-5 raised his final average to .379, just behind Al Simmons' .381 for the AL batting crown.

Three years later, in his 20th year in the AL, Ruth reprised his 1930 performance. He again volunteered to pitch the final game, this one also against Boston but at Yankee Stadium. At age 39 and not in the best of condition, Babe prepared for his start by tossing batting practice for several weeks. Once again, New York was not in pennant contention. To attract more fans, the Yankees also added a pregame fungo-hitting contest, which Ruth won with a 395-foot drive. Then he entertained the crowd of 25,000 by completing a 6-5 victory. After shutting out the 7th-place Red Sox for the first five innings, Babe labored through the remaining four frames. Yankees' trainer Doc Painter rubbed Ruth's aching arm between innings. The Bambino gutted out a 6-5 victory, the winning blow being his own 34th HR in the 6th. Afterwards, a spent Ruth announced that he was done as a pitcher. |

Bill Dickey

Lou Gehrig

Top of Page |

Reference: "The Babe Called His Shot – Not From the Batter's Box, From the Pitcher's Mound,"

Ken Schlager, The New York Times, August 17, 2008

|

1925 World Series Game 3. The Washington Senators lead the Pittsburgh Pirates 4-3 in the top of the eighth with two out and none on. The teams are tied at one game apiece.

Pirates C Earl Smith hits a fly toward the temporary bleachers in right-center field at Griffith Stadium. RF Sam Rice races to the wall, leaps, and spears the ball backhanded before disappearing into the crowd. After about 15 seconds, Rice emerges and shows the ball in his glove to the umpire. A newspaper reporter called it "one of the most remarkable catches ever seen in a World Series game." The Pirates argue that the play should be ruled a HR because Rice didn't immediately return the ball to the infield and therefore could have lost the ball in the crowd and then gotten it back.

However, the umpires reject the argument. The Senators hold on to win. However, Pittsburgh wins the series in seven.

|

Sam Rice |

Temporary World Series Bleachers (L) at Griffith Stadium (R)

When accosted by reporters about the alleged catch after Game 3, Rice played coy, simply saying the umpires ruled that he caught the ball. For the rest of his life, he refused to say whether the umps were correct. Instead, he left a sealed letter with the Hall of Fame which was to be opened after his death.

Edgar Charles "Sam" Rice had an interesting, though tragic, background. Born in 1890 in Indiana, he chose to work on his father's farm. Married at 19, he saw his life wrecked by a 1912 tornado that killed his parents, wife, and two daughters. Understandably, he chose not to remain on the farm and joined the Navy. While stationed in Mexico, he picked up baseball, using his speed to beat out hits and chase down fly balls. Clark Griffith, owner of the Senators, signed him as a pitcher in 1915. As a 25-year-old 5'9" 150 lb rookie, he quickly moved to the OF to take advantage of his speed. Rice played with the Senators through their last pennant-winning season in 1933 before finishing his career with one year in Cleveland. The lifetime .322 hitter and all-time hits leader in Senators history, Rice was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1963. He is one of the few players to amass more hits after the age 40 than he did before age 30.

Back to the letter. When Sam died in 1974, his letter was opened: "At no time did I lose possession of the ball."

|

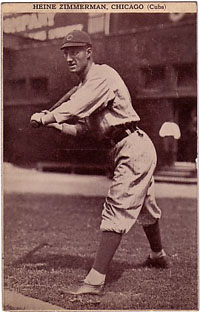

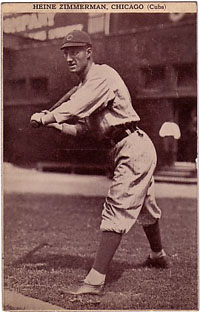

Coming off the finest of his six seasons with the Chicago Cubs, Henry "Heinie" Zimmerman looked forward to the 1913 campaign. The previous year he hit .372 with 99 RBI and 14 HR while playing an outstanding hot corner. However, 1913 brought Heinie the wrong kind of publicity thanks to his constant run-ins with umpires.

- May 19: Umpire Charles "Cy" Rigler ejected Zimmerman in the fourth inning at Philadelphia.

- June 6: William Byron gave Heinie the thumb in the fourth inning as the Cubs hosted the Boston Braves.

- Heinie outdid himself later in the month, being tossed from three home games at the West Side Grounds in a five-day period. (Wrigley Field opened that season as Weeghman Park but was used by the Chicago Whales of the new Federal League.)

- June 13: After what many thought was an obvious forceout of the Brooklyn Superbas' Jake Daubert at 3B, Malcolm Eason called "safe." According to the Chicago Tribune, "Heinie roared, being ordered out of the game quick as one could wink."

- June 15: Attempting to slide into home in the 7th inning against the Superbas, Zimmerman was called out, whereupon he cursed ump William Brennan who promptly tossed him.

- June 17: While on 3B in the third inning against the Philadelphia Phillies, Heinie was given the heave-ho by plate umpire Bill Klem for hollering at him when he called Roger Bresnahan out on strikes.

- The following letter appeared in the Chicago Tribune of June 19, 1913

I'm Irish and I haven't much use for the Dutch, but there's one Dutchman I think a whole lot of and that's Heinie Zimmerman. I think so much of him that I love to see him fight the other fellows. And, ah, there's the rub. Darn him, he doesn't play regular. He gets canned too often for fighting the umps. It ain't fair for those who pay their money to see Zim swat the pill and it also ain't fair to the rest of the bunch.

Now to come down to brass tacks: Here's a $100 bill split in two. Go give half to Heine and if he stays in the game for two weeks – that is, if he doesn't get canned by an ump in that time, pass him the other half and a piece of sticking plaster to stick 'em together.

Seriously, I want Zim to quit kicking. Two weeks of living with umps will do everybody a lot of good, Zim most of all. Please put a mask on my name, and sign: A. "SPLIT" CENTURY

- The Tribune gave half to Zim and the other half to Bill Klem. Upon hearing the stipulations, Heinie boasted, "Say, just hand me that one-half and watch me get the other. I'm through fussing with umpires anyway. It don't get you anything. I don't intend to be put out of the game again this year. From now on you'll see me as a model guy on the ball field. That $100 is just as good as mine."

- The next day, Ring Lardner, a Tribune sportswriter, asked: "Suppose Zim is canned before the expiration of two weeks. Will Mr. Century get his half back?" That day, Heinie was fined $200 – not for arguing with the umps but rather with his manager, Johnny Evers. Referring to the Cubs' previous manager, Evers said: "If he had said to [Frank] Chance what he said to me, he would not play all season long." Clearly Zimmerman had anger management issues, to use the modern phrase.

- Gamblers laid 3-2 odds that Zim would win the C-note. One fan gave Heinie half of a dollar bill under the same conditions as Split A. Century,

- Heinie almost lost the bet June 24 when he began to argue with umpire Hank O'Day but, remembering the half-a-hundred he kept in his back pocket, caught himself and avoided ejection.

- When the Cubs arrived in Cincinnati for a series with the Reds on June 25, Zim's former teammate Joe Tinker demanded to see the bill to make sure it wasn't a hoax. Tinker, still thinking the "bet" was a joke, tore Heinie's part of the bill in half. The Tribune reported, "Now instead of one-half he has two quarters of a yellowback."

- July 2: Heinie had only to last one more game at home against the Pittsburgh Pirates to win the $100. That afternoon fans held their breath as Zim began yelling at Ernest Quigley after the ump called him out on an attempted steal of home. Once again, he stopped short and completed the two weeks without ejection. (The umps, knowing of the wager, may have been more patient with him than they might have otherwise, not wanting to be the one to raise the ire of the fans. But that is speculation long after the fact.)

- Klem gave Heinie the other half of the "Split Century," and the fan turned over the other half of the dollar bill. So Zim won $101 for his good conduct.

|

Bill Klem

Johnny Evers

Hank O'Day

Joe Tinker

Top of Page |

Reference: "The 'Split Century,'" Arthur H. Ahrens, Baseball Research Journal 1973

|

|

Rickey Henderson was voted into the Hall of Fame on the basis of these incredible stats.

- Most stolen bases in history (1,406)

- Most runs scored (2,295)

- #2 in walks (2,190) – he was ahead when he retired but now trails Barry Bonds (2,558)

- 1990 AL MVP

- 10-time All-Star

Sporting News interviewed former teammates and opponents of the all-time steals leader. Some excerpts.

- "I never liked him as an opponent, but once we were teammates, he was awesome." Tom Candiotti

- "He was his own topic. I remember one day he was taking a picture with Spuds MacKenzie the dog – and I just cracked up. The writers asked what was funny. I told them if they started interviewing them both, they would get better comments out of Spuds." Ron Kittle

- "I asked him why he doesn't swing at bad pitches. He said, 'Rickey don't swing at balls.'" Rex Hudler

- "He hated playing day games. He led off the game with a K, and as he walked through the dugut, he was telling some guy to 'get out of Rickey's body.'" Tom Candiotti

- "When Rickey would milk a walk, steal second, then steal third, all eyes were on him. Eyes in the stands, on the field, and in the dugout." Bob Lacey

- "Rickey was on his own team, and we played alongside him. He should have won the MVP award about five times in his career. He only played when he wanted to. Such a talent." Ron Kittle

- "There's the story of the million-dollar check from Oakland. The team called him and said, 'Rickey, you have not cashed that check yet.' He'd framed it.'" Dave Beard

- Question to catchers: When Henderson was on first, did it change the way you called a game?

"Not much. He was so fast, you couldn't throw him out anyway, so we tried to get the hitter out." Marv Foley

"You called more fastballs. He was a guy who could change a game because speed never goes in a slump." Tim Laudner

Top of Page

|

|

|

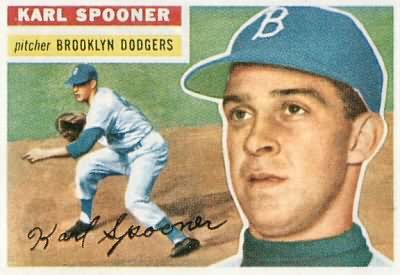

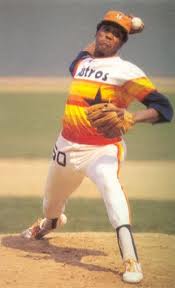

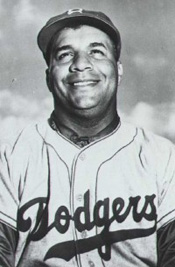

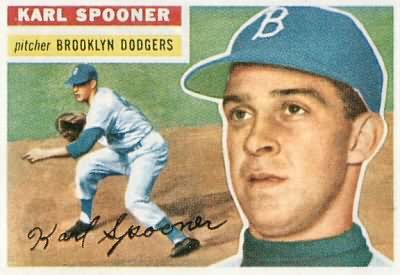

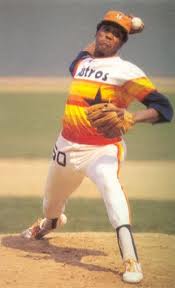

Meteoric Rise and Fall of Karl Spooner

Karl Spooner

J. R. Richard

Roy Campanella

Top of Page |

23-year-old Karl Spooner made a dazzling ML debut on September 22, 1954 for the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field against the league-leading New York Giants.

- Spooner, a 6'3" 195 lb southpaw, struck out 15 Giants, a record for pitchers making their major league debut.

- J. R. Richard tied Spooner for the Houston Astros on September 5, 1971, against the San Francisco Giants.

- Spooner gave up only three hits in the 3-0 victory. He walked three.

- With the Giants having clinched the pennant since they were 7.5 games ahead of the second place Dodgers with only four to play, only 3,256 saw Spooner's gem.

- Spooner doubled off opposing left Johnny Antonelli in his first MLB at-bat.

Four days later, on the last day of the season, Spooner tossed another shutout.

- The last-place Pittsburgh Pirates were the victims, 1-0, at Ebbets Field.

- This time Spooner fanned "only" 12 while walking three again. He limited the Bucs to four hits, two of them by LF Dick Hall, who later became a full-time P.

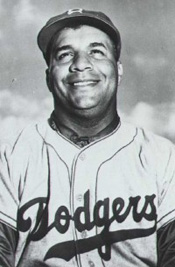

- Spooner's 27 Ks remains the most by a P in his first two ML contests. C Roy Campanella later called him "the greatest young P I've ever seen."

- Dodger fans rhymed, "Spooner should have come up sooner."

It would be nice to report that Spooner went on to a long, productive career. Alas, that is not the case.

- Karl had suffered a knee injury in June, 1954, while playing pepper. When he returned two weeks later, he pitched without a windup and with a shorter stride. This cured the control problems that had caused him to walk 112 batters to that point. With his new motion, he won 21 games and set a record with 262 Ks to earn the callup by the parent club.

- In the off-season, he had his right knee operated on. At spring training 1955, Spooner said that his repaired knee didn't bother him, despite his increased weight of 192 pounds. However, he hurt his arm during spring training, supposedly because he entered a game without warming up properly.

- Despite his sore wing, he spent the entire 1955 season with Brooklyn. He went 8-6 with a 3.65 ERA in 29 games, 14 of which were starts.

- On August 29, he pitched a gem, beating the Cardinals, 6-1. He allowed only six hits while striking out nine and walking one. In his next start, Spooner shut out the Pirates but struck out only three.

- Karl appeared in two games in the '55 World Series against the Yankees.

- He pitched three scoreless innings in relief in Game 2 at Yankee Stadium, a 4-1 Brooklyn defeat.

- He started Game 6, also at Yankee Stadium, but lasted only 1/3 of an inning, allowed three hits, two walks, and five runs. The Yankees won 5-1 to set up the famous Game 7, in which Johnny Podres shutout the Bronx Bombers to give Brooklyn its only World Series Championship.

When he reported to spring training in 1956, Spooner complained of a sore arm.

- The Dodgers optioned him to the minors and over the next few years he descended as low as class D.

- He never pitched another inning in the big leagues and retired after the 1958 season.

Karl Spooner died in 1984 at age 52 in upstate New York where he grew up.

|

|

|